Published online Apr 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4462

Revised: January 7, 2014

Accepted: February 17, 2014

Published online: April 21, 2014

A rare case of a severely constipated patient with rectal aganglionosis is herein reported. The patient, who had no megacolon/megarectum, underwent a STARR, i.e., stapled transanal rectal resection, for obstructed defecation, but her symptoms were not relieved. She started suffering from severe chronic proctalgia possibly due to peri-retained staples fibrosis. Intestinal transit times were normal and no megarectum/megacolon was found at barium enema. A diverting sigmoidostomy was then carried out, which was complicated by an early parastomal hernia, which affected stoma emptying. She also had a severe diverting proctitis, causing rectal bleeding, and still complained of both proctalgia and tenesmus. A deep rectal biopsy under anesthesia showed no ganglia in the rectum, whereas ganglia were present and normal in the sigmoid at the stoma site. As she refused a Duhamel procedure, an intersphincteric rectal resection and a refashioning of the stoma was scheduled. This case report shows that a complete assessment of the potential causes of constipation should be carried out prior to any surgical procedure.

Core tip: A patient with persisting constipation following STARR or transanal stapled rectal resection, carried out for rectal internal prolapse, needed a diverting sigmoidostomy. She also had proctalgia due to retained staples. Despite normal manometry and intestinal transit times, a deep rectal biopsy showed marked alterations of the intrinsic plexus, which was the main cause of symptoms. Both morphology and function of the anorectum should be carefully investigated prior to indicate surgery. Obstructed defecation may be considered an “Iceberg syndrome”: the rectal internal prolapse is just the tip of the iceberg, and occult underlying lesions should be properly diagnosed and cured.

- Citation: Pescatori LC, Villanacci V, Pescatori M. Failed stapled rectal resection in a constipated patient with rectal aganglionosis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(15): 4462-4466

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i15/4462.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4462

Chronic constipation may present in form of reduced frequency or evacuation or as obstructed defecation, which is usually characterized by frequent attempts to evacuate with a lot of straining and without the sensation to have the rectum emptied. It may also require self-digitation and it is frequently associated with a rectal internal mucosal prolapse. Constipation may also be present since the childhood and may be due to a defect of rectal ganglia and to an uneffective peristalsis, usually showed by abnormal anorectal manometry and intestinal transit time[1]. To find both conditions causing constipation in the same patient is rather unusual. Even more unusual, the first time to our knowledge, is that, despite normal manometry and transit times, the patient had a rectal aganglionosis. Therefore we thought it was worth publishing this rare case.

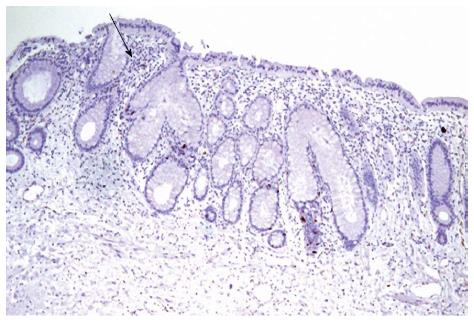

A 56 years-old nulliparous female patient presented at our Unit complaining of severe proctalgia, tenesmus and rectal bleeding two years after a STARR procedure for obstructed defecation and six months after a diverting sigmoidostomy. She also had a parastomal hernia. The patient looked anxious, but was in good general conditions. Routine blood tests, EKG and Chest X-ray were normal. The study of large bowel transit, carried out eight months before by means of radiopaque markers was also normal, as 80% of the markers had been expelled within 72 h. Nevertheless she complained of constipation, i.e., infrequent and difficult emptying of the stoma. At the digital exploration a tender painful mass was felt at the level of the lower rectum, just above the anal canal, on both the posterior and the anterior aspects, in correspondence of retained staples, two of which could be detected by palpation. Proctoscopy showed a marked inflamed rectum, with bleeding ulcerations and a hyperemic fragile mucosa. As the patient reported that her constipation started in the childhood an adult hypoganglionosis was suspected and a deep rectal biopsy under anesthesia was carried out, despite the anorectal manometry, performed one year before, had shown a normal recto-anal inhibitory reflex. A deep colonic biopsy at the site of the sigmoidostomy was also carried out, as shown in Figure 1.

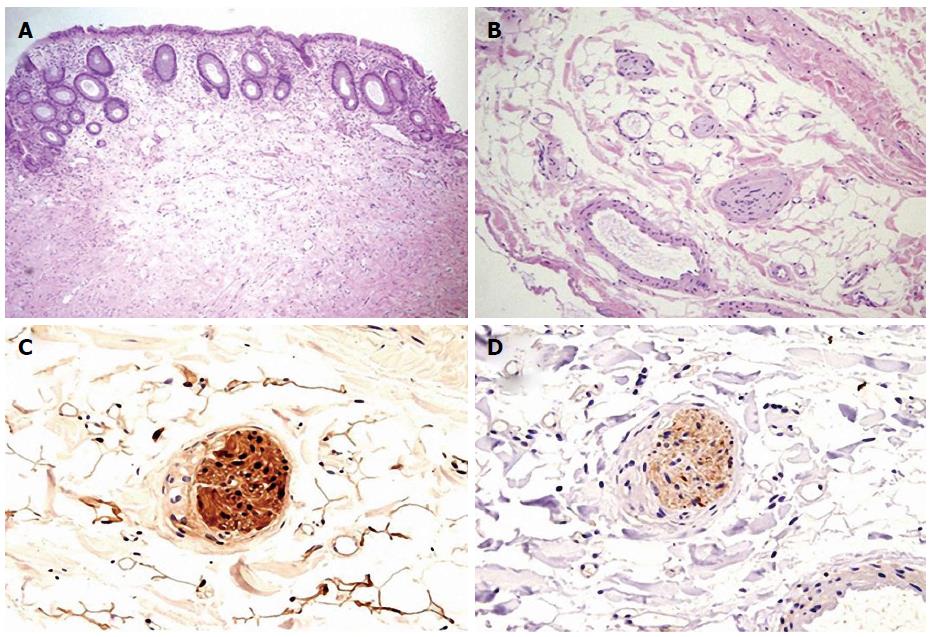

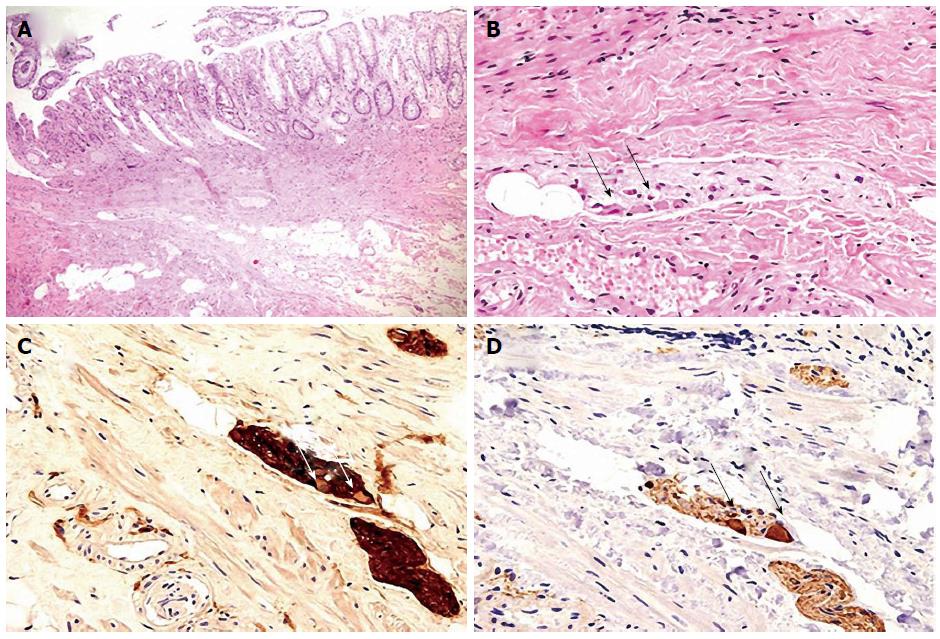

The G.I. pathologist (V.V.) diagnosed a diversion proctitis and a marked rectal alteration of the ganglion cells, whereas the intrinsic innervations at the deep colonic biopsy looked normal (Figures 2-4).

As the patient’s symptoms were worsening, a surgical operation was advised consisting of rectosigmoid resection and Duhamel anastomosis at the anal canal. The patient, once informed that this major operation had to be scheduled in two stages (recto-sigmoid resection and diverting ileostomy, plus closure of the stoma after six months), refused to undergo a restorative procedure as was afraid to become incontinent. An intersphincteric resection of the rectum and the lower sigmoid with a refashioning of the stoma, i.e., correction of the parastomal hernia with a mesh and fashioning of a terminal sigmoidostomy was then scheduled.

Constipation may be due to several causes, among them rectal aganglionosis, which may also occur in the adult. In this case a complete absence of the ganglia is unlikely, whereas either an hypoganglionosis or a ganglion dysplasia is much more frequent[2]. However, patients with rectal aganglionosis, or Hirschprung’s disease, usually have a megarectum-megacolon, an absence or alteration of the recto-anal inhibitory reflex at anorectal manometry and slowered intestinal transit times[3], whereas recto-anal reflex and transit time were normal in our patient. Moreover, patients with rectal a- or hypoganglionosis and those with neuronal dysplasia are likely to have a slow transit constipation with an empty rectum and a reduced frequency of the evacuations, whereas our patient more often suffered from obstructed defecation, i.e., various ineffective attempts to empty the bowel, requiring straining and sometime self-digitation, accompanied by pelvi-perineal heaviness and sense of incomplete evacuation.

Due to these symptoms, she underwent her first operation, i.e., a STARR procedure, which is a double stapled resection of the anterior and posterior wall of the lower rectum, aimed at correcting the recto-rectal or recto-anal intussusception. Boccasanta et al[4] achieved good results on the short-term, but also reported 20% of painful defecation and proctalgia in 20% of their patient at one year, which was the symptom reported by our patient. Moreover, pain may arise at the site of staple line due to the peristaple fibrosis, triggering the nervous network on the puborectalis muscle[5], exactly the same area where our patient felt the maximum pain at the digital exploration. Recurrence of symptoms, i.e., constipation, following STARR is widely reported by the literature: according Gagliardi et al[6] 55% of the patients still are constipated 18 mo after surgery. This was the case of our patient.

Symptoms are likely to have persisted because a complete assessment for the potential causes for constipation was not carried pre-operatively. According to our theory of obstructed defecation as an “iceberg syndrome”, based on a prospective study carried out on 100 patients, the recto-anal intussusception is just “the tip of the iceberg” and a number of potential both functional and organic “underwater rocks”, i.e., underlying occult lesions, should be investigated prior to indicate surgery, e.g., altered psychological pattern[7]. Should we have seen the patients first, we would have performed a deep rectal biopsy, which would have revealed the disordered ganglia, and a psychological assessment, which would have probably shown a high level of anxiety. Then, in case of unsuccessful biofeed-back, colonic irrigation and psychological support, we would have carried first a non-invasive Lynn rectal myectomy, a procedure often effective in case of short rectal aganglionosis and then, in case of failure, a Duhamel procedure.

Due to both proctalgia and recurrent severe constipation after STARR, she underwent a stoma creation in another hospital. Stoma creation is an alternative treatment to restorative surgeries for persisting constipation not responding to conservative and other surgical treatment[8]. Finally, parastomal hernia is the most frequent complication after stoma formation[9].

Diversion proctitis, which affected our patient, may arise after fecal diversion due to the alteration of the trophism of the rectal mucosa, which is due to the passage of the stool[10]. Bleeding is one of the more common symptoms in patient s with diverting proctitis.

The fact that our patient refused a major restorative operation is comprehensible, as Duhamel procedure may be followed by fecal incontinence in a number of cases[11]. Therefore an intersphincteric resection of the rectum and the lower sigmoid, which may be carried out by a combined transanal and abdominal route with a cosmetic Pfannestiel incision seemed to us a valid alternative. The excision of the peristapled fibrosis, aimed at curing the proctalgia, was also planned.

In conclusion, this clinical case seemed to us worth to be reported as it seems quite unusual, due to the absence of rectal ganglia in an adult with normal anorectal manometry and intestinal transit time study. This discrepancy might be due to the fact that the pathological disorders of the intrinsic nerves was not severe enough to completely impair large bowel motility. Moreover, the present report may offer a warning against the abuse of a novel high-cost procedure, such as the STARR operation, which may carry high recurrence ad reintervention rate, without a proper complete assessment of the patient prior to surgery.

The patient suffered from anxiety, persisting constipation, i.e., difficulties to empty her stoma, and severe proctalgia following STARR and sigmoidostomy.

This study suspected that constipation was also due to other reasons rather than simply the rectal internal mucosal prolapse causing obstructed defecation, for which the STARR had been carried out, and we wanted to investigate if the patient had a pathology of the ganglia in the intrinsic plexus, as she started to suffer constipation from her infancy.

Blood test were normal and anorectal manometry, carried out elsewhere, was normal.

Intestinal transit times, also performed elsewhere after the ingestion of 20 radiopaque markers, were normals.

The deep rectal biopsy showed diversion proctitis and absence of ganglion cells, whereas the intrinsic nervous system was normal at the deep sigmoid biopsy and the biopsies taken close to the STARR staple line showed a fibrosis triggering the nerve spindles above the puborectalis muscle.

This study suggested an intersphincteric resection of the rectum plus agrapphectomy, as the patient had refused a Duhamel procedure for fear of incontinence, and steroid enemas which improved the diversion proctitis.

The patient also had a parastomal hernia causing troubled stool evacuation through the stoma, and her anxiety, which might have worsened constipation prior to the STARR, was mainly due to the loss of an adoptive son.

STARR is a transanal stapled resection of the rectum, aimed at excising rectocele and rectal internal prolapse, which carries 20% of chronic proctalgia and occasional life-threatening complications.

This case report demonstrates that normal anorectal manometry and intestinal transit time cannot exclude rectal aganglionosis, rectal biopsy being the gold-standard for the diagnosis, and supports our theory of constipation as an “Iceberg syndrome”, in which lesions such rectal internal mucosal prolapse, often targeted by the surgeons, are just “the tip of the iceberg”, the main causes of symptoms being underlying occult lesions, such as, in this case, rectal aganglionosis and, possibly, anxiety.

They could not explain with sound data the discordance between rectal aganglionosis and normal manometry and transit times study, this is perhaps the weakness of the study.

P- Reviewers: Furnari M, Hassan M S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Camilleri M, Szarka L. Dysmotility of the small intestine and colon. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 5th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell 2009; 1108-1156. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Pescatori M, Mattana C, Castiglioni GC. Adult megacolon due to total hypoganglionosis. Br J Surg. 1986;73:765. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Morais MB, Sdepanian VL, Tahan S, Goshima S, Soares AC, Motta ME, Fagundes Neto U. [Effectiveness of anorectal manometry using the balloon method to identify the inhibitory recto-anal reflex for diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease]. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2005;51:313-317; discussion 312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Boccasanta P, Venturi M, Stuto A, Bottini C, Caviglia A, Carriero A, Mascagni D, Mauri R, Sofo L, Landolfi V. Stapled transanal rectal resection for outlet obstruction: a prospective, multicenter trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1285-1296; discussion 1285-1296. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 222] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | De Nardi P, Bottini C, Faticanti Scucchi L, Palazzi A, Pescatori M. Proctalgia in a patient with staples retained in the puborectalis muscle after STARR operation. Tech Coloproctol. 2007;11:353-356. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Gagliardi G, Pescatori M, Altomare DF, Binda GA, Bottini C, Dodi G, Filingeri V, Milito G, Rinaldi M, Romano G. Results, outcome predictors, and complications after stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:186-195; discussion 195. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 142] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pescatori M, Spyrou M, Pulvirenti d’Urso A. A prospective evaluation of occult disorders in obstructed defecation using the ‘iceberg diagram’. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:785-789. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 69] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pfeifer J. Surgery for constipation. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2006;53:71-79. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hansson BM. Parastomal hernia: treatment and prevention 2013; where do we go from here? Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1467-1470. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Winslet MC, Poxon V, Youngs DJ, Thompson H, Keighley MR. A pathophysiologic study of diversion proctitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177:57-61. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Keshtgar AS, Ward HC, Clayden GS, de Sousa NM. Investigations for incontinence and constipation after surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003;19:4-8. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |