Published online May 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i5.146

Revised: March 18, 2014

Accepted: April 11, 2014

Published online: May 16, 2014

We report a case of primary colonic lymphoma incidentally diagnosed in a patient presenting a gallbladder attack making particular attention on the diagnostic findings at ultrasound (US) and total body computed tomography (CT) exams that allowed us to make the correct final diagnosis. A 85-year-old Caucasian male patient was referred to our department due to acute pain at the upper right quadrant, spreaded to the right shoulder blade. Patient had nausea and mild fever and Murphy’s maneuver was positive. At physical examination a large bulky mass was found in the right flank. Patient underwent to US exam that detected a big stone in the lumen of the gallbladder and in correspondence of the palpable mass, an extended concentric thickening of the colic wall. CT scan was performed and confirmed a widespread and concentric thickening of the wall of the ascending colon and cecum. In addition, revealed signs of microperforation of the colic wall. Numerous large lymphadenopathies were found in the abdominal, pelvic and thoracic cavity and there was a condition of splenomegaly, with some ischemic outcomes in the context of the spleen. No metastasis in the parenchimatous organs were found. These imaging findings suggest us the diagnosis of lymphoma. Patient underwent to surgery, and right hemicolectomy and cholecystectomy was performed. Histological examination confirmed our diagnosis, revealing a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The patient underwent to Cyclophosphamide, Hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovin, Prednisone chemotherapy showing only a partial regression of the lymphadenopathies, being in advanced stage at the time of diagnosis.

Core tip: The authors report their experience with a largely primary colonic lymphoma (PCL) incidentally detected in a patient presenting a gallbladder attack. PCL is a rare disease (less than 1% of all colorectal malignancies). Symptoms are unspecific and it is usually quite advanced by the time diagnosis is made. In this case, patient showed symptoms of gallbladder disease and presented a large bulky mass at physical exam. The authors pay particular attention in describing clinic and diagnostic findings which suggested the correct final diagnosis of PCL. The role of ultrasound and computed tomography exams with the respective radiological features are described.

- Citation: Gigli S, Buonocore V, Barchetti F, Glorioso M, Di Brino M, Guerrisi P, Buonocore C, Giovagnorio F, Giraldi G. Primary colonic lymphoma: An incidental finding in a patient with a gallstone attack. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(5): 146-150

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i5/146.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i5.146

Lymphomas are haematological malignancies which could have extranodal manifestations in approximately 40% of cases. The gastro-intestinal tract is the most common extranodal localization of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) with a rare involvement of large bowel. The diagnostic criteria were firstly described by Barbaryan et al[1] in 1961.

Overall, primary colonic lymphoma (PCL) accounts for 1.4% of all cases of NHLs and represents only the 0.2%-0.6% of all large-bowel malignancies[2]. The most common histological types, in according with the Ann-Arbor classification, were: diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with frequency rate ranging from 47% to 81%, Mantle-cell lymphomas and Burkitt’s lymphomas[3-5]. We report a case of PCL in a patient presenting with a gallbladder attack.

A 85-year-old Caucasian male patient came to our Department of Radiological Sciences complaining of acute pain at the right flank, spreading to the back right shoulder blade area. The patient had nausea and mild fever. The pain arose during the night. At physical examination, the patient appeared pale. Murphy’s maneuver was positive. Patient referred at least other two similar attacks of pain during the past 3 years.

Abdominal palpation revealed a voluminous bulky mass with a maximum diameter of about 8 cm in the right flank, fixed in the deep layers. Moreover, the patient referred weight loss in the last six months, persistent low-grade fever in the evening and loss of appetite.

The blood investigations revealed microcytic anemia (HB 8.8 mg/dL), slight increase of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and alkaline phosphatase (187 U/L). It was also observed an increase of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (30 mm/s) and of the C-reactive protein (128 mg/L). No further significant changes were found in the laboratory exams.

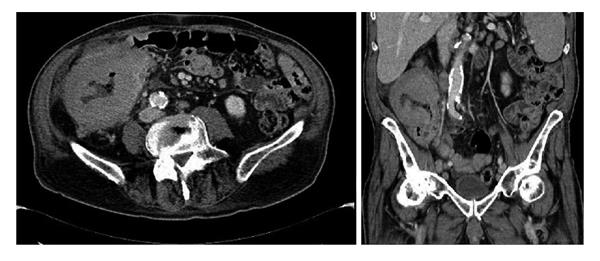

Therefore, it was performed an ultrasound (US) examination that detected a stone containing slightly thick walled gallbladder (maximum diameter of about 1.5 cm). Intra and extra-hepatic bile ducts were not dilated. The liver presented regular shape, normal size and no solid pathologic lesions were found. In the upper right quadrant, in correspondence of the palpable mass, there was a concentric thickening of the wall of the ascending colon, which assumed the appearance of a solid mass of 10 mm in maximum diameter (Figure 1).

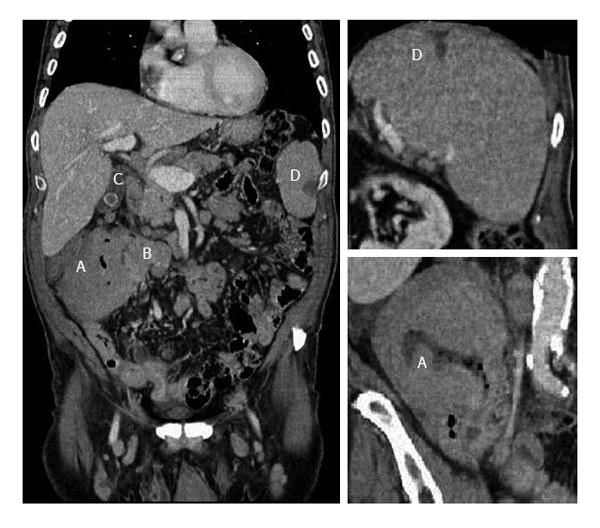

We decided to perform a total body computed tomography (CT) scan which confirmed, close to the hepatic flexure, a widespread and concentric thickening of the wall of the ascending colon (maximum thickness 40 mm) extended in cranio-caudal direction for 10 cm.

In the submucosa, there were signs of microperforation with millimetric air bubbles in the context of the colic wall. The perivisceral and omental fatty tissue was inhomogeneous.

On the medial side of the lesion there was a great necrotic enlarged lymph node (dimensions: 45 mm of longitudinal diameter and 66 mm of transverse diameter).

Numerous lymphadenopathies were found in the abdominal and pelvic cavity, the most numerous of them lying in the inter-aorto-caval space and along the course of the splenic vein and the iliac vessels bilaterally. In addition, the spleen was enlarged (longitudinal diameter of 18 cm) with some parenchymal hypodense areas in the context that could be indicative of ischemic outcomes (Figures 2 and 3).

Not further significant alterations were found in the liver and in the other parenchymatous organs.

Some lymphadenopathies were found also in the thoracic cavity, located in the pretracheal and para-esophageal space (maximum diameter 14 mm).

In the cardio-phrenic space, bilaterally, there were other small pathologic lymph nodes.

Considering the morphology of the colonic thickening, which seemed to be expansive rather than infiltrative, the presence of multiple lymphadenopathies, the condition of splenomegaly and the absence of involvement of the liver and peritoneum, the diagnosis of lymphoma was suspected.

The patient was sent to surgery and a right hemicolectomy associated with loco-regional lymphadenectomy and cholecystectomy was performed.

Histological examination of the surgical specimen revealed a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79A, and BCL6 positive.

The patient underwent six cycles of chemotherapy [Cyclophosphamide, Hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovin, Prednisone (CHOP) regimen] and showed only a partial regression of the lymphadenopathies.

PCL is extremely rare, but may be increasing in frequency; it represents less than 1% of all colorectal malignancies[6,7]. There is a male predominance for these tumors, (twice as often in males compared with females) and the maximal incidence is found in the 50-65 year age group, with a mean age of 55 years[2].

There are not well-defined risk factors related with this disease and up to now the most common identified are: the immunosuppression (HIV or long-term corticosteroid therapy) and the inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD)[8].

Therefore, PCL can be present for a long period of time without causing symptoms and the diagnosis often is made in an advanced stage.

The most common signs and symptoms are unspecific, such as: abdominal pain (66.8%), anorexia and weight loss (43%) and an abdominal palpable mass (41.3%). Less common presentations are: bloody stool (23%), acute abdomen, microcytic anemia and rectal bleeding[2,5].

Our patient did not present any risk factors or specific symptoms for PCL, and diagnosis was incidental in occasion of a gallbladder attack.

Imaging methods were essential to perform a correct diagnosis, particularly US examination confirmed the presence of the large bulky mass found at physical exam and CT allowed us to suggest the diagnosis of lymphoma and to evaluate the disease extension.

Radiographic findings associated with PCL often could be nonspecific, sharing similarities with other types of colorectal disease, such as colorectal carcinoma and IBD[9].

In our case, CT gave us a high suspicion of PCL showing regional and systemic lymph nodes involvement, spleen enlargement, and absence of metastasis. The lesion was located in the cecum-ascending colon. These locations are the most common sites for colorectal lymphoma (respectively 57% and 18% of cases) probably because more lymphoid tissue is present in this region. Other sites involved are the transverse, recto-sigmoid colon (10%) and the descending colon (5%)[10].

The management of PCL is various, based on the extension of the disease and on clinical status of the patients at the time of diagnosis[11]. The treatment of PCL varies from chemotherapy alone to multimodal therapies combining surgery, chemotherapy, and even radiation therapy. The administration of chemotherapy and particularly the CHOP regimen remains the mainstay in the treatment management[12].

According to many authors the surgical treatment may provide important prognostic information, including histology, tumor extent and stage[13,14].

In the absence of disseminated disease, surgical resection is generally performed. The surgical approach may be used also as a therapy for local control in patients with aggressive lymphoma and to prevent complications like bleeding, perforation or intussusception. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma of the large bowel is generally treated with a uniform therapeutic approach: aggressive surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy[15].

Our patient directly underwent to a surgical approach, in consideration of the large size of the tumoral mass and in order to avoid complications and particularly the risk of perforation, in fact the rate of spontaneous perforation in patients with PCL is 5%-11.5% suggested by the presence of air bubbles. In addition, since the patient had recurrent attack of pain due to the gallstones, cholecystectomy was performed.

After surgery which confirmed the suspected diagnosis of lymphoma, he underwent CHOP scheme chemotherapy with a partial remission of disease. This outcome can be explained by the fact that, although resection plays an important role in the local control of the disease and in preventing bleeding and/or perforation, it rarely eradicates the lymphoma by itself.

Prognosis of PCL depends on numerous factors but the stage at diagnosis and the histological grade are the most important elements affecting survival rate[16]. Our patient showed advanced disease, in fact warning signs of lymphoma are so subtle that it may take some time before realizing that there is a serious problem. The age of the patient could have influenced the promptness of diagnosis, in fact ancient patients may underestimate symptoms for a long time[3,17].

The median survival in cases of advanced disease is generally low, ranging from 24 to 36 mo. Unfortunately, relapses are frequent (rates range from 33% to 75%), and most of them occur within the first 5 years after resection with diffuse disease[18,19].

In conclusion PCL is a rare disease. Often it is diagnosed in advanced state. Diagnostic imaging modalities, and particularly CT, have a fundamental role in the diagnosis of lymphomas. If CT reveals an infiltrative tumor with enlarged lymph nodes in the abdomen or pelvis, lymphoma should be highly taken into account in the differential diagnosis. The prediction of prognosis and the planning of a suitable therapeutic approach is essential for the patients and CT allows an accurate staging of the disease[20].

A 85-year-old male with acute pain at the right flank, presented a gallstone attack and a large bulky mass in the abdomen.

Positivity to Murphy’s maneuver, low-grade fever, weight loss and a palpable voluminous bulky mass in the right flank.

Colorectal carcinoma, Inflammatory bowel diseases.

HB 8.8 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 187 U/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 30 mm/s and C-reactive protein 128 mg/L.

Ultrasound (US) examination detected a stone in the lumen of the gallbladder and a concentric thickening of the wall of the ascending colon; computed tomography (CT) confirmed the thickening of the wall of the cecum-ascending colon and revealed also signs of microperforation in the submucosa, numerous lymphadenopathies and a condition of splenomegaly.

The histological examination of the surgical specimen revealed a diffuse large B cell lymphoma CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79A, and BCL6 positive.

The patient underwent to surgery (right hemicolectomy, loco-regional lymphadenectomy and cholecystectomy); in addition, underwent to six cycles of chemotherapy [Cyclophosphamide, Hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovin, Prednisone (CHOP) regimen].

The latest studies confirmed that primary colonic lymphoma (PCL) is a very rare disease and that diagnosis is often incidental; in the authors’ case report, diagnosis was made in advanced stage and we chose for a surgical approach before chemotherapy, according to some authors, for locoregional control of disease and to prevent complications.

CHOP is the acronym of a chemotherapy scheme used in the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphomas consisting of an alkylating agent (Cyclophosphamide), an intercalating agent (Hydroxydaunorubicin), a mitotic inhibitor (Oncovin) and a corticosteroid (Prednisone).

This case report describes the diagnostic features of PCL and the radiological findings of this rare colonic disease, that should be considered in order to make a correct differential diagnosis, particularly stressing the role of US and CT.

The strength of this article is that it well describes the radiological features of PCL and the case is really remarkable. The histological and immunochemical profile has been included.

P- Reviewers: Boffano P, Movahed A, Panciani PP S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Barbaryan A, Ali AM, Kwatra SG, Saba R, Prueksaritanond S, Hussain N, Mirrakhimov AE, Vladimirskiy N, Zdunek T, Gilman AD. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the ascending colon. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:85-88. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chang SC. Clinical features and management of primary colonic lymphoma. Formosan J Surg. 2012;45:73-77. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dionigi G, Annoni M, Rovera F, Boni L, Villa F, Castano P, Bianchi V, Dionigi R. Primary colorectal lymphomas: review of the literature. Surg Oncol. 2007;16 Suppl 1:S169-S171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bairey O, Ruchlemer R, Shpilberg O. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of the colon. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8:832-835. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Wong MT, Eu KW. Primary colorectal lymphomas. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:586-591. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Wyatt SH, Fishman EK, Hruban RH, Siegelman SS. CT of primary colonic lymphoma. Clin Imaging. 1994;18:131-141. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | She WH, Day W, Lau PY, Mak KL, Yip AW. Primary colorectal lymphoma: case series and literature review. Asian J Surg. 2011;34:111-114. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Stanojevic GZ, Nestorovic MD, Brankovic BR, Stojanovic MP, Jovanovic MM, Radojkovic MD. Primary colorectal lymphoma: An overview. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;3:14-18. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ghai S, Pattison J, Ghai S, O’Malley ME, Khalili K, Stephens M. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma: spectrum of imaging findings with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2007;27:1371-1388. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 116] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Smith C, Kubicka RA, Thomas CR. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Radiographics. 1992;12:887-899. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Beaton C, Davies M, Beynon J. The management of primary small bowel and colon lymphoma--a review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:555-563. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hay AE, Meyer RM. Balancing risks and benefits of therapy for patients with favorable-risk limited-stage Hodgkin lymphoma: the role of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine chemotherapy alone. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2014;28:49-63. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Biondi A, Motta S, Di Giunta M, Crisafi RM, Zappalà S, Rapisarda D, Basile F. [The use of laparoscopy for diagnosis and stadiation of the lymphomas]. Ann Ital Chir. 2009;80:445-447. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Nakamura S, Matsumoto T. Gastrointestinal lymphoma: recent advances in diagnosis and treatment. Digestion. 2013;87:182-188. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Lai YL, Lin JK, Liang WY, Huang YC, Chang SC. Surgical resection combined with chemotherapy can help achieve better outcomes in patients with primary colonic lymphoma. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:265-268. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Radić-Kristo D, Planinc-Peraica A, Ostojić S, Vrhovac R, Kardum-Skelin I, Jaksić B. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma in adults: clinicopathologic and survival characteristics. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:413-417. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | De Luca d’Alessandro E, Bonacci S, Giraldi G. Aging populations: the health and quality of life of the elderly. Clin Ter. 2011;162:e13-e18. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Stanojević GZ, Stojanović MP, Stojanović MM, Krivokapić Z, Jovanović MM, Katić VV, Jeremić MM, Branković BR. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of the large bowel-clinical characteristics, prognostic factors and survival. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2008;55:109-114. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Lee J, Kim WS, Kim K, Ko YH, Kim JJ, Kim YH, Chun HK, Lee WY, Park JO, Jung CW. Intestinal lymphoma: exploration of the prognostic factors and the optimal treatment. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:339-344. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Fishman EK, Kuhlman JE, Jones RJ. CT of lymphoma: spectrum of disease. Radiographics. 1991;11:647-669. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |