Published online May 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i14.3449

Peer-review started: December 8, 2020

First decision: January 24, 2021

Revised: February 10, 2021

Accepted: March 4, 2021

Article in press: March 4, 2021

Published online: May 16, 2021

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) of the endometrium is an uncommon and highly aggressive tumor that has not been comprehensively characterized. We report a case of pure endometrial LCNEC and review the current literature of similar cases to raise awareness of the histological features, treatment, and prognosis of this tumor.

We report the case of a 73-year-old woman who presented with irregular postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. Ultrasonography showed an enlarged uterus and a 5.1 cm × 3.3 cm area of medium and low echogenicity in the uterine cavity. Biopsy by dilatation and curettage suggested poorly differentiated carcinoma. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a heterogeneously enhanced uterine tumor with diffuse infiltration of the posterior wall of the uterine myometrium and enlarged pelvic lymph nodes. The patient underwent a hysterectomy and bilateral adnexal resection. Gross observation revealed an ill-defined white solid mass of the posterior wall of the uterus infiltrating into the serosa with multiple solid nodules on the serous surface. Microscopically, the tumor cells showed neuroendocrine morphology (organoid nesting). Immunohistochemistry revealed the tumor cells were diffusely positive for the neuroendocrine markers CD56, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin. Thus, the tumor was diagnosed as stage IIIC endometrial LCNEC.

Pathologic findings and immunohistochemistry are essential in making a diagnosis of endometrial LCNEC.

Core Tip: We report the diagnostic and therapeutic experience of a 73-year-old patient with pure endometrial large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. This article explores the histological features, differential diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of this tumor and reviews the current literature of similar cases to provide a reference for the diagnosis and treatment of endometrial large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

- Citation: Du R, Jiang F, Wang ZY, Kang YQ, Wang XY, Du Y. Pure large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma originating from the endometrium: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(14): 3449-3457

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i14/3449.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i14.3449

Neuroendocrine carcinoma arising from the endometrium is an uncommon entity, accounting for less than 1% of endometrial carcinoma, and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) is very rare[1]. LCNEC has an aggressive natural history, a high propensity to metastasize, and poor survival outcomes[1]. To the authors’ knowledge, only 21 cases of LCNEC in the uterine corpus have been published[2-12], and only 12 of these were pure LCNEC (Table 1). Due to the small number of reported cases, knowledge of LCNEC is limited, and the tumor may be difficult to diagnose. Here, we present a case of LCNEC arising in the endometrium. Our findings should raise awareness of the histological features, treatment, and prognosis of this tumor.

| Case | Ref. | Age in yr | Presenting symptom | Histology | Immunoprofile positivity | FIGO stage | Surgery | Treatment | Outcome |

| 1 | Nguyen et al[9] | 70 | PMB | Pure LCNEC | Synaptophysin, chromogranin A, CD56, EMA | IVB | TAH, BSO, OMT | Etoposide, cisplatin | NED 6 mo |

| 2 | Nguyen et al[9] | 71 | PMB | Pure LCNEC | Synaptophysin, chromogranin A, CD56, P53, P16,PR | IVB | TAH, BSO, LND, OMT | Etoposide, cisplatin, octreotide | DOD 1 mo |

| 3 | Nguyen et al[9] | 52 | PMB | Pure LCNEC | NSE, synaptophysin | IC | TAH, BSO | Etoposide, cisplatin | DOD 7 mo |

| 4 | Kobayashi et al[10] | 52 | Abdominal pain | Pure LCNEC | Synaptophysin, chromogranin A, CD56 | IIIC | TAH, BSO, LND | Irinotecan, cisplatin, RT | DOD 10 mo |

| 5 | Makihara et al[28] | 73 | Abdominal distension | Pure LCNEC | Synaptophysin, chromogranin A, NSE, P53 | IVB | Refused surgery | Refused chemotherapy | DOD 5 wk |

| 6 | Makihara et al[28] | 73 | PMB | Pure LCNEC | Synaptophysin, chromogranin A, CD56, P53 | IIIC | TAH, BSO, LND, OMT | Cisplatin, irinotecan | Recurrence at 6 mo |

| 7 | Ogura et al[29] | 52 | Menorrhagia | Pure LCNEC | Synaptophysin, CD56, Ki67 | IIIC | None | None | DOD 1 mo |

| 8 | Mulvany et al[27] | 50 | PMB | Pure LCNEC | NSE, synaptophysin | IIIC | TAH, BSO, LND, OMT | Carboplatin, etoposide, RT | AWD 12 mo |

| 9 | Tu et al[15] | 51 | PMB | Pure LCNEC | CK, P53, CD56, synaptophysin | IVB | TAH, BSO, OMT, suboptimal debulking | Cisplatin, etoposide | DOD 3 mo |

| 10 | Shahabi et al[3] | 59 | PMB | Pure LCNEC | NSE, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, CD56 | IIIC | TAH, BSO, LND, OMT, suboptimal debulking | Carboplatin, paclitaxel, doxorubicin, etoposide, cisplatin, octreotide | DOD 12 mo |

| 11 | Suh et al[22] | 61 | Abdominal pain and rapid uterine enlargement | Pure LCNEC | synaptophysin, CD56 | IIIB | TAH, BSO, OMT | Etoposide/cisplatin, irinotecan/cisplatin, fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, RT | DOD 23 mo |

| 12 | Present case | 73 | PMB | Pure LCNEC | Cytokeratin AE1/AE3, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, CD56, P16 | IIIC | TAH, BSO | Paclitaxel, liposome, carboplatin | NED 15 mo |

A 73-year-old woman was admitted to Liaocheng People’s Hospital in October 2019 due to irregular postmenopausal vaginal bleeding.

The patient had undergone natural menopause 32 yrs ago and had a history of irregular vaginal bleeding in the 3 mo prior to admission. Initially, bleeding was intermittent, lasting for intervals of 2 d. Blood loss was minimal, there was no abdominal pain, and the patient did not seek medical treatment. Twenty days before admission, the patient experienced continuous vaginal bleeding. Blood loss was similar to menstruation, and there was occasional abdominal pain. Two weeks later, the patient experienced massive bleeding and was treated in the gynecology clinic of Liaocheng People’s Hospital.

The patient’s medical history was unremarkable.

After admission to the hospital, the patient’s temperature was 36.6 ℃, heart rate was 76 bpm, respiratory rate was 18 breaths per minute, and blood pressure was 142/73 mmHg. On gynecological examination, when the patient held her breath, the posterior wall of the vagina compressed and partially protruded outside the vagina. The cervix was atrophied, and the uterus was enlarged.

Blood analysis, biochemistry, and urinalysis were normal. Electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, and arterial blood gas were normal.

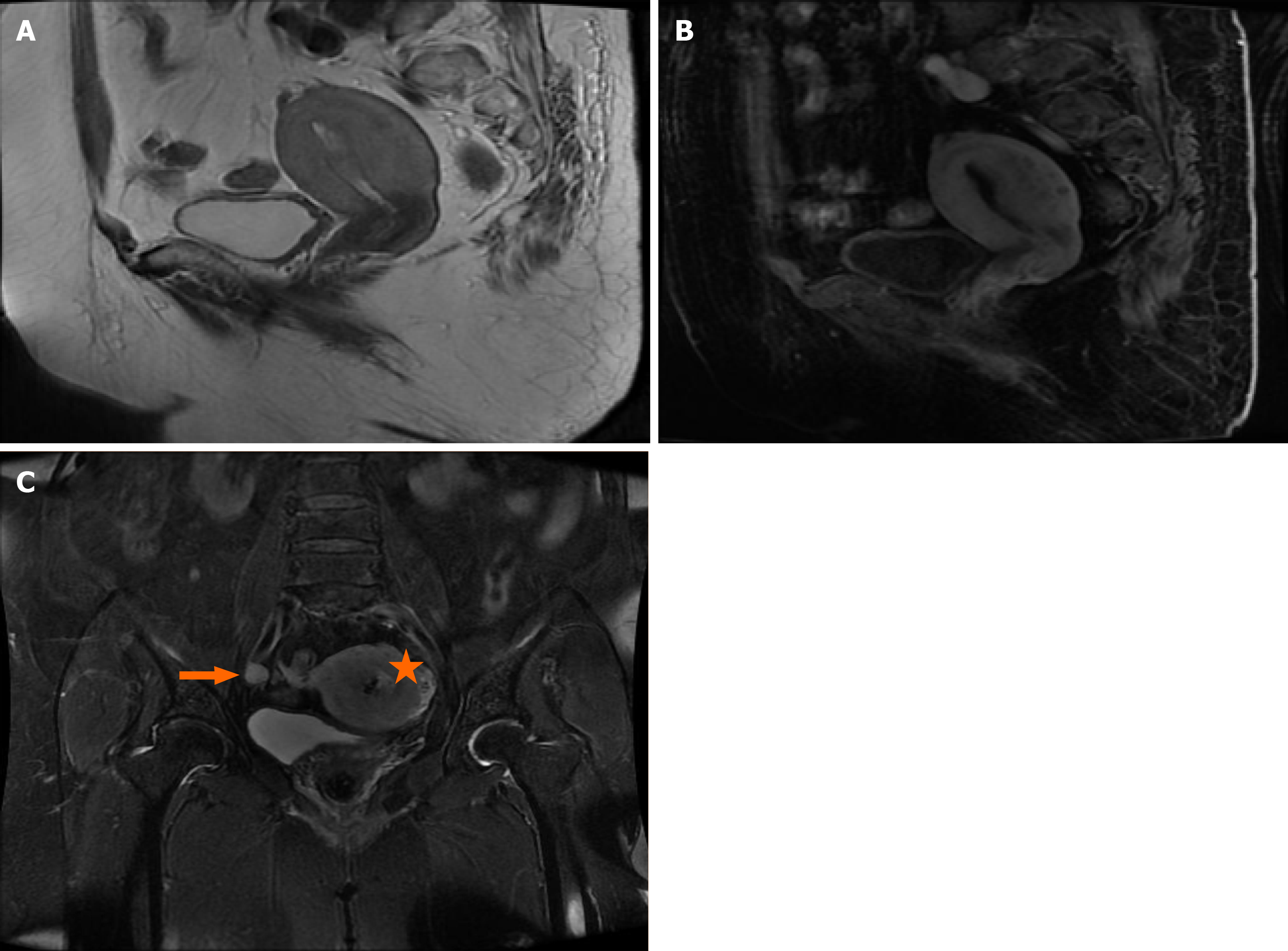

Ultrasonography showed an enlarged uterus and a 5.1 cm × 3.3 cm area of medium and low echogenicity in the uterine cavity. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated an enlarged uterus and uterine cavity, and the endometrium was thickened, irregular, and protruded into the uterine cavity. A coronal contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan revealed a heterogeneously enhanced uterine tumor with diffuse infiltration of the posterior wall of the uterine myometrium and local roughness of the serosa. Lymph node metastasis was suspected as the internal and external iliac lymph nodes were enlarged. The largest was approximately 1.4 cm and lay along the right external iliac artery. The right internal iliac lymph nodes were partially necrotic (Figure 1). Diagnostic imaging showed no detectable invasion of the tumor into the bladder or rectum.

Biopsy by dilatation and curettage suggested poorly differentiated carcinoma. The patient underwent a hysterectomy and bilateral adnexal resection. Pelvic lymph node dissection was not performed as the patient was obese. Gross observations revealed an ill-defined white solid mass that arose from the endometrium and extended through the full thickness of the posterior wall of the myometrium to the uterine serosa. Multiple solid nodules were scattered on the serosa; the largest was 1 cm × 0.8 cm × 0.5 cm.

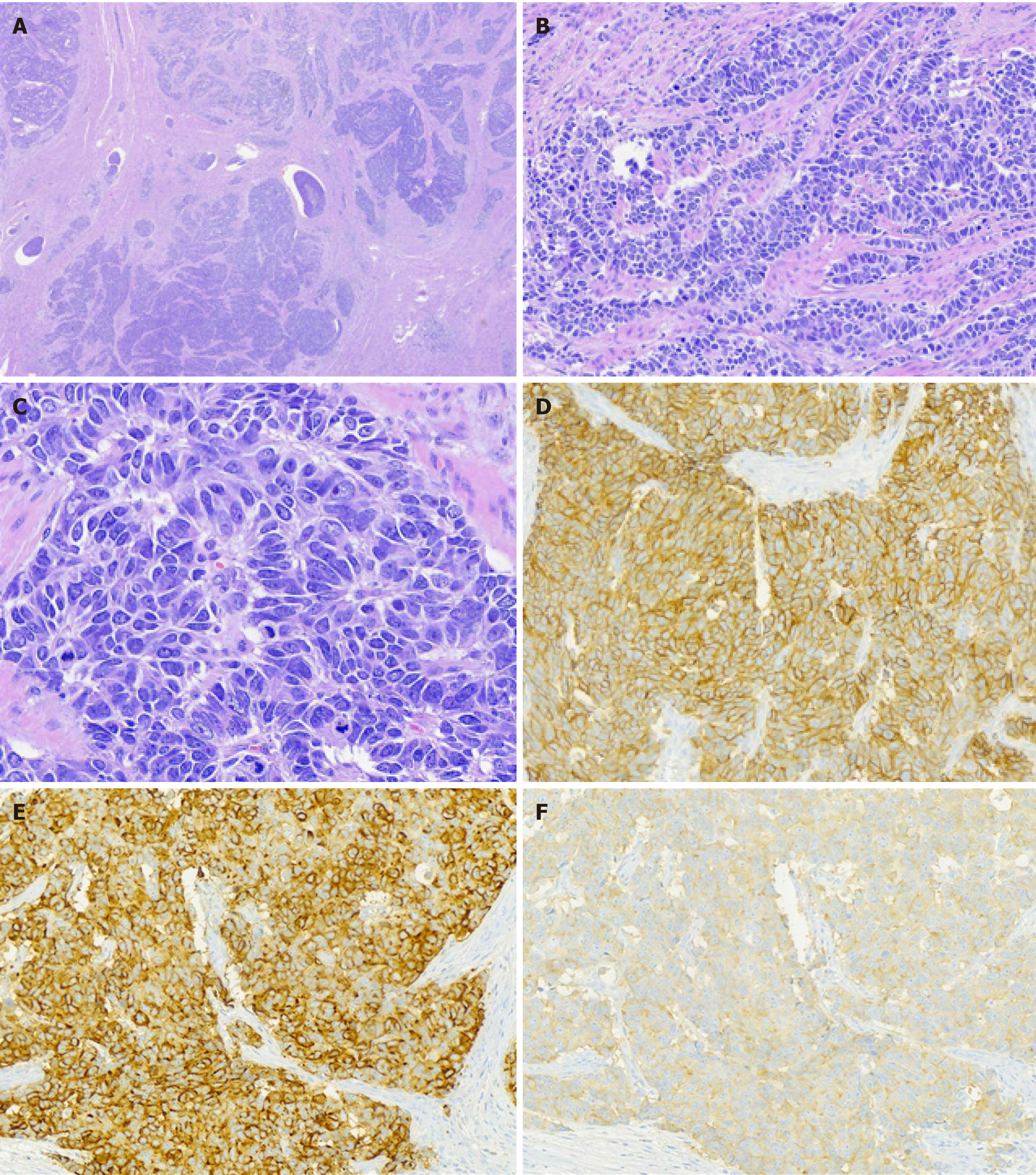

Microscopically, the poorly differentiated carcinoma infiltrated the muscular layer of the posterior wall of the uterine body to the serosa and did not invade the inner orifice of the cervix. Histologic characteristics included polygonal cells with abundant cytoplasm and a granular eosinophilic or basophilic appearance, large nuclei, prominent nucleoli, “salt and pepper” chromatin, thick nuclear membranes, and ≥ 10 mitoses/high power field without obvious necrosis. The tumor cells showed neuroendocrine morphology (organoid nesting, trabeculae, palisading, or a rosette-like growth pattern) mixed with a solid diffuse pattern (Figure 2). There was obvious vascular invasion and occasional perineural invasion.

Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, CD56 (Figure 2) and P16 and negative for P53, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and CD10. The Ki-67 index was approximately 80%. There was no loss of expression of mismatch repair proteins (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6).

Based on the histological characteristics and results of the immunohistochemical staining, the tumor was diagnosed as LCNEC. Bilateral ovaries and fallopian tubes were not involved, but a small number of tumor cells were found in pelvic lavage fluid. The clinical postoperative stage was IIIC (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics).

The patient’s recovery after surgery was uneventful. She received four cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel liposome (240 mg) and lobaplatin (50 mg) over a 3 wk interval at Liaocheng People’s Hospital.

The response to chemotherapy was mild, and there was no obvious alopecia or gastrointestinal reaction. After the fourth chemotherapy treatment, computed tomography of the chest and abdomen and abdominal ultrasound showed no abnormalities. Six months later, computed tomography of the chest and abdomen, abdominal ultrasound, and gynecological examination showed no recurrence or metastasis. At present, after 15 mo, the patient is alive with no evidence of disease.

Most reports on LCNEC describe lung malignancies, even though LCNEC only account for 3% of lung cancers. LCNEC of the female genital tract are usually found in the uterine cervix and ovary and rarely involve the endometrium[13]. Endometrial LCNEC may be formed by LCNEC alone or as composites with varying proportions of other tumors, usually endometrioid carcinoma. Previous studies have described the clinicopathological features of endometrial neuroendocrine carcinoma. Pocrnich et al[14] reported on 25 cases, including large cell type, small cell type, or a mixture of both. Of these, 22 cases had a LCNEC component and 3 cases had a small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma component[14]. Rivera et al[1] reported a case of LCNEC associated with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. In the present case, the tumor was pure LCNEC.

A literature review revealed published studies describing endometrial LCNEC included patients aged 51 to 73 years (median: 60 years; mean: 61 years) (Table 1), suggesting the disease mainly affects older postmenopausal women. The most common clinical manifestation of endometrial LCNEC was abnormal or postmenopausal bleeding. The maximum reported endometrial LCNEC tumor dimensions ranged from 0.8 to 12 cm (median: 6.0 cm). Most publications showed endometrial LCNECs had neuroendocrine morphology with an insular (organoid nesting) and admixed solid (diffuse) growth pattern. Most tumors had high mitotic activity, areas of necrosis, and vascular invasion and expressed at least one neuroendocrine marker (chromogranin, synaptophysin, or CD56)[14,15]. The Ki-67 proliferation index was very high (> 80%)[16,17]. Immunohistochemical staining of four cases of pure LCNEC, three cases of LCNEC associated with endometrioid carcinoma, and one case of small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma associated with endometrioid carcinoma demonstrated abnormalities of mismatch repair protein expression[14]. In the present case, the tumor was diffusely and strongly positive for synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and CD56, and there was no loss of mismatch repair expression.

The genetic profile of endometrial LCNEC is unknown. However, endometrioid carcinoma and endometrial LCNEC share a gene mutation signature with identical alterations in phosphatase and tensin homolog, PIK3CA, and fibroblast growth factor receptor 3, suggesting a common origin[18].

Routine tissue sampling may misdiagnose or miss endometrial LCNEC. Endometrial biopsy provided only one pathologic diagnosis among 20 cases of endometrial LCNEC, even though endometrial assessment by biopsy or sampling of endometrial cells has a sensitivity of 81% for detecting endometrial carcinoma and atypical hyperplasia in women with abnormal uterine bleeding[19,20]. Consistent with this, consensus suggests that LCNEC of the lung should not be made on cytology or biopsy alone with the final diagnosis based on resected specimens[21].

Due to its rarity, there is no standard therapy for LCNEC[22], and most clinical recommendations are relevant to LCNEC of the lung or cervix, including the use of first-line chemotherapy with irinotecan/cisplatin therapy[22]. For early stage endometrial LCNEC, consensus favors surgery followed by chemotherapy with etoposide and platinum-based agents[20]. Surgical approaches to endometrioid histology include hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and lymph node dissection, while omentectomy is performed for nonendometrioid carcinoma[22]. In the studies identified in our literature review, six patients with endometrial LCNEC were treated with standard surgical methods relevant to nonendometrioid carcinoma with various outcomes. Complete surgery provided better outcomes compared to incomplete surgery[23]. At present, there is no established first-line chemotherapy regimen for endometrial LCNEC. Etoposide and cisplatin are generally preferred in LCNEC of the cervix with an 83% recurrence free survival reported at 3 yrs[24]. Paclitaxel and platinum-based chemotherapy has become a first-line chemotherapy regimen for gynecological malignant tumors such as endometrial cancer and ovarian cancer, especially for patients with aggressive tumors who have a high risk of recurrence. Lobaplatin is more effective for controlling disease progression and associated with less toxicity and better patient quality of life than carboplatin[25,26]. Therefore, this patient was treated with liposomal paclitaxel combined with lobaplatin, which achieved good efficacy with mild side effects.

Differential diagnosis for endometrial LCNEC includes grade 3 endometrioid carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, and primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Grade 3 endometrioid carcinoma express neuroendocrine markers but lack nest-like, trabecular, or ribbon-like polygonal cells. Undifferentiated carcinomas resemble LCNEC but may show diffuse staining for neuroendocrine markers[6]. LCNECs are identified when neuroendocrine markers are expressed in > 10% of tumor cells. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor usually stain positive for synaptophysin but are typically chromogranin negative and show neuroectodermal differentiation (fibrillary background, rosettes, ganglion cells, astrocyte-like cells) and are negative for cytokeratins[8]. Endometrial LCNECs do not show specific characteristics on imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging findings resemble other poorly differentiated carcinomas and uterine sarcoma, showing an ill-defined endometrial-myometrial border and a heterogeneous mass with necrosis and hemorrhage[27]. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging has clinical utility for assessing the extent of endometrial LCNEC.

Stage is an important predictor of prognosis in patients with cancer[22]. Among the studies identified in our literature review, 11 endometrial LCNECs were stage III-IV (91.7%) and 1 was stage IC. Among the 12 patients, 8 (66.7%) died within 7.3 mo of diagnosis. However, several studies show International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage was not a significant predictor of prognosis in patients with endometrial LCNECs on multivariate analysis[22,23], possibly because neuroendo

Endometrial LCNEC is extremely uncommon, especially pure LCNEC, which is likely under-reported and misdiagnosed. Correct diagnosis of endometrial LCNEC is important as it is a highly aggressive tumor that is associated with poor survival outcomes, but there is no evidence-based therapeutic regimen. Here, we describe a case of pure endometrial LCNEC and review the current literature of similar cases to raise awareness of the histological features, treatment, and prognosis of this tumor.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tajiri K S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Rivera G, Niu S, Chen H, Fahim D, Peng Y. Collision Tumor of Endometrial Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma and Low-Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2020;28:569-573. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Erhan Y, Dikmen Y, Yucebilgin MS, Zekioglu O, Mgoyi L, Terek MC. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine corpus metastatic to brain and lung: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2004;25:109-112. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Shahabi S, Pellicciotta I, Hou J, Graceffa S, Huang GS, Samuelson RN, Goldberg GL. Clinical utility of chromogranin A and octreotide in large cell neuro endocrine carcinoma of the uterine corpus. Rare Tumors. 2011;3:e41. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alkushi A, Irving J, Hsu F, Dupuis B, Liu CL, Rijn M, Gilks CB. Immunoprofile of cervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas using a tissue microarray. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:271-277. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 103] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tafe LJ, Garg K, Chew I, Tornos C, Soslow RA. Endometrial and ovarian carcinomas with undifferentiated components: clinically aggressive and frequently underrecognized neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:781-789. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 151] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Taraif SH, Deavers MT, Malpica A, Silva EG. The significance of neuroendocrine expression in undifferentiated carcinoma of the endometrium. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009;28:142-147. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bartosch C, Manuel Lopes J, Oliva E. Endometrial carcinomas: a review emphasizing overlapping and distinctive morphological and immunohistochemical features. Adv Anat Pathol. 2011;18:415-437. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Euscher ED, Deavers MT, Lopez-Terrada D, Lazar AJ, Silva EG, Malpica A. Uterine tumors with neuroectodermal differentiation: a series of 17 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:219-228. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nguyen ML, Han L, Minors AM, Bentley-Hibbert S, Pradhan TS, Pua TL, Tedjarati SS. Rare large cell neuroendocrine tumor of the endometrium: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:651-655. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kobayashi A, Yahata T, Nanjo S, Mizoguchi M, Yamamoto M, Mabuchi Y, Yagi S, Minami S, Ino K. Rapidly progressing large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma arising from the uterine corpus: A case report and review of the literature. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6:881-885. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Froio E, D’Adda T, Fellegara G, Martella E, Caruana P, Pruneri G, Pesci A, Rindi G. Uterine carcinosarcoma metastatic to the lung as large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma with synchronous sarcoid granulomatosis. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:371-377. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ono K, Yokota NR, Yoshioka E, Noguchi A, Washimi K, Kawachi K, Miyagi Y, Kato H, Yokose T. Metastatic large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung arising from the uterus: A pitfall in lung cancer diagnosis. Pathol Res Pract. 2016;212:654-657. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Albores-Saavedra J, Martinez-Benitez B, Luevano E. Small cell carcinomas and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the endometrium and cervix: polypoid tumors and those arising in polyps may have a favorable prognosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:333-339. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pocrnich CE, Ramalingam P, Euscher ED, Malpica A. Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Endometrium: A Clinicopathologic Study of 25 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:577-586. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tu YA, Chen YL, Lin MC, Chen CA, Cheng WF. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the endometrium: A case report and literature review. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;57:144-149. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lv K, Zhang CL, Xu MS. Primary Castleman’s disease in the liver: A case report and literature review. Mol Clin Oncol. 2018;8:575-578. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Terada T. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma with sarcomatous changes of the endometrium: a case report with immunohistochemical studies and molecular genetic study of KIT and PDGFRA. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206:420-425. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ariura M, Kasajima R, Miyagi Y, Ishidera Y, Sugo Y, Oi Y, Hayashi H, Shigeta H, Miyagi E. Combined large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and endometrioid carcinoma of the endometrium: a shared gene mutation signature between the two histological components. Int Cancer Conf J. 2017;6:11-15. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dijkhuizen FP, Mol BW, Brölmann HA, Heintz AP. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in the diagnosis of patients with endometrial carcinoma and hyperplasia: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2000;89:1765-1772. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Jenny C, Kimball K, Kilgore L, Boone J. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the endometrium: a report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2019;28:96-100. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hiroshima K, Mino-Kenudson M. Update on large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2017;6:530-539. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Suh DS, Kwon BS, Hwang SY, Lee NK, Choi KU, Song YJ, Kim KH. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma arising from uterine endometrium with rapidly progressive course: report of a case and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:1412-1417. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Matsumoto H, Shimokawa M, Nasu K, Shikama A, Shiozaki T, Futagami M, Kai K, Nagano H, Mori T, Yano M, Sugino N, Fujimoto E, Yoshioka N, Nakagawa S, Shimada M, Tokunaga H, Yamada Y, Tsuruta T, Tasaki K, Nishikawa R, Kuji S, Motohashi T, Ito K, Yamada T, Teramoto N. Clinicopathologic features, treatment, prognosis and prognostic factors of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the endometrium: a retrospective analysis of 42 cases from the Kansai Clinical Oncology Group/Intergroup study in Japan. J Gynecol Oncol. 2019;30:e103. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zivanovic O, Leitao MM Jr, Park KJ, Zhao H, Diaz JP, Konner J, Alektiar K, Chi DS, Abu-Rustum NR, Aghajanian C. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: Analysis of outcome, recurrence pattern and the impact of platinum-based combination chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:590-593. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 113] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kim HS, Kim JW, Wu HG, Chung HH, Park NH, Song YS, Kang SB, Lee HP. Comparison of the efficacy between paclitaxel/carboplatin and doxorubicin/cisplatin for concurrent chemoradiation in intermediate- or high-risk endometrioid endometrial cancer: a single institution experience. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36:598-604. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wang W, Liu M, Ding B. Comparison of the short-term efficacy and serum markers between lobaplatin/paclitaxel- And carboplatin/paclitaxel-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patient with ovarian cancer. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2021;46:166-172. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mulvany NJ, Allen DG. Combined large cell neuroendocrine and endometrioid carcinoma of the endometrium. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:49-57. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Makihara N, Maeda T, Nishimura M, Deguchi M, Sonoyama A, Nakabayashi K, Kawakami F, Itoh T, Yamada H. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma originating from the uterine endometrium: a report on magnetic resonance features of 2 cases with very rare and aggressive tumor. Rare Tumors. 2012;4:e37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ogura J, Adachi Y, Yasumoto K, Okamura A, Nonogaki H, Kakui K, Yamanoi K, Suginami K, Koyama T, Ikehara S. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma arising in the endometrium: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2018;8:571-574. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |