Published online Nov 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5380

Peer-review started: July 11, 2020

First decision: August 22, 2020

Revised: August 30, 2020

Accepted: September 17, 2020

Article in press: September 17, 2020

Published online: November 6, 2020

Pancreatic cancer with ovarian metastases is rare and easily misdiagnosed. Most patients are first diagnosed with ovarian cancer. We report a rare case of ovarian metastases secondary to pancreatic adenocarcinoma. We also review the literature to analyze the clinical characteristics of, diagnostic methods for, and perioperative management strategies for this rare malignancy.

A 48-year-old woman with an abdominal mass presented to our hospital. Computed tomography revealed lesions in the pancreas and lower abdomen. Radiological examination and histological investigation of biopsy specimens revealed either an ovarian metastasis from a pancreatic neoplasm or two primary tumors, with metastasis strongly suspected. The patient simultaneously underwent distal pancreatectomy plus splenectomy by a general surgeon and salpingo-oophorectomy with hysterectomy by a gynecologist. Histological examination of the surgical specimen revealed a pancreatic adenocarcinoma (intermediate differentiation, mucinous) and a metastatic mucinous adenocarci-noma in the ovary.

For this rare tumor, surgical resection is the most effective treatment, and the final diagnosis depends on tumor pathology.

Core Tip: We report a case of pancreatic adenocarcinoma with ovarian metastasis. Pancreatic cancer with ovarian metastases is asymptomatic in the early stages, progressing rapidly thereafter. Systematic guidelines for this disease are currently lacking. Many patients have been diagnosed with ovarian tumors without obvious abdominal symptoms, which demonstrates the challenge of detecting pancreatic malignancies early. Surgery is the optimal treatment, and pathological examination of the surgical specimen can reveal the final diagnosis. Prognosis depends on pathological type and stage. Clinicians should consider these factors while treating patients with similar symptoms. Early diagnosis of this disease will help in developing an effective treatment strategy.

- Citation: Wang SD, Zhu L, Wu HW, Dai MH, Zhao YP. Pancreatic cancer with ovarian metastases: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(21): 5380-5388

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i21/5380.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5380

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death and has a dismal prognosis. Approximately 20% of patients who present with local disease may show long-term survival, and only radical operation can be an optimal treatment to improve the prognosis[1]. PC tends to metastasize through the lymphoid system to organs such as the lung, liver, bone, and spleen[2]. However, PC with ovarian metastases is rare. PC that has metastasized to the ovaries is found in 4%-6% of patients during autopsy, but it is rarely diagnosed clinically[3-5]. Patients with an ovarian metastasis generally have no distinguishing clinical symptoms or signs[6-8]. Since PC is easy to misdiagnose in clinical practice, the accuracy of clinical diagnoses, reasonable therapeutic methods, perioperative management, and overall survival in those with PC are unclear. Herein, we report a case of PC with ovarian metastases and review previously reported cases.

A 48-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital because of a palpable mass in the lower abdomen.

She denied the presence of abdominal pain, abdominal distention, diarrhea, or dyspepsia without weight loss. Her appetite was not affected.

She denied any history of hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes, or coronary heart disease. She reported no history of smoking, alcohol intake, or a hereditary disorder.

Abdominal examination showed that her abdomen was diffusely soft, with no distention or tenderness. No other positive sign was observed.

Upon admission, her routine blood test results and blood biochemical parameters were normal. Her serum carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 level was 251 U/mL, and her serum CA125 level was 412 U/mL. The levels of other tumor markers, including CA242, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and CA724, were within the normal ranges.

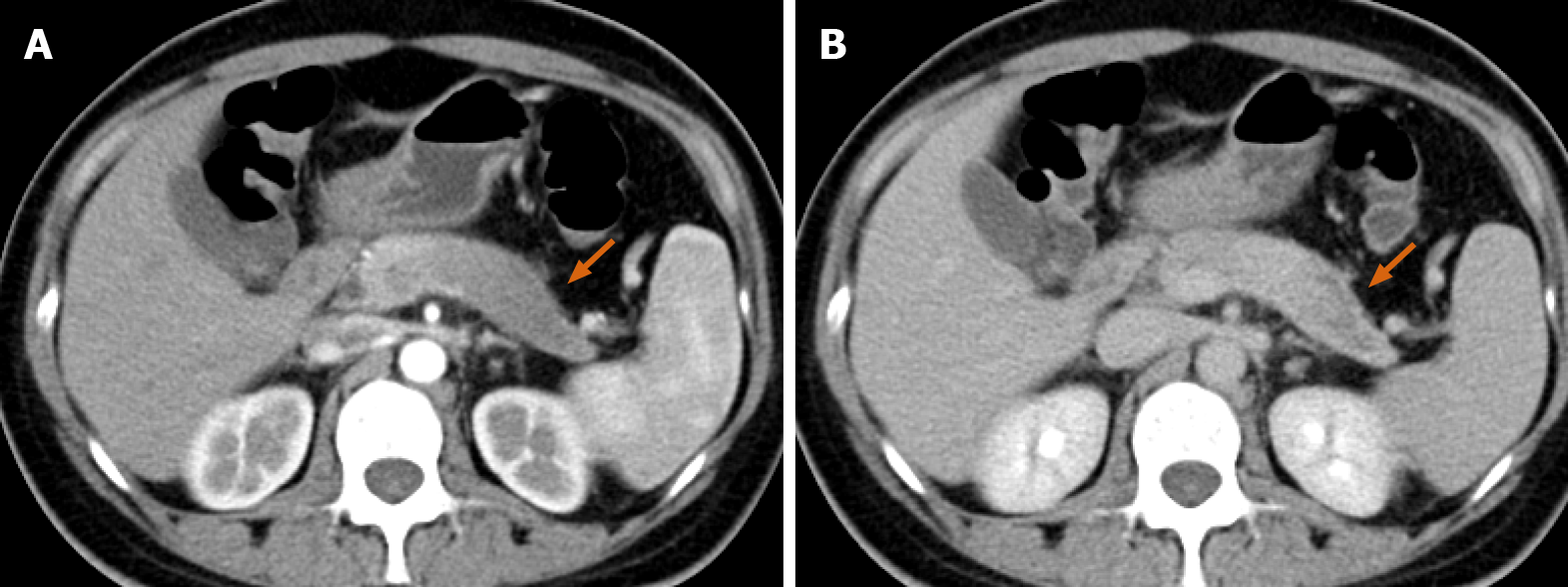

Abdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a low-density lesion measuring 5.9 cm × 4.6 cm with a poorly defined margin and an irregular contour in the tail of the pancreas. The lesion was hypo-enhanced in the pancreatic parenchyma phase, with progressive delayed enhancement; this possibly indicated a pancreatic tumor (Figure 1). Additionally, a cystic-solid mass measuring 15.1 cm × 12.0 cm in the right ovary and a cystic mass measuring 5.7 cm × 4.3 cm in the left ovary were detected in the pelvic cavity. Both masses were thin-walled and had multiple enhancing septa. There was no evidence of liver or peritoneal metastases (Figure 2).

The initial diagnosis was uncertain, but the focus was on pancreatic or ovarian cancer. Therefore, she underwent fine-needle biopsy of lesions after a consultation of doctors. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle (22 gauge) biopsies of the lesion in the pancreatic tail revealed that there was an infiltrative heterogenic glandular growth in the fibrous tissue. And the ultrasound-guided biopsy of the ovary indicated the mass was likely to be metastatic. Immunohistochemistry showed the following findings: CK20 (+), CK7 (+), CDX2 (-), ER (-), and PR (-). The multidisciplinary team considered this pancreatic tumor to be possibly resectable or borderline resectable with ovarian metastases.

A provisional diagnosis of PC with ovarian metastases was made.

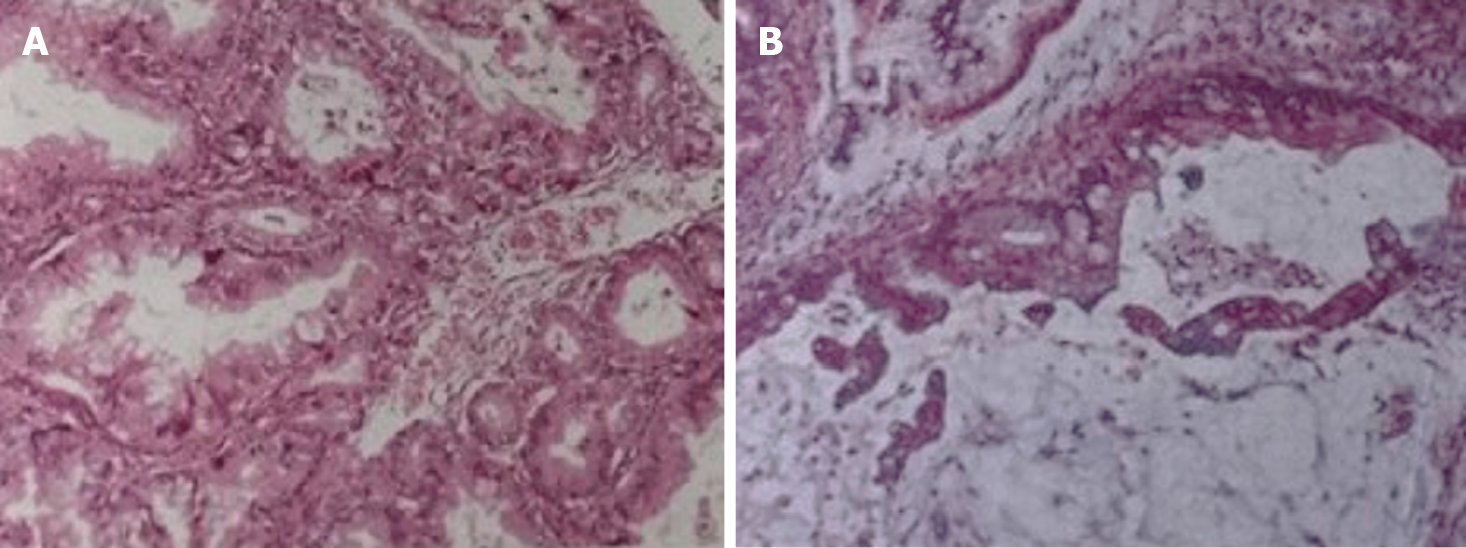

The patient underwent surgeries performed by doctors from the Department of General Surgery and Gynecology. She underwent distal pancreatectomy plus splenectomy as well as salpingo-oophorectomy with hysterectomy. In addition, the appendix and omentum were removed. During the surgery, a mass measuring 4 cm × 3.5 cm was observed in the tail of the pancreas and the hilum of the spleen (Figure 3). It had invaded the spleen parenchyma. Immunohistochemical examination of the pancreatic tumor revealed the following results: CEA (-), CK20 (+), CK7 (+), p53 (-), CA125 (+), and CDX (+). Postoperative pathology revealed the pancreatic mass to be a pancreatic adenocarcinoma (intermediate differentiation, mucinous), and the ovarian masses were correspondingly diagnosed as metastases from the pancreatic mucinous adenocarcinoma. The metastatic cystic-solid mass in the ovary was found to contain many mucinous cysts and a solid component that was gray-pink in color and gel like in consistency (Figure 3). The immunohistochemical characteristics of the ovarian tumor were as follows: CDX2 (-), CK20 (+), CK7 (+), CEA (+), EMA (+), ER (-), PR (-), p53 (-), and CA125 (-) (Figure 4).

She had an uneventful recovery after surgery, and her postoperative hospital stay was 13 d long. Postoperative chemotherapy was advised; however, the patient’s intestinal function was significantly inhibited after chemotherapy, and she did not receive any subsequent chemotherapy. Ultimately, the patient died after 3.5 mo of follow-up.

PC with ovarian metastases has seldom been reported. To investigate this rare disease, we systematically searched the literature databases up till 2020. The keywords used were “Pancreatic carcinoma/cancer/adenocarcinoma,” “ovarian carcinoma/cancer,” “ovarian metastasis,” and “ovary.” In addition, the reference list of each paper was also analyzed. The inclusion criteria were any form of publication focusing on PC with ovarian metastases and a sufficient description of clinicopathological characteristics. Studies published in languages other than English, those with duplicate data from the same patient, and those for which the full text was unavailable were excluded.

The systematic search yielded five studies comprising 31 patients[4,9-12]. The patient in our article was the 32nd reported case. Our case report was the only one that reported the complete pathology and immunohistochemistry results for both the pancreatic and ovarian lesions. The characteristics of all cases are summarized in Table 1. The summary and analysis of the clinicopathological characteristics from these cases should provide a comprehensive description for surgeons and gynecologists.

| Characteristic | Number |

| Age (yr) | 24-83 |

| Symptoms | |

| Abdominal pain | 4 |

| Abdominal mass | 4 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 1 |

| Weight loss | 1 |

| Jaundice | 1 |

| Abdominal distension | 1 |

| Anorexia | 2 |

| NG | 18 |

| Ovarian metastasis at initial presentation | |

| Yes | 21 |

| No | 5 |

| NG | 6 |

| Synchronously or metachronous | |

| Yes | 15 |

| No | 14 |

| NG | 3 |

| Location of pancreatic tumor | |

| Head | 4 |

| Body and tail | 20 |

| NG | 8 |

| Pathology of pancreas | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 20 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 8 |

| Acinar cell carcinoma | 4 |

| Laterality of ovarian metastasis | |

| Bilateral | 22 |

| Unilateral | 10 |

| Pancreatic surgery | |

| Pancreatectomy | 5 |

| Puncture of pancreas | 4 |

| NG | 23 |

| Ovarian surgery | |

| Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy without hysterectomy | 13 |

| Single salpingo-oophorectomy without hysterectomy | 1 |

| Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with hysterectomy | 6 |

| NG | 12 |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 14 |

| No | 18 |

| Survival time > 2 yr | 4 |

Metastatic ovarian cancers secondary to gastrointestinal cancer are called Krukenberg tumors; an ovarian metastasis from PC presenting as a Krukenberg tumor is rare[7,13]. Ovarian tumors usually dominate the clinical presentation[3]. Ovarian metastases commonly originate from malignant tumors of the stomach, breast, colorectum, appendix, and cervix. However, metastases from PC to the ovaries are rare[3,10,14-16]. PC as the primary cancer accounted for an estimated 7% of cases of non-genital ovarian metastasis[4,7]. Among these cases, patient age ranged from 24 to 83 years. The major complaints were abdominal pain and abdominal masses. In some case reports, there was a lack of description of symptoms. We deduced that some of the abnormalities might have been discovered incidentally during physical examinations.

PCs that initially present as ovarian metastases are very difficult to diagnose. In many cases, patients were diagnosed with ovarian neoplasms with lower abdominal symptoms, which would distract from an accurate examination by doctors. Twenty-one patients in our review were classified to have an ovarian tumor at the initial presentation. Only five patients were diagnosed with a primary pancreatic mass at the initial hospital admission. In almost 50% of cases, PC and ovarian metastases were found simultaneously. Many patients were first admitted into the gynecology department, were prepared to undergo a gynecological operation, and were then diagnosed with primary PC during the preoperative examination or intraoperative exploration. Currently, the combination between gynecology and general Surgery departments is important. Surgery should be contemplated only after multidisciplinary discussion.

Clinically, doctors might tend to pay attention only to pancreatic neoplasms or ovarian lesions. Without enhanced CT of the whole abdomen and pelvis, this tendency can often lead to misdiagnosis. Positron-emission tomography-CT remains the best method for identifying metastatic lesions, but it is expensive and not included in routine examinations. Currently, serum biomarkers are highly valuable. CA 19-9 is commonly used to identify PC. Unfortunately, most of the published reports lacked data on biomarkers. Another effective diagnostic method is endoscopic ultrasonography, which was applied to clinical practice three decades ago[17]. And endoscopic ultrasonography plus fine-needle aspiration was introduced to distinguish primary from metastatic tumors although with a suboptimal accuracy[18]. In our case, the ultrasound-guided biopsy exerted an important role in pre-operative diagnosis. Nowadays, the value of endoscopic ultrasonography for the differential diagnosis of various pancreatic lesions (malignant, low-grade malignant, and benign) has been widely depicted[18-21].

The primary tumor was mostly located in the body and tail of the pancreas (20 cases in our review). The metastatic path of PC to the ovary is similar to that for the Krukenberg tumor[22] and is closely correlated with lymphatic metastasis. For infiltrative tumors in the body or tail of the pancreas, cells enter the lymphatic reflux system of the retroperitoneum. These cancer cells can cause mechanical blockage of the lower abdominal lymphatic vessels, resulting in retrograde lymphatic flow. The cancer cells can migrate to the pelvic lymph nodes, resulting in ovarian metastases[23]. In addition, tumors invading the pancreatic capsule could also fall into the pelvic cavity. Furthermore, PCs metastasizing to the ovaries often lead to bilateral ovarian metastases; microscopic examination sometimes reveals cancer emboli in lymphatic vessels[23-26].

The optimal treatment for PC with ovarian metastases is complete resection of lesions. Even with unresectable PC, resection of the ovarian metastasis is still necessary since it can effectively relieve the clinical symptoms. After palliative resection of the ovarian metastasis, some patients can achieve a relatively satisfying chemotherapeutic effect[9]. Among the 32 patients, 20 underwent salpingo-oophorectomy and 6 underwent hysterectomy. However, only five patients had the opportunity to undergo pancreatectomy. It is unclear whether resection of the primary lesion can prolong survival; currently, no reliable indicators are available, and thus, this requires further investigation. In addition, only 14 patients received chemotherapy. Postoperative chemotherapy is generally considered to improve prognosis. However, the prognosis could not be predicted in most cases. Our patient died 3.5 mo after the operation; thus far, only four patients have survived for > 2 years, as reported by Marco et al[11] and Falchook et al[9].

Most of the cases involved ductal adenocarcinoma, and eight cases involved mucinous adenocarcinoma, which is partially similar to the finding reported by Petru et al[27]. Patients were misdiagnosed with primary ovarian mucinous carcinomas by many pathologists, because PC can produce large metastatic, multicystic, ovarian tumors that appear similar to primary ovarian mucinous neoplasms[3]. Ovarian metastases are characterized by multiple cysts containing mucoid material and an external surface lobulated with small gray to yellow nodules. Usually, less than 3% of primary ovarian carcinomas are mucinous, and most of those are unilateral and present as stage I disease at diagnosis.

Our review also shows that 20 cases involved bilateral ovarian metastases. If the ovarian lesion is of the mucinous type, this may suggest that it originates from a non-ovarian primary tumor[28,29]. In addition to morphological features, immu-nohistochemical staining may help distinguish primary ovarian cancers and metastatic ovarian tumors[22,30-33]. Many pancreatic and ovarian carcinomas are positive for CK7 and show variable expression of CK20[34,35]. It was also reported that the combination of MUC5ac positivity/WT-1 negativity was seen in PC, whereas the combination of MUC5ac negativity/WT-1 positivity was seen in ovarian carcinoma[36]. However, no immunohistochemical marker alone can be used to specifically differentiate primary ovarian neoplasms from metastatic ovarian mucinous neoplasms; no reliable diagnostic criteria have yet been established. With the advances in the fields of genomics and proteomics, we hope that the molecular profiling of PC and ovarian metastases can reveal the underlying molecular mechanisms and identify reliable diagnostic biomarkers.

In clinical practice, PCs with ovarian metastases are rare and difficult to diagnose; surgical opportunities tend to be missed in these patients. They are easily misdiagnosed as primary ovarian carcinomas. The resection of any metastases from PC is strongly recommended.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fusaroli P S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9-29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Maitra A, Hruban RH. Pancreatic cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:157-188. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Hart WR. Diagnostic challenge of secondary (metastatic) ovarian tumors simulating primary endometrioid and mucinous neoplasms. Pathol Int. 2005;55:231-243. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Young RH, Hart WR. Metastases from carcinomas of the pancreas simulating primary mucinous tumors of the ovary. A report of seven cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:748-756. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Niwa K, Yoshimi N, Sugie S, Sakamoto H, Tanaka T, Kato K, Kaneko H, Mori H. A case of double cancer (pancreatic and ovarian adenocarcinomas) diagnosed by exfoliative and fine needle aspiration cytology. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1988;18:167-173. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Fujiwara K, Ohishi Y, Koike H, Sawada S, Moriya T, Kohno I. Clinical implications of metastases to the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;59:124-128. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Moore RG, Chung M, Granai CO, Gajewski W, Steinhoff MM. Incidence of metastasis to the ovaries from nongenital tract primary tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:87-91. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Yazigi R, Sandstad J. Ovarian involvement in extragenital cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;34:84-87. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Falchook GS, Wolff RA, Varadhachary GR. Clinicopathologic features and treatment strategies for patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and ovarian metastases. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:515-519. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Vakiani E, Young RH, Carcangiu ML, Klimstra DS. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas metastatic to the ovary: a report of 4 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1540-1545. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Di Marco M, Vecchiarelli S, Macchini M, Pezzilli R, Santini D, Casadei R, Calculli L, Sina S, Panzacchi R, Ricci C, Grassi E, Minni F, Biasco G. Preoperative gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in a patient with ovarian metastasis from pancreatic cystadenocarcinoma. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:530-537. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Nomoto D, Hashimoto D, Motohara T, Chikamoto A, Nitta H, Beppu T, Katabuchi H, Baba H. EDUCATION AND IMAGING. Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic: Rapid growing cystic ovarian metastasis from pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:707. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Kiyokawa T, Young RH, Scully RE. Krukenberg tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 120 cases with emphasis on their variable pathologic manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:277-299. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Baker PM, Oliva E. Immunohistochemistry as a tool in the differential diagnosis of ovarian tumors: an update. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2005;24:39-55. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Shi Y, Ye D, Lu W, Zhao C, Xu J, Chen L. [Histological classification in 10 288 cases of ovarian malignant tumors in China]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2002;37:97-100. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Ayhan A, Guvenal T, Salman MC, Ozyuncu O, Sakinci M, Basaran M. The role of cytoreductive surgery in nongenital cancers metastatic to the ovaries. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;98:235-241. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Fusaroli P, Kypraios D, Eloubeidi MA, Caletti G. Levels of evidence in endoscopic ultrasonography: a systematic review. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:602-609. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Fusaroli P, D'Ercole MC, De Giorgio R, Serrani M, Caletti G. Contrast harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography in the characterization of pancreatic metastases (with video). Pancreas. 2014;43:584-587. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Arya N, Wyse JM, Jayaraman S, Ball CG, Lam E, Paquin SC, Lightfoot P, Sahai AV. A proposal for the ideal algorithm for the diagnosis, staging, and treatment of pancreas masses suspicious for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Results of a working group of the Canadian Society for Endoscopic Ultrasound. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9:154-161. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Moris M, Raimondo M, Woodward TA, Skinner VJ, Arcidiacono PG, Petrone MC, De Angelis C, Manfrè S, Carrara S, Jovani M, Fusaroli P, Wallace MB. International Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms Registry: Long-Term Results Based on the New Guidelines. Pancreas. 2017;46:306-310. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Ishigaki K, Nakai Y, Oyama H, Kanai S, Suzuki T, Nakamura T, Sato T, Hakuta R, Saito K, Saito T, Takahara N, Hamada T, Mizuno S, Kogure H, Tada M, Isayama H, Koike K. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Tissue Acquisition by 22-Gauge Franseen and Standard Needles for Solid Pancreatic Lesions. Gut Liver. 2020. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Young RH. From krukenberg to today: the ever present problems posed by metastatic tumors in the ovary: part I. Historical perspective, general principles, mucinous tumors including the krukenberg tumor. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:205-227. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Takenoue T, Yamada Y, Miyagawa S, Akiyama Y, Nagawa H. Krukenberg tumor from gastric mucosal carcinoma without lymphatic or venous invasion: report of a case. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1211-1214. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Shiomi M, Kamisako T, Yutani I, Kudo M, Shigeoka H, Tanaka A, Okuno K, Yasutomi M. Two cases of histopathologically advanced (stage IV) early gastric cancers. Tumori. 2001;87:191-195. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Jain V, Gupta K, Kudva R, Rodrigues GS. A case of ovarian metastasis of gall bladder carcinoma simulating primary ovarian neoplasm: diagnostic pitfalls and review of literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16 Suppl 1:319-321. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Sakakura C, Hagiwara A, Yamazaki J, Takagi T, Hosokawa K, Shimomura K, Kin S, Nakase Y, Fukuda K, Yamagishi H. Management of postoperative follow-up and surgical treatment for Krukenberg tumor from colorectal cancers. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1350-1353. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Petru E, Pickel H, Heydarfadai M, Lahousen M, Haas J, Schaider H, Tamussino K. Nongenital cancers metastatic to the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;44:83-86. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | McCluggage WG, Wilkinson N. Metastatic neoplasms involving the ovary: a review with an emphasis on morphological and immunohistochemical features. Histopathology. 2005;47:231-247. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Seidman JD, Horkayne-Szakaly I, Haiba M, Boice CR, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM. The histologic type and stage distribution of ovarian carcinomas of surface epithelial origin. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004;23:41-44. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Lee KR, Young RH. The distinction between primary and metastatic mucinous carcinomas of the ovary: gross and histologic findings in 50 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:281-292. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Vang R, Gown AM, Barry TS, Wheeler DT, Ronnett BM. Immunohistochemistry for estrogen and progesterone receptors in the distinction of primary and metastatic mucinous tumors in the ovary: an analysis of 124 cases. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:97-105. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Dionigi A, Facco C, Tibiletti MG, Bernasconi B, Riva C, Capella C. Ovarian metastases from colorectal carcinoma. Clinicopathologic profile, immunophenotype, and karyotype analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114:111-122. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Goldstein NS, Bassi D, Uzieblo A. WT1 is an integral component of an antibody panel to distinguish pancreaticobiliary and some ovarian epithelial neoplasms. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;116:246-252. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Lee BH, Hecht JL, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS. WT1, estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor as markers for breast or ovarian primary sites in metastatic adenocarcinoma to body fluids. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:745-750. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Giorgadze TA, Peterman H, Baloch ZW, Furth EE, Pasha T, Shiina N, Zhang PJ, Gupta PK. Diagnostic utility of mucin profile in fine-needle aspiration specimens of the pancreas: an immunohistochemical study with surgical pathology correlation. Cancer. 2006;108:186-197. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Han L, Pansare V, Al-Abbadi M, Husain M, Feng J. Combination of MUC5ac and WT-1 immunohistochemistry is useful in distinguishing pancreatic ductal carcinoma from ovarian serous carcinoma in effusion cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:333-336. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |