Published online Aug 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i8.380

Revised: April 29, 2014

Accepted: June 14, 2014

Published online: August 16, 2014

We report the first case of acute renal failure secondary to prucalopride, a novel agent for the treatment of chronic constipation. The 75 years old male patient was initiated on prucalopride after many failed treatments for constipation following a Whipple’s procedure for pancreatic cancer. Within four months of treatment his creatinine rose from 103 to 285 μmol/L (eGFR 61 decrease to 19 mL/min per 1.73 m2). He was initially treated with prednisone for presumed acute interstitial nephritis as white blood casts were seen on urine microscopy. When no improvement was detected, a core biopsy was performed and revealed interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. The presence of oxalate and calcium phosphate crystals were also noted. These findings suggest acute tubular necrosis which may have been secondary to acute interstitial nephritis or hemodynamic insult. The use of prednisone may have suppressed signs of inflammation and therefore the clinical diagnosis was deemed acute interstitial nephritis causing acute tubular necrosis. There are no previous reports of prucalopride associated with acute renal failure from the literature, including previous Phase II and III trials.

Core tip: Prucalopride is a novel agent used in the treatment of chronic constipation. We report the first case of acute renal failure secondary to prucalopride four months after treatment initiation. A core renal biopsy after prednisone therapy revealed interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. These findings suggested acute tubular necrosis secondary to acute interstitial nephritis. There are no previous reports of prucalopride associated with acute renal failure from the literature, including previous Phase II and III trials. This case reports highlights the need for monitoring renal function in all patients treated with prucalopride.

- Citation: Sivabalasundaram V, Habal F, Cherney D. Prucalopride-associated acute tubular necrosis. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(8): 380-384

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i8/380.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i8.380

Chronic constipation is very common and affects 14% of the general population[1]. The incidence rises with age, and is higher in women and those with lower socioeconomic status[2]. It is characterized by infrequent bowel and often associated with abdominal discomfort, bloating and cramps. Patients are susceptible to complications such as hemorrhoids and anal fissures. The consequences on quality of life, health care costs and activity impairment are also significant[3].

The treatment of constipation requires a multi-faceted approach which includes lifestyle changes, dietary adjustments, stool softeners, osmotic agents and laxatives[4,5]. Another target for intervention is the 5 hydroxytryptamine-4 (5-HT4) receptor. Until recently, drugs have lacked specificity for the 5-HT4 receptor resulting in an unfavourable risk-benefit ratio with side effects of serious cardiovascular arrhythmias[6,7]. Prucalopride however has demonstrated a high selectivity and affinity for this receptor in the gut with a high efficacy compared to placebo in patients with severe constipation[8-10] and in those who have failed previous laxative therapy[11,12]. The most common adverse effects were headache, nausea, diarrhea and abdominal pain, with no significant cardiovascular effects. Renal failure was not found to be associated with prucalopride and no change in chemical laboratory data was reported from baseline in all of the phase 3 studies[8,12,13]. Randomized trials in elderly patients also found prucalopride to be safe with no effect on renal or cardiac function[10,14]. We report the first case of pruaclopride associated renal failure which was irreversible following discontinuation of the medication.

A 75 years old male developed chronic constipation following a Whipple’s pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer 19 mo earlier. Over this period, he had multiple emergency room visits for abdominal cramps and pain which were on occasion related to severe constipation and obstipation. He required regular cleansing regimens in hospital, and repeated upper and lower endoscopies revealed no significant pathology. He was referred to a gastroenterologist and his pain resolved with discontinuation of his pancrealipase preparation. After failing several months of therapy for constipation with various bulking, osmotic and stimulant laxatives, he was initiated on prucalopride (Resotran), a new enterokinetic agent, at a dose of 2 mg once daily.

Besides his Whipple’s procedure, his surgical history is also significant for an open prostatectomy nine years prior for benign prostatic hyperplasia, remote appendectomy, and a hernia repair. His medical history includes hypertension, dyslipidemia, and a cerebrovascular ischemic stroke with minimal neurologic deficits. His medications at this time were clopidogrel, pantoprazole, candesartan, indapamide, gabapentin, sennoside, as well as 30 g of fiber daily.

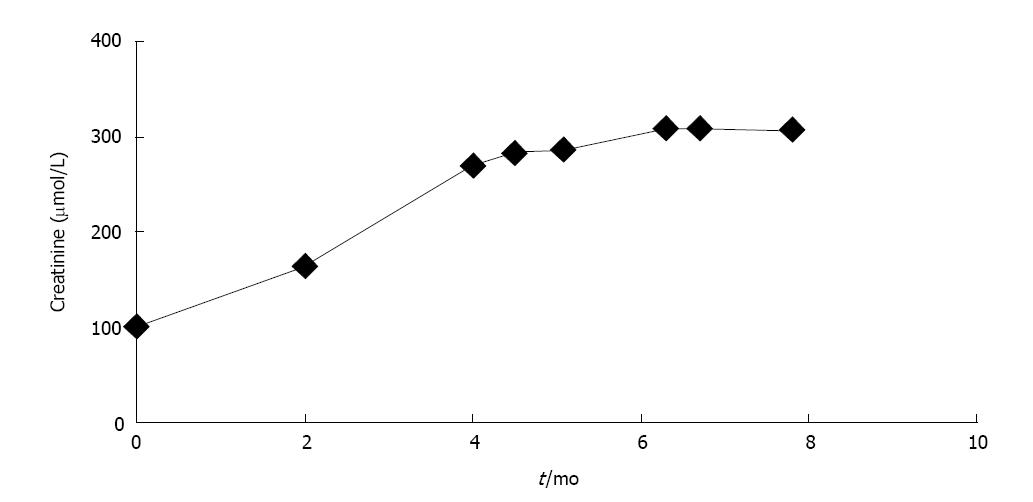

The patient was seen four months after the initiation of prucalopride and was now having regular bowel movements for the first time since his Whipple’s surgery. He required no further admissions to hospital and his quality of life significantly improved while using prucalopride as the sole agent for management of his constipation. It was however noted that his creatinine was had risen from a baseline of 103 (eGFR baseline 61 mL/min per 1.73 m2, stable for at least 4 years) to 165 μmol/L (eGFR 35 mL/min per 1.73 m2) in two months, and further to 270 μmol/L (eGFR 19 mL/min per 1.73 m2) by four months (Figure 1). He endorsed no symptoms of decreased oral intake, oliguria, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, peripheral swelling, or shortness of breath. He also denied any irritative or obstructive urinary symptoms. There were no recent changes to his medications, or any use of over the counter medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. His candesartan was held and he was referred to a nephrologist for an urgent assessment.

At this appointment he was found to have a normal blood pressure on examination, with no signs of a rash, peripheral edema, or volume overload. His blood work now demonstrated an elevated creatinine of 285 μmol/L at 4.5 mo following prucalopride administration. A complete work up for other renal disease including glomerular based diseases was negative and the patient did not have peripheral eosinophilia. Urinalysis showed +1 proteinuria, trace blood, and urine microscopy revealed many white blood cell casts. An ultrasound of his kidneys showed no signs of obstructive uropathy and Doppler examination of his renal arteries and veins were normal. He was diagnosed with acute interstitial nephritis secondary to his exposure to prucalopride and was instructed to stop this medication. He was started on prednisone 40 mg daily for one week, followed by a taper of 5 mg weekly. The patient was seen in follow-up two weeks later for repeat blood work. Unfortunately his creatinine remained elevated at 310 μmol/L while on prednisone at a dose of 30 mg daily. Given the lack of renal recovery, a renal biopsy was performed within one week.

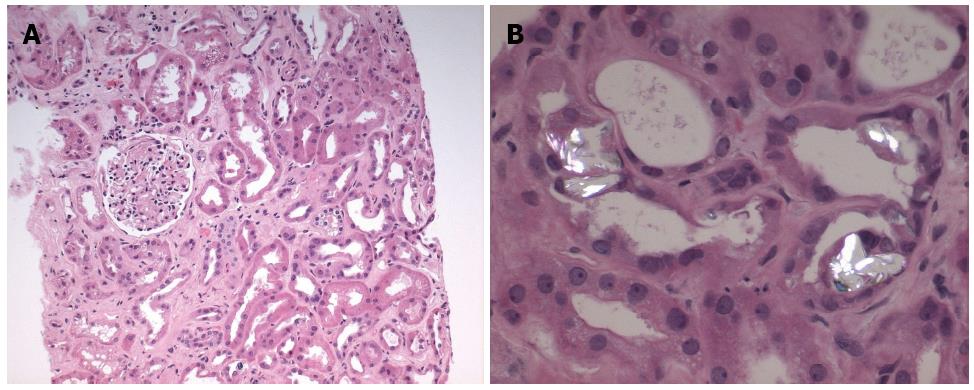

The core biopsy specimen from the left kidney showed 11 of 39 glomeruli globally sclerosed, while the remainder of the glomeruli showed no increase in mesangial matrix or cellularity (Figure 2A). There was minimal interstitial inflammation, with moderate degenerative and regenerative changes within the tubules. There was moderate (40%) interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. There was no arteriolar hyalinosis and moderate arterial sclerosis. Many of the tubules also contained oxalate and calcium phosphate crystals (Figure 2B). Immunofluorescence was negative for immunoglobulin A, G and M, as well as C3, C1q, kappa or lambda. Electron microscopy of the non-sclerosed glomeruli revealed no immune-type deposits, nor any tubuloreticular inclusions. The glomerular basement membranes were mildly wrinkled and within normal limits of thickness. There was moderate effacement of the podocyte foot processes (30%). These findings were consistent with acute tubular necrosis with no evidence for interstitial nephritis.

According to the Naranjo probability score of adverse drug reactions[15], our patient’s case was classified as a ‘probable adverse drug reaction’ of prucalopride induced kidney injury. Points were given for temporal causality, lack of an alternative cause of the reaction, lack of progression with drug discontinuation, and objective confirmation of kidney injury with the renal biopsy.

The patient remained on prednisone at 20 mg daily until seen in follow-up three weeks later. Repeat creatinine remained elevated at 309 μmol/L. His prednisone taper was resumed at 5 mg per week and was ultimately discontinued since there were no signs of ongoing inflammation in the biopsy specimen. The patient unfortunately did not have any further renal recovery and his symptoms of constipation returned while off prucalopride. The search for alternative regimen to treat his chronic constipation is ongoing.

Prucalopride is a novel highly selective 5-HT4 receptor agonist developed for the treatment of chronic constipation among patients with an inadequate response to laxatives. The safety of this medication was assessed in all the Phase II trials, and in three Phase III pivotal trials. A total of 1974 patients were evaluated in the phase III trials, with 1313 receiving prucalopride[8,12,13]. The most frequent adverse events reported were headache, abdominal pain, nausea and diarrhea, with most symptoms occurring on the first day. None of the phase III trials reported changes in renal function as measured by blood work at baseline and throughout the study. Two smaller placebo-controlled randomized trials in elderly patients with a mean age of 76 and 83, randomized a total of 301 patients to prucalopride[10,14]. The same profile of adverse events were seen in these trials with elderly patients as the larger phase III trials. However, in both trials, prucalopride was only administered for 4 wk and while no kidney injury was reported after short-term use, there is a lack of long-term data in the elderly. Numerous other smaller randomized trials with prucalopride also found no associated reports of renal impairment[9,11,16,17]. Elderly patients are at increased risk for baseline renal dysfunction. In the patient described in this report, although stable for least 4 years, the eGFR of 61 mL/min per 1.73 m2, likely reflected some degree of underlying chronic kidney disease. The elderly patient demographic and potential for underlying chronic kidney disease emphasize the importance of including this group in study trials for safety outcomes.

Our case demonstrates the first report of acute tubular necrosis associated with prucalopride administration. A thorough search on PubMed, Embase and Medline demonstrated no other reports of acute kidney injury secondary to prucalopride. A search for an association with alternative serotonin receptor agonists, such as cisapride or tegaserod, with kidney injury also found no previous case reports. Whether the acute tubular necrosis was due to acute interstitial nephritis or hemodynamic insult cannot be definitively known in this case, since the patient was treated empirically with steroids based on the prominent white blood cell casts on urinalysis. However it remains likely that interstitial inflammation was suppressed by steroid administration prior to the renal biopsy and the working clinical diagnosis was therefore acute interstitial nephritis causing acute tubular necrosis.

The key feature which differentiates prucalopride from other 5-HT4 receptor agonists such as cisapride and tegaserod is its increased selectivity for its receptor[18]. The lack of selectivity of the other older agents resulted in an appreciable affinity for other receptors, channels or transporters. For example, cisapride had an affinity for the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) K+ channel found in cardiac cells[19] while tegaserod would also bind to 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptors[18]. These agents subsequently demonstrated cardiovascular side effects which were independent of their action on the 5-HT4 receptor[19,20]. The characteristic of high selectivity is important as serotonin receptors are found throughout the body, including the kidney. The primary receptors in the kidney are the 5-HT2 receptors on smooth muscle cells and the 5-HT1 receptors on endothelial cells[21]. Stimulation of the 5-HT2 receptors directly causes renal vasoconstriction, while activation of 5-HT1 receptors leads to vasodilation indirectly via nitric oxide[22]. It has been found that administration of serotonin impairs autoregulation of the glomerular filtration rate of the kidney, leaving it vulnerable to ischemic damage[23]. While prucalopride has agonistic effects on the serotonin receptor, given that it has not been shown to activate the specific subtypes of 5-HT2 and 5-HT1, this mechanism of kidney injury is less likely. It is not known whether the concurrent use of candesartan in this patient may have also played a role in the development of acute tubular necrosis, since angiotensin II blockade can also cause impaired renal autoregulation and a decline in glomerular filtration rate through post-glomerular vasodilatation.

Our patient’s renal biopsy also demonstrated increased deposition of crystals, with predominantly oxalate crystals as well as calcium phosphate crystals. Increased absorption of oxalate from the colon occurs in fat malabsoprtion states, such as pancreatic insufficiency[24]. In such instances, calcium preferentially binds to free fatty acids instead of oxalate, which allows the free soluble oxalate to be absorbed through the colon. Other factors which can increase oxalate absorption include the presence of bile salts[25] and the absence of bacteria such as Oxalobacter formigenes and certain strains of Entercoccus fecalis which are able to degrade oxalate[26]. Our patient had discontinued his pancrealipase preparation at the time prucalopride was started due to side effects of abdominal pain. Given his history of Whipple’s pancreatectomy and the discontinuation of his pancreatic replacement enzymes, this fat malabsorption state may have induced hyperoxaluria.

Oxalate nephropathy can occur from tubular obstruction caused by calcium oxalate crystals, or by direct tubular injury which results in progressive tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis[25]. It is also common to see small numbers of oxalate crystals within tubules after acute tubular necrosis as well as in other chronic renal impairment conditions. Given the mixture of both oxalate and calcium phosphate crystals in our patient’s renal biopsy, an underlying oxalate nephropathy as the etiology of the acute kidney injury is less probable. In addition, the creatinine stabilized with cessation of prucalopride and the patient did not yet resume his pancrealipase preparation. Cases of oxalate nephropathy reported in the literature are often associated with oliguria and a marked decline in renal function requiring hemodialysis[27]. Fortunately, our patient’s renal failure was not as severe. Follow up urinalyses have failed to demonstrate crystals of any type, further suggesting that a crystal nephropathy is not playing an important contribution to the patient’s renal failure. Furthermore, high-fluid intake and low oxalate diet recommendations along with calcium carbonate supplements have not been associated with improved renal function.

In conclusion, given the lack of literature to support prucalopride and other serotonin receptor agonists as nephrotoxins, our patient’s case of acute renal failure was treated initially as allergic interstitial nephritis. However, when his renal function did not improve with discontinuation of the medication and prednisone therapy, a renal biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. This case demonstrates the importance of a renal biopsy when the diagnosis is unclear or when there is lack of improvement with therapy. In addition, this case also highlights the importance of routine blood work to follow cell count, biochemistry and renal function when starting a medication which is new to both the patient and the medical community. Adverse effects which were not documented by clinical trials may still occur in our patients and reporting of such outcomes is required for ongoing drug safety and monitoring. In addition, given the limited long-term data available for elderly patients, and unreliability of serum creatinine in estimating renal function, a lower 1 mg of prucalopride should be initiated in this population. Without routine blood work, this case of renal failure may have been missed until the patient presented with more significant symptoms related to renal failure such as oliguria, vomiting, volume overload or uremia.

A 75 years old gentleman initiated on prucalopride for chronic constipation with subsequent elevation of serum creatinine from 100 μmol/L to 270 μmol/L within four months.

He was treated with prednisone for presumed acute interstitial nephritis and a subsequent renal biopsy demonstrated acute tubular necrosis secondary to acute interstitial nephritis.

Acute interstitial nephritis secondary to a drug allergic reaction, oxalate nephropathy, and acute tubular necrosis following hemodynamic insult, angiotensin II blockade or interstitial nephritis.

Serum creatinine rose from a baseline of 103 μmol/L to a peak of 310 μmol/L and urine microscopy revealed many white cell casts.

Abdominal ultrasound showed no signs of obstructive uropathy, and Doppler examination was negative for renal artery stenosis.

A renal biopsy was performed after cessation of prucalopride and administration of prednisone revealing moderate interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy with deposition of oxalate and calcium phosphate crystals.

Therapy with prednisone was initiated once white cell casts were seen on urinary microscopy and prucalopride was discontinued resulting in stabilization of the serum creatinine but no further recovery of renal function.

This is the first case of acute renal failure reported in the literature, with no previous occurrences documented from several previous Phase II and III trials.

Prucalopride is a novel highly selective 5 hydroxytryptamine-4 receptor agonist developed for the treatment of chronic constipation after failure of laxative therapy.

This case highlights the need for monitoring of routine blood work with cell count, biochemistry and renal function when using medications new to both the patient and the medical community as previously undocumented adverse events may develop.

This is an important case report in regard to clinical use of prucalopride.

P- Reviewer: Du C, Gurjar M S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Suares NC, Ford AC. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1582-1591; quiz 1581, 1592. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 503] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1360-1368. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 564] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 495] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sun SX, Dibonaventura M, Purayidathil FW, Wagner JS, Dabbous O, Mody R. Impact of chronic constipation on health-related quality of life, work productivity, and healthcare resource use: an analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2688-2695. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 131] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tack J, Müller-Lissner S. Treatment of chronic constipation: current pharmacologic approaches and future directions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:502-508; quiz 496. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force. An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100 Suppl 1:S1-S4. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 174] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gardner VY, Beckwith JV, Heyneman CA. Cisapride for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation. Ann Pharmacother. 1995;29:1161-1163. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Kamm MA, Müller-Lissner S, Talley NJ, Tack J, Boeckxstaens G, Minushkin ON, Kalinin A, Dzieniszewski J, Haeck P, Fordham F, Hugot-Cournez S, Nault B. Tegaserod for the treatment of chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multinational study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:362-372. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 138] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, Vandeplassche L. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2344-2354. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 436] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ke M, Zou D, Yuan Y, Li Y, Lin L, Hao J, Hou X, Kim HJ. Prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation in patients from the Asia-Pacific region: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:999-e541. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Müller-Lissner S, Rykx A, Kerstens R, Vandeplassche L. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of prucalopride in elderly patients with chronic constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:991-998, e255. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Coremans G, Kerstens R, De Pauw M, Stevens M. Prucalopride is effective in patients with severe chronic constipation in whom laxatives fail to provide adequate relief. Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Digestion. 2003;67:82-89. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tack J, van Outryve M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Vandeplassche L. Prucalopride (Resolor) in the treatment of severe chronic constipation in patients dissatisfied with laxatives. Gut. 2009;58:357-365. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 217] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Quigley EM, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R, Ausma J. Clinical trial: the efficacy, impact on quality of life, and safety and tolerability of prucalopride in severe chronic constipation--a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:315-328. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Camilleri M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Robinson P, Vandeplassche L. Safety assessment of prucalopride in elderly patients with constipation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:1256-e117. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, Janecek E, Domecq C, Greenblatt DJ. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7061] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7634] [Article Influence: 177.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sloots CE, Rykx A, Cools M, Kerstens R, De Pauw M. Efficacy and safety of prucalopride in patients with chronic noncancer pain suffering from opioid-induced constipation. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2912-2921. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 101] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Krogh K, Jensen MB, Gandrup P, Laurberg S, Nilsson J, Kerstens R, De Pauw M. Efficacy and tolerability of prucalopride in patients with constipation due to spinal cord injury. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:431-436. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | De Maeyer JH, Lefebvre RA, Schuurkes JA. 5-HT4 receptor agonists: similar but not the same. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:99-112. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 182] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mohammad S, Zhou Z, Gong Q, January CT. Blockage of the HERG human cardiac K+ channel by the gastrointestinal prokinetic agent cisapride. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H2534-H2538. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Busti AJ, Murillo JR, Cryer B. Tegaserod-induced myocardial infarction: case report and hypothesis. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:526-531. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lameire NH. Serotonin and the regulation of renal blood flow in acute renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:LII-LIV. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Van Nueten JM. Serotonin and the blood vessel wall. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1985;7 Suppl 7:S49-S51. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Endlich K, Kühn R, Steinhausen M. Visualization of serotonin effects on renal vessels of rats. Kidney Int. 1993;43:314-323. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dobbins JW, Binder HJ. Importance of the colon in enteric hyperoxaluria. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:298-301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 133] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wandzilak TR, Williams HE. The hyperoxaluric syndromes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1990;19:851-867. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Allison MJ, Cook HM, Milne DB, Gallagher S, Clayman RV. Oxalate degradation by gastrointestinal bacteria from humans. J Nutr. 1986;116:455-460. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Hill P, Karim M, Davies DR, Roberts IS, Winearls CG. Rapidly progressive irreversible renal failure in patients with pancreatic insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:842-845. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |