Published online Jan 25, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i2.30

Peer-review started: June 29, 2015

First decision: August 16, 2015

Revised: November 26, 2015

Accepted: December 13, 2015

Article in press: December 15, 2015

Published online: January 25, 2016

Processing time: 206 Days and 15.6 Hours

Achalasia is a motility disorder of the esophagus characterized by dysphagia, regurgitation of undigested food, chest pain, weight loss and respiratory symptoms. The most common form of achalasia is the idiopathic one. Diagnosis largely relies upon endoscopy, barium swallow study, and high resolution esophageal manometry (HRM). Barium swallow and manometry after treatment are also good predictors of success of treatment as it is the residue symptomatology. Short term improvement in the symptomatology of achalasia can be achieved with medical therapy with calcium channel blockers or endoscopic botulin toxin injection. Even though few patients can be cured with only one treatment and repeat procedure might be needed, long term relief from dysphagia can be obtained in about 90% of cases with either surgical interventions such as laparoscopic Heller myotomy or with endoscopic techniques such pneumatic dilatation or, more recently, with per-oral endoscopic myotomy. Age, sex, and manometric type by HRM are also predictors of responsiveness to treatment. Older patients, females and type II achalasia are better after treatment compared to younger patients, males and type III achalasia. Self-expandable metallic stents are an alternative in patients non responding to conventional therapies.

Core tip: Achalasia is characterized by dysphagia, regurgitation, chest pain, weight loss and respiratory symptoms. Diagnosis and post-treatment assessment largely rely upon endoscopy, barium swallow study and high resolution esophageal manometry (HRM). Short term improvement in the symptomatology can be achieved with medical therapy or endoscopic botulin toxin injection. Long term relief from dysphagia can be obtained with either laparoscopic Heller myotomy, pneumatic dilatation or per-oral endoscopic myotomy. Age, sex, and manometric subtype by HRM are also predictors of responsiveness to treatment. Self-expandable metallic stents are an alternative in patients non responding to conventional therapies.

- Citation: Esposito D, Maione F, D’Alessandro A, Sarnelli G, De Palma GD. Endoscopic treatment of esophageal achalasia. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(2): 30-39

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i2/30.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i2.30

Achalasia is a motility disorder of the esophagus characterized by dysphagia, regurgitation of undigested food, chest pain, weight loss and respiratory symptoms[1,2].

Achalasia is a relatively rare condition with incidence ranging from 0.3 to 1.63 cases per 100000 people per year in adults[3-6]. There seems to be no difference in sex and racial distribution. Incidence rates of this pathology seems to be rising, it remains unclear if this reflects a true rise in the incidence or an improved diagnosis[3,6,7-16].

Most studies found the median age at the diagnosis to be over 50 years[3,4,17] whereas other authors have suggested a bimodal distribution of incidence by age with peaks around 30 and 60 years of age[7-9].

Although the etiology remains unknown, it has been established that achalasia results from the disappearance of the myenteric neurons leading to loss of peristalsis and failure of relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, particularly during swallowing[18].

Antibodies against myenteric neurons have been found in serum samples obtained from patients affected with achalasia[19-21]. Genetic[22-27], autoimmune[28,29], and viral[30-33] conditions may play a role in the development of the condition.

Since symptoms of achalasia are not specific, the diagnosis of the disease can be delayed for as long as 5 years[34,35]. Dysphagia for solids and liquids occurs in > 90% of patients affected with achalasia, other symptoms include weight loss (35%-91%), food regurgitation (76%-91%), respiratory complications such as chest pain (25%-64%) and heartburn (18%-52%) nocturnal cough (30%) and aspiration (8%)[1,36-38].

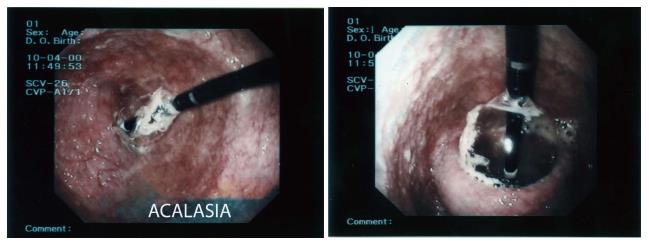

In a patient presenting with dysphagia, it is mandatory to rule out malignancies but also pseudoachalasia or any other anatomical lesions with radiology or endoscopy. Old age, weight loss and rapidly progressing dysphagia are particularly suspected for pseudo-achalasia and thus should be investigated by the mean of and endoscopic ultrasound or computer tomography (CT)-scan[39,40]. These imaging techniques will reveal thickening of the esophageal wall, mass or lesions.

However, both endoscopy and radiology only identify about half of patients with achalasia, especially in early stage. Endoscopy may reveal a dilated esophagus with retained food and a difficult access to gastric cavity due to increased resistance of the gastro-esophageal junction in advanced stages of the disease.

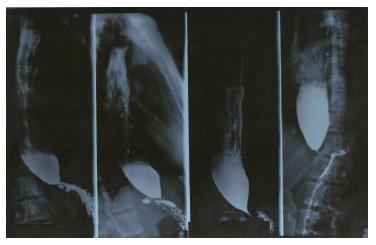

In addition, a timed barium swallow esophagram (TBA) can be done to assess emptying of the esophagus; the height of the barium column 5 min after the ingestion is a measure of emptying[41,42] (Figure 1). A TBA has proven itself useful also in the post-operative assessment of the disease.

Manometry is the mainstay of the assessment in achalasia both before and after treatment. Manometric features of achalasia are absence of peristalsis, incomplete relaxation of LOS on deglutition (residual pressure > 10 mmHg) with increased resting tone of LOS and, sometimes, increased intra-esophageal pressure[2].

High resolution manometry (HRM) is now regarded as the gold standard for the diagnosis of achalasia[43,44], this diagnostic technique is performed by mean of catheters incorporating 36 or more pressure sensors spaced 1 cm apart.

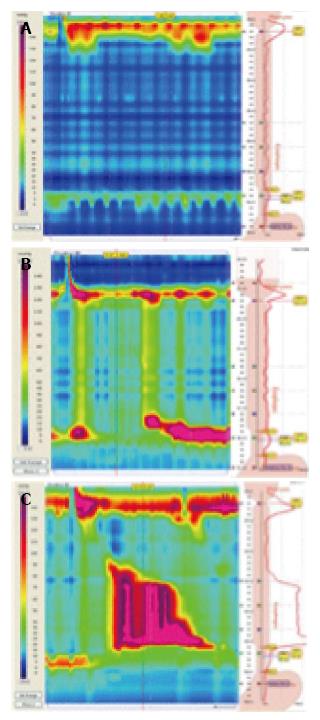

Thanks to the greater accuracy of HRM, three clinically relevant sub-classifications of achalasia have been distinguished on the basis of the pattern of contractility in the esophagus[45].

Type I (classical achalasia; no pressurisation to over 30 mmHg in distal esophagus and failed relaxation on swallow), type II (achalasia with compression or compartmentalisation in the distal esophagus > 30 mmHg), and type III (two or more spastic contractions) (Figure 2).

Since the underlying defect cannot be reversed, the treatment of achalasia remains palliative. Current therapeutic options include pharmacologic therapy, endoscopic treatment and surgery. The primary goal of all therapies is the improvement of the esophageal food passage by reducing the distal esophageal obstruction.

Nitrates and Calcium-channel blockers are the most widely used drugs for the treatment of achalasia[46-49]. Nifedipine is administered 15-60 min before meals in sublingual doses of 10-20 mg. It inhibits the cellular calcium uptake resulting in inhibition of LOS muscle contractions and lowering of the LOS resting pressure by 30%-60%[46-48]. Side effects are seen in up to 30% of patients and include hypotension, headache, and dizziness even if tolerance develops over time.

Only two poorly designed randomized controlled trials have been identified in a Cochrane review by Wen et al[50] about the use of nitrates in achalasia so no solid recommendations can be given at present about this treatment.

Botulin toxin A is a neurotoxin blocking the release of acetylcholine from the synapsis terminals. It can be injected during upper endoscopy through an injection needle directly in four or eight quadrants into the LOS at the dose of 80-100 units[51,52].

This combined endoscopic/pharmacological treatment has proven itself safe and effective. More than 80% of patients have clinical response by one month even if response fades quickly and only about 60% of patients are still in remission at 1-year follow-up[53].

Botulinum toxin compared with pneumodilatation[54-58] and laparoscopic myotomy[59] shows initial comparable relief from dysphagia but a rapid relapse of symptoms after 6-12 mo. So, botulinum toxin, as calcium-channel blockers or nitrates use, should be used as a temporary option before a more durable treatment or in high risk patients who are poor candidates for surgery or pneumodilatation.

Pneumatic dilatation stretches and tears the LOS fibers with air-filled balloons, the most widely used ones are Rigiflex Balloon System (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, United States). The balloons are available in three sizes (30, 35 and 40 mm) made of non-compliant polyethylene; they are placed over a guide-wire at endoscopy, positioned across the LOS and inflated under fluoroscopic guidance, a graded dilation protocol starting with a 30 mm balloon is usually preferred[60] (Figure 3).

An esophageal lavage with large-bore tubes might be needed in patients with mega-esophagus before the procedure. In patients with previous pneumdilatation failure, younger than 40 years or after a previous Heller myotomy it is possible to begin with a 35 mm balloon. The balloon positioning is checked with fluoroscopy or, sometimes, endoscopy; the waist caused by the non relaxing LOS should impinge on the middle portion of the balloon. After careful positioning, the balloon is inflated until the waist is flattened; the pressure needed in the balloon is 7-15 psi of air and is held for 15-60 s.

Patients must be on a liquid diet for several days and fast for 12 h prior to procedure. The procedure is usually performed as an outpatient surgery under conscious sedation in the morning, the patient is then kept under observation for 2-6 h and can return to normal activities the subsequent day. During observation, patients should be assessed for chest pain and fever. A Gastrografin swallowing assessment should be performed in patients complaining with significant pain in order to exclude esophageal perforation.

Subsequent dilatations can be performed after a 2 to 4 wk interval if needed on the basis of symptom relief, LOS pressure measurements or improvement in esophageal emptying[36,61-63].

Pneumatic dilatation with 30, 35 and 40 mm Rigiflex Balloons results in good to excellent symptom relief in 74%, 86% and 90% of patients respectively at 3-year follow-up but nearly two thirds of patients have symptom relapse over a 4-6 years[38,63,64].

Long term relapses can be managed to obtain long-term remission by a repeat dilatation strategy. Best outcomes are seen in patients with type II pattern by HRM, women and in those older than 40 years[1,38,41,65,66].

Patients with type III seem to have better results if treated with Heller myotomy compared to pneumatic dilatation, no significant differences are seen in type I and II. The different response in type III patients seems to be due to the fact that Heller myotomy results in a more extensive and proximal disruption of oesophageal muscle fibers[67].

At present, pneumatic dilatation has proven itself to be the most cost-effective treatment for achalasia over a 5-10 year period[68,69]. Up to one third of patients have complications after pneumatic dilatation, most of them are minor such as bleeding, fever, chest pain, mucosal esophageal hematoma and mucosal tear without perforation. Even though severe gastro-esophageal reflux disease is rare after pneumatic dilatation, 15-35 of patients experiences heartburn which can be treated with proton pump-inhibitors[70]. Perforation is, by far, the most serious complication occurring in about 2.0% of patients[71] (reported rate of 0%-16%), about 50% of perforated patients require surgery thus, poor surgical candidates are poor candidates to pneumatic dilatation as well. In a recent series, 16 consecutive transmural perforations were managed conservatively[72]. Small perforations are usually treated with total parenteral nutrition and antibiotics for days to weeks. Large perforations will require surgical repair by thoracotomy. Difficulty in keeping the balloon in place is a reported risk factor for perforation[73]. Also, performing the initial dilatation with a 35 mm balloon seems to put the patient at risk for perforation, compared to an initial dilatation performed with a 30 mm balloon[66].

Ortega first described a series of 17 patients affected with achalasia and treated with a direct trans-mucosal lower esophageal sphincter myotomy and good clinical, radiologic and manometric results in 1981. No confirmatory work was published, perhaps due to complications such as perforation and mediastinitis[74]. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery made its appearance in 2004 and there has been a tendency towards the development of less invasive alternative to transcutaneous surgical interventions since then. To obtain an access to the mediastinum or the peritoneum, a technique consisting in the creation of a submucosal tunnel closed by a mucosal flap was developed[75].

Per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) was developed from this technique and features the creation of a submucosal tunnel enabling the LES myotomy to be performed away from the mucosal entry site which is closed at the end of the procedure.

In 2007, the first LES myotomy was performed in a porcine survival model[76] and in 2008, Inoue et al[77] used the technique of submucosal tunneling to perform the first endoscopic LES myotomy on humans and coined the term POEM for per oral endoscopic myotomy. Even though, POEM is mainly performed for achalasia, it can be successfully applied in diffuse esophageal spasm, nutcracker and jackhammer esophagus[78,79]. POEM can be also used in patients with prior Heller myotomy and previous endoscopic pneumatic dilatation[80,81].

POEM contraindications include severe pulmonary disease, bleeding disorders esophageal irradiation or esophageal malignancy and endoscopic intervention including endoscopic mucosal resection and[82] endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). POEM requires general anesthesia with the patient in supine position. It is recommended to use anesthesia with positive pressure ventilation to prevent severe mediastinal emphysema[83]. A traditional forward-viewing endoscope and equipment employed in ESD are used. Carbon dioxide is used for insufflation. The esophageal submucosal space is expanded with injection of indigo carmine-saline mixture (typically, 0.3% indigo carmine). The submucosal tunnel is initiated 10-15 cm above the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). The recommended mucosal entry site is, generally, on the anterior wall between 11 and 2 o’clock[83,84]. In case POEM is performed in patients in which a balloon dilatation has been performed with poor results, since the anterior route can be seriously scarred, the incision is usually performed at the 7 o’clock position[85]. After a 2 cm mucosal incision is made, the submucosal tunnel is extended downward by using a technique similar to ESD to reach the gastric cardia 2-3 cm distal to the GEJ.

Accurate identification of EGJ is essential. Delineation of the GEJ is done in a variety of ways like monitoring the endoscope insertion length, identification of the longitudinal palisade vessels in the submucosal layer, change in the submucosal vascular pattern (from palisade to reticular) at EGJ, stenotic segment of the submucosal tunnel, tattooing at the gastric cardia using indocyanine green (ICG) and even transillumination viewed by a second endoscope[86]. The myotomy is performed starting at 2-3 cm distal to the mucosal entry, thus, more than 10 cm above the GEJ and carried up to, at least, 2 cm distally to the GEJ.

At the beginning of the procedure, the circular muscle is dissected and the longitudinal muscle layer is identified; the inter-muscular space is the correct dissection plane. Some authors favor the dissection of the sole circular muscle fiber, since these are regarded as having the major function in muscle contraction and the risk of surrounding structures injury is reduced by keeping the outer muscle intact[87]. The outer longitudinal muscle layer can be extremely thin, the injury to this muscle fibers and the exposure of the mediastinal structures does not cause any sequelae if the mucosa is still intact, thus an inadvertent mucosal flap injury must always be repaired promptly with clip placement, endoscopic suturing or fibrin spray glue[88].

The incision at 2 o’clock position leads to the lesser curvature of the stomach, in contrast, the hiss angle is located at 8 o’clock. Anterior myotomy potentially avoids damage to the sling muscle, and especially His angle so that no anti-reflux procedure is needed. The 2 o’clock approach might be less efficacious at the LES disruption which is the main goal of the achalasia surgery leading to less relieve of dysphagia but may be useful in avoiding symptomatic GERD after the procedure. In contrast, the 5 o’clock position for the myotomy may lead to less dysphagia but could theoretically have more GERD which can be treated with PPI[83].

Using CO2 for insufflation and positive-pressure ventilation prevents severe pneumomediastinum should a perforation occur. The muscle layer cutting is continued for at least 2 cm distal to the GEJ; closure of the mucosal entry site can be performed with either hemostatic clips or endoscopic suturing (OverStitchTM Endoscopic Suturing System; Apollo Endosurgery Austin, Texas), no statistically significant difference in mean closure time, complications or mean cost have been noted[83].

Closure might also be performed with over-the-scope clip and fibrin glue[89,90]. Whatever closure technique is used, Gentamicin infusion within the submucosal tunnel is reported. After the procedure, patients should have a radiographic study (either plain or contrast enhanced chest and abdominal X-ray) to exclude perforations leading to pneumomediastinum or pneumoperitoneum. Antibiotics are usually given during the procedure and for several days after the discharge[83,87].

Some authors perform an EGDS and a timed barium esophagogram (TBE) on the 1st post-operative day to confirm mucosal integrity. If mucosal integrity is confirmed by these studies, the patient may be allowed to drink on day 1, soft diet is started on day 2 and normal diet can be restarted on day 3[87]. Post-operative TBE can also be used to confront the Vaezi score before and after the procedure. Reported results of POEM are excellent with dysphagia efficacy using Eckardt score in > 90% of subjects, no mortality is reported this far[82,91-100]. On the subject of POEM complications, pneumoperitoneum and pneumomediastinum are usually managed with either paracentesis and by inserting a small caliber of intercostal drainage for a couple of days[87].

Acute intraoperative bleeding can be managed, if the bleeding point can be identified, by mean of normal coagulation techniques used in ESD (Coaggrasper, APC, etc.). In case of an unidentified bleeding point, applying pressure with the tip of the endoscope in the submucosal space or from the natural lumen is suggested. A post-operative hematoma may occur; conservative treatment, keeping the patient fasting with intravenous antibiotics is suggested. The hematoma, usually, resolves spontaneously within 1 to 2 wk.

Post-operative hematemesis, melena, hypotension, retrosternal pain may be the hallmark of a delayed bleeding. CT-scan and emergency upper GI endoscopy are mandatory to confirm the diagnosis. The bleeding point is usually located at the edge of the sectioned muscle; in case the bleeding point cannot be identified, placing a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube is an adequate treatment[101].

GERD is the most frequent adverse event after POEM, prevalence varies considerably[82,90-92,95,96,100,101] and can be as high as 40%.

Early reports regarding the use of self-expanding metallic stent (SEMS) in the treatment of achalasia unresponsive to conventional treatments were published in 1998[102]. SEMS permanently disrupt the muscular fibers of the cardia and represents a safe and effective measure for patients not fit for more invasive therapeutic options; Nitinol coil (InStent Inc., Eden, Praire, United States), Ultraflex (Microvasive, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States) or specially designed (Z-stent, Sigma, Huaian, China) stents have been tested, keeping them in place for 3-7 d[103,104] or 30 d[105].

All the trials regarding the use of metal stents in achalasia reported a technical success of 100% and early clinical success of 87%-100%[102,104-107].

Success rates largely depend on the stent diameter, being higher for 30 mm stents compared with either 25 and 20 mm (87% vs 73% vs 43% clinical remission rate respectively)[107].

Complications reported were migration (5.3% to 37.5%) and chest pain (17% to 40%)[102,104-107], one single case series of 4 patients reported the occurrence of dysphagia recurrence secondary to food bolus impaction or inflammatory stricture (100%)[108], one patient died secondary to aorto-enteric fistula. Even complication rate depends on the diameter, the wider the stent, the lower the migration rate (6.6% vs 13.3% vs 26.7%) and the higher the chest pain rate (40% vs 33% vs 17%, respectively)[107]. All the authors concluded that temporary stent placement is an effective treatment for achalasia and could be used for treating carefully selected cases.

About 90% of patients treated for achalasia can return to good quality of life and normal swallowing function[109]. On the other hand, few can be cured with only one treatment, repeat procedure might be needed as many patients relapse over time.

Success rates for Heller myotomy and dilatation defined as relieve from dysphagia or regurgitation are quite similar as shown in a study from the Cleveland Clinic[63]. Moreover, a large retrospective longitudinal study from Canada shows that the cumulative risk for any subsequent treatment (dilatation, myotomy, or oesophagectomy) after 1, 5, and 10 years was slightly higher for pneumatic dilatation compared to HLM (36.8%, 56.2%, and 63.5% after initial pneumatic dilatation vs 16.4%, 30.3%, and 37.5% after initial myotomy (HR 2.37; 95%CI: 1.86-3.02) but this risk difference only occurred when repeat was recorded as an adverse event[110].

Physiological studies can predict long-term success of therapeutic maneuvers. Eckardt et al[61] reported that remission rates at 2-year follow-up largely depended on post-procedural LOS pressure being 100% for LOS pressure less than 10 mmHg, 71% for post-procedural LOS pressure between 10 and 20 mmHg and 23% for pressure over 20 mmHg.

The timed barium oesophagram is also a better predictor of success than LOS pressure is; patients with complete symptom relief and improvement in oesophageal emptying were likely to fare better than those with symptom relief but poor oesophageal emptying (82% vs 10%) at 3-year follow-up as Vaezi et al[41] reported.

Age, sex, and manometric type by HRM are also predictors of responsiveness to treatment. Success rates for pneumatic dilatation are higher for type II achalasia than for type I and type III (96% vs 56% vs 29% respectively) as Pandolfino et al[45] reported. Type III achalasia might be best treated by laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM). It is still unclear whether the fact that a patient had been previously treated endoscopically may hamper the results of a LHM.

Some studies suggest that previous treatments could negatively impact the results of the laparoscopic operation[111-114] whereas other authors reported that only patients who had been previously treated with both botulin toxin injection and pneumatic dilatation had worst results.

With reference to the age factor, patients younger than 40 years need repeat pneumatic dilatations more often than those older than 40 years usually do; also, male respond less well than women do to pneumatic dilatation[1,61,63,66,115]. Similarly, women younger than 35 years do not respond well to pneumatic dilatation[63]. These finding are probably dues to stronger LOS tone in younger patients. Myotomy is, then, the best treatment for adolescents and young adults. Also, pseudoachalasia is best treated by LHM.

Botulinum toxin injection should be considered as a first line therapy for elderly patients or those in which severe comorbidities make them poor surgical candidates since it is safe, effective and might need to be repeated no more than once a year.

The role of POEM as a substitute for myotomy will have to be defined over time with longer follow-up studies, at present, Inoue highlights it’s usefulness as a re-do procedure in case of LHM failure.

Due to the difficulty to resect adhesions in redo surgery and high morbidity of esophagectomy, POEM is a better choice for treatment recurrence achalasia. Also, a POEM can be useful in these cases as it allows to perform another myotomy in a different location from the prior surgery[87].

P- Reviewer: Fuchs HF, Samiullah S S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Vantrappen G, Hellemans J, Deloof W, Valembois P, Vandenbroucke J. Treatment of achalasia with pneumatic dilatations. Gut. 1971;12:268-275. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Richter JE, Boeckxstaens GE. Management of achalasia: surgery or pneumatic dilation. Gut. 2011;60:869-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Farrukh A, DeCaestecker J, Mayberry JF. An epidemiological study of achalasia among the South Asian population of Leicester, 1986-2005. Dysphagia. 2008;23:161-164. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Sadowski DC, Ackah F, Jiang B, Svenson LW. Achalasia: incidence, prevalence and survival. A population-based study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:e256-e261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Birgisson S, Richter JE. Achalasia in Iceland, 1952-2002: an epidemiologic study. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1855-1860. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Gennaro N, Portale G, Gallo C, Rocchietto S, Caruso V, Costantini M, Salvador R, Ruol A, Zaninotto G. Esophageal achalasia in the Veneto region: epidemiology and treatment. Epidemiology and treatment of achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:423-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Howard PJ, Maher L, Pryde A, Cameron EW, Heading RC. Five year prospective study of the incidence, clinical features, and diagnosis of achalasia in Edinburgh. Gut. 1992;33:1011-1015. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Arber N, Grossman A, Lurie B, Hoffman M, Rubinstein A, Lilos P, Rozen P, Gilat T. Epidemiology of achalasia in central Israel. Rarity of esophageal cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1920-1925. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ho KY, Tay HH, Kang JY. A prospective study of the clinical features, manometric findings, incidence and prevalence of achalasia in Singapore. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:791-795. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. Variations in the prevalence of achalasia in Great Britain and Ireland: an epidemiological study based on hospital admissions. Q J Med. 1987;62:67-74. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Mayberry JF, Rhodes J. Achalasia in the city of Cardiff from 1926 to 1977. Digestion. 1980;20:248-252. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. Studies of incidence and prevalence of achalasia in the Nottingham area. Q J Med. 1985;56:451-456. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Earlam RJ, Ellis FH, Nobrega FT. Achalasia of the esophagus in a small urban community. Mayo Clin Proc. 1969;44:478-483. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Galen EA, Switz DM, Zfass AM. Achalasia: incidence and treatment in Virginia. Va Med. 1982;109:183-186. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Mayberry JF, Newcombe RG, Atkinson M. An international study of mortality from achalasia. Hepatogastroenterology. 1988;35:80-82. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Stein CM, Gelfand M, Taylor HG. Achalasia in Zimbabwean blacks. S Afr Med J. 1985;67:261-262. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Enestvedt BK, Williams JL, Sonnenberg A. Epidemiology and practice patterns of achalasia in a large multi-centre database. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1209-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T. Robbins Pathologic basis of disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 1999; 778-779. |

| 19. | Storch WB, Eckardt VF, Wienbeck M, Eberl T, Auer PG, Hecker A, Junginger T, Bosseckert H. Autoantibodies to Auerbach’s plexus in achalasia. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 1995;41:1033-1038. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Moses PL, Ellis LM, Anees MR, Ho W, Rothstein RI, Meddings JB, Sharkey KA, Mawe GM. Antineuronal antibodies in idiopathic achalasia and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 2003;52:629-636. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Ruiz-de-León A, Mendoza J, Sevilla-Mantilla C, Fernández AM, Pérez-de-la-Serna J, Gónzalez VA, Rey E, Figueredo A, Díaz-Rubio M, De-la-Concha EG. Myenteric antiplexus antibodies and class II HLA in achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:15-19. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Storch WB, Eckardt VF, Junginger T. Complement components and terminal complement complex in oesophageal smooth muscle of patients with achalasia. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2002;48:247-252. [PubMed] |

| 23. | De la Concha EG, Fernandez-Arquero M, Mendoza JL, Conejero L, Figueredo MA, Perez de la Serna J, Diaz-Rubio M, Ruiz de Leon A. Contribution of HLA class II genes to susceptibility in achalasia. Tissue Antigens. 1998;52:381-384. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Verne GN, Hahn AB, Pineau BC, Hoffman BJ, Wojciechowski BW, Wu WC. Association of HLA-DR and -DQ alleles with idiopathic achalasia. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:26-31. [PubMed] |

| 25. | de la Concha EG, Fernandez-Arquero M, Conejero L, Lazaro F, Mendoza JL, Sevilla MC, Diaz-Rubio M, Ruiz de Leon A. Presence of a protective allele for achalasia on the central region of the major histocompatibility complex. Tissue Antigens. 2000;56:149-153. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Nuñez C, García-González MA, Santiago JL, Benito MS, Mearín F, de la Concha EG, de la Serna JP, de León AR, Urcelay E, Vigo AG. Association of IL10 promoter polymorphisms with idiopathic achalasia. Hum Immunol. 2011;72:749-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | de León AR, de la Serna JP, Santiago JL, Sevilla C, Fernández-Arquero M, de la Concha EG, Nuñez C, Urcelay E, Vigo AG. Association between idiopathic achalasia and IL23R gene. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:734-738, e218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gockel HR, Schumacher J, Gockel I, Lang H, Haaf T, Nöthen MM. Achalasia: will genetic studies provide insights? Hum Genet. 2010;128:353-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Booy JD, Takata J, Tomlinson G, Urbach DR. The prevalence of autoimmune disease in patients with esophageal achalasia. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:209-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Facco M, Brun P, Baesso I, Costantini M, Rizzetto C, Berto A, Baldan N, Palù G, Semenzato G, Castagliuolo I. T cells in the myenteric plexus of achalasia patients show a skewed TCR repertoire and react to HSV-1 antigens. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1598-1609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Villanacci V, Annese V, Cuttitta A, Fisogni S, Scaramuzzi G, De Santo E, Corazzi N, Bassotti G. An immunohistochemical study of the myenteric plexus in idiopathic achalasia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:407-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Birgisson S, Galinski MS, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, Richter JE. Achalasia is not associated with measles or known herpes and human papilloma viruses. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:300-306. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Niwamoto H, Okamoto E, Fujimoto J, Takeuchi M, Furuyama J, Yamamoto Y. Are human herpes viruses or measles virus associated with esophageal achalasia? Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:859-864. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Eckardt VF. Clinical presentations and complications of achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:281-292, vi. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Eckardt VF, Köhne U, Junginger T, Westermeier T. Risk factors for diagnostic delay in achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:580-585. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Hulselmans M, Vanuytsel T, Degreef T, Sifrim D, Coosemans W, Lerut T, Tack J. Long-term outcome of pneumatic dilation in the treatment of achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:30-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Eckardt VF, Stauf B, Bernhard G. Chest pain in achalasia: patient characteristics and clinical course. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1300-1304. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Fisichella PM, Raz D, Palazzo F, Niponmick I, Patti MG. Clinical, radiological, and manometric profile in 145 patients with untreated achalasia. World J Surg. 2008;32:1974-1979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Tracey JP, Traube M. Difficulties in the diagnosis of pseudoachalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:2014-2018. [PubMed] |

| 40. | de Borst JM, Wagtmans MJ, Fockens P, van Lanschot JJ, West R, Boeckxstaens GE. Pseudoachalasia caused by pancreatic carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:825-828. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Vaezi MF, Baker ME, Achkar E, Richter JE. Timed barium oesophagram: better predictor of long term success after pneumatic dilation in achalasia than symptom assessment. Gut. 2002;50:765-770. [PubMed] |

| 42. | de Oliveira JM, Birgisson S, Doinoff C, Einstein D, Herts B, Davros W, Obuchowski N, Koehler RE, Richter J, Baker ME. Timed barium swallow: a simple technique for evaluating esophageal emptying in patients with achalasia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:473-479. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE, Schwizer W, Smout AJ. Chicago classification criteria of esophageal motility disorders defined in high resolution esophageal pressure topography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24 Suppl 1:57-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 608] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 46.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kahrilas PJ. Esophageal motor disorders in terms of high-resolution esophageal pressure topography: what has changed? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:981-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Pandolfino JE, Kwiatek MA, Nealis T, Bulsiewicz W, Post J, Kahrilas PJ. Achalasia: a new clinically relevant classification by high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1526-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 661] [Cited by in RCA: 551] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Gelfond M, Rozen P, Gilat T. Isosorbide dinitrate and nifedipine treatment of achalasia: a clinical, manometric and radionuclide evaluation. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:963-969. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Bortolotti M, Labò G. Clinical and manometric effects of nifedipine in patients with esophageal achalasia. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:39-44. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Traube M, Dubovik S, Lange RC, McCallum RW. The role of nifedipine therapy in achalasia: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1259-1262. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Triadafilopoulos G, Aaronson M, Sackel S, Burakoff R. Medical treatment of esophageal achalasia. Double-blind crossover study with oral nifedipine, verapamil, and placebo. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:260-267. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Wen ZH, Gardener E, Wang YP. Nitrates for achalasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD002299. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Pasricha PJ, Ravich WJ, Hendrix TR, Sostre S, Jones B, Kalloo AN. Intrasphincteric botulinum toxin for the treatment of achalasia. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:774-778. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Annese V, Bassotti G, Coccia G, Dinelli M, D’Onofrio V, Gatto G, Leandro G, Repici A, Testoni PA, Andriulli A. A multicentre randomised study of intrasphincteric botulinum toxin in patients with oesophageal achalasia. GISMAD Achalasia Study Group. Gut. 2000;46:597-600. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Leyden JE, Moss AC, MacMathuna P. Endoscopic pneumatic dilation versus botulinum toxin injection in the management of primary achalasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD005046. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Muehldorfer SM, Schneider TH, Hochberger J, Martus P, Hahn EG, Ell C. Esophageal achalasia: intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin A versus balloon dilation. Endoscopy. 1999;31:517-521. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Wilcox CM, Schroeder PL, Birgisson S, Slaughter RL, Koehler RE, Baker ME. Botulinum toxin versus pneumatic dilatation in the treatment of achalasia: a randomised trial. Gut. 1999;44:231-239. [PubMed] |

| 56. | Ghoshal UC, Chaudhuri S, Pal BB, Dhar K, Ray G, Banerjee PK. Randomized controlled trial of intrasphincteric botulinum toxin A injection versus balloon dilatation in treatment of achalasia cardia. Dis Esophagus. 2001;14:227-231. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Mikaeli J, Fazel A, Montazeri G, Yaghoobi M, Malekzadeh R. Randomized controlled trial comparing botulinum toxin injection to pneumatic dilatation for the treatment of achalasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1389-1396. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Zhu Q, Liu J, Yang C. Clinical study on combined therapy of botulinum toxin injection and small balloon dilation in patients with esophageal achalasia. Dig Surg. 2009;26:493-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Zaninotto G, Annese V, Costantini M, Del Genio A, Costantino M, Epifani M, Gatto G, D’onofrio V, Benini L, Contini S. Randomized controlled trial of botulinum toxin versus laparoscopic heller myotomy for esophageal achalasia. Ann Surg. 2004;239:364-370. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Kadakia SC, Wong RK. Graded pneumatic dilation using Rigiflex achalasia dilators in patients with primary esophageal achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:34-38. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Eckardt VF, Aignherr C, Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1732-1738. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Rohof WO, Lei A, Boeckxstaens GE. Esophageal stasis on a timed barium esophagogram predicts recurrent symptoms in patients with long-standing achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:49-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Vela MF, Richter JE, Khandwala F, Blackstone EH, Wachsberger D, Baker ME, Rice TW. The long-term efficacy of pneumatic dilatation and Heller myotomy for the treatment of achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:580-587. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Zerbib F, Thétiot V, Richy F, Benajah DA, Message L, Lamouliatte H. Repeated pneumatic dilations as long-term maintenance therapy for esophageal achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:692-697. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Rohof WO, Salvador R, Annese V, Bruley des Varannes S, Chaussade S, Costantini M, Elizalde JI, Gaudric M, Smout AJ, Tack J. Outcomes of treatment for achalasia depend on manometric subtype. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:718-725; quiz e13-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Boeckxstaens GE, Annese V, des Varannes SB, Chaussade S, Costantini M, Cuttitta A, Elizalde JI, Fumagalli U, Gaudric M, Rohof WO. Pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy for idiopathic achalasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1807-1816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 698] [Cited by in RCA: 579] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Salvador R, Costantini M, Zaninotto G, Morbin T, Rizzetto C, Zanatta L, Ceolin M, Finotti E, Nicoletti L, Da Dalt G. The preoperative manometric pattern predicts the outcome of surgical treatment for esophageal achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1635-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | O’Connor JB, Singer ME, Imperiale TF, Vaezi MF, Richter JE. The cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1516-1525. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Karanicolas PJ, Smith SE, Inculet RI, Malthaner RA, Reynolds RP, Goeree R, Gafni A. The cost of laparoscopic myotomy versus pneumatic dilatation for esophageal achalasia. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1198-1206. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Richter JE. Update on the management of achalasia: balloons, surgery and drugs. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;2:435-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Katzka DA, Castell DO. Review article: an analysis of the efficacy, perforation rates and methods used in pneumatic dilation for achalasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:832-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Vanuytsel T, Lerut T, Coosemans W, Vanbeckevoort D, Blondeau K, Boeckxstaens G, Tack J. Conservative management of esophageal perforations during pneumatic dilation for idiopathic esophageal achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:142-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Metman EH, Lagasse JP, d’Alteroche L, Picon L, Scotto B, Barbieux JP. Risk factors for immediate complications after progressive pneumatic dilation for achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1179-1185. [PubMed] |

| 74. | Ortega JA, Madureri V, Perez L. Endoscopic myotomy in the treatment of achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 1980;26:8-10. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Sumiyama K, Tajiri H, Gostout CJ. Submucosal endoscopy with mucosal flap safety valve (SEMF) technique: a safe access method into the peritoneal cavity and mediastinum. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2008;17:365-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Pasricha PJ, Hawari R, Ahmed I, Chen J, Cotton PB, Hawes RH, Kalloo AN, Kantsevoy SV, Gostout CJ. Submucosal endoscopic esophageal myotomy: a novel experimental approach for the treatment of achalasia. Endoscopy. 2007;39:761-764. [PubMed] |

| 77. | Inoue H, Minami H, Satodate H, Kudo SE. First Clinical Experience of Submucosal Endoscopic esophageal myotomy for esophageal achalasia with no skin incision. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:AB122. |

| 78. | Minami H, Isomoto H, Yamaguchi N, Ohnita K, Takeshima F, Inoue H, Nakao K. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for diffuse esophageal spasm. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E79-E81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Kandulski A, Fuchs KH, Weigt J, Malfertheiner P. Jackhammer esophagus: high-resolution manometry and therapeutic approach using peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM). Dis Esophagus. 2014;Jan 27; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Zhou PH, Li QL, Yao LQ, Xu MD, Chen WF, Cai MY, Hu JW, Li L, Zhang YQ, Zhong YS. Peroral endoscopic remyotomy for failed Heller myotomy: a prospective single-center study. Endoscopy. 2013;45:161-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Sharata A, Kurian AA, Dunst CM, Bhayani NH, Reavis KM, Swanström LL. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) is safe and effective in the setting of prior endoscopic intervention. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1188-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Stavropoulos SN, Modayil RJ, Friedel D, Savides T. The Inter- 25 national Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy Survey (IPOEMS): a snapshot of the global POEM experience. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3322-3338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Friedel D, Modayil R, Stavropoulos SN. Per-oral endoscopic myotomy: major advance in achalasia treatment and in endoscopic surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17746-17755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 84. | Inoue H, Minami H, Kobayashi Y, Sato Y, Kaga M, Suzuki M, Satodate H, Odaka N, Itoh H, Kudo S. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia. Endoscopy. 2010;42:265-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1168] [Cited by in RCA: 1228] [Article Influence: 81.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 85. | Minami H, Inoue H, Haji A, Isomoto H, Urabe S, Hashiguchi K, Matsushima K, Akazawa Y, Yamaguchi N, Ohnita K. Per-oral endoscopic myotomy: emerging indications and evolving techniques. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:175-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Baldaque-Silva F, Marques M, Vilas-Boas F, Maia JD, Sá F, Macedo G. New transillumination auxiliary technique for peroral endoscopic myotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:544-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Kravtsov IU, Antonov IV. [Surgical treatment of umbilical hernia in children]. Khirurgiia (Mosk). 1989;11:125-128. [PubMed] |

| 88. | Modayil R, Friedel D, Stavropoulos SN. Endoscopic suture repair of a large mucosal perforation during peroral endoscopic myotomy for treatment of achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:1169-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Saxena P, Chavez YH, Kord Valeshabad A, Kalloo AN, Khashab MA. An alternative method for mucosal flap closure during peroral endoscopic myotomy using an over-the-scope clipping device. Endoscopy. 2013;45:579-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Li H, Linghu E, Wang X. Fibrin sealant for closure of mucosal penetration at the cardia during peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM). Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E215-E216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Swanstrom LL, Kurian A, Dunst CM, Sharata A, Bhayani N, Rieder E. Long-term outcomes of an endoscopic myotomy for achalasia: the POEM procedure. Ann Surg. 2012;256:659-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Stavropoulos SN, Modayil R, Brathwaite CE, Halwan B, Taylor SI, Coppola T, Long D, Friedel D, Grendell JH. Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM) for Achalasia: Large Single-Center 4-Year Series by a Gastroenterologist With Emphasis on Objective Assessment of Emptying, GERD, LES Distensibility and Post-Procedural Pain. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:AB365. |

| 93. | Zhou PH, Cai MY, Yao LQ, Zhong YS, Ren Z, Xu MD, Chen WF, Qin XY. [Peroral endoscopic myotomy for esophageal achalasia: report of 42 cases]. Zhonghua Weichang Waike Zazhi. 2011;14:705-708. [PubMed] |

| 94. | Costamagna G, Marchese M, Familiari P, Tringali A, In- oue H, Perri V. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for oesophageal achalasia: preliminary results in humans. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:827-832. [PubMed] |

| 95. | Chiu PW, Wu JC, Teoh AY, Chan Y, Wong SK, Liu SY, Yung MY, Lam CC, Sung JJ, Chan FK. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for treatment of achalasia: from bench to bedside (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:29-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Hungness ES, Teitelbaum EN, Santos BF, Arafat FO, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ, Soper NJ. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between peroral esophageal myotomy (POEM) and laparoscopic Heller myotomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:228-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Minami H, Isomoto H, Yamaguchi N, Matsushima K, Akazawa Y, Ohnita K, Takeshima F, Inoue H, Nakao K. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for esophageal achalasia: clinical impact of 28 cases. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:43-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Von Renteln D, Fuchs KH, Fockens P, Bauerfeind P, Vassiliou MC, Werner YB, Fried G, Breithaupt W, Heinrich H, Bredenoord AJ. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of achalasia: an international prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:309-311.e1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 99. | Onimaru M, Inoue H, Ikeda H, Yoshida A, Santi EG, Sato H, Ito H, Maselli R, Kudo SE. Peroral endoscopic myotomy is a viable option for failed surgical esophagocardiomyotomy instead of redo surgical Heller myotomy: a single center prospective study. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:598-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Verlaan T, Rohof WO, Bredenoord AJ, Eberl S, Rösch T, Fockens P. Effect of peroral endoscopic myotomy on esophagogastric junction physiology in patients with achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:39-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Cai MY, Zhou PH, Yao LQ, Xu MD, Zhong YS, Li QL, Chen WF, Hu JW, Cui Z, Zhu BQ. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for idiopathic achalasia: randomized comparison of water-jet assisted versus conventional dissection technique. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1158-1165. [PubMed] |

| 102. | De Palma GD, Catanzano C. Removable self-expanding metal stents: a pilot study for treatment of achalasia of the esophagus. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S95-S96. [PubMed] |

| 103. | Coppola F, Gaia S, Rolle E, Recchia S. Temporary endoscopic metallic stent for idiopathic esophageal achalasia. Surg Innov. 2014;21:11-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Zhao JG, Li YD, Cheng YS, Li MH, Chen NW, Chen WX, Shang KZ. Long-term safety and outcome of a temporary self-expanding metallic stent for achalasia: a prospective study with a 13-year single-center experience. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:1973-1980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Zeng Y, Dai YM, Wan XJ. Clinical remission following endoscopic placement of retrievable, fully covered metal stents in patients with esophageal achalasia. Dis Esophagus. 2014;27:103-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Mukherjee S, Kaplan DS, Parasher G, Sipple MS. Expandable metal stents in achalasia--is there a role? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2185-2188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Cheng YS, Ma F, Li YD, Chen NW, Chen WX, Zhao JG, Wu CG. Temporary self-expanding metallic stents for achalasia: a prospective study with a long-term follow-up. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5111-5117. [PubMed] |

| 108. | De Palma GD, lovino P, Masone S, Persico M, Persico G. Self-expanding metal stents for endoscopic treatment of esophageal achalasia unresponsive to conventional treatments. Long-term results in eight patients. Endoscopy. 2001;33:1027-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Vela MF, Richter JE, Wachsberger D, Connor J, Rice TW. Complexities of managing achalasia at a tertiary referral center: use of pneumatic dilatation, Heller myotomy, and botulinum toxin injection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1029-1036. [PubMed] |

| 110. | Lopushinsky SR, Urbach DR. Pneumatic dilatation and surgical myotomy for achalasia. JAMA. 2006;296:2227-2233. [PubMed] |

| 111. | Snyder CW, Burton RC, Brown LE, Kakade MS, Finan KR, Hawn MT. Multiple preoperative endoscopic interventions are associated with worse outcomes after laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2095-2103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Finley CJ, Kondra J, Clifton J, Yee J, Finley R. Factors associated with postoperative symptoms after laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:392-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Rosemurgy AS, Morton CA, Rosas M, Albrink M, Ross SB. A single institution’s experience with more than 500 laparoscopic Heller myotomies for achalasia. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:637-645, 645-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Portale G, Costantini M, Rizzetto C, Guirroli E, Ceolin M, Salvador R, Ancona E, Zaninotto G. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic Heller-Dor surgery for esophageal achalasia: possible detrimental role of previous endoscopic treatment. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:1332-1339. [PubMed] |

| 115. | Ghoshal UC, Kumar S, Saraswat VA, Aggarwal R, Misra A, Choudhuri G. Long-term follow-up after pneumatic dilation for achalasia cardia: factors associated with treatment failure and recurrence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2304-2310. [PubMed] |