Published online Jun 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5331

Peer-review started: July 12, 2021

First decision: September 28, 2021

Revised: October 4, 2021

Accepted: April 20, 2022

Article in press: April 20, 2022

Published online: June 6, 2022

Chordoma is a rare low-grade malignant tumor originating from embryonic notochordal tissue mainly occurring in the axial bone, mostly in the spheno-occipital junction and sacrococcyx, which accounts for approximately 1% of all malignant bone tumors and 0.1%–0.2% of intracranial tumors. Chordoma in the petrous mastoid region is rare.

We describe a 36-year-old male patient with chordoma in the left petrous mastoid region. The main clinical manifestations were pain and discomfort, which lasted for 2 years. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a lobulated mass in the left petrous mastoid with an unclear boundary and obvious enhancement. The tumor was completely removed after surgical treatment, and a histological examination confirmed that the tumor was a chordoma. During 5 years of follow-up, no clinical or radiological evidence of recurrence or metastasis was found.

Chordoma in the petrosal mastoid region is rare but should be included in differential diagnosis of petrosal mastoid tumors.

Core Tip: Chordoma is a rare disease, especially in the petrous mastoid region. Its imaging findings have rarely been reported, and an understanding of its magnetic resonance imaging findings is lacking. However, in the differential diagnosis of petrous mastoid tumors, chordoma should be considered, especially when lobulated masses are found.

- Citation: Hua JJ, Ying ML, Chen ZW, Huang C, Zheng CS, Wang YJ. Chordoma of petrosal mastoid region: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(16): 5331-5336

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i16/5331.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5331

Chordoma is a rare low-grade malignant tumor originating from embryonic notochordal tissue with an incidence of less than 0.1/100000 individuals per year[1]. Chordoma is locally destructive and easily invades important structures, such as bones, nerves, and large blood vessels. Chordoma is likely to relapse after resection, but metastasis is rare. The pathogenesis of chordoma is unclear, and the disease is speculated to originate from residual cells of the notochord that develop during fetal development. The tumor usually occurs in the axial bone, especially at both ends. Most chordomas in the head and neck occur in the spheno-occipital junction, accounting for almost 35% of all chordomas[2]. A few cases occurring in the nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, oropharynx, and jugular foramen have been reported[2,3], and approximately 0.2% of the cases reported in the literature occurred in the jugular foramen region[4] but not the petrosal mastoid region. Here, we report a case of chordoma in the left petrosal mastoid region with intracranial expansive growth resulting in cerebellar compression and deformation. The main clinical manifestation was a 2-year history of temporal pain and discomfort.

A 36-year-old man visited our hospital in December 2014 because of left temporal pain.

In 2012, no obvious cause for his left temporal pain and left-sided headache could be identified, and the patient had no symptoms of hearing loss, dizziness, nausea, or vomiting and no obvious redness, swelling, heat, pain, or structural aberrations in the adjacent skin.

The patient had a history of hepatitis B infection for > 30 years, and his liver function was normal.

No specific genetic or family history of disease was identified.

Neurological examination revealed House Brackmann Grade II, gait disturbance, and tinnitus. The patient denied hearing loss and diplopia.

No abnormality was found in the laboratory examination.

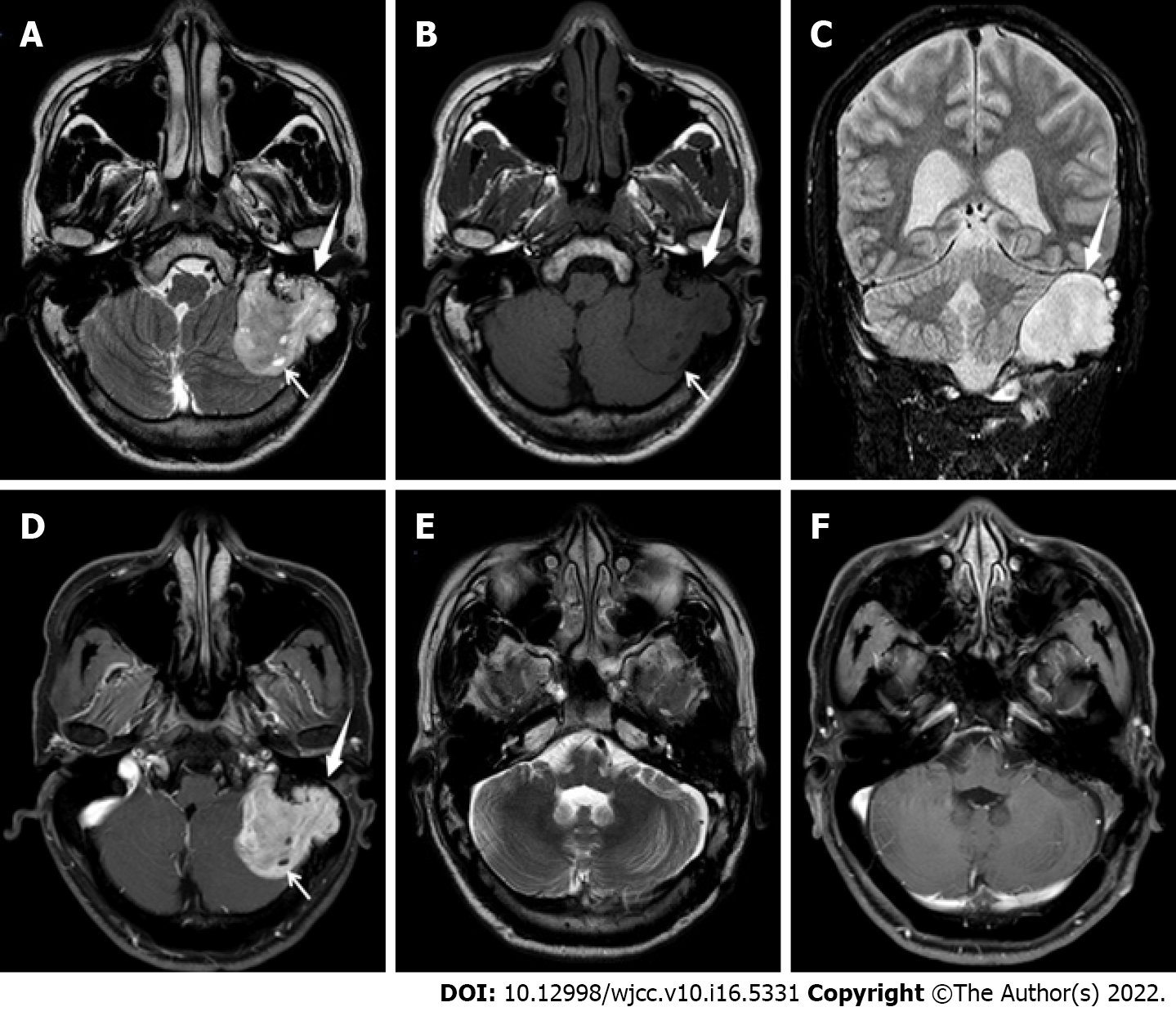

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain a lobulated mass in the left petrous mastoid region with a maximum interface of approximately 3.2 cm × 3.9 cm × 5.0 cm; surrounding bone absorption and destruction; uneven signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) (Figure 1A); isointensity and hypointensity on T1-weighted imaging (Figure 1B); hyperintensity on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (Figure 1C); small cystic degeneration in the interior of the tumor (Figure 1A and B); and obvious enhancement of the solid components of the lesion on the contrast-enhanced scan (Figure 1D). No sign of involvement of the left jugular vein and left sigmoid sinus was observed. Left cerebellar compression and displacement were evident, but no brain parenchymal edema was noted.

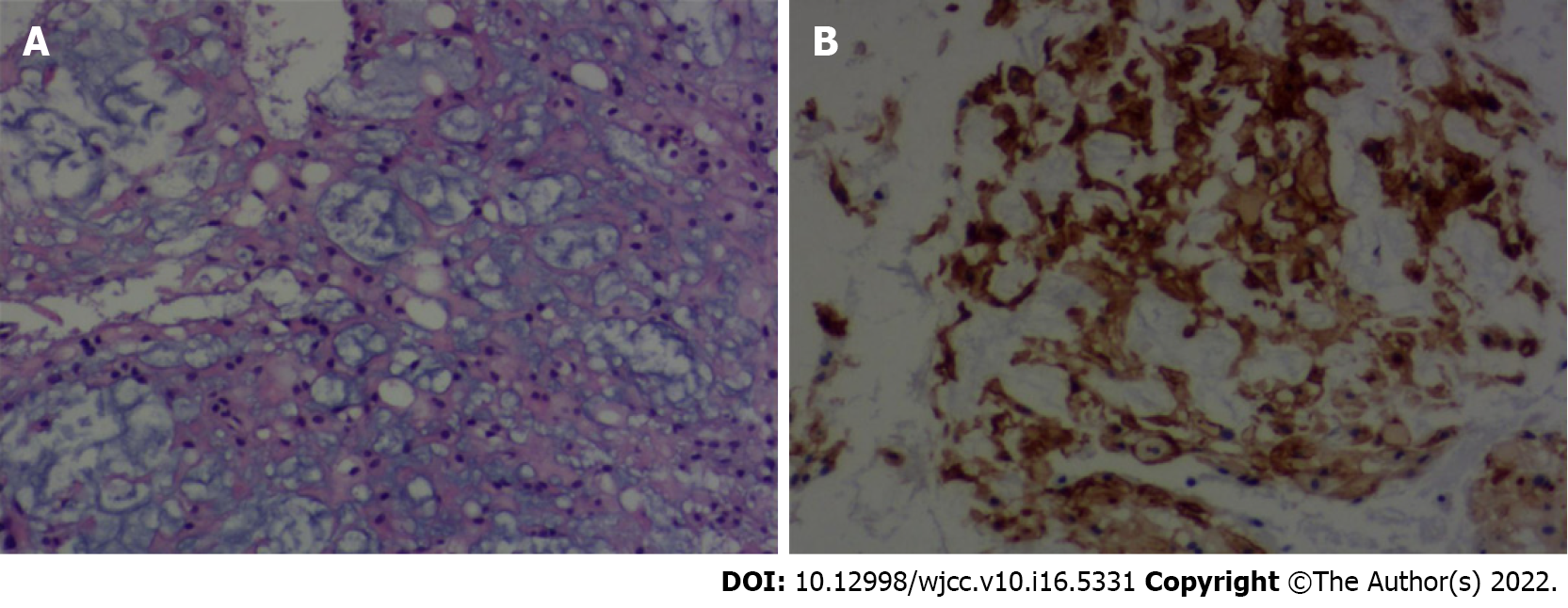

The gross specimen of the tumor was grayish-red and tough with a rich blood supply and had an unclear boundary. Microscopically, the tumor consisted of a dual cell population embedded in an abundant myxoid background. The cells were epithelioid polygonal in appearance with clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm, and a few mitotic cells were observed (Figure 2A). The immunohistochemical staining showed that vimentin, soluble protein-100 (S-100), epithelial membrane antigen (Figure 2B), and cytokeratin (CK)19 were positive, and CK staining was negative. The Ki67 antigen (Ki-67) fraction was approximately 1%. Ultimately, a diagnosis of chordoma was made.

The patient underwent microscopic tumor resection through the upper and posterior windows of the left ear. During the operation, the tumor was found to be located in the epidura; the petrous part of the temporal bone and the surface of the occipital bone were eroded by the tumor; the left transverse sinus was involved; and the lower part of the tumor surrounded the nerves and vessels.

The patient recovered well after surgery, no specific discomfort was mentioned, and he was discharged 1 wk after the operation. As chordoma is a low-grade malignant tumor, the patient was re-examined once a year after the operation, and no obvious abnormality was found after follow-up for 5 years (Figure 1E and F).

Chordoma is a rare, slow-growing, locally invasive malignant tumor originating from primitive notochordal tissues that develop longitudinally along the axis. Chordomas account for 3% of all primary bone tumors[5]. Approximately 50% of chordomas occur in the sacrococcyx, 30% of chordomas occur in the spheno-occipital region, and 20% of chordomas occur in the mobile spine[6]. Chordoma can occur at any age, and the most common age at diagnosis is 20–40 years. The gross specimen of the tumor showed lobulated and expansive growth with mucus, cystic necrosis, a small bleeding focus, calcification, ossification, and cartilage islands, which easily invaded the surrounding bone and caused extensive bone destruction. Histologically, the tumor was composed of droplet cells; the tumor tissue was divided into lobules by connective tissue; and the tumor cells were arranged into small clusters, flakes, strips, and acini with common degeneration and myxoid degeneration in the stroma. Histologically, chordoma appearance can be divided into the following three subtypes: classical, chondroid and dedifferentiated, and classical chordoma is the most common subtype. In addition, chondroid tumor growth is the slowest, and dedifferentiated tumor growth is the fastest.

Typical chordoma computed tomography (CT) findings mainly include: irregular low-density masses with well-defined boundaries; expansive growth, absorption and destruction of surrounding bone; irregular calcification inside the lesion; and obvious enhancement[7]. CT can accurately show bone and internal calcification but is insufficient for soft tissue analyses, and MRI is needed to facilitate further diagnosis.

The MRI findings of chordomas are diverse[8]. The typical MRI findings of chordomas in the clival region show obvious hyperintensity and a “beehive-like” appearance on T2WI, reflecting the histological characteristics of tumor tissue mainly composed of mucous stroma and droplet tumor cells secreting mucus. In this case, the presence of scattered strips and flakes with a low signal intensity suggested that the tumor was related to bone destruction, calcification, or a fibrous septum, and the high signal area in the tumor was separated and appeared beehive-like[9]. Enhancement of the chordoma on imaging is mainly inhomogeneous and obvious, while the dynamic enhancement scan shows continuous and slow enhancement, which is mainly caused by the adsorption of Gd-DTPA molecules to the mucin in the cell or cell interstitium, and the typical enhancement of chordoma shows a “honeycomb sign”[9]. In this case, the MRI findings differed from those of typical chordomas in the clival region. T2WI showed that the lesion was mainly slightly hyperintense with only narrow areas of hyperintensity. Given the pathological results, the low signal intensity on T2WI was likely due to the dense arrangement of tumor cells and scarcity of mucous cells. On the contrast-enhanced scan, the focus was not uniformly enhanced, the small cystic area was not enhanced, and the typical honeycomb sign was not observed.

Chordoma in the petrous mastoid region should be differentiated from the following tumors

| Imaging | Chordoma | Jugular glomus tumors | Middle ear cancer | Chondrosarcoma | Solitary fibroma tumor |

| CT | Irregular low-density mass with calcification and well-defined boundaries, expansive growth, and the surrounding bone is absorbed and destroyed | Low-density mass, osteolytic destruction with flaky calcification | Soft-tissue density mass with ill-defined, surrounding bone absorption and destruction | Both feature calcification and surrounding bone infiltration in the mass | Soft-tissue density mass with well-defined boundaries, the most of adjacent bones show compressive changes |

| MRI | Obvious hyperintensity and a “beehive-like” appearance on T2WI, and honeycomb sign of obvious enhancement | A “salt and pepper sign” on T2WI, and significant enhancement | Soft tissue mass with the middle ear as the center, an unclear boundary, and enhanced inhomogeneous enhancement | Significantly high signal on T2WI, and inhomogeneous enhancement | Attached to the dura mater with, obvious enhancement, and hypointense area (collagen fibers) on T2WI |

Chordoma occurring in the petrous mastoid region is rare, its imaging findings are rarely reported, and an understanding of its MRI findings is lacking. However, in the differential diagnosis of petrous mastoid tumors, chordoma should be considered, especially when lobulated masses are found. The T2WI results are mainly characterized by a high signal intensity, obvious enhancement, and surrounding bone absorption and destruction. Therefore, an imaging examination can sufficiently show the extent of the focus and surrounding involvement, which can provide more useful information for clinical treatment.

We acknowledge Wang YJ and Huang C, Department of Radiology of Zhejiang provincial hospital of Chenese Medicine and No. 926 Hospital, Joint Logistics Support Force of PLA, for his special contribution to this case. We acknowledge the work of colleagues in the Pathology and Radiology Department in offering the original images and data related to this article.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Neuroimaging

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Verde F, Italy S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Stiller CA, Trama A, Serraino D, Rossi S, Navarro C, Chirlaque MD, Casali PG; RARECARE Working Group. Descriptive epidemiology of sarcomas in Europe: report from the RARECARE project. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:684-695. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Chen QQ, Liu Y, Chang CD, Xu YP. Chordoma located in the jugular foramen: Case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e15713. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Tirabosco R, Mangham DC, Rosenberg AE, Vujovic S, Bousdras K, Pizzolitto S, De Maglio G, den Bakker MA, Di Francesco L, Kalil RK, Athanasou NA, O'Donnell P, McCarthy EF, Flanagan AM. Brachyury expression in extra-axial skeletal and soft tissue chordomas: a marker that distinguishes chordoma from mixed tumor/myoepithelioma/parachordoma in soft tissue. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:572-580. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Dwivedi RC, Ojha BK, Mishra A, Youssefi P, Thway K, Hassan MS, Agrawal N, Kazi R. A rare case of jugular foramen chordoma with an unusual extension. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137:513-516. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Ropper AE, Cahill KS, Hanna JW, McCarthy EF, Gokaslan ZL, Chi JH. Primary vertebral tumors: a review of epidemiologic, histological and imaging findings, part II: locally aggressive and malignant tumors. Neurosurgery. 2012;70:211-9; discussion 219. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Stacchiotti S, Sommer J; Chordoma Global Consensus Group. Building a global consensus approach to chordoma: a position paper from the medical and patient community. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e71-e83. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Erdem E, Angtuaco EC, Van Hemert R, Park JS, Al-Mefty O. Comprehensive review of intracranial chordoma. Radiographics. 2003;23:995-1009. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Meyers SP, Hirsch WL, Jr, Curtin HD, Barnes L, Sekhar LN, Sen C. Chordomas of the skull base: MR features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1992;13:1627-36. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Anis N, Chawki N, Antoine K. Use of radio-frequency ablation for the palliative treatment of sacral chordoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1589-1591. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |