Revised: May 7, 2014

Accepted: June 14, 2014

Published online: June 28, 2014

AIM: To examine variation in risk factors that contributed to dementia among four elderly cohorts by race and gender.

METHODS: We examined 2008 Tennessee Hospital Discharged database for vascular factors that play a role in both stroke and dementia. Risk factors for dementia were examined for black and white patients aged 65+. Four race-gender groups of patients-white males (WM), black males (BM), white females (WF), and black females (BF) were compared for prevalence of dementia and stroke. A logistic model predicting dementia in each group separately used several vascular factors affecting dementia directly or indirectly through stroke.

RESULTS: Three point six percent of patients hospitalized in 2008 had dementia and dementia was higher among females than males (3.9% vs 3.2%, P < 0.001), and higher among blacks than whites (4.2% vs 3.5%, P < 0.000). Further, BF had higher prevalence of dementia than WF (4.2% vs 3.8%, P < 0.001); similarly BM had more dementia than WM (4.1% vs 3.1%, P < 0.001). In logistic regression models, however, different patterns of risk factors were associated with dementia in four groups: among WF and WM, hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and stroke predicted dementia. Among BF and BM, only stroke and diabetes were related to dementia.

CONCLUSION: Aggressive management of risk factors (hypertension and diabetes) may subsequently reduce stroke and dementia hospitalization.

Core tip: Large medicaid in-hospital database that examines the differences in prevalence of dementia amongst blacks and white population and by gender. Clear differences emerge; blacks have greater burden of dementia including both genders. Risk factors leading to dementia differed between groups. White males and females had a higher association with stroke, hypertension, heart failure and diabetes while blocks had stroke and diabetes only as risk factors. This difference allows us to target these 2 groups with aggressive management early on to reduce the risk of dementia. The strength lies in analyzing a very large database to derive these conclusions.

- Citation: Husaini B, Cain V, Novotny M, Samad Z, Levine R, Moonis M. Variation in risk factors of dementia among four elderly patient cohorts. World J Neurol 2014; 4(2): 7-11

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6212/full/v4/i2/7.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5316/wjn.v4.i2.7

Dementia is among the most common neuropsychiatric disorder, which afflicts 5% to 10% of American elderly populations over the age of 65, and it accounts for a third of all psychiatric diagnoses among the elderly[1-4].

Previous studies have reported on the role of cardiovascular (CVD) factors that contribute to dementia and dementia differences by race and gender. Dementia is higher among blacks and females[5-17]. The role of these CVD factors among elderly cohorts by race-gender remains unknown. Since strokes occur more often among older people, older age possibly contributes to both stroke and dementia[10-15]. Further, older age is also reported to be correlated with higher rates of hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), myocardial infarction (MI), stroke recurrence[15], and congestive heart failure (CHF)[16]. The risk of stroke increases with age in the presence of diabetes[10-19].

While age is related to all cardiovascular risk factors, stroke, and dementia, it remains unclear whether these risk factors are related to dementia across four elderly race-sex cohorts either directly or indirectly through stroke. Thus, in this study, we explore two issues: (1) Do rates of dementia and cardiovascular risk factors vary by race-gender cohorts? (2) Do cardiovascular risk factors that may influence dementia (directly or indirectly) vary by race-gender cohorts?

We used Tennessee Hospital Discharge Data files on elderly patients (aged 65+; n = 154945) discharged in 2008. These files are administrative files submitted for reimbursement; they do not provide clinical data but only ICD-9 diagnoses for which a patient was treated. The attending physicians give diagnoses. Since the Tennessee population is largely composed of whites and blacks, we used four race-sex cohorts of dementia patients (n = 5556): White Males (n = 1778), White Females (n = 3069), Black Males (n = 253), and Black Females (n = 456). While the dementia patient’s sample had only 11% black patients, this proportion is a good representation of black population in Tennessee, which is approximately 14%. The number of black males in the dementia group, though small with limitations on generalizability, is based on those who received the dementia diagnosis by the attending physicians. For the diagnosis of dementia, we used ICD-9 codes of 290.00, 290.20, 290.40-290.42, 291.2, 294.10, 294.11, and 294.20. Data on risk factors hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), hyperlipidemia (CHOL), cardiac arrhythmia (CA), stroke, congestive heart failure (CHF), and MI were also extracted for each patient. All discharge diagnoses in our analyses included a combination of both primary and secondary diagnoses. The dementia sample of patients (n = 5556) included whites (89%), blacks (11%), females (63%) and males (37%). The mean age of dementia patients was 82.5 years (SD = 9.1). Black males were younger in age (78.4 years, SD = 8.8) compared to other cohorts (Table 1). Finally, age-adjusted (per age 65+) dementia prevalence rate (of 690.6 per 100000 elderly) was developed per CDC methodology[20].

| Variables | White males | White females | All white | Black males | Black female | All black | All dementia age 65+ |

| n = 1778 | n = 3069 | n = 9847 | n = 253 | n = 456 | n = 709 | n = 5556 | |

| Column→ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Mean age (SD) | 80.6 (8.4) | 83.9 (9.0) | 82.7 (9) | 78.4 (8.8) | 82.3 (9.4) | 80.9 (9.4) | 82.5 (9.1) |

| HTN (%) | 81.8 | 83.1 | 82.6 | 85.8 | 91.71 | 89.62 | 83.5 |

| DM (%) | 38.1 | 30.6 | 33.4 | 47.2 | 52.61 | 50.62 | 35.6 |

| Chol (%) | 11.31 | 8.5 | 9.6 | 8.7 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 9.5 |

| CA (%) | 42.41 | 36.3 | 38.61 | 35.6 | 32.5 | 33.6 | 37.9 |

| MI (%) | 7.6 | 5.3 | 6.2 | 7.91 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 6.2 |

| CHF (%) | 36.71 | 32.6 | 34.0 | 32.4 | 36.2 | 34.8 | 34.2 |

| Stroke (%) | 63.1 | 54.9 | 57.9 | 72.71 | 63.4 | 66.71 | 59.0 |

| Dementia (%) | 3.1 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 4.21 | 4.21 | 3.6 |

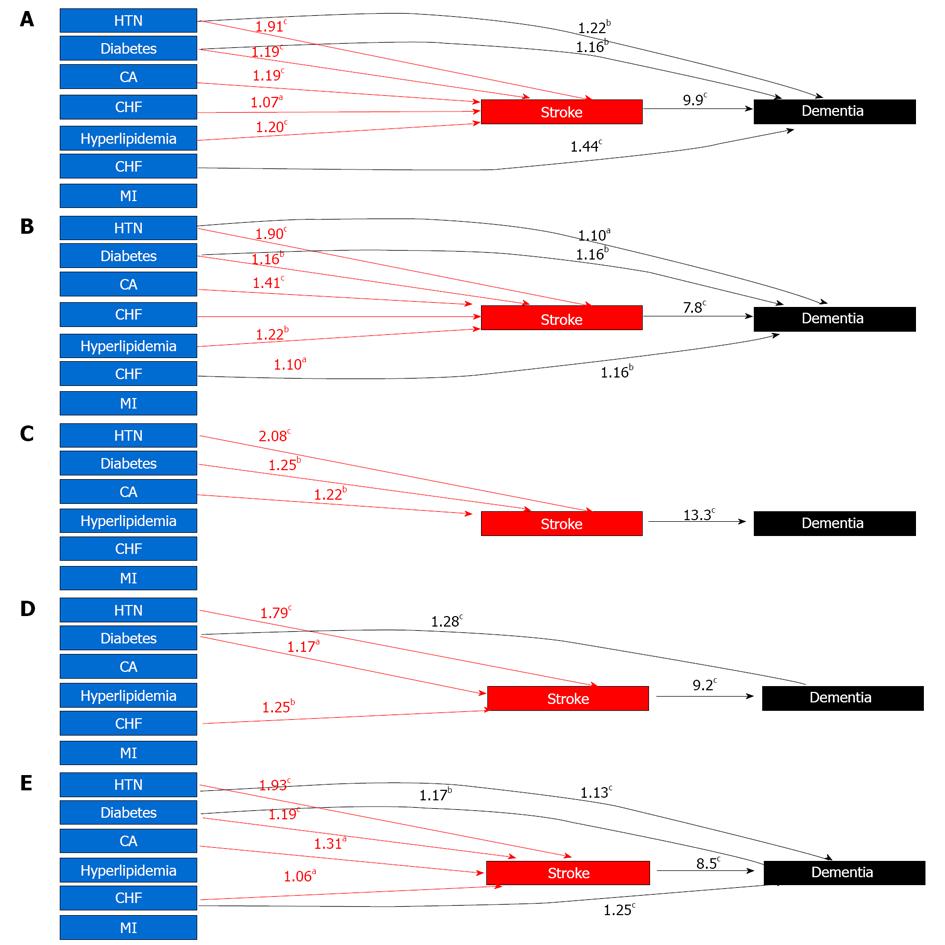

Prevalence of hospitalized dementia patients (per 100000) was directly age-adjusted and indexed to the Year 2000 Census per methodology provided by CDC for the population at risk[20]. Prevalence of dementia risk factors by race and gender were evaluated with Pearson χ2 and the Fisher’s Exact Tests. We also used multivariate logistic regression models to examine both the direct and indirect effects of all risk factors impacting dementia. We used logistic models (controlling age) for each race-gender cohort separately to examine the likelihood of dementia associated with each risk factor (Figure 1). Estimating separate equations for each race-gender cohort allowed for the effects of each risk factor to vary across four cohorts.

Our analyses indicate that both dementia and stroke prevalence increased significantly (P < 0.001) with increasing age: dementia increased from 1.6% among 65-74 years old to 4.2% among 75-84 years old, to 6.6% among elderly aged 85+. Similarly, stroke prevalence increased from 13.1% among 65-74 years old to 17.3% among 75-84 years old, to 18.0% among elderly older than 85 years of age. Further, blacks have higher prevalence of dementia than whites (4.2% vs 3.5%, P < 0.001) and so do females than males (3.9% vs 3.2%, P < 0.001) (not shown). Among four cohorts, dementia prevalence was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in black females (4.2%), compared to black males (4.1%), white females (3.8%) and white males (3.1%). The overall diagnosis of dementia was 3.6% (n = 5556) of all elderly patients hospitalized in 2008 (n = 154945).

As a second trend, while one third of dementia patients had DM, CA, CHF, nearly 60% had stroke and 80% had hypertension (Table 1, col. 7). These risk factors varied across four dementia cohorts in that black patients had higher prevalence of HTN, DM, and Stroke (Table 1, col. 6), whereas white patients had higher prevalence of CA than blacks (Table 1, col. 3). Further, prevalence of MI was higher among males (combined cols. 1 + 4) compared to females (combined cols. 2 + 5). Some of these findings are consistent with those reported previously on risk factors.

Table 2 shows direct effects of CVD factors on dementia as odd ratios for each elderly race-sex cohort. Figure 1A shows both direct effects (in black lines) and indirect effects (in red lines) of risk factors through stroke on dementia.

| Risk factors | White males | White females | All white | Black males | Black females | All black | All dementia patients |

| Column→ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| HTN | 1.222 | 1.101 | 1.152 | 0.72 | 1.04 ns | 0.88 | 1.133 |

| DM | 1.162 | 1.162 | 1.162 | 1.17 ns | 1.283 | 1.243 | 1.172 |

| Chol | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.76 |

| CA | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 1.05 ns | 1.03 ns | 1.04 ns | 0.91 |

| CHF | 1.443 | 1.162 | 1.262 | 1.14 ns | 1.19 ns | 1.17 ns | 1.253 |

| MI | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 1.11 ns | 0.8 | 0.92 | 0.84 |

| Stroke | 9.93 | 7.83 | 8.233 | 13.33 | 9.23 | 10.393 | 8.53 |

The direct effect of risk factors on dementia show that among whites (Table 2, col. 3; Figure 1A and B black lines), four risk factors, namely HTN [odds ratio (OR), 1.15, 95%CI: 1.06-1.25], DM (OR, 1.16, 95%CI: 1.08-1.23), CHF (OR, 1.26, 95%CI: 1.18-1.35); and Stroke (OR, 8.23, 95%CI: 7.7-8.74) predicted onset of dementia. Among black males (Table 2, col. 4; Figure 1C), only stroke (OR, 13.3, 95%CI: 9.92-17.16) predicted dementia; and among black females (Table 2, col. 5; Figure 1D) dementia was predicted by two factors, namely DM (OR, 1.28, 95%CI: 1.04-1.57) and stroke (OR, 9.2, 95%CI: 7.4-11.22).

For indirect effect through stroke (red lines), Figure 1A and 1B show that among white patients (combined males and females), five risk factors (HTN, DM, Hyperlipidemia, CA, and CHF) were all related to stroke which in turn predicted dementia. Among blacks (both males and females in Figure 1C and D), only two factors (HTN, DM) were related to stroke, which in turn predicted dementia. Overall, the indirect effects of HTN, DM, CA and HF on dementia through stroke remain intact for the total sample (Figure 1E).

Our findings indicate that the risk of both stroke and dementia increases with increasing age. For our study, prevalence of dementia among the elderly (aged 65+) was estimated at the rate of 690.6 per 100000 elderly population and this rate per 100000 elderly varied significantly among four cohorts: black males had the highest rate (902.2), followed by black females (811.4), white males (619.9), and white females (617.5). Further, since diabetes almost doubles the risk of dementia[21], and stroke were more prevalent (with increasing age) among blacks, it appears that dementia among blacks, (who survived stroke and thus are in the sample) may largely result from a combination of both diabetes[19,21] and recurring stroke[15].

The influence of stroke on dementia appears to be consistent with previously reported findings of both increasing age, and stroke associated with HTN and DM[15-23]. Since hypertension and diabetes are highly prevalent in all cohorts, additional investigation is needed to examine the role of small versus large vessel strokes in dementia. It is plausible that repeated small vessel infarction among the surviving stroke patients might contribute to the beginning of dementia with large vessel infarcts that may bring dementia to a recognizable level. Further, our data have not supported the previously reported role of hyperlipidemia in elevated levels of dementia. A plausible explanation for the lack of finding regarding hyperlipidemia in our study could be due to an effective treatment of this condition that may have neutralized the effect of hyperlipidemia on dementia.

We recognize that the effect of risk factors on dementia is not as robust as anticipated, particularly among black males. This is possibly due to a small number of black male patients in our sample. We recognize but would remiss, if we do not note that these black males are those who are stroke survivors and thus they show a strong effect of stroke on dementia. It may also be noted that there is a higher mortality among older stroke male patients, and thus fewer number of surviving males, particularly black males in our sample, appears to be consistent with the longevity of black population in Tennessee (72.5 years) where black females live longer (longevity of 76 years) than black males (longevity of 68.7 years). Hence the number of black males in our dementia sample, though small, appears to be consistent with the longevity data for the African American population.

Finally, since DM, and stroke predict dementia across most race-gender cohorts, both primary and secondary preventive measures need to be aggressively pursued since most of these risk factors are amenable to effective management strategies aimed at reducing hospitalization for both stroke and dementia among the elderly.

The authors thank the World Congress of Neurology, Vienna, Austria, September 21-26, 2013

This paper addresses issues of worldwide importance to the field of neurology.

The methods are sound as they utilize administrative files of discharged patients with dementia.

The paper presents extensive, populationbased information regarding patients with a discharge diagnosis of dementia. It presents evidence to show possible variations in risk factors according to gender and race. This information is highly useful for planning public health responses to this important problem.

The paper represents a useful scientific contribution to the neurologic literature.

In this paper, the authors report about the risk factors of dementia among four elderly groups. This is an interesting study. The paper is well written.

P- Reviewers: Louboutin JP, Trkulja V S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, Launer LJ, Laurent S, Lopez OL, Nyenhuis D. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011;42:2672-2713. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2533] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2453] [Article Influence: 188.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Folstein MF, Bassett SS, Anthony JC, Romanoski AJ, Nestadt GR. Dementia: case ascertainment in a community survey. J Gerontol. 1991;46:M132-M138. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 97] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Husaini BA, Sherkat DE, Moonis M, Levine R, Holzer C, Cain VA. Racial differences in the diagnosis of dementia and in its effects on the use and costs of health care services. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:92-96. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kerola T, Kettunen R, Nieminen T. The complex interplay of cardiovascular system and cognition: how to predict dementia in the elderly? Int J Cardiol. 2011;150:123-129. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Baker FM. Dementing illness in African American populations: Evaluation and management for the primary physician. J Geriatr Psych. 1991;24:73-91. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Etgen T, Sander D, Bickel H, Förstl H. Mild cognitive impairment and dementia: the importance of modifiable risk factors. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:743-750. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kume K, Hanyu H, Sato T, Hirao K, Shimizu S, Kanetaka H, Sakurai H, Iwamoto T. Vascular risk factors are associated with faster decline of Alzheimer disease: a longitudinal SPECT study. J Neurol. 2011;258:1295-1303. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hall KS, Gao S, Baiyewu O, Lane KA, Gurejo O, Shen J, Ogunniyi A, Murrell JR, Unverzagt FW, Dickens J. Prevalence rates for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in African Americans: 1992 versus 2001. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:227-233. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Corrada MM, Brookmeyer R, Berlau D, Paganini-Hill A, Kawas CH. Prevalence of dementia after age 90: results from the 90+ study. Neurology. 2008;71:337-343. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 159] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Arntzen KA, Schirmer H, Wilsgaard T, Mathiesen EB. Impact of cardiovascular risk factors on cognitive function: the Tromsø study. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:737-743. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rastas S, Pirttilä T, Mattila K, Verkkoniemi A, Juva K, Niinistö L, Länsimies E, Sulkava R. Vascular risk factors and dementia in the general population aged & gt; 85 years: prospective population-based study. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1-7. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ligthart SA, Moll van Charante EP, Van Gool WA, Richard E. Treatment of cardiovascular risk factors to prevent cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010;6:775-785. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Savva GM, Stephan BC. Epidemiological studies of the effect of stroke on incident dementia: a systematic review. Stroke. 2010;41:e41-e46. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 198] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Whisnant JP. Modeling of risk factors for ischemic stroke. The Willis Lecture. Stroke. 1997;28:1840-1844. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 93] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sheinart KF, Tuhrim S, Horowitz DR, Weinberger J, Goldman M, Godbold JH. Stroke recurrence is more frequent in Blacks and Hispanics. Neuroepidemiology. 1998;17:188-198. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Husaini BA, Mensah GA, Sawyer D, Cain VA, Samad Z, Hull PC, Levine RS, Sampson UK. Race, sex, and age differences in heart failure-related hospitalizations in a southern state: implications for prevention. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:161-169. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Flicker L. Cardiovascular risk factors, cerebrovascular disease burden, and healthy brain aging. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26:17-27. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Piguet O, Garner B. Vascular pharmacotherapy and dementia. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2010;8:44-50. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Khoury JC, Kleindorfer D, Alwell K, Moomaw CJ, Woo D, Adeoye O, Flaherty ML, Khatri P, Ferioli S, Broderick JP. Diabetes mellitus: a risk factor for ischemic stroke in a large biracial population. Stroke. 2013;44:1500-1504. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 108] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. Healthy People 2010 Stat Notes. 2001;1-10. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Ott A, Stolk RP, van Harskamp F, Pols HA, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 1999;53:1937-1942. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Artero S, Ancelin ML, Portet F, Dupuy A, Berr C, Dartigues JF, Tzourio C, Rouaud O, Poncet M, Pasquier F. Risk profiles for mild cognitive impairment and progression to dementia are gender specific. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:979-984. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 189] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Husaini B, Levine R, Sharp L, Cain V, Novotny M, Hull P, Orum G, Samad Z, Sampson U, Moonis M. Depression increases stroke hospitalization cost: an analysis of 17,010 stroke patients in 2008 by race and gender. Stroke Res Treat. 2013;2013:846732. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |