Published online Feb 16, 2017. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i2.61

Peer-review started: March 31, 2016

First decision: April 15, 2016

Revised: November 30, 2016

Accepted: December 13, 2016

Article in press: December 14, 2016

Published online: February 16, 2017

Processing time: 325 Days and 20.9 Hours

Inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) has always been considered a diagnostic challenge. Its rarity and resemblance to other more common pathological entities imposes that neither clinical nor radiological characteristics can lead to a definitive diagnosis. The surgical excision of the lesion is the ultimate approach for accurate diagnosis and cure. Moreover the true nature of IPT, its origin as a neoplastic entity or an over-reactive inflammatory reaction to an unknown trigger, has been a long debated matter. Surgery remains the treatment of choice. IPT is mostly an indolent disease with minimal morbidity and mortality. Local invasion and metastasis predict a poor prognosis. We hereby present a unique case of pulmonary IPT that was surgically excised, but recurred contralaterally, shortly thereafter. Despite no medical or surgical treatment for ten years, the lesion has remained stable in size, with neither symptoms nor extra-pulmonary manifestations.

Core tip: Inflammatory pseudotumor is considered a diagnostic challenge, with no one-self explained pathophysiology. Over-reactive inflammatory response to various triggering agents or even an entity with malignant potentials represents the two-sided pendulum. Accurate pathological identification lies on adequate tissue acquisition, which often occurs during surgical resection; the preferred treatment approach. Even though both local recurrence and metastasis represent a poor prognosis, its indolent course is not a well-known property, which we do here highlight in our patient with a 10-year follow up, possessing a stable and indolent disease.

- Citation: Degheili JA, Kanj NA, Koubaissi SA, Nasser MJ. Indolent lung opacity: Ten years follow-up of pulmonary inflammatory pseudo-tumor. World J Clin Cases 2017; 5(2): 61-66

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v5/i2/61.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i2.61

Inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) of the lung had been first described by Brunn[1] in 1939 and the term had been coined by Umiker et al[2] in 1954. Most commonly IPT presents in the lung and orbit. Other less common locations include: Liver, spleen, stomach[3], breast, esophagus, salivary glands[4], and the central nervous system[5]. It accounts for less than 1% of all lung specimens’ pathologies[6].

Given the heterogeneity in its true pathogenesis, several interchangeable terms have been linked to IPT such as: Plasma cell granuloma, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT), xanthoma, fibroxanthoma, and histiocytoma[7]. This resulted in some confusion among the medical societies regarding IPT true definition and description. A simple and clear classification has been reported which divided the spectrum of IPT into non-neoplastic versus neoplastic variants, the latter including IMT[8].

A 43-year-old female, smoker with a history of left tuberculous pleuritis treated in 1997, presented 6 years later to our clinic complaining of exertional shortness of breath of one year duration.

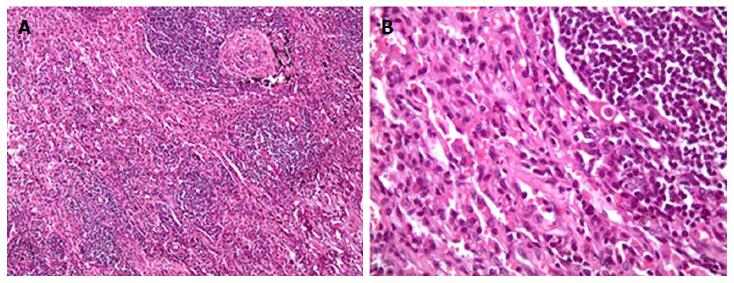

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed the presence of a left upper lobe mass 3.0 cm × 3.0 cm, along with prominent bilateral hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes. Pulmonary function tests showed mild restrictive disease. She underwent left lateral mini-thoracotomy followed by wedge resection of the lesion with mediastinal lymph node biopsy. Grossly, no parietal pleural involvement was noted, and no frozen section was sent, at that time, for intra-op identification. Pathology came out to be acute and chronic non-specific inflammation along with fibrosis (Figure 1). No treatment was initiated, and the patient was discharged home, advising close follow-up.

Ten years following her thoracotomy, the patient presented back for asymptomatic right middle lobe opacity, not resolving on several antibiotic regimens.

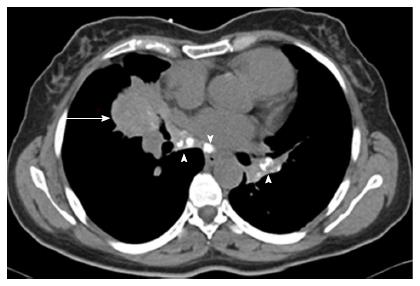

CT chest revealed a right middle lobe mass extending to the right lower lobe, with mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy (Figure 2).

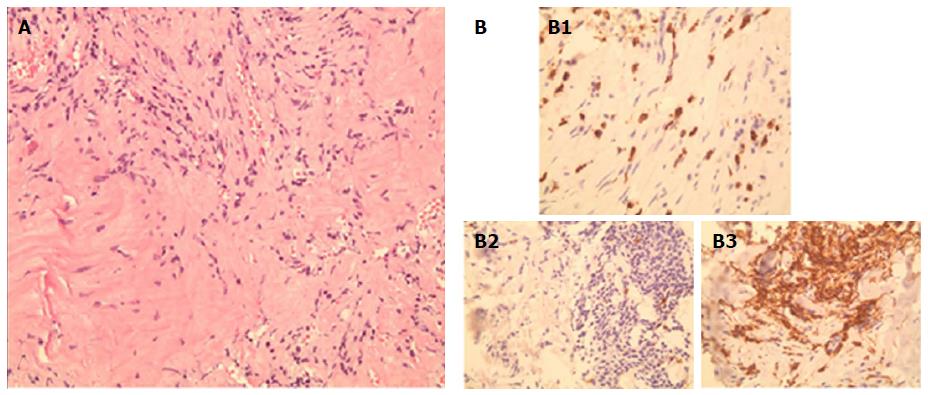

A CT-guided core biopsy of the middle lobe mass was performed. Histopathological examination revealed a matrix of spindle cells consistent of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, intermixed with inflammatory cells including leukocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes (Figure 3). A low mitotic activity was noted among cells, with no dysplasia. These findings highly suggest a pulmonary IPT of the lymphoplasmacytic subtype. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene mutation was absent on the tissues, and serum IgG4 level was 0.279 g/L (0.052-1.25 g/L). Pathologic reexamination of the previously resected left upper lobe lesion confirmed similar histopathological findings. Given the indolent course of the disease and the asymptomatic status, along with a financial burden on the patient, a watchful waiting approach was elected, instead of surgical resection, with CT of the chest, to be done, every 2 to 3 years.

Pulmonary IPT represents a distinct group of pathologies ranging from benign lesions as plasma cell granuloma to lesions with more malignant potentials as IMTs[9]. IPT of the lung is a rare entity, constituting around 0.7% of all lung tumors, and approximately 0.04% to 1.2% of all thoracotomies[10]. Most of IPT lesions occur in younger age groups, with no sex predilection[11]. In fact, IPT in the pediatric age group is mostly of neoplastic form (IMT). The more benign forms of IPT usually occur in the adult population[8].

The predominant infectious/inflammatory etiology: The pathogenesis of IPT is elusive. Inflammation in IPT has been attributed to a metabolic disturbance, pulmonary infection, and/or antigen-antibody interaction to an unknown agent[7]. Thirty percent of IPT cases are reported to be preceded by recurrent respiratory tract infections. Isolated pathogens include: Human Herpes Virus, Epstein Barr Virus, Nocardia, Mycoplasma, and Actinomycetes[4,12]. Repetitive respiratory insults will call for inflammatory cells to migrate to the insult site. Subsequently over-reactive inflammation results in proliferation and infiltration of inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes. This could explain the persistent elevation in serum inflammatory biomarkers, as C-reactive protein and erythrocytes sedimentation rate[10].

The genetic postulate:ALK gene has been used as a molecular surrogate to differentiate benign IPT from malignant IMT. ALK gene is present on chromosome 2p2. The gene encodes for tyrosine kinase receptors, and the resultant derangement will cause ALK protein over-expression and cell proliferation[4]. ALK positivity is only observed in IMT patients. Approximately half of IMT patients stain positive for ALK; yet show a great variation with age[8]. In contrast to other tumors that stain positive for ALK, ALK-positive IMT is associated with better prognosis than ALK-negative IMT, as the latter is associated with higher rate of metastasis[13].

Malignant potentials of IMT have been attributed to the derangement of ALK[14]. This proves to be pivotal in the medical treatment of IPT, as certain drugs can competitively inhibit such receptors and prohibit proliferation[15].

IPT vs IgG4-related diseases: A subset of IPT has been correlated with IgG4-related diseases[16]. “IgG4-related” sclerosing disease, a new disease entity, reflects the presence of abundant IgG4-plasma cells in the tissues[17,18]. IgG4 is the least abundant of all IgG subclasses, and accounts for less than 6% of the total IgG subclasses in the serum[19]. Serum IgG4 is elevated in certain pathological entities such as atopic dermatitis, pemphigus vulgaris, and sclerosing pancreatitis[10]. The IgG4-related IPT behaves differently than isolated IPT, as it responds greatly to steroids, precluding the need for surgical resection[8]. To confirm the diagnosis of IgG4-related pulmonary IPT, histological analysis is needed. A recent study reported the presence of IgG4-positive plasma cells in Plasma Cell Granuloma, a type of Pulmonary IPT[20]. This is contrary to serum IgG4 which is not always elevated[17]. Obliterative vasculitis also raises the probability of IPT over IMT[18]. The ratio of IgG4 over IgG-positive plasma cells, within tissue specimens, acts as a surrogate for diagnosis of IgG4-related IPT. A ratio greater than 50% is usually diagnostic[13].

Histologically, IPT consists of proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts intermingled with varying numbers of inflammatory cells including: Lymphocytes, polyclonal plasma cells, macrophages, and histiocytes[8]. Various histological classifications have been inaugurated, describing IPT. The most commonly used is that of Matsubara et al[21], and that of the World Health Organization (WHO)[22]. The former classifies IPT, according to dominant component cells and main histological characteristics, into 3 subtypes: Organizing Pneumonia, Fibrohistiocytoma, and Lymphoplasmacytic type; each constituting 44%, 44% and 12%, respectively. The WHO classification, on the other hand, divides IPT into compact spindle cell and hypocellular fibrous patterns[22].

Almost 70% of IPT cases are discovered incidentally. Such patients are either asymptomatic or complain of symptoms of other diseases[12]. Symptoms such as cough, hemoptysis, shortness of breath, and chest pain occur in 25% to 50% of patients[11]. Fever is not uncommon[22], mainly due to interleukins’ production (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6)[23].

Well-circumscribed solitary nodules, with peripheral lower lobar predilection, constitute the usual radiologic manifestation of IPT. In one study, this has been reported to occur in 87% of patients[24]. Multiple nodules do present in only 5% of cases[25]. Calcifications and lymphadenopathy are seen in 15% and 7% of cases, respectively[26]. Cavitary lesions and pleural effusions are quite rare findings[4]. Based on the radiological mode of presentation, it is difficult to differentiate IPT from other entities such as lung tumor or pulmonary tuberculosis; thus rendering IPT a clinical and a radiological challenge[11].

Transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) is not a favored diagnostic tool in IPT due to the small size of pieces, taken during the procedure, which renders the diagnosis a difficult call[11]. In fact, only 6.3% of IMT or IPT cases are diagnosed using TBLB[27]. Moreover, not uncommonly, lung tumors are surrounded by chronic inflammation because of the resulting insult to normal tissue, thus rendering diagnosis even more staggering. Definitive diagnosis of IPT is mainly achieved by surgical resection, which if complete, will lead to definitive cure in most cases.

The prognosis of IPT/IMT is variable. It usually depends on the tumor size and the magnitude of surgical resection[27]. Tumors greater than 3 cm are usually not amenable to complete resection. This implies a drop in long-term survival to less than 50%[12]. After complete resection, prognosis is favorable, with 5- and 10-year survival of 91% and 77%, respectively[28]. Metastatic lesions of IPT have approximately a 30-fold increase in recurrence rate, and are associated with a poor prognosis[12]. Positive margins after incomplete resection result in recurrence rate from 5% to 25%[10,13]. Pulmonary IMT, when not excised, shows continuum growth in approximately 8% of cases with a 5% risk of distant metastasis[13].

As previously stated, complete resection represents the most favorable and recommended diagnostic and therapeutic approach for pulmonary IPT. Patients who witness disease recurrence or those who do not fit for surgery may rarely benefit from other approaches including corticosteroids, chemo, and/or radiotherapy. Those modalities can also be used as adjuncts to suspected incomplete resection[29]. Radiotherapy has little to offer for these slow-growing lesions; hence radiation may cause more damage than cure. Corticosteroids’ use has shown contradictory results, though certain case reports showed complete regression after prolonged treatment[12]. Interestingly, many IPT lesions resolve completely after core biopsy. Such paradoxical behavior termed “spontaneous resolution”, is not a well understood phenomenon[13]. Methotrexate was used in some cases with modest results[30]. Crizotinib, a newly synthesized ALK inhibitor, has been used on a patient with pulmonary IMT, and showed sustained partial response[31].

In conclusion, this case, to the best of our knowledge, represents the longest reported follow up in an IPT patient. The absence of symptoms and the relative stability of the lesion, after 10 years, stipulate the natural and the benign behavior of this slowly-growing entity. The true outcome of IPT clearly requires further investigation. Greater capabilities in deciphering the diagnosis and approach to this disease, without relying on en bloc excision, lie on top of these investigations.

A 43-year-old woman, smoker, with history of left upper lobe mass resection, discovered after investigation for one year history of exertional dyspnea. Pathology back then showed acute and chronic non-specific inflammation with fibrosis. Ten years later, follow up on non-resolving right middle lobe opacity, despite multiple antibiotic regimens, resulted in a computed tomography (CT)-guided biopsy to be performed. Matrix of spindle cells intermixed with inflammatory cells was noticed.

Diagnosis of pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) was established from the core-guided biopsy.

Differential diagnosis of pulmonary IPT includes lung carcinoma and pulmonary tuberculoma; two entities that needed to be taken into consideration while suspecting pulmonary IPT.

In most isolated cases, laboratory data is normal except, in some cases, where pulmonary IPT is associated with IgG4 disease, for which the serum IgG4 subclass would be elevated.

Pulmonary IPT is difficult to diagnose, based on different radiological modalities alone. Its radiological resemblance with other entities, such as pulmonary tumor and tuberculosis, renders IPT a radiological challenge.

Histological examination of the CT-guided core biopsy revealed a matrix of spindle cells consistent with fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, intermixed with inflammatory cells, composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes.

En-bloc surgical resection with negative margins represents the core treatment for pulmonary IPT. Patients, who are ineligible for surgical intervention, can benefit from other suboptimal modalities including corticosteroids and chemo-radiation. The novel use of Crizotinib has proven its efficacy in IPT patients possessing anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positivity.

The present case report represents the longest follow-up, extending over a decade period, in a patient with pulmonary IPT, with no current or previous treatment. This highlights the indolent course of this disease entity, despite some other data reports evidence of local invasion or metastasis, even.

Pulmonary IPT constitutes less than 1% of all lung malignancies, and involves a spectrum of diseases, exhibiting benign behavior to more malignant potentials, as described by the inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMT). Histologically, IPT constitutes of spindle cells intermingled with inflammatory cells, which are arrayed in fascicles.

IPT of the lung is a rare disease entity, for which observation is regarded as a valid option, to be taken, but closely, into consideration.

The review is well structured and current enough. The article provides information that is useful for application to clinical practice.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Lebanon

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Nosotti M, Pereira-Vega A S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Brunn H. Two interesting benign lung tumors of contradictory histopathology. Remarks on the necessity for maintaining the Chest Tumor Registry. J Thorac Surg. 1939;9:119-131. |

| 2. | Umiker WO, Iverson L. Postinflammatory tumors of the lung; report of four cases simulating xanthoma, fibroma, or plasma cell tumor. J Thorac Surg. 1954;28:55-63. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Chen WC, Jiang ZY, Zhou F, Wu ZR, Jiang GX, Zhang BY, Cao LP. A large inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor involving both stomach and spleen: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:811-815. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Hammas N, Chbani L, Rami M, Boubbou M, Benmiloud S, Bouabdellah Y, Tizniti S, Hida M, Amarti A. A rare tumor of the lung: inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Häusler M, Schaade L, Ramaekers VT, Doenges M, Heimann G, Sellhaus B. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the central nervous system: report of 3 cases and a literature review. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:253-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Toma CL, Belaconi IN, Dumitrache-Rujinski S, Alexe M, Saon C, Leonte D, Bogdan MA. A rare case of lung tumor -- pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor. Pneumologia. 2013;62:30-32. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Morar R, Bhayat A, Hammond G, Bruinette H, Feldman C. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the lung: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Radiol. 2012;2012:214528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yi E, Aubry MC. Pulmonary pseudoneoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:417-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gleason BC, Hornick JL. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours: where are we now? J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:428-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 492] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fornell-Pérez R, Santana-Montesdeoca JM, García-Villar C, Camacho-García MC. Two types of presentation of pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumors. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;48:296-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kobashi Y, Fukuda M, Nakata M, Irei T, Oka M. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the lung: clinicopathological analysis in seven adult patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006;11:461-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kaitoukov Y, Rakovich G, Trahan S, Grégoire J. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the lung. Can Respir J. 2011;18:315-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bhagat P, Bal A, Das A, Singh N, Singh H. Pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor and IgG4-related inflammatory pseudotumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Virchows Arch. 2013;463:743-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: comparison of clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:509-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 627] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mologni L. Inhibitors of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:985-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mahajan VS, Mattoo H, Deshpande V, Pillai SS, Stone JH. IgG4-related disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:315-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Saab ST, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD, Olson SJ, Coffin CM. IgG4 plasma cells in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: inflammatory marker or pathogenic link? Mod Pathol. 2011;24:606-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tsuboi H, Inokuma S, Setoguchi K, Shuji S, Hagino N, Tanaka Y, Yoshida N, Hishima T, Kamisawa T. Inflammatory pseudotumors in multiple organs associated with elevated serum IgG4 level: recovery by only a small replacement dose of steroid. Intern Med. 2008;47:1139-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Van der Zee JS, Aalberse RC. Immunochemical characteristics of IgG4 antibodies. N Engl Reg Allergy Proc. 1988;9:31-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zen Y, Kitagawa S, Minato H, Kurumaya H, Katayanagi K, Masuda S, Niwa H, Fujimura M, Nakanuma Y. IgG4-positive plasma cells in inflammatory pseudotumor (plasma cell granuloma) of the lung. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:710-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Matsubara O, Tan-Liu NS, Kenney RM, Mark EJ. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the lung: progression from organizing pneumonia to fibrous histiocytoma or to plasma cell granuloma in 32 cases. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:807-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fisher RG, Wright PF, Johnson JE. Inflammatory pseudotumor presenting as fever of unknown origin. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1492-1494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rohrlich P, Peuchmaur M, Cocci SN, Gasselin ID, Garel C, Aigrain Y, Galanaud P, Vilmer E, Emilie D. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-1 beta production in a pediatric plasma cell granuloma of the lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:590-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Agrons GA, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Kirejczyk WM, Conran RM, Stocker JT. Pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor: radiologic features. Radiology. 1998;206:511-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Narla LD, Newman B, Spottswood SS, Narla S, Kolli R. Inflammatory pseudotumor. Radiographics. 2003;23:719-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kim TS, Han J, Kim GY, Lee KS, Kim H, Kim J. Pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor (inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor): CT features with pathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005;29:633-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen CK, Jan CI, Tsai JS, Huang HC, Chen PR, Lin YS, Chen CY, Fang HY. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung--a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;5:55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fabre D, Fadel E, Singhal S, de Montpreville V, Mussot S, Mercier O, Chataigner O, Dartevelle PG. Complete resection of pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumors has excellent long-term prognosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:435-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sanchez PG, Madke GR, Pilla ES, Foergnes R, Felicetti JC, Valle Ed, Geyer G. Endobronchial inflammatory pseudotumor: a case report. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33:484-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sunbul M, Cagac O, Birkan Y. A rare case of inflammatory pseudotumor with both involvement of lung and heart. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;61:646-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Butrynski JE, D'Adamo DR, Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Antonescu CR, Jhanwar SC, Ladanyi M, Capelletti M, Rodig SJ, Ramaiya N. Crizotinib in ALK-rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1727-1733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 727] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |