Published online Jan 19, 2022. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v12.i1.169

Peer-review started: April 27, 2021

First decision: June 17, 2021

Revised: July 18, 2021

Accepted: November 26, 2021

Article in press: November 26, 2021

Published online: January 19, 2022

Depression is recognized as a major public health problem with a substantial impact on individuals and society. Complementary therapies such as acupressure may be considered a safe and cost-effective treatment for people with depression. An increasing body of research has been undertaken to assess the effectiveness of acupressure in various populations with depression, but the evidence thus far is inconclusive.

To examine the efficacy of acupressure on depression.

A systematic literature search was performed on PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, Embase, MEDLINE, and China National Knowledge (CNKI). Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) or single-group trials in which acupressure was compared with control methods or baseline in people with depression were included. Data were synthesized using a random-effects or a fixed-effects model to analyze the impacts of acupressure treatment on depression and anxiety in people with depression. The primary outcome measures were set for depression symptoms. Subgroups were created, and meta-regression analyses were performed to explore which factors are relevant to the greater or lesser effects of treating symptoms.

A total of 14 RCTs (1439 participants) were identified. Analysis of the between-group showed that acupressure was effective in reducing depression [Standar

The evidence of acupressure for mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms was significant. Importantly, the findings should be interpreted with caution due to study limitations. Future research with a well-designed mixed method is required to consolidate the conclusion and provide an in-depth understanding of potential mechanisms underlying the effects.

Core Tip: Acupressure is effective on mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms. However, no confirmed evidence is available about the impacts of acupressure on patients with severe depressive disorders. This is the first study investigating the impacts of acupressure on depression among clinical and general populations.

- Citation: Lin J, Chen T, He J, Chung RC, Ma H, Tsang H. Impacts of acupressure treatment on depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry 2022; 12(1): 169-186

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v12/i1/169.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i1.169

Depression is a prevalent and debilitating mental disorder that is estimated to affect more than 264 million people worldwide[1]. Individuals with depression commonly experience dysfunctional symptoms, including undesirable mood, impaired concentration, poor quality of sleep, and a high risk of suicide. Up to 15% of clinically depre

In primary care, subthreshold and mild depression are most often managed with psychological interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapies, interpersonal therapy, and psychological counseling. Antidepressant medication is usually prescribed for moderate-to-severe depression[6]. However, medications are associated with drug dependence and side effects, which negatively impact adherence. Psychological therapies require considerable time and resources, resulting in high drop-out rates and unsustainable effects. Surveys have shown that self-help and complementary therapies for depression were extensively reported[7,8].

Acupressure is a non-invasive complementary and alternative technique that shares common characteristics with acupuncture[9]. It is defined as the stimulation on acupuncture points located along meridians (also known as “acupoints”) using fingers, hands, knuckles, or dull instruments to exert pressure, leading to a sensation of soreness, numbness, and distention[10]. According to the core concept of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) theory, acupressure stimulates the meridian. It restores health by balancing the “qi” flow, which could be described as bioenergy[11]. Results from studies of acupuncture have suggested that effects on neurotransmitter levels of serotonin and noradrenaline may be one of the potential mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects. On the other hand, the pressure exerted on the acupoints regulates the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems to create feelings of calm and relaxation[12].

Acupressure has received increased attention for the alleviation of pain or discomfort associated with physical illnesses, injuries, and surgical operations in different populations, ranging from children[13] to the elderly[14]. Furthermore, the benefits of acupressure in psychological well-being have also been observed. While emerging evidence shows that acupressure has encouraging and promising effects on depression[15,16], there has been no systematic review and meta-analysis of its effectiveness for this condition. The present study aimed to synthesize findings of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and quantify the effectiveness of acupressure for the treatment of depression in adults. Moreover, selection of acupoints and manipulation techniques, adverse events, drop-out rates, and quality of the included RCTs are described for treatment decision-making.

This systematic review and meta-analysis were performed according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement guideline.

The following electronic databases were systematically searched until December 2020: PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, Embase, MEDLINE, and China National Knowledge (CNKI). The main keywords used were “acupressure” OR “finger massage” OR “acupoint massage” OR “shiatsu” AND “depress*” OR “mental health” OR “mental disorder*” OR “psychiatric disorder*” OR “mood disorder*” OR “bipolar disorder.*” Reference lists of retrieved studies and review articles were screened for additional references.

We screened the studies in two phases. First, two review authors (He J and Chen T) independently screened the titles and the abstracts. Second, the full text of potentially eligible studies was retrieved and assessed independently by the same two authors. Any disagreement between the review authors was resolved by a third review author (Lin J).

Inclusion criteria were defined using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes)[17]: (1) Were clinical trials, including RCTs and non RCTs that included acupressure as one of the study groups; (2) Used acupressure as the sole intervention compared with the control condition of either sham control or standard control (e.g., standard care); (3) Used a sample of participants aged 18 years old or above; and (4) Were published in either English or Chinese.

Studies were excluded: (1) If they did not target depression as one of the outcome measures before and after acupressure intervention; or (2) If they used acupressure as part of a multi-component intervention.

All data were extracted from studies by two review authors (He J and Chen T) according to predefined criteria, including: (1) The first author, year, and country of publication; (2) The number and characteristics of the participants; (3) The regimen of the experimental and control interventions; (4) The manipulation techniques of acupressure; (5) Drop-out rate; (6) Baseline depressive symptoms, and (7) Outcome measures. For the purpose of this review, our primary outcome was the change of depressive symptoms before and after an intervention. That was evaluated using any standardized clinical measures, including Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS), Major Depression Inventory (MDI), and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). The anxiety level, manipulation, and frequency of acupressure, drop-out rate, and adverse events were reported as the secondary outcomes. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by consensus decision.

The quality of reporting for the acupressure trials was evaluated independently by two authors (He J and Chen T) using revised STRICTA (Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture). A total of 10 items were applicable to the acupressure studies, which covered acupressure rationale, pressure details (instead of needling details), treatment regimen, other components of treatment, practitioner background, and control intervention[18]. The acupressure procedure was considered well-reported if at least six out of the ten STRICTA items were reported.

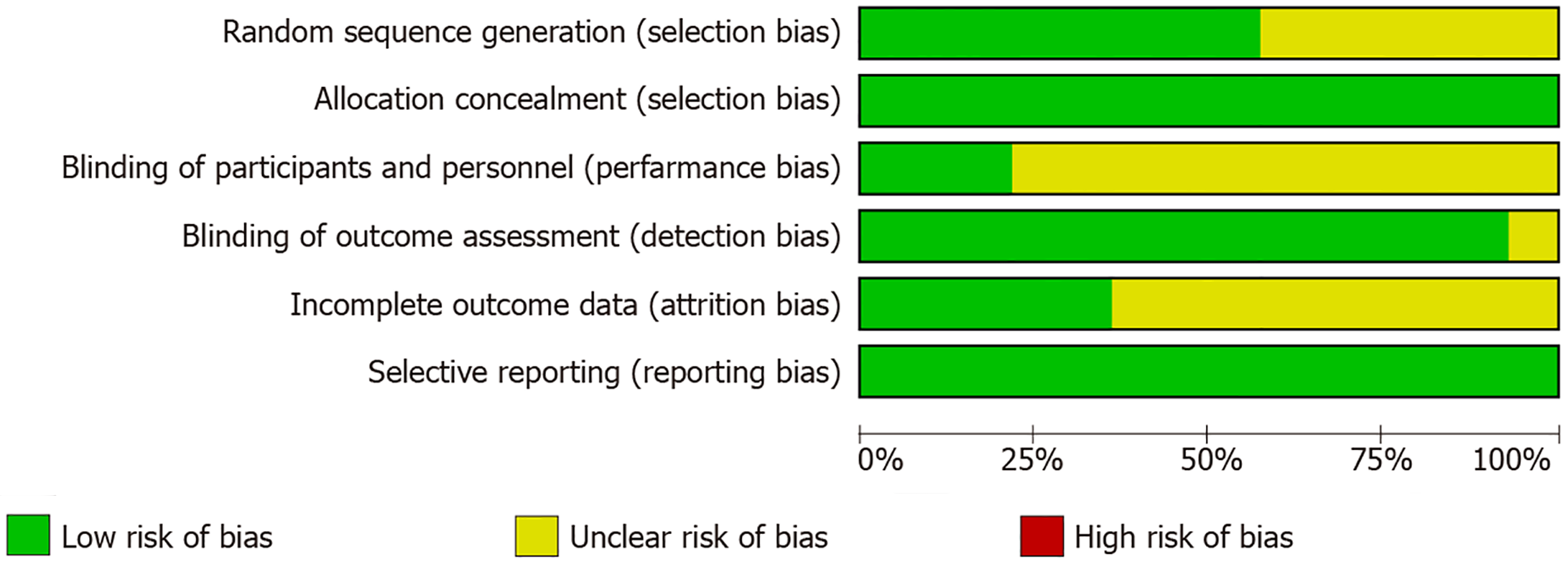

The methodological quality of identified studies was assessed according to the six domains in the Cochrane risk of bias tool. These are random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting. Each domain was rated as “high” (seriously weakens confidence in the results), “unclear,” or “low” (unlikely to significantly alter the results). Given the nature of the intervention, it was difficult to blind the personnel who applied the acupressure, so only the participants and outcome assessors were blinded. To follow the guidelines recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group, a compliance threshold of < 50% of the criteria was associated with bias[19]. Studies that met at least four domains with no serious flaws were considered as having a low risk of bias. If necessary, attempts were made to contact authors to obtain additional information.

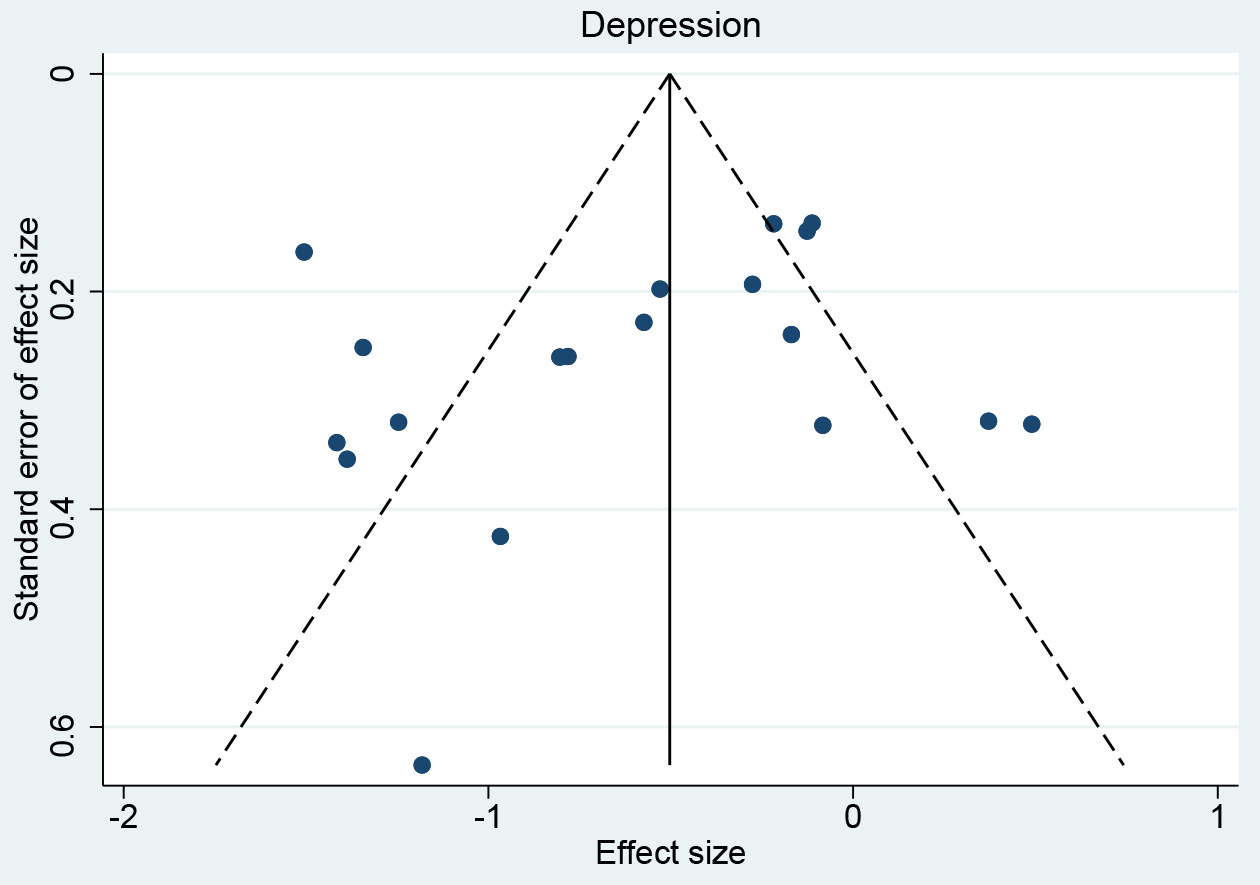

Funnel plots were constructed to assess the risk of publication bias across series for all outcome measures. The Egger regression was used to test the asymmetry of the Funnel plots, with P > 0.1 indicating no publication bias.

According to Jackson & Turner[20], meta-analysis was performed when at least five studies with similarities in clinical characteristics and with no domain rated as having a high risk of bias were included. Meta-analyses were conducted using the changes of the scores between pre- and post-intervention measured by different scales. Heterogeneity among studies was evaluated by calculating the I2 statistic and χ2 test (assessing the P value) using Review Manager 5 software (V5.4, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen). If the P value was < 0.05 and I2 > 50%, we considered the heterogeneity to be substantial. A random-effect model was used to combine the data if significant heterogeneity existed. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) with 95%CI were used for continuous outcomes. The magnitude of the overall effect size was calculated based on the pooled SMD. Following Cohen’s categories, the effect sizes of 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 were considered small, medium, and large, respectively[21].

Sensitivity analyses and subgroup analyses were performed to investigate the effects of acupressure with different study designs, ages of participants, control conditions, and treatment duration. Meta-regression was also performed to identify the potential predictors of the effects of acupressure on depression.

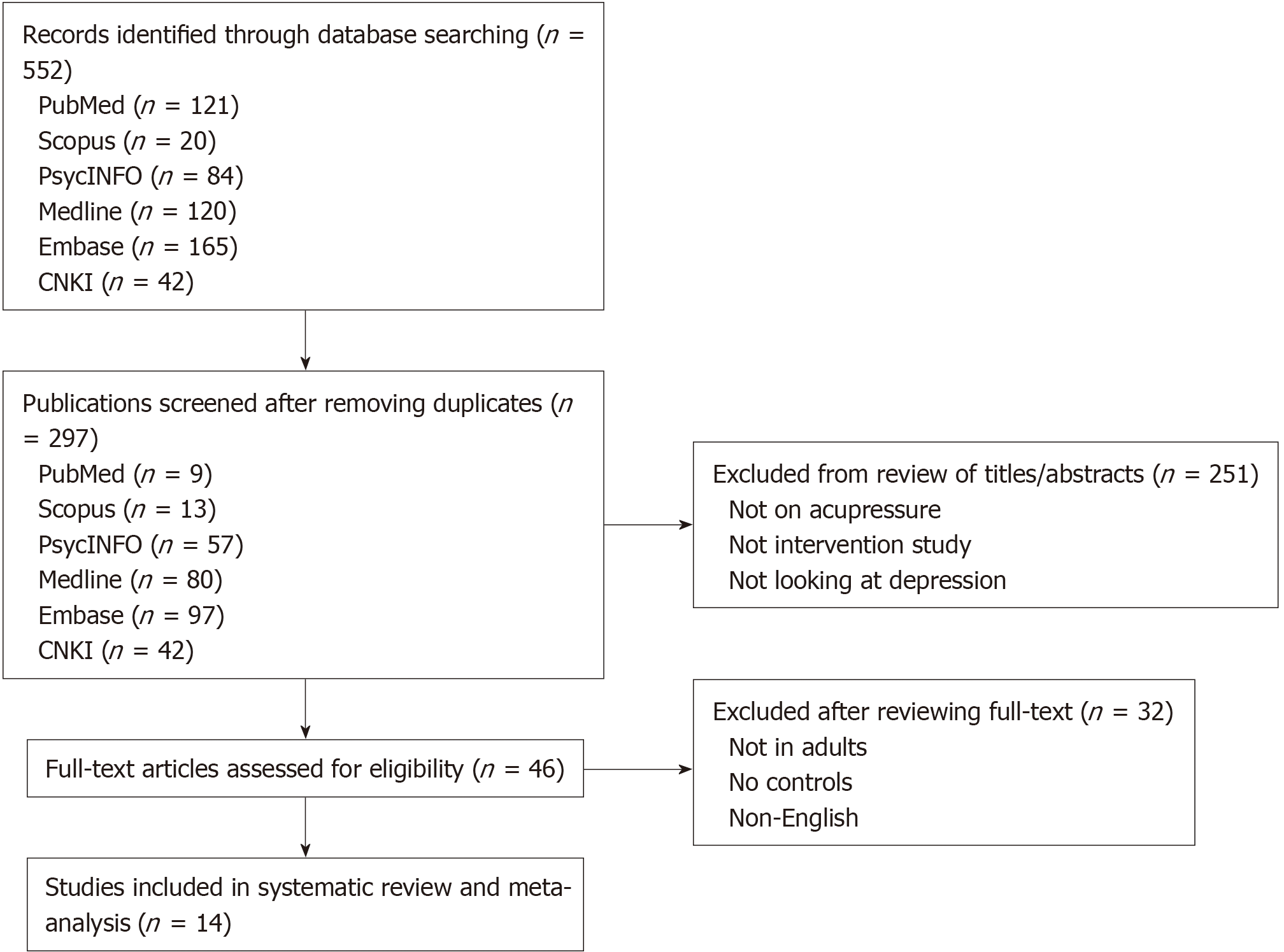

A PRISMA flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. The search initially found 552 articles. After screening the title and abstract, 46 of which were examined full text. Of these, 16 were excluded based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and 16 Chinese articles were excluded due to their low quality, resulting in a total of 14 eligible articles for systematic review. There was no publication bias based on the Funnel plots and Egger-regression test results (Figure 2). Fourteen RCTs involving 1439 participants were included for meta-analyses.

The main characteristics of the included studies are described in Table 1. The sample size of the 14 studies varied from 12 to 288. Four studies focused on old participants (aged 65 or above)[22-25], while the remaining studies recruited participants from 20-64 years. Ten studies recruited participants with chronic diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[22], lung cancer[26], acute myocardial infarction[27], breast cancer[28], low back pain[29], multiple sclerosis[30], hemodialysis[31-33], and unilateral knee osteoarthritis[34]. Three studies recruited patients with depression[24,25,35]. One study was for patients with Alzheimer’s disease comorbided with depression[23]. None of them included patients with major depressive disorders (MDD), and the overall severity of depressive symptoms in the participants was mild to moderate. The drop-out rate ranged from 0 to 28.8%, with a mean of 10.2%.

| Ref. | Type of study | Participants (sample size, mean age ± SD) | Drop-out rate, n (%) | Treatment (frequency and duration) | Manupilation techniques (acupoints composition, and techniques used) | Control | Depressive symptoms at baseline M (SD) | Outcome measures |

| Bergmann et al[27], 2014 | RCT | Acute myocardial infarction with PPS acore ≥ 60 (213, 61.0 ± 8.1) | 32 (15.0) | Acupressure (45 min twice a day for 12 wk) | Figure pressure on two points at the sternum | Treat as usual (TAU) | MDI: 8.9 (7.4), PPS: 81 (13) | MDI, QOL, WHO-5’s well-being index, PPS |

| Dehghanmehr et al[31], 2020 | RCT | Hemodialysis with no severe depression and anxiety (60, 39.2 ± 11.32) | 0 | Acupressure (8 min, 3 d weekly for 4 wk) | Figure pressure on acupoint Saiyinjiao | Sham, TAU | BDI: 31.44 (20.95), STAI: 47.60 (7.04) | STAI, BDI |

| Hmwe et al[32],2015 | RCT | Hemodialysis with depressive symptom (108, 58.06 ± 11.4) | 0 | Acupressure (12 min per session, 3 sessions weekly for 4 wk) | Figure pressure on acupoints Yintang, Shenmen, and Taixi | TAU | DASS depression: 10.93 (8.38), GHQ total: 25.33 (12.56) | DASS, GHQ-28 |

| Honda et al[35], 2012 | RCT | College students with depressive symptoms (25, 33.2 ± 10.0) | Not mentioned | Acupressure (30 seconds per session, 3 sessions daily for 4 wk) | Figure pressure on six points on the neck (three points on the left and right side each) | TAU | BDI: 55 (10) | BDI |

| Kalani et al[33], 2019 | RCT | Hemodialysis with BDI score ≥ 10 (96, 53.4 ± 13.9) | 0 | Acupressure (18 min per session, 3 sessions weekly for 4 wk) | Figure pressure on acupoints Sanyinjiao, Zusanli, Yanglingquan, Yongquan, Shenshu, and Shenmen | Sham, TAU | BDI: 27.5 (9.1) | BDI |

| Lanza et al[23], 2018 | RCT | Alzheimer with CDR score ≤ 2 (12, 80.0 ± 9.0) | 0 | Acupressure (40 min weekly for 40 wk) | Figure pressure on relevant trigger points of the meridians | TAU | GDS: 13 (2) | GDS, MMSE, ADL, IADL |

| Molassiotis et al[24], 2020 | RCT | Depression with GDS score ≥ 8 (118, 79.5 ± 14.5) | 34 (28.8) | Acupressure (5 min per session, twice weekly for 12 wk) | Figure pressure on acupoints Zusanli, Zhongfu, Shenmen, Taichong, Baihui | Sham, TAU | GDS: 10.6 (2.1), GHQ: 18.8 (5.9) | GDS, PSQI |

| Rahimi et al[30], 2020 | RCT | Multiple sclerosis with EDSS score = 0-5.5 (106, 20-45 years old) | 20 (18.9) | Acupressure (15 min every day for 4 wk) | Figure pressure on acupoints Shenmen and Yintang | Sham | DASS depression: 11.48 (3.1) | DASS, FSS |

| Rani et al[34], 2020 | RCT | Knee osteoarthritis with Kellgrene Lawrance scale grade 2 or 3 (212, 58.07 ± 11.22) | 11 (5.2) | Acupressure (15 min per session, 2 sessions per day, 5 d weekly for 32 wk) | Figure pressure on acupoints Liangqiu, Dubi, Zusanli, Yinglingquan, Xuehai, Yanglingquan | TAU | DASS depression: 14.56 (8.63) | DASS, VAS, GHQ-12, BMSWBI, WHOQOL-BREF |

| Tang et al[26], 2014 | RCT | Lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy (40, 64.4 ± 9.2) | 10 (25) | Acupressure (3 min once every morning for 20 wk) | Figure pressure on acupoints Hegu, Zusanli, and Sanyinjiao | Sham | HADS: 7.29 (4.39), ECOG-PSR: 11 (45.8) | HADS, TFRS, ECOG-PSR, PSQI |

| Tseng et al[25], 2020 | RCT | Depression with GDS score > 5 (47, 82.78 ± 6.88) | 8 (17.0) | Acupressure with a magnetic bead (7 d weekly for 2 wk) | Magnetic bead on ear Shenmen point | Sham | GDS: 8.71 (2.31) BAI: 13.63 (7.36) | GDS, BAI |

| Wu et al[22], 2007 | RCT | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with depressive symptom (44, 73.0 ± 9.7) | 0 | Acupressure (16 min per session, 5 sessions weekly for 4 wk) | Figure pressure on acupoints Dazhui, Tiantu, Shousaili, Feishu, Shenshu | Sham | GDS score at basline not available | GDS, DVAS |

| Yu et al[29], 2020 | RCT | Postpartum wome with low back pain score ≥ 1 (70, 34.4 ± 4.8) | 0 | Acupressure (10 min per session, 5 sessions weekly for 4 wk) | Figure pressure on acupoints Shenhu, Dachangshu, Guanyuanshu, Weiyang, and Sanyinjiao | Sham | EPDS: 9.4 (4.5) | EPDS, RMDQ, ODI, VAS |

| Zick et al[28], 2018 | RCT | Breast cancer with depressive symptom (288, 60.5 ± 10.0) | Not mentioned | Acupressure (30 min every day for 10 wk) | Figure pressure on acupoints Hegu, Zusanli, Sanyinjiao, Taixi, Baihui, and Qihai | Sham, TAU | HADS: 6.2 (3.2) | VAS, BPI |

Table 2 describes the standards of reporting for the included trials. The standards reflect the revised STRICTA criteria (2010). All studies reported the frequency of treatment, the setting and context of intervention, and the control condition. Only one study did not mention the rationale of acupressure[27]. Three studies did not report the acupoints used in the intervention[23,27,35]. All studies provided a detailed description of the method/materials used for acupressure. All studies except two[23,25] specified the duration of pressure retention. Two studies reported other compo

| Acupressure details | Other components of treatment | |||||||||

| Ref. | Acupressure rationale | Acupoints used | Materials used for acupressure | Frequency of acupressure | Acupressure retention | Description of method/materials used for acupressure | Other components | Setting and context | Practitioner background | Control intervention |

| Bergmann (2014) | NR | NR | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y |

| Dehghanmehr (2020) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | NR | Y |

| Hmwe (2015) | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | NR | Y |

| Honda (2012) | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y |

| Kalani (2019) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | NR | Y |

| Lanza (2018) | Y | NR | NR | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y |

| Molassiotis (2020) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | NR | Y |

| Rahimi (2020) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y |

| Rani (2020) | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y |

| Tang (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Tseng (2020) | Y | Y | NR | Y | NR | Y | NR | Y | NR | Y |

| Wu (2007) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y |

| Yu (2020) | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | NR | Y |

| Zick (2018) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y |

Risk of bias was assessed and summarized in Figure 3. Fourteen studies were described as “randomized,” of which eight studies reported detailed randomization methods[25,26,28,30-34]. All studies reported allocation concealment in detail. Blinding of outcome assessments was sufficiently carried out in 13 studies, with only one study providing no detailed description[26]. Five of them expressly stated a completion rate of their participants and were at low risk of attrition bias[22,24,26,27,34], while the others gave no details of missing data. All studies presented the outcomes clearly and were rated as having a low risk of selection bias. Overall, all studies were rated low in at least four domains, and therefore, were considered as having low risk of bias.

Among the included studies, five of them applied three acupoints or fewer[25,26,30-32], and six studies applied more than three acupressure points[22,24,28,29,33,34]. However, three studies did not report the specific acupoints used for the intervention[23,27,35]. The most used acupoints were Zusanli, Sanyinjiao, and Shenmen.

All studies mentioned that selection of acupoints was based on the TCM principles and aimed to improve the body’s natural self-healing capacity by regulating and balancing Qi. Three studies[22,24,29] selected the acupoints based on a thorough literature review of the effects of acupressure on depression. Hmwe et al[32] reported that two TCM specialists from local universities had reviewed the selection of acupoints.

The duration of acupressure interventions varied across studies. They ranged from 5 s to 4 min on each acupressure point and from 30 s to 45 min per session, with an average of 15-20 min per session in most studies. The study duration ranged from 2 wk[25] to 40 wk[23]. All studies applied acupressure with finger pressure, except one study which applied the magnetic bead at relevant points[25].

The background of the therapists delivering acupressure differed in the included studies: Two trials involved research personnel[22,26], two trials employed allied health professionals[27,35], and three trials involved an acupuncturist[28,33,34]. Either “sham” or “treat as usual” (TAU) were used as controls. Nine studies employed sham stimulation that located around the true acupoints and were irrelevant to the treatment of depression[22,24-26,28-31,33]. Four studies had both a sham and a TAU control group[24,26,28,33]. The other studies used TAU as the control group.

Three trials adopted BDI[31,33,35]; four trials adopted GDS[22-25]; two trial used HADS[26,28]; three trials used DASS[30,32,34]; one trial used MDI[27], and the other trial used EPDS for depression[29]. Similar findings were reported in all studies that the acupressure group had a greater reduction in depression after treatment than the sham or the TAU control groups.

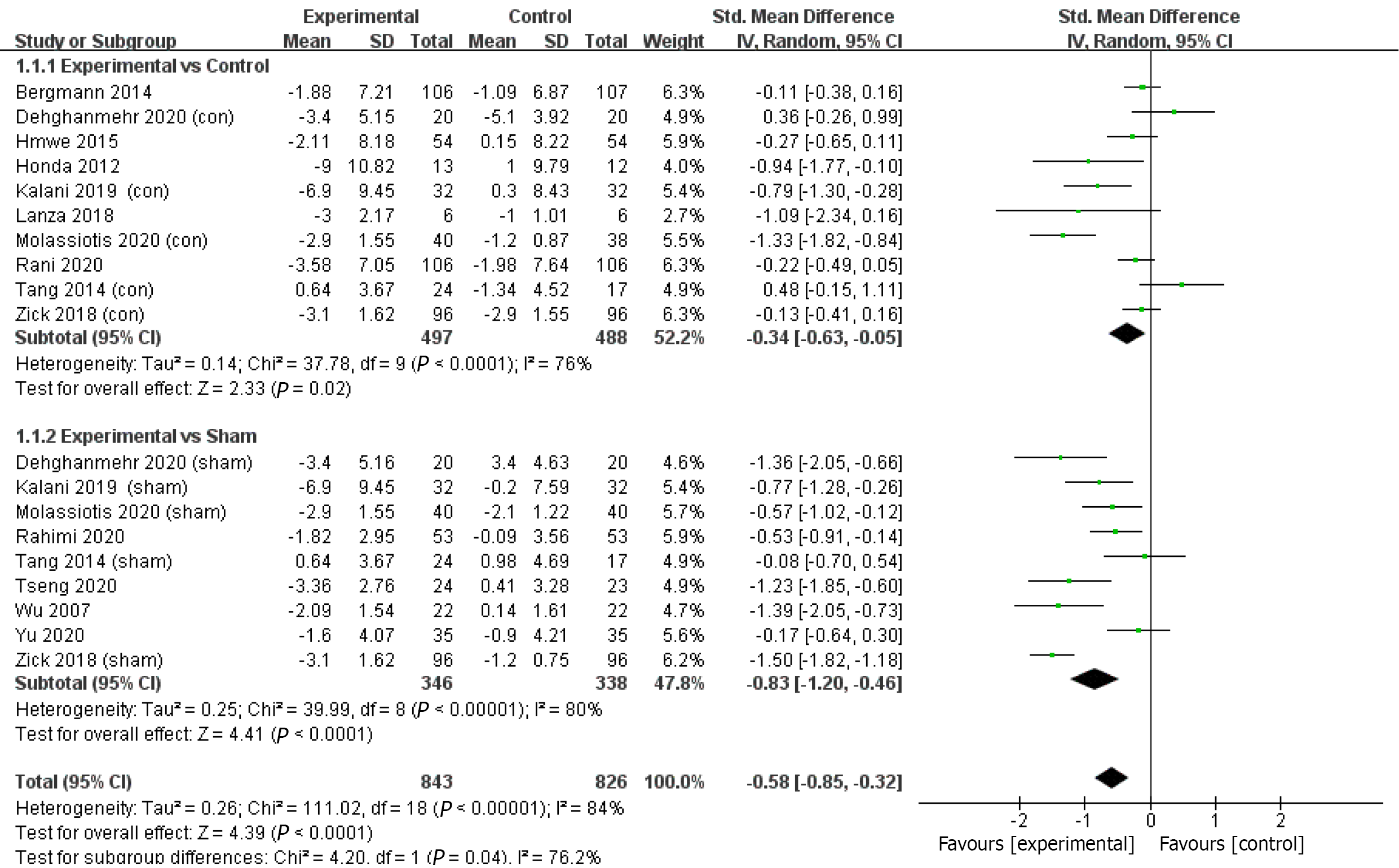

Meta-analysis of these 14 RCTs suggested a lager overall improvement in the depression level in the acupressure group than sham or TAU control groups (SMD = -0.58; 95%CI = -0.85 to -0.32; P < 0.0001; I2 = 84%; χ2 = 110.96; P < 0.0001) (Figure 4). The combined effect size was 4.39, which equals to a small effect size according to Cohen’s categories.

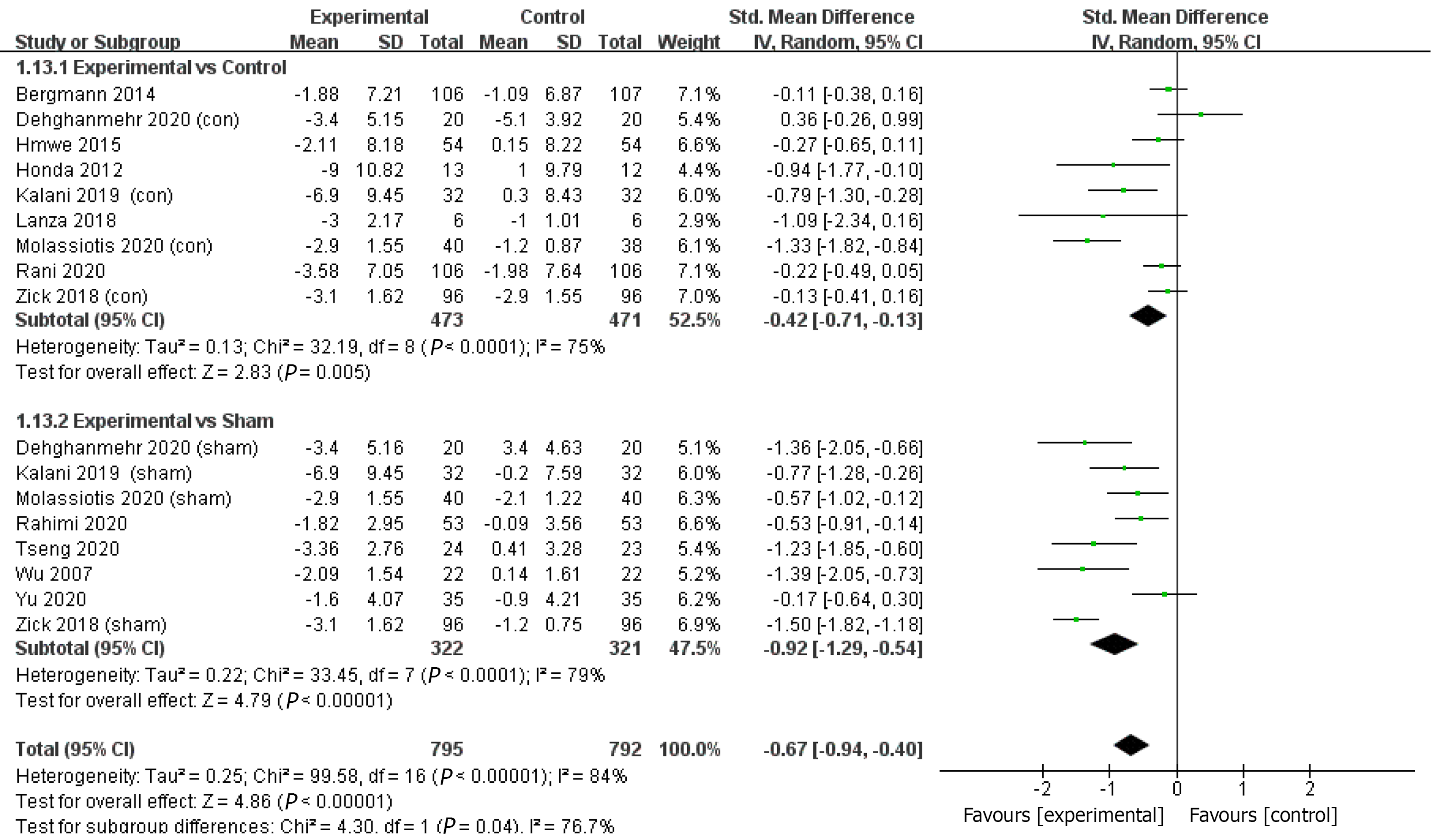

Subgroup analyses were performed in studies using different control groups (Figure 4). The combined results of 10 studies using TAU control groups showed a greater reduction in depression level in the acupressure group with a small effect size (SMD = -0.34; 95%CI = -0.63 to -0.05; P = 0.02; I2 = 76%; χ2 = 37.78; P < 0.00001; Z = 2.33). Similar results were shown in the nine studies using sham controls with a moderate effect size (SMD = -0.83; 95%CI = -1.2 to -0.46; P < 0.00001; I2 = 80%; χ2 =39.77; P < 0.00001; Z = 4.42).

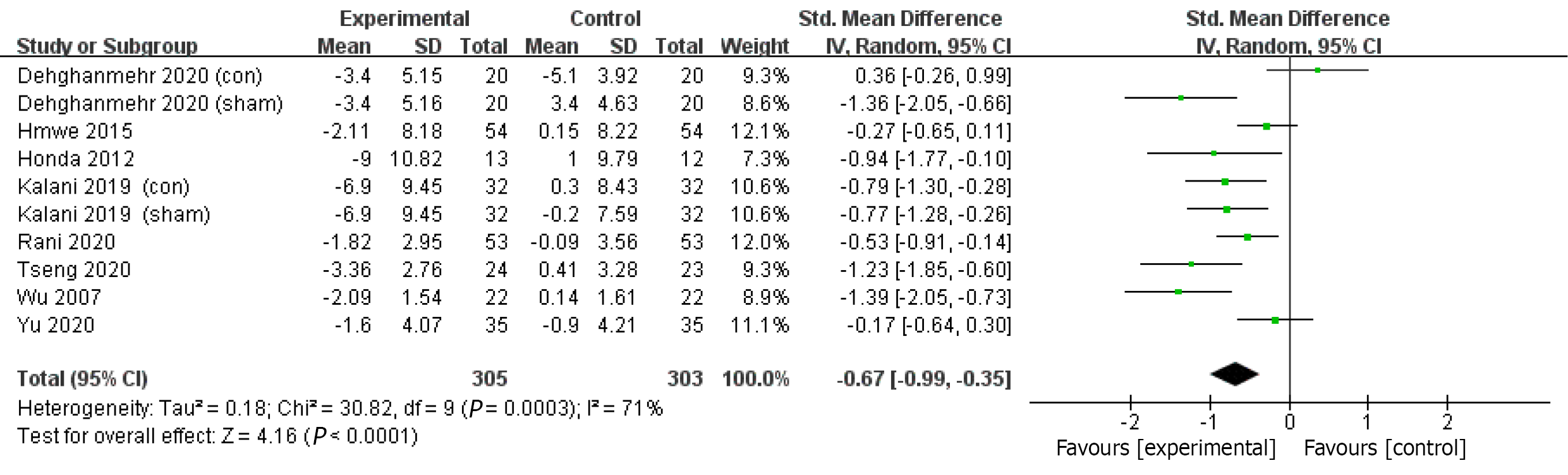

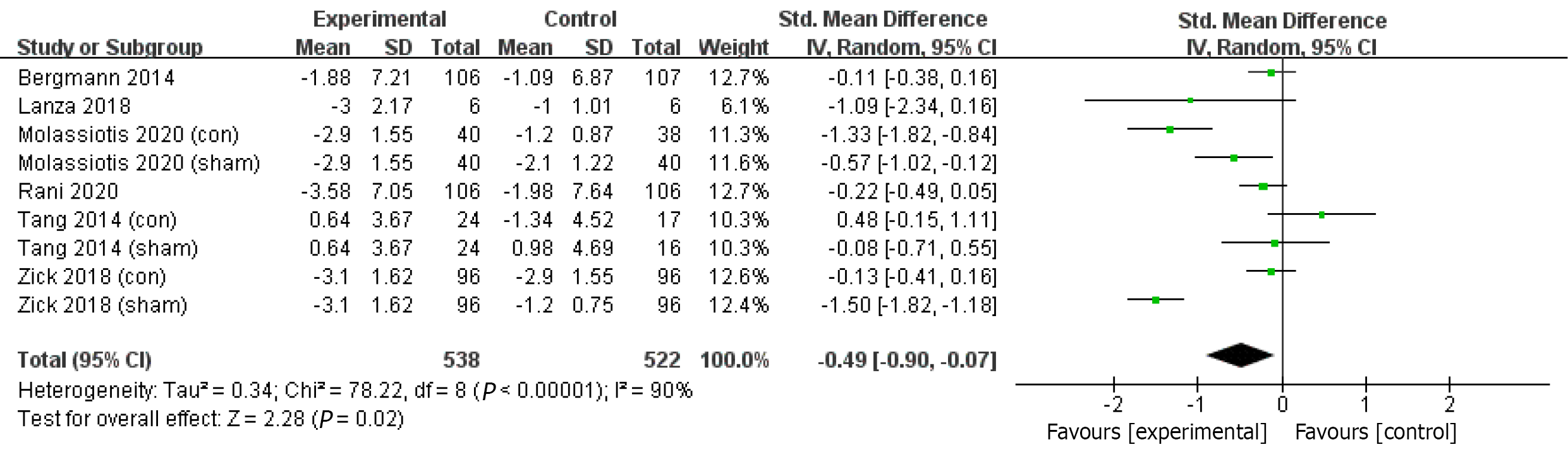

Subgroup analyses were also performed in studies with different durations. The combined results of eight studies with a duration of 2-4 wk showed acupressure significantly reduced depression levels compared to sham or TAU controls with a moderate effect size (SMD = -0.67; 95%CI = -0.99 to -0.35; P < 0.0001; I2 = 71%; χ2 = 30.82; P = 0.0003; Z = 4.16) (Figure 5). Significant reductions in the depression levels were found in six studies with a duration of more than 4 wk in the acupressure group compared to the sham or TAU controls with a small effect size (SMD = -0.48; 95%CI = -0.9 to -0.07; P = 0.02; I2 = 90%; χ2 = 78.05; P < 0.00001; Z = 2.28) (Figure 6).

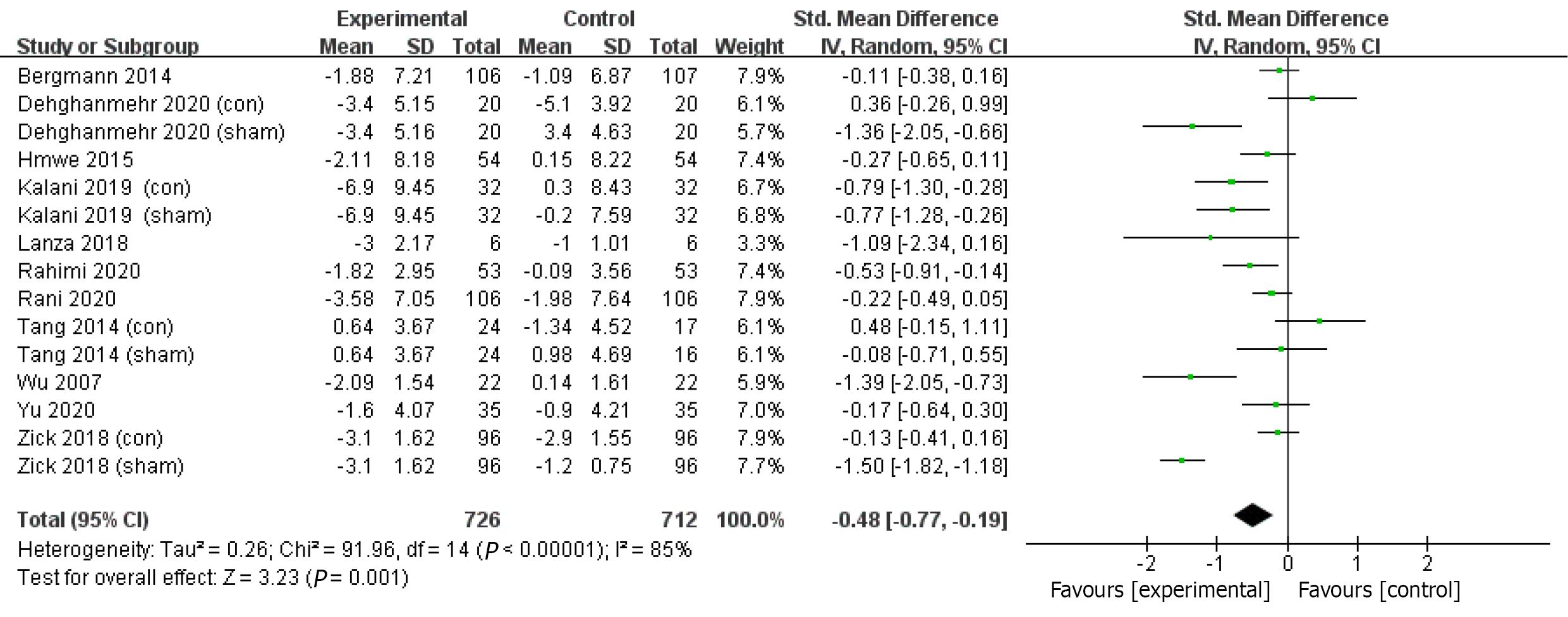

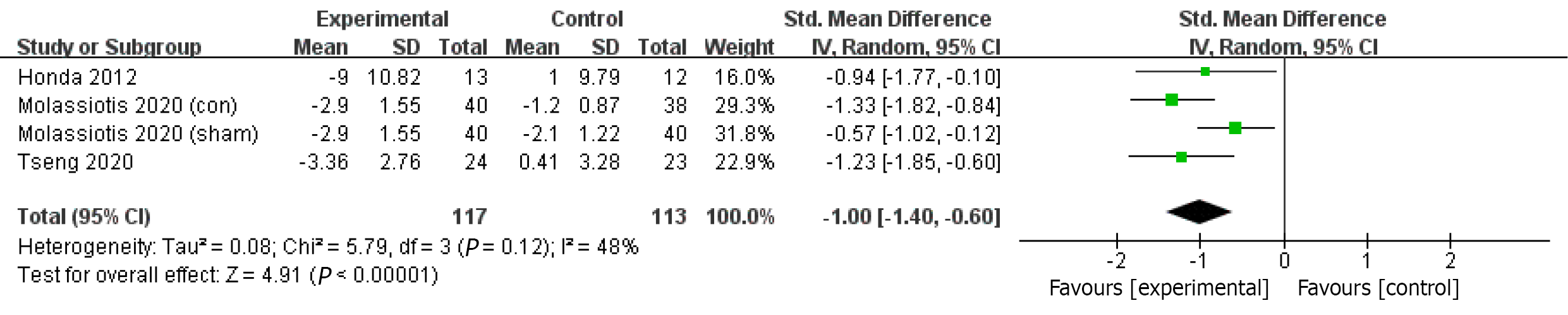

Subgroup analyses were also performed in studies with different participants. The combined results of eleven studies in participants with depressive symptoms comorbidded with chronic diseases showed acupressure significantly reduced depression level compared to sham or TAU controls with a small effect size (SMD = -0.48; 95%CI = -0.77 to -0.19; P = 0.001; I2 = 85%; χ2 = 91.96; P < 0.00001; Z = 3.23) (Figure 7). Significant reductions of depressive symptoms were also found in three studies in participants with depression with a moderate effect size (SMD = -1; 95%CI = -1.40 to -0.60; P < 0.00001; I2 = 48%; χ2 = 5.79; P = 0.12; Z = 4.91) (Figure 8).

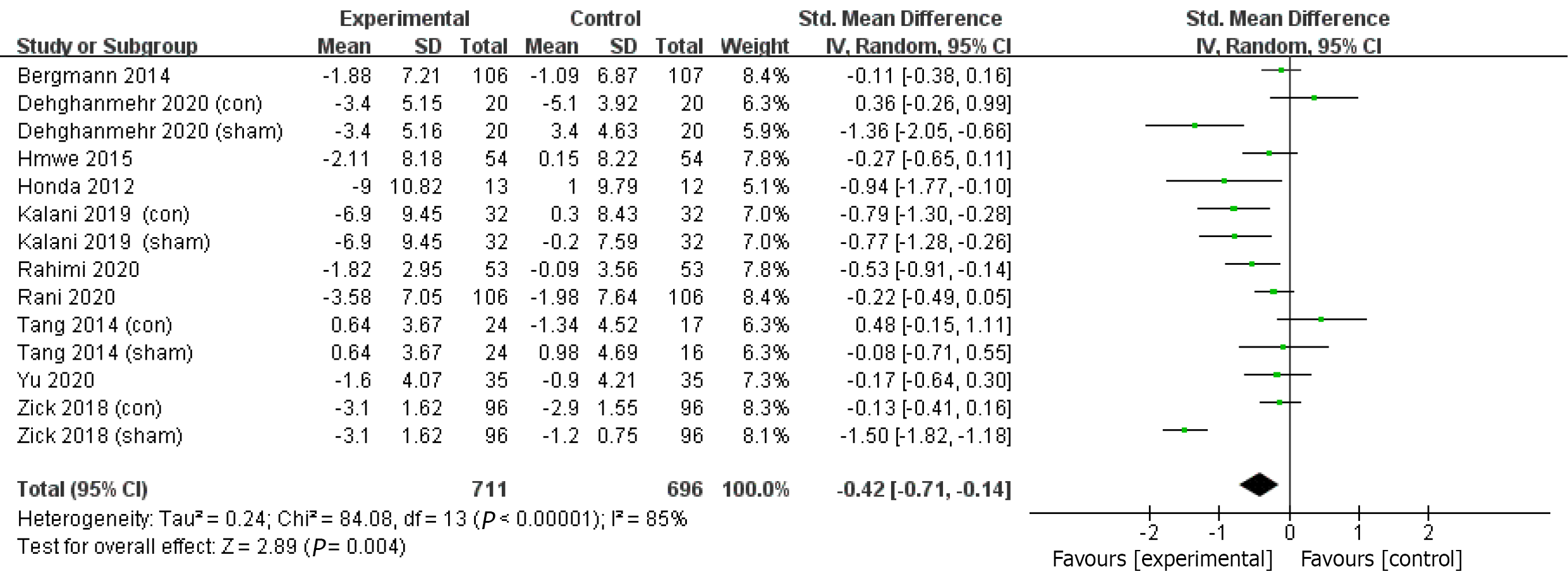

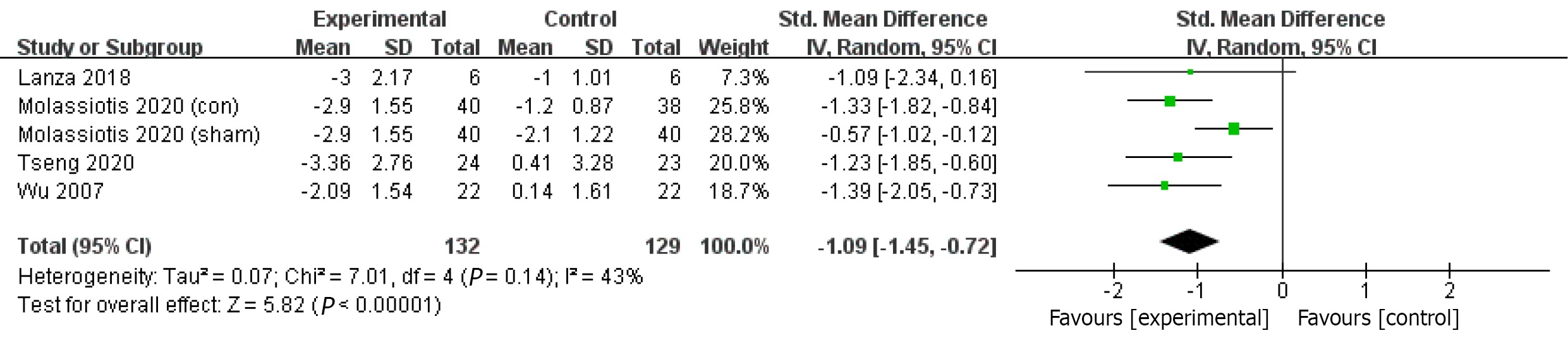

Subgroup analyses were also performed in studies with different ages. The combined results of ten studies with individuals aged 20-64 showed acupressure significantly reduced depression levels compared to the sham or TAU controls with a small effect size (SMD = -0.42; 95%CI = -0.71 to -0.14; P = 0.004; I2 = 85%; χ2 = 84.08; P < 0.00001; Z = 2.89) (Figure 9). Significant reductions in depression levels after acupressure interventions with a large effect size were also found in four studies in participants over 65 years old (SMD = -1.09; 95%CI = -1.45 to -0.72; P < 0.00001; heterogeneity: I2 = 43%; χ2 = 7.01; P = 0.14; Z = 5.82) (Figure 10).

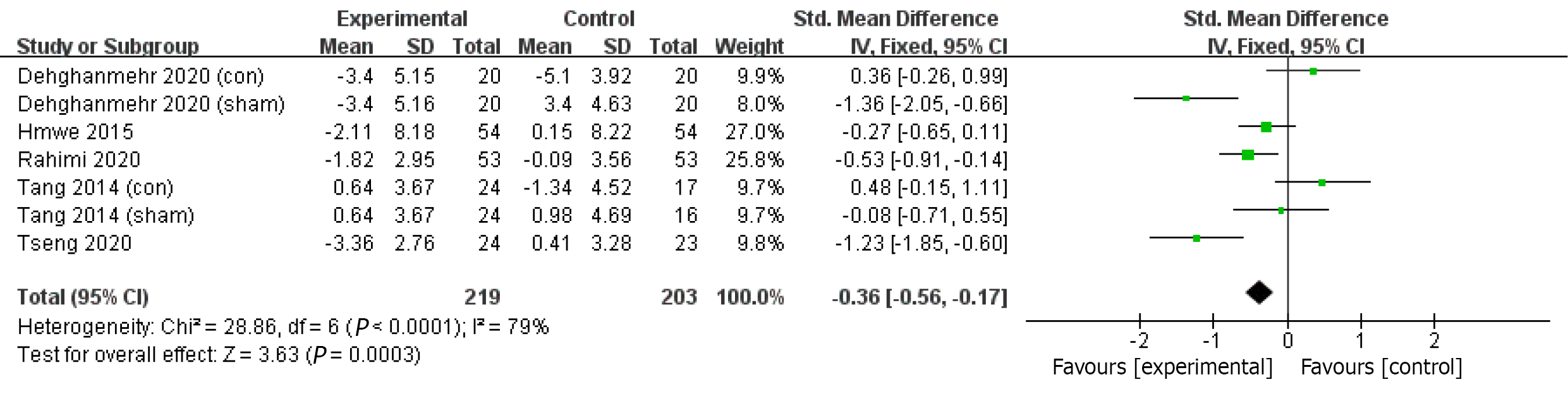

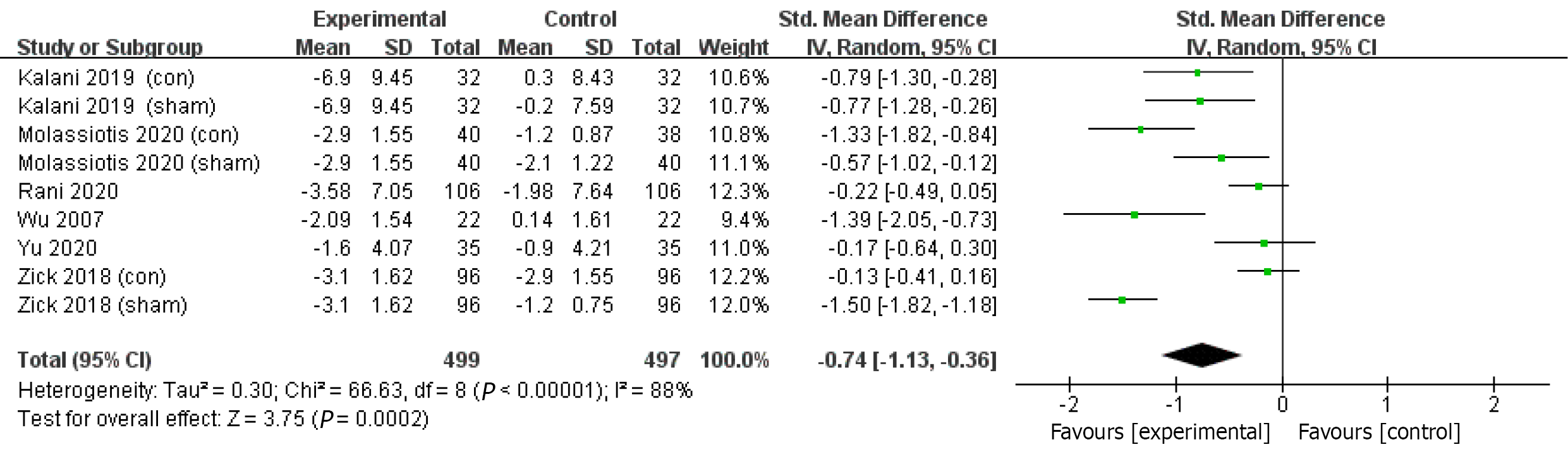

Subgroup analyses were performed in studies using different numbers of acupoints. The combined results of RCTs with no more than 3 acupoints (3 included) (SMD = -0.36; 95%CI = -0.56 to -0.17; P < 0.0001; I2= 79%; χ2 = 28.86; P = 0.0003; Z = 3.63) (Figure 11), and more than 3 acupoints showed significant effects on depression in acupressure compared to controls with moderate effects (SMD = -0.74; 95%CI = -1.13 to -0.36; P = 0.0002; I2= 88%; χ2 = 66.63; P < 0.00001; Z = 3.75) (Figure 12).

Subgroup analyses were also performed in studies using the three most used acupoints. The combined results of the studies showed significant beneficial effects on depression in the acupressure treatment group compared to controls, with a large effect size for Sanyinjiao (SMD = -0.54; 95%CI= -0.69 to -0.39; P < 0.00001; heterogeneity: I2 = 89%; χ2 = 72.17; P < 0.00001; Z = 7.03), a moderate effects size for Shenmen (SMD = -0.75; 95%CI = -1.03 to -0.47; P < 0.00001; I2= 60%; χ2 = 15.14; P = 0.02; Z = 5.20) and a small effect size for Zusanli (SMD = -0.56; 95%CI = -0.97 to -0.15; P = 0.008; I2 = 89%; χ2 = 71.65; P < 0.00001; Z = 2.67).

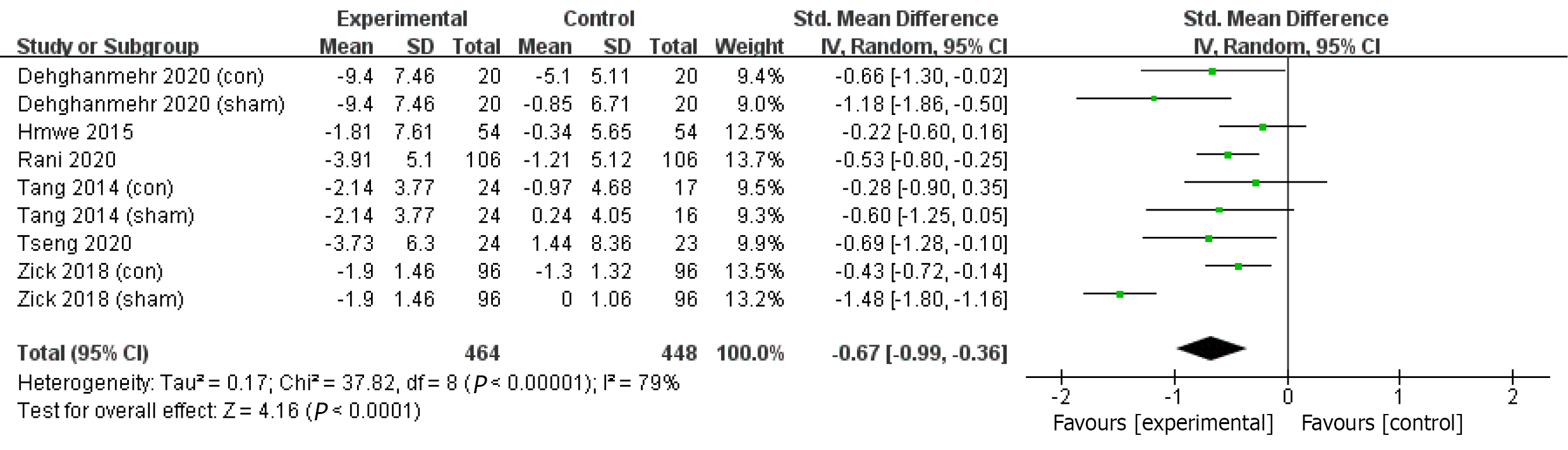

Three trials adopted HADS[26,28,31], one trial used Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)[25], and two trials used DASS[32,34] to measure anxiety level. Consistent findings were found in six studies that the acupressure group reported a greater reduction in anxiety after acupressure application than the sham or TAU controls. Meta-analyses of the six trials indicated an overall improvement in anxiety levels in the acupressure group compared with sham or TAU control groups with a small effect size (SMD = -0.67; 95%CI = -0.99 to -0.36; P < 0.0001; I2 = 79%; χ2 = 37.82; P < 0.00001; Z = 4.16) (Figure 13).

Only one study[32] reported the adverse events of acupressure during four-week acupressure in patients with end-stage renal disease, including intradialytic hypoten

Sensitivity analyses were performed after excluding one study[26], as it contained no description of blinding details. The results were similar to all the other studies involved (Figure 14).

Meta-regression analyses were performed to investigate if there were any factors associated with the effects on depression. Age, the number of acupoints used, the total time of intervention, and the physical illnesses were included to investigate if there were any associated factors with the effects on depression. However, no significant results were found.

We included in the systematic review and meta-analysis 14 RCTs with 1439 participants with depressive symptoms. Overall, the data showed that acupressure had great potential to improve mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms in both primary and secondary depression. No systematic review and meta-analysis have been performed to assess the effectiveness of acupressure on depression in various clinical population. A recent integrative review showed that acupressure reduced depression in older people in the community, whether or not they had chronic illnesses[32]. Subgroup analyses in our meta-analysis consistently showed significant reductions in depression levels after acupressure treatment for adults with a large effect size in participants aged 65 years or above. Moreover, subgroup analyses also suggested that acupressure significantly reduced depression regardless of the clinical conditions. A recent scope review of six studies indicated that acupressure improved depression and psychological health in dementia[36], which is consistent with our findings in participants with Alzheimer’s disease. However, these significant findings should be interpreted with caution due to the heterogeneity of the clinical conditions of the participants, manipulation techniques of acupressure, the selected acupoints, and the outcome measures.

Most studies in our review investigated the effects of acupressure on mild-to-moderate secondary depression in patients with chronic diseases. Three studies examined in patients with mild-to-moderate primary depression and all reported significant improvement in symptoms. However, it is not clear if acupressure is effective for patients with moderate-to-severe primary depressive disorders. Furthermore, none of the studies included in our meta-analysis mentioned specifically which symptom domains of depression were improved by acupressure treatment. Future research may focus on the effects of acupressure for moderate-to-severe depressive disorders and specific symptom domains.

Data showed a wide range of durations in acupressure interventions, ranging from 2 wk to 40 wk. More than half the studies (57.1%) involved acupressure treatment for 2-4 wk. The subgroup analyses suggested significant reductions in depression after either less than or more than 4 wk, indicating that acupressure benefits psychological well-being even after short-term treatment.

The acupressure manipulation applied in the included studies differed widely, and no confirmative conclusion could be drawn on the most effective acupressure technique. In general, 15 to 20-min sessions and 4-wk durations were commonly adopted. The majority of studies applied more than three acupoints, and the commonest acupoints used for depression are Yintang, Sanyinjiao, and Zusanli. Future research may compare the effects on depression among different acupoints to ascertain the effect of acupressure using specific acupoints. The most fundamental technique of acupressure is firm pressure on the acupoints. No included studies mentioned the amount of pressure on the acupoint, which is related to the thickness of skin, muscle, and fatty tissue at the point. The intensity of the pressure may be associated with the effect of acupressure due to the potential mechanism of stimulating the nerve systems; this needs to be clarified. Furthermore, adjusting the intensity of pressure based on the individual’s tolerance is important in clinical practice.

All studies mentioned that the selection of acupoints was based on the TCM principles of balancing the “qi” flow in the body to promote inner self-recovery abilities. However, none of the included studies measured “qi” which may be a confounding factor for the outcomes, and none of them specified the particular neuro-mechanisms underlying the selection of acupoints. According to TCM, the “qi” circulates through 12 principal meridians between different organs of the body. There are 361 acupoints distributed along the meridians, and each is associated with a specific part of the body. Selecting acupoints along the meridian is the vital principle for acupressure treatment in depression. The application of specific acupoints related to refreshing the brain and soothing the liver function is the primary procedure across all the studies.

Acupressure also reduced anxiety in participants with psychiatric disorders, sclerosis, uremia, and osteoarthritis in both clinical and community settings. The findings were consistent with a previous systematic review and meta-analysis of acupressure on anxiety by Au et al[16]. However, Hmwe et al[32] suggested inconsis

Ten of the 14 studies reported drop-out rates ranging from 0 to 28.8%, with a mean drop-out rate of 10.2%. Only one study reported the number that dropped out from each group and the reasons for withdrawal[24]. The completion rate was similar to previous studies of acupressure in older people in both clinical and community settings[32]. It was relatively lower than psychological treatment in depression[37]. It should be noted that none of the included studies had long-term follow-up. Furthermore, only one study reported adverse events, including hypotension, dizziness, palpitation, and headache, but without details. Addressing the effects during medium and long-term follow-up periods and the detailed adverse events of acupressure are the priorities suggested for future studies.

Only one study included in our review suggested the potential mechanisms through which the stimulation of particular acupoints on the skin can reduce depression and anxiety by altering the concentration of neurotransmitters, reducing the levels of adrenocorticotrophic hormones and hydroxytryptamine-5 in the brain, resulting in calmness[31]. Previous studies of acupuncture, which shared the same TCM theory with acupressure but used different manipulation technique (acupuncture uses needle), suggested that antidepressant effects of acupuncture are the result of the interaction inbetween multiple targets and levels in neural system. Acupuncture not only improves monoamine neurotransmitters, inhibits the hyperactive HPA axis, but also activates neurotrophic pathways, improves hippocampal neurogenesis, and inhibits inflammatory cytokines[38]. A study of electroacupuncture of acupoints "Baihui" and "Sanyingjiao" in chronically stressed rates significantly increased the activities of 5-HT by increasing the bingding site of 5-HT1A receptors in the hippocampus of depressed rats[39]. A clinical study of acupuncture in women with menopausal depression showed significant increases in serum levels of Norepine

The first systematic review and meta-analysis of acupressure in depression showed a significantly greater overall effect than the controls. However, it is important to be aware of several limitations when interpreting the results.

We excluded 16 Chinese studies that reported poorly, and we were unable to find complete details of study design features relevant to the risk of bias assessment. Thus, trials meeting our inclusion criteria beyond those identified may exist.

Also, only three included trials focused on mild-to-moderate primary depression, and no evidence was found in patients with moderate or severe depression, making generalizability to this patient group difficult.

The included studies differ substantially with regard to participants, treatment frequency and duration, and acupoints selected. Meanwhile, the exact techniques of acupressure and therapeutic composition of acupoints were less undermined and inclusive, making comparisons between these included RCT studies difficult.

No study included in our meta-analysis measured “qi”, which is the primary rationale for the selection of acupoints, and may be a confounding factor for the interpretation of the findings. Even though, we could still perform a meta-analysis and a quantitative synthesis of the included studies.

As a non-invasive, safe and simple technique, acupressure has the potential to be promoted in clinical practice. The present study found that acupressure is feasible to improve depression and anxiety. Integration of this technique in the care of people vulnerable to mental illnesses, such as older people and postnatal women, would promote their emotional well-being and quality of life. That should further reduce the costs and side effects of conventional medication treatment in the standard care system. However, well-designed trials are recommended to provide more solid evidences on the effectiveness of acupressure for mental health promotion.

It is apparent that research in acupressure for mental health is still in its infancy, and further studies of high quality, with large sample sizes and medium- to long-term follow-ups, are warranted to examine the impacts on depression with different severity. Furthermore, effects of different acupoints and pressure retention on depression should be further examined for better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of acupressure in depression. Preliminary findings from our review suggested the potential mechanisms of acupressure may be associated with sympathetic and parasympathetic activities and the concentration of neurotransmitters and hormones in the neural networks. Future studies investigating the neurophy

This review found emerging evidence to support certain positive effects of acupre

Originated from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), acupressure is a safe and cost-effective complementary treatment for depression.

An increase body of research has been undertaken to assess effectiveness of acupressure in depression, but the evidence thus far is inconclusive.

Via the systematic review and meta-analysis, we compared clinical data using acupressure and controls with usual care or sham treatment.

The databases PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, Embase, MEDLINE, and China National Knowledge (CNKI) were searched. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) or single-group trials in which acupressure was compared with control methods or baseline in people with depressive symptoms were included. The primary outcomes were the change between pre- and post-treatment in depression measures. Data were synthesized using a random-effects or a fixed-effects model to analyze the impacts of acupressure treatment on depression and anxiety in people with depression.

A total of 14 RCTs (1439 participants) were identified. Analysis of the between-group showed that acupressure was effective in reducing depression (SMD = -0.58, 95%CI: -0.85 to -0.32, P < 0.0001) and anxiety (SMD = -0.67, 95%CI: -0.99 to -0.36, P < 0.0001) in clinical patients with depressive symptoms. The evidence of acupressure for mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms in patients with chronic diseases was significant. The evidence of certainty in moderate-to-severe primary depression was low. No severe adverse events were reported.

This present review indicated acupressure to be safe and exert certain positive effects in people with mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms. Importantly, the findings should be interpreted with caution due to study limitaitons, including heterogeneity of participants, treatment frequency and duration, the selected acupoints, and sample size.

Future research with a well-designed mixed method is required to provide stronger evidence for clinical decisions and recommendations for its application, as well as an in-depth understanding of acupressure mechanisms and symptoms domains in depression.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Integrative and complementary medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Alkhatib AJ, Stoyanov D, Wang W S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789-1858. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Alsalman R, Alansari B. Relationship of suicide ideation with depression and hopelessness. European Psychiatry. 2020;33:S597-S597. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Clarke DM, Currie KC. Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Aust. 2009;190:S54-S60. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Wulsin LR, Vaillant GE, Wells VE. A systematic review of the mortality of depression. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:6-17. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Goldman LS, Nielsen NH, Champion HC. Awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:569-580. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Jorm AF, Medway J, Christensen H, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Rodgers B. Public beliefs about the helpfulness of interventions for depression: effects on actions taken when experiencing anxiety and depression symptoms. Aust Nz J Psychiat. 2000;34:619-626. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Kessler RC, Soukup J, Davis RB, Foster DF, Wilkey SA, Van Rompay MI, Eisenberg DM. The use of complementary and alternative therapies to treat anxiety and depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:289-294. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Maxwell J. The gentle power of acupressure. RN. 1997;60:53-56. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Beal MW. Acupuncture and oriental body work: traditional and modern biomedical concepts in holistic care--conceptual frameworks and biomedical developments. Holist Nurs Pract. 2000;15:78-87. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Robinson N, Lorenc A, Liao X. The evidence for Shiatsu a systematic review of Shiatsu and acupressure. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:88. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Lane JR. The neurochemistry of counterconditioning Acupressure desensitization in psychotherapy. Energy Psychology Theory, Research, Treatment. 2009;1:31-44. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Borimnejad LAN, Seydfatemi N. The effects of acupressure on preoperative anxiety reduction in school aged children. Healthmed. 2012;6:2359-2361. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Yang MH, Lin L-C. Acupressure in the care of the elderly. Hu Li Za Zhi J Nurs. 2007;54:10-11. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Lee EJ, Frazier SK. The efficacy of acupressure for symptom management: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42:589-603. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Au DW, Tsang HW, Ling PP, Leung CH, Ip PK, Cheung WM. Effects of acupressure on anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acupunct Med. 2015;33:353-359. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336-341. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Prady SL, Richmond SJ, Morton VM, Macpherson H. A systematic evaluation of the impact of STRICTA and CONSORT recommendations on quality of reporting for acupuncture trials. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1577. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M; Editorial Board, Cochrane Back Review Group. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1929-1941. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Jackson D, Turner R. Power analysis for random-effects meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2017;8:290-302. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 1988. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Wu HS, Lin LC, Wu SC, Lin JG. The psychologic consequences of chronic dyspnea in chronic pulmonary obstruction disease: the effects of acupressure on depression. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:253-261. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Lanza G, Centonze SS, Destro G, Vella V, Bellomo M, Pennisi M, Bella R, Ciavardelli D. Shiatsu as an adjuvant therapy for depression in patients with Alzheimer's disease: A pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2018;38:74-78. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Molassiotis A, Suen L, Lai C, Chan B, Wat KHY, Tang J, To KL, Leung CO, Lee S, Lee P, Chien WT. The effectiveness of acupressure in the management of depressive symptoms and in improving quality of life in older people living in the community: a randomised sham-controlled trial. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24:1001-1009. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Tseng YT, Chen IH, Lee PH, Lin PC. Effects of auricular acupressure on depression and anxiety in older adult residents of long-term care institutions: A randomized clinical trial. Geriatr Nurs. 2021;42:205-212. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Tang WR, Chen WJ, Yu CT, Chang YC, Chen CM, Wang CH, Yang SH. Effects of acupressure on fatigue of lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: an experimental pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22:581-591. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Bergmann N, Ballegaard S, Bech P, Hjalmarson A, Krogh J, Gyntelberg F, Faber J. The effect of daily self-measurement of pressure pain sensitivity followed by acupressure on depression and quality of life vs treatment as usual in ischemic heart disease: a randomized clinical trial. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97553. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Zick SM, Sen A, Hassett AL, Schrepf A, Wyatt GK, Murphy SL, Arnedt JT, Harris RE. Impact of Self-Acupressure on Co-Occurring Symptoms in Cancer Survivors. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018;2:pky064. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Yu HC, Carol S; Wu B; Cheng YF. Effect of acupressure on postpartum low back pain, salivary cortisol, physical limitations, and depression: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Tradit Chin Med. 2020;40:128-136. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Rahimi H, Mehrpooya N, Vagharseyyedin S, BahramiTaghanaki H. Self-acupressure for multiple sclerosis-related depression and fatigue A feasibility randomized controlled trial. J Adv Med Biomed Res. 2020;28:276-283. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Dehghanmehr S, Sargazi GH, Biabani A, Nooraein S, Allahyari J. Comparing the Effect of Acupressure and Foot Reflexology on Anxiety and Depression in Hemodialysis Patients: A Clinical Trial. Med Sur Nur J. 2020;8. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Hmwe NT, Subramanian P, Tan LP, Chong WK. The effects of acupressure on depression, anxiety and stress in patients with hemodialysis: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:509-518. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Kalani L, Aghababaeian, H, Majidipour, N. , Alasvand M, Bahrami H. The effects of acupressure on severity of depression in hemodialysis patients a randomized controlled Trial. J Advanced Pharmacy Education Research. 2019;9:67-72. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Rani M, Sharma L, Advani U, Kumar S. Acupressure as an Adjunct to Pharmacological Treatment for Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2020;13:129-135. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Honda Y, Tsuda A, Horiuchi S. Four-Week Self-Administered Acupressure Improves Depressive Mood. Psychology. 2012;3:802-804. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Harris ML, Titler MG, Struble LM. Acupuncture and Acupressure for Dementia Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms: A Scoping Review. West J Nurs Res. 2020;42:867-880. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | Smith CA, Armour M, Lee MS, Wang LQ, Hay PJ. Acupuncture for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD004046. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Hu L, Liang J, Jin SY, Han YJ, Lu J, Tu Y. [Progress of researches on mechanisms of acupuncture underlying improvement of depression in the past five years]. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2013;38:253-258. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Kang HT, Wang. CW. Effect of electroacupuncture on 5-HT1A receptor of hippocampus of the rat model with chronic stress depression. Henan Zhongyi Zazhi. 30:38-40. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 40. | Zhou SH, Wu FD. [Therapeutic effect of acupuncture on female's climacteric depression and its effects on DA, NE and 5-HIAA contents]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2007;27:317-321. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. |

Huang XB, Mu N, Mei F.

Therapeutic effect of acupuncture combined with medicine for the aged depression and its effect on the level of serum brain derived neurotrophic factor |

| 42. | Song C, Halbreich U, Han C, Leonard BE, Luo H. Imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, and between Th1 and Th2 cytokines in depressed patients: the effect of electroacupuncture or fluoxetine treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2009;42:182-188. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |