Published online Jan 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.152

Revised: September 25, 2007

Published online: January 7, 2008

We reported a case of huge gastric phytobezoar. The gastric phytobezoar was successfully removed through gastrotomy after two failed attempts in endoscopic fragmentation and removal. Disopyrobezoars could be treated either conservatively or surgically. Gastrotomy or laparoscopical management is recommended for the treatment of huge disopyrobezoars.

- Citation: Zhang RL, Yang ZL, Fan BG. Huge gastric disopyrobezoar: A case report and review of literatures. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(1): 152-154

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i1/152.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.152

Phytobezoars are common bezoars in the gastrointestinal tract, including stomach and small intestine[1], but huge disopyrobezoars are rarely seen clinically. We report a case of huge disopyrobezoar (18 cm × 7.5 cm × 7cm), a kind of phytobezoar caused by persimmon, and to present our experience while reviewing the literature.

A 47-year-old man presented with complaints of acute aggravated epigastric distention and pain for half a month after one year of persistent epigastric distention and acid regurgitation, which were uninfluenced by ingesting food. There were no obvious symptoms of gastrointestinal obstruction, e.g., nausea or vomiting. The patient had a long history of overindulgence of bitter persimmons from childhood without the history of gastric surgery.

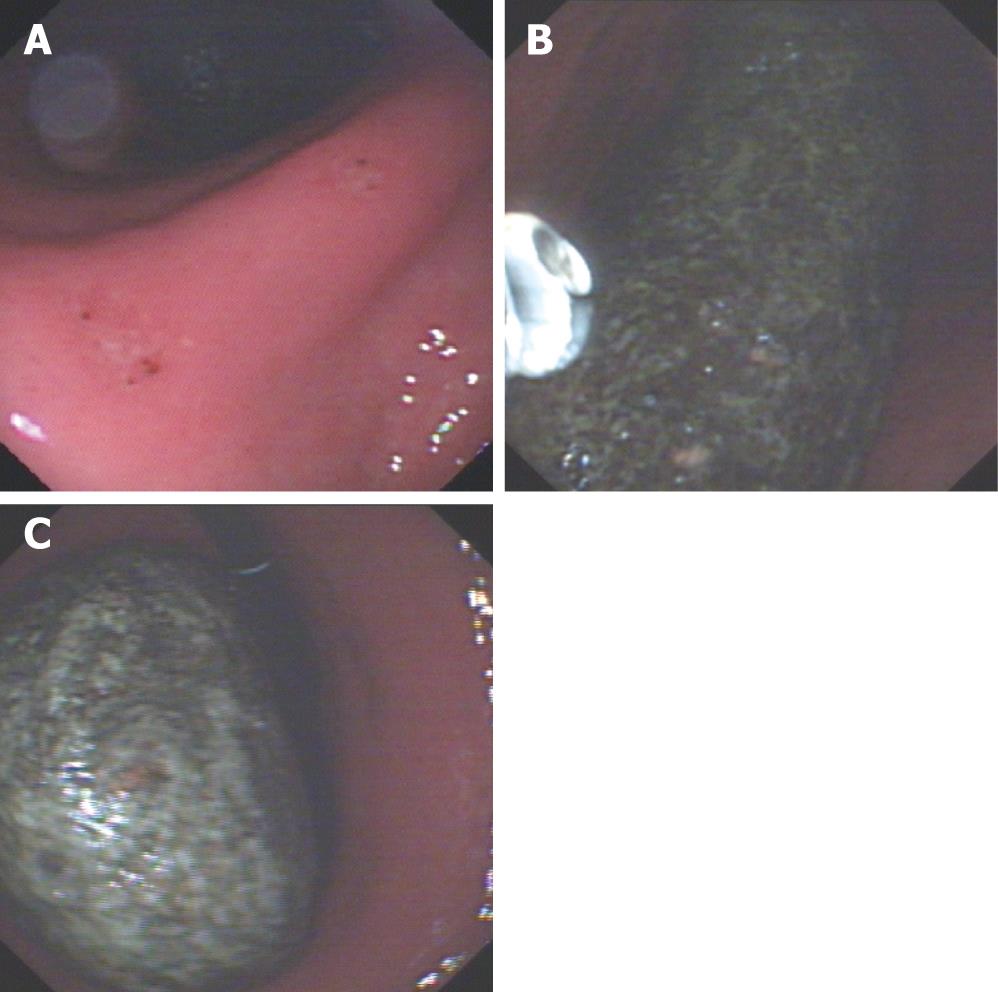

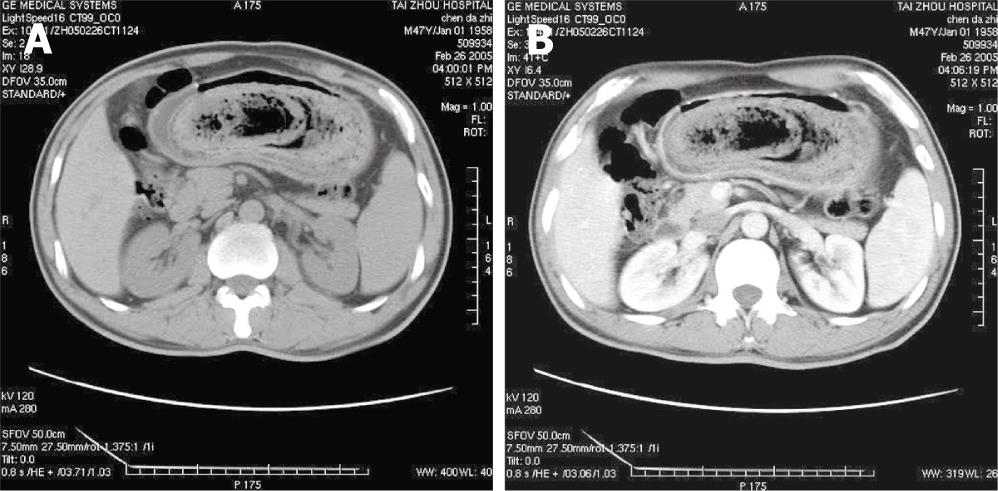

On physical examination, a solid, movable ellipse mass could be palpated in the left epigastrium and the abdomen was soft. Gastroscopical examination showed a giant brown solid gastric bezoar of 15 cm × 7 cm in size (Figure 1), chronic superficial gastritis as well as two erosions at the corner of the stomach, which were pathologically proven to be chronic superficial active membraneous inflammation. Abdominal computerized tomography revealed a mass-like occupational lesion within the stomach (18 cm long and 7 cm in diameter) with air bubbles retained in its interstices and mottled appearance, compatible with the features of bezoars (Figure 2). The patient was then admitted to the department of gastroenterology of our hospital.

On the 3rd day after admission to hospital, endoscopy (Fujinon EG 250 WR 5, Fuji Photo Optical Company Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was used to fragment the huge bezoar with a mouse-teeth clamp and snare, but it was unsuccessful to extract the bezoar despite the help of gastric lavage using sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) because the bezoar was too hard and big. On the 4th d, another attempt of endoscopical fragmentation and extraction procedure also failed. On the 5th day, the patient was transferred to the department of general surgery for operation after two failed attempts in endoscopic fragmentation and removal of the gastric bezoar.

Gastrotomy was performed on the patient and a huge grey ellipse bezoar (18 cm × 7.5 cm × 7 cm) was removed from the gastric lumen (Figure 3). A piece of the bezoar obtained during endoscopy was analyzed by infrared spectroscopy, which revealed that 85% of them was composed of tannin and 10% was cellulose, therefore, the bezoar was considered as disopyrobezoar derived from bitter persimmon. The patient was discharged on the 7th postoperative day. During the 6-month follow-up, the patient did not complain of any discomfort and the two concomitant erosions healed uneventfully on medical therapy shown by another gastroscopy.

Bezoars are classified according to their composition into phytobezoar, trichobezoar (hair), lactobezoar (concentrated milk formulas), mixed medication bezoar and food bolus bezoar[2]. Phytobezoars are composed of indigestible cellulose, tannin and lignin derived from ingested vegetables and fruits[3].

A disopyrobezoar is a type of phytobezoar caused by persimmons, although it is an infrequent entity in clinic, and not rare in some countries[4]. Disopyrobezoars are generated by over-ingestion of unripe or astringent persimmons containing rich soluble tannin and shibuol especially in free stomach. In the presence of the dilute hydrochloric acid in the stomach, the tannin undergoes polymerization to a coagulum that includes cellulose, hemicellulose, and protein, which is the basis of the bezoar[5].

Disopyrobezoar formation is commonly associated with previous gastric surgery (truncal vagotomy plus pyloroplasty or subtotal gastrectomy plus gastroen-terostomy), dental problems, poor mastication, and overindulgence of persimmon[4]. Gastric operations may reduce gastric motor activity and delay gastric emptying. Loss of pyloric function, gastric motility and hypoacidity plays an important role in the formation of disopyrobezoar[6]. Diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism were also reported as predisposing factors of disopyrobezoar formation because they could delay gastric emptying[7]. Our patient had a long indulgence history of bitter persimmon intake, resulting in the formation of the huge disopyrobezoar.

Clinical manifestations vary with the location of disopyrobezoar from no symptom to acute abdominal syndrome, e.g., epigastric distention, abdominal pain and acid regurgitation. Gastric disopyrobezoars are sometimes associated with gastric ulcer formation. When located in small bowel, they often cause small bowel obstruction (SBO)[14], presenting with nausea, vomiting and abdominal distention. Major complications of disopyrobezoars include intestinal obstruction, gastric perforation, gastric ulcer and gastritis[5]. Abdominal pain (49%-100%), epigastric distress (80%), anorexia, vomiting and nausea (35%-78%), and SBO (94.73%) are the main clinical symptoms[8]. Feelings of fullness and dysphagia with weight loss and even gastrointestinal hemorrhage could also be seen[2]. When complicated with SBO, diminished peristaltic sounds, rebounding pain and tenderness, distention, vomiting and abdominal pain could be found clinically, elevated leukocyte count up to 28.000/mm3 and fever could also be detected[5]. In this study, the patient presented epigastric distention, epigastric pain and acid regurgitation.

As for the radiographic diagnosis, about 50%-75% of the SBO cases could be diagnosed by plain abdominal radiography[9]. CT-scan could demonstrate a well-defined round mass which could be outlined by stomach or the bowel wall and present characteristic internal gas bubbles of bezoars[10]. Abdominal ultrasonography could suggest hyperechoic arclike surface and marked posterior acoustic shadow of the gastric bezoars within the lumen of stomach and small bowel, and barium study could demonstrate intraluminally filling defect as well as mottled appearance of the bezoar. Endoscopic investigations could almost show and confirm all of gastric bezoars[11].

The ultimate goal of the treatment of gastrointestinal disopyrobezoars is the removal of the lesion and prevention of recurrence. Disopyrobezoars can be treated by conservative modalities (gastric lavage, endoscopic disruption, etc.) and conventional surgery as well as videolaparoscopic surgery[412]. But disopyrobezoars are often resistant to drug treatment because they are much harder than other kinds of phytobezoars, hence being usually removed endoscopically or surgically. Gastric lavage has been reported for the treatment of disopyrobezoars using NaHCO3 which has a mucolytic effect, and penetration of CO2 bubbles into the surface of bezoars could digest the fibres of concretion[6]; and most interestingly, a successful nasogastric Coca-Cola lavage treatment for gastric disopyrobezoars was reported[13].

The side effects of conservative treatment of bezoars are gastric ulcer, SBO, hyperosmolar natremia, hemorrhagic pulmonary edema, pharyngeal abscess, endo-tracheal tube obstruction, esophago-gastric iatrogenic injuries (including perforation, laceration, hematoma and ulceration), vocal cord damage and so on[11].

The first step of endoscopic procedure is to determine whether the pylorus appears anatomically normal and to verify the absence of duodenal stricture before fragmenting disopyrobezoars[4]. If a disopyrobezoar is not too large, it can be extracted by a basket or direct suction. If it is big and pylorus is normal, fragmentation can be performed with large polypectomy snare, electrosurgical knife, endoscopic laser destruction and electrohydraulic lithotripsy as well as extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy[14]. Once the disopyrobezoar is fragmented, the patient can be treated by combined use of cellulase and metoclopramide, cellulase and papain, water jet and lavage with NaHCO3 as well[4].

In conventional surgery, bezoar removal is commonly done by gastrotomy and/or enterotomy. If complicated with SBO, gastric perforation or gastric hemorrhage, the patients can be treated by gastric and/or intestinal resections. Our patient had a huge solid gastric disopyrobezoar that was extracted by gastrotomy after two failed attempts of bezoar removal by endoscopical fragmentation and dissolution by NaHCO3 gastric lavage. Moreover, the laparoscopic approach may be the treatment of choice when surgery is indicated. When expertise is available, laparoscopy is safe and effective in the management of bezoar-induced SBO and yields superior postoperative outcomes when compared with conventional open approach[15].

In conclusion, disopyrobezoar is a kind of phyto-bezoar. Plain abdominal radiography, barium studies, ultrasonography, CT-scan and endoscopy are helpful in the diagnosis of disopyrobezoars, while endoscopy can confirm its diagnosis. Disopyrobezoars could be treated either conservatively or surgically. Gastrotomy or laparoscopical manipulation is recommended for the treatment of huge disopyrobezoars.

| 1. | Erzurumlu K, Malazgirt Z, Bektas A, Dervisoglu A, Polat C, Senyurek G, Yetim I, Ozkan K. Gastrointestinal bezoars: a retrospective analysis of 34 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1813-1817. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Andrus CH, Ponsky JL. Bezoars: classification, pathophysiology, and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:476-478. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Gorgone S, Di Pietro N, Rizzo AG, Melita G, Calabro G, Sano M, De Luca M, Barbuscia M. Mechanical intestinal occlusion due to phytobezoars. G Chir. 2003;24:239-242. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Gaya J, Barranco L, Llompart A, Reyes J, Obrador A. Persimmon bezoars: a successful combined therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:581-583. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Krausz MM, Moriel EZ, Ayalon A, Pode D, Durst AL. Surgical aspects of gastrointestinal persimmon phytobezoar treatment. Am J Surg. 1986;152:526-530. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Saeed ZA, Rabassa AA, Anand BS. An endoscopic method for removal of duodenal phytobezoars. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:74-76. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Ahn YH, Maturu P, Steinheber FU, Goldman JM. Association of diabetes mellitus with gastric bezoar formation. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:527-528. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Toccaceli S, Donfrancesco A, Stella LP, Diana M, Dandolo R, Di Schino C. Shall bowel obstruction caused by phytobezoar. Case report. G Chir. 2005;26:218-220. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Ripollés T, García-Aguayo J, Martínez MJ, Gil P. Gastroin-testinal Bezoars: Sonographic and CT Characteristics. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:65-69. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Kim JH, Ha HK, Sohn MJ, Kim AY, Kim TK, Kim PN, Lee MG, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Jung HY. CT findings of phytobezoar associated with small bowel obstruction. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:299-304. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Blam ME, Lichtenstein GR. A new endoscopic technique for the removal of gastric phytobezoars. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:404-408. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Yol S, Bostanci B, Akoglu M. Laparoscopic treatment of small bowel phytobezoar obstruction. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2003;13:325-326. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Kato H, Nakamura M, Orito E, Ueda R, Mizokami M. The first report of successful nasogastric Coca-Cola lavage treatment for bitter persimmon phytobezoars in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1662-1663. [Cited in This Article: ] |