Published online Apr 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i4.340

Peer-review started: December 28, 2020

First decision: January 18, 2021

Revised: January 18, 2021

Accepted: March 29, 2021

Article in press: March 29, 2021

Published online: April 27, 2021

A complex anal fistula is a challenging disease to manage.

To review the experience and insights gained in treating a large cohort of patients at an exclusive fistula center.

Anal fistulas operated on by a single surgeon over 14 years were analyzed. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging was done in all patients. Four procedures were performed: fistulotomy; two novel sphincter-saving procedures, proximal superficial cauterization of the internal opening and regular emptying and curettage of fistula tracts (PERFACT) and transanal opening of intersph

A total of 1351 anal fistula operations were performed in 1250 patients. The overall fistula healing rate was 19.4% in anal fistula plug (n = 56), 50.3% in PERFACT (n = 175), 86% in TROPIS (n = 408), and 98.6% in fistulotomy (n = 611) patients. Continence did not change significantly after surgery in any group. As per the new algorithm, 1019 patients were operated with either the fistulotomy or TROPIS procedure. The overall success rate was 93.5% in those patients. In a subgroup analysis, the overall healing rate in supralevator, horseshoe, and fistulas with an associated abscess was 82%, 85.8%, and 90.6%, respectively. The 90.6% healing rate in fistulas with an associated abscess was comparable to that of fistulas with no abscess (94.5%, P = 0.057, not significant).

Fistulotomy had a high 98.6% healing rate in simple fistulas without deterioration of continence if the patient selection was done judiciously. The sphincter-sparing procedure, TROPIS, was safe, with a satisfactory 86% healing rate for complex fistulas. This is the largest anal fistula series to date.

Core Tip: This is the largest anal fistula study reported to date, with 1351 procedures performed in 1250 patients over 14 years at an exclusive fistula-care center. A treatment algorithm was consistently followed. Fistulotomy was done for simple fistulas, and a novel sphincter-sparing procedure, transanal opening of intersphincteric space, was performed for complex high fistulas. The overall success rate was 93.5% in all fistulas, 98.6% for simple fistulas, and 86% in complex high fistulas. Fistulas associated with abscesses were managed safely and successfully by definitive surgery on the first attempt . Several novel concepts were developed during the study.

- Citation: Garg P, Kaur B, Goyal A, Yagnik VD, Dawka S, Menon GR. Lessons learned from an audit of 1250 anal fistula patients operated at a single center: A retrospective review. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(4): 340-354

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i4/340.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i4.340

Anal fistula is not the most common anorectal problem but it is undoubtedly among the most dreaded[1] because the two main problems associated with anal fistula management are recurrence and incontinence risk[2]. Therefore, the anal fistula remains an enigma for surgeons even now.

Fistulotomy has been the gold standard procedure for anal fistulas as it is associated with a high success rate, but it cannot be performed in high fistulas because of an increased risk of incontinence[2]. Therefore, the search for a sphincter-saving procedure has been ongoing for several decades[1,3]. Initially, a cutting seton was utilized for high fistulas, as gradual cutting of sphincter muscles was expected to preserve contin

Against this background of paucity of good procedures to treat high complex fistulas, use of an innovative sphincter-saving procedure, proximal cauterization of the internal opening (IO) and curettage of tracts (PERFACT) was initiated by us in 2013[17]. Initially, a success rate of 86% was achieved[17] but it dropped to 50% over time. Therefore, use of another sphincter-saving procedure, transanal opening of intersphincteric space (TROPIS) was begun in 2015[18]. That procedure had a promising short-term success rate of 90% and it was maintained in the long-term[18]. TROPIS has become the standard procedure for high complex fistulas at our center. Fistulotomy is performed for low fistulas. Initially, AFP and then PERFACT procedures were also performed, but are rarely used now because of their low success rates. The experience and the lessons learned by performing these four procedures, fistulotomy, TROPIS, PERFACT, and AFP, in 1250 consecutive anal fistula patients over 14 years at a single specialized anal fistula center are summarized in this review.

The study was conducted at Garg Fistula Research Institute (GFRI), a center that specializes exclusively in anal fistulas,. All consecutive anal fistula patients operated at this center were included in the analysis. All types and grades of anal fistula were included, and all the operations were performed by a single surgeon. Approval was granted by the Indus International Hospital-Institute Ethics Committee and written consent was taken from every patient. The patients were informed about the purpose of the study, and the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

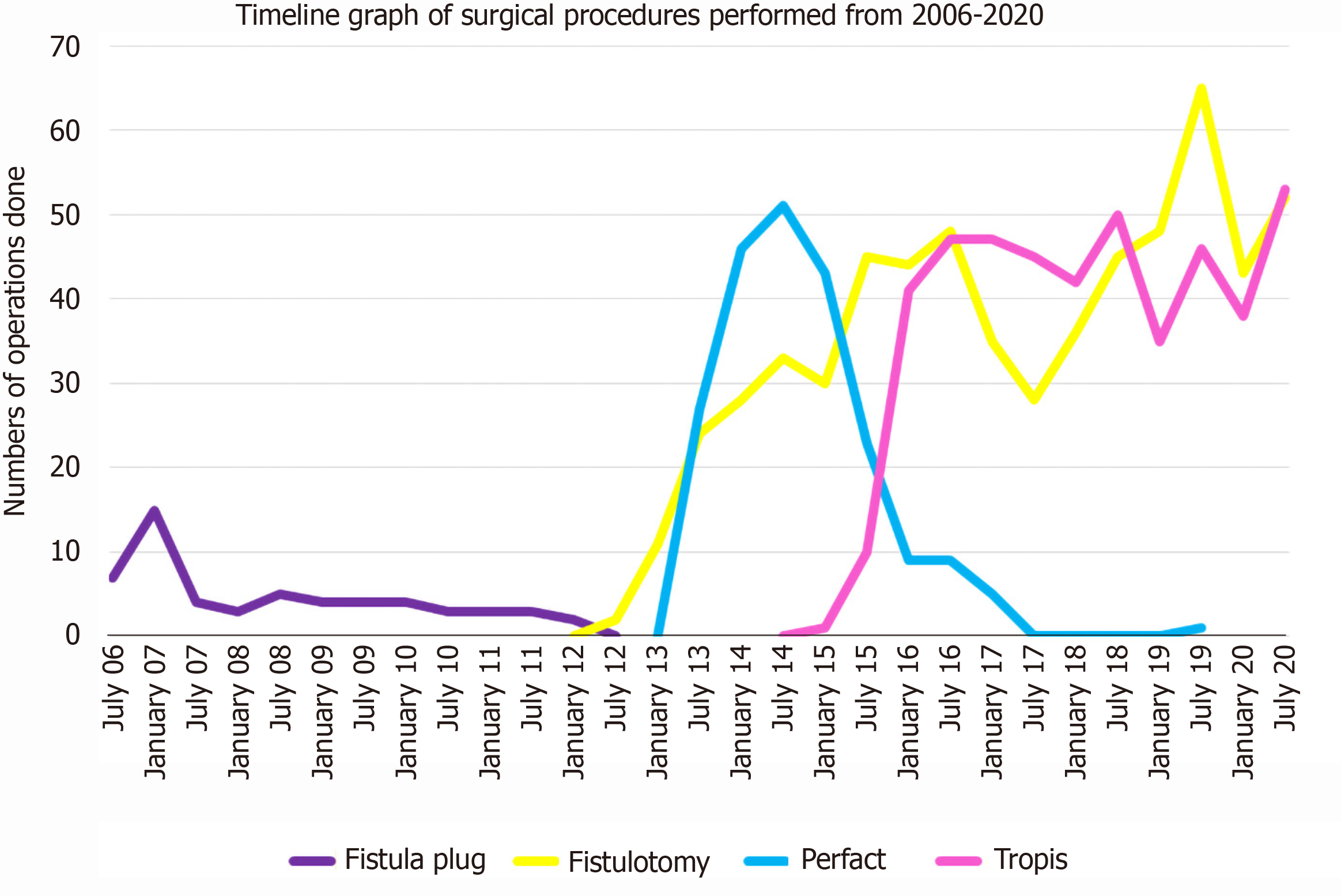

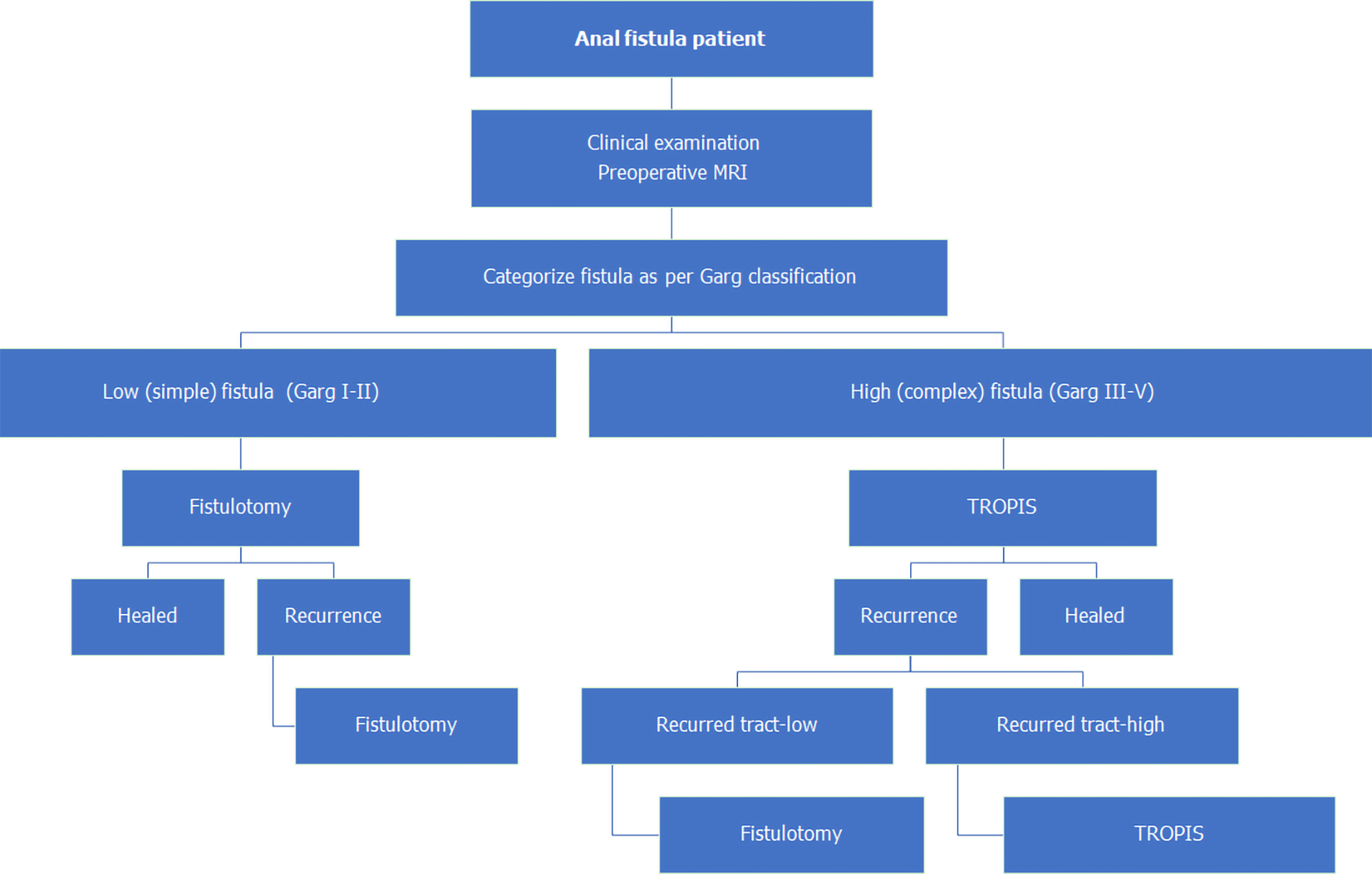

Initially, from September 2006 to November 2012, AFP procedures were done for both low as and high fistulas (Figure 1). As the healing rates with AFP were not satisfactory, it was not performed after November 2012. Since then, from December 2012 to December 2020, fistulotomy has been done for low fistulas. After November 2012, two innovative sphincter-saving procedures were performed for complex high fistulas. The PERFACT procedure was performed for complex fistulas from August 2103 to June 2017 (Figure 1)[17]. However, due to a high recurrence rate, PERFACT procedure was used sparingly after February 2015. The TROPIS procedure was performed in its place for complex fistulas[18] (Figure 1) and its use is ongoing through December 2020[19]. Currently, the GFRI algorithm is to do fistulotomy for low fistulas and TROPIS for complex high fistulas (Figures 1 and 2)[18]. In case of a fistulotomy recurrence, another fistulotomy was done. If a recurrence occurred after a TROPIS procedure, then TROPIS was repeated if a high tract persisted, or a fistulotomy was performed if only a low tract remained (Figure 2). Before 2015, PERFACT was the main procedure done for high fistulas, and in fistulas recurring after a PERFACT procedure, the same procedure was repeated. After 2015, the TROPIS procedure was performed in patients who had a fistula recurrence after a previous PERFACT procedure because the TROPIS success rate was much higher than the PERFACT rate.

Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was done on all patients. Postoperative MRI was not done in all patients but was done in patients who were keen to confirm the fistula's radiological healing. They were usually patients who had been operated on multiple times and were frustrated due to fistula recurrences. Abscesses associated with fistulas were managed definitively at the first operation. No staged procedures (i.e. incision and drainage followed by definitive fistula surgery at a later date) were done. Incontinence was assessed objectively by Vaizey scores[19]. A score of 0 indicated perfect continence; a score of 24 indicated total incontinence[19]. Incontinence was scored before surgery and at long-term follow-up.

A low anal fistulas involved less than one-third of the external anal sphincter. A high anal fistula involved more than one-third of the external anal sphincter. A simple anal fistula was a fistula that could safely be managed by fistulotomy without any risk of continence. A complex anal fistula was a fistula that carried a high risk of incontinence if a fistulotomy was performed. Such fistulas cannot be managed by fistulotomy, and a sphincter-sparing procedure was indicated.

Fistula healing was reported as clinical or radiological. Clinical healing required complete healing of all the fistula tracts, closure of the external opening/openings and cessation of pus from all external openings and the anus for at least 3 mo. Radiological healing required complete healing of the internal opening (IO) and the intersph

AFP is a procedure in which a synthetic plug, an anal fistula plug, was inserted in the fistula tract and the IO was closed over the plug with an absorbable suture.

Fistulotomy is a procedure in which the fistula tract was laid open from the external to the internal opening. The intersphincteric branch, if present, was also laid open in continuity.

In the PERFACT procedure, a small 5-8 mm margin of mucosa around the IO was electrocauterized and the external fistula tracts were thoroughly curetted and cleaned. The external tracts were kept open and empty in the postoperative period by inserting a tube or regular cleaning with cotton mounted on an artery forceps[17]. The principle behind the PERFACT procedure was that in the presence of infection, the IO would heal better by secondary intention (i.e. by creating a raw wound on and around the internal opening) rather than by primary intention (i.e. closure with sutures or staples). The drawback of this procedure was that sepsis/infection in the intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract was not properly managed, which resulted in a high incidence of delayed recurrence.

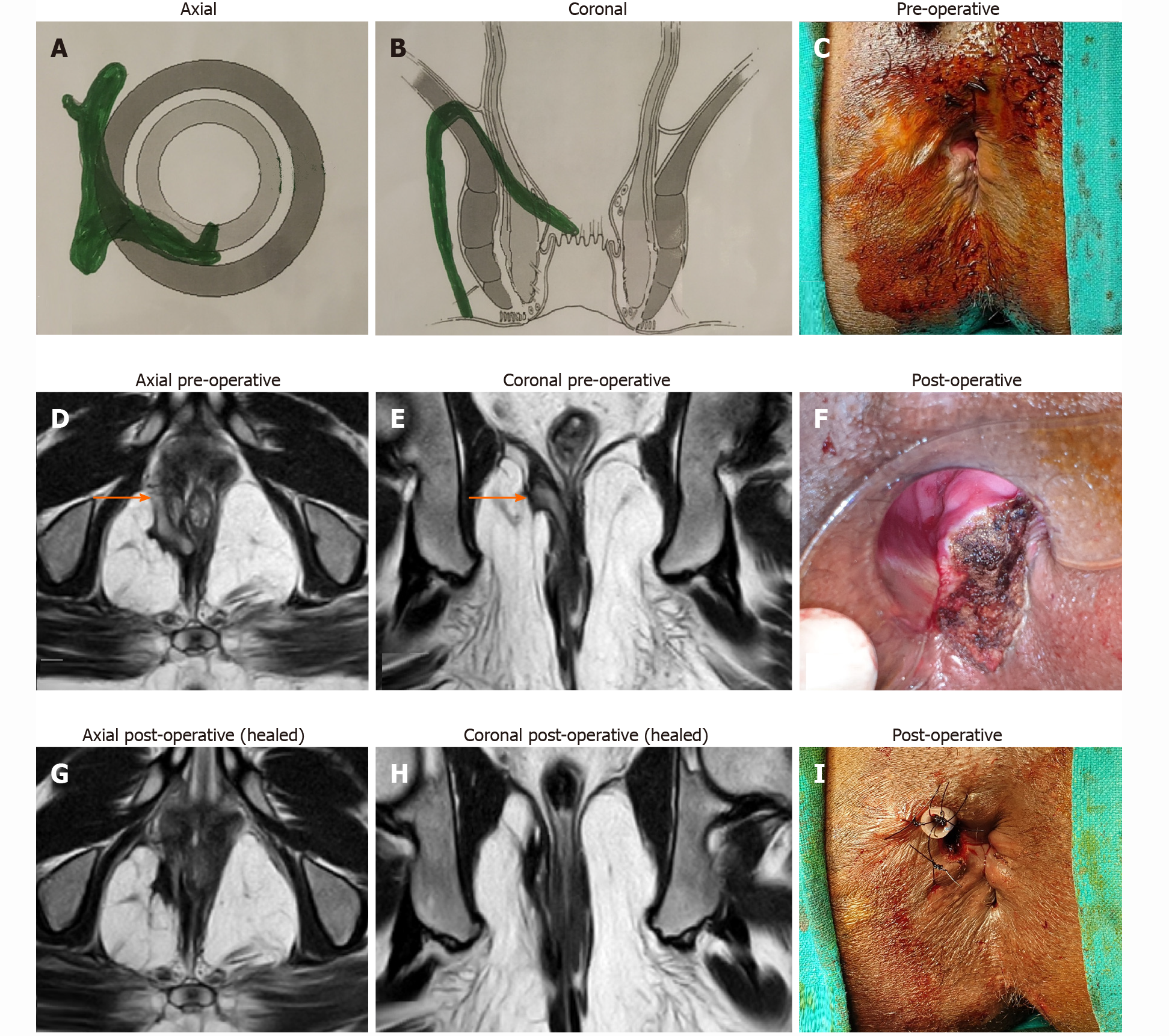

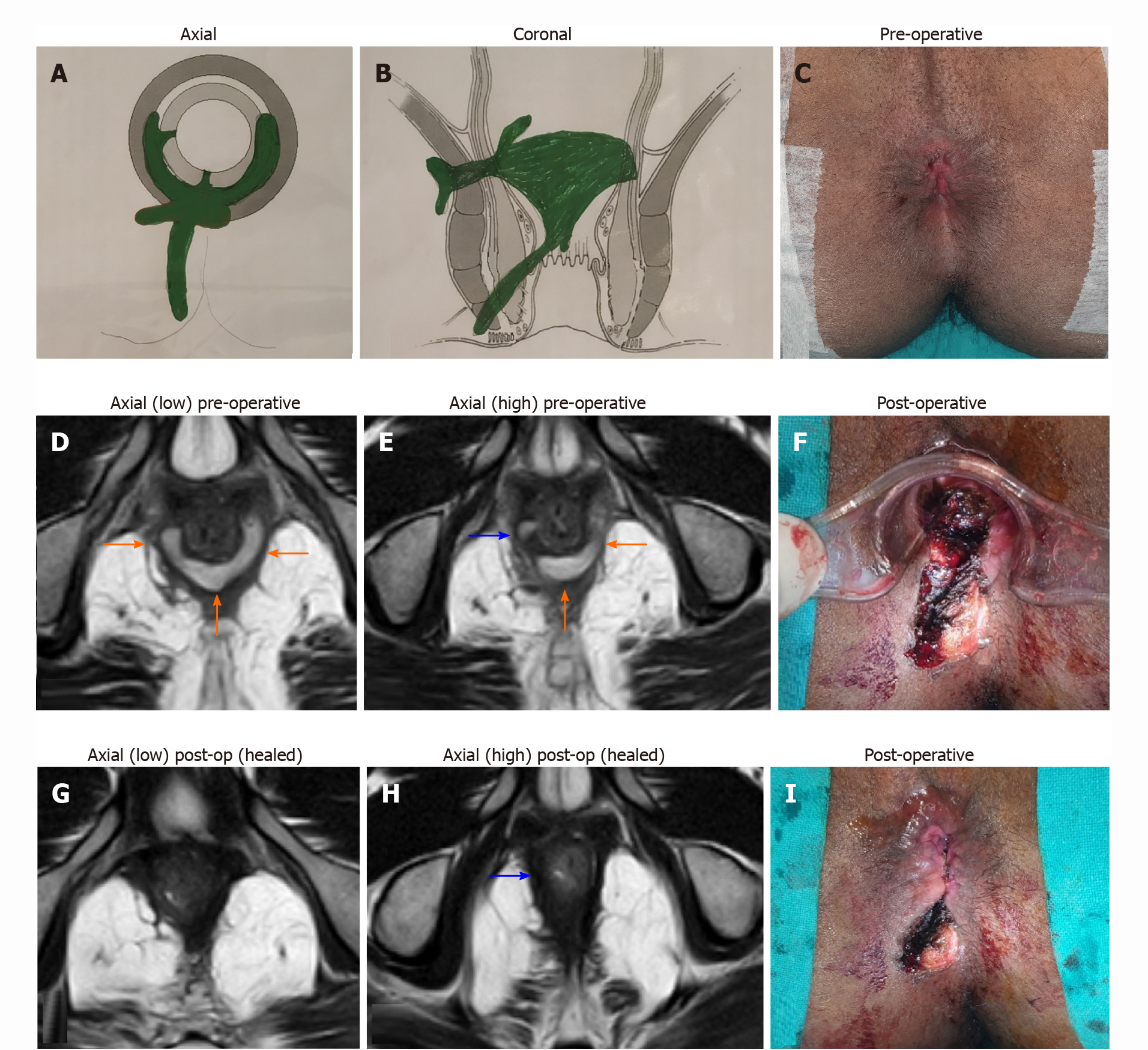

In the TROPIS procedure, the IO along and the intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract were both laid open into the anal canal through the transanal route. The resulting wound, an opened up intersphincteric space, in the anus was left open to heal by secondary intention (Figures 3F and 4F). Thus, both the IO and the intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract healed well by secondary intention despite infection. The external tracts were curetted and cleaned. A tube (abdominal drain kit tube was used in the present study was placed in the cleaned tracts from the external opening up to the lateral border of the external sphincter. The tube was sutured with the perianal skin (Figure 3F). When the wound inside the anus had healed completely, implying healing of the IO and the intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract, then the tube in the external tract was removed. Thus, the tracts on both sides of the external sphincter were managed without cutting or damaging the external sphincter in any way. The tracts inside the external sphincter were managed by the TROPIS procedure and the tracts external to the external sphincter were managed by curettage and insertion of the tube. (Figures 3 and 4).

The patients were meticulously followed-up regularly at the institute until the fistula healed. After that, they were meticulously followed-up by telephone or personal messaging apps. Fistula healing was assessed at 6 mo after surgery and then at long-term follow-up. Any recurrence of symptoms like pain, swelling or pus discharge, was promptly assessed by clinical examination and an MRI.

A total of 1250 patients were operated on, and 1351 surgical procedures were performed over 14 years (Table 1). AFP was done in 56 patients, with a median follow-up of 151 (range, 105-171) mo, fistula healing in 19.4% and recurrence in 80.6%. The PERFACT procedure was performed in 175 patients, with a median follow-up of 78 (range, 13-93) mo, fistula healing in 50.3%, and recurrence in 49.7%. Fistulotomy was done in 611 patients, with a median follow-up 40 (range, 1-105) mo, fistula healing in 98.6% and recurrence in 1.4%. The TROPIS procedure was performed in 408 patients, with a median follow-up of 30 (range, 1-70) mo, healing in 86% and recurrence in 14%. The patient and fistula characteristics are shown in Table 1.

| Fistulotomy | TROPIS | PERFACT | Anal fistula plug | |

| Number of patients (Total = 1250) | 611 | 408 | 175 | 56 |

| Total surgical procedures performed including repeat procedures in a few patients (Total = 1351) | 618 | 456 | 216 | 61 |

| Follow-up, median (Range) | 40 mo (1-105) | 30 mo (1-70) | 78 mo (13-93) | 151 mo (105-171) |

| M/F | 510/101 | 372/36 | 146/29 | 52/4 |

| Age | 37.5 ± 10.7 | 40.5 ± 11.1 | 41.7 ± 12.1 | 49.0 ± 10.9 |

| Fistula type | Simple | High complex | High complex | Simple + complex |

| SJUH classification | I-206, II-143, III-79, IV-179, V-4 | I-1, II-33, III-15, IV-234, V-125 | I-0, II-6, III-43, IV-105, V-21 | Complex-39, Simple-17 |

| GARG classification | I-270, II-327, III-10, IV-0, V-4 | I-1, II-42, III-16, IV-224, V-125 | I-0, II-6, III-44, IV-104, V-21 | |

| Parks | I-349, II-258, III-4, IV-0 | I-34, II-249, III-125, IV-0 | I-6, II-148, III-21, IV-0 | |

| Excluded | 93 (Short FU-30 Lost to FU-63) | 51 (Short FU-38 Lost to FU-13) | 26 (Lost to FU) | 25 (Lost to FU) |

| Healing after first surgery | 97.3% (504/518) | 78.2% (279/357) | 35.6% (53/149) | 19.4% (6/31) |

| Overall healing rate (Median follow-up) | 98.6% (511/518) | 86% (307/357) | 50.3% (75/149) | 19.4% (6/31) |

A total of 1019 fistulas were managed with the GFRI algorithm (Figure 2), all of whom were treated by either fistulotomy or the TROPIS procedure (Table 2). One hundred forty-four patients were excluded. Of those 76 lost to follow-up and 68 had a short follow-up. The median follow-up was 33 (range 1-105) mo. The mean age was 38.7 ± 11.1 yr and the M/F sex ratio was 882/137. The overall healing rate was 93.5% (818/875, Table 2). In a subgroup analysis, the overall healing rate in supralevator was 82.1% (92/112) and 85.8% (151/176) in horseshoe fistula (Table 2). The healing rate in fistulas with an associated abscess was 90.6% (202/233) and was comparable to the healing rate in fistulas with no abscess (94.5%, 616/652, P = 0.057, not significant, Fisher’s exact test) (Table 2).

| Total (n = 1019) | Subgroup analysis | ||||

| Supralevator fistulas (n = 129) | Horseshoe fistula (n = 203) | Associated abscess (n = 258) | No abscess (n = 761) | ||

| Excluded | 144 (Lost to FU-76, Short FU-68) | 17 (Lost to FU-3, Short FU-14) | 27 (Lost to FU-8, Short FU-19) | 35 (Lost to FU-18, Short FU-17) | 109 (Lost to FU-58, Short FU-51) |

| Healing after first surgery | 89.5% (783/875) | 73.2% (82/112) | 76.7% (135/176) | 85.2% (190/223) | 90.9% (593/652) |

| Overall healing rate | 93.5% (818/875) | 82.1% (92/112) | 85.8% (151/176) | 90.6% (202/223) | 94.5% (616/652) |

| P = 0.0578 (not significant) | |||||

Continence did not change significantly after surgery in any of the groups. In the TROPIS procedure group, the preoperative mean incontinence (0.077 ± 0.33) and the postoperative mean incontinence scores (0.112 ± 0.44) were comparable (P = 0.10, not significant, Wilcoxon signed rank test, Table 3). In the fistulotomy procedure group, the difference of the preoperative mean incontinence (0.037 ± 0.47) and postoperative mean incontinence (0.050 ± 0.34) scores was not significant (P = 0.068, Wilcoxon signed rank test, Table 4).

| Preoperative (n = 357) | Postoperative (n = 357) | Significance | |

| Incontinence (number of patients) | Nil = 334, Gas = 16, Liquid = 6, Solid = 1, Urge = 0 | Nil = 328, Gas = 20, Liquid = 6, Solid = 1, Urge = 2 | P = 0.47, Not significant, (Fisher exact test) |

| Vaizey continence scores (mean) | 0.077 ± 0.33 | 0.112 ± 0.44 | P = 0.10, Not significant, (Wilcoxon signed rank test) |

| Preoperative (n = 518) | Postoperative (n = 518) | Significance | |

| Incontinence (number of patients) | Nil = 512, Gas = 3, Liquid = 2, Solid = 1, Urge = 0 | Nil = 504, Gas = 7, Liquid = 4, Solid = 1, Urge = 2 | P = 0.11, Not significant, (Fisher Exact test) |

| Vaizey continence score (mean) | 0.037 ± 0.47 | 0.050 ± 0.34 | P = 0.068, Not significant, (Wilcoxon signed rank test) |

The short-term and long-term success rates of all four procedures are shown and compared in Table 5. For each comparison the short-term cohort is smaller than the long-term cohort. The short-term AFP (median 10 mo) success rate was 71.5%, which dropped to 19.4% at the long-term (median 151) follow-up. Similarly, the short-term (median 9 mo) success rate of the PERFACT procedure was 86.4%[17], which declined to 50.3% on long-term (median, 78 mo) follow-up. The short-term (median: 9 mo) success rate of the TROPIS procedure was 90.4% and the long-term (median: 30 mo) follow-up, the success rate was 86%. In the fistulotomy procedure, the short-term (median: 27 mo) success rate was 100% and the long-term (median: 40 mo) success rate was 98.6%. Because there was a marked decline in the success rates of AFP and PERFACT procedures, both were discontinued. The success rates of fistulotomy and the TROPIS procedures were maintained with time.

| Fistulotomy | TROPIS | PERFACT | Anal fistula plug | |||||

| Short-term (2018)[22] | Long-term follow-up | Short-term (2017)[19] | Long-term follow-up | Short-term (2015)[18] | Long-term follow-up | Short-term (2009)[21] | Long-term follow-up | |

| n | 353 | 611 | 52 | 408 | 44 | 175 | 23 | 56 |

| Follow-up-median (Range) | 27 mo (4-66) | 40 mo (1-105) | 9 mo (6-21) | 30 mo (1-70) | 9 mo (5-14) | 78 mo (42-88) | 10 mo (6-18) | 151 mo (105-171) |

| Overall healing rate | 100% | 98.6% | 90.4% | 86% | 86.4% | 50.3% | 71.4% | 19.4% |

The success rates of the four procedures at 6 mo and at the long-term follow-up were also compared. At 6 mo, the healing rates were 69.4% (34/49) for AFP, 71.4% (120/168) for PERFACT, 78.9% (314/398) for TROPIS, and 97% (583/601) for fistulotomy. The corresponding overall healing rates at the long-term follow-up were 19.4% (6/31) for AFP, 50.3% (75/149) for PERFACT, 86% (307/357) for TROPIS, and 98.6% (511/518) for fistulotomy.

Few complications were reported after these procedures. Bleeding from the postoperative wound occurred in 14/618 (2.3%) after fistulotomy, 12/456 (2.6%) after TROPIS, 2/216 (0.9%) after PERFACT, and none after AFP procedures. The bleeding was controlled with conservative measures (i.e. gentle pressure on the wound for few minutes) in all patients except for one in the fistulotomy and two in the TROPIS group, who required suture ligation of the active bleeder in the operating room. There was no stenosis or stricture formation after the TROPIS procedure, as the mucosal wound involved less than one-third of the anal circumference in all cases. The most frequent complication after AFP was plug extrusion, which occurred in 11/61 (18%) of the AFP procedures. In the 11 patients with plug extrusion, the fistula recurred in six, three were lost to follow-up, and the fistula healed in two.

This study analyzed the operative experience of a single surgeon in performing 1351 anal fistula procedures in 1250 patients. The study has a few strengths. As per our literature search, this is the largest series of anal fistulas published till date . Long-term follow-up of patients was meticulous. The study demonstrated that a dedicated center and a systematic approach (GFRI algorithm, Figure 2) helped achieve satisfactory success rates of 93.5% for all fistulas and 86% for high, complex fistulas.

The series began in 2006, when the AFP procedure was performed for all fistulas, simple as well as complex. The initial results were encouraging (71% healing rate) and prevailed for a few years (Figure 1). However, the healing rate with AFP was not sustained, and by 2012, the use of AFP was discontinued (Figure 1). As an alternative, we started performing fistulotomy for low fistulas. However, the management of high complex fistulas posed a challenge. None of the procedures in vogue had a satisfactory cure rate in high fistulas[15]. Therefore, the use of a novel PERFACT method was contemplated in 2012[17]. The basic principle behind that procedure was that “in the presence of infection, healing by secondary intention is better than by primary intention”[17]. In PERFACT, the IO was not closed by primary intention as was done in AFP, advancement flap, VAAFT, or fibrin-glue procedures. Instead, a raw wound was created all around the IO so that healing could occur by secondary intention[17]. The external tracts were thoroughly curetted and cleaned and were kept clean in the postoperative period. The PERFACT procedure results were encouraging, approaching 86% in high complex fistulas and 80% in supralevator fistulas[17]. However, matters did not proceed as expected.

Although the initial success rate of the PERFACT procedure was satisfactory, after a follow-up of a few years, long-term healing rates started to decrease[17]. The short-term success rate of 80%-86%with the PERFACT procedure declined to 50% with longer follow-up[17,18]. This was surprising because the delayed recurrences were happening even in cases where the IO seemed to have healed well on clinical and MRI exami

The management of an abscess anywhere in the body has two prerequisites, all pus needs to be drained, and the abscess cavity needs to be kept empty by ensuring continuous drainage in the postoperative period[12,20]. That is the reason that simple aspiration of pus from an abscess does not work, and that the abscess cavity has to be deroofed for proper drainage in the postoperative healing period[12,20]. This fundamental principle of abscess management, “draining all pus and ensuring continuous drainage” (DRAPED), needed to be combined with the ISTAC principle to properly manage the intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract[12,20]. As the external anal sphincter is primarily responsible for the control of continence, it needs to be preserved. Deroofing of the intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract could only be done from the transanal route[18,21]. The intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract needed to be opened into the anal canal by incising the mucosa and the internal sphincter through the transanal route. The laid open (deroofed) intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract was left to heal by secondary intention (Figures 3F and 4F)[18,21]. The latter would satisfactorily heal the IO and intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract, which was the principle on which the new TROPIS procedure was based[21].

The major shortcoming of PERFACT and other existing procedures (i.e. inability to tackle the intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract) was overcome in the TROPIS procedure[18,21]. As a result, the success rate of TROPIS has been satisfactory even on long-term follow-up[18]. Although the laying opening of the intersphincteric abscess into the rectum had been advocated several decades earlier[22,23], the routine utilization of this in managing all complex high fistulas was done for the first time at our center[18]. The only other procedures that respect both the ISTAC and DRAPED principles are fistulotomy and FPR[12,16,20,24,25]. Fistulotomy can only be done in low fistulas and is contraindicated in high complex fistulas[12]. In FPR, the complete fistula tract is excised, which is akin to excision of the whole abscess[12,16,20,24,25]. However, FPR is technically demanding, cutting the complete sphincter in suprasphincteric and supralevator fistulas appears too risky, and the prospect of cutting the sphincter, and then repairing it is not acceptable to many patients[12,16]. The LIFT procedure involves ligating the fistula tract in the intersphincteric space. Thus, LIFT takes care of the ISTAC principle but fails to comply with the DRAPED principle, as the abscess (i.e. the intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract) is not adequately and continuously drained in the postoperative period[12,18]. Therefore, the LIFT success rate of up to 42% in complex high fistulas is not very high[15,18,26]. Ironically, the ISTAC principle, based on the significance of managing the sepsis in the intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract, had been ignored for too long. Consequently, the delayed recurrence of fistulas was not explained and fistula management was frustrating and seemed enigmatic[12].

The GFRI algorithm followed since 2015 has been fistulotomy for low fistulas and TROPIS procedures for all high complex fistulas (Figure 2). The GFRI algorithm works well as shown by the results in Table 2. The overall success rate in 1019 patients treated by this algorithm is 93.5% with a median follow-up of 33 (range 1-105) mo. The results are satisfactory considering the large cohort and the long follow-up. Healing rates of 82.1% in supralevator fistulas and 85.8% in horseshoe fistulas are also encouraging. Another critical point demonstrated is that fistulas with associated abscess can be managed successfully and safely by definitive surgery on first presentation rather than by staged procedures, with incision and drainage followed by definitive fistula surgery at a later date (Table 2).

The key determinant of success in fistula surgery is the radiological assessment. The availability of MRI and transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) have greatly enhanced the understanding of anal fistulas[27]. The importance of preoperative assessment of the fistula with MRI or TRUS cannot be overemphasized. A study was done in229 patients from the present cohort in which preoperative clinical assessment by history and physical examination and preoperative MRI assessment were correlated with the intraoperative findings[12]. The results highlighted that one-third (34%) of simple-looking fistulas on clinical assessment were actually complex as predicted by the preoperative MRI and corroborated by the intraoperative findings[12]. The study further demonstrated that more than half (52%) of complex-looking fistulas on clinical assessment were actually found to be even more complex when assessed by the preoperative MRI[12]. They had one or more characteristics, such as an additional fistula tract, an associated abscess, a horseshoe extension, or supralevator, or suprasphincteric tract that was missed by the clinical examination and detected only on MRI. The additional characteristic detected by MRI had the potential to change the surgical decision[12]. Thus, preoperative MRI led to a change in the surgical decision and perhaps helped prevent recurrence in 46% of the patients, 34% of the simple-looking and 52% of the complex-looking fistulas on clinical examination[12]. That study supported our policy of performing preoperative MRI in every patient. Though MRI may seem costly, in the long run it is always cheaper than a recurrence of the fistula, which costs so dearly to the patient financially, physically, and mentally[12]. Another significant advantage of MRI is that it is extremely useful to confirm fistula healing in the postoperative period, which correlates entirely with the long-term healing rates[12].

MRI is immensely beneficial to assess high fistulas, especially supralevator[12] and suprasphincteric fistulas, and fistulas extending into the pelvis[12] (Figures 3 and 4). Accurate fistula assessment by MRI played a pivotal role in achieving high success rates in the management of supralevator and suprasphincteric fistulas in this study[12] (Figure 3 and Table 2). MRI also helped to gain additional insight. Over the last 14 years, after MRI analysis of over 3000 anal fistulas, we did not come across any cases of extrasphincteric fistula. This indicates that extrasphincteric fistulas either do not exist or are extremely rare[12]. The reason could be that extrasphincteric fistulas were described in the era before MRI or TRUS became available and all assessments was based on clinical findings, dye fistulograms, and intraoperative findings[23,28]. Therefore, it is possible that supralevator fistulas with a high rectal opening or high fistulas extending into the levator muscle were erroneously categorized as extrasphincteric fistulas. As most extrasphincteric fistulas were iatrogenic, the second possibility is that this etiology has decreased drastically over time due to a better understanding of anorectal anatomy and availability of advanced radiological techniques[12].

Another strength of MRI is that it can help to accurately classify the fistula, which significantly aids in management (Figure 2). It was observed that the commonly used Parks and St James’s University Hospital (SJUH) grading systems neither stratified fistulas by their severity nor guided in their management[28,29]. For example, a low transsphincteric fistula with two small branches involving just 1 cm of external anal sphincter would be Parks grade II and SJUH grade IV (Table 6). Such SJUH high-grade fistulas can be managed safely with fistulotomy. On the other hand, a high horseshoe intersphincteric fistula would be Parks grade I and SJUH grade II but is a complex fistula that cannot be safely managed by fistulotomy. As neither classification was useful to operating surgeons, a new Garg classification was derived from the experience in the present cohort[12,30] (Table 6).

| Classification | Parks | St James University Hospital | GARG |

| Grade I | Intersphincteric | Intersphincteric- linear | Low fistula- single tract (intersphincteric or transsphincteric) |

| Grade II | Transsphincteric | Intersphincteric-multiple tracts or associated abscess | Low fistula- multiple tracts or associated abscess or horseshoe tract (intersphincteric or transsphincteric) |

| Grade III | Suprasphincteric | Transsphincteric- linear | High fistula-single tract (intersphincteric or transsphincteric) or anterior fistula in a female or associated comorbidities1 |

| Grade IV | Extrasphincteric | Transsphincteric-multiple tract or associated abscess | High fistula- multiple tracts or associated abscess or horseshoe tract (transsphincteric) |

| Grade V | NA | Supralevator or translevator/extrasphincteric | Suprasphincteric or supralevator or extrasphincteric |

The Garg classification categorizes fistulas as low or high depending on the involvement of the external anal sphincter (EAS, Table 6)[12]. Fistulas involving less than one-third of the EAS are classified as low fistulas and those involving more than one-third of the EAS are classified as high fistulas[12]. Grades I and II are low fistulas and grades III-V are high fistulas (Table 6)[12]. The Garg classification classifies fistulas by increasing severity and guides in their management[12,30]. Grades I-II are classified as simple fistulas and are safely amenable to fistulotomy[12,30]. Grades III-V are classified as complex fistulas, for which fistulotomy is contraindicated and a sphincter-sparing procedure is recommended[12,30]. The increased utility of the Garg classification over other classifications was demonstrated in a recent comparative study of 848 patients[12].

Another vital insight gained in this study was regarding the management of fistulas with a non-locatable IO. Studies have shown that inability to accurately locate the IO has been associated with a greater than 50% or up to 20-fold increase in risk of recurrence of fistulas[31]. It has also been shown that of all the risk factors responsible for recurrence, the inability to locate the IO was associated with the highest recurrence risk[32].

The steps followed to locate the IO of the fistula were clinical examination by palpating the area of maximum induration, pulling on the external opening to find the point of dimpling in the anal canal by visual inspection of the anal canal, intraoperative injection of colored solution through the external opening to find its egress from the anus, and a detailed MRI analysis[12]. If all these were not successful in locating IO, the fistula was categorized as IO-non-locatable and was managed with a three-step protocol (known as Garg protocol). First, the MRI was reassessed in detail. Second, in non-horseshoe fistulas, the site of closest contact of the fistula tract to the sphincter complex was identified. The IO was assumed to be located at that site, and the fistula was managed accordingly. Third, in horseshoe fistulas, the IO was assumed to be in the posterior midline for posterior horseshoe and anterior midline for anterior horseshoe fistulas[12]. The outcomes of fistula healing rate and objective incontinence score in IO-non-locatable and IO-locatable groups compared in 700 patients with 564 IO-locatable and 145 IO-non-locatable fistulas. The healing rates were 89% in IO-locatable and 90% in IO non-locatable fistulas (P = 0.55, not significant)[12]. The changes in the objective continence score after surgery were 0.051 ± 0.74 in IO-locatable and 0.090 ± 0.52 inIO non-locatable fistulas (P = 0.28, not significant)[12]. The three-step protocol was quite effective in managing fistulas in which the IO was non-locatable[1].

This study has a few limitations. First, only four different procedures were performed. Of those, TROPIS and PERFACT, were done for the first time in this study. Although the concept of TROPIS, the laying opening of the intersphincteric portion of the fistula tract in the anal canal, has been used in subsequent studies in other centers[33-35], long-term, primarily randomized controlled trials, are needed to corroborate the efficacy of this procedure. Second, although continence was assessed by objective continence scores, anal manometry would have added more value to the study. Apart from high recurrence rate, incontinence is the most challenging issue in the management of high complex anal fistulas. Thorough and accurate assessment of continence before and after fistula surgery is very important for patient satisfaction and objective evaluation of success of any fistula procedure. Therefore, incorporation of anal manometry in the patient evaluation would have strengthened the results.

To conclude, this is the most extensive study of anal fistulas operated by a single surgeon. It shows that a high success rate can be achieved even in complex fistulas by adherence to a systematic algorithm including detailed radiological assessment, accurate fistula classification, and following the ISTAC and DRAPED cardinal principles of fistula management. Even refractory fistulas with a non-locatable IO can be safely and successfully managed by following a simple three-step protocol (Garg protocol). Fistulas with an associated abscess can be managed safely and successfully by definitive fistula surgery on initial presentation. Finally, a dedicated fistula center is optimally focused to gain adequate experience and achieve a high success rate. Therefore, dedicated anal fistula centers are needed in different regions worldwide to serve as referral centers and centers of excellence for teaching. That would go a long way in effectively managing this intractable disease.

Anal fistula is a disease dreaded by both patients and surgeons because the treatment of complex fistulas is very challenging. The two main challenges are high risk of recurrence and damage of the anal sphincters that leads to loss of control over bowel motions (anal incontinence).

An effort was made to manage anal fistulas with a high success rate and minimum loss of continence.

To develop sphincter-sparing procedures to manage high complex anal fistulas. Apart from being sphincter-saving, these procedures should also have high healing rates.

Two innovative sphincter-sparing procedures, transanal opening of intersphincteric space (TROPIS) and proximal superficial cauterization of the IO and emptying regularly of fistula tracts and curettage of tracts (PERFACT) were developed. The results achieved with the use of those two procedures in high complex fistulas were evaluated. The results of fistulotomy in low fistulas AFP procedures performed in early phase of the study were also analyzed.

AFP procedures had very low healing rates (19%); fistulotomy had a very high success rate (98.6%) with minimal loss of incontinence. However, the patient selection had to be done judiciously. Garg classification was extremely helpful in identifying patients suitable for fistulotomy. In high complex fistulas, the PERFACT procedure had a good 86% success rate initially but it declined to 50% during long-term follow-up. The TROPIS procedure had a reasonably high 86% success rate with insignificant risk to continence in high complex fistulas even on long-term follow-up. TROPIS thus became the procedure of choice for high complex fistulas at our center.

Fistulotomy leads to excellent results in low fistulas and TROPIS leads to reasonably high healing rates in high complex fistulas. The risk of continence is minimal if patient selection is done appropriately using the Garg classification.

Future research should focus on improving the TROPIS procedure and developing innovative sphincter-saving procedures that have even better success rates in high complex anal fistulas.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American society of Colon Rectum Surgeons; Society of American Gastrointestinal Surgeons; and Endoscopic and Laparoscopic Surgeons of Asia.

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: lihua Z S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Cooper CR, Keller DS. Perianal Fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63:129-132. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Abramowitz L, Soudan D, Souffran M, Bouchard D, Castinel A, Suduca JM, Staumont G, Devulder F, Pigot F, Ganansia R, Varastet M; Groupe de Recherche en Proctologie de la Société Nationale Française de Colo-Proctologie and the Club de Réflexion des Cabinets et Groupe d'Hépato-Gastroentérologie. The outcome of fistulotomy for anal fistula at 1 year: a prospective multicentre French study. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:279-285. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Aly EH. Is it time to adopt a compulsory sphincter-saving strategy in the treatment algorithm of fistula in ano? Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:1019-1021. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Theerapol A, So BY, Ngoi SS. Routine use of setons for the treatment of anal fistulae. Singapore Med J. 2002;43:305-307. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Hämäläinen KP, Sainio AP. Cutting seton for anal fistulas: high risk of minor control defects. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1443-6; discussion 1447. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | van der Hagen SJ, Baeten CG, Soeters PB, Beets-Tan RG, Russel MG, van Gemert WG. Staged mucosal advancement flap for the treatment of complex anal fistulas: pretreatment with noncutting Setons and in case of recurrent multiple abscesses a diverting stoma. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:513-518. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Meinero P, Mori L. Video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT): a novel sphincter-saving procedure for treating complex anal fistulas. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15:417-422. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Champagne BJ, O'Connor LM, Ferguson M, Orangio GR, Schertzer ME, Armstrong DN. Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of cryptoglandular fistulas: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1817-1821. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Prosst RL, Herold A, Joos AK, Bussen D, Wehrmann M, Gottwald T, Schurr MO. The anal fistula claw: the OTSC clip for anal fistula closure. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1112-1117. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Giamundo P, Geraci M, Tibaldi L, Valente M. Closure of fistula-in-ano with laser--FiLaC™: an effective novel sphincter-saving procedure for complex disease. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:110-115. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Garcia-Arranz M, Garcia-Olmo D, Herreros MD, Gracia-Solana J, Guadalajara H, de la Portilla F, Baixauli J, Garcia-Garcia J, Ramirez JM, Sanchez-Guijo F, Prosper F; FISPAC Collaborative Group. Autologous adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex cryptoglandular perianal fistula: A randomized clinical trial with long-term follow-up. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2020;9:295-301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Garg P, Sodhi SS, Garg N. Management of Complex Cryptoglandular Anal Fistula: Challenges and Solutions. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2020;13:555-567. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Matos D, Lunniss PJ, Phillips RK. Total sphincter conservation in high fistula in ano: results of a new approach. Br J Surg. 1993;80:802-804. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Rojanasakul A. LIFT procedure: a simplified technique for fistula-in-ano. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:237-240. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Jayne DG, Scholefield J, Tolan D, Gray R, Senapati A, Hulme CT, Sutton AJ, Handley K, Hewitt CA, Kaur M, Magill L; FIAT Trial Collaborative Group. A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Safety, Efficacy, and Cost-effectiveness of the Surgisis Anal Fistula Plug Versus Surgeon's Preference for Transsphincteric Fistula-in-Ano: The FIAT Trial. Ann Surg. 2021;273:433-441. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Ratto C, Litta F, Donisi L, Parello A. Fistulotomy or fistulectomy and primary sphincteroplasty for anal fistula (FIPS): a systematic review. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:391-400. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Garg P, Garg M. PERFACT procedure: a new concept to treat highly complex anal fistula. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4020-4029. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Garg P, Kaur B, Menon GR. Transanal opening of the intersphincteric space: a novel sphincter-sparing procedure to treat 325 high complex anal fistulas with long-term follow-up. Colorectal Dis. 2021;. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44:77-80. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Włodarczyk M, Włodarczyk J, Sobolewska-Włodarczyk A, Trzciński R, Dziki Ł, Fichna J. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of cryptoglandular perianal fistula. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:300060520986669. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Li YB, Chen JH, Wang MD, Fu J, Zhou BC, Li DG, Zeng HQ, Pang LM. Transanal Opening of Intersphincteric Space for Fistula-in-Ano. Am Surg. 2021;3134821989048. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Ramanujam PS, Prasad ML, Abcarian H, Tan AB. Perianal abscesses and fistulas. A study of 1023 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:593-597. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Prasad ML, Read DR, Abcarian H. Supralevator abscess: diagnosis and treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:456-461. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Seyfried S, Bussen D, Joos A, Galata C, Weiss C, Herold A. Fistulectomy with primary sphincter reconstruction. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:911-918. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | De Hous N, Van den Broeck T, de Gheldere C. Fistulectomy and primary sphincteroplasty (FIPS) to prevent keyhole deformity in simple anal fistula: a single-center retrospective cohort study. Acta Chir Belg. 2020;1-6. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Jayne DG, Scholefield J, Tolan D, Gray R, Edlin R, Hulme CT, Sutton AJ, Handley K, Hewitt CA, Kaur M, Magill L. Anal fistula plug versus surgeon's preference for surgery for trans-sphincteric anal fistula: the FIAT RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2019;23:1-76. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Vo D, Phan C, Nguyen L, Le H, Nguyen T, Pham H. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the preoperative evaluation of anal fistulas. Sci Rep. 2019;9:17947. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Parks AG, Gordon PH, Hardcastle JD. A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg. 1976;63:1-12. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Morris J, Spencer JA, Ambrose NS. MR imaging classification of perianal fistulas and its implications for patient management. Radiographics. 2000;20:623-35; discussion 635. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Tao Y, Zheng Y, Han JG, Wang ZJ, Cui JJ, Zhao BC, Yang XQ. Long-Term Clinical Results of Use of an Anal Fistula Plug for Treatment of Low Trans-Sphincteric Anal Fistulas. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e928181. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Sygut A, Mik M, Trzcinski R, Dziki A. How the location of the internal opening of anal fistulas affect the treatment results of primary transsphincteric fistulas. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395:1055-1059. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Mei Z, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Liu P, Ge M, Du P, Yang W, He Y. Risk Factors for Recurrence after anal fistula surgery: A meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2019;69:153-164. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Samalavicius NE, Klimasauskiene V, Dulskas A. Intra-anal fistulotomy with marsupialization for recurrent high intersphincteric fistula - a video vignette. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:1450-1451. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Omar W, Alqasaby A, Abdelnaby M, Youssef M, Shalaby M, Anwar Abdel-Razik M, Emile SH. Drainage Seton Versus External Anal Sphincter-Sparing Seton After Rerouting of the Fistula Tract in the Treatment of Complex Anal Fistula: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:980-987. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | El-Said M, Emile S, Shalaby M, Abdel-Razik MA, Elbaz SA, Elshobaky A, Elkaffas H, Khafagy W. Outcome of Modified Park's Technique for Treatment of Complex Anal Fistula. J Surg Res. 2019;235:536-542. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |