Published online Nov 27, 2017. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v9.i11.224

Peer-review started: August 7, 2017

First decision: September 7, 2017

Revised: September 24, 2017

Accepted: October 16, 2017

Article in press: October 17, 2017

Published online: November 27, 2017

To determine the application of clinical practice guidelines for the current management of diverticulitis and colorectal surgeon specialist consensus in Australia and New Zealand.

A survey was distributed to 205 colorectal surgeons in Australia and New Zealand, using 22 hypothetical clinical scenarios.

The response rate was 102 (50%). For 19 guideline-based scenarios, only 11 (58%) reached consensus (defined as > 70% majority opinion) and agreed with guidelines; while 3 (16%) reached consensus and did not agree with guidelines. The remaining 5 (26%) scenarios showed community equipoise (defined as less than/equal to 70% majority opinion). These included diagnostic imaging where CT scan was contraindicated, management options in the failure of conservative therapy for complicated diverticulitis, surgical management of Hinchey grade 3, proximal extent of resection in sigmoid diverticulitis and use of oral mechanical bowel preparation and antibiotics for an elective colectomy. The consensus areas not agreeing with guidelines were management of simple diverticulitis, management following the failure of conservative therapy in uncomplicated diverticulitis and follow-up after an episode of complicated diverticulitis. Fifty-percent of rural/regional based surgeons would perform an urgent sigmoid colectomy in failed conservative therapy of diverticulitis compared to only 8% of surgeons city-based (Fisher’s exact test P = 0.016). In right-sided complicated diverticulitis, a greater number of those in practice for more than ten years would perform an ileocecal resection and ileocolic anastomosis (79% vs 41%, P < 0.0001).

While there are areas of consensus in diverticulitis management, there are areas of community equipoise for future research, potentially in the form of RCTs.

Core tip: This study illustrates colorectal surgeon specialist consensus with clinical practice guidelines for diverticulitis. While consensus occurred with the majority of guideline recommendations, areas with lack of consensus and even consensus that disagrees with guidelines focuses where future research efforts should be placed.

- Citation: Siddiqui J, Zahid A, Hong J, Young CJ. Colorectal surgeon consensus with diverticulitis clinical practice guidelines. World J Gastrointest Surg 2017; 9(11): 224-232

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v9/i11/224.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v9.i11.224

Sigmoid diverticulitis is a common affliction of the Western world, and recently, due to migration, there has been an increase in the incidence of right-sided diverticulitis[1]. Diverticulitis can be divided into the simple and complicated disease. Complicated disease includes perforation, obstruction, abscesses, fistula and stricture formation. With greater understanding of the pathophysiology of diverticulitis and the advancement of technology, the management of diverticulitis has been evolving in recent times. There is a greater push towards the outpatient management of simple diverticulitis and less aggressive initial management for complicated cases. There is also a change in surgical management options including laparoscopic vs open approach and primary anastomosis vs Hartmann’s procedure for Hinchey Grades 3 and 4. An attempt has been made by several societies to condense some of this into guidelines and practice parameters based on level of evidence[2-4].

Previous surveys[5-9] have assessed correlation in their community with these guidelines. However, no surveys have been conducted in Australasia that evaluates correlation with guidelines for both the current medical and surgical management of diverticulitis, as well as giving consideration to right-sided diverticulitis.

The aim of our survey was to assess consensus of current colorectal specialist practice within Australia and New Zealand with the clinical practice guidelines for the management of simple and complicated diverticulitis (mainly practice parameters published by the Standards Task Force of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons[2] as there are no Australasian guidelines on this subject). We also aimed to highlight areas of community equipoise, to identify areas that will benefit from future research.

All members of the Colorectal Surgical Society of Australia and New Zealand (CSSANZ) were mailed out an anonymous survey consisting of 22 clinical scenarios with multiple choice options (Appendix 1). One reminder mail was sent out after six weeks to non-respondents. The University of Sydney Human Ethics department granted ethical approval and the CSSANZ approved the distribution of the questionnaires.

Surgeon demographics were collected including age range, gender, years practicing, the location of training and current practice, as well as the presence of interventional radiology and an Acute Surgical Unit (ASU) at the place of practice.

The survey was based on clinical scenarios to evaluate the medical and surgical management of uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis. Nineteen questions were derived from the recently published guidelines[2,4] containing an option of 3 to 4 multiple choices, one of which matched the guideline recommendations. The remaining three scenarios were not directly related to the guidelines but were developed to examine surgeon preferences in additional controversies in diverticulitis management not included in the guidelines. The areas covered included initial diagnostic imaging, diagnostic imaging when CT is contraindicated, management of differing size and location of abscesses, management in a medically complex patient, management upon failure of conservative therapy, follow-up options following simple and complicated diverticulitis, surgical management options for different Hinchey grades, as well as operative considerations and management of right-sided diverticulitis. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade was provided for reference. Completion of the survey by other colorectal specialists in the department tested for accuracy and validity before dissemination to other members of CSSANZ.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22. Demographics were tabulated and descriptive statistics (proportion and mean ± SD) were calculated. Two groups were formed - the first compared those that agreed with guideline recommended options and the second compared those that chose the most popular option among the choices provided (i.e., the greatest number of respondents choosing this option). All demographic data were tested for their association with these two groups. Univariate analysis was carried out using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess associations between covariates. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

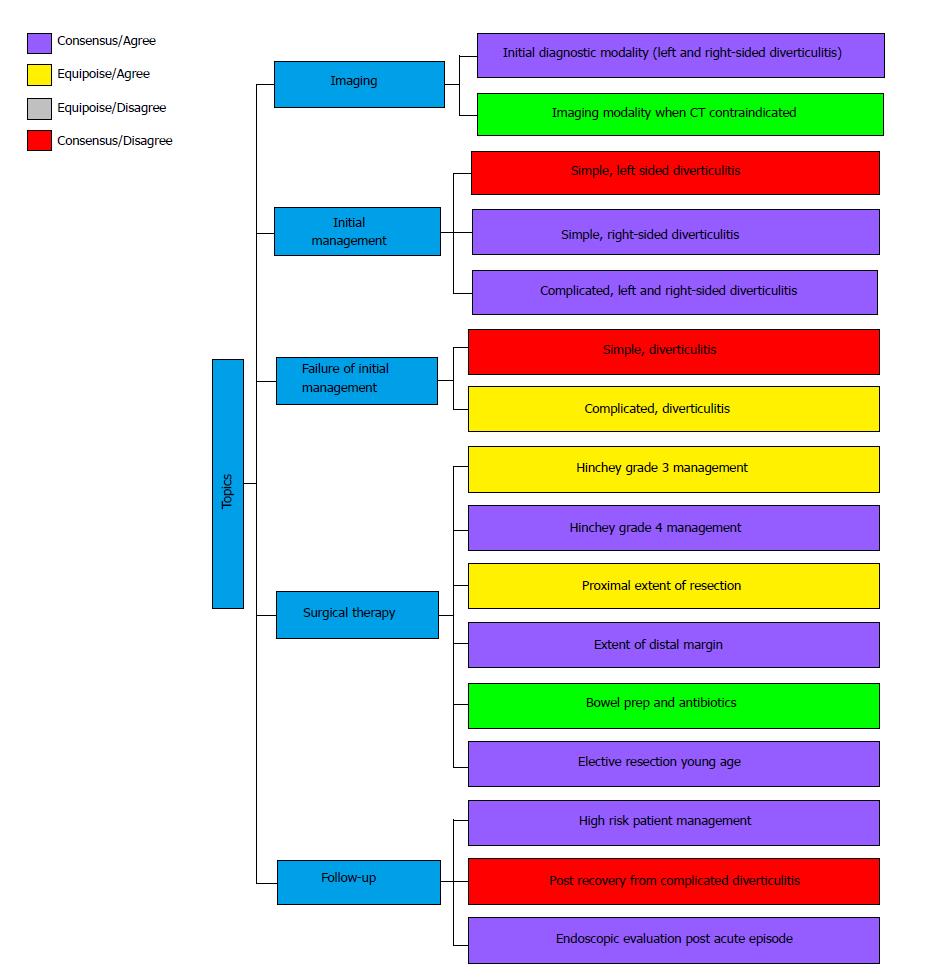

The proportion of surgeons that agreed with the guideline-recommended option for each scenario was calculated, as well as the proportion forming a majority for an option. Evidence suggests[10,11] community equipoise is low when more than 70% of respondents favored one treatment option. Thus, community equipoise was then assessed by classifying the survey scenarios into one of four categories based on the proportion of responses: (1) Consensus/Disagree: scenarios with > 70% of surgeons choosing an option that disagrees with guideline recommendation; (2) Equipoise/Disagree: scenarios with ≤ 70% of surgeons choosing an option that disagrees with guideline recommendation; (3) Equipoise/Agree: scenarios with ≤ 70% of surgeons choosing an option that agrees with guideline recommendation; and (4) Consensus/Agree: scenarios with > 70% surgeons choosing an option that agrees with guideline recommendations.

Of 205 members of the CSSANZ, 102 (50%) responded by returning the survey, of which one was incomplete and excluded from analysis. Surgeon demographics are summarized in Table 1. The mean number of years in practice was 14, with 53% of surgeons aged more than 50 years. Sixty-five percent underwent the majority of their sub-specialty colorectal surgery training in Australia or New Zealand, and 82% are currently practicing in Australia.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| Age range (yr) | |

| 30-39 | 10 (10) |

| 40-49 | 37 (37) |

| 50-59 | 40 (40) |

| Over 60 | 14 (14) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 90 (89) |

| Female | 11 (11) |

| Location of current practice | |

| City (tertiary/quaternary referral center) | 79 (78) |

| City (secondary referral) | 16 (16) |

| Rural | 6 (6) |

| Location of subspecialty training1 | |

| Australia/New Zealand | 66 (65) |

| Europe | 28 (28) |

| North America | 15 (15) |

| Country of current practice | |

| Australia | 84 (83) |

| New Zealand | 17 (17) |

| ASU present in current practice location | 57 (56) |

| Interventional radiology available | 99 (98) |

| Average years in practice (years ± SD) | 14 ± 8.5 |

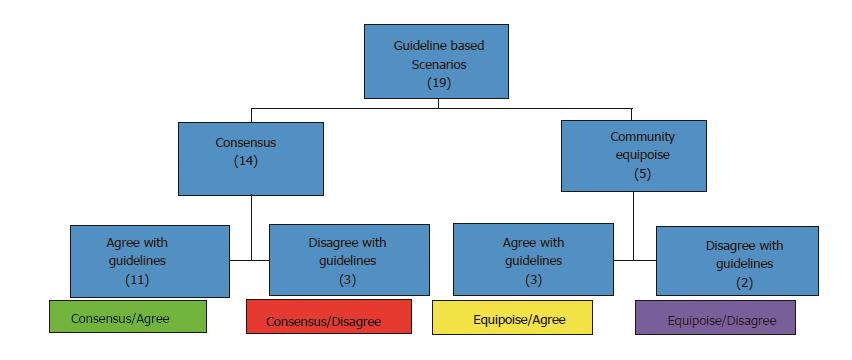

From the 19 guideline based scenarios in the survey, 14 (74%) reached consensus. Of these 14, 3 (21%) scenarios disagreed with guideline recommendation. Five (26%) scenarios showed community equipoise, out of which 2 (40%) disagreed with guideline recommendation and 3 (60%) agreed with guidelines (Figure 1).

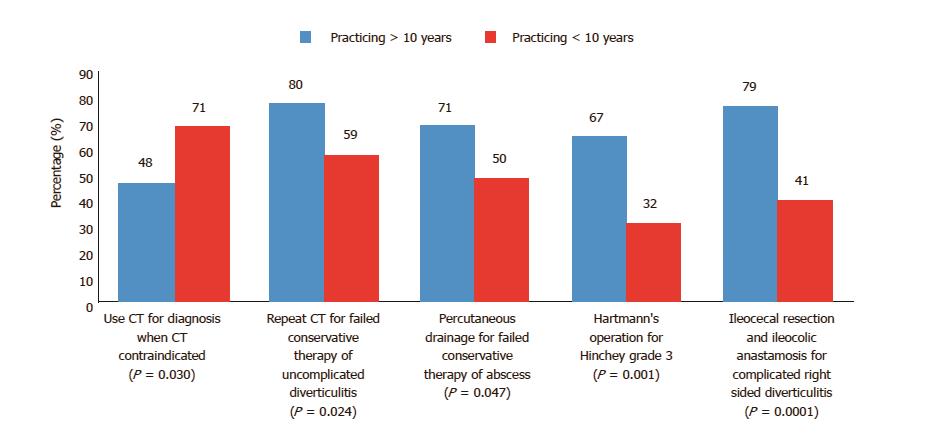

There were three scenarios that reached consensus but disagreed with guideline recommendations. These were: (1) Initial management of diverticulitis: The consensus being admitting for bowel rest and intravenous antibiotics (76%) as opposed to guideline recommendation of outpatient management on oral antibiotics (18%). Four percent would provide supportive care without the use of antibiotics; (2) Failure of conservative management for uncomplicated sigmoid diverticulitis: The consensus being to repeat CT scan of abdomen (71%, shown by multivariate analysis to be more likely if practicing for greater than 10 years - 80% vs 59%, P = 0.043) as opposed to organizing an emergency sigmoid colectomy (11%, more likely if working in a rural/regional center - 50% vs 8%, Fisher’s exact test P = 0.016); and (3) Management following recovery from an episode of complicated diverticulitis: The consensus being no operative management (92%) as opposed to resection (7%).

Equipoise and disagree with guidelines recommendations: There were two scenarios with equipoise and disagreed with guideline recommendation. These were: (1) Imaging modality when CT contraindicated. The majority opinion was to perform a CT scan (57%), with some stating without contrast. Only 21% agreed to the alternative of US or MRI. 71 percent of surgeons practicing less than 10 years vs 48% practicing for more than 10 years would choose CT scan when CT was contraindicated (P = 0.03). Choosing US or MRI was more likely if the surgeon was aged over 50 years old (30% vs 11%, Fisher’s exact test P = 0.017); (2) Use of bowel preparation and antibiotics prior to elective colectomy. The majority (57%) of respondents would use oral, mechanical bowel preparation prior to the procedure and IV antibiotics on induction of general anesthesia. This was more likely to be the case if the surgeon was aged over 50 years old (67% vs 47%, P = 0.04).

Equipoise and agree with guideline recom-mendations: There were three scenarios with equipoise but agreed with guideline recommendations. These were: (1) Failed conservative management for complicated diverticulitis. Sixty-three percent of respondents agreed to image guided percutaneous drainage for a 3 cm mesocolic abscess not responding to conservative management. Univariate analyses demonstrated that a significantly greater number of those practicing in a rural/regional or a secondary referral center compared with those in a tertiary or quaternary referral center (91% vs 56%, P = 0.002), and those practicing for more than 10 years (71% vs 50%, P = 0.047) was associated with this; (2) Hinchey Grade 3 management. Fifty-six percent would do a Hartmann’s procedure as opposed to 3% choosing resection with primary anastomosis and diverting colostomy and 34% choosing on table colonic lavage and colorectal anastomosis with diverting loop ileostomy. A greater proportion of North American sub-specialty trained surgeons (87% vs 51%, Fisher’s exact test P = 0.009) and non-Australasian trained surgeons (77% vs 46%, P = 0.002) would perform a Hartmann’s procedure in this case, as well those practicing for more than 10 years (67% vs 32%, P = 0.001) and surgeons aged over 50 years old (70% vs 40%, P = 0.002); and (3) Proximal extent of resection. The majority (57%) would remove colon where there is thickened, inflamed and hypertrophic tissue and resect the whole sigmoid colon (62% of Australian based vs 35% of New Zealand based surgeons, P = 0.04), whereas 14% would only do the former and 24% would only do the latter.

There were eleven scenarios that reached consensus and agreed with guideline recommendations. These are summarized in Table 2.

| Guideline recommendation | In agreement (%) | P-value |

| CT scan as initial diagnostic modality | 77 | |

| Surgeon North American trained | 100 vs 73 | 0.0151 |

| Surgeon practicing in Australia | 81 vs 59 | 0.047 |

| Right-sided diverticulitis - CT initial imaging | 93 | |

| Surgeon age < 50 years old | 100 vs 89 | 0.021 |

| Right-sided diverticulitis - Initial management oral/IV antibiotics and bowel rest | 95 | |

| Surgeon practicing in Australia | 98 vs 82 | 0.0331 |

| Small diverticular abscess management with antibiotics/bowel rest | 77 | |

| Surgeon North American trained | 100 vs 73 | 0.0151 |

| Large left-sided diverticular abscess management with percutaneous drainage | 81 | |

| Large right-sided diverticular abscess - percutaneous drainage | 83 | |

| Absence of ASU at surgeons place of practice | 93 vs 75 | 0.0161 |

| Hinchey Grade 4 - Hartmann’s procedure | 81 | |

| Surgeon age > 50 years old | 89 vs 72 | 0.034 |

| Routine elective resection in young patient (< 50 years) NOT recommended | 99 | |

| For elective anterior resection - extend distal margin to proximal rectum | 94 | |

| Surgeon Non-European trained | 99 vs 82 | 0.0061 |

| Follow-up for high risk patient with uncomplicated diverticulitis | 99 | |

| Endoscopic evaluation following acute episode | 83 |

The remaining three scenario-based questions that did not relate to guidelines were based on surgical management options. In a patient undergoing resection of the diseased segment in sigmoid diverticulitis, 42% would complete the operation via a colorectal anastomosis with diverting loop ileostomy ± on-table colonic lavage, 31% would complete it with a colorectal anastomosis ± on-table colonic lavage without diversion and 18% with an end colostomy construction. For Hinchey Grade 2, where only surgical management options were provided, 48% would resect with primary anastomosis, 20% chose Hartmann’s operation and 18% chose laparoscopic lavage, with 14% not choosing an option and some stating they would not operate and treat conservatively. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that those practicing in a city setting were more likely to choose resection with primary anastomosis (55% vs 27%, P = 0.035). In a patient with right-sided diverticulitis with confirmed perforation and a 5 cm abscess formation, 66% would perform an ileocecal resection and ileocolic anastomosis. This was more likely if a surgeon was in practice for more than 10 years (78% vs 41%, P < 0.0001) or based in Australia compared to New Zealand (71% vs 41%, P = 0.016). By multivariate analysis, practicing for more than 10 years was found to be significant for performing an ileocecal resection and ileocolic anastomosis (P = 0.001) (Figure 2).

The responses to the 19 guideline-based scenario questions are summarized in Figure 3 according to the sixteen clinically based diverticulitis management topics that they fit into. This is due to the eleven scenarios that reached consensus and agree scenarios in Table 2 being able to coalesce into eight topics.

Our survey is the first to evaluate both medical and surgical management decisions of simple and complicated diverticulitis within Australasia. It shows there remain areas of community equipoise, approximately in a third of the guideline related topics in our survey, and where consensus does exist, it is not always in agreement with accepted guidelines. Some management decisions were found to be dependent on duration of practice.

Individual equipoise measures clinical uncertainty and occurs when an individual clinician is completely undecided. Community equipoise applies when there are differing views among the profession as a whole[10]. There were three topics with moderate quality evidence in guideline recommendations; however, our survey respondents disagreed with these. These were in the areas of management following failed conservative therapy for uncomplicated diverticulitis, recovery from an episode of complicated diverticulitis and use of bowel preparation and antibiotics for elective resection.

The ASCRS practice parameters[2] recommends an urgent sigmoid colectomy for those in whom non-operative management of acute diverticulitis fails. This includes those who have continued abdominal pain or cannot tolerate enteral nutrition secondary to a bowel obstruction or ileus. In our survey, 71% opted for a repeat CT scan instead. This may be a reasonable option in order to exclude possible abscess formation avoiding the need for surgery. The urgency to operate should be assessed on a case by case basis depending on patient factors.

Despite the recommendation of an elective colectomy following recovery from an acute episode of complicated diverticulitis, only 7% of respondents in our survey chose this for an ASA grade 2 patient. The ASCRS[2], The Netherland[12], WGO[4] and German guidelines[13] recommend elective colectomy following recovery from an episode of complicated diverticulitis. However, there is still a need for further research in terms of resection criteria for this group of patients, which may explain why Australasian colorectal specialists are still acting conservatively. In contrast, the Danish guidelines[14] do not recommend elective resection unless it is for patients with fistula or stenosis. Vennix et al[3] concluded in their systematic review of guidelines that surgery is not required in the case of conservatively treated abscess, however, if it is a pelvic abscess then this can be justified. Recently, a population-based analysis[15] also showed a decline in elective colectomy following an episode of diverticulitis. This was most pronounced in those younger than 50 years old (17% to 5%) and with complicated disease states (21% to 8%, P < 0.0001).

The ASCRS practice parameters[2] state that for elective colon resection, oral mechanical bowel preparation is not required; however, oral antibiotics given pre-operatively may reduce surgical site infections. Recently the use of oral, mechanical bowel preparation has been questioned prior to elective colectomy and the ASCRS guidelines recommend the use of oral antibiotics to reduce surgical site infections (SSI). A large systematic review found no statistically significant evidence that patients undergoing colonic surgery benefit from mechanical bowel preparation. Guenaga et al[16] conducted a meta-analysis showing there was no benefit of mechanical bowel preparation in terms of reduced rates of wound infection or anastomotic failure. Bellows’s et al[17] meta-analysis showed that use of oral and IV antibiotics reduced risk of surgical wound infection (RR 0.57, 95%CI: 0.43-0.76, P = 0.0002), but had no effect on organ space infections or risk of anastomotic leak. There is still lack of high-grade research looking specifically at diverticulitis and colonic surgery. Our survey showed that surgeons aged over 50 years old were more likely to use oral, mechanical bowel preparation and IV antibiotics on GA induction compared to those under 50 years.

There were two topics with low quality evidence in guideline recommendations that our survey respondents disagreed with. This included initial management of uncomplicated diverticulitis and initial diagnostic modality when CT contraindicated.

For management of simple, uncomplicated diverticulitis in patients with no systemic manifestations of infection, recent studies[18-21] have pushed towards the outpatient management of simple diverticulitis utilizing oral antibiotics. The recommendation is based on the belief that the body’s host defense mechanisms can manage the inflammation without antibiotics if the patient is otherwise well and immunocompetent. Chabok et al[22] conducted a randomized control trial (RCT) that showed that treatment with antibiotics did not accelerate recovery nor prevent complications or recurrence when compared to treatment without antibiotics. Similar results were reported in a recent Cochrane review of 3 RCTs[23]. Many of the more recent guidelines have moved towards advising outpatient treatment for those with minimal comorbidities and otherwise well. Jackson et al[24] published a systematic review on this showing that 97% of patients were successfully treated in an outpatient type setting. The DIVER trial[25] also demonstrated this, where patients received a dose of IV antibiotics in the emergency department and then were randomized to being hospitalized or discharged for management. The Delphi study[8] demonstrated international acceptance of this as well as other survey studies[5,6]. Contrary to this, the majority (76%) of respondents in our study elected to admit for bowel rest and IV antibiotics. Whether this view may change with a high-quality study being conducted in Australasia needs to be seen.

In keeping with other survey studies[5-8] and with current guidelines[2], the majority (77%) of surgeons opted for CT scan as initial diagnostic modality. However, only 21% would utilize an US or MRI where CT was contraindicated, with some stating they would perform a CT without contrast. This is despite the fact that US has been shown to have a comparable diagnostic accuracy to CT[2,26]. Nevertheless, US does have its limitations and is inferior when considering diagnosis of alternative diseases[27].

Controversy remains regarding the best surgical option for Hinchey Grades 3 and 4 diverticulitis. Like previous surveys[6,8], the majority opted for Hartmann’s procedure for Hinchey Grade 4. However, there remains a divide between Hartmann’s and primary anastomosis with diverting loop ileostomy for Hinchey Grade 3. A systematic review[28] showed that patients undergoing primary anastomosis had lower mortality; however, the studies included were low quality with selection bias. A recent multi-center RCT[29] concluded that primary anastomosis with diverting ileostomy is favored over Hartmann’s procedure. However, a number of limitations were identified following publication. Binda et al[30] brought to attention a number of issues with the trial, including selection bias, surgeons refusing to randomize certain patients, the inclusion of patients with perforation not secondary to diverticulitis and failure to base conclusions on the pre-planned endpoint. The LOLA arm (laparoscopic lavage with sigmoidectomy)[31] of the LADIES trial[32] was prematurely terminated following increased adverse events post laparoscopic lavage compared with sigmoidectomy. However, we still await the results of the DIVA arm comparing Hartmann’s procedure with sigmoidectomy plus primary anastomosis. This will provide randomized, controlled evidence for this controversial issue.

We did not use previous surveys that are already published and then compare our responses to them. This is because previous surveys did not cover as many aspects of diverticulitis management and did not focus as much, if at all, on surgical management. Also, previously published surveys are heterogeneous in terms of areas covered when compared to each other.

Weaknesses in our study include a suboptimal response rate. This may be due in part to the length of the survey, which was necessary to explore the topic. Also, we do not have data on the non-responders and whether they differed markedly from responders. Furthermore, only subspecialty colorectal surgeons were invited to complete this survey in an effort to maximize the response rate. We acknowledge that many general surgeons also treat diverticulitis. These factors limit the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, responses to clinical scenarios may be constrained by the multiple choice options, which may have varied from the respondents’ true preference. Never-the-less, the survey results are still useful in highlighting current practices and areas of equipoise.

In conclusion, this survey has identified areas of community equipoise and areas of clinical practice that disagree with guideline recommendations in the management of diverticulitis. It has also demonstrated that despite the availability of guidelines, some areas in clinical practice reach consensus contrary to these recommendations. In order for guidelines to become more widely acceptable, further higher quality research is necessary in these areas.

Diverticular disease carries a significant disease burden. It ranges from presence of diverticula to simple inflammation to more complex disease processes. There are established guidelines with regards to initial investigations and management options for varying severity of disease. It is unclear whether current clinical practice in Australia and New Zealand is in consensus to established guidelines. The aim of this study was to determine the application of clinical practice guidelines for the current management of diverticulitis and colorectal surgeon specialist consensus in Australia and New Zealand.

There remains disagreement in areas of diverticulitis management including the move to outpatient management and treatment without antibiotics for simple diverticulitis; and operative strategies for Hinchey grade 3 and 4 diverticulitis. This, together with low quality evidence for some guideline recommendations, means that guidelines need to be reviewed and revised with more recent studies.

The achievement of this study is in highlighting areas of equipoise and consensus, albeit not with guideline recommendations, to be areas of future research to provide better quality evidence so that guidelines may be adopted.

Areas of further research identified include initial management of simple diverticulitis, failure of conservative management for diverticulitis, whether recovery following complicated diverticulitis requires operative intervention, use of bowel preparation and proximal extent of resection for elective resection and surgical management of Hinchey Grade 3 diverticulitis. Higher quality evidence to back up recommendations for these will result in better outcomes for patients and given the increasing disease burden, will also help reduce the future financial burden on health care organizations dealing with this.

Evidence suggests community equipoise is low when more than 70% of respondents favor one treatment option. Thus, community equipoise was assessed by classifying the survey scenarios into one of four categories based on the proportion of responses: (1) Consensus/Disagree: scenarios with > 70% of surgeons choosing an option that disagrees with guideline recommendation; (2) Equipoise/Disagree: scenarios with ≤ 70% of surgeons choosing an option that disagrees with guideline recommendation; (3) Equipoise/Agree: scenarios with ≤ 70% of surgeons choosing an option that agrees with guideline recommendation; and (4) Consensus/Agree: scenarios with > 70% surgeons choosing an option that agrees with guideline recommendations.

It is an interesting piece to read and publish. It provides very good overview of Australian surgeons’ opinions on diverticulitis guidelines.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Isik A, Kirshtein B, Lo ZJ, Nah YW, Rubbini M, Wu ZQ, Zhu WM S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhao LM

| 1. | Cristaudo A, Pillay P, Naidu S. Caecal diverticulitis: Presentation and management. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2015;4:72-75. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S, Kaiser A, Boushey R, Buie WD, Rafferty JF. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:284-294. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 356] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Vennix S, Morton DG, Hahnloser D, Lange JF, Bemelman WA; Research Committee of the European Society of Coloproctocology. Systematic review of evidence and consensus on diverticulitis: an analysis of national and international guidelines. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:866-878. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Murphy T, Hunt RH, Fried M, Krabshuis JH. World Gastroenterology Organisation Practice Guidelines (Diverticular Disease, 2007). Available from: http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/UserFiles/file/guidelines/diverticular-disease-english-2007.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Schechter S, Mulvey J, Eisenstat TE. Management of uncomplicated acute diverticulitis: results of a survey. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:470-475; discussion 475-476. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | de Korte N, Klarenbeek BR, Kuyvenhoven JP, Roumen RM, Cuesta MA, Stockmann HB. Management of diverticulitis: results of a survey among gastroenterologists and surgeons. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e411-e417. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Munikrishnan V, Helmy A, Elkhider H, Omer AA. Management of acute diverticulitis in the East Anglian region: results of a United Kingdom regional survey. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1332-1340. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | O’Leary DP, Lynch N, Clancy C, Winter DC, Myers E. International, Expert-Based, Consensus Statement Regarding the Management of Acute Diverticulitis. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:899-904. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jaung R, Robertson J, Rowbotham D, Bissett I. Current management of acute diverticulitis: a survey of Australasian surgeons. N Z Med J. 2016;129:23-29. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Johnson N, Lilford RJ, Brazier W. At what level of collective equipoise does a clinical trial become ethical? J Med Ethics. 1991;17:30-34. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Young J, Harrison J, White G, May J, Solomon M. Developing measures of surgeons’ equipoise to assess the feasibility of randomized controlled trials in vascular surgery. Surgery. 2004;136:1070-1076. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Andeweg CS, Mulder IM, Felt-Bersma RJ, Verbon A, van der Wilt GJ, van Goor H, Lange JF, Stoker J, Boermeester MA, Bleichrodt RP; Netherlands Society of Surgery; Working group from Netherlands Societies of Internal Medicine, Gastroenterologists, Radiology, Health echnology Assessment and Dieticians. Guidelines of diagnostics and treatment of acute left-sided colonic diverticulitis. Dig Surg. 2013;30:278-292. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 125] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kruis W, Germer CT, Leifeld L; German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases and The German Society for General and Visceral Surgery. Diverticular disease: guidelines of the german society for gastroenterology, digestive and metabolic diseases and the german society for general and visceral surgery. Digestion. 2014;90:190-207. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 102] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Andersen JC, Bundgaard L, Elbrønd H, Laurberg S, Walker LR, Støvring J; Danish Surgical Society. Danish national guidelines for treatment of diverticular disease. Dan Med J. 2012;59:C4453. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Li D, Baxter NN, McLeod RS, Moineddin R, Nathens AB. The Decline of Elective Colectomy Following Diverticulitis: A Population-Based Analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:332-339. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Güenaga KF, Matos D, Wille-Jørgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD001544. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 192] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bellows CF, Mills KT, Kelly TN, Gagliardi G. Combination of oral non-absorbable and intravenous antibiotics versus intravenous antibiotics alone in the prevention of surgical site infections after colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15:385-395. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 89] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Al-Sahaf O, Al-Azawi D, Fauzi MZ, El-Masry S, Gillen P. Early discharge policy of patients with acute colonic diverticulitis following initial CT scan. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:817-820. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Alonso S, Pera M, Parés D, Pascual M, Gil MJ, Courtier R, Grande L. Outpatient treatment of patients with uncomplicated acute diverticulitis. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:e278-e282. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Etzioni DA, Chiu VY, Cannom RR, Burchette RJ, Haigh PI, Abbas MA. Outpatient treatment of acute diverticulitis: rates and predictors of failure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:861-865. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mizuki A, Nagata H, Tatemichi M, Kaneda S, Tsukada N, Ishii H, Hibi T. The out-patient management of patients with acute mild-to-moderate colonic diverticulitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:889-897. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chabok A, Påhlman L, Hjern F, Haapaniemi S, Smedh K; AVOD Study Group. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:532-539. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 290] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shabanzadeh DM, Wille-Jørgensen P. Antibiotics for uncomplicated diverticulitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD009092. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jackson JD, Hammond T. Systematic review: outpatient management of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:775-781. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Biondo S, Golda T, Kreisler E, Espin E, Vallribera F, Oteiza F, Codina-Cazador A, Pujadas M, Flor B. Outpatient versus hospitalization management for uncomplicated diverticulitis: a prospective, multicenter randomized clinical trial (DIVER Trial). Ann Surg. 2014;259:38-44. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 112] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Laméris W, van Randen A, Bipat S, Bossuyt PM, Boermeester MA, Stoker J. Graded compression ultrasonography and computed tomography in acute colonic diverticulitis: meta-analysis of test accuracy. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2498-2511. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 158] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Flor N, Maconi G, Cornalba G, Pickhardt PJ. The Current Role of Radiologic and Endoscopic Imaging in the Diagnosis and Follow-Up of Colonic Diverticular Disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207:15-24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Constantinides VA, Tekkis PP, Athanasiou T, Aziz O, Purkayastha S, Remzi FH, Fazio VW, Aydin N, Darzi A, Senapati A. Primary resection with anastomosis vs. Hartmann’s procedure in nonelective surgery for acute colonic diverticulitis: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:966-981. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 173] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Oberkofler CE, Rickenbacher A, Raptis DA, Lehmann K, Villiger P, Buchli C, Grieder F, Gelpke H, Decurtins M, Tempia-Caliera AA. A multicenter randomized clinical trial of primary anastomosis or Hartmann’s procedure for perforated left colonic diverticulitis with purulent or fecal peritonitis. Ann Surg. 2012;256:819-826; discussion 826-827. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 259] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Binda GA, Serventi A, Puntoni M, Amato A. Primary anastomosis versus Hartmann’s procedure for perforated diverticulitis with peritonitis: an impracticable trial. Ann Surg. 2015;261:e116-e117. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Vennix S, Musters GD, Mulder IM, Swank HA, Consten EC, Belgers EH, van Geloven AA, Gerhards MF, Govaert MJ, van Grevenstein WM. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage or sigmoidectomy for perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis: a multicentre, parallel-group, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1269-1277. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 165] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Swank HA, Vermeulen J, Lange JF, Mulder IM, van der Hoeven JA, Stassen LP, Crolla RM, Sosef MN, Nienhuijs SW, Bosker RJ, Boom MJ, Kruyt PM, Swank DJ, Steup WH, de Graaf EJ, Weidema WF, Pierik RE, Prins HA, Stockmann HB, Tollenaar RA, van Wagensveld BA, Coene PP, Slooter GD, Consten EC, van Duijn EB, Gerhards MF, Hoofwijk AG, Karsten TM, Neijenhuis PA, Blanken-Peeters CF, Cense HA, Mannaerts GH, Bruin SC, Eijsbouts QA, Wiezer MJ, Hazebroek EJ, van Geloven AA, Maring JK, D’Hoore AJ, Kartheuser A, Remue C, van Grevenstein HM, Konsten JL, van der Peet DL, Govaert MJ, Engel AF, Reitsma JB, Bemelman WA; Dutch Diverticular Disease (3D) Collaborative Study Group. The ladies trial: laparoscopic peritoneal lavage or resection for purulent peritonitis and Hartmann’s procedure or resection with primary anastomosis for purulent or faecal peritonitis in perforated diverticulitis (NTR2037). BMC Surg. 2010;10:29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 93] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |