Published online Jan 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i2.242

Peer-review started: September 24, 2018

First decision: October 25, 2018

Revised: November 23, 2018

Accepted: December 7, 2018

Article in press: December 8, 2018

Published online: January 26, 2019

Collision carcinoma is rare in clinical practice, especially in the head and neck region. In this paper, we report a case of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) colliding in the larynx and review 12 cases of collision carcinoma in the head and neck to further understand collision carcinoma, including its definition, diagnosis, and treatment.

A 61-year-old man presented with a 1-year history of hoarseness. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the larynx revealed that the right vocal cord had a nodule-like thickening with obvious enhancement. Laryngoscopy revealed a neoplasm on the right vocal cord, and a malignant tumor was initially considered. A frozen section of right vocal cord was performed under general anesthesia. The pathological result showed a malignant tumor in the right vocal cord. The tumor was excised with a CO2 laser (Vc type). Routine postoperative pathology showed moderately differentiated SCC with small cell NEC in the right vocal cord. No metastatic lymph nodes or distant metastases were found on postoperative positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Because of the coexistence of SCC and NEC, the patient received adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The patient was followed for 8 mo, and no recurrence or distant metastasis was found.

The treatment of collision carcinoma in the head and neck region is uncertain due to the small number of cases.

Core tip: Collision carcinoma is rare in clinical practice, especially in the head and neck region. In this paper, we report a case of squamous cell carcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma colliding in the larynx and review 12 cases of collision carcinoma in the head and neck to further understand collision carcinoma, including its definition, diagnosis, and treatment.

- Citation: Yu Q, Chen YL, Zhou SH, Chen Z, Bao YY, Yang HJ, Yao HT, Ruan LX. Collision carcinoma of squamous cell carcinoma and small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(2): 242-252

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i2/242.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i2.242

The term “collision carcinoma” refers to two malignant tumors coexisting in the same organ but having different histological morphologies[1]. The two components of a collision carcinoma originate from the same organ and have no transition area between them[2]. Fujii et al[3] proposed some theoretical hypotheses about the origin of collision carcinoma according to genetic patterns as follows: (1) collision carcinoma develops from two separate tumor clonal cells; (2) there are two genetic phenotypes for tumor clonal cells with homogenous genes, representing completely different tumor types with two histological differentiation potentials; and (3) during the process of development of the same tumor clonal cells, genetic heterogeneity enables the tumor cells to develop into two parallel histologic manifestations, a mechanism closely related to the assembly of subcloned tumor cells. However, no consensus has been reached about the actual mechanism. Collision carcinoma is rare in clinical practice, and reported cases have been primarily in the esophagus, cervix, breast, and bladder. Collision carcinoma in the head and neck region is uncommon and mostly occurs in the thyroid gland, and less so in the larynx[4]. No coexistence of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) in the larynx was observed in previously reported cases. At present, it is generally believed that the treatment for collision carcinoma should be based on the more invasive or malignant histological component of the carcinoma[5]. Because of its low frequency and individuality, there is still no clear clinical understanding of collision carcinoma, and controversy over its definition, diagnosis, and treatment still exists.

We report a case of SCC and NEC colliding in the right vocal cord to further the understanding of collision carcinoma.

A 61-year-old man presented with the chief complaint of a 1-year history of hoarseness.

The hoarseness with discomfort in the throat was aggravated after excessive use of the sound. The patient had no fever, chest tightness, shortness of breath, or difficulty swallowing.

The patient used to have a good physical condition and no history of major past illnesses. He had smoked a pack of cigarettes and drunk 500 mL of non-distilled wine per day for 30 years.

There were no similar patients in the family.

Indirect laryngoscopy prompted a neoplasm in the right vocal cord. The vocal cords had great activity and closure.

No obvious abnormalities were found in laboratory examinations.

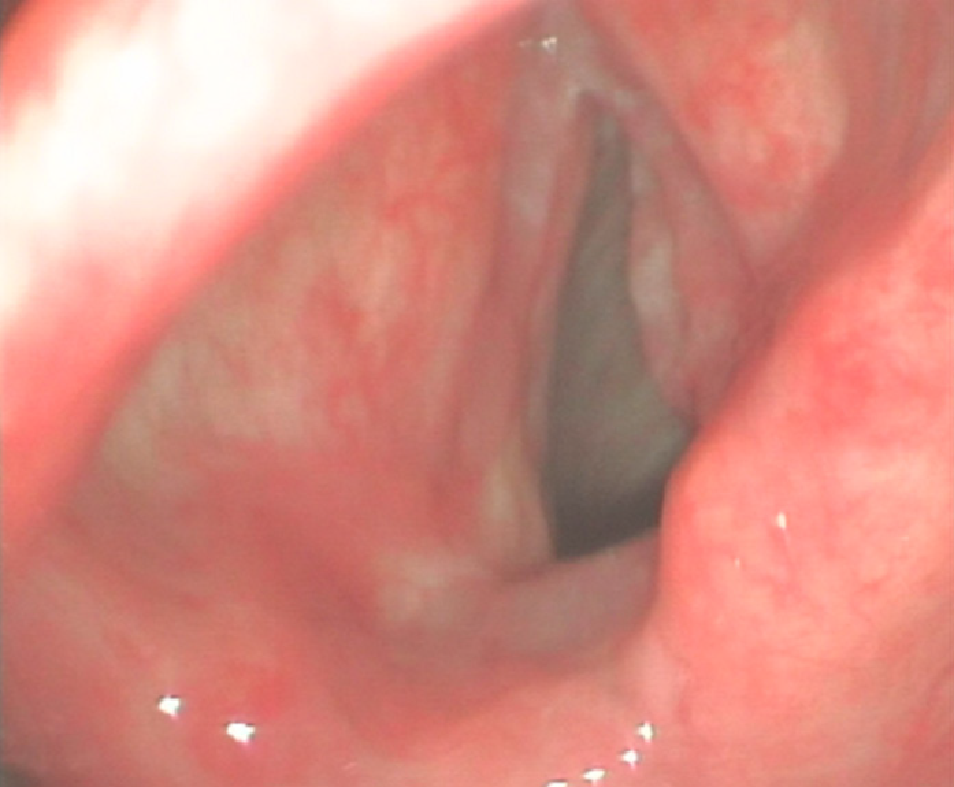

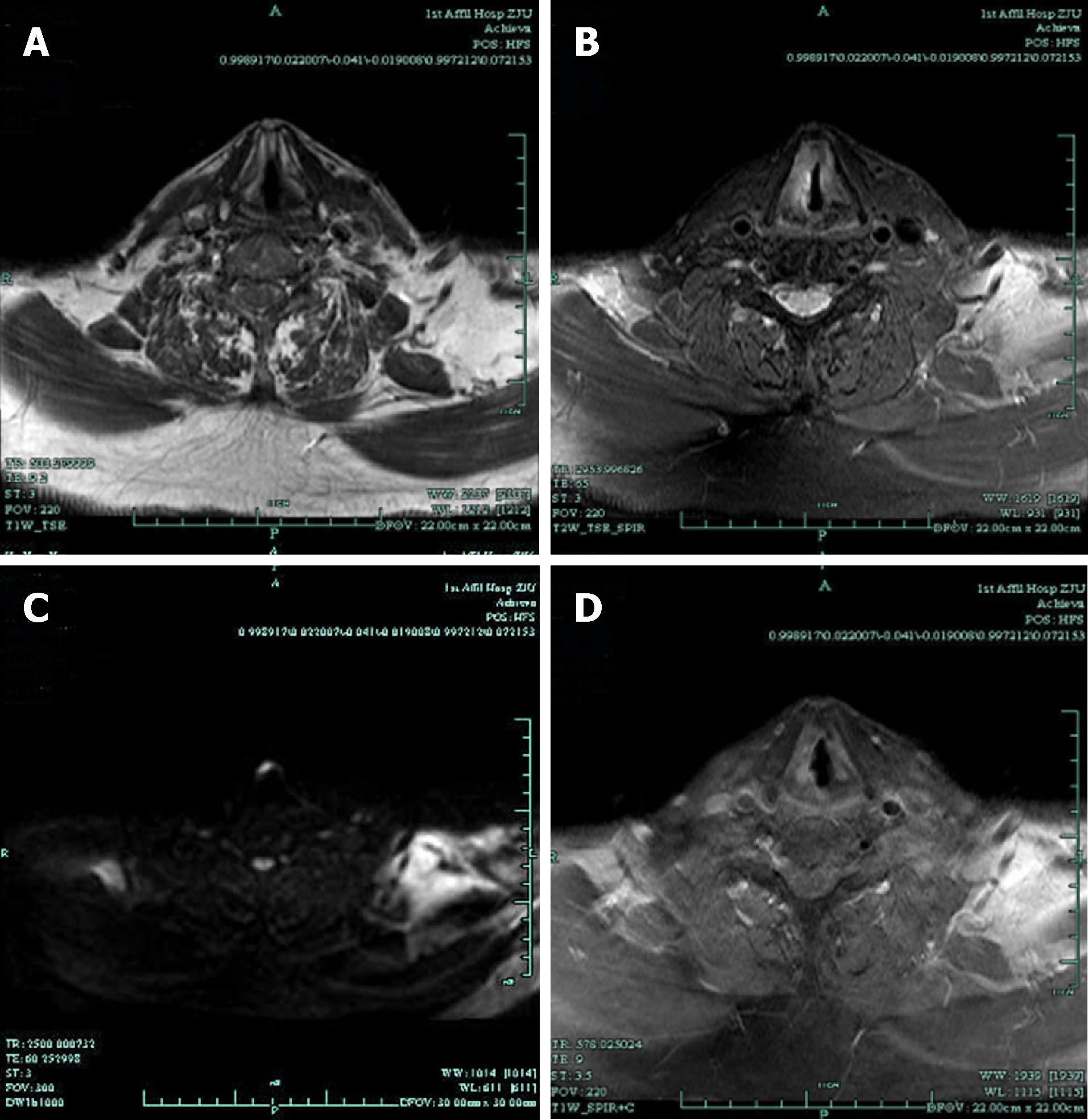

Direct laryngoscopy revealed a pink neoplasm on the anterior two-thirds of the right true vocal cord (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast revealed the right vocal cord was thicker than the left. T1-weighted imaging was isointense, T2-weighted imaging was hyperintense, and diffusion-weighted imaging was hyperintense; gadopentetic acid (Gd-DTPA) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images were obviously enhanced (Figure 2). The patient underwent transoral surgery with a CO2 laser under general anesthesia. Under a microscope, a light red neoplasm with a rough surface was seen in the right vocal cord, laryngeal ventricle, anterior commissure, and anterior one-third of the left vocal cord. A biopsy was performed on the right vocal cord. The frozen section showed that the neoplasm in the right vocal cord was a malignant tumor that should be cleared according to the results of routine postoperative pathology and immunohistochemistry.

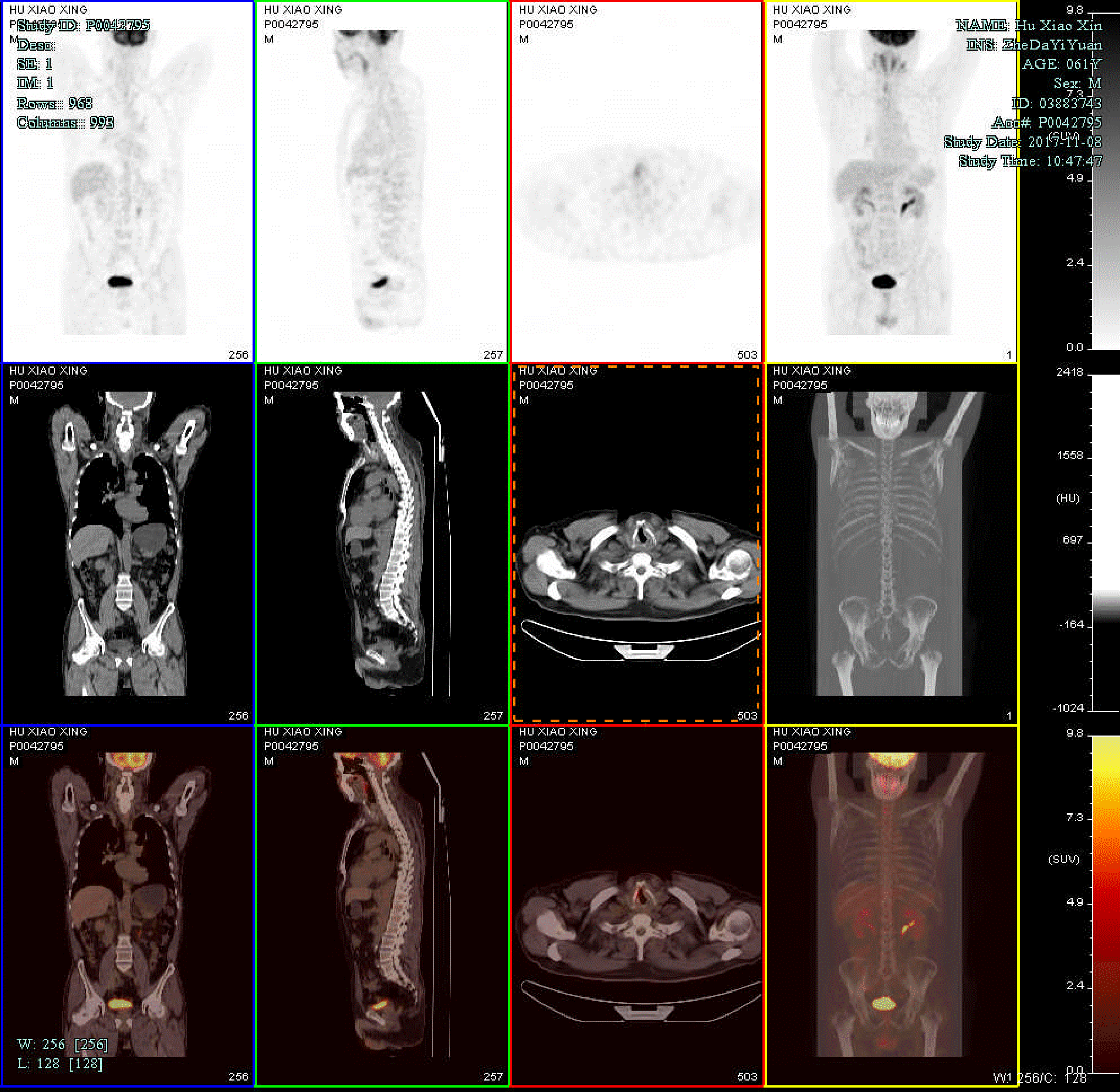

Routine postoperative pathology showed the coexistence of SCC and NEC cells (Figure 3). On immunohistochemical staining, the tumor cells were positive for synaptophysin, cytokeratin, CD56, and P63, and negative for chromogranin A. The Ki 67 index was up to 90% (Figure 4). These features supported a diagnosis of collision carcinoma [moderately differentiated SCC and small cell NEC (SCNEC) in the right vocal cord]. Postoperative positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) showed high-level uptake of (18F)-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) in the right vocal cord [maximum standardized uptake (SUVmax) = 5.6], and no high FDG lesions in other parts of the body (Figure 5). The clinical stage was classified as stage (T1bN0M0 involving the anterior commissure).

The tumor was excised with a transoral CO2 laser (Vc type) according to European endoscopic cordectomy classification criteria. However, the lateral and anterior section margins were positive after two excisions. Thus, further treatment was performed according to the final pathological diagnosis. The patient received concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy (RT). Four cycles of etoposide 170 mg and carboplatin 570 mg (once every 3 wk) were given. Laryngeal targeted radiation therapy followed, and the radiation dose was 2 Gy × 28 F, totaling 56 Gy.

The patient was followed for 13 mo and no recurrence or distant metastasis was noted.

The definition of collision carcinoma is controversial, with different researchers having different interpretations. Some believe that collision carcinoma can occur in adjacent organs, and that the tumors can eventually invade each other[6-8]. Kufeld et al[6] reported a case of collision carcinoma of hypopharyngeal adenoid cystic carcinoma and laryngeal SCC. Marangoni et al[7] reported carcinomas colliding in the aryepiglottic fold of hypopharyngeal SCC and laryngeal NEC. Jacobson et al[8] reported a case of papillary thyroid carcinoma and laryngeal SCC. They suggested that this was a case of collision carcinoma[6-8]. Some researchers have posited that a benign tumor and a malignant tumor, or two benign tumors, occurring in one organ at the same time can also be considered as collision carcinoma[9]. Chau et al[9] reported a case of collision carcinoma of laryngeal pleomorphic adenoma and laryngeal SCC. They expanded the definition of collision carcinoma to include benign tumors. Furthermore, others claim that collision carcinoma can occur in the same place as a primary tumor and a metastasis[10,11]. Kakarala et al[10] reported collision carcinoma of cervical lymph node metastatic SCC and B-cell lymphoma. Brandwein-Gensler et al[11] reported collision carcinoma in the thyroid (metastatic liposarcoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma). We suggest the following: collision carcinoma should be considered only when there are two malignant tumors that look like a mass to the naked eye and originate from the same organ, but are of different pathological types and with neither tumor having migrated to the other[2,12]. Organs in the head and neck region are adjacent to each other; thus it is easy to misidentify tumors that originate from different organs and eventually invade each other at the same location as collision carcinoma[6-8]. We prefer to call these tumors multiple primary carcinomas[13]. Koutsopoulos et al[13] reported a case having a combination of multiple primary carcinomas: urinary bladder transitional cell carcinoma, metachronous prostate adenocarcinoma, and small cell lung carcinoma. It is also important to distinguish between collision carcinoma and mixed carcinoma. Mixed carcinoma shows the combined histopathological characteristics of two or more previously recognized tumors and/or cysts of different types[14]. Two constituent parts are mixed together and obvious histological transition is often observed[14]. Koliouskas et al[14] reported a mixed carcinoma comprising hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Thus, the present case is a good example of collision carcinoma because: (1) two different pathological types of tumors, both malignant, were involved; (2) both malignant tumors originated from the right vocal cord; and (3) the two tumors were independent and there was no migration between them. In efforts to explain the origins of the two components of collision carcinoma, two principal histogenetic theories have been proposed: simultaneous proliferation of multiple cell lineages or differentiation of stem/progenitor cells into multiple cell lineages[15]. Scardoni et al[15] performed next-generation sequencing of adenoneuroendocrine carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract and showed that the two different components shared similar molecular profiles, supporting the idea that they originated from a common progenitor cell. This may be true of both collision and mixed tumors[15]. Although no next-generation sequencing data for collision carcinomas of the head and neck region are available, it is likely that the two tumor components share a common genetic origin.

The incidence of collision carcinoma is very low, and that of collision carcinoma occurring in the head and neck even lower. Most head and neck collision carcinomas occur in the thyroid, with only a few being seen in the larynx[4]. Based on our definition of collision carcinoma, we found a total of 12 cases in the English-language literature from 2000 to 2018 (key words: collision carcinoma, head and neck; or collision tumor, head and neck)[1,2,5,16-24]. Of these recent cases, seven were male and five were female. The male-to-female ratio was thus approximately 1.4:1, with no significant difference in prevalence between genders. The mean age of the 12 patients was 61 years (range: 32-88 years). Their clinical pathological features, treatments, and outcomes are summarized in Table 1. In eight (66.6%) cases[1,2,16,18-20,22,23], only one carcinoma was detected during the preoperative biopsy. Two cases[5,24] did not undergo a preoperative biopsy or had a failed biopsy. In only two (16.7%) of the 12 cases, the two components were successfully detected during the preoperative biopsy[17,21]. Thus, it is clear that accurate preoperative diagnosis of collision carcinoma is very difficult, and it is hard to acquire two kinds of tissue components at the same time by biopsy, which presents certain obstacles to the choice of treatment. Most previous cases were treated by surgery. After the routine postoperative pathology was clearly defined, adjuvant treatment was added. Only two cases, in which the two components of the tumor were identified, were treated by RT alone, which avoided the adverse effects associated with blindly choosing surgical treatment. Therefore, improving the accuracy of biopsy and accurately diagnosing collision carcinoma before surgery are of great importance. Biopsy data should be evaluated in combination with the clinical history and imaging information. If the histopathological diagnosis does not reflect the clinical features of the lesion, the biopsy data should be questioned. The accuracy of biopsy data can be increased to maximize the probability of identifying multiple lesions by: (1) photography prior to intervention; (2) data evaluation by several clinicians; and (3) performing a large incisional biopsy[25]. In addition to biopsy, it is also crucial to confirm that the components of the collision carcinoma are not metastases from primary sites in other parts of the body[26].

| Ref. | Year | Sex/age | Presentation | Location | Histology | Biopsy result | Treatment | Follow-up |

| Sirikanjanapong et al[1] | 2010 | M/53 | Hoarseness | Larynx | Melanoma/SCC | Melanoma | Surgery + RT | Alive |

| Medina-Banegas et al[16] | 2003 | M/45 | Dyspnea | Larynx | CHS/epidermoidcarcinoma | CHS | Surgery | Alive |

| Karasmanis et al[17] | 2013 | M/53 | None | Larynx | ACC/AC | ACC/AC | RT | NA |

| Udompatanakorn et al[18] | 2018 | M/59 | A painful mass | Soft Palate | NEC/SCC | SCC | Surgery | Alive |

| Franchi et al[19] | 2013 | M/75 | Acute ischemic stroke | Maxillary Sinus | NEC/SCC | SCC | Surgery + RT | Alive |

| Huang et al[20] | 2010 | F/52 | Left cheek swelling and purulent mucoid nasal discharge | Maxillary Sinus | ASC/NEC | NEC | Surgery + Chemotherapy | Dead |

| Du et al[21] | 2015 | M/63 | Nasal obstruction and epistaxis | Nasopharynx | EMP/NPC | EMP/NPC | RT | Alive |

| Sadat Alavi et al[22] | 2011 | M/32 | Anterior neck mass | Thyroid | MTC/PTC | PTC | Surgery + I131 + ST | Alive |

| Walvekar et al[23] | 2006 | F/65 | Thyroid swelling | Thyroid | PTC/SCC | PTC | Surgery + I131 | No follow-up |

| Warman et al[24] | 2011 | F/84 | Right neck mass and dysphagia | Thyroid | SCC/PTC | none | Surgery + RT | dead |

| Plauche et al[2] | 2012 | F/62 | A thyroid mass and shortness of breath | Thyroid | PTC/FTC | FTC | Surgery + I131 | NA |

| Ryan et al[5] | 2014 | F/88 | Inspiratory stridor and airway distress | Thyroid | PTC/SCC | none | Surgery + I131 | NA |

As far as we know, there have been no previous reports of a laryngeal SCC colliding with a laryngeal NEC. Thus, this is the first report on collision carcinoma involving SCC and NEC in the same vocal cord. It is generally believed that the treatment for collision carcinoma should be based on the more invasive or malignant histology of the two carcinomas[5]. In the present case, the degree of malignancy of NEC was higher, and thus informed the treatment. NEC is a kind of malignant tumor with endocrine function[27]. It is now thought that tumor cells with neuroendocrine characterization may secrete peptides through autocrine or paracrine mechanisms to stimulate tumor growth[27]. NEC is common in the lungs[28]. The most common site outside of the lungs is the esophagus, and the most common site in the head and neck region is the larynx[28]. Although NEC is relatively uncommon in the larynx, accurate identification of subtypes by immunohistochemistry has major implications for treatment, because each subtype has its own characteristics and treatment modality. In 2005, the World Health Organization classified NEC into three subtypes: well-differentiated (typical carcinoid), moderately differentiated (atypical carcinoid), and poorly differentiated (large and small cell carcinoma)[29]. Atypical carcinoid is the most common laryngeal NEC; it is usually located in the supraglottic area and is often invasive[29]. It easily metastasizes to lymph nodes, and can also distantly metastasize to the lung, liver, pancreas, prostate, and breast[29]. The recommended treatment for this subtype is local extended resection + bilateral lymph node dissection + postoperative adjuvant therapy[29]. In one study, the cumulative proportion of atypical carcinoid that survived was 48% at 5 years and 30% at 10 years[30]. Typical carcinoid also mostly occurs in the supraglottic area, but metastasis is rarely seen[29,30]. Therefore, surgical resection can achieve good results. In addition, typical carcinoid is not sensitive to RT or chemotherapy, so postoperative radiochemotherapy is not required[29,31,32]. Our case was of the small cell type, which has the highest degree of malignancy and a poor prognosis[29]. It has been reported that the 2- and 5-year survival rates of SCNEC are 16% and 5%, respectively[33]. SCNEC has a rapid growth rate and high metastatic potential; approximately 50% of patients have positive regional lymph nodes and more than two-thirds present with distant metastases, most frequently to cervical lymph nodes, liver, lungs, bones, and bone marrow[6,28,34]. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines of Neuroendocrine Tumors (ver. 1.2015), poorly differentiated (large and small cell carcinoma) patients can be divided into three treatment groups according to their general condition, as evaluated by chest/abdominal/pelvic CT with contrast, brain MRI/CT with contrast, or PET/CT scan: (1) the recommended treatment for resectable tumors is resection + chemotherapy ± RT or consider definitive chemoradiation; (2) the recommended treatment for locoregional unresectable tumors is RT + chemotherapy; and (3) the recommended treatment for tumors with distant metastasis is chemotherapy alone[35]. However, in the majority of reported cases of SCNEC, radical surgical procedures (including total laryngectomy and radical neck dissection) have not achieved good results[36]. Furthermore, laryngectomy greatly affects patients’ quality of life[31]. It is generally believed that surgical treatment is not the first choice for SCNEC, although laryngectomy can control the progression of primary laryngeal carcinomas to some extent[31]. Ferlito et al[31] proposed that surgery alone or in combination with radiation cannot improve local tumor control, and thus chemotherapy is a better choice. Adjuvant chemotherapy is the most accepted and effective treatment and can extend patients’ median survival time from 11 to 19 mo[31]. The combination of primary RT and adjuvant chemotherapy can achieve a median survival of 55 mo, which is significantly longer than that with any other treatment[31]. RT alone can only control tumor progression in the primary site, with no improvement in patient survival time[31]. However, prophylactic cranial irradiation has been suggested as part of the management for SCNEC, because the chemotherapeutic agents commonly used cannot penetrate the blood-brain barrier[31]. At present, a combination of RT and chemotherapy is recommended for SCNEC, where the strategy is essentially the same as that for treatment of small cell lung cancer[37]. Head and neck non-sinonasal NEC is sensitive to etoposide and cisplatin, and the suggested treatment period is 9 to 18 mo[28,31]. In general, the prognosis of SCNEC is poor due to invasiveness and resistance to chemotherapy and RT[31].

Due to the scarcity, contingency, and complexity of collision carcinoma, the treatments are significantly more complicated than those for conventional carcinoma, and are more closely related to the pathological components, site of onset, and presence or absence of distant metastases.

In summary, we report a case of laryngeal collision carcinoma of SCC and SCNEC. Collision carcinoma in the head and neck region is rare, especially in the larynx. We have explored the definition, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of collision carcinoma to further understand this disease, but much remains to be learned. Each collision carcinoma has its own contingency and individual characteristics, and more case reports and studies are needed.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chen YK, Luchini C S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Sirikanjanapong S, Lanson B, Amin M, Martiniuk F, Kamino H, Wang BY. Collision tumor of primary laryngeal mucosal melanoma and invasive squamous cell carcinoma with IL-17A and CD70 gene over-expression. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4:295-299. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Plauche V, Dewenter T, Walvekar RR. Follicular and papillary carcinoma: a thyroid collision tumor. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;65:182-184. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Fujii H, Zhu XG, Matsumoto T, Inagaki M, Tokusashi Y, Miyokawa N, Fukusato T, Uekusa T, Takagaki T, Kadowaki N, Shirai T. Genetic classification of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1011-1017. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Coca-Pelaz A, Triantafyllou A, Devaney KO, Rinaldo A, Takes RP, Ferlito A. Collision tumors of the larynx: A critical review. Am J Otolaryngol. 2016;37:365-368. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Ryan N, Walkden G, Lazic D, Tierney P. Collision tumors of the thyroid: A case report and review of the literature. Head Neck. 2015;37:E125-E129. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Kufeld M, Junker K, Sudhoff H, Dazert S. [Collision tumor of a hypopharyngeal adenoidcystic carcinoma and a laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma]. Laryngorhinootologie. 2004;83:51-54. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Marangoni R, Mauramati S, Bertino G, Occhini A, Benazzo M, Morbini P. Hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma and laryngeal neuroendocrine carcinoma colliding in the aryepiglottic fold: a case report. Tumori. 2017;103:e1-e4. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Jacobson AS, Wenig BM, Urken ML. Collision tumor of the thyroid and larynx: a patient with papillary thyroid carcinoma colliding with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Thyroid. 2008;18:1325-1328. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Chau JK, Girgis S, Chau JK, Seikaly HR, Harris JR. Laryngeal collision tumour: pleomorphic adenoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;38:E31-E34. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Kakarala K, Sadow PM, Emerick KS. Cervical lymph node collision tumor consisting of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma and B-cell lymphoma. Laryngoscope. 2010;120 Suppl 4:S156. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Brandwein-Gensler M, Urken M, Wang B. Collision tumor of the thyroid: a case report of metastatic liposarcoma plus papillary thyroid carcinoma. Head Neck. 2004;26:637-641. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Yang L, Sun X, Zou Y, Meng X. Small cell type neuroendocrine carcinoma colliding with squamous cell carcinoma at esophagus. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:1792-1795. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Koutsopoulos AV, Dambaki KI, Datseris G, Giannikaki E, Froudarakis M, Stathopoulos E. A novel combination of multiple primary carcinomas: urinary bladder transitional cell carcinoma, prostate adenocarcinoma and small cell lung carcinoma--report of a case and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:51. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Koliouskas D, Patsiaoura K, Eleftheriadis N, Lazaraki G, Sidiropoulos J, Ziakas A. A case of Mixed Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Cholangiocarcinoma in a 27-year-old female patient with ulcerative colitis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2001;14. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Scardoni M, Vittoria E, Volante M, Rusev B, Bersani S, Mafficini A, Gottardi M, Giandomenico V, Malleo G, Butturini G, Cingarlini S, Fassan M, Scarpa A. Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract: targeted next-generation sequencing suggests a monoclonal origin of the two components. Neuroendocrinology. 2014;100:310-316. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Medina-Banegas A, Osete-Albaladejo JM, Capitán-Guarnizo A, López-Meseguer E, Pastor-Quirante F. Double tumor of the larynx: a case report. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;260:341-343. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Karasmanis I, Goudakos JK, Vital I, Zarampoukas T, Vital V, Markou K. Hybrid carcinoma of the larynx: a case report (adenoid cystic and adenocarcinoma) and review of the literature. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2013;2013:385405. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Udompatanakorn C, Yada1 N, Ishikawa A, Miyamoto I, Sato Y, Matsuo K. Primary Neuroendocrine Carcinoma Combined with Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Soft Palate: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Open J Stomatol. 2018;8:90-99 [doi:10.4236/ojst.2018.83008]. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Franchi A, Rocchetta D, Palomba A, Degli Innocenti DR, Castiglione F, Spinelli G. Primary combined neuroendocrine and squamous cell carcinoma of the maxillary sinus: report of a case with immunohistochemical and molecular characterization. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:107-113. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Huang SF, Chuang WY, Cheng SD, Hsin LJ, Lee LY, Kao HK. A colliding maxillary sinus cancer of adenosquamous carcinoma and small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma--a case report with EGFR copy number analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:92. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Du RC, Li HN, Huang W, Tian XY, Li Z. Unusual coexistence of extramedullary plasmacytoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma in nasopharynx. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:170. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Sadat Alavi M, Azarpira N. Medullary and papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland occurring as a collision tumor with lymph node metastasis: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:590. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Walvekar RR, Kane SV, D'Cruz AK. Collision tumor of the thyroid: follicular variant of papillary carcinoma and squamous carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:65. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Warman M, Lipschitz N, Ikher S, Halperin D. Collision tumor of the thyroid gland: primary squamous cell and papillary thyroid carcinoma. ISRN Otolaryngol. 2011;2011:582374. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Shams PN, Olver JM. A case of cutaneous collision tumour: the importance of photographic documentation and large incisional biopsy. Eye (Lond). 2006;20:1324-1325. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Jaiswal VR, Hoang MP. Primary combined squamous and small cell carcinoma of the larynx: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1279-1282. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Yamagata K, Terada K, Uchida F, Kanno N, Hasegawa S, Yanagawa T, Bukawa H. A Case of Primary Combined Squamous Cell Carcinoma with Neuroendocrine (Atypical Carcinoid) Tumor in the Floor of the Mouth. Case Rep Dent. 2016;2016:7532805. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Ozdogan F, Ozcan KM, Ikinciogullari A, Ozdas T, Dere H. Small Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Larynx: A Case Report and Literature Review. J Clin Anal Med. 2016;7:271-274. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Ghosh R, Dutta R, Dubal PM, Park RC, Baredes S, Eloy JA. Laryngeal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: A Population-Based Analysis of Incidence and Survival. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:966-972. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Woodruff JM, Senie RT. Atypical carcinoid tumor of the larynx. A critical review of the literature. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1991;53:194-209. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Ferlito A, Silver CE, Bradford CR, Rinaldo A. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the larynx: an overview. Head Neck. 2009;31:1634-1646. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Kayhan FT, Başaran EG. Typical carcinoid tumor of the larynx in a woman: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:321. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Gnepp DR. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx. A critical review of the literature. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1991;53:210-219. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Chen XH, Bao YY, Zhou SH, Wang QY, Zhao K. Palatine Tonsillar Metastasis of Small-Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma from the Lung Detected by FDG-PET/CT After Tonsillectomy: A Case Report. Iran J Radiol. 2013;10:148-151. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Kulke MH, Shah MH, Benson AB 3rd, Bergsland E, Berlin JD, Blaszkowsky LS, Emerson L, Engstrom PF, Fanta P, Giordano T, Goldner WS, Halfdanarson TR, Heslin MJ, Kandeel F, Kunz PL, Kuvshinoff BW 2nd, Lieu C, Moley JF, Munene G, Pillarisetty VG, Saltz JA, Strosberg JR, Vauthey JN, Wolfgang C, Yao JC, Burns J, Freedman-Cass D; National comprehensive cancer network. Neuroendocrine tumors, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:78-108. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Ying HF, Bao YY, Zhou SH, Chai L, Zhao K, Wu TT. Submucosal small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx detected using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:1065-1069. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | Guofeng Z, Hongfang Y, Shuihong Z. [Neuroendocrine carcinoma of head and neck]. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015;50:260-264. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |