INTRODUCTION

Commentary on the psychosocial macro world

At present, we seem to live in a persistent post-normal state of society, especially as many crises such as migration, pandemics, wars, and the climate crisis overlap. We are confronted with multiple, interdependent crises[1]. This situation challenges the competence of the sciences to understand the situation and develop coping strategies for the knowledge society, which must be communicated in an understandable way, taking into account both the internal consistencies of their narratives and structural characteristics of the affective-cognitive level of citizens.

As an example of a challenge for public health, we refer here to the corona pandemic, in particular by highlighting the problem of consistency of health information and the mechanisms for building resilient mindsets that also reflect the influence of the sociocultural environment. We gradually develop a comprehensive multilevel model in which we first start from observable cognitive dissonances, and then conceptually combine this level with the psychoanalytic view of the dynamics of affects and motivations that must be regulated by ego functions. Finally, by use of a systems theoretical model of the mind we link this psychological model to a broader social-ecological conceptual framework. We hypothesize that the aversive reactions of an increasing part of the population to public health measures are based on the individual experience of a “bad” relationship with an increasingly fragmented world, which in addition may also lead to an increasingly fragmented self in the respective psychosocial development of the people. We therefore believe that pandemic management and public health interventions in general could be more efficient if they take into account these psychosocial aspects of people as “situated subjects” and make greater use of transparent theory-based narratives.

Productive and counterproductive power of simple but contradictory narratives: In modern societies, communication is largely based on scientific information, even if it is transformed into other, simpler descriptive and also regulatory narratives. Here we understand a narrative as a text that encodes values and emotions in order to create meaning and to give people affective and cognitive orientations, and that legitimizes a certain collective behavior[2]. Narratives are also an important basis of “knowledge societies.”

With regard to the corona pandemic, various narratives contributed to the “infodemic”, as the World Health Organization called the huge corona-related psychosocial information environment[3]. Above all, the effects of the different health regulations such as general lockdowns and their on’s and off's were internationally varying and not really comprehensible, i.e. scientifically satisfactory proven (e.g., wearing masks while skiing, but not in shops). Such inconsistencies caused by politics and/or science arise above all from the temporary construction of messages consisting of one-sentence or even one-word narratives, which are also increasingly communicated incoherently, as is typical in postmodern societies[4]. Such narratives about the corona pandemic were modified within a few months: “There will be millions of deaths” was communicated in European countries in spring 2020 and new narratives emerged in spring/summer 2021, such as: “The pandemic is over”. It called for “protecting vulnerable individuals”, “protecting health care”, and finally “getting vaccinated”, as “the pandemic is a pandemic of the unvaccinated” (Fall 2021). When the rapidly spreading but not so pathogenic omicron variant appeared in December 2021, mandatory vaccinations were propagated. However, this public health program could not function effectively because this type of virus was spreading at a very rapid pace, and time was short to carry out the vaccinations. As a result, the motivation to vaccinate did not increase[5]. The radicalization of the skeptical part of the population also increased.

As a consequence, there was a change in the conditions of public opinion formation regarding corona: a new simple rationality emerged, which seemed to be scientifically evidence-based, but which was propagated with insufficient justifications, differentiations, and updates. After a while, resentment was articulated in the population and through subtle systemic ping-pong processes, social radicalization gradually took place. Put simply: The collective imperatives were accepted or rejected - “Let's follow the science” or “The Great Reset[6] is behind it”!

This phenomenon of polarization is often interpreted as a “reactance reaction”, since slightly skeptical attitudes of citizens can change into a passive (or even active) opposition in interaction with the given view of politics, the media and the sciences. A first stage of a theoretical explanation for such attitude dynamics at the individual level could be the theory of cognitive dissonance as it will be explained later. First, however, basic social mechanisms of the splitting of individual and collective consciousness will be explained.

“Spiral of silence” and the need for social acceptance: First, we hypothesize that information inconsistencies in public health communications have been instrumental in the emergence of an increasingly aggressive polarization of the social atmosphere during the pandemic. For example, at the beginning of 2022, more and more people seemed to belong to the silent majority, who may have arisen via the mass media strategy of the “cancel culture”[7] and the sociopsychic mechanisms such as the “spiral of silence”[8]: The more dissenting opinions (and even questions) from the institutions occured, the more these people were silenced and spontaneously fell silent. And the more they remained silent, the more the opinion of the institutions prevailed, thus reinforcing the conformity of public opinion. With regard to this process, it must generally be assumed that, among other things, the contact-preventing lockdowns led to the fact that people's essential need for social acceptance could no longer be satisfied, although this need could be partially satisfied by the use of social media.

Due to the psychohygienic relevance of good human social relationships, we shall first examine the reciprocal relationship between the person and her social environment in the context of psychological findings of individual development (terms we use here are elaborated in Supplementary material).

Basic interactions between the psychosocial environment and individual development: In view of the reduced social dialogue associated with the implementation of mandatory restrictive measures to combat the pandemic, a polarization of the social climate became apparent: The good guys as followers and the bad guys as resisters. This increasingly developing division of society overshadowed the current cultural change of modern societies, which is characterized by an accelerated increase in differentiated but also disintegrated narratives at macro, meso, and micro levels (“disintegrated pluralism”). This fragmented character of the sociocultural environment[9] in turn favors the individual development of “dissociated personalities”, and thus in this “fragmented acceleration society”[10] a fundamental “loss of (coherent) resonance” of the individuals[11] arises. In relation to borderline personality disorder, narcissism and identity, and authenticity[12-14], psychoanalysis, in particular, has provided a great deal of empirical and theoretical knowledge about such features of the psychosocial development of the individual (e.g., in the context of the influential object relations theory based on developmental phases)[15]. We want to shed light on these aspects here by starting with the theory of cognitive dissonance, which we then combine with psychoanalysis, and finally outlining a human-ecological point of view.

Theoretical framework models for a psychological understanding of the individual coping with the infodemic

In terms of the interrelationship between the structure of the social world and the evolving personality structure, we see a correspondence between the inconsistencies of the infodemic and the fragility of basic affective-cognitive[16,17] schemata of the individual: if the individual’s current experiences exhibit a high degree of inconsistency, the resulting affective-cognitive structures are restructured towards a more stable constellation[18] (theory of cognitive dissonance)[19]. Moreover, such adaptations can be understood by defense mechanisms as identified by psychoanalysis (e.g., rationalizing, suppressing). Finally, we use the structural model[20] and self-theory[21] of psychoanalysis by referring to systemic models of the mental (essential theoretical terms we use here are explained in Supplementary material).

Cognitive dissonance: We begin with the information environment of the individual, i.e. the social cognitive sphere. In this context, the psychopathological relevance of the need for orientation as identified by Grawe[22] can be assumed in principle: if a set of cognitions does not match their affective charges, a cognitive dissonance occurs with a negative basic emotionality, which enhances the need for orientation. We also assume that this intrinsic affective-cognitive imbalance occurs when the individual is in a state of information overload during affective-cognitive information uptake. The overload results from and during the construction of a cognitive schema that interacts with the basic internal affective-cognitive schema previously established by the individual development. If the need for orientation is not satisfied by the environment, the affective-cognitive balance of the person is restored by mainly unconscious mechanisms.

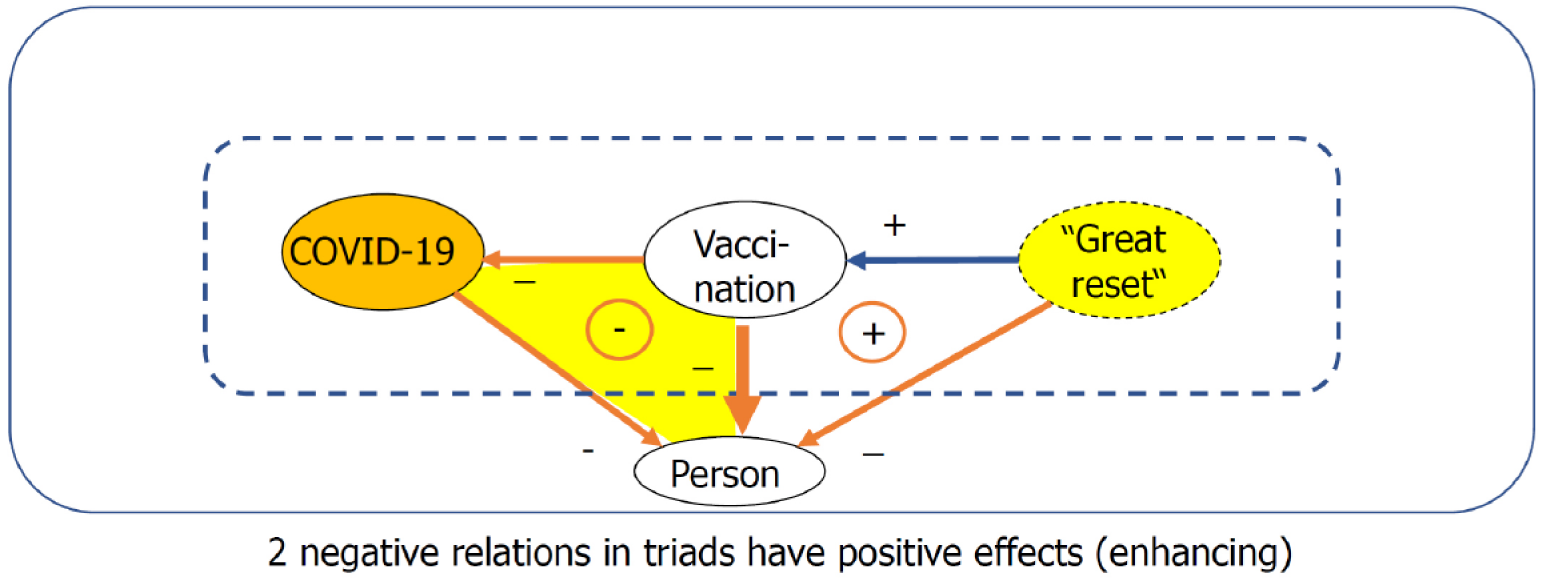

At first glance, the acute harmonization dynamics can now be successfully described by the theory of “cognitive dissonance”[19,23,24], which explains the quasi-automatic balancing[25,26] of inconsistent cognitive structures[27] (Supplementary material). Consequently, the concept of cognitive dissonance can be applied to cognitions during the pandemic. The cognitions were singular but emotionally charged narratives that practically fit together, such as skepticism about vaccinations and the options of conspiracy theories (Figure 1). A system of relations in the form of a “negative triad,” consisting of the person experiencing both coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and vaccination negatively, leads to a dissonant unstable constellation (left triangle; three negative relations). An additional affective-cognitive element such as “The great reset,” which is not liked but is believed to propagate also vaccination, stabilizes the entire system (right-angled triangle; two negative relations in triads have positive enhancing effects). Although this example has some shortcomings in terms of oversimplification, it is helpful for understanding resistance to change of opinions and attitudes.

Figure 1 A hypothetical cognitive scheme of people with vaccine resistance stabilizing through conspiracy narratives (“The Great Reset”).

See the text for more information. COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019.

Now the question arises why and how the respective stabilizing element emerges and where it comes from. Here we hypothesize that a fragmented and disintegrated internal model of the world and the self acts as an affective-cognitive reference structure stored in (implicit) long-term memory for the current information processing and causes the stabilization or destabilization of topic-specific and current affective-cognitive information, which is likely to form mainly in working memory and short-term memory. Thus, a stable “self” is likely to have a higher tolerance for inconsistent external information.

It should be noted here too that the well-known resistance to changes of such mindsets is a central issue in health issues in context of public health. This is a challenge in addiction psychology and implies motivational interventions by therapists[28,29]. In line with this microtheory, it must be acknowledged that a broader conceptual framework of theoretical psychology is useful, as health psychologist Robert West has shown with regard to smoking[30]. In addition to the cognitive level, West also emphasizes the importance of the affective-motivational level of the mental, and he points to the need for a differentiated integrative model of general psychology (PRIME model), a topic recently highlighted by the authors[17]. Here, we first follow the traditional theory-integrating path of psychoanalysis, namely the developmental psychological perspective of object relations theory[31].

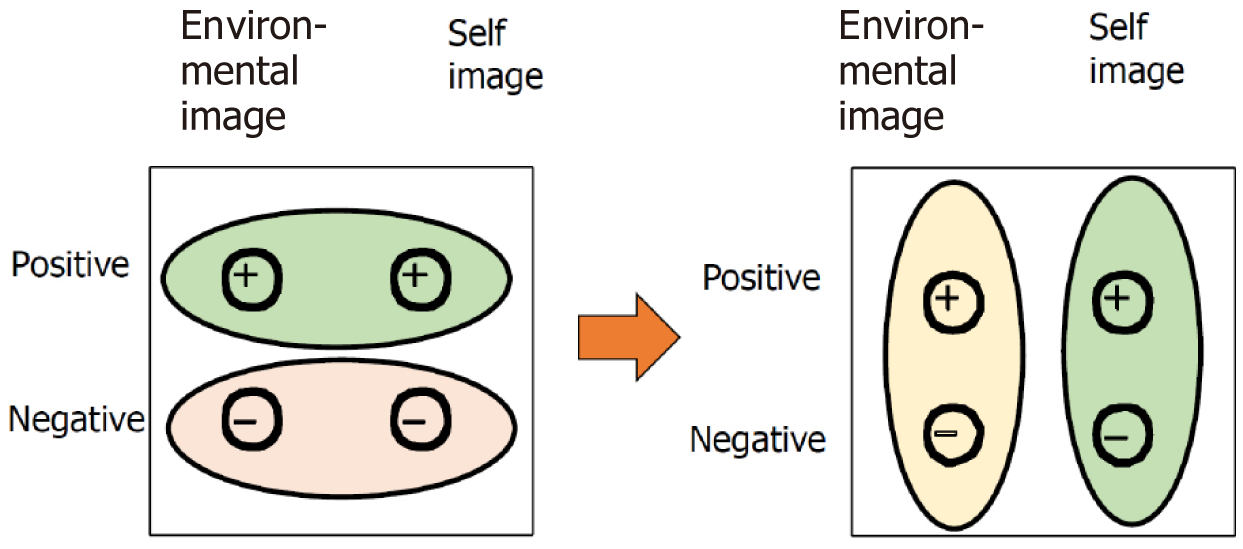

Developmental fragility of the affective-cognitive reference structure: According to the object relations theory (Supplementary material), at the beginning of psychological development there is initially no internal reference structure for the affective-cognitive order that fits the environment: Elements of conscious experience are classified separately and only polarized as “good” and “bad” experiences (Figure 2). In addition, at this stage of development, there is a lack of stable affective-cognitive object relations that distinguish the self and the environment[32] sufficiently. This structure therefore resembles a psychotic personality structure[31].

Figure 2 The core concept of object relations theory visualized as a quadripolar “experience matrix”: The low-developed polarized configuration of the representations of the self and the environment with poles of positive and negative experiences (left) and the adult configuration with strong distinction of the images of the environment and the self (right)[31].

For simplification, the term “object representation” is translated here as “environmental image”; “Self-representation” is also translated as “self-image.”

For some individuals, the lifelong interaction between two basic dimensions of human experience of relations - connectedness with others vs self-determination - is deficient and leads to a high vulnerability of human-environment relationships[33,34]. In this understanding, with a view to the evolving process of interaction with meaningful others[31], the cumulative and socially engrammed self-representations can be understood as a “constant frame of reference” embedded in the self. It serves as a benchmark with future social cognitions associated with affects[21,35]. Social engrams[36] and empathic behavior[37] have been shown to influence higher-order cognition and modulate negative experiences and memories, in part by facilitating learning new ones[38].

Following the object relations theory[31], it is now assumed that the basic reference structure for the current affective-cognitive information processing is provided by the internal representation of object relations[31] or the "internal working model", which refers to the meaning of the self-foreign distinction[39]. For the sake of simplicity, we call this affective-cognitive structure “experience matrix”[32] (Figure 2). Its essential structural properties converge into a growing dynamic balance of emotionally valued diversity and integrity of relationships between the elements. In our systemic transformation of object relations theory[17], the value of the respective cognitions (plus, minus) indicates the emotional evaluations that are the result of interactions of cognitions. If there is an inconsistent relationship, orientation needs and control needs arise and stabilization processes to reduce cognitive dissonance take place[25,30].

It can now be hypothesized that obstacles to adequate affective-cognitive development arise from the fear of losing the self, coherence, orientation in life, and even existence, when circumstances challenge people's current configuration of the self. In light of the megatrends in modern societies mentioned at the beginning, and in light of the narratives of the pandemic, it seems important to note that the modulating function of language in accordance with affect regulations (and the self-regulation) depends on the quality of the social relationship as learned in past and current interactions[40,41]. Empirical evidence for the latter has been proven over decades in psychotherapeutic process and outcome research[42].

Applied to the experience of the 3 years of the pandemic, it should be emphasized, for example, that with the fluctuating need to reduce social contacts, the need for social belonging was antagonized, resulting in a persistent mixture of fear of contagion and an aggressive-depressive mood state to limit social contacts. In our model, these emotional conflicts are also interrelated, similar to how they are conceptualized in the phenomenology of emotions and in neurobiology[43,44].

Interplay of suppressed needs and emotions: The model of the affective-cognitive subsystem of the mental must be supplemented with regard to the persistent situation of need suppression in order to explain a comprehensive but diffuse aggregation of negative emotions[17]. Here are some simple examples that can be localized on the need-emotion axis: Physical displeasure follows the suppression of the need for space and movement: (1) Anxiety is a reaction to the suppressed need for physical safety and protection (e.g., before the virus), followed by the aforementioned lack of orientation and control, as a correlate of two needs that are of psychopathological relevance[17,22,27]; (2) Aggression can occur in response to the suppression of the need for self-determination; and (3) Depression follows the ongoing suppression of positive social relationships.

These systemic affective-motivational relations can be partially compensated as a coping strategy by a cognitive restructuring of the respective experiences. In view of the corona pandemic, therefore, a future option for collective psychological stabilization could be a simplified and scientifically sound but generally consistent descriptive and explanatory "theoretical model of the pandemic" (e.g., infection epidemiological triade model) that allows for higher cognitive consistency. This model should integrate the diverse and sometimes contradictory information of the pandemic in a simple way, facilitating a mental order in relation to the external situation.

Basic need for space and its regulations - a new experience: In the context of emotional responses to the ongoing suppression of needs, in view of the long-lasting behavioral restrictions during the pandemic, it is worth mentioning the suppression of the need for space and freedom of movement, an aspect elaborated by ecological psychology (Supplementary material). The need for space is - albeit culturally different-a fundamental need of the “situated subject”, but underscored by research. In particular, ecological psychology and behavioral biology have emphasized that it is not so much a high or low social density that is affectively important, but above all the autonomy of the regulation of physical distance and proximity is relevant[45-48]: In its importance for territoriality, it is a source of serious conflicts, and therefore it is a basic need[46-50] for living beings to be able to self-regulate distance. It should also be mentioned here that this need for self-determination in the field of mobility is an independent need, although it is only a form of the basic need for self-determination in all areas of life. As a basic biological need, its suppression can contribute to the psychodynamics of pathogenic symptom and syndrome formation[51].

The psychological significance of the need for space was highlighted in the context of the pandemic through public health measures such as distancing and isolation and through lockdowns. These restrictions on “mobility,” imposed in most countries of the world and applied for several weeks to suppress the dynamics of transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, led to the suppression of freedom of movement and produced a complex of negative emotions, mainly aggression and depression, as mentioned above. This basic form of restriction of personal freedom persisted, and the suffering under these circumstances also varies from culture to culture and also within cultures, for example in relation to social class. However, everyday experience already shows that a high density of space (e.g., in the family's apartment during lockdown) can cause stress, but can also lead to the experience of security. The observation of the external emptiness can also lead to an individual and situational condition (e.g., in the apartment as a single) to the experience of freedom and relaxation, but this situation can also soon cause discomfort and anxiety (horror vacui). All of these conflicting experiences were reported by patients during the corona crisis.

After discussing different levels of mental processing (cognition, affects, needs), this psychological perspective needs to be expanded to increase the ecological validity of the model and to better understand the dynamics of internal and external inconsistencies. We therefore “zoom” out of the focus model and look at the entire system of the mental and its connections to the environment.

Mental and action as a control loop - the structural model of psychoanalysis combined with action theory: A more holistic view of the mental system is provided above all by the fundamental structural model of psychoanalysis, which has been formulated for about 100 years[20]. In this conceptual framework, the ego has to manage the immediate external reality and coordinate it with the inner needs, which, through the drives of the id and the imperatives of the superego, form a force field that can lead to intrapsychic conflicts. The id can be understood as the affective-motivational level of the mental in relation to the foregoing, while the superego can be seen as a set of internalized reference values (setpoints) such as norms and rules that enable a low-conflict social life[20,51]. The functions of the superego thus include the capacity for self-criticism, guilt and remorse - dispositions that are necessary for interaction with the world, the perception, processing and evaluation of new and past events or stimuli. Thus, the superego is particularly relevant for the imprinting of affectively charged content. The superego can also be understood as the relevant system of connections with the social micro-environment that embeds the person in relation to the formation of opinions, a phenomenon that is group-related (family, peer group) and that was discussed at the beginning of the article. Thus, the social environment influences the individual and, conversely, the behavior of the individual (also as uniform collective behavior) influences the social environment.

The concept that behavior towards the environment in turn determines new perceptions results in a comprehensive and fundamental feedback loop that can be fundamentally captured in a control loop model of the “situated person.” This model also corresponds to the basic conceptual structure of psychological and sociological action theory, which emphasizes the relevance of the (social) environment[52-54]. Now, in the sense of a human-ecological perspective, it is especially the social information environment of the person that matters.

Social environment - group phenomena and trust

The most important level of information about the social environment for the individual is the microsocial level of the group (family, peer group) with which relevant communications take place. As mentioned at the beginning, social security, social belonging and acceptance and similar social needs are first satisfied by the immediate social environment (e.g., the mother). Trust in others depends on these experiences, which - pychoanalytically speaking - leads to a sup-portive superego. But not only the immediate microsocial environment, but also the macrosocial level with its subsystems media, politics, science, etc determines the important feeling of social trust. Currently, however, social trust is declining in some countries, which can be partly attributed to the non-acceptance of limits and limitations of the competences of the respective social institutions[55,56]. Thus, the acceptance of the limits of the epistemological options of science is crucial for a knowledge society: Science can only approach the truth, be it through empirical methods or (social) constructivist theoretical concepts, and it must be accepted (and publicly communicated) that science must always deal with the “known unknown.” If these limitations are not communicated publicly, and if empirical relativizations of the state of science occur in the medium term, public trust in science can decline. Such (intertemporal) inconsistencies exacerbate the already fragmented (or “psychotic”) social situation and favor the formation of science-skeptical groups, reinforced above all by social media. A psychoanalytic view helps us to shed light on these processes on the social level: On the one hand, the fear of the overwhelming power of institutions feeds the need to restore a (fantasized) unbridled omnipotence (Narcissism), derived from the longing for paternal protection due to infantile helplessness. On the other hand, fears can lead to further regressive phenomena. At the macro- and micro-social level, the pandemic situation revealed well-known group phenomena in crisis, such as fragmentation and splitting, which are basically regression to familiar previous defense functions, when normal adaptive affective-cognitive processing is overwhelmed. Sublimation, for example, as a defense fails when one's own body becomes the source of suffering.

Back to the corona crisis: In pandemic situations, restrictive macrosocial conditions hinder the microsocial processing of narratives with the personal social environment and disrupt people’s psychosocial climate, relationships with the real world and the information world. Over the course of the three Corona years, the distal macrosocial and proximal microsocial worlds lost their consensual foundations, which can lead to cognitive stress in every single social interaction, thus becoming chronic. Proponents and supporters of the respective Corona policy, but also many ambivalent and even skeptical, resistant and opposing individuals emerged. Some of them are associated with so-called conspiracy theories, and some even show an aggressive-oppositional attitude. The general negative affective consequences of the corona regulations can now be seen, for example, in hospitalization rates or (adolescent) psychiatric departments due to chronic anxiety, aggression and depression[57]. Therefore, individual interaction with a dynamically fragmented world in the event of a crisis is obviously a risk factor for extreme psychosocial reactions.

As a consequence and to return to the initial question of this text - the basic hypothesis can be put forward that differentiated but consistent conceptual frameworks of narratives, such as an understandable pandemic theory generated in the context of science as a knowledge producer, are useful for this, since theories and models generally help to bring observations into a consistent order, thereby reducing cognitive dissonances. The multi-level system-theoretical framework presented here for a graded but more comprehensive understanding of affect-relevant cognitive disorders could also contribute to this.

Benefits of a systemic understanding of the psychosocial climate on a nested collective and individual level: Theories make it possible to integrate heterogeneous information. This can also be achieved by multi-level system-theoretical models of the psychosocial situation of humans, as a variant of which was explained here on the basis of the Corona pandemic. In context of the field of theoretical public health such “(socio) ecological models” have a long tradition[58-61]. Such models, however, must also be rooted in the anthropological perspective of the “situated experiencing person” conceived as a bio-psycho-social being[62]. This view is therefore characteristic of a human-ecological theory[17,36,62-64]. As already mentioned at the beginning, human ecology aims at such nested multi-level, multifunctional and multi-sector models, which basically strive for a differentiated concept of the environmental relations of the person and also a differentiated concept of the mental. These models thus capture the external relations of men to the environment and at the same time the internal model of the internalized environment (Supplementary material, ecological psychology), which also refers to the self-image (cf. object relations theory)[31]. In this view, on one level the person must relate environmental offers and personal needs, but also on another level she must weigh up the requirements of the environment with regard to the person’s competences to meet these requirements. However, this ultimately four-pole basic constellation of the human-environment relationship system very often leads to chronic conflicts. In the case of the Corona pandemic, for example, people had to reduce exposure behavior to other people (avoiding contact, distancing, wearing masks), but at the same time maintaining contact with important people, which led to conflict.

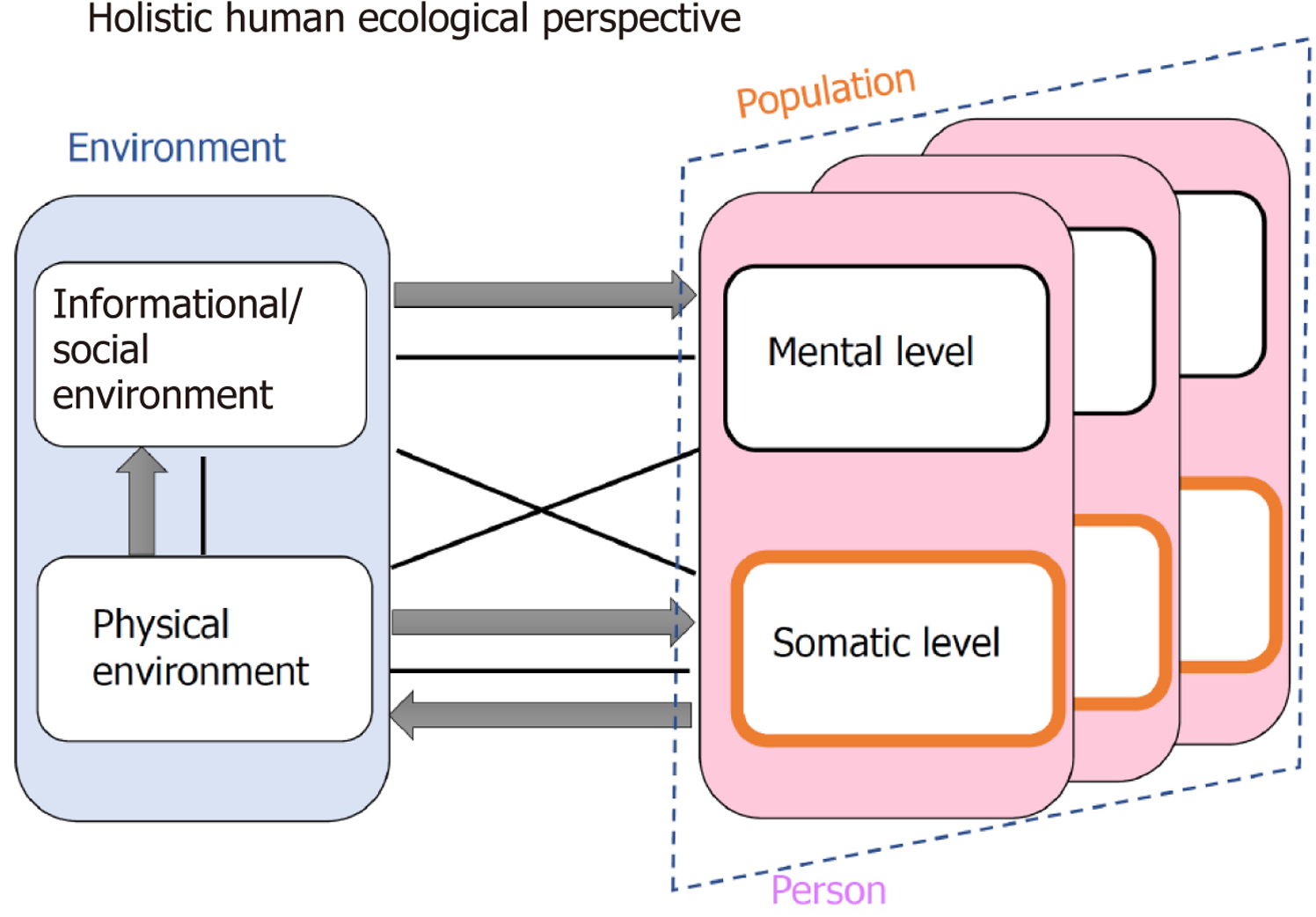

In this way, the macro version of this integrative model thus fundamentally captures that events in the natural environment (e.g., the coronavirus or climate change) affect the health of the population (ecosystem health), which is dealt with by institutions of society (e.g., science as a specialized social system), for example insofar as this knowledge and corresponding plans for problem management may be passed on via mass media and under political control. The model also captures that in the next phase people change their attitudes and behavior (e.g., wear masks or reduce the consumption of non-renewable energy), and finally there is a better situation in the population and so the measures as in the transition from pandemic to endemic can be relaxed (Figure 3).

Figure 3 A socioecological framework of health with interlinked conceptual building blocks (see text): In relation to pandemics, the virus acts as part of the physical environment at the somatic level of the person/population (horizontal grey arrow, bottom).

This process is captured by science as a subsystem of society (vertical grey arrow), and this information is communicated to the population via media (horizontal grey arrow, top), which changes the exposure behavior of the population (horizontal grey arrow).

It is helpful in this basic modeling to distinguish two levels of interactions – an informational level and a material level: the virus affects humans directly and materially, but invisibly, and in some cases causes severe COVID-19 diseases. This can be observed by science and this information can be passed on to the entire population (Figure 3). Such a model type could therefore expand the theoretical field of public health as a form of “social health ecology” devoted to health-related nature-society-human interactions (eco-socio-psycho-somatics) and could also be incorporated in a simplified form into narratives of health promotion and prevention.

In this model, language, as used in society, plays a crucial role in describing, evaluating and effectively communicating scientific observations to the public. And this brings us back to our initial question: The communicated texts should make sense through their conceptual framework and thus be able to calm emotions. In this respect, they are also “narratives” in the strict sense of the word.