Published online Jun 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4365

Peer-review started: January 23, 2021

First decision: February 11, 2021

Revised: February 15, 2021

Accepted: March 29, 2021

Article in press: March 29, 2021

Published online: June 16, 2021

There are few reported cases of allograft nephrectomy due to malignancy followed by successful renal re-transplantation two years later. In this paper, we report a patient who underwent kidney re-transplantation after living donor graft nephrectomy due to de novo chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (ChRCC) involving the allograft kidney.

A 34-year-old man underwent living kidney transplantation at the age of 22 years for end-stage renal disease. Maintenance immunosuppression consisted of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and prednisone. Six years post-transplantation, at another hospital, ultrasonography revealed a small mass involving the upper pole of the graft. The patient declined further examination and treatment at this point. Seven years and three months post-transplantation, the patient experienced decreasing appetite, weight loss, gross hematuria, fatigue, and oliguria. Laboratory tests showed anemia (hemoglobin level was 53 g/L). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a large heterogeneous cystic-solid mass involving the upper pole of the renal allograft. Graft nephrectomy was performed and immunosuppressants were withdrawn. Histological and immunohistochemical features of the tumor were consistent with ChRCC. One year after allograft nephrectomy, low doses of tacrolimus and MMF were administered for preventing allosensitization. Two years after allograft nephrectomy, the patient underwent kidney re-transplantation. Graft function remained stable with no ChRCC recurrence in more than 2-years of follow-up.

De novo ChRCC in kidney graft generally has a good prognosis after graft nephrectomy and withdrawal of immunosuppression. Kidney re-transplantation could be a viable treatment. A 2-year malignancy-free period may be sufficient time before re-transplantation.

Core Tip: Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (ChRCC) is a rare malignancy of kidney allografts. This paper presents a case of de novo ChRCC arising primarily in an allograft kidney many years post-transplantation. It was successfully managed by allograft nephrectomy, and 2 years later, the patient underwent successful re-transplantation. Graft function was stable with no ChRCC recurrence beyond 2 years after re-transplantation. There are no guidelines for kidney re-transplantation after graft nephrectomy due to graft cancer. It remains a challenge to balance prevention of allosensitization and recurrence of cancer.

- Citation: Wang H, Song WL, Cai WJ, Feng G, Fu YX. Kidney re-transplantation after living donor graft nephrectomy due to de novo chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(17): 4365-4372

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i17/4365.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4365

Kidney transplantation is an effective treatment for patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and can significantly improve the long-term survival rate and the quality of life. However, the risk of cancer in renal transplant recipients is at least three to five times that in the general population[1]. Tumors may occur in the transplanted kidney, with the incidence of de novo renal cell carcinomas (RCC) in the renal graft at 0.18%[2]. Chromophobe RCC (ChRCC) is a rare variant of renal carcinoma. To the best of our knowledge, there are only five other case reports of pure ChRCC without any other cell type in a renal allograft[3-7], and one case describing mixed ChRCC and papillary carcinoma in a renal allograft[8]. Five of the above six patients underwent graft nephrectomy[3-6,8], and one patient underwent partial graft nephrectomy[7]. Tumor size in those patients ranged from 0.5 cm to 8.0 cm, and the interval before ChRCC diagnosis ranged from 5 to 15 years. A past history of cancer is not an absolute contraindication for kidney transplantation[9]. Herein, we report a case of secondary renal transplantation after living donor graft nephrectomy due to de novo ChRCC with no recurrence of cancer for more than 2 years after re-transplantation.

Seven years and three months post-transplantation (in February 2016), a 34-year-old man was admitted to the outpatient department of our hospital, complaining of decreasing appetite, weight loss, gross hematuria, fatigue, and oliguria (urinary volume was less than 200 mL).

The patient had undergone living kidney transplantation after hemodialysis for 2 mo at the age of 22 years on November 27, 2008 for ESRD. Biopsy of the patient’s native kidney was not performed, and etiology of the primary disease causing the ESRD was unclear. His mother, who was 41 years old at the time, donated her left kidney to him. The kidney graft was implanted at the right iliac fossa. The zero-point biopsy of graft showed unremarkable findings. Methylprednisolone was administered as induction therapy for a total dose of 2.5 g. Maintenance immunosuppression consisted of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and prednisone. The target trough level of tacrolimus was 8-10 ng/mL for 1 year post-operation. The creatinine level was 6.93 mg/dL before transplantation and decreased to 0.98 mg/dL 2 wk post-operation. The patient was discharged and followed regularly at another hospital.

Three and a half years post-transplantation (in May 2012), the patient was reviewed at another hospital. The creatinine level had increased to 1.92 mg/dL and urine test was positive for proteins (3+). The patient had no other discomfort or complaints, but he refused biopsy of the kidney graft. At that time, the result of panel reactive antibody (PRA) testing was negative, ultrasonography of the kidney graft was normal, and tacrolimus trough level was 6.2 ng/mL. Methylprednisolone was administered at a total dose of 1.5 g experientially (500 mg/d for three days), but the creatinine level increased gradually. Six years post-transplantation (in November 2014), the creatinine level of the patient further increased to 5.31 mg/dL, and biopsy of the kidney graft was performed at another hospital. Histopathological examination showed T-cell mediated acute rejection (Banff 1A) and sclerosing glomerulonephritis. Ultrasound of the kidney graft also showed a mass involving the upper pole of the graft, measuring 2 cm × 3 cm × 3 cm. However, the patient declined further examination and treatment.

The patient presented no other significant findings on a previous medical history.

On admission, the patient’s body weight was 37 kg, which had reduced by approximately 20 kg in 2 years. Physical examination showed pale palpebral conjunctiva and hyponychium, and a large mass could be palpated in the right abdominal region with clearly demarcated boundaries and partial mobility.

The patient was admitted on February 2, 2016. Laboratory tests showed a hemoglobin level of 53 g/L, white blood cell count of 5.03 × 109/L, platelet count of 212 × 109/L, and creatinine level of 11.23 mg/dL.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a giant heterogeneous cystic-solid mass, measuring 10 cm × 10 cm × 15 cm, involving the upper pole of the kidney allograft. The solid lesion of the tumor was enhanced by the contrast medium, whereas the cystic part of the mass was not enhanced (Figure 1). No lesion was found in the liver and both native kidneys. No abdominal and pelvic lymphadenopathy was revealed. Head CT showed no abnormalities. Malignancy of the kidney graft was suspected. The R.E.N.A.L nephrometry score[10] was 11x. Based on the TNM classification[11], the lesion was scored as stage II, T2bN0M0. Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of the mass was not performed due to concerns of malignant tumor metastasis along the passage path of the puncture needle.

As the kidney graft was non-functional and the comprehensive nephrometry score of the patient was high, radical graft nephrectomy was performed. All immuno-suppressants, including tacrolimus, MMF, and prednisone, were withdrawn postoperatively. The postoperative period was uneventful and regular hemodialysis treatment was performed three times per week.

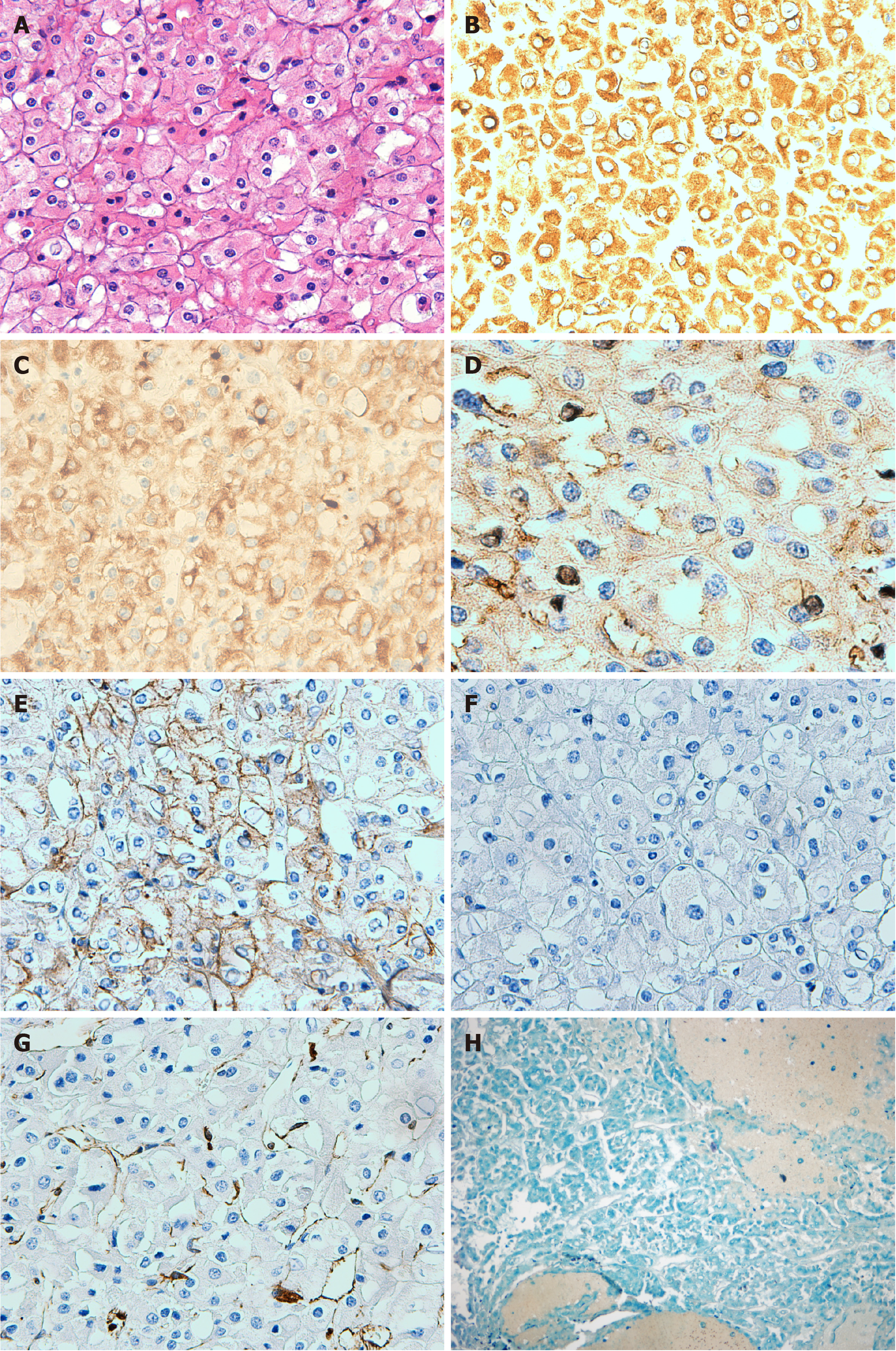

Macroscopically, the allograft nephrectomy specimen contained a well-defined cystic-solid mass, measuring 10 cm × 10 cm × 15 cm, located in the renal upper pole. Hemorrhage and necrosis were noted within the tumor. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed that the tumor cells comprised finely reticular cytoplasm and were strikingly large and polygonal. The tumor cell membrane was very clear. Tumor nuclei were polymorphic, often crumpled, and contained a perinuclear empty halo. Binucleation, wrinkled nuclear membranes, and variable nucleoli were noted (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemical staining was performed, which revealed a positive finding for cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 8, cluster of differentiation (CD) 117, and E-cadherin (Figure 2B-E), but negative finding for CD10 and vimentin (Figure 2F and G). Hale colloidal iron stain was positive (Figure 2H). Sarcomatoid components were not found on histologic analysis. Based on these characteristics, ChRCC of the renal allograft was diagnosed. The vascular and ureteric margins showed no invasion. Tumor HLA typing was performed. By comparing it to the donor and recipient, the origin of the tumor was confirmed to be from the donor graft. The patient’s mother underwent ultrasonography and CT of the abdomen and pelvis, but no abnormal lesion was found.

Ultrasonography of the abdomen and pelvis was performed on the patient every 3 mo postoperatively, and the findings were normal during the follow-up period. One year after allograft nephrectomy, CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not find any evidence of metastasis or recurrence. The patient expressed his wish to undergo secondary kidney transplantation. PRA was negative. To prevent the production of PRA and donor specific antibody (DSA), tacrolimus and MMF were administered at a dose of 1.0 mg/d and 500 mg/d, respectively. The patient was reinstated on the kidney transplant waiting list. The targeted trough level of tacrolimus during dialysis was around 3 mg/mL.

Two years after allograft nephrectomy, the patient underwent secondary kidney transplantation in August 2018. The donor organ was recovered from a 36-year-old male deceased donor who suffered brain injury caused by a traffic accident and had normal creatinine levels. HLA mismatch was two out of six alleles (-A, -B, and -DR), and crossmatch performed based complement-dependent cytotoxicity was 2%. The immunosuppression regimen was not different from that of other ordinary non-sensitized patients in our center. Induction medications included simulect (at a dose of 20 mg during surgery and at postoperative day 4) and methylprednisolone (500 mg before organ blood reperfusion and 500 mg/d for the next three days). Maintenance immunosuppression consisted of tacrolimus, enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium (EC-MPS), and prednisone. The patient received hemodialysis therapy due to delayed graft function for the first two postoperative weeks. His renal graft function then improved.

The patient was discharged with a creatinine level of 1.1 mg/dL in the third postoperative week. After discharge, the patient underwent routine outpatient review. Ultrasonography of the abdomen, pelvis, and urinary system was performed every 3 mo. CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed one and two years post-re-transplantation. The target trough concentration of tacrolimus was 8-10 ng/mL during the first year post-re-transplantation, and 6-8 ng/mL during the second year post-re-transplantation. EC-MPS dosage was 540 mg q12h during the first year, followed by 360 mg q12h to the present. The prednisone dosage was gradually reduced to 5 mg per day in 3 mo post-re-transplantation and maintained to the present. Until his most recent follow up, the renal graft function has remained stable with no signs of tumor recurrence. The most recent serum creatinine was 1.2 mg/dL. The patient’s mother has also remained healthy without evidence of malignancy.

In our patient, the initial kidney graft was donated by his mother. No lesion was found in either kidney of his mother before donation. The graft tumor occurred 6 years post-transplantation . HLA typing confirmed that the tumor originated from the donor graft. All of the above events implied that the tumor was a de novo malignancy in the graft. The mechanism for occurrence of de novo ChRCC in renal graft is unclear. Histopathologic examination is the gold standard for diagnosis. Positivity for cytokeratin 7 on immunohistochemistry and for Hale colloidal iron stains is a distinctive immunohistochemical and histological feature of ChRCC[3].

Radical nephrectomy of the allograft is the most used treatment for these patients and immunosuppressant withdrawal is often needed[3-8]. Immunosuppressive agents are used to prevent and treat rejection for transplantation, but some immuno-suppressive agents have been proven to have carcinogenic characteristics. Tacrolimus has a dose-dependent effect on tumor progression by interfering with TGF-β pathways[12]. Sirolimus and MMF have potential antioncogenic and antiproliferative roles and possess a lower tumor risk[1,13]. The specific effect of immunosuppressants on ChRCC in renal graft is unclear. ChRCC in native kidney is an indolent form of RCC with a low risk of metastasis, with 5- and 10-year disease-free survival rates of up to 83.9% and 77.9%, respectively[14]. In our patient, the tumor grew rapidly within 2 years after it was detected on ultrasonography in the kidney graft. The growth rate of ChRCC might be much faster in the immunosuppressed population than in the normal immune population. For recipients with de novo cancers post-transplantation, immunosuppressive dose reduction or withdrawal is crucial to prevent the progression and metastasis of life-threatening malignancies, because defective immune system of the recipient could be recovered and intact immune may play a role against malignant cells and prevent malignancy recurrence[1]. In our patient, immunosuppressants were withdrawn immediately after graft nephrectomy.

For native kidney ChRCC, larger tumors and sarcomatoid differentiation of ChRCC are risk factors for metastasis[15]. For renal graft ChRCC, the risk factors for metastasis are unclear. Our patient had a large tumor accompanied with hemorrhage and necrosis, but sarcomatoid differentiation was not seen. No metastasis had occurred systemically before and after transplant nephrectomy. Compared with dialysis, re-transplantation could offer a significant survival benefit for the recipient and should be pursued. Malignancy history is not an absolute contraindication for kidney transplantation[9]. Barrou et al[16] reported a case of renal graft carcinoma transmitted by the donor with no distinguishable morphological type 4 mo post-transplantation. The graft was immediately removed and immunosuppression was discontinued. Two years later, the patient underwent re-transplantation and the second donor shared no HLA antigens with the first one. Tydén et al[17] reported a case of de novo moderately differentiated papillary tumor in living donor kidney graft 9 years post-transplantation. Graft nephrectomy was performed and immunosuppression was withdrawn. The authors mentioned that the patient underwent a second living donor kidney transplantation 7 mo later without detailed description. To the best of our knowledge, our patient is the first reported case of kidney re-transplantation after renal allograft resection due to de novo ChRCC in graft.

Allograft nephrectomy and immunosuppression withdrawal may result in the development of HLA antibodies and reduce the chance of kidney re-transplantation[18]. Low trough levels of tacrolimus (≥ 3 ng/mL) could prevent the occurrence of DSA and nondonor-specific HLA antibodies in patients without allograft nephrectomy and increase re-transplantation matchability up to 2 years after the failure of the first graft[19]. For patients with allograft nephrectomy due to malignancy, with regards to balancing between protection against PRA production and malignancy recurrence, there is no definite answer. In our patient, tacrolimus and MMF were administered to prevent the development of allosensitization 1 year after allograft nephrectomy. Tacrolimus, EC-MPS, and prednisone were administered for maintenance immunosuppression after kidney re-transplantation. Before and after kidney re-transplantation, the patient had negative findings on PRA test and did not experience ChRCC recurrence.

The KDIGO Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend that the ideal timing of kidney transplantation after potentially curative treatment for cancer is dependent on the cancer type and stage on initial diagnosis[20]. For patients with native kidney cancer, no waiting time is needed for incidentaloma (< 3 cm), and the recommended waiting time for early malignancy and for large and invasive cancer are 2 years and at least 5 years, respectively[20]. Our patient had a large tumor and received re-transplantation after 2 years of being cancer-free. No ChRCC recurred in more than 2 years of follow-up.

By reviewing our case, some questions arose. First, is it appropriate to administer immunosuppressants for avoiding allosensitization after graft nephrectomy and what is the ideal timing? After graft nephrectomy and immunosuppressant withdrawal, if tumor cells remained in the recipient’s body, the immune system of the recipient could reject the tumor cells drastically within a very short time[16]. The second question is should the waiting time for re-transplantation be shorter in patients with graft tumors than in patients with native kidney cancer history? No guidelines are available yet for kidney re-transplantation after graft nephrectomy due to graft cancer. More studies are needed in the future to address these issues.

De novo ChRCC in kidney graft generally shows a good prognosis. Kidney re-transplantation could be a viable treatment. Waiting for a 2-year malignancy free period might be sufficient before re-transplantation.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Transplantation

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Parajuli S, Yamaguchi K S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Wong G, Chapman JR. Cancers after renal transplantation. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2008;22:141-149. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tillou X, Guleryuz K, Collon S, Doerfler A. Renal cell carcinoma in functional renal graft: Toward ablative treatments. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2016;30:20-26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Greco AJ, Baluarte JH, Meyers KE, Sellers MT, Suchi M, Biegel JA, Kaplan BS. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma in a pediatric living-related kidney transplant recipient. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:e105-e108. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Althaf MM, Al-Sunaid MS, Abdelsalam MS, Alkorbi LA, Al-Hussain TO, Dababo MA, Haq N. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma occurring in the renal allograft of a transplant recipient presenting with weight loss. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27:139-143. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Alharbi A, Al Turki MS, Aloudah N, Alsaad KO. Incidental eosinophilic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma in renal allograft. Case Rep Transplant. 2017;2017:4232474. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ajabnoor R, Al-Sisi E, Zafer G, Al-Maghrabi J. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma in renal allograft: Case report. Life Sci J. 2014;11:9-14. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Troxell ML, Higgins JP. Renal cell carcinoma in kidney allografts: histologic types, including biphasic papillary carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2016;57:28-36. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ploussard G, Chambade D, Meria P, Gaudez F, Tariel E, Verine J, De Bazelaire C, Peraldi MN, Glotz D, Desgrandchamps F, Mongiat-Artus P. Biopsy-confirmed de novo renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in renal grafts: a single-centre management experience in a 2396 recipient cohort. BJU Int. 2012;109:195-199. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dahle DO, Grotmol T, Leivestad T, Hartmann A, Midtvedt K, Reisæter AV, Mjøen G, Pihlstrøm HK, Næss H, Holdaas H. Association between pretransplant cancer and survival in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2017;101:2599-2605. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kutikov A, Uzzo RG. The R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry score: a comprehensive standardized system for quantitating renal tumor size, location and depth. J Urol. 2009;182:844-853. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1335] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1475] [Article Influence: 98.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471-1474. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5537] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6108] [Article Influence: 436.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Maluccio M, Sharma V, Lagman M, Vyas S, Yang H, Li B, Suthanthiran M. Tacrolimus enhances transforming growth factor-beta1 expression and promotes tumor progression. Transplantation. 2003;76:597-602. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 195] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wimmer CD, Rentsch M, Crispin A, Illner WD, Arbogast H, Graeb C, Jauch KW, Guba M. The janus face of immunosuppression - de novo malignancy after renal transplantation: the experience of the Transplantation Center Munich. Kidney Int. 2007;71:1271-1278. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stec R, Grala B, Maczewski M, Bodnar L, Szczylik C. Chromophobe renal cell cancer--review of the literature and potential methods of treating metastatic disease. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:134. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Casuscelli J, Becerra MF, Seier K, Manley BJ, Benfante N, Redzematovic A, Stief CG, Hsieh JJ, Tickoo SK, Reuter VE, Coleman JA, Russo P, Ostrovnaya I, Hakimi AA. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: results from a large single-institution series. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2019; 17: 373-379. e4. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Barrou B, Bitker MO, Delcourt A, Ourahma S, Richard F. Fate of a renal tubulopapillary adenoma transmitted by an organ donor. Transplantation. 2001;72:540-541. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tydén G, Wernersson A, Sandberg J, Berg U. Development of renal cell carcinoma in living donor kidney grafts. Transplantation. 2000;70:1650-1656. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lachmann N, Schönemann C, El-Awar N, Everly M, Budde K, Terasaki PI, Waiser J. Dynamics and epitope specificity of anti-human leukocyte antibodies following renal allograft nephrectomy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:1351-1359. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lucisano G, Brookes P, Santos-Nunez E, Firmin N, Gunby N, Hassan S, Gueret-Wardle A, Herbert P, Papalois V, Willicombe M, Taube D. Allosensitization after transplant failure: the role of graft nephrectomy and immunosuppression - a retrospective study. Transpl Int. 2019;32:949-959. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chadban SJ, Ahn C, Axelrod DA, Foster BJ, Kasiske BL, Kher V, Kumar D, Oberbauer R, Pascual J, Pilmore HL, Rodrigue JR, Segev DL, Sheerin NS, Tinckam KJ, Wong G, Knoll GA. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline on the evaluation and management of candidates for kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2020;104:S11-S103. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 237] [Article Influence: 79.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |