Published online Feb 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i4.473

Peer-review started: November 28, 2018

First decision: December 15, 2018

Revised: January 4, 2019

Accepted: January 26, 2019

Article in press: January 26, 2019

Published online: February 26, 2019

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) of the thyroid gland is a rarely presented tumor that offers poor prognosis. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there currently exist only 28 known cases described in the literature (limited to English).

Herein a case is reported of a 60-year-old female patient who had an LMS of the thyroid, which was accompanied by periodic dysphonia and breathing disorder as well as the feeling of pressure in the chest and neck. At the time the disease was diagnosed, no metastases were detected. Prior to the diagnosis, the patient experienced a uterine adenocarcinoma that had been treated by surgical procedure and radiotherapy. For the LMS, a total thyroidectomy was performed, followed by radiotherapy. Since metastases were also discovered in the lungs, sternum, and femur, chemotherapy was administered as well. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells in the thyroid indicated positively for alpha smooth muscle actin, calponin, and H-caldesmon, but were negative for CD34, p63, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and Epstein-Barr virus.

Although the etiology of the LMS is as of yet unknown, prior malignancy and radiation should be considered as risk factors.

Core tip: Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) of the thyroid gland is a rare tumor with only 28 cases described in the English literature. Etiology of leiomyosarcoma is still unknown. We present a case of LMS in which the patient had a prior malignancy and radiotherapy along with two similar cases previously described. Therefore, we hypothesize that prior malignancy and radiotherapy is a risk factor. Immunohistochemistry plays a crucial role in the diagnosis, and we provided substantial discussion about differential diagnosis of thyroid tumors, alongside with our microscopic findings that provide practical value for the daily practice of pathology.

- Citation: Vujosevic S, Krnjevic D, Bogojevic M, Vuckovic L, Filipovic A, Dunđerović D, Sopta J. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid gland with prior malignancy and radiotherapy: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(4): 473-481

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i4/473.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i4.473

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is a malignant tumor derived from or showing evidence of differentiation towards smooth muscle[1]. Most commonly, it is found in the pelvic area, gastrointestinal tract, or retroperitoneal area[2]. A review of the English literature suggests that LMS is rare, and there have only been 28 such cases described in the thyroid gland. The most common sign is a growing mass in the neck[3-5]. There have been only two known cases that had recorded a malignant disease prior to an incidence of an LMS of the thyroid[15,25]. While ultrasound, computed tomography scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are all useful in diagnosing a thyroid tumor, an immunohistochemical analysis is needed to confirm the diagnosis of a LMS. At the time of this review, an LMS of the thyroid has a poor survivability prognosis[19]. Herein, a new case of LMS conjoined with prior endometrial adenocarcinoma is described, which includes a comprehensive review of the literature about thyroid LMS.

A 60-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital complaining of pressure in her chest and neck as well as periodic dysphonia and breathing disorder.

Patient’s symptoms started a month ago with worsening in the past 24 h.

The patient’s past medical history included hypertension and a total hysterectomy that revealed an endometrial adenocarcinoma of the uterus. The adenocarcinoma was treated by means of radiotherapy using a micro-selectron application with a vaginal applicator, in which the total dose was 24 Gy in four cycles after surgery. This had been 5 years prior to the diagnosis of LMS.

The patient’s brother had also had a lung carcinoma.

Thyroid gland was enlarged, with palpable node in right lobe around 2 cm. The patient’s temperature was 36.4°C, heart rate was 80 bpm, respiratory rate was 22 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 145/80 mmHg, and oxygen saturation in room air was 90%.

The plasma level of the thyroid stimulating hormone, free thyroxine, free triiodothyronine, calcitonin, and carcinoembryonic antigen were within normal parameters.

An ultrasound of the neck dating from March 2016 indicated an enlarged thyroid, where the right lobe was 54 mm × 40 mm and its hypoechogenic nodule was 23 mm × 26 mm and calcified on its edges. The left lobe was 55 mm × 25 mm in size in which there were two micro-nodules of 6 mm × 5 mm and 7 mm × 5 mm that had no calcification. No computed tomography or MRI of the thyroid had been done prior to surgical treatment.

On July 20, 2016, the patient underwent a total thyroidectomy. There were no local or distant metastases detected, but the patient was found to have multiple enlarged lymph nodes (10 mm on the right and 11 mm on the left edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle).

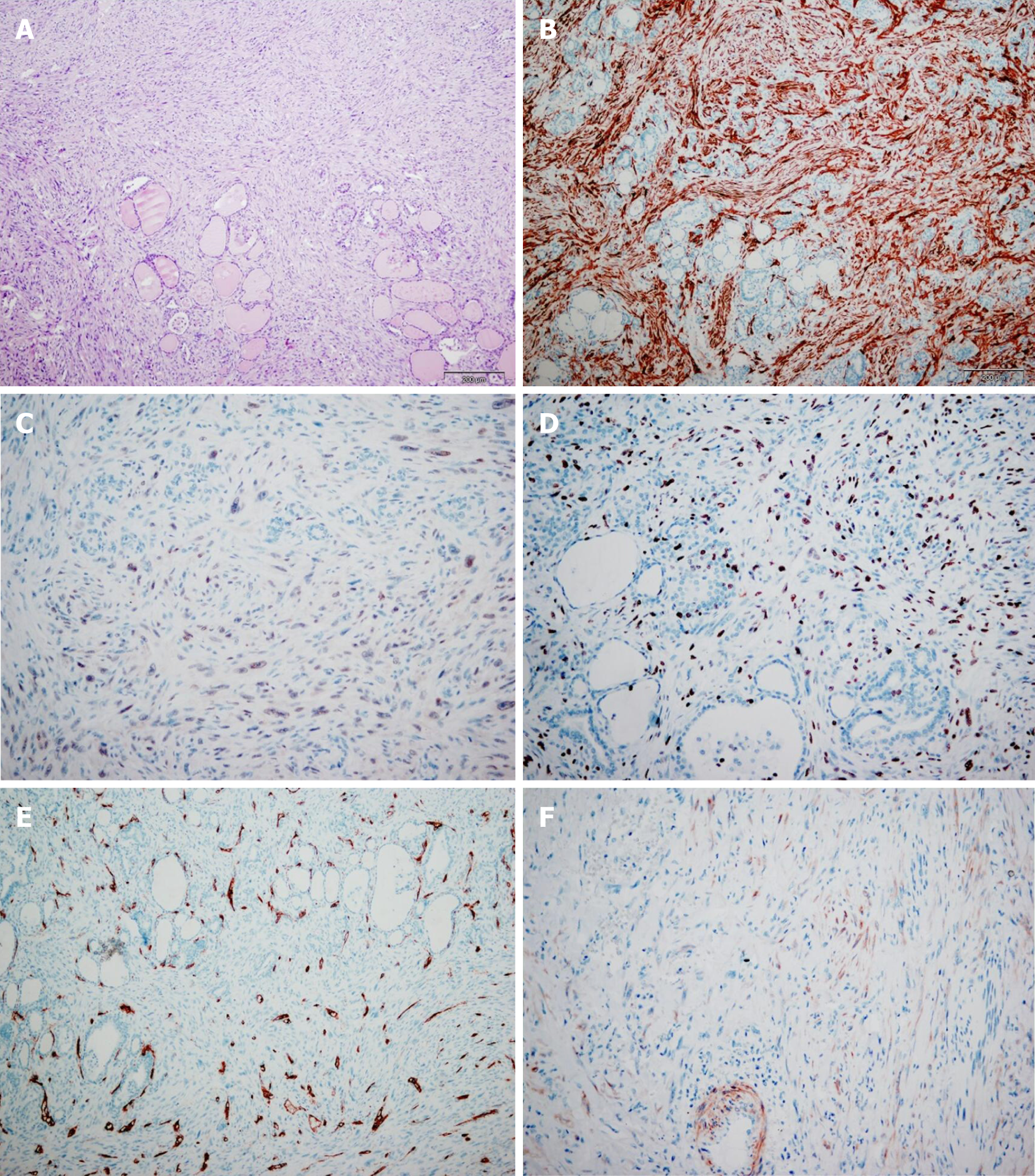

Pathological findings: Tissue specimens were fixed in a 10% formaldehyde solution, embedded in paraffin, cut into 4 μm thick sections and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Immunohistochemical staining was carried out according to the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex method.

Immunohistochemical staining with α smooth muscle actin (SMA) (DAKO, Clone 1A4, 1:400), Calponin (Lab Vision, Clone EP798Y, 1:100), H-caldesmon (LabVision, Clone h-CALD, 1:300), CD34 (NOVOCASTRA, Clone L-END/10, 1:100), p53 (NOVOCASTRA, Clone DO-7, 1:50), Ki67 (DAKO, Clone MIB-1, 1:100), estrogen receptor (NOVOCASTRA, Clone 6F11, 1:100), progesterone receptor (NOVOCASTRA, Clone PGR 312, 1:100), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (DAKO , Clone CS.1-4, 1:100) were done manually according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Table 1).

| Marker | Clone | Source | Antigen retrieval | Dilutions | Visualization kit manufacturer |

| α SMA | 1A4 | DAKO | Microwave oven, citrate, pH 6 | 1:400 | DAKO, EnVision |

| Calponin | EP798Y | Lab Vision | Microwave oven, citrate, pH 6 | 1:100 | DAKO, EnVision |

| H-caldesmon | h-CALD | LabVision | Water bath, citrate, pH 6 | 1:300 | DAKO, EnVision |

| CD34 | L-END | NOVOCASTRA | Microwave oven, citrate, pH 6 | 1:100 | DAKO, EnVision |

| p53 | DO-7 | NOVOCASTRA | Microwave oven, citrate, pH 6 | 1:50 | DAKO, EnVision |

| Ki67 | MIB-1 | DAKO | Microwave oven, DAKO 1700, pH 6 | 1:100 | DAKO, EnVision |

| ER | 6F11 | NOVOCASTRA | Microwave oven, citrate, pH 6 | 1:100 | DAKO, EnVision |

| PR | PGR 312 | NOVOCASTRA | Microwave oven, citrate, pH 6 | 1:100 | DAKO, EnVision |

| EBV | CS.1-4 | DAKO | Microwave oven, DAKO 1700, pH 6 | 1:100 | DAKO, EnVision |

Upon gross examination of the total thyroidectomy specimen, the right lobe and left lobe were measured at 38 mm × 54 mm × 49 mm and 54 mm × 40 mm × 38 mm, respectively. The sectioning of the right lobe indicated a non-encapsulated tumor node, vaguely limited, whitish in color, and firm in its consistency. Its dimensions at a cross section were 23 mm × 20 mm. Histologically, the tumor tissue was composed of atypical spindle cells of irregular fascicular growth, containing large, hyperchromatic nuclei. In a number of tumor cells, the cytoplasm was eosinophilic. While mitoses were common (8-10 per high power field), no necrosis was found. The tumor had invaded the surrounding thyroid parenchyma, but tumor tissue itself was not detected as present in the left lobe of the thyroid gland.

Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells tested positive for alpha SMA, calponin, and H-caldesmon, but were negative for CD34, p53, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and EBV. In approximately 25% of all the tumor cells, the Ki67 proliferative index was positive (Figure 1).

LMS of the thyroid.

The case was presented to the oncological team for soft tissue malignant tumors and to the oncological team for malignant endocrine tumors. It was thereafter decided that the patient should continue treatment under 3D conformal radiotherapy at a total dose of 50 Gy/25 fractions. Although increased therapy in the local tumor region had been planned at a 10 Gy dose divided into 5 fractions, its subsequent level of toxicity (mucositis) prevented it from being carried out.

Seven months following the surgery (February 2017) as part of her reevaluation, metastatic changes were found in the lungs: Two deposits in the right, measuring 11 mm and 17 mm, and in the left there were three micro-nodular changes that were a maximal size of 6 mm. It was then decided that the patient should begin chemotherapy. The patient was treated with three cycles of Adriamycin + (3, 3-dimethyl-1-triazeno)-imidazole-4-carboxamide after which the metastatic changes were shown to be in regression. However, a pulmonary embolism was also detected as well as a thrombosis of the jugular vein and an infection of the soft tissue of the neck. For this reason, chemotherapy was continued according to the MonoAdria protocol. In August, since osteoblastic activity was detected in the sternum on a scintigraphy, it was decided to initiate palliative radiotherapy and bisphosphonates. In October 2017, a phlebothrombosis of the left popliteal vein was detected. In November 2017, a palliative tracheotomy was performed. As had been suspected, a local metastasis was found. A pathological fracture of the femur in which another metastasis was also detected resulted in an osteosynthesis being performed.

LMS are extremely rare making up only 0.014% of all thyroid tumors[3].The first of such cases were reported in 1969[4]. The etiology of LMS is yet unknown, but the current research-based opinion is that it develops from the smooth muscles of the veins in the thyroid gland. A possible association between infection by EBV and LMS has also been investigated, as the youngest reported case was in a 6-year-old child who suffered from congenital immunodeficiency and an EBV infection prior to LMS[11]. Two other cases have also been reported of prior malignancy. In the first, the patient had been diagnosed with prostate cancer 3 years prior to LMS, which was thereafter treated by a prostatectomy and an orchiectomy without accompanying radiotherapy[25]. The second patient was reported to have had colorectal cancer (29 years prior) as well as breast cancer and then underwent a tumorectomy and radiotherapy 4 years prior to the diagnosis of LMS[15]. Given the background of these two cases, the influence of radiation should not be excluded when considering the etiology of LMS.

LMS is found more frequently in females than in males at a ratio of 1.7:1 (Table 2). It is also more often in older patients. The patient age at diagnosis ranges from 32 to 90. Not including the aforementioned case of the 6-year-old child, the median age is 65.

| Ref. | Age | Sex | Initial symptoms | Tumor size in cm | ILMN | IDM | Therapy | Outcome |

| [4] | 74 | F | Mass ongoing for 4 mo, pain | 12 | + | + | CT | DWD, 1 mo |

| [5] | 82 | M | Mass for 1 mo, dysphonia | 5.5 | - | - | Lobectomy + ND | DWD 4 mo, RS |

| [6] | 54 | F | Mass | ? | ? | ? | Lobectomy | Alive, 15 mo, NED |

| [7] | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | ? | ? | Alive, 12 mo |

| [8] | 54 | F | No symptoms | 3.5 | ? | ? | Lobectomy | Alive, 15 mo, NED |

| [9] | 72 | F | Mass ongoing for 7 mo | 3 | - | - | Lobectomy + ND | DWD, 51 mo, MD |

| [3] | 64 | F | Mass | 7.5 | ? | + | Uncompleted surgery | DWD, 5 mo, MD |

| [3] | 45 | M | Mass ongoing for 1 mo | 9 | ? | + | Lobectomy, CT | Alive, 11 mo, MD |

| [3] | 68 | M | Mass, dysphonia | 1.9 | ? | + | Uncompleted surgery | DWD, 18 mo, MD |

| [3] | 83 | M | Rapid growing mass, dysphagia | 5.5 | ? | + | Surgery | DWD, 3 mo, MD |

| [10] | 58 | F | Mass | 5 | - | - | Total thyroidectomy + ND | Alive, 25 mo, NED |

| [11] | 6 | M | Mass | 5 | - | + | Tumorectomy | No follow up after 4 mo, MD |

| [12] | 90 | F | Breathing disorder and a mass growing for 1 mo | 8 | ? | ? | Partial tumorectomy + trachelectomy, | DWD, 2 mo, pneumonia |

| [13] | 66 | F | Mass rapidly growing for ? mo | 8.5 | - | ? | Thyroidectomy, laryngectomy | Alive 3 mo, MD, RS |

| [14] | 43 | M | Growing mass over 2 mo | 6 | - | + | Thyroidectomy + ND, CT | DWD 6 mo |

| [15] | 83 | F | Mass, pain in the arm | 6.7 | ? | - | Biopsy, palliative therapy | DWD 2 mo, RS |

| [16] | 63 | F | Mass, weight loss, dysphagia | 7 | ? | + | Total thyroidectomy | DWD, 5 mo |

| [17] | 65 | F | Mass, weight loss, cough | 8 | - | - | Total thyroidectomy + ND, CT | DWD 4 mo |

| [18] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [19] | 65 | M | Left arm pain | 9 | - | - | Total thyroidectomy, partial esophagetomy | Alive after 5 yr of follow up |

| [20] | 72 | F | Neck mass with accompanying skin fistulae | 8.5 | - | - | Lobectomy with mass excision | DWD, 2 mo |

| [21] | 64 | F | - | - | - | + | Total thyroidectomy | DWD, 3 mo |

| [22] | 56 | M | Neck mass dysphonia, dysphagia | 3 | - | - | Total thyroidectomy + ND | DWD, 8 mo |

| [23] | 39 | M | Weight loss, dysphagia | 2.5 | - | + | Biopsy + RT | DWD 3 mo |

| [23] | 72 | F | Mass, breathing disorder | ? | + | + | Trachelectomy + biopsy | DWD, 1.5 mo |

| [25] | 65 | F | Neck mass dysphonia | 8.3 | - | + | Total thyroidectomy + lymphadenectomy | ? |

| [25] | 83 | M | Neck mass, dysphonia | 13 | - | - | Lobectomy, partial trachelectomy, CT | DWD, 5 mo, MD |

| [26] | 32 | F | Neck mass | 5 | - | - | Lobectomy, RT + CT | ? |

| Our Case | 60 | F | Mass, dysphonia, breathing disorder | 2.5 | - | - | Total thyroidectomy, RT + CT | Alive 17 mo, MD, thrombosis |

The most common symptom is a growing mass on the neck (23 cases), which is commonly painless[3-5]. Symptoms include: Dysphonia[3,5,22,24,25], dysphagia[3,16,22,23], weight loss[16,17,23], breathing disorder[12,23], arm pain[15,19], and skin fistulae[20]. Tumor size varies from 1.9 cm to 13 cm (mean: 6.4 cm). At the moment of diagnosis, three total cases recorded lymph-node metastasis. As opposed to anaplastic carcinoma that are more likely to present in lymph node metastasis, LMS often presents in distant metastasis, matching the total of twelve distant metastasis cases recorded here[3-6].

Only two cases had no normal plasma level for thyroid stimulating hormone. The first of which was 0.084 mU/L (normal range, 0.35‑5.5 mU/L) and free thyroxine at 26.79 pmol/L (normal range: 10.42‑24.32 pmol/L)[25]. The second case’s levels were elevated at 4.14 IU/mL (normal range: 0.34–3.90 IU/mL)[13]. All patients scored within a normal level of calcitonin.

Albeit radiological examination is useful in discovering and detecting different thyroid tumors, it is of little assistance in defining carcinoma type. Ultrasound can often show a well or ill-defined hypoechogenic mass or cystic or calcified nodule[5,8-10]. Computed tomography scans most often are able to show a large mass containing necrotic areas that may be accompanied by calcifications well as a local invasion of LMS[3,9,10,13,15]. MRI may display an isointense mass on T1-weighted images and an intermediate signal mass on T2-weighted images as fair enhancement on gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images[13]. Such radiological findings are nonspecific in view of the findings on other thyroid tumors, but the MRI of two cases did manage to indicate as such[14,15]. Thyroid scans (scintigraphy) may establish a cold nodule or an enlarged gland in areas of increased and decreased uptake of radioactive iodine[3,4,8,15].

Cut surfaces can differ in color from white to gray, yellowish, brownish-white, or pink. The tumor consistency can vary from firm, hard, or rubbery. Areas often contain necrosis, hemorrhage, calcification, hyalinization, or myxoid changes. The tumor is frequently composed of pleomorphic eosinophilic spindle cells forming fascicles or bundles. This fact complicates it from being distinguished from other undifferentiated carcinoma of the thyroid, such as spindle-cell variants of medullary carcinoma and spindle cell tumors that are thymus-like in differentiation, as well as uncommon primary and metastatic tumors of the thyroid that are predominant in spindle cells. Tumor cells may have normal or hyperchromatic nuclei that may be blunt-ended or cigar shaped that include occasional to frequent mitotic activity. In spite of the need for genetic/molecular studies to distinguish these entities, immunohistochemistry still plays a crucial role in the diagnosis of LMS[18-21,25].

Tumor cells in LMS are immunohistochemically positive for vimentin and SMA and are variable positive for desmin (50%-100%), HHF35, and H-caldesmon. There were three cases that tested negative for desmin. Cytokeratin, thyroglobulin, calcitonin, protein S100, and chromogranins were never positive[3,5-7].

Undifferentiated (anaplastic) thyroid carcinoma might have different microscopic features including spindle cells, which may mimic LMS, fibrosarcoma, or histiocytoma. The clinical presentation of tumor behavior is similar to LMS although anaplastic tumors more often result in metastases in the lymph nodes. Despite the fact that epithelial type cells can often be found in undifferentiated carcinoma, identifying them proves difficult at times. Unlike LMS, the tumor cells in undifferentiated carcinoma frequently test positive for cytokeratins and p53, but epithelial markers can still show negatively in approximately 20% of all cases. Vimentin and desmin are positive in more than 50% while SMA is always negative[15,20,21,24,].

The spindle form of medullary carcinoma should always be considered in the differential diagnosis. It scores positive for calcitonin, thyroglobulin, synaptophysin, chromogranin, cytokeratins, CD56, and TTF. Vimentin is a variable positive while SMA is negative[15,20,21,24].

Solitary fibrous tumors are also composed of spindle cells. They often have the clinical presentation of a slow-growing neck tumor. They generally test positive for CD34, BCL2, CD99, and vimentin. Their variable positivity to smooth muscle markers is also noted[15,20,21,24].

Rare primary tumors such as malignant peripheral-nerve sheath tumors, follicular dendritic-cell sarcoma, and histiocytic sarcoma should always be considered in addition to metastatic tumors to the thyroid. An LMS of the uterus is the most common sarcoma metastasizing in the thyroid. Nonetheless, thyroid metastases of any sarcoma or carcinoma that has prominent spindle cells or sarcomatoid features should also be kept in mind when doing a differential diagnosis. A clinico-radiological correlation and application of the panel of antibodies may help in determining the site of the tumor origin.

Of the 25 patients who have known outcomes, 17 passed away. Of these, 15 died within 1 year from their initial diagnosis, one after 18 mo and one after 51 mo. The median survival time was 5 mo[3-7]. There is yet to be any consensus on how LMS should be treated. Surgery has been the primary solution. A lobectomy, total thyroidectomy, and neck dissection are available options. Some patients underwent chemotherapy and radiotherapy, but did not yield promising results. Interestingly, none of the three patients that have had long post-treatment survival underwent chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Day et al[14] reported a patient overexpressing c-kit who was treated with immunotherapy and imatinib-mesylate, but then passed away 3 mo later.

Primary LMS of the thyroid is rare and should be considered when the patient does present with a rapidly growing neck mass. Previous malignancy and radio/chemotherapy should also be taken into consideration as risk factors. The prognosis of the tumor is poor and extensive surgery is often advised.

Thanks to pewdiepie for providing good content while writing paper, subscribe to pewdiepie.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: Montenegro

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Mogulkoc R, Coskun A S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | DeLellis RA, Loyd RV, Heitz PU. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Endocrine Organs. World health Organization Classification of Tumours. 3rd ed. IARC Press, Lyon. 2004;49-135. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Goldblum JR, Folpe AV, Weiss SW, Enzinger FM. Enzinger and Weiss's soft tissue tumors. 9th ed. Mosby Elsevier, Philadelphia Hardcover. 2008;249-269. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Thompson LD, Wenig BM, Adair CF, Shmookler BM, Heffess CS. Primary smooth muscle tumors of the thyroid gland. Cancer. 1997;79:579-587. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Adachi M, Wellmann KF, Garcia R. Metastatic leiomyosarcoma in brain and heart. J Pathol. 1969;98:294-296. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kawahara E, Nakanishi I, Terahata S, Ikegaki S. Leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid gland. A case report with a comparative study of five cases of anaplastic carcinoma. Cancer. 1988;62:2558-2563. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Kawaguchi Y, Kanazawa M, Nakayama K, Urazumi K, Takeuchi S, Abe R. A case of leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid gland showing fatal outcome with rapid course. Nihon Rinshou Gekai Gakkai Zasshi (Jpn J ClinSurg). 1990;51:1217-1221. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kaur A, Jayaram G. Thyroid tumors: cytomorphology of medullary, clinically anaplastic, and miscellaneous thyroid neoplasms. Diagn Cytopathol. 1990;6:383-389. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chetty R, Clark SP, Dowling JP. Leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Pathology. 1993;25:203-205. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Iida Y, Katoh R, Yoshioka M, Oyama T, Kawaoi A. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid gland. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1993;43:71-75. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Ozaki O, Sugino K, Mimura T, Ito K, Tamai S, Hosoda Y. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid gland. Surg Today. 1997;27:177-180. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tulbah A, Al-Dayel F, Fawaz I, Rosai J. Epstein-Barr virus-associated leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid in a child with congenital immunodeficiency: a case report. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:473-476. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tsugawa K, Koyanagi N, Nakanishi K, Wada H, Tanoue K, Hashizume M, Sugimachi K. Leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid gland with rapid growth and tracheal obstruction: A partial thyroidectomy and tracheostomy using an ultrasonically activated scalpel can be safely performed with less bleeding. Eur J Med Res. 1999;4:483-487. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Takayama F, Takashima S, Matsuba H, Kobayashi S, Ito N, Sone S. MR imaging of primary leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid gland. Eur J Radiol. 2001;37:36-41. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Day AS, Lou PJ, Lin WC, Chou CC. Over-expression of c-kit in a primary leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid gland. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:705-708. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Just PA, Guillevin R, Capron F, Le Charpentier M, Le Naour G, Menegaux F, Leenhardt L, Simon JM, Hoang C. An unusual clinical presentation of a rare tumor of the thyroid gland: report on one case of leiomyosarcoma and review of literature. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2008;12:50-56. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mansouri H, Gaye M, Errihani H, Kettani F, Gueddari BE. Leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid gland. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:335-336. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang TS, Ocal IT, Oxley K, Sosa JA. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid gland. Thyroid. 2008;18:425-428. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Qin Q, Liang ZH, Li AH. [Thyroid leiomyosarcoma: report of one cases]. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2012;47:75-76. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Mouaqit O, Belkacem Z, Ifrine L, Mohsine R, Belkouchi A. A rare tumor of the thyroid gland: report on one case of leiomyosarcoma and review of literature. Updates Surg. 2014;66:165-167. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Amal B, El Fatemi H, Souaf I, Moumna K, Affaf A. A rare primary tumor of the thyroid gland: report a new case of leiomyosarcoma and literature review. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:36. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tanboon J, Keskool P. Leiomyosarcoma: a rare tumor of the thyroid. Endocr Pathol. 2013;24:136-143. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ege B, Leventoğlu S. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the thyroid. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;85:43-46. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Şahin Mİ, Vural A, Yüce İ, Çağlı S, Deniz K, Güney E. Thyroid leiomyosarcoma: presentation of two cases and review of the literature. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;82:715-721. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gupta AJ, Singh M, Rani P, Khurana N, Mishra A. Primary Sarcomas of Thyroid Gland-Series of Three Cases with Brief Review of Spindle Cell Lesions of Thyroid. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:ER01-ER04. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zou ZY, Ning N, Li SY, Li J, DU XH, Li R. Primary thyroid leiomyosarcoma: A case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3982-3986. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ayadi M, Gabsi A, Meddeb K, Mokrani A, Yahiaoui Y, Letaief F, Chraiet N, Rais H, Mezlini A. Primary leiomyosarcoma of thyroid gland: the youngest case. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;26:113. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ordóñez NG, El-Naggar AK, Hickey RC, Samaan NA. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Immunocytochemical study of 32 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;96:15-24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hurlimann J, Gardiol D, Scazziga B. Immunohistology of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. A study of 43 cases. Histopathology. 1987;11:567-580. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Miettinen M, Franssila KO. Variable expression of keratins and nearly uniform lack of thyroid transcription factor 1 in thyroid anaplastic carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1139-1145. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 89] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | LiVolsi VA, Brooks JJ, Arendash-Durand B. Anaplastic thyroid tumors. Immunohistology. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;87:434-442. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |