Published online May 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i13.4131

Peer-review started: April 18, 2021

First decision: September 28, 2021

Revised: October 9, 2021

Accepted: April 8, 2022

Article in press: April 8, 2022

Published online: May 6, 2022

Diffuse lamellar keratitis (DLK) is a complication of laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK). This condition can also develop after small-incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) with a distinctive appearance. We report the case involving a female patient with delayed onset DLK accompanied by immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy.

A 22-year-old woman was referred to our department for DLK and a decline in vision 1 mo after undergoing SMILE. The initial examination showed grade 2 DLK in the flap involving the central visual axis of the right eye. She was immediately administered with a large dose of a topical steroid for 30 d. However, the treatment was ineffective. Her vision deteriorated from 10/20 to 6/20, and DLK gradually worsened from grade 2 to 4. Eventually, interface washout was performed, after which her vision improved. DLK completely disappeared 2 mo after washout. Six months after SMILE, the patient was diagnosed with IgA nephropathy due to a 4-year history of interstitial hematuria.

DLK is a typical complication of LASIK but can also develop after SMILE. Topical steroid therapy was ineffective in our patient, and interface washout was required. IgA nephropathy could be one of the factors contributing to the development of delayed DLK after SMILE.

Core Tip: Diffuse lamellar keratitis (DLK) is a typical complication of laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis but could also develop after small-incision lenticule extraction (SMILE). Topical steroid therapy was ineffective in our patient, and interface washout was required. Immunoglobulin A nephropathy could be one of the factors contributing to the development of delayed DLK after SMILE.

- Citation: Dan TT, Liu TX, Liao YL, Li ZZ. Delayed diffuse lamellar keratitis after small-incision lenticule extraction related to immunoglobulin A nephropathy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(13): 4131-4136

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i13/4131.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i13.4131

A 22-year-old woman was referred to our department for diffuse lamellar keratitis (DLK) and a decline in vision 1 mo after undergoing small-incision lenticule extraction (SMILE). The initial examination showed grade 2 DLK in the flap involving the central visual axis of the right eye (OD). She was immediately administered with a large dose of a topical steroid for 30 d. However, the treatment was ineffective. Her vision deteriorated from 10/20 to 6/20, and DLK gradually worsened from grade 2 to 4. Eventually, interface washout was performed, after which her vision improved. DLK completely disappeared 2 mo after washout. Six months after SMILE, the patient was diagnosed with immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy due to a 4-year history of interstitial hematuria.

A 22-year-old female patient presented with a 1-wk history of gradual vision loss.

The patient had undergone bilateral SMILE 1 mo before and showed no other medical history.

The patient’s medications did not contribute to her vision loss.

The patient’s personal and family history did not contribute to her vision loss.

The preoperative best-corrected distance visual acuity (DVA) was 20/20 in both eyes (OU) with refraction of -7.25 diopter sphere (DS) -0.5 diopter cylinder (DC)*20 OD and -6.50 DS -0.50 DC*148 in the left eye (OS). The results of slit-lamp and dilated fundus examinations were normal, with no sign of dryness or superficial punctate keratopathy. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was 11.3 mmHg OD and 17 mmHg OS. Central corneal thickness was 650 μm OD and 642 μm OS. Specular microscopy revealed an endothelial cell density of 2756 cells/mm2 OD and 2929 cells/mm2 OS with a uniform endothelial cell pattern without any sign of abnormalities.

The laboratory findings, including those of routine blood examination and tests for HBV, HCV, HIV, and RPR, were unremarkable.

DLK after SMILE.

The patient’s postoperative regimen consisted of topical levofloxacin 0.3% and artificial tears 4 times a day hourly OU, and topical fluorometholone 0.1% OU 4 times daily for the first week with the daily dose reduced by one drop every week. At her 1-wk postoperative visit, the uncorrected DVA (UDVA) was 16/20 OD and 16/20 OS. The manifest refraction at 1 wk was +0.5 DS OD and +0.25 OS. At this point, the IOP was 11.3 mmHg OD and 17 mmHg OS. She was told to continue tapering his medication regimen and return for her 1-mo follow-up visit.

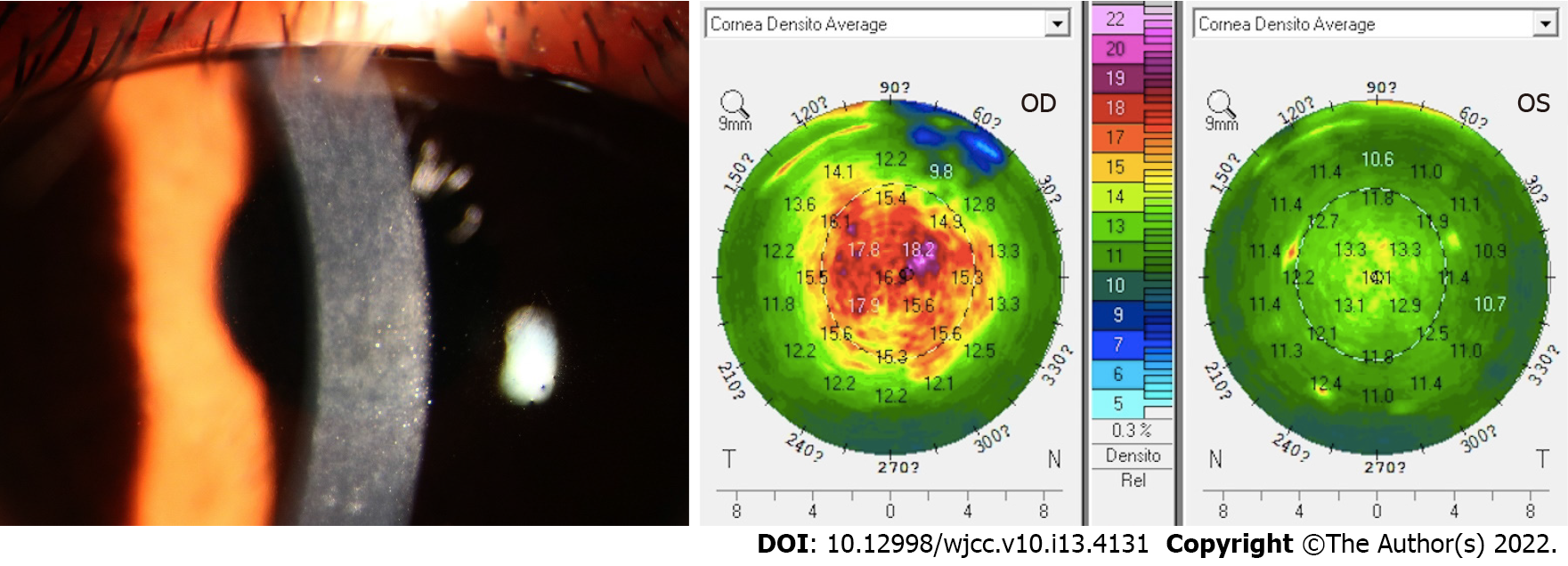

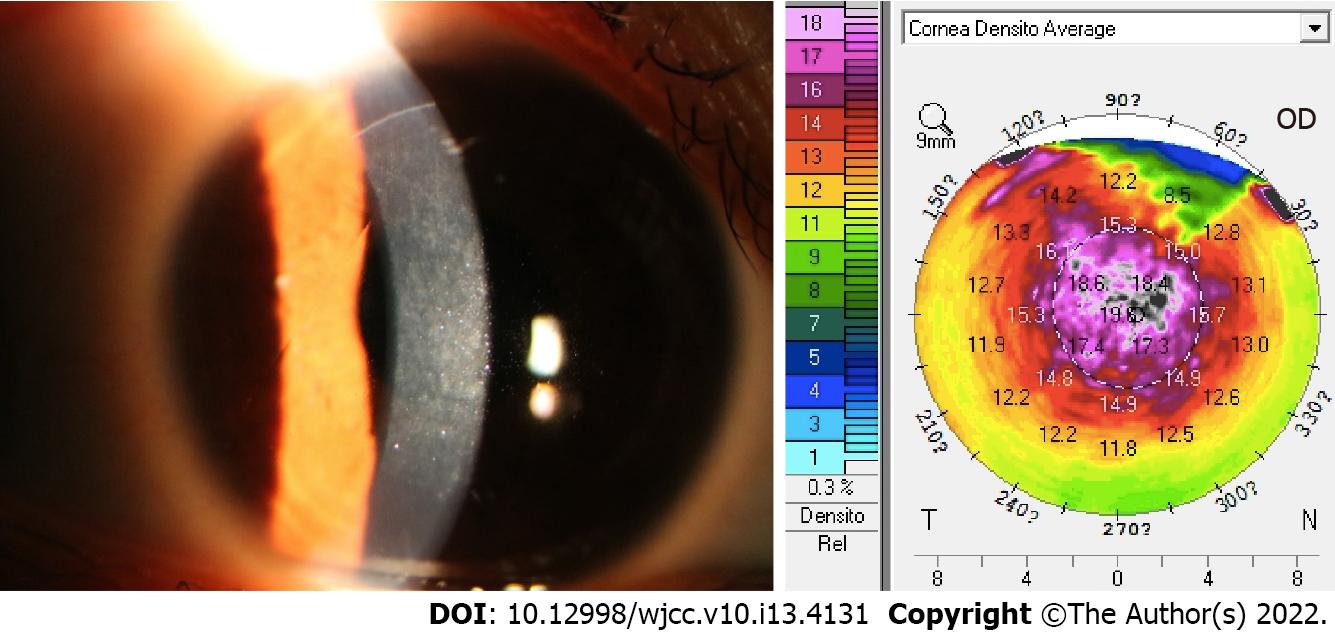

However, 1 mo later, the patient presented with sudden worsening of symptoms; her vision was hazy and she did not experience pain or any other sensation, which she started experiencing 1 wk before the visit. The UDVA was 10/20 OD and 16/20 OS, and the manifest refraction was -1.25 DS = 16/20 OD. OD showed large focal infiltrates in the flap involving the central 6-mm visual axis (grade 2 DLK). OS was slightly infiltrated (grade 1 DLK). The IOP was 7.5 mmHg OD and 8.0 mmHg OS. A Pentacam assessment showed that the average optical density was 18.4 (Figure 1) OD and 13.8 OS. On the basis of these findings, she was diagnosed as showing DLK with myopia OD. She was advised to be treated with fluorometholone 0.1% OD 6 times daily 1 wk later. Her symptoms did not improve; therefore, she was prescribed 1% prednisolone acetate eye drops OD 8 times daily instead of TobraDex, the frequency of which was gradually reduced to 6 times daily for 1 wk. Two weeks later, i.e., 2 mo after the operation, she presented with worsening of symptoms and cloudy vision OD. The UDVA declined to 6/20 OD. The manifest refraction was -1.50 DS = 14/20 OD with more large focal infiltrates in the flap involving the central 6-mm visual axis compared to before (grade 4 DLK). The IOP was 8.5 mmHg, and a Pentacam assessment showed that the average optical density was 19.5 D (Figure 2). Interface washout was eventually performed with a balanced salt solution and 0.1 mg dexamethasone. Her treatment regimen then consisted of topical fluorometholone 0.1% OD 4 times daily for the first week with the daily dose reduced by one drop every week. Thirteen days later, the UDVA was 10/20 -0.75 DS -0.75 DC*38 = 16/20 OD, and there were few focal infiltrates in the flap involving the central 6-mm visual axis (grade 2 DLK). The IOP was 9 mmHg. The densitometry value was 18.4 D. A bacterial smear test showed no positive findings.

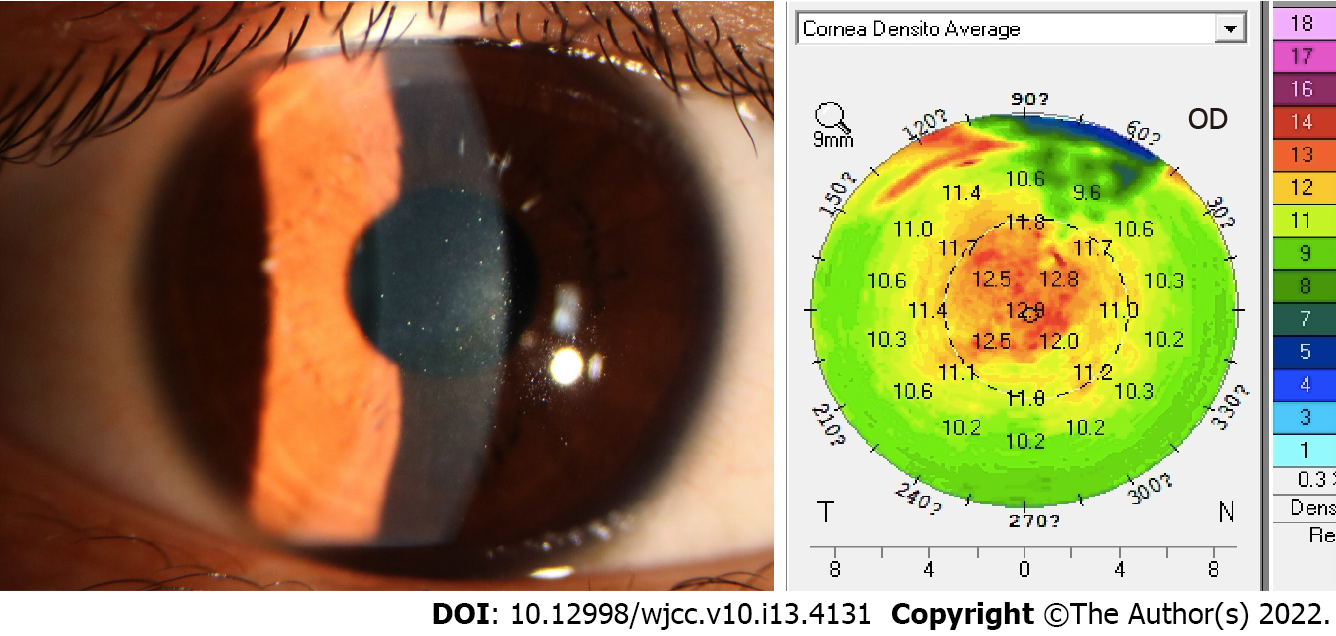

Two months later, the patient reported a subjective improvement in VA; the UDVA was 16/20, and the DLK severity was grade 1. The average optical density was 19.6 D, and the IOP was 8.7 mmHg. Five months later, the UDVA was 16/20 and the DLK had completely disappeared (Figure 3). The densitometry value (12.6 D) was similar to that before the operation, 12 D. The patient was diagnosed as showing IgA nephropathy due to "interstitial hematuria for 4 years" at 6 mo after SMILE. Biochemical examination showed a serum albumin level of 30.0 g/L (reference value: 35-55 g/L). Routine urine examination showed the following findings: Urine albumin (+++) and occult blood (+++). Protein electrophoresis yielded the following findings: Albumin, 55.1% (reference value: 53.8%-66.1%); α1 globulin, 5% (reference value: 1.1%-3.7%); α2 globulin, 14.3% (reference value: 3.2%-6.5%). Renal biopsy showed aortic arteriosclerosis; IgM (++); IgA (++); C3d (+++); and C4d (+).The patient was eventually diagnosed as having postoperative SMILE OU, delayed DLK with myopia OD, and IgA nephropathy.

DLK rarely occurs in SMILE surgery. The incidences of DLK after microkeratome laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK), femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK, and SMILE range from 0.1% to 12.1%[1,2], 0.4% to 37.5%[3,4], and 0.2%-0.45%[5,6], respectively. The 2-4 mm corneal stroma incision in SMILE may reduce the risk of introduction of various foreign bodies into the corneal interface in comparison with that associated with the 20-mm corneal stroma incision in LASIK. However, SMILE may also have specific features that may lead to DLK: (1) The femtosecond laser bubbles increase antigen composition and space to stimulate inflammation[1]; (2) The excessive manipulation in thinner lenticules and the larger diameter may stimulate the secretion of inflammatory factors and increase the incidence of DLK[7]; (3) The higher laser energy may cause severe corneal stroma damage[8]; (4) The repeated use of negative pressure suction during surgery may cause epithelial damage leading to DLK; (5) Other agents such as meibomian gland secretions[9,10], oil, irrigating fluid, talc powder, traumatic flap dislocation, air dust, bacteria, and other stimulating inflammatory factors may be associated with DLK[11,12]; and (6) There are individual patient differences in sensitivity to lasers.

DLK usually occurs within 24 h and rarely appears 5 d after SMILE[6]. In this case, the surgical procedure was performed smoothly, and the patient’s vision improved at 1 mo after the procedure, consistent with the findings reported by Lin et al[13]. DLK is highly sensitive to steroid therapy, and the majority of cases can be managed with aggressive topical steroid treatment[14,15]. Therefore, steroid therapy and topical steroid treatment are routinely administered. Previous data showed that interface washout may increase the risk of corneal melting associated with focal infiltrates[16]. Therefore, in our case, interface washout was eventually performed after 2 mo, not 1 mo, of hormone therapy. Thus, once topical steroid therapy showed no efficacy, interface washout should be performed.

In this case, DLK was delayed and lasted for more than 4 mo. In addition to treatment-related factors, the patient’s systemic factors may have been responsible for the atypical presentation. The patient had been diagnosed with IgA nephropathy due to "interstitial hematuria for 4 years" at 6 mo after SMILE. IgA nephropathy is a form of glomerulonephritis characterized by deposition of the IgA antibody in the glomerular mesangial area, and the typical clinical presentation is gross hematuria. The specific etiology and mechanism of this condition are complex and include immune complex deposition, mucosal immunodeficiency, IgA molecular abnormalities, and microbial factors. Ocular involvement in patients with IgA nephropathy is rare; however, the most frequent association occurs with scleritis, episcleritis keratoconjunctivitis, uveitis, and retinal vasculopathy[17]. To our knowledge, there is no study that directly shows delayed DLK after SMILE and IgA nephropathy. Tears contain a large number of SIgA and small amounts of IgA, and tear SIgA and serum IgA have the common antigenicity. IgA in tears is 3-8 times than that in the blood. IgA abnormalities in plasma affected by abnormal blood may result in sIgA and IgM abnormalities in tears to ocular corneal and conjunctival inflammation[18]. Unfortunately, we did not detect the IgA in tears and interface washing fluid. Li et al[19] reported a DLK occurring 4 years after SMILE because of trauma and it had cured with intensive topical corticosteroid eyedrops. As we know, IgA nephropathy needs a sufficient dose of glucocorticoid therapy, but in our case, glucocorticoid was too little to get curative effect and ocular surface drugs cannot reach the flap interface in early time. Until 2 years later, this patient still received a maintenance dose of glucocorticoid.

In addition to these factors, plasma albumin, complement, and inflammatory factors may be related to the presentation of DLK. Corneal nutrition is derived from aqueous humor, tears, and the limbal sclera, and laser postoperative healing may result in inflammatory cell-mediated interference via multiple antibiotic factors. Changes in the albumin, complement, and inflammatory factor content in the plasma can cause changes in the lymphocytes, plasma cells, complement, and inflammatory overexpression in the corneal epithelium, tears, and scleral edge as well, directly or indirectly triggering an indirect immune response to the corneal gland and resulting in DLK. It has been proven that the aggregation of inflammatory cells along with interface debris presence were detected by corneal confocal microscopy in DLK patient’s cornea after SMILE[20].

Autoimmune diseases are relative contraindications to SMILE. The hidden onset, the patient's lack of consciousness, and the absence of preoperative urine and kidney function examinations as routine tests led to a missed diagnosis. The patient had a 4-year history of hematuria, so her kidney disease was not controlled when she underwent surgery. Despite the long treatment process, she had good treatment and achieved satisfactory results in this special case. This case indicates that IgA nephropathy in patients may be one of the factors related to delayed DLK in patient after SMILE. Moreover, the preoperative history cannot be ignored, especially a history of autoimmune diseases.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Patel VJ, India S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Gao CC

| 1. | Gil-Cazorla R, Teus MA, de Benito-Llopis L, Fuentes I. Incidence of diffuse lamellar keratitis after laser in situ keratomileusis associated with the IntraLase 15 kHz femtosecond laser and Moria M2 microkeratome. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:28-31. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lira LH, Hirai FE, Oliveira M, Portellinha W, Nakano EM. Use of the Ishikawa diagram in a case-control analysis to assess the causes of a diffuse lamellar keratitis outbreak. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2017;80:281-284. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Haft P, Yoo SH, Kymionis GD, Ide T, O'Brien TP, Culbertson WW. Complications of LASIK flaps made by the IntraLase 15- and 30-kHz femtosecond lasers. J Refract Surg. 2009;25:979-984. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tomita M, Sotoyama Y, Yukawa S, Nakamura T. Comparison of DLK incidence after laser in situ keratomileusis associated with two femtosecond lasers: Femto LDV and IntraLase FS60. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1365-1371. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Xin X, Li SY, Zhao AH, Liu XY, Pei J, Liu XF. Observation on complications after femtosecond laser small incision lenticule extraction in 1000 eyes. Zhonghua Yan Waishang Zhiye Yanbing Zazhi. 2017;39:619. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Reinstein DZ, Stuart AJ, Vida RS, Archer TJ, Carp GI. Incidence and Outcomes of Sterile Multifocal Inflammatory Keratitis and Diffuse Lamellar Keratitis After SMILE. J Refract Surg. 2018;34:751-759. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhao J, He L, Yao P, Shen Y, Zhou Z, Miao H, Wang X, Zhou X. Diffuse lamellar keratitis after small-incision lenticule extraction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41:400-407. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kouassi FX, Blaizeau M, Buestel C, Schweitzer C, Gallois A, Colin J, Touboul D. [Comparison of Lasik with femtosecond laser vs Lasik with mechanical microkeratome: predictability of flap depth, corneal biomechanical effects and optical aberrations]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2012;35:2-8. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu YY, He W, Xu L, Zheng CH. Assessment of the correlation between Meibomian gland dysfunction and the incidence of DLK after femtosecond laser LASIK. Guoji Yanke Zazhi. 2017;17:180-183. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Brito BE, Zamora DO, Bonnah RA, Pan Y, Planck SR, Rosenbaum JT. Toll-like receptor 4 and CD14 expression in human ciliary body and TLR-4 in human iris endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:203-208. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Holland SP, Mathias RG, Morck DW, Chiu J, Slade SG. Diffuse lamellar keratitis related to endotoxins released from sterilizer reservoir biofilms. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1227-33; discussion 1233. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 98] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cabral-Macias J, García-De la Rosa G, Rodríguez-Matilde DF, Vela-Barrera ID, Ledesma-Gil J, Ramirez-Miranda A, Graue-Hernandez EO, Navas A. Pressure-induced stromal keratopathy after laser in situ keratomileusis: Acute and late-onset presentations. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44:1284-1290. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lin KJ, Chen J, Lin W. SMILE postoperative delayed diffuse lamellar keratitis with interlaminar vacuoles: a case. Chin J Optom Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;19:315. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Hoffman RS, Fine IH, Packer M. Incidence and outcomes of lasik with diffuse lamellar keratitis treated with topical and oral corticosteroids. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29:451-456. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | MacRae SM, Rich LF, Macaluso DC. Treatment of interface keratitis with oral corticosteroids. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28:454-461. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Stuart A, Reinstein DZ, Vida RS, Archer TJ, Carp G. Atypical presentation of diffuse lamellar keratitis after small-incision lenticule extraction: Sterile multifocal inflammatory keratitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44:774-779. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | El Matri K, Amoroso F, Zambrowski O, Miere A, Souied EH. Multimodal imaging of bilateral ischemic retinal vasculopathy associated with Berger's IgA nephropathy: case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21:204. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Allansmith MR, Radl J, Haaijman JJ, Mestecky J. Molecular forms of tear IgA and distribution of IgA subclasses in human lacrimal glands. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1985;76:569-576. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li M, Yang D, Chen Y, Li M, Han T, Zhou X, Ni K. Late-onset diffuse lamellar keratitis 4 years after femtosecond laser-assisted small incision lenticule extraction: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17:244. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rana M, Adhana P, Ilango B. Diffuse Lamellar Keratitis: Confocal Microscopy Features of Delayed-Onset Disease. Eye Contact Lens. 2015;41:e20-e23. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |