Published online Oct 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i30.11074

Peer-review started: June 10, 2022

First decision: June 27, 2022

Revised: July 8, 2022

Accepted: August 23, 2022

Article in press: August 23, 2022

Published online: October 26, 2022

Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) of bone marrow is uncommon. Here, we report a case of bone marrow metastatic NEC with an unknown primary site.

A 73-year-old Chinese woman was admitted to our hospital because marked chest distress and asthma lasting 1 d on March 18, 2018. She was initially diagnosed wi

Bone marrow invasion of NEC is rare and our patient who suffered from bone marrow metastatic NEC as well as secondary BMN and MF had an extremely poor prognosis. Bone marrow biopsy plays an important role in the diagnosis of solid tumors invading bone marrow.

Core Tip: Neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) rarely occurs in the bone marrow. We report a patient diagnosed with bone marrow metastatic NEC, bone marrow necrosis and secondary myelofibrosis. As extensive imaging examinations did not show the primary lesion, we speculated that the primary tumor might regress spontaneously or merely not be identified due to lack of positron emission tomography with gallium peptide. Because of the poor general physical condition with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 3-4, chemotherapy was abandoned, and everolimus as well as the best supportive therapies were given. Unfortunately, the patient’s condition continued to deteriorate and finally passed away.

- Citation: Shi XB, Deng WX, Jin FX. Bone marrow metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma with unknown primary site: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(30): 11074-11081

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i30/11074.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i30.11074

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs), account for 0.5% of all malignancies, they originate from neuroendocrine cells throughout the body, and are a group of relatively rare and highly heterogeneous neoplasms[1]. Most NENs occur in the gastrointestinal tract (62%-67%) and the lung (22%-27%)[2]. NENs are divided into well differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs)[2]. The clinical manifestations of NENs mainly depend on whether they are functional or non-functional and which hormones are secreted[3]. Bone marrow metastasis of NENs is extremely rare. Few studies on this topic have been published since 2000 and most of them are case reports[4-14]. We report a case of bone marrow metastatic NEC accompanied by bone marrow necrosis (BMN) and secondary myelofibrosis (MF). In this patient, no neoplastic lesions were found in the body except the bone marrow.

On March 21, 2018, a 73-year-old woman was admitted to the Department of Hematology and Oncology, Tongling People’s Hospital (Anhui Province, China) due to severe unexplained anemia and thrombocytopenia.

Initially, the patient was hospitalized in the emergency ward of internal medicine because of marked chest distress and asthma lasting 1 day on March 18, 2018. The concentrations of B-type natriuretic peptide, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and procalcitonin were 853.90 pg/mL, 140.96 mg/L and 1.51 μg/L, respectively. Peripheral blood count showed a leukocyte count of 12.95 × 109/L, hemoglobin of 29 g/L, platelet count of 49 × 109/L and neutrophil count of 9.84 × 109/L. Chest computed tomography (CT) examination indicated bilateral pulmonary inflammation. The patient was preliminarily diagnosed with pulmonary infection, cardiac insufficiency, thrombocytopenia and severe anemia. She was treated with antibiotic therapy, diuresis and red blood cell transfusions. Following the above treatment, the symptoms of chest tightness and asthma were relieved. The etiology of anemia and thrombocytopenia was unknown, and the patient was hospitalized in our department for further hematological examinations.

The patient did not have a previous history of surgery, anemia or malignant neoplasms and was not taking any medication.

She never smoked and her spouse and daughter were both healthy. Her family history of hematological malignancies and solid tumors was unremarkable.

Physical examination revealed anemia, scattered dry rales in both lungs, a few moist rales in the middle and lower lobe of the right lung and bilateral depressed edema of the lower limbs.

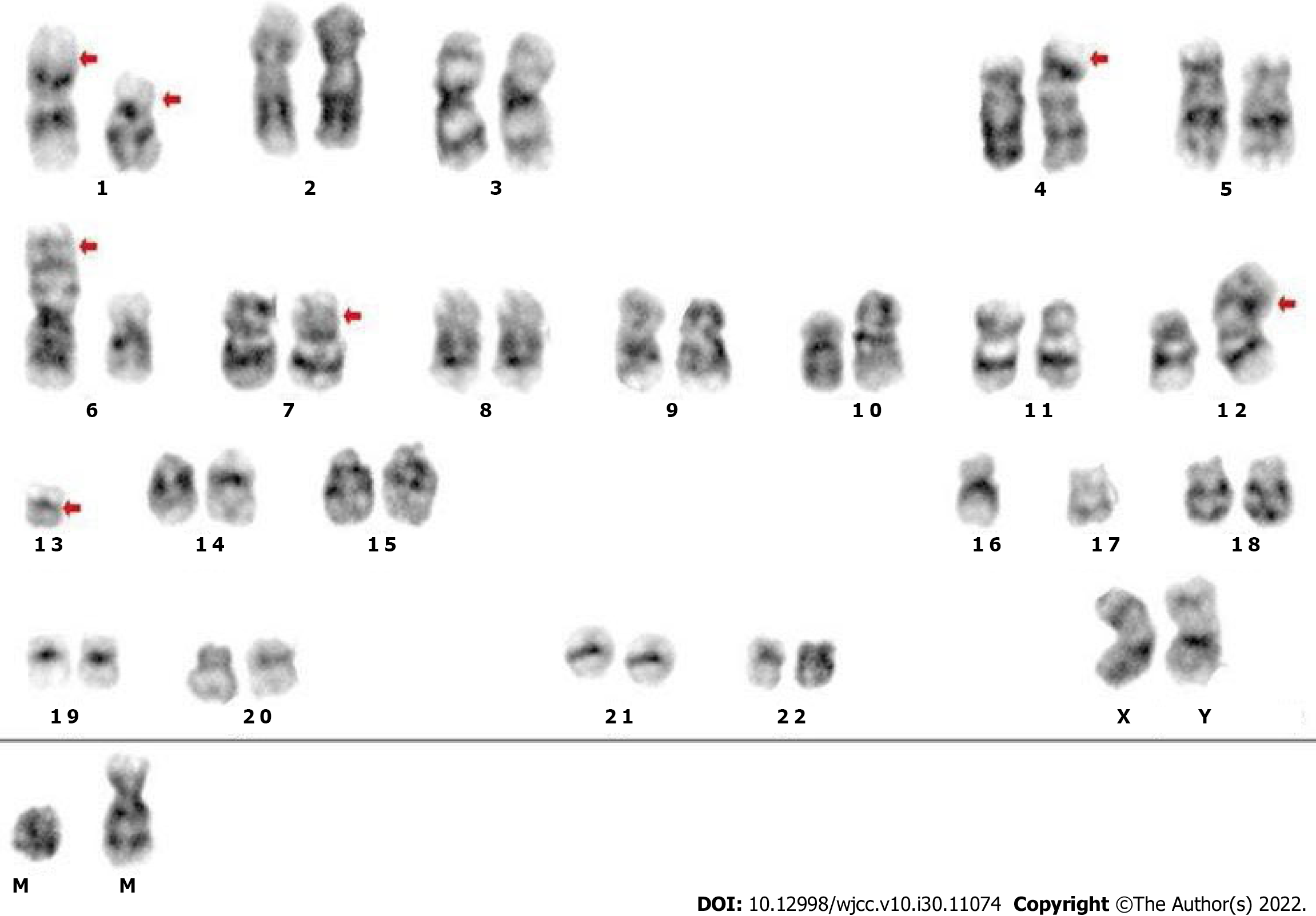

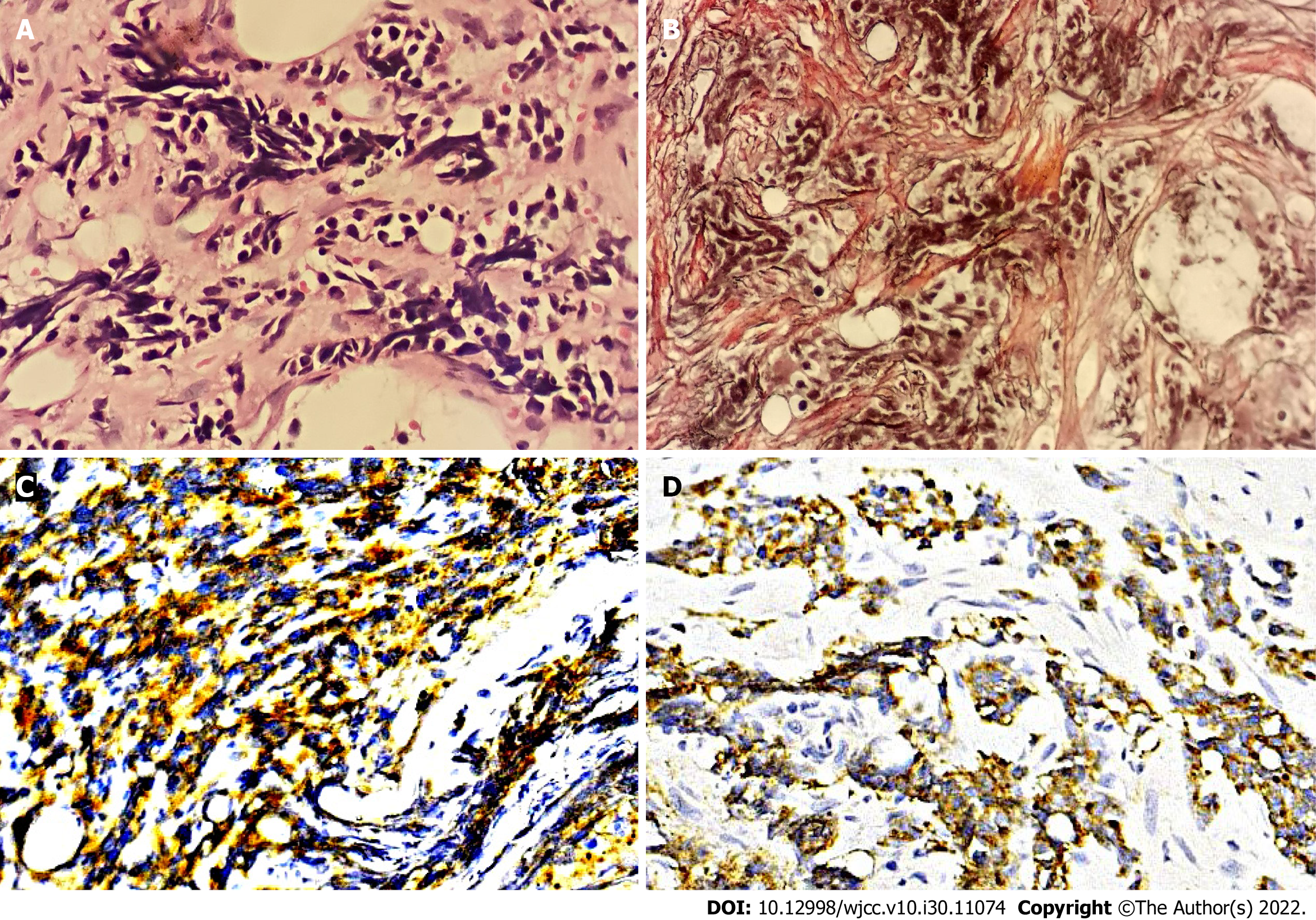

The results of laboratory examinations with the exception of bone marrow tests are listed in Table 1. Both bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were carried out on the right posterior superior iliac spine. Bone marrow cytomorphologic examination revealed that most of the nucleated cells were dissolved and one type of cell characterized by small size, less cytoplasm, no granules in the cytoplasm, a round or irregular nucleus, loose chromatin and distinct nucleoli was discovered. Cytogenetic analysis using both the G-banding and R-banding technique demonstrated a karyotype of 45, XX, del (1) (p13p36.1), I (1) (p10), dup (4) (p15p16), add (6) (p23), der (6) del (6) (p21) del (6) (q23q25), der (7) t (7;11) (p10; q10), add (11) (p11.2), der (12) t (4;12) (q21;p11.2), -13, del (13) (q14), -16, -17, + mar1, + mar2 in 19/20 metaphases examined (Figure 1). Bone marrow biopsy showed that the marrow was characterized by extensive fibrosis and necrosis, moreover, nest-like distributions of small cells with less cytoplasm, round or irregular nuclei and coarse granular and dark stained chromatin were found in the stroma (Figure 2A). Additional immunohistochemistry of this specific category of cells exhibited CD56 (+) (Figure 2C), synaptophysin(+) (Figure 2D), Ki-67 (90% +), CK-pan (scattered and weak +), chromogranin A (-), S-100 (-), TdT (-), CD3 (-), CD5 (-), CD10 (-), CD19 (-), CD34 (-), TTF-1 (-), vimentin (-), and CD117 (-). Reticulin staining was positive (+++) (Figure 2B) and no Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) mutations were detected.

| Testing items | Results |

| Reexamined peripheral blood count | Leukocyte 14.87 × 109/L, hemoglobin 65 g/L; platelet 20 × 109/L and neutrophil 12.46 × 109/L |

| Peripheral blood smear | 2% promyelocyte |

| Coombs test | Negative |

| LDH | 1185 U/L |

| ALP | 355 U/L |

| Coagulation function | Fibrinogen 1.09 g/L, D-dimer >20000 μg/L |

| Serum tumor markers | Carbohydrate antigen 125 236.40 U/mL, ferroprotein > 3000 ng/mL |

Extensive imaging workup including abdominal CT and 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT tumor metabolic imaging did not show the primary lesion (Figure 3).

The patient was diagnosed with bone marrow metastatic NEC with unknown primary site, BMN and secondary MF.

The patient continued treatment with anti-infection medication, blood transfusion, diuresis as well as interleukin-11 after admission to our department. She was subsequently diagnosed with bone marrow metastatic NEC according to bone marrow biopsy and immunohistochemistry. In view of the patient’s poor general physical condition with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 3-4, chemotherapy was abandoned and everolimus (10 mg/d) was added to the treatment on April 26, 2018.

Following supportive and symptomatic therapies, chest tightness and asthma improved. Hemoglobin was maintained above 60 g/L and platelets were maintained between 20 × 109/L and 30 × 109/L. The white blood cell count decreased with the lowest leukocyte count of 2.24 × 109/L and neutrophil count of 1.15 × 109/L following administration of everolimus. Unfortunately, during the treatment process, the patient became more and more emaciated and received repeated albumin infusions due to a significant decline in serum albumin level. Despite being treated with everolimus plus the best supportive treatment, the patient’s condition continued to deteriorate and she died on May 15, 2018.

Although NEN is an uncommon malignant tumor, the incidence of NEN has gradually increased over the past decades owing to continuous improvement in diagnostic methods and improved awareness of the disease[2,15]. The most common site of metastasis in NENs is the liver (40%-93%) followed by bone (12%-20%) and lung (10.8%)[16]. Metastatic NEN in bone marrow is extremely rare and most reported cases are NECs[4-8,11,12].

The main treatments in reported cases of bone marrow metastatic NECs consist of chemotherapy, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) and supportive care. Helbig et al[4] and Post et al[5] respectively reported a NEC patient with multiple metastases with bone marrow invasion. Both the patients received multiple cycles of chemotherapy; however, no effect was observed[4,5]. Another bone marrow metastatic NEC case was offered best supportive care; however, the patient died 2 wk after diagnosis[8]. PRRT is recommended in advanced NEN patients with positive somatostatin receptors (SSTRs)[7]. After four cycles of PRRT with 177Lu-DOTA octreotate, a patient suffering from duodenal NEC with extensive metastases including bone marrow achieved a partial response and a progression-free survival (PFS) of 27 mo[6,7].

Multiple studies have indicated that the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway participates in the development of NENs and mTOR is expected to become a promising therapeutic target for NENs[17]. The clinical trials RADIANT-2 and RADIANT-4 revealed that advanced NEN patients might benefit from the mTOR inhibitor everolimus and achieve a longer median PFS[18,19].

Spontaneous regression (SR), an extremely rare phenomenon, is defined as the partial or complete disappearance of a tumor without any treatment[20]. The burned-out tumors represent tumors presenting SR followed by metastases[21,22]. With regard to NENs, SR of the tumor has been reported in Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), bile duct NET, and both lung and gastric large-cell NECs[23-26]. Longo et al[27] reported a case of inguinal lymphadenopathy histologically corresponding to MCC. The lesion later spontaneously regressed and histopathological examination showed negative results. However, five months later, a nearby lymphadenopathy appeared which was diagnosed as MCC metastasis. Our patient was diagnosed with bone marrow metastatic NEC and further imaging examinations showed no other neoplastic lesions in the body. Similarly, Helbig et al[4] and Schlette et al[13] also reported 2 cases of bone marrow metastatic NENs without primary sites. We hypothesize that the primary tumors of such NENs which can be called burned-out tumors may be located in the gastrointestinal system, pancreas, lung or bile duct and develop SR in order to originate metastases. Furthermore, we did not perform PET with gallium peptide, which may have resulted in potential bias in our diagnosis. Therefore it should be taken into account that the unknown primary lesion was unexplored.

BMN is a relatively rare clinicopathological entity and most common in malignant tumors (80%-90%)[28-30]. Anemia (91%) and thrombocytopenia (78%) are the most frequent hematologic abnormalities in BMN and almost 50% of BMN patients have elevated lactate dehydrogenase and alkaline phosphatase levels[28]. It is reported that 30% of BMN cases are found in solid tumors[28]. As previously mentioned, a patient with BMN caused by a thymic NET died 2 wk after diagnosis[8], and another case of BMN secondary to gastric cancer passed away shortly after hospitalization[31]. Thus, the prognosis of patients suffering from solid tumors with BMN is significantly worse than that of patients with malignancies alone.

MF represents increased fibers in the bone marrow stroma and is usually caused by numerous reactive and neoplastic disorders. There are two types of MF: Primary and secondary. The former is often characterized by splenomegaly and mutations of JAK2, MPL or CALR. Our patient had no splenomegaly or mutations of the above genes, thereby excluding primary MF and the patient’s MF was due to bone marrow metastatic NEC. Secondary MF is very common in patients with bone marrow metastatic tumors. Xiao et al[32] reported that all 101 patients with bone marrow metastatic malig

We report a case of bone marrow metastatic NEC with an unknown primary lesion accompanied by secondary BMN and MF. To our knowledge, few such cases have been reported in China to date. As the patient’s condition was very poor, chemotherapy was ultimately discontinued. According to published reports, NEC patients with multiple metastases including bone marrow infiltration may benefit from treatment with PRRT[6,7]. However, very few hospitals in China can carry out PRRT at present and our hospital is unable to implement SSTR detection and PRRT treatment; thus, we unfortunately failed to attempt PRRT in this patient. On the basis of relevant reports[18,19], the patient received everolimus treatment; however, the patient’s condition did not improve and she died 2 mo after admission.

Bone marrow metastasis of NENs is rare and patients suffering from bone marrow metastatic NEC as well as secondary BMN and MF may have an extremely poor prognosis. Bone marrow biopsy plays an important role not only in the diagnosis of hematological diseases, but also in the diagnosis of solid tumors invading bone marrow.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Debaibi M, Tunisia; Sheikh Hassan M, Somalia; Zhang X, United States S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Ambrosini V, Zanoni L, Filice A, Lamberti G, Argalia G, Fortunati E, Campana D, Versari A, Fanti S. Radiolabeled Somatostatin Analogues for Diagnosis and Treatment of Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Oronsky B, Ma PC, Morgensztern D, Carter CA. Nothing But NET: A Review of Neuroendocrine Tumors and Carcinomas. Neoplasia. 2017;19:991-1002. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 392] [Article Influence: 56.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Metz DC, Jensen RT. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1469-1492. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 601] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 501] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Helbig G, Straczyńska-Niemiec A, Szewczyk I, Nowicka E, Bierzyńska-Macyszyn G, Kyrcz-Krzemień S. Unexpected cause of anemia: metastasis of neuroendocrine tumor to the bone marrow. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2014;124:635-636. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Post GR, Lewis JA, Hudspeth MP, Caplan MJ, Lazarchick J. Disseminated neuroendocrine carcinoma in a pediatric patient: a rare case and diagnostic challenge. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:200-203. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Basu S, Abhyankar A. The use of 99mTc-HYNIC-TOC and 18F-FDG PET/CT in the evaluation of duodenal neuroendocrine tumor with atypical and extensive metastasis responding dramatically to a single fraction of PRRT with 177Lu-DOTATATE. J Nucl Med Technol. 2014;42:296-298. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Basu S, Ranade R, Thapa P. Metastatic Neuroendocrine Tumor with Extensive Bone Marrow Involvement at Diagnosis: Evaluation of Response and Hematological Toxicity Profile of PRRT with (177)Lu-DOTATATE. World J Nucl Med. 2016;15:38-43. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ducourneau B, Hemar C. Bone marrow necrosis in neuroendocrine tumor of the thymus. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6:1970-1971. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Oo TH, Aish LS, Schneider D, Hassoun H. Carcinoid tumor presenting with bone marrow metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2995-2996. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lim KH, Huang MJ, Yang S, Hsieh RK, Lin J. Primary carcinoid tumor of prostate presenting with bone marrow metastases. Urology. 2005;65:174. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kobrinski DA, Choudhury AM, Shah RP. A case of locally-advanced Merkel cell carcinoma progressing with disseminated bone marrow metastases. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28:550-551. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Salathiel I, Wang C. Bone marrow infiltrate by a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199:483-6; discussion 487. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Schlette E, Medeiros LJ, Beran M, Bueso-Ramos CE. Indolent neuroendocrine tumor involving the bone marrow. A case report with a 9-year follow-up. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:488-491. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nakano S, Minaga K, Tani Y, Tonomura K, Hanawa Y, Morimura H, Terashita T, Matsumoto H, Iwagami H, Nakatani Y, Akamatsu T, Uenoyama Y, Maeda C, Ono K, Watanabe T, Yamashita Y. Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Carcinoma with Thrombocytopenia due to Diffuse Bone Marrow and Splenic Infiltration: An Autopsy Case. Intern Med. 2022;. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Deutsch GB, Lee JH, Bilchik AJ. Long-Term Survival with Long-Acting Somatostatin Analogues Plus Aggressive Cytoreductive Surgery in Patients with Metastatic Neuroendocrine Carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:26-36. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Stelwagen J, de Vries EGE, Walenkamp AME. Current Treatment Strategies and Future Directions for Extrapulmonary Neuroendocrine Carcinomas: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:759-770. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chan J, Kulke M. Targeting the mTOR signaling pathway in neuroendocrine tumors. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2014;15:365-379. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pavel ME, Hainsworth JD, Baudin E, Peeters M, Hörsch D, Winkler RE, Klimovsky J, Lebwohl D, Jehl V, Wolin EM, Öberg K, Van Cutsem E, Yao JC; RADIANT-2 Study Group. Everolimus plus octreotide long-acting repeatable for the treatment of advanced neuroendocrine tumours associated with carcinoid syndrome (RADIANT-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2011;378:2005-2012. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 740] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 710] [Article Influence: 54.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yao JC, Fazio N, Singh S, Buzzoni R, Carnaghi C, Wolin E, Tomasek J, Raderer M, Lahner H, Voi M, Pacaud LB, Rouyrre N, Sachs C, Valle JW, Fave GD, Van Cutsem E, Tesselaar M, Shimada Y, Oh DY, Strosberg J, Kulke MH, Pavel ME; RAD001 in Advanced Neuroendocrine Tumours, Fourth Trial (RADIANT-4) Study Group. Everolimus for the treatment of advanced, non-functional neuroendocrine tumours of the lung or gastrointestinal tract (RADIANT-4): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2016;387:968-977. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 749] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 781] [Article Influence: 97.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cole WH. Efforts to explain spontaneous regression of cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:201-209. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 212] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Challis GB, Stam HJ. The spontaneous regression of cancer. A review of cases from 1900 to 1987. Acta Oncol. 1990;29:545-550. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 250] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dorantes-Heredia R, Motola-Kuba D, Murphy-Sanchez C, Izquierdo-Tolosa CD, Ruiz-Morales JM. Spontaneous regression as a 'burned-out' non-seminomatous testicular germ cell tumor: a case report and literature review. J Surg Case Rep. 2019;2019:rjy358. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nijjar Y, Bigras G, Tai P, Joseph K. Spontaneous Regression of Merkel Cell Carcinoma of the Male Breast with Ongoing Immune Response. Cureus. 2018;10:e3589. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sano I, Kuwatani M, Sugiura R, Kato S, Kawakubo K, Ueno T, Nakanishi Y, Mitsuhashi T, Hirata H, Haba S, Hirano S, Sakamoto N. Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic: A rare case of a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor in the bile duct with spontaneous regression diagnosed by EUS-FNA. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:11. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tomizawa K, Suda K, Takemoto T, Iwasaki T, Sakaguchi M, Kuwano H, Mitsudomi T. Progression after spontaneous regression in lung large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: Report of a curative resection. Thorac Cancer. 2015;6:655-658. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ip YT, Pong WM, Kao SS, Chan JK. Spontaneous complete regression of gastric large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: mediated by cytomegalovirus-induced cross-autoimmunity? Int J Surg Pathol. 2011;19:355-358. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Longo R, Balasanu O, Chastenet de Castaing M, Chatelain E, Yacoubi M, Campitiello M, Marcon N, Plastino F. A Spontaneous Regression of an Isolated Lymph Node Metastasis from a Primary Unknown Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Patient with an Idiopathic Hyper-Eosinophilic Syndrome. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:1437-1440. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Janssens AM, Offner FC, Van Hove WZ. Bone marrow necrosis. Cancer. 2000;88:1769-1780. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Coscia L, Causa P, Giuliani E, Nunziata A. Pharmacological properties of new neuroleptic compounds. Arzneimittelforschung. 1975;25:1436-1442. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Paydas S, Ergin M, Baslamisli F, Yavuz S, Zorludemir S, Sahin B, Bolat FA. Bone marrow necrosis: clinicopathologic analysis of 20 cases and review of the literature. Am J Hematol. 2002;70:300-305. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 108] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gérard J, Berdin B, Portier G, Godon A, Tessier-Marteau A, Geneviève F, Zandecki M. [Bone marrow necrosis in two patients with neoplastic disorders]. Ann Biol Clin (Paris). 2007;65:636-642. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Xiao L, Luxi S, Ying T, Yizhi L, Lingyun W, Quan P. Diagnosis of unknown nonhematological tumors by bone marrow biopsy: a retrospective analysis of 10,112 samples. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:687-693. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Guan P, Chen Z, Zhang L, Pan L. Dilemmas in a pregnant woman with myelofibrosis secondary to signet ring adenocarcinoma: a case report. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:679. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |