Published online Jan 21, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i3.882

Peer-review started: February 8, 2021

First decision: March 8, 2021

Revised: March 18, 2021

Accepted: December 22, 2021

Article in press: December 22, 2021

Published online: January 21, 2022

Following the development of the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy, a strict lockdown was imposed from March 9 to May 5, 2020. The risks of self-medication through alcohol or psychoactive substance abuse were increased, as well as the tendency to adopt pathological behaviors, such as gambling and internet addiction.

To evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated containment measures on craving in a group of patients suffering from substance use disorder and/or gambling disorder who were in treatment in outpatient units or in residency programs as inpatients.

One hundred and fifty-three patients completed a structured questionnaire evaluating craving and other behaviors using a visual analogue scale (VAS). Forty-one subjects completed a pencil and paper questionnaire during the interview. The clinician provided an online questionnaire to 112 patients who had virtual assessments due to lockdown restrictions. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica version 8.0. Quantitative parameters are presented as the mean ± SD and qualitative parameters as number and percentage per class. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check for normality of distributions. Analysis of variance and Duncan post hoc test were employed to analyze differences among subgroup means. The associations between variables were measured using Pearson's correlation. A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

The variation in craving between the present and the month before showed VAS-related reductions of craving in 57%, increases in 24%, and no significant change in 19% of the sample. The level of craving was significantly higher (F = 4.36; P < 0.05) in outpatients (n = 97; mean = 3.8 ± 3.1) living in their own home during the quarantine compared with inpatients (n = 56; mean = 2.8 ± 2.8) in residential programs. Craving for tetrahydrocannabinol was the greatest (4.94, P < 0.001) among various preferred substances.

The unexpected result of this study may be explained by a perceived lack of availability of substances and gambling areas and/or decreased social pressure on a subject usually excluded and stigmatized, or the acquisition of a new social identity based on feelings of a shared common danger and fate that oversha

Core Tip: Our data suggest that craving, regardless of whether determined by substances or behaviors, was globally reduced in a period that could be highly stressogenic such as the coronavirus disease-2019 lockdown.

- Citation: Alessi MC, Martinotti G, De Berardis D, Sociali A, Di Natale C, Sepede G, Cheffo DPR, Monti L, Casella P, Pettorruso M, Sensi S, Di Giannantonio M. Craving variations in patients with substance use disorder and gambling during COVID-19 lockdown: The Italian experience. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(3): 882-890

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i3/882.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i3.882

Following the development of the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy, a strict lockdown was imposed from March 9 to May 5, 2020. In the general population, problems such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptoms, insomnia, and adjustment disorder symptoms increased[1]. The risks of self-medication through alcohol or psychoactive substances abuse were also increased, as well as the tendency to adopt pathological behaviors, such as gambling and internet addiction[2,3]. Stressors are essential in the inception and protraction of substance use disorder (SUD). Many stressors are associated with lockdown conditions such as prolonged home confinement, depression and panic related to the disease's uncertainties, working from home, and fear of job loss. People exposed to these stressors may take refuge in addictive substances, increasing SUD incidence among the general population[4] in a post-modern society that is increasingly oriented towards the use of substances, favoring the development of symptoms of psychopathological interest[5]. The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown are risk conditions for developing internet, videogames, or other addiction, decreased physical activity and related health issues, altered eating habits, and disrupted circadian rhythms. King et al[6] and Király et al[7] demonstrated how these behaviors increased during the lockdown, often generated as a coping strategy to stressful situations.

In patients with pre-existing mental disorders, the symptomatology may flare up or worsen, generating increased suicidal ideation as a possible consequence[8-10]. Substance users and gamblers are groups at risk of developing psychopathological symptoms in a lockdown situation. The phenomenon is likely due to various reasons, including: (1) The limited availability of illegal substances on the black market; (2) the insufficient presence of active treatment programs and the low availability of substitute drugs; and (3) the greater psychopathological susceptibility and lower resilience in a period of reduced economic resources and financial hardship[11,12].

In this study, we evaluated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated containment measures on craving, a prominent risk factor for relapse[12] in a group of patients suffering from SUD and/or gambling disorder (GD) who were in treatment in outpatient units or in residency programs as inpatients.

This study was commissioned by the Italian Society of Psychiatry and conducted at the University "Gabriele d'Annunzio" of Chieti-Pescara during the Italian lockdown phase that lasted from March 3 to May 5, 2020. Recruitment centers were randomly chosen among all the structures providing services for SUD and GD patients in regions of Northern (Piemonte, Lombardia), Central (Lazio, Marche), and Southern Italy (Abruzzo, Calabria) (see Appendix A: List of recruitment centers). Randomization procedures were computerized (see Appendix B: Explanation of randomized procedures). Three online meetings were held to train clinicians to the administration of the questionnaire, before the study started. In each recruitment center, a clinician introduced the survey to all the eligible subjects. No compensation was provided for participation in the study. Of the 253 subjects recruited, 153 (mean age 39.8; 77.8% male) gave their consent and anonymously completed the questionnaire. Forty-one subjects completed a pencil and paper questionnaire during the interview. The clinician provided an online questionnaire to 112 patients who had virtual assessments due to lockdown restrictions. Questionnaires were anonymous and each subject was identified through a unique code with no other identifying data. Anonymity was maintained by placing the completed questionnaires in a box by the subject himself, so that the clinician could not associate the subject with his/her questionnaire. All participants provided informed consent. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Diagnosis of SUD or GD according to The Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; and (2) being older than 18 years. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Diagnosis of dementia; and (2) refusal to give informed consent.

Our survey was organized into two sections. In the first section, we collected anamnestic and clinical variables (see Appendix C: List of anamnestic and clinical variables). In the second section, using a visual analogue scale (VAS), we asked the subjects to indicate the craving level for the primary substance of abuse and how much their craving and habits have changed from the beginning of lockdown. We chose to use the VAS because of its immediacy and extensive utilization to evaluate craving in addicted patients[13,14]. We investigated changes of: (1) Craving for substances and gambling; and (2) quality of life and life habits (Table 1). A VAS ranging from 0 (I do not use it/I do not do this anymore) to 10 (I use it/I do this much more than before) was employed. To assess changes in quality of life, we utilized a VAS ranging from 0 (my life is much worse than before) to 10 (my life is much better than before) (see Appendix D: Questionnaire).

| Substance/pathological behavior | n | % |

| Cocaine | 66 | 43.1 |

| Alcohol | 39 | 25.5 |

| THC | 24 | 15.7 |

| Gambling | 12 | 7.9 |

| Heroin | 9 | 5.7 |

| Ketamine | 1 | 0.7 |

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica version 8.0. Quantitative parameters are presented as the mean ± SD and qualitative parameters as number and percentage per class. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check for normality of distributions. Analysis of variance and Duncan post hoc test were employed to analyze differences among subgroup means. The associations between variables were measured using Pearson's correlation. A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Among 153 subjects that completed the questionnaire, the primary substances of abuse or pathological behavior are reported in Table 1.

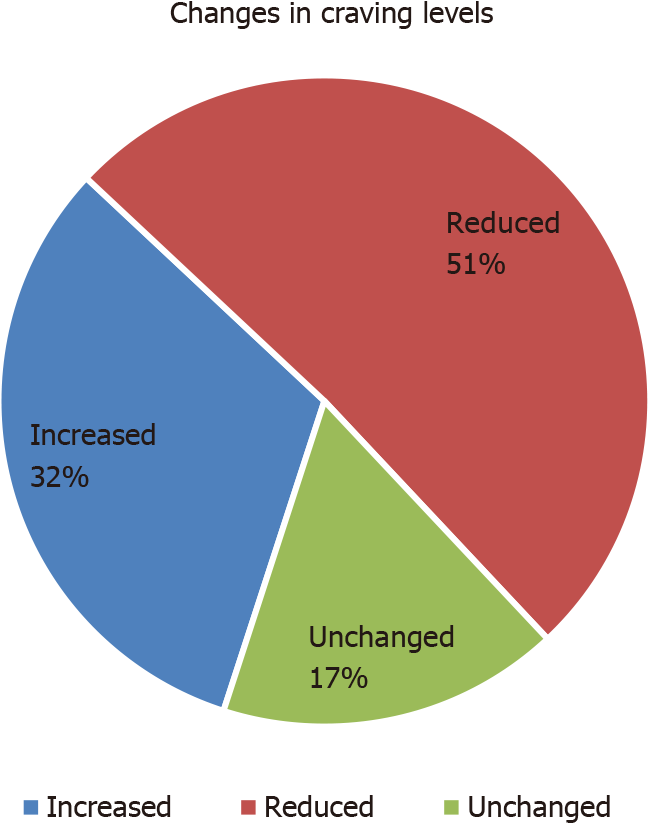

Sixty-seven (43.8%) of the participants reported a comorbid psychiatric condition, especially mood disorders (depression, bipolar disorder) and anxiety. In this subsample, a psychopharmacological treatment was reported by 94% of subjects. The variation in craving between the present and the month before showed VAS-related reductions of craving in 57%, increases in 24%, and no significant change in 19% of the sample (Figure 1).

The level of craving was significantly higher (F = 4.36; P < 0.05) in outpatients (n = 97; mean = 3.8 ± 3.1) living in their own home during the quarantine compared with inpatients (n = 56; mean = 2.8 ± 2.8) in residential programs. Craving for tetrahydrocannabinol was the greatest (4.94, P < 0.001) among various preferred substances (Figure 2).

Patients with a dual diagnosis (n = 67; mean craving VAS = 3.9) did not show a significant difference in the levels of craving [F (1; 150) = 2.43, P > 0.121] with respect to patients without psychiatric comorbidities (n = 86; mean craving VAS = 3.1).

Overall, we observed an increased consumption of coffee and cigarettes in about half of the sample. In contrast, symptoms indicative of behavioral addictions and other substances' consumption remained almost stable (Table 2). Changes in life habits are shown in Table 2. Reduced quality of life due to COVID-19 driven by the lockdown was present in 51% of the patients; 25.5% declared no significant changes, and, surprisingly, 23.5% increased quality of life. Low levels of quality of life correlated with high craving scores (r = -0.226, P = 0.005).

| Reduced | Unchanged | Increased | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Changes in consumption habits | ||||||

| Alcohol | 22 | 14.4 | 103 | 67.3 | 28 | 18.3 |

| Coffee | 10 | 6.5 | 78 | 51.0 | 65 | 42.5 |

| Cigarettes | 7 | 4.6 | 75 | 49.0 | 71 | 46.4 |

| Cannabis | 22 | 14.4 | 118 | 77.1 | 13 | 8.5 |

| Cocaine | 24 | 15.7 | 122 | 79.7 | 7 | 4.6 |

| Opioids | 7 | 4.6 | 143 | 93.5 | 2 | 1.3 |

| Benzodiazepines and similar medical drugs | 7 | 4.6 | 120 | 78.4 | 25 | 16.3 |

| Gambling offline | 14 | 9.2 | 132 | 86.3 | 6 | 3.9 |

| Gambling online | 12 | 7.8 | 133 | 86.9 | 7 | 4.6 |

| Shopping online | 7 | 4.6 | 123 | 80.4 | 19 | 12.4 |

| Eating | 10 | 6.5 | 65 | 42.5 | 77 | 50.3 |

| Videogames | 8 | 5.2 | 115 | 75.2 | 29 | 19.0 |

| Changes in time spent for the following activities | ||||||

| Instant messaging with friends and relatives | 6 | 3.9 | 66 | 43.1 | 79 | 51.6 |

| Social network (for fun, reading) | 7 | 4.6 | 72 | 47.1 | 73 | 47.7 |

| Video calls with friends and relatives | 8 | 5.2 | 60 | 39.2 | 84 | 54.9 |

| Collecting online information about the current situation | 9 | 5.9 | 81 | 52.9 | 62 | 40.5 |

| Old and new hobbies | 14 | 9.2 | 75 | 49.0 | 63 | 41.2 |

| Sports | 30 | 19.6 | 74 | 48.4 | 48 | 31.4 |

| Watching movies, TV shows | 9 | 5.9 | 51 | 33.3 | 92 | 60.1 |

| Watching pornographic material | 12 | 7.8 | 108 | 70.6 | 32 | 20.9 |

| Hours of sleep each day | 27 | 17.6 | 42 | 27.5 | 83 | 54.2 |

In this study, the recruited group of patients with a diagnosis of SUD represents a real-life sample that reflects the Italian addiction scenario, including patients known by local services of seven different representative Italian regions. The evaluation of craving scores during the first phases of the COVID pandemic represents a relevant point, given the presence in that period of strict lockdown restrictions. Although other studies evaluated the psychopathological burden of alcohol and substance users during the strict lockdown[15,16], the specific evaluation of craving represents a novel and relevant aspect, given the crucial role of craving in treatment strategies. Different studies[17,18] have proposed that, together with negative affect states, cognitive factors, interpersonal problems, and lack of coping, craving is one of the leading risk factors for relapse[19]. Our data suggest that craving, regardless of whether determined by substances or behaviors, was globally reduced in a period that could be highly stressogenic. This data was unexpected, and is in contrast with other studies reporting increased levels of anxiety, depression, and psychotic symptoms during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic[20,21]. Moreover, in alcohol and substance users, other detrimental factors can act synergistically during the pandemic period: Psychological discomfort from social isolation, restricted freedom, and a quantitative and qualitative reduction in the addiction services’ assistance and in the stretching of their service.

In order to explain this controversial data, we propose the hypothesis of a perceived lack of availability of substances and gambling areas. Practical difficulties in sources of supply, such as the unavailability of the usual dealing spaces, may have interrupted the development of the craving priming. Craving is usually determined by the possibility to obtain a substance. When external measures limit this possibility, craving itself could be dramatically reduced, as the case of the strict lockdown. Second, we hypothesize the presence of decreased social pressure on a group of subjects who are usually excluded and stigmatized. Social exclusion is indeed a psychosocial stress factor[22] that can increase craving and drug use[23]. As social identification is the self-definition of a person in terms of group membership[10], the period of lockdown because of the COVID-19 pandemic can favor personal feelings of being part of a group facing a common danger and sharing a common fate. Therefore, this new social identity might overshadow the sense of exclusion and rejection in the abuser, ultimately with the positive outcome of reducing craving and substance abuse. This possibility is consistent with data from a survey released by the Israel Democracy Institute that showed how the sense of belonging and unity increased during the COVID-19 outbreak among groups usually sidelined[24]. In this direction, the use of a specific strategy such as telepsychiatry acquires great importance for careful monitoring of the patient’s clinical and psychopathological conditions, in order to prevent relapses and to promote social integration[25].

Our data also indicates that residential treatment in containment facilities during the quarantine is an effective procedure that positively impacts craving levels, probably reinforcing the first hypothesis regarding the unavailability of the substance as a means to reduce craving.

In line with other studies, our data showed an increase in the consumption of coffee and cigarettes. Increased cigarette use could be explained as a natural response to stressful events, especially as a consequence of depressive symptoms; the consumption of coffee could be determined by the tendency towards sugary foods and drinks, in order to find quick relief in stressful times[26,27].

It is also interesting to note that a relevant part of the sample reported reduced quality of life during the strict lockdown, with a negative correlation between craving and perceived quality of life. This data leads us to hypothesize that despite a substantial reduction in the perceived quality of life, the levels of craving have in any case been reduced, as a counter-proof of how much the unavailability of the substance and the increase in social integration may have had a direct positive effect on the reduction of craving.

The main limitation of our study is the high prevalence of cocaine abusers. This demographic feature is different from other treatment-seeking cohorts where alcohol is generally the main substance of abuse. This discrepancy is probably because our recruitment centers are specialized in the treatment of cocaine use disorder. Another limitation of the study is the use of a VAS instead of validated scales. We chose to use VAS because of its immediacy to homogenize and accelerate the completion of the questionnaire, making it suitable also online during the virtual assessments due to lockdown restrictions. Our results are difficult to generalize because of the brief time of observation, and further studies are needed.

Our data suggest that craving was globally reduced in a period that could be highly stressogenic. This unexpected result may be explained by: (1) A perceived lack of availability of substances and gambling areas that interrupted the development of the craving priming; and (2) the presence of a decreased social pressure. Our results can lay the groundwork for future treatment policies in the direction of strategies that limit the availability of the substance and in parallel towards strategies that aim at greater social integration of subjects affected by addiction disorders.

Following the development of the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy, a strict lockdown was imposed from March 9 to May 5, 2020. In the general population, problems such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptoms, insomnia, and adjustment disorder symptoms increased. The risks of self-medication through alcohol or psychoactive substances abuse were also increased, as well as the tendency to adopt pathological behaviors, such as gambling and internet addiction.

Substance users and gamblers are groups at risk of developing psychopathological symptoms in a lockdown situation. The phenomenon is likely due to various reasons, including: (1) The limited availability of illegal substances on the black market; (2) the insufficient presence of active treatment programs and the low availability of substitute drugs; and (3) the greater psychopathological susceptibility and lower resilience in a period of reduced economic resources and financial hardship.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated containment measures on craving in a group of patients suffering from SUD and/or gambling disorder (GD) who were in treatment in outpatient units or in residency programs as inpatients.

In this cross-sectional study, 153 patients completed a structured questionnaire evaluating craving and other behaviors using a visual analogue scale (VAS). In each recruitment center, a clinician introduced the survey to all the eligible subjects. No compensation was provided for participation in the study. Of the 253 subjects recruited, 153 (mean age 39.8; 77.8% male) gave their consent and anonymously completed the questionnaire. Forty-one subjects completed a pencil and paper questionnaire during the interview. The clinician provided an online questionnaire to112 patients who had virtual assessments due to lockdown restrictions. Questionnaires were anonymous and each subject was identified through a unique code with no other identifying data. Anonymity was maintained by placing the completed questionnaires in a box by the subject himself, so that the clinician could not associate the subject with his/her questionnaire. All participants provided informed consent. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Diagnosis of SUD or GD according to The Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; and (2) being older than 18 years. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Diagnosis of dementia; and (2) refusal to give informed consent.

Sixty-seven (43.8%) of the participants reported a comorbid psychiatric condition, especially mood disorders (depression, bipolar disorder) and anxiety. In this subsample, a psychopharmacological treatment was reported by 94% of subjects. The variation in craving between the present and the month before showed VAS-related reductions of craving in 57%, increases in 24%, and no significant change in 19% of the sample. The level of craving was significantly higher (F = 4.36; P < 0.05) in outpatients (n = 97; mean = 3.8 ± 3.1) living in their own home during the quarantine compared with inpatients (n = 56; mean = 2.8 ± 2.8) in residential programs. Craving for tetrahydrocannabinol was the greatest (4.94, P < 0.001) among various preferred substances. Patients with a dual diagnosis did not show a significant difference in the levels of craving [F (1; 150) = 2.43, P > 0.121] with respect to patients without psychiatric comorbidities (n = 86; mean craving VAS = 3.1). Reduced quality of life due to COVID-19 driven by the lockdown was present in 51% of the patients; 25.5% declared no significant changes, and, surprisingly, 23.5% increased quality of life. Low levels of quality of life correlated with high craving scores (r = -0.226, P = 0.005).

Our data suggest that craving, regardless of whether determined by substances or behaviors, was globally reduced in a period that could be highly stressogenic. This data leads us to hypothesize that despite a substantial reduction in the perceived quality of life, the levels of craving have in any case been reduced, as a counter-proof of how much the unavailability of the substance and the increase in social integration may have had a direct positive effect on the reduction of craving.

Our results can lay the groundwork for future treatment policies in the direction of strategies that limit the availability of the substance and in parallel towards strategies that aim at greater social integration of subjects affected by addiction disorders.

The authors wish to dedicate this manuscript in memory of Dr. Sepede. Her energy and scientific keenness will continue to be a reference model for us. The authors also wish to thank the “CO-dip group” for the help in carrying out the study: Ceci Franca, Lucidi Lorenza, Picutti Elena, Di Carlo Francesco, Corbo Mariangela, Vellante Federica, Fiori Federica, Tourjansky Gaia, Catalano Gabriella, Carenti Maria Luisa, Concetta Incerti Chiara, Bartoletti Luigi, Barlati Stefano, Romeo Vincenzo Maria, and Valchera Alessandro.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Musikanski L S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D, Mensi S, Niolu C, Pacitti F, Di Marco A, Rossi A, Siracusano A, Di Lorenzo G. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. An n = 18147 web-based survey. medRxiv. 2020;. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Vanderbruggen N, Matthys F, Van Laere S, Zeeuws D, Santermans L, Van den Ameele S, Crunelle CL. Self-Reported Alcohol, Tobacco, and Cannabis Use during COVID-19 Lockdown Measures: Results from a Web-Based Survey. Eur Addict Res. 2020;26:309-315. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 240] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ko CH, Yen JY. Impact of COVID-19 on gaming disorder: Monitoring and prevention. J Behav Addict. 2020;9:187-189. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dubey MJ, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Biswas P, Dubey S. COVID-19 and addiction. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:817-823. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 204] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Martinotti G, De Risio L, Vannini C, Schifano F, Pettorruso M, Di Giannantonio M. Substance-related exogenous psychosis: a postmodern syndrome. CNS Spectr. 2021;26:84-91. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | King DL, Delfabbro PH, Billieux J, Potenza MN. Problematic online gaming and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Behav Addict. 2020;9:184-186. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 280] [Article Influence: 70.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Király O, Potenza MN, Stein DJ, King DL, Hodgins DC, Saunders JB, Griffiths MD, Gjoneska B, Billieux J, Brand M, Abbott MW, Chamberlain SR, Corazza O, Burkauskas J, Sales CMD, Montag C, Lochner C, Grünblatt E, Wegmann E, Martinotti G, Lee HK, Rumpf HJ, Castro-Calvo J, Rahimi-Movaghar A, Higuchi S, Menchon JM, Zohar J, Pellegrini L, Walitza S, Fineberg NA, Demetrovics Z. Preventing problematic internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consensus guidance. Compr Psychiatry. 2020;100:152180. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 323] [Article Influence: 80.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Balanzá-Martínez V, Atienza-Carbonell B, Kapczinski F, De Boni RB. Lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 - time to connect. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;141:399-400. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 134] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:510-512. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2488] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2245] [Article Influence: 561.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dingle GA, Stark C, Cruwys T, Best D. Breaking good: breaking ties with social groups may be good for recovery from substance misuse. Br J Soc Psychol. 2015;54:236-254. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 115] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kar SK, Arafat SMY, Sharma P, Dixit A, Marthoenis M, Kabir R. COVID-19 pandemic and addiction: Current problems and future concerns. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102064. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Volkow ND. Collision of the COVID-19 and Addiction Epidemics. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:61-62. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 499] [Article Influence: 124.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kleykamp BA, De Santis M, Dworkin RH, Huhn AS, Kampman KM, Montoya ID, Preston KL, Ramey T, Smith SM, Turk DC, Walsh R, Weiss RD, Strain EC. Craving and opioid use disorder: A scoping review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107639. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Flaudias V, Teisseidre F, De Chazeron I, Chalmeton M, Bertin C, Izaute M, Chakroun-Baggioni N, Pereira B, Brousse G, Maurage P. A multi-dimensional evaluation of craving and impulsivity among people admitted for alcohol-related problems in emergency department. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:569-571. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Martinotti G, Alessi MC, Di Natale C, Sociali A, Ceci F, Lucidi L, Picutti E, Di Carlo F, Corbo M, Vellante F, Fiori F, Tourjansky G, Catalano G, Carenti ML, Incerti CC, Bartoletti L, Barlati S, Romeo VM, Verrastro V, De Giorgio F, Valchera A, Sepede G, Casella P, Pettorruso M, di Giannantonio M. Psychopathological Burden and Quality of Life in Substance Users During the COVID-19 Lockdown Period in Italy. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:572245. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Columb D, Hussain R, O'Gara C. Addiction psychiatry and COVID-19: impact on patients and service provision. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37:164-168. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sinha R, Fox HC, Hong KI, Hansen J, Tuit K, Kreek MJ. Effects of adrenal sensitivity, stress- and cue-induced craving, and anxiety on subsequent alcohol relapse and treatment outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:942-952. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 274] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mahoney JJ 3rd, Kalechstein AD, De La Garza R 2nd, Newton TF. A qualitative and quantitative review of cocaine-induced craving: the phenomenon of priming. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:593-599. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | McKay JR. Studies of factors in relapse to alcohol, drug and nicotine use: a critical review of methodologies and findings. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:566-576. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 95] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | de Sousa Moreira JL, Barbosa SMB, Vieira JG, Chaves NCB, Felix EBG, Feitosa PWG, da Cruz IS, da Silva CGL, Neto MLR. The psychiatric and neuropsychiatric repercussions associated with severe infections of COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;106:110159. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ptacek R, Ptackova H, Martin A, Stefano GB. Psychiatric Manifestations of COVID-19 and Their Social Significance. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e930340. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hanlon CA, Shannon EE, Porrino LJ. Brain activity associated with social exclusion overlaps with drug-related frontal-striatal circuitry in cocaine users: A pilot study. Neurobiol Stress. 2019;10:100137. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sinha R, Fuse T, Aubin LR, O'Malley SS. Psychological stress, drug-related cues and cocaine craving. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2000;152:140-148. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 345] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Staff T. Isolated by pandemic, Israelis have record-high 'sense of 'belonging'. 2020 Apr 26 [cited 8 February 2021]. In: The Times of Israel. Available from: https://www.timesofisrael.com/isolated-by-pandemic-israelis-have-record-high-sense-of-belonging-poll/. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Di Carlo F, Sociali A, Picutti E, Pettorruso M, Vellante F, Verrastro V, Martinotti G, di Giannantonio M. Telepsychiatry and other cutting-edge technologies in COVID-19 pandemic: Bridging the distance in mental health assistance. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 85] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Malta DC, Szwarcwald CL, Barros MBA, Gomes CS, Machado ÍE, Souza Júnior PRB, Romero DE, Lima MG, Damacena GN, Pina MF, Freitas MIF, Werneck AO, Silva DRPD, Azevedo LO, Gracie R. The COVID-19 Pandemic and changes in adult Brazilian lifestyles: a cross-sectional study, 2020. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2020;29:e2020407. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 99] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Karahan Yılmaz S, Eskici G. Evaluation of emotional (depression) and behavioural (nutritional, physical activity and sleep) status of Turkish adults during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24:942-949. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |