Published online Dec 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i48.9198

Revised: October 26, 2013

Accepted: November 12, 2013

Published online: December 28, 2013

Currently, alcoholic cirrhosis is the second leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States and Europe. The quality of life and survival after a liver transplantation (LT) in patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD) are similar to those in patients with other cirrhosis etiologies. The alcoholic relapse rate after a LT varies from 10%-50%, and these relapse patients are the ones who present a reduced long-term survival, mainly due to cardiovascular diseases and the onset of de novo neoplasms, including lung and upper aerodigestive tract. Nearly 40% of ALD recipients resume smoking and resume it early post-LT. Therefore, our pre-and post-LT follow-up efforts regarding ALD should be focused not only on alcoholic relapse but also on treating and avoiding other modifiable risk factors such as tobacco. The psychiatric and psychosocial pre-LT evaluation and the post-LT follow-up with physicians, psychiatrists and addiction specialists are important for reversing these problems because these professionals help to identify patients at risk for relapse as well as those patients who have relapsed, thus enabling responsive actions.

Core tip: Transplanted alcoholic liver disease (ALD) patients who relapse have an increased long-term mortality due to cardiovascular pathologies and the onset of de novo neoplasms, including lung and upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Nearly 40% of ALD recipients resume smoking and resume it early post-liver transplantation (LT). Therefore, our pre-and post-LT follow-up efforts regarding alcoholic liver disease should be focused not only on alcoholic relapse but also on treating and avoiding other modifiable risk factors such as tobacco. The psychiatric and psychosocial pre-LT evaluation and the post-LT follow-up with physicians, psychiatrists and addiction specialists are important for reversing these problems.

- Citation: Iruzubieta P, Crespo J, Fábrega E. Long-term survival after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(48): 9198-9208

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i48/9198.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i48.9198

Excessive alcohol consumption causes approximately 2.5 million deaths per year and is responsible for almost 4% of mortality worldwide. Alcohol has been associated with nearly 60 types of diseases and is the third leading risk factor for disease and disability worldwide. Furthermore, excessive alcohol consumption contributes to multiple social problems, including violence, child neglect and absenteeism[1].

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is the main cause of cirrhosis in Western countries and contributes to one third of the mortality associated with liver cirrhosis. Furthermore, ALD is the second most common indication for liver transplantation (LT) in the United States and Western Europe[2-7], accounting for about 40% of transplants in Europe and 20% of transplants in the United States[2-7].

If we analyze the medium- and long-term survival of a transplant patient, there is no doubt that the recipients with an alcoholic etiology have great results, with a European global 5-year survival rate of 73% and a 10-year survival rate of 59%[2,3], rates that are superior to those for recipients with other etiologies (Table 1)[3]. Therefore, we can infer that ALD is a good indication for LT[7]. However, these excellent results are diminished when a harmful alcohol consumption relapse occurs. These relapses and their possible consequences on the transplant and on the survival and quality of life of the patient, as well as possible actions to avoid relapses, are discussed below.

| Indication for LT | Patients (n) | From 1988 to 2009 | ||

| 1 yr | 5 yr | 10 yr | ||

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 15019 | 86% | 73% | 59% |

| Acute hepatic failure | 6507 | 70% | 64% | 58% |

| Cirrhosis virus C | 10753 | 80% | 65% | 53% |

| Cirrhosis viral C and alcoholic | 1790 | 85% | 69% | 54% |

| Cirrhosis virus B | 4187 | 83% | 74% | 68% |

| Hepatocarcinoma and cirrhosis | 9122 | 83% | 62% | 49% |

| Cholestatic disease | 9114 | 87% | 78% | 70% |

| Autoimmune cirrhosis | 1892 | 85% | 76% | 67% |

| Hemochromatosis | 468 | 76% | 66% | 53% |

An evidence-based approach was used for this review. MEDLINE search was performed to September 2013 using the following MeSH terms: liver transplantation, alcohol-related disorders, alcohol-induced disorders, drug abuse, substance abuse, tobacco, and neoplasm. Searches were limited to English language articles. References of suitable articles were searched for other appropriate articles.

Quality of life involves physical, mental and social well-being, including working life, and is considered a survival indicator that even surpasses traditional indicators[8]. In the cirrhotic patient, a decrease in physical, psychological and intellectual capabilities occurs alongside liver function impairment[9]. Therefore, it is logical to believe that those patients with advanced liver disease might have a significant reduction in their quality of life. Therefore, the question we might ask is the following: does LT improve the quality of life in these patients? To answer this question, numerous studies that evaluated the quality of life after LT have been performed[10-17]. However, it is not easy to extrapolate the results of these studies due to the heterogeneity of the post-transplantation follow-up times and the instruments that were used to evaluate the different spheres comprising the quality of life[10-17]. In general, studies reveal a significant short-term improvement in the quality of life with no differences observed between ALD and non-alcoholic liver disease[10-18]. Notably, although ALD patients seem less likely to be involved in structured social activities during the post-LT phase than the patients who were transplanted as a result of other etiologies, the ALD patients return to society to lead active and productive lives[19]. Few studies analyzed the quality of life long-term. As a representative study, the study by Ruppert et al[17]. that included a 12-year follow-up after LT does not show a progressive loss of quality of life in these patients after the first year of LT[17].

Regarding job reinsertion, the age at the time of the LT, the duration of the pre-transplant disability and the physical and general health status of the patient are the factors that correlate more with employment[14,20-22]. Globally, approximately half of the LT patients return to work[20-22], with no differences between the ALD patients and those with the remaining etiologies[15,23].

We must recall that, although LT effectively restores the physiological function of the liver and reverses the complications of portal hypertension, LT does not treat the underlying alcoholism. Alcoholism is a life-long disease that is often characterized by episodes of a relapsing-remitting pattern of alcohol use despite the physical, psychological and social consequences, wherein the probability of long-term sobriety becomes robust only after 5 years of sustained abstinence[24-26].

Addiction specialists define relapse as the prolonged resumption of heavy alcohol intake and distinguish this harmful drinking behavior from so-called slips, which are defined as sporadic drinking episodes followed by the reestablishment of abstinence[27]. This definition of alcoholic relapse is in contrast to that by most transplant centers that consider any alcohol consumption after LT to be unacceptable and define recidivism as any use of alcohol after LT[28]. Most of these episodes of alcohol abuse are effectively diagnosed with interviews and validated self-reporting questionnaires[29,30].

Reviews summarizing the post-transplantation alcoholic relapse rates note differences across studies ranging from 10%-95%, likely due to several factors, including variations in the study methodology, the definition and assessment of relapse and the duration of the follow-up (Table 2)[28,31-60]. In general, the risk that alcoholic recipients return to any alcohol use after LT is between 10%-50% with 8-year follow-ups[28,31-60]. More specifically, between 20 and 50% of the patients who received a liver transplant for end-stage ALD acknowledge some alcohol use in the first 5 years after LT, and 10%-15% will resume heavy drinking[28,55,59]. This finding compares favorably to post-treatment relapse rates as high as 80%-95% in treatment studies of alcoholics without ALD[24].

| Ref. | Study design | Patients (n) | Year | Follow-up median or mean (mo) | Relapse rate |

| Bird [34] | Retrospective | 18 | 1990 | 84 | 17% |

| Kumar et al[48] | Retrospective | 52 | 1990 | 25 | 12% |

| Gish et al[42] | Prospective | 29 | 1993 | 24 | 24% |

| Knechtle et al[38] | Retrospective | 32 | 1993 | Not stated | 13% |

| Berlakovich et al[22] | Retrospective | 44 | 1994 | 78 | 32% |

| Howard et al[45] | Retrospective | 20 | 1994 | 43 | 95% |

| Krom et al[48] | Retrospective | 30 | 1994 | Not stated | 13% |

| Osorio et al[51] | Retrospective | 43 | 1994 | 21 | 19% |

| Gerhardt et al[41] | Retrospective | 41 | 1996 | 47 | 49% |

| Tringali et al[56] | Retrospective | 58 | 1996 | 27 | 21% |

| Zibari et al[58] | Retrospective | 29 | 1996 | Not stated | 7% |

| Coffman et al[84] | Prospective | 91 | 1997 | Not stated | 20% |

| Anand et al[31] | Retrospective | 39 | 1997 | 25 | 13% |

| Everson et al[38] | Retrospective | 42 | 1997 | Not stated | 17% |

| Foster et al[40] | Retrospective | 63 | 1997 | 49 | 21% |

| Lucey et al[50] | Retrospective | 50 | 1997 | 63 | 34% |

| Stefanini et al[53] | Retrospective | 18 | 1997 | Not stated | 27% |

| Fabrega et al[39] | Prospective | 44 | 1998 | 40 | 18% |

| Tang et al[54] | Retrospective | 56 | 1998 | 24 | 50% |

| Yates et al[57] | Retrospective | 43 | 1998 | 21 | 19% |

| Gledhill et al[44] | Retrospective | 24 | 1999 | 14 | 25% |

| Pageaux et al[75] | Retrospective | 53 | 1999 | 32 | 42% |

| Pereira et al[13] | Retrospective | 56 | 2000 | 30 | 50% |

| Burra et al[73] | Prospective | 34 | 2000 | 40 | 33% |

| Jain et al[79] | Retrospective | 185 | 2000 | 94 | 20% |

| Dimartini et al[37] | Prospective | 36 | 2001 | 12 | 38% |

| Gish et al[43] | Prospective | 61 | 2001 | 83 | 20% |

| Mackie et al[28] | Retrospective | 46 | 2001 | 25 | 53% |

| Bellamy et al[32] | Retrospective | 123 | 2001 | 84 | 13% |

| Karman et al[57] | Retrospective | 49 | 2001 | 36 | 21% |

| Bravata et al[93] | Retrospective | 313 | 2001 | Not stated | 32% |

| Pageaux et al[52] | Retrospective | 128 | 2003 | 54 | 31% |

| Jauhar et al[86] | Retrospective | 111 | 2004 | 44 | 15% |

| Cuadrado et al[36] | Retrospective | 54 | 2005 | 99 | 26% |

| Bjornsson et al[35] | Retrospective | 103 | 2005 | 31 | 33% |

| Kelly et al[85] | Retrospective | 90 | 2006 | 67 | 31% |

| Pfitzman et al[83] | Retrospective | 300 | 2007 | 89 | 19% |

| Karim et al[91] | Retrospective | 80 | 2010 | Not stated | 10% |

| Schmeding et al[60] | Retrospective | 300 | 2011 | 84 | 27% |

| Rice et al[74] | Retrospective | 300 | 2013 | 78 | 16% |

In a meta-analysis performed in 2008 on the risk of recurrence of substance use after solid organ transplantation that included 54 studies, 50 of which were on LT, it was concluded that the relapse rate of alcohol consumption after LT was 5.6 cases per 100 patients/year, and the relapse rate of excessive consumption was 2.5 cases per 100 patients/year[27]. Additionally, the authors concluded that it was possible that these cumulative incidence rates would become stable at some point that could not be established because few of the studies had a post-transplant follow-up over 7-8 years[27].

Being able to determine the threshold of initiation of alcohol consumption after a liver transplant would be of great clinical and therapeutic utility because this knowledge would allow us to plan specific interventions more accurately. DiMartini et al[61] have described four different patterns of alcohol consumption depending on the starting date, quantity and duration as follows: (1) Minimum consumption over a long period; (2) Early consumption that progresses rapidly to moderate consumption; (3) Early consumption that progresses continuously to a harmful consumption; and (4) Moderate consumption with a late start. These results indicate that we should maintain surveillance after the first year post-LT, despite the fact that the rates for the initiation of consumption generally attenuate over time post-transplantation, probably due to the increase in the stability of sobriety over time[30].

The impact of alcohol use on the patient is not entirely clear. The available literature suggests that abusive drinking leads to a decrease in both graft and patient survival and may also lead to the lack of therapeutic compliance.

Adherence to immunosuppressant medication: In LT, adherence to the immunosuppressant treatment and any other drugs medically prescribed is crucial for positive short- and long-term results in the transplanted patients because non-adherence to these measures might lead to graft rejection and failure[62]. Reviews summarizing the nonadherence rates post-transplantation note differences across studies ranging from 3%-47%, probably due to several factors, including variations in study methodology, definitions and the small number of patients included in the studies[63-65].

Therefore, we question whether the consumption or abuse of substances pre-LT increases the risk of non-adherence to immunosuppressant treatment[63,66] and whether an alcoholic relapse is associated with pre-LT alcohol use[36,62,63]. Berlakovich et al[63] studied the effect of alcohol consumption on adherence and found that the patients who relapsed (15 of the 118 transplanted ALD patients) had a non-adherence rate that was no different from that of the patients who did not relapse. This finding was also demonstrated in a study performed in our hospital, where there was no association between the adherence to drug treatment and the presence or absence of alcoholic relapse in a series of transplanted ALD patients[36]. We believe that this concept is endorsed by the meta-analysis of Dew et al[27], which showed a lack of association. Specifically, these authors observed that European studies presented a lower non-adherence rate to immunosuppressant treatment compared to the North American studies, despite presenting significantly higher relapse rates of harmful alcohol consumption[27].

Thus, the lack of adherence seems to be linked to the personality of the patient, the acknowledgement of their disease, the complexity of the medical prescriptions, the presence of family support and the doctor-patient relationship, more so more than to alcohol consumption[67,68].

Liver graft: Resuming alcohol consumption after LT may damage the graft because of poor compliance with immunosuppressive drug treatment and alcohol-related liver injury. Graft loss from recurrent disease related to alcohol use is rare[69,70]. Globally, graft dysfunction related to relapse ranges from 0%-17%, although deaths related to relapse range from 0%-5%[52,71]. There are few studies on the severity of the liver lesions associated with alcohol consumption after LT on ALD patients[60,72-74]. Rice et al[74] found that alcohol relapse is associated with advanced fibrosis on biopsy. In contrast, our histologic study revealed only mild hepatic changes directly attributable to alcohol[36]. As reported by Pageaux et al[52,75], fatty changes and pericellular fibrosis represented the most relevant histological findings in patients who resumed heavy alcohol intake.

In contrast, several studies have shown that ALD LT patients have a lower rejection risk compared to other LT indications, suggesting an inhibitory effect of alcohol over some components of the immune response[2,76-78]. We have corroborated this finding and observed a lower incidence of acute rejection among patients who relapse to alcohol consumption compared to abstemious patients[36].

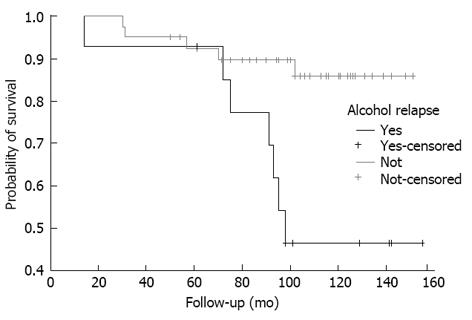

Long-term survival: Jain et al[79] observed that the 5-year post-transplantation survival rate was significantly lower for transplanted ALD patients compared to transplanted non-alcoholic liver disease patients, mainly due to cardiovascular events and de novo neoplasms, especially of the aerodigestive tract, which suggests that immunosuppression by itself is not an initiation factor for malignant changes[80,81]. We reached a similar conclusion after we evaluated the alcoholic relapse risk in a series of transplanted ALD patients and the influence of a relapse on survival[35]. In our case, the 5-year survival rate was similar between relapsers and non-relapsers (92.9% vs 92.4%, respectively), but after 10 years, the survival rate decreased significantly in the relapse patients (45.1% vs 85.5%), with malignant tumors and cardiovascular events the main cause of death in these patients (Figure 1)[36]. In addition, tobacco consumption was observed in all the patients with an alcoholic relapse and in only one quarter of the abstemious patients, which might explain the higher mortality rate due to cardiovascular events and neoplasms in these patients; this finding has been observed in other studies, as will be discussed later. However, the transplanted ALD patients are potentially affected not only by alcohol consumption but also by liver diseases with other etiologies. This finding has been shown in a recent study in which excessive alcohol consumption had a negative impact on long-term survival after LT regardless of the indication[82].

Despite these results, it is important to distinguish from among the relapsers those who are “slip” drinkers (mild alcohol consumption that is usually isolated or self-limited) and those who are “heavy” drinkers (a long period of alcohol consumption with a loss of control) because the former have a better survival rate compared to the latter[83].

Because of the above findings, it is important to identify relapse patients, but it is more important to prevent this relapse by identifying the patients at risk.

In order to predict the post-LT alcoholic relapse risk with a high degree of accuracy, it is necessary to acknowledge the risk factors that have a strong correlation, which has not yet been achieved. In this regard, numerous studies have identified factors related to the risk of post-LT alcoholic relapse, such as alcohol dependence, an age less than 40 years at the time of the transplantation, a lack of family and social support, a family history of alcoholism, personality or psychiatric disorders, previous abstinence or substance abuse failures, younger age at LT, and the refusal of further rehabilitation before the LT[30,37,40,42,43,58,78,83-87]. However, this association has not yet been corroborated in other studies[26,30,37,54,75,84-86]. For this reason, Kotlyar et al[88] decided to perform a critical review of the literature on LT in ALD candidates and concluded that patients with a lack of social support, active smoking, psychotic or personality disorders or a pattern of nonadherence should be listed only with reservation, and those who have a diagnosis of alcohol abuse as opposed to alcohol dependence may make better transplant candidates. Finally, the most controversial among these risk factors is the 6-mo pre-LT period of abstinence, about which many studies have reported a high predictive power regarding relapse[27,30,34,89-91], while others have not found such a correlation[40,79,85,86,88,92].

Most LT centers in Europe and the United States require a minimum of 6 mo of abstinence before being included in the waiting list. This common practice is based on two points: first, the possibility of improving liver function and possibly avoiding the LT, and second, the higher alcoholic relapse rate reported in patients with a period of abstinence less than 6 mo[51,93]. Both points have been discussed. Veldt et al[94] demonstrated that those with irreversible ALD were identified with 3 mo of abstinence; out of 74 patients with a Child-Pugh C liver function, the percentage of patients with improvement after 1, 2 and 3 mo of abstinence was 23%, 40% and 66%, respectively, and the remaining 33% did not show improvement at a 1-year follow-up. Furthermore, it has not been proven that this 6-mo abstinence period improves survival after LT[95]. Considering all of this, and although improved post-LT abstinence rates have been documented with a longer pre-LT abstinence period, a cut-off point has not yet been established[30,40]. Therefore, the pre-LT alcohol abstinence period could be shortened for some patients because this factor by itself is a poor indicator of post-LT relapse. In addition, some patients, especially those with a high Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score, have a considerable risk of mortality during the 6 mo abstinence period[96,97].

In conclusion, a thorough assessment by a trained alcoholism and addiction professional, rather that defined sobriety periods, should be the tool used to assess the future risk of alcoholic relapse in the alcoholic patient.

Patients who undergo LT have an unexpectedly high rate of de novo extrahepatic cancer[98,99], including lung and upper aerodigestive tract cancer[98,100,101], and studies have reported that patients with ALD are particularly affected[79,99,102]. Indeed, these tumors are known to be associated with alcohol intake and smoking because the carcinogenic or co-carcinogenic effects of smoking and drinking might be enhanced by the post-LT immunosuppressive therapy[103]. The purported mechanisms of alcohol-mediated oncogenesis are poorly understood, but these pathways may involve the carcinogenic properties of acetaldehyde and/or the inhibition of DNA methylation via the alteration of retinoid processing[104,105]. Saigal et al[106] found that patients who underwent LT for ALD appeared to have an increased risk of developing post-transplantation malignancies compared with those who underwent LT for other liver diseases. These authors hypothesized that a tumorigenic action mediated by the immunosuppressive effect of alcohol on natural killer cells could explain this observation. In fact, in the non-immunosuppressed population, alcoholism is associated with an increased risk for several malignancies, including liver and alimentary tract tumors[107,108]. Jain et al[79] observed a higher rate of de novo oropharyngeal and pulmonary neoplasms in transplanted ALD patients than in those with a non-alcoholic disease, similar to Duvoux et al[102], suggesting the presence of other initiators of malignant changes in addition to immunosuppression. Among the identified risk factors, alcohol and tobacco consumption were highlighted[98,99,109], data also obtained in our study[36].

Regarding tobacco, nearly 90% of alcoholics smoke[110], compared to 26.7% of the general population of the United States[111]. Regarding the candidates for LT, approximately 60% are smokers[112,113] and 15%-40% continue to smoke after the LT[112,114]. DiMartini et al[114] found that nearly 40% of ALD recipients resume smoking and resume it early post-LT, increase their consumption over time and quickly become tobacco dependent. In a recent meta-analysis, active smoking was revealed as one of the major risk cofactors, independent of alcoholic relapse, of long-term morbidity and mortality in transplant recipients, either from cardiovascular complications or from de novo neoplasms[88]. This data was confirmed in numerous studies[36,109,114-121]. In an interesting study from a conceptual point of view, Herrero et al[122] showed that smoking withdrawal after LT may have a protective effect against the development of neoplasia. In particular, these researchers observed that patients with a smoking history who continued smoking after the LT, presented a hazard ratio of approximately 20 for the development of neoplasms associated with tobacco (head and neck, lung, esophagus, kidney and urinary tract carcinomas), while the risk of developing these neoplasms was reduced significantly in ex-smokers[122]. Furthermore, as noted earlier, smoking is also a risk for cardiovascular disease, and this is one of the most frequent causes of late mortality after LT[36,123]. Pungpapong et al[113] found a higher rate of vascular complications in LT recipients who had a history of smoking. Those who quit smoking 2 years prior to the transplantation reduced the incidence of vascular complications by 58%. Therefore, our pre- and post-LT follow-up efforts regarding ALD should be focused not only on alcoholic relapse but also on treating and avoiding other modifiable risk factors such as tobacco, not simply because of what was discussed earlier, but because we now acknowledge that tobacco is a risk factor for alcohol abuse. In a recent study on mice, it was observed that the rodents exposed to nicotine tended to ingest alcohol more frequently than those that were not administered such a substance due to a reduction in the dopamine response of the reward-response system in the brain, which thus decreased the pleasurable response to alcohol[124]. Given all the above-mentioned observations, the establishment of control programs and post-LT interventions could perhaps reduce the mortality in these patients, as will be discussed below.

Several approaches have been evaluated to reduce alcohol recidivism in alcoholic patients after LT, but there is no standardized approach, and the available data are few and often controversial. In some liver transplant centers, alcoholic patients are encouraged to attend support groups, even if the data demonstrating the efficacy of such treatment in this cluster of patients are currently lacking. In a pilot study, Georgiou et al[125] reported that psychological interventions could be a valid approach to enhance motivation in these patients. However, this study was conducted on a limited number of patients, and the efficacy of this intervention on alcohol recidivism after LT was not evaluated. Björnsson et al[35] evaluated the impact of the management of alcoholic patients by addiction psychiatrists, social workers and tutors in the period before LT and reported a 22% prevalence of alcohol recidivism in the treated group vs 48% in the untreated group. The presence of an alcohol addiction unit within a liver transplant center is not usual, but the study of Addolorato et al[126] suggests that it could represent a useful approach to reducing alcohol recidivism after LT. However, objective and accurate indicators of abstinence are required[127]. Direct detection in the blood or breath only assesses alcohol intake within the preceding 10-12 h[39,128]. Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) is an indirect marker that reflects alcohol intake in the previous 1-4 wk[129,130]; however, the daily consumption of 60-89 g of ethanol for a period of at least 7-10 d is required for a positive result. Therefore, CDT is inappropriate for the detection of low-to-moderate alcohol intake. Furthermore, wide ranges in sensitivity and specificity of 46%-73% and 70%-100%, respectively, have been reported[131]. Nevertheless, a high rate of false-positives with the CDT test has been reported, particularly in patients with severe liver damage[131].

Currently, the determination of ethyl glucuronide (EtG), a metabolic product of alcohol, either in the urine or in the hair of patients offers a new, reliable possibility for the detection of alcohol intake[132-135]. Urinary EtG (uEtG) remains positive for up to 80 h after alcohol consumption and allows for the detection of very small amounts of ethanol (uptake of < 5 g)[133,135] with a sensitivity and specificity of 89% and 99%, respectively[131]. However, positive uEtG tests may occur after the accidental consumption of foods containing alcohol, such as chocolate, cake and others. To reduce this problem in the transplant setting, a higher cut-off level for uEtG than what is routinely used (> 0.5 mg/L instead of > 0.1 mg/L) is recommended[132].

Furthermore, the detection of EtG in the scalp hair of patients is a powerful tool for monitoring abstinence over a retrospective period of up to 6 mo. Each hair segment of 1 cm in length reflects alcohol consumption over a period of approximately 1 mo. The test has been validated for a maximal hair length of 6 cm[135].

Thus, based on the above, we can infer that regular monitoring after LT is critical for determining the ongoing abstinence from tobacco and alcohol and for providing treatment assistance when tobacco or alcohol use are identified. Using a combination of methods (patient interviews by a trained alcoholism and addiction professional connected to the transplant team, independent caregiver reports and biochemical monitoring) provides the greatest yield because every method can add to the number of identified cases[27].

As we have discussed previously, patients who undergo LT have an unexpectedly high rate of de novo extrahepatic cancer[98,99], including lung and upper aerodigestive tract cancer[100,102], and studies have reported that patients with ALD are particularly affected[79,99,102]. Therefore, apart from identifying and acting on predisposing factors for the development of neoplasms (such as tobacco use, solar exposure and infections from oncogenic viruses), intensive tumor screening protocols have been suggested for these patients. Herrero et al[109] concluded that ALD transplant patients, smokers or ex-smokers, should have a further follow-up, including a low-radiation-dose thorax computed tomography (CT) scan, a consultation with an ear, nose and throat specialist and a urine exam, as suggested by Benlloch et al[136], who recommend an annual head and neck cancer screening due to the high risk of this type of cancer. However, only two studies have shown that intensive screening protocols increase survival[137,138]. Therefore, at the present time, patient education, mainly to avoid smoking and sun exposure, and periodic clinical follow-ups continue to be the standard of care regarding treatment[98].

In the last 10 years, ALD is the LT indication that has seen the greatest increase in prevalence[3] as well as in post-LT survival rate compared with other causes of liver disease, although concerns over alcoholic relapse remain. Even though less than 5% of grafts are rejected at 5 years post-LT due to a direct or indirect consequence of alcohol consumption[139], transplanted ALD patients who relapse have an increased long-term mortality due to cardiovascular pathologies and the onset of de novo neoplasms.

Much has been discussed regarding the risk factors for relapse, and the most controversial has been, and continues to be, the pre-LT abstinence period. In view of the foregoing, we can say that this period by itself should not be a determining factor to include a patient on the list because many other factors exist; therefore, a good psychiatric and psychosocial evaluation that identifies and addresses such factors before and after the LT is important[140,141].

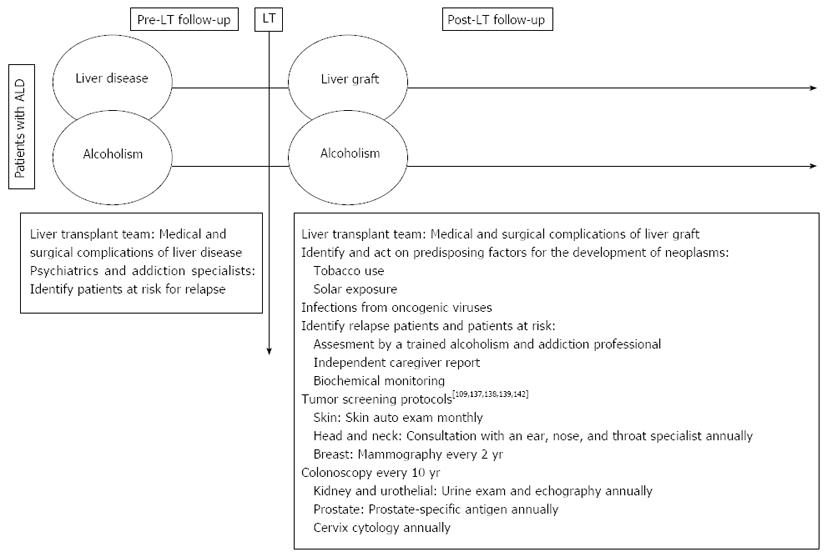

The major incidence of de novo neoplasms in this type of patient could be remedied with the detection of and action on the predisposing factors for the development of neoplasm in addition to the development of more intensive programs for the detection of neoplasm; however, the efficacy of this approach must be demonstrated. What we conclude is that the pre-LT evaluation and the post-LT follow-up in ALD patients should be a multidisciplinary task that includes transplant specialists, psychiatrists and addiction treatment specialists (Figure 2).

P- Reviewers: Biecker E, Ji G, Qin JM, Reshetnyak VI, Sobhonslidsuk A, Teschke R S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | WHO. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2011. Available from: http: //www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/msbgsruprofiles.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Burra P, Senzolo M, Adam R, Delvart V, Karam V, Germani G, Neuberger J. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease in Europe: a study from the ELTR (European Liver Transplant Registry). Am J Transplant. 2010;10:138-148. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Adam R, Karam V, Delvart V, O’Grady J, Mirza D, Klempnauer J, Castaing D, Neuhaus P, Jamieson N, Salizzoni M. Evolution of indications and results of liver transplantation in Europe. A report from the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR). J Hepatol. 2012;57:675-688. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 606] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 590] [Article Influence: 49.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Berg CL, Steffick DE, Edwards EB, Heimbach JK, Magee JC, Washburn WK, Mazariegos GV. Liver and intestine transplantation in the United States 1998-2007. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:907-931. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 142] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Singal AK, Chaha KS, Rasheed K, Anand BS. Liver transplantation in alcoholic liver disease current status and controversies. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5953-5963. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Singal AK, Guturu P, Hmoud B, Kuo YF, Salameh H, Wiesner RH. Evolving frequency and outcomes of liver transplantation based on etiology of liver disease. Transplantation. 2013;95:755-760. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 221] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Varma V, Webb K, Mirza DF. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4377-4393. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Pageaux GP, Perney P, Larrey D. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Addict Biol. 2001;6:301-308. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Corn BW, Moughan J, Knisely JP, Fox SW, Chakravarti A, Yung WK, Curran WJ, Robins HI, Brachman DG, Henderson RH. Prospective evaluation of quality of life and neurocognitive effects in patients with multiple brain metastases receiving whole-brain radiotherapy with or without thalidomide on Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) trial 0118. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:71-78. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dew MA, Switzer GE, Goycoolea JM, Allen AS, DiMartini A, Kormos RL, Griffith BP. Does transplantation produce quality of life benefits? A quantitative analysis of the literature. Transplantation. 1997;64:1261-1273. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Bravata DM, Olkin I, Barnato AE, Keeffe EB, Owens DK. Health-related quality of life after liver transplantation: a meta-analysis. Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:318-331. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Gross CR, Malinchoc M, Kim WR, Evans RW, Wiesner RH, Petz JL, Crippin JS, Klintmalm GB, Levy MF, Ricci P. Quality of life before and after liver transplantation for cholestatic liver disease. Hepatology. 1999;29:356-364. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Pereira SP, Howard LM, Muiesan P, Rela M, Heaton N, Williams R. Quality of life after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:762-768. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Bravata DM, Olkin I, Barnato AE, Keeffe EB, Owens DK. Employment and alcohol use after liver transplantation for alcoholic and nonalcoholic liver disease: a systematic review. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:191-203. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Bravata DM, Keeffe EB. Quality of life and employment after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:S119-S123. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Saab S, Wiese C, Ibrahim AB, Peralta L, Durazo F, Han S, Yersiz H, Farmer DG, Ghobrial RM, Goldstein LI. Employment and quality of life in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1330-1338. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Ruppert K, Kuo S, DiMartini A, Balan V. In a 12-year study, sustainability of quality of life benefits after liver transplantation varies with pretransplantation diagnosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1619-1629, 1629.e1-4. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Mejías D, Ramírez P, Ríos A, Munitiz V, Hernandez Q, Bueno F, Robles R, Torregrosa N, Miras M, Ortiz M. Recurrence of alcoholism and quality of life in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis following liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:2472-2474. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Cowling T, Jennings LW, Goldstein RM, Sanchez EQ, Chinnakotla S, Klintmalm GB, Levy MF. Societal reintegration after liver transplantation: findings in alcohol-related and non-alcohol-related transplant recipients. Ann Surg. 2004;239:93-98. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Adams PC, Ghent CN, Grant DR, Wall WJ. Employment after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1995;21:140-144. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Rongey C, Bambha K, Vanness D, Pedersen RA, Malinchoc M, Therneau TM, Dickson ER, Kim WR. Employment and health insurance in long-term liver transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1901-1908. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Sahota A, Zaghla H, Adkins R, Ramji A, Lewis S, Moser J, Sher LS, Fong TL. Predictors of employment after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2006;20:490-495. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Bravata DM, Keeffe EB, Owens DK. Quality of life, employment and alcohol consumption after liver transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2001;6:130-141. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Vaillant GE. A 60-year follow-up of alcoholic men. Addiction. 2003;98:1043-1051. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Vaillant GE. The natural history of alcoholism and its relationship to liver transplantation. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3:304-310. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Nathan PE. Substance use disorders in the DSM-IV. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:356-361. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Dew MA, DiMartini AF, Steel J, De Vito Dabbs A, Myaskovsky L, Unruh M, Greenhouse J. Meta-analysis of risk for relapse to substance use after transplantation of the liver or other solid organs. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:159-172. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 187] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mackie J, Groves K, Hoyle A, Garcia C, Garcia R, Gunson B, Neuberger J. Orthotopic liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: a retrospective analysis of survival, recidivism, and risk factors predisposing to recidivism. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:418-427. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:399-420. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 431] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | DiMartini A, Day N, Dew MA, Javed L, Fitzgerald MG, Jain A, Fung JJ, Fontes P. Alcohol consumption patterns and predictors of use following liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:813-820. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Anand AC, Ferraz-Neto BH, Nightingale P, Mirza DF, White AC, McMaster P, Neuberger JM. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: evaluation of a selection protocol. Hepatology. 1997;25:1478-1484. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Bellamy CO, DiMartini AM, Ruppert K, Jain A, Dodson F, Torbenson M, Starzl TE, Fung JJ, Demetris AJ. Liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis: long term follow-up and impact of disease recurrence. Transplantation. 2001;72:619-626. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Berlakovich GA, Steininger R, Herbst F, Barlan M, Mittlböck M, Mühlbacher F. Efficacy of liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis with respect to recidivism and compliance. Transplantation. 1994;58:560-565. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Bird GL, O’Grady JG, Harvey FA, Calne RY, Williams R. Liver transplantation in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis: selection criteria and rates of survival and relapse. BMJ. 1990;301:15-17. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Björnsson E, Olsson J, Rydell A, Fredriksson K, Eriksson C, Sjöberg C, Olausson M, Bäckman L, Castedal M, Friman S. Long-term follow-up of patients with alcoholic liver disease after liver transplantation in Sweden: impact of structured management on recidivism. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:206-216. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Cuadrado A, Fábrega E, Casafont F, Pons-Romero F. Alcohol recidivism impairs long-term patient survival after orthotopic liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:420-426. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | DiMartini A, Day N, Dew MA, Lane T, Fitzgerald MG, Magill J, Jain A. Alcohol use following liver transplantation: a comparison of follow-up methods. Psychosomatics. 2001;42:55-62. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Everson G, Bharadhwaj G, House R, Talamantes M, Bilir B, Shrestha R, Kam I, Wachs M, Karrer F, Fey B. Long-term follow-up of patients with alcoholic liver disease who underwent hepatic transplantation. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3:263-274. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Fábrega E, Crespo J, Casafont F, De las Heras G, de la Peña J, Pons-Romero F. Alcoholic recidivism after liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;26:204-206. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 40. | Foster PF, Fabrega F, Karademir S, Sankary HN, Mital D, Williams JW. Prediction of abstinence from ethanol in alcoholic recipients following liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1997;25:1469-1477. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. | Gerhardt TC, Goldstein RM, Urschel HC, Tripp LE, Levy MF, Husberg BS, Jennings LW, Gonwa TA, Klintmalm GB. Alcohol use following liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis. Transplantation. 1996;62:1060-1063. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Gish RG, Lee AH, Keeffe EB, Rome H, Concepcion W, Esquivel CO. Liver transplantation for patients with alcoholism and end-stage liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1337-1342. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | Gish RG, Lee A, Brooks L, Leung J, Lau JY, Moore DH. Long-term follow-up of patients diagnosed with alcohol dependence or alcohol abuse who were evaluated for liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:581-587. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 44. | Gledhill J, Burroughs A, Rolles K, Davidson B, Blizard B, Lloyd G. Psychiatric and social outcome following liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: a controlled study. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46:359-368. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 45. | Howard L, Fahy T, Wong P, Sherman D, Gane E, Williams R. Psychiatric outcome in alcoholic liver transplant patients. QJM. 1994;87:731-736. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 46. | Karman JF, Sileri P, Kamuda D, Cicalese L, Rastellini C, Wiley TE, Layden TJ, Benedetti E. Risk factors for failure to meet listing requirements in liver transplant candidates with alcoholic cirrhosis. Transplantation. 2001;71:1210-1213. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 47. | Knechtle SJ, Fleming MF, Barry KL, Steen D, Pirsch JD, D’Alessandro AM, Kalayoglu M, Belzer FO. Liver transplantation in alcoholics: assessment of psychological health and work activity. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:1916-1918. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 48. | Krom RA. Liver transplantation and alcohol: who should get transplants? Hepatology. 1994;20:28S-32S. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 49. | Kumar S, Stauber RE, Gavaler JS, Basista MH, Dindzans VJ, Schade RR, Rabinovitz M, Tarter RE, Gordon R, Starzl TE. Orthotopic liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1990;11:159-164. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 50. | Lucey MR, Carr K, Beresford TP, Fisher LR, Shieck V, Brown KA, Campbell DA, Appelman HD. Alcohol use after liver transplantation in alcoholics: a clinical cohort follow-up study. Hepatology. 1997;25:1223-1227. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Osorio RW, Ascher NL, Avery M, Bacchetti P, Roberts JP, Lake JR. Predicting recidivism after orthotopic liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1994;20:105-110. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 52. | Pageaux GP, Bismuth M, Perney P, Costes V, Jaber S, Possoz P, Fabre JM, Navarro F, Blanc P, Domergue J. Alcohol relapse after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: does it matter? J Hepatol. 2003;38:629-634. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 53. | Stefanini GF, Biselli M, Grazi GL, Iovine E, Moscatello MR, Marsigli L, Foschi FG, Caputo F, Mazziotti A, Bernardi M. Orthotopic liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: rates of survival, complications and relapse. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:1356-1359. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 54. | Tang H, Boulton R, Gunson B, Hubscher S, Neuberger J. Patterns of alcohol consumption after liver transplantation. Gut. 1998;43:140-145. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 55. | Tome S, Lucey MR. Timing of liver transplantation in alcoholic cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2003;39:302-307. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 56. | Tringali RA, Trzepacz PT, DiMartini A, Dew MA. Assessment and follow-up of alcohol-dependent liver transplantation patients. A clinical cohort. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:70S-77S. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 57. | Yates WR, Labrecque DR, Pfab D. The reliability of alcoholism history in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis. Alcohol Alcohol. 1998;33:488-494. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 58. | Zibari GB, Edwin D, Wall L, Diehl A, Fair J, Burdick J, Klein A. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Clin Transplant. 1996;10:676-679. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 59. | Lucey MR. Liver transplantation in the alcoholic patient. Transplantation of the Liver. Philadelphia, PA: Lipincott Williams and Wilkins 2001; 319-326. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 60. | Schmeding M, Heidenhain C, Neuhaus R, Neuhaus P, Neumann UP. Liver transplantation for alcohol-related cirrhosis: a single centre long-term clinical and histological follow-up. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:236-243. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | DiMartini A, Dew MA, Day N, Fitzgerald MG, Jones BL, deVera ME, Fontes P. Trajectories of alcohol consumption following liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:2305-2312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 144] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Burra P, Germani G, Gnoato F, Lazzaro S, Russo FP, Cillo U, Senzolo M. Adherence in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:760-770. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Berlakovich GA, Langer F, Freundorfer E, Windhager T, Rockenschaub S, Sporn E, Soliman T, Pokorny H, Steininger R, Mühlbacher F. General compliance after liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis. Transpl Int. 2000;13:129-135. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 64. | O’Carroll RE, McGregor LM, Swanson V, Masterton G, Hayes PC. Adherence to medication after liver transplantation in Scotland: a pilot study. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1862-1868. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 65. | Mor E, Gonwa TA, Husberg BS, Goldstein RM, Klintmalm GB. Late-onset acute rejection in orthotopic liver transplantation--associated risk factors and outcome. Transplantation. 1992;54:821-824. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 66. | Hanrahan JS, Eberly C, Mohanty PK. Substance abuse in heart transplant recipients: a 10-year follow-up study. Prog Transplant. 2001;11:285-290. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 67. | Cherubini P, Rumiati R, Bigoni M, Tursi V, Livi U. Long-term decrease in subjective perceived efficacy of immunosuppressive treatment after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:1376-1380. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 68. | Washington AW. Cross-cultural issues in transplant compliance. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:27S-28S. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 69. | Rowe IA, Webb K, Gunson BK, Mehta N, Haque S, Neuberger J. The impact of disease recurrence on graft survival following liver transplantation: a single centre experience. Transpl Int. 2008;21:459-465. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Yusoff IF, House AK, De Boer WB, Ferguson J, Garas G, Heath D, Mitchell A, Jeffrey Gp. Disease recurrence after liver transplantation in Western Australia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:203-207. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 71. | Conjeevaram HS, Hart J, Lissoos TW, Schiano TD, Dasgupta K, Befeler AS, Millis JM, Baker AL. Rapidly progressive liver injury and fatal alcoholic hepatitis occurring after liver transplantation in alcoholic patients. Transplantation. 1999;67:1562-1568. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 72. | Lucey MR. Serial liver biopsies: a gateway into understanding the long-term health of the liver allograft. J Hepatol. 2001;34:762-763. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 73. | Burra P, Mioni D, Cecchetto A, Cillo U, Zanus G, Fagiuoli S, Naccarato R, Martines D. Histological features after liver transplantation in alcoholic cirrhotics. J Hepatol. 2001;34:716-722. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 74. | Rice JP, Eickhoff J, Agni R, Ghufran A, Brahmbhatt R, Lucey MR. Abusive drinking after liver transplantation is associated with allograft loss and advanced allograft fibrosis. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:1377-1386. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 110] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Pageaux GP, Michel J, Coste V, Perney P, Possoz P, Perrigault PF, Navarro F, Fabre JM, Domergue J, Blanc P. Alcoholic cirrhosis is a good indication for liver transplantation, even for cases of recidivism. Gut. 1999;45:421-426. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 76. | Van Thiel DH, Bonet H, Gavaler J, Wright HI. Effect of alcohol use on allograft rejection rates after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1151-1155. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 77. | Berlakovich GA, Imhof M, Karner-Hanusch J, Gotzinger P, Gollackner B, Gnant M, Hanelt S, Laufer G, Muhlbacher F, Steininger R. The importance of the effect of underlying disease on rejection outcomes following orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1996;61:554-560. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 78. | Lucey MR, Merion RM, Henley KS, Campbell DA, Turcotte JG, Nostrant TT, Blow FC, Beresford TP. Selection for and outcome of liver transplantation in alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1736-1741. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 79. | Jain A, DiMartini A, Kashyap R, Youk A, Rohal S, Fung J. Long-term follow-up after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease under tacrolimus. Transplantation. 2000;70:1335-1342. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 80. | Jiménez C, Marqués E, Loinaz C, Romano DR, Gómez R, Meneu JC, Hernández-Vallejo G, Alonso O, Abradelo M, Garcia I. Upper aerodigestive tract and lung tumors after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1900-1901. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 81. | Nure E, Frongillo F, Lirosi MC, Grossi U, Sganga G, Avolio AW, Siciliano M, Addolorato G, Mariano G, Agnes S. Incidence of upper aerodigestive tract cancer after liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis: a 10-year experience in an Italian center. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:2733-2735. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Faure S, Herrero A, Jung B, Duny Y, Daures JP, Mura T, Assenat E, Bismuth M, Bouyabrine H, Donnadieu-Rigole H. Excessive alcohol consumption after liver transplantation impacts on long-term survival, whatever the primary indication. J Hepatol. 2012;57:306-312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Pfitzmann R, Schwenzer J, Rayes N, Seehofer D, Neuhaus R, Nüssler NC. Long-term survival and predictors of relapse after orthotopic liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:197-205. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 84. | Coffman KL, Hoffman A, Sher L, Rojter S, Vierling J, Makowka L. Treatment of the postoperative alcoholic liver transplant recipient with other addictions. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3:322-327. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 85. | Kelly M, Chick J, Gribble R, Gleeson M, Holton M, Winstanley J, McCaughan GW, Haber PS. Predictors of relapse to harmful alcohol after orthotopic liver transplantation. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:278-283. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 86. | Jauhar S, Talwalkar JA, Schneekloth T, Jowsey S, Wiesner RH, Menon KV. Analysis of factors that predict alcohol relapse following liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:408-411. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 87. | McCallum S, Masterton G. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: a systematic review of psychosocial selection criteria. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:358-363. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Kotlyar DS, Burke A, Campbell MS, Weinrieb RM. A critical review of candidacy for orthotopic liver transplantation in alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:734-743; quiz 744. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 89. | Perney P, Bismuth M, Sigaud H, Picot MC, Jacquet E, Puche P, Jaber S, Rigole H, Navarro F, Eledjam JJ. Are preoperative patterns of alcohol consumption predictive of relapse after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease? Transpl Int. 2005;18:1292-1297. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 90. | De Gottardi A, Spahr L, Gelez P, Morard I, Mentha G, Guillaud O, Majno P, Morel P, Hadengue A, Paliard P. A simple score for predicting alcohol relapse after liver transplantation: results from 387 patients over 15 years. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1183-1188. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 91. | Karim Z, Intaraprasong P, Scudamore CH, Erb SR, Soos JG, Cheung E, Cooper P, Buzckowski AK, Chung SW, Steinbrecher UP. Predictors of relapse to significant alcohol drinking after liver transplantation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:245-250. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 92. | Shawcross DL, O’Grady JG. The 6-month abstinence rule in liver transplantation. Lancet. 2010;376:216-217. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Anantharaju A, Van Thiel DH. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:257-268. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 94. | Veldt BJ, Lainé F, Guillygomarc’h A, Lauvin L, Boudjema K, Messner M, Brissot P, Deugnier Y, Moirand R. Indication of liver transplantation in severe alcoholic liver cirrhosis: quantitative evaluation and optimal timing. J Hepatol. 2002;36:93-98. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 95. | Tandon P, Goodman KJ, Ma MM, Wong WW, Mason AL, Meeberg G, Bergsten D, Carbonneau M, Bain VG. A shorter duration of pre-transplant abstinence predicts problem drinking after liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1700-1706. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 96. | Dunn W, Jamil LH, Brown LS, Wiesner RH, Kim WR, Menon KV, Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Shah V. MELD accurately predicts mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 2005;41:353-358. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 97. | Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, Ramond MJ, Diaz E, Fartoux L, Dharancy S, Texier F, Hollebecque A, Serfaty L. The Lille model: a new tool for therapeutic strategy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Hepatology. 2007;45:1348-1354. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 98. | Chandok N, Watt KD. Burden of de novo malignancy in the liver transplant recipient. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:1277-1289. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Watt KD, Pedersen RA, Kremers WK, Heimbach JK, Sanchez W, Gores GJ. Long-term probability of and mortality from de novo malignancy after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:2010-2017. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 100. | Pruthi J, Medkiff KA, Esrason KT, Donovan JA, Yoshida EM, Erb SR, Steinbrecher UP, Fong TL. Analysis of causes of death in liver transplant recipients who survived more than 3 years. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:811-815. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 101. | Watt KD, Pedersen RA, Kremers WK, Heimbach JK, Charlton MR. Evolution of causes and risk factors for mortality post-liver transplant: results of the NIDDK long-term follow-up study. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1420-1427. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 537] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Duvoux C, Delacroix I, Richardet JP, Roudot-Thoraval F, Métreau JM, Fagniez PL, Dhumeaux D, Cherqui D. Increased incidence of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas after liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis. Transplantation. 1999;67:418-421. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 103. | Haagsma EB, Hagens VE, Schaapveld M, van den Berg AP, de Vries EG, Klompmaker IJ, Slooff MJ, Jansen PL. Increased cancer risk after liver transplantation: a population-based study. J Hepatol. 2001;34:84-91. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 104. | Nakajima T, Kamijo Y, Tanaka N, Sugiyama E, Tanaka E, Kiyosawa K, Fukushima Y, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Aoyama T. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha protects against alcohol-induced liver damage. Hepatology. 2004;40:972-980. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 105. | Seitz HK, Stickel F. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-mediated carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:599-612. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 106. | Saigal S, Norris S, Muiesan P, Rela M, Heaton N, O’Grady J. Evidence of differential risk for posttransplantation malignancy based on pretransplantation cause in patients undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:482-487. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 107. | Watson RR. Ethanol, immunomodulation and cancer. Prog Food Nutr Sci. 1988;12:189-209. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 108. | Roselle G, Mendenhall CL, Grossman CJ. Effects of alcohol on immunity and cancer. Alcohol, immunity, and cancer. Boca Raton, FL: CRC 1993; 3-21. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 109. | Herrero JI, Lorenzo M, Quiroga J, Sangro B, Pardo F, Rotellar F, Alvarez-Cienfuegos J, Prieto J. De Novo neoplasia after liver transplantation: an analysis of risk factors and influence on survival. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:89-97. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 110. | Burling TA, Ziff DC. Tobacco smoking: a comparison between alcohol and drug abuse inpatients. Addict Behav. 1988;13:185-190. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 111. | Burling TA; SAMHSA. Findings from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMH-SA), Office of Applied Studies, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2012. Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2012SummNatFindDetTables/. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 112. | Ehlers SL, Rodrigue JR, Widows MR, Reed AI, Nelson DR. Tobacco use before and after liver transplantation: a single center survey and implications for clinical practice and research. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:412-417. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 113. | Pungpapong S, Manzarbeitia C, Ortiz J, Reich DJ, Araya V, Rothstein KD, Muñoz SJ. Cigarette smoking is associated with an increased incidence of vascular complications after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:582-587. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 114. | DiMartini A, Javed L, Russell S, Dew MA, Fitzgerald MG, Jain A, Fung J. Tobacco use following liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: an underestimated problem. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:679-683. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 115. | Rubio E, Moreno JM, Turrión VS, Jimenez M, Lucena JL, Cuervas-Mons V. De novo malignancies and liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1896-1897. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 116. | Scheifele C, Reichart PA, Hippler-Benscheidt M, Neuhaus P, Neuhaus R. Incidence of oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas among 1515 patients after liver transplantation. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:670-676. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 117. | Jiménez C, Manrique A, Marqués E, Ortega P, Loinaz C, Gómez R, Meneu JC, Abradelo M, Moreno A, López A. Incidence and risk factors for the development of lung tumors after liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2007;20:57-63. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 118. | Dumortier J, Guillaud O, Adham M, Boucaud C, Delafosse B, Bouffard Y, Paliard P, Scoazec JY, Boillot O. Negative impact of de novo malignancies rather than alcohol relapse on survival after liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis: a retrospective analysis of 305 patients in a single center. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1032-1041. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 119. | Chak E, Saab S. Risk factors and incidence of de novo malignancy in liver transplant recipients: a systematic review. Liver Int. 2010;30:1247-1258. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 94] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | van der Heide F, Dijkstra G, Porte RJ, Kleibeuker JH, Haagsma EB. Smoking behavior in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:648-655. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Corbett C, Armstrong MJ, Neuberger J. Tobacco smoking and solid organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2012;94:979-987. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Herrero JI, Pardo F, D’Avola D, Alegre F, Rotellar F, Iñarrairaegui M, Martí P, Sangro B, Quiroga J. Risk factors of lung, head and neck, esophageal, and kidney and urinary tract carcinomas after liver transplantation: the effect of smoking withdrawal. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:402-408. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 123. | Borg MA, van der Wouden EJ, Sluiter WJ, Slooff MJ, Haagsma EB, van den Berg AP. Vascular events after liver transplantation: a long-term follow-up study. Transpl Int. 2008;21:74-80. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 124. | Doyon WM, Dong Y, Ostroumov A, Thomas AM, Zhang TA, Dani JA. Nicotine decreases ethanol-induced dopamine signaling and increases self-administration via stress hormones. Neuron. 2013;79:530-540. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 125. | Georgiou G, Webb K, Griggs K, Copello A, Neuberger J, Day E. First report of a psychosocial intervention for patients with alcohol-related liver disease undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:772-775. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 126. | Addolorato G, Mirijello A, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, D’Angelo C, Vassallo G, Cossari A, Gasbarrini G, Landolfi R, Agnes S, Gasbarrini A; Gemelli OLT Group. Liver transplantation in alcoholic patients: impact of an alcohol addiction unit within a liver transplant center. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:1601-1608. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 130] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 127. | Allen JP, Wurst FM, Thon N, Litten RZ. Assessing the drinking status of liver transplant patients with alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:369-376. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 128. | Helander A, Eriksson CJ. Laboratory tests for acute alcohol consumption: results of the WHO/ISBRA Study on State and Trait Markers of Alcohol Use and Dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1070-1077. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 129. | Conigrave KM, Degenhardt LJ, Whitfield JB, Saunders JB, Helander A, Tabakoff B; WHO/ISBRA Study Group. CDT, GGT, and AST as markers of alcohol use: the WHO/ISBRA collaborative project. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:332-339. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 130. | Stibler H. Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin in serum: a new marker of potentially harmful alcohol consumption reviewed. Clin Chem. 1991;37:2029-2037. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 131. | Javors MA, Johnson BA. Current status of carbohydrate deficient transferrin, total serum sialic acid, sialic acid index of apolipoprotein J and serum beta-hexosaminidase as markers for alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2003;98 Suppl 2:45-50. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 132. | Staufer K, Andresen H, Vettorazzi E, Tobias N, Nashan B, Sterneck M. Urinary ethyl glucuronide as a novel screening tool in patients pre- and post-liver transplantation improves detection of alcohol consumption. Hepatology. 2011;54:1640-1649. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 133. | Wurst FM, Skipper GE, Weinmann W. Ethyl glucuronide--the direct ethanol metabolite on the threshold from science to routine use. Addiction. 2003;98 Suppl 2:51-61. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 134. | Thierauf A, Halter CC, Rana S, Auwaerter V, Wohlfarth A, Wurst FM, Weinmann W. Urine tested positive for ethyl glucuronide after trace amounts of ethanol. Addiction. 2009;104:2007-2012. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 135. | Sterneck M, Yegles M, von Rothkirch G, Staufer K, Vettorazzi E, Schulz KH, Tobias N, Graeser C, Fischer L, Nashan B. Determination of ethyl glucuronide in hair improves evaluation of long-term alcohol abstention in liver transplant candidates. Liver Int. 2013;Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 136. | Benlloch S, Berenguer M, Prieto M, Moreno R, San Juan F, Rayón M, Mir J, Segura A, Berenguer J. De novo internal neoplasms after liver transplantation: increased risk and aggressive behavior in recent years? Am J Transplant. 2004;4:596-604. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 137. | Finkenstedt A, Graziadei IW, Oberaigner W, Hilbe W, Nachbaur K, Mark W, Margreiter R, Vogel W. Extensive surveillance promotes early diagnosis and improved survival of de novo malignancies in liver transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2355-2361. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 138. | Herrero JI, Alegre F, Quiroga J, Pardo F, Iñarrairaegui M, Sangro B, Rotellar F, Montiel C, Prieto J. Usefulness of a program of neoplasia surveillance in liver transplantation. A preliminary report. Clin Transplant. 2009;23:532-536. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 139. | Poynard T, Naveau S, Doffoel M, Boudjema K, Vanlemmens C, Mantion G, Messner M, Launois B, Samuel D, Cherqui D. Evaluation of efficacy of liver transplantation in alcoholic cirrhosis using matched and simulated controls: 5-year survival. Multi-centre group. J Hepatol. 1999;30:1130-1137. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 140. | Rodrigue JR, Hanto DW, Curry MP. Substance abuse treatment and its association with relapse to alcohol use after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 141. | Campistol JM, Cuervas-Mons V, Manito N, Almenar L, Arias M, Casafont F, Del Castillo D, Crespo-Leiro MG, Delgado JF, Herrero JI. New concepts and best practices for management of pre- and post-transplantation cancer. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2012;26:261-279. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |