Published online Nov 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i22.3872

Peer-review started: July 12, 2019

First decision: September 9, 2019

Revised: September 19, 2019

Accepted: October 5, 2019

Article in press: October 5, 2019

Published online: November 26, 2019

Primary peritoneal cancer (PPC) patients with BRCA mutations have a good prognosis; however, for patients with BRCA mutations who are diagnosed with PPC after prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy (PSO), the prognosis is poor, and survival information is scarce.

We treated a 56-year-old woman with PPC after bilateral mastectomy, hysterectomy, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. This patient had primary drug resistance and died 12 mo after the diagnosis of PPC. The genetic test performed on this patient indicated the presence of a germline BRCA1 mutation. We searched the PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane databases and extracted studies of patients with BRCA mutations who developed PPC after PSO. After a detailed literature search, we found 30 cases, 7 of which had a history of breast cancer, 14 of which had no history of breast cancer, and 9 of which had an unknown history. The average age of PSO patients was 48.86 years old (range, 31-64 years). The average time interval between the diagnosis of PPC and preventive surgery was 61.03 mo (range, 12-292 mo). The 2-year survival rate for this patient population was 78.26% (18/23), the 3-year survival rate was 50.00% (9/18), and the 5-year survival rate was 6.25% (1/16).

Patients with BRCA mutations who are diagnosed with PPC after preventative surgery have a poor prognosis. Prevention measures and treatments for these patients need more attention.

Core tip: To the best of our knowledge, this is the first article to describe the survival and prognosis of primary peritoneal cancer (PPC) after prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy (PSO) in patients with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Previous studies have shown that PPC patients with BRCA mutations have better therapeutic outcomes and prognosis, but the patient we reported showed primary resistance to initial treatment and only survived for 12 mo. We found that the 3-year survival rate was 50.00% (9/18) and the 5-year survival rate was only 6.25% (1/16) for patients with PPC after PSO, which is different from our previous perceptions, and these results are surprising.

- Citation: Ma YN, Bu HL, Jin CJ, Wang X, Zhang YZ, Zhang H. Peritoneal cancer after bilateral mastectomy, hysterectomy, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with a poor prognosis: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(22): 3872-3880

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i22/3872.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i22.3872

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome is an autosomal dominant genetic disease[1], accounting for approximately 10%-15% of ovarian cancer cases and 5% of breast cancer cases[2]. It is estimated that 25% of HBOC syndrome cases are caused by mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2[3]. Women with BRCA1/2 mutations have an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer and are counseled to undergo prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy (PSO) to reduce the 85% risk of coelomic epithelial cancer and the 25% risk of breast cancer[4]. However, approximately 1.0%-1.7% of HBOC patients are considered to be at risk for primary peritoneal cancer (PPC) after PSO[5-8]. Although PPC patients with BRCA mutations have longer progression-free survival and overall survival compared with BRCA mutation noncarriers[9], the prognosis of PPC patients after PSO is still unclear.

In this article, we report a patient who developed PPC after bilateral mastectomy and PSO surgery. This patient presented with primary drug resistance and died 12 mo after the diagnosis. We summarize the treatment of patients with PPC after PSO surgery reported in the literature to analyze the prognosis of this group of patients.

In January 2018, a 56-year-old woman came to our hospital complaining of obvious abdominal distension, lower extremity edema, and difficulty breathing for three days.

She had received diuretic treatment in a local hospital for lower extremity edema 5 d ago, following which the symptoms of edema improved.

In 2000, the patient underwent modified radical mastectomy for unilateral breast cancer with mammary ductal carcinoma (cT1cN0M0). The woman re-underwent modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer in 2003 due to contralateral breast cancer. In 2008, the woman underwent hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy for multiple uterine fibroids and dysfunctional uterine bleeding at the age of 46.

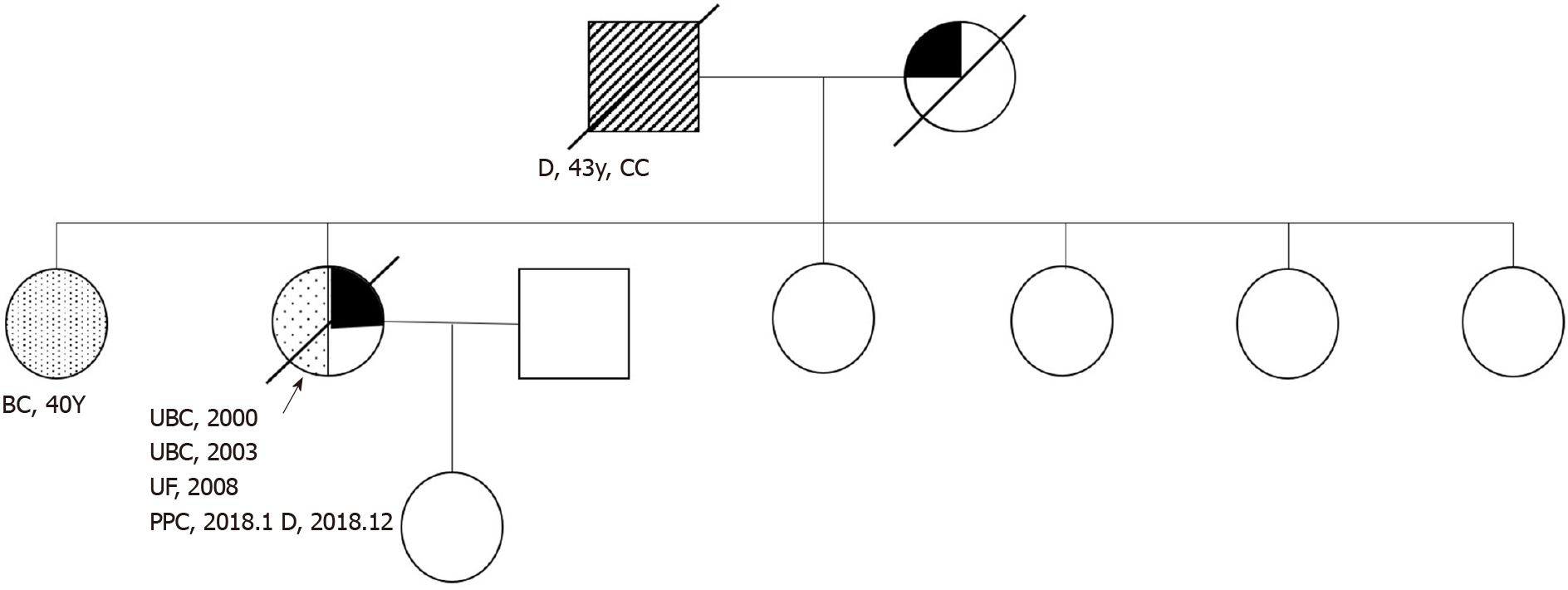

The patient had a history of hypertension for approximately 20 years, had blood pressures of up to 200/110 mmHg, and took oral Betaloc, Irbesartan, and Sulvastatin calcium tablets daily, with good blood pressure control achieved. The patient’s father died of cardiac cancer, and her mother died of coronary heart disease without a history of carcinoma. The patient had a total of 7 siblings, and the eldest sister had a history of double mastectomy for breast cancer. Figure 1 is a detailed family diagram for the patient.

We performed a careful physical examination and found that the patient’s bilateral groin areas had several swollen lymph nodes, and the largest one was approximately 1 cm × 2 cm. The patient had edema (++), which was nondepressed, was positive in the abdomen, and had no obvious tenderness or rebound tenderness. Bilateral breath sounds were reduced, and percussion of the chest showed dullness. No obvious abnormalities were found in the gynecological examination.

The preoperative serum level of cancer antigen (CA)-125 was 1634.00 U/mL.

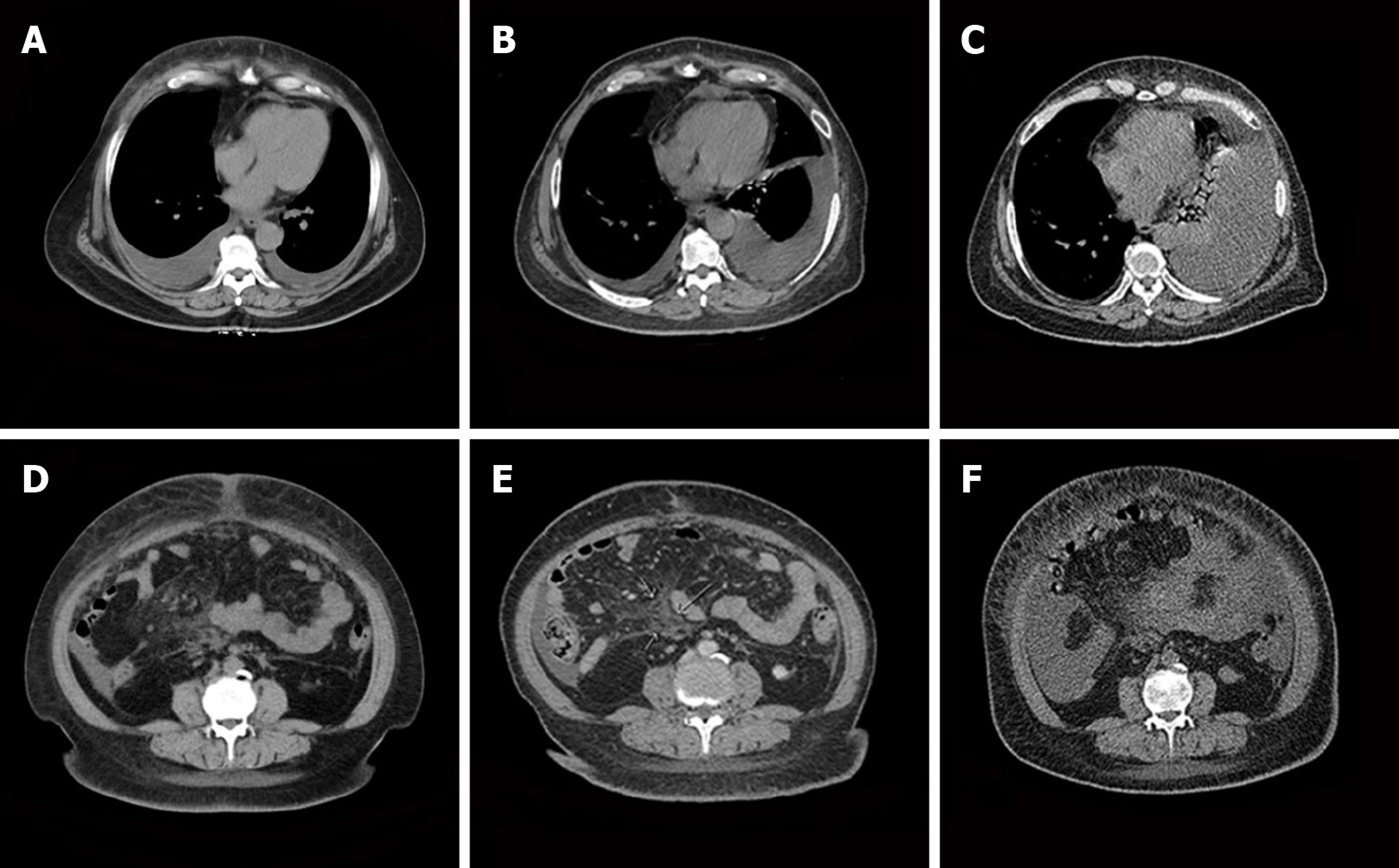

The patient’s abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan results on January 9, 2018 were as follows: (1) Bilateral pleural effusion, ascites, and subcutaneous edema of the chest and abdomen; (2) Mild pericardial thickening; (3) A small inflammatory lesion in the right lung; (4) Mediastinal and double inguinal lymphadenopathy; (5) Bilateral breast and uterus absence; and (6) Mild fatty liver. Gynecological ultrasound examination results on January 8, 2018 were as follows: (1) After hysterectomy; and (2) Pelvic and abdominal effusion.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was PPC.

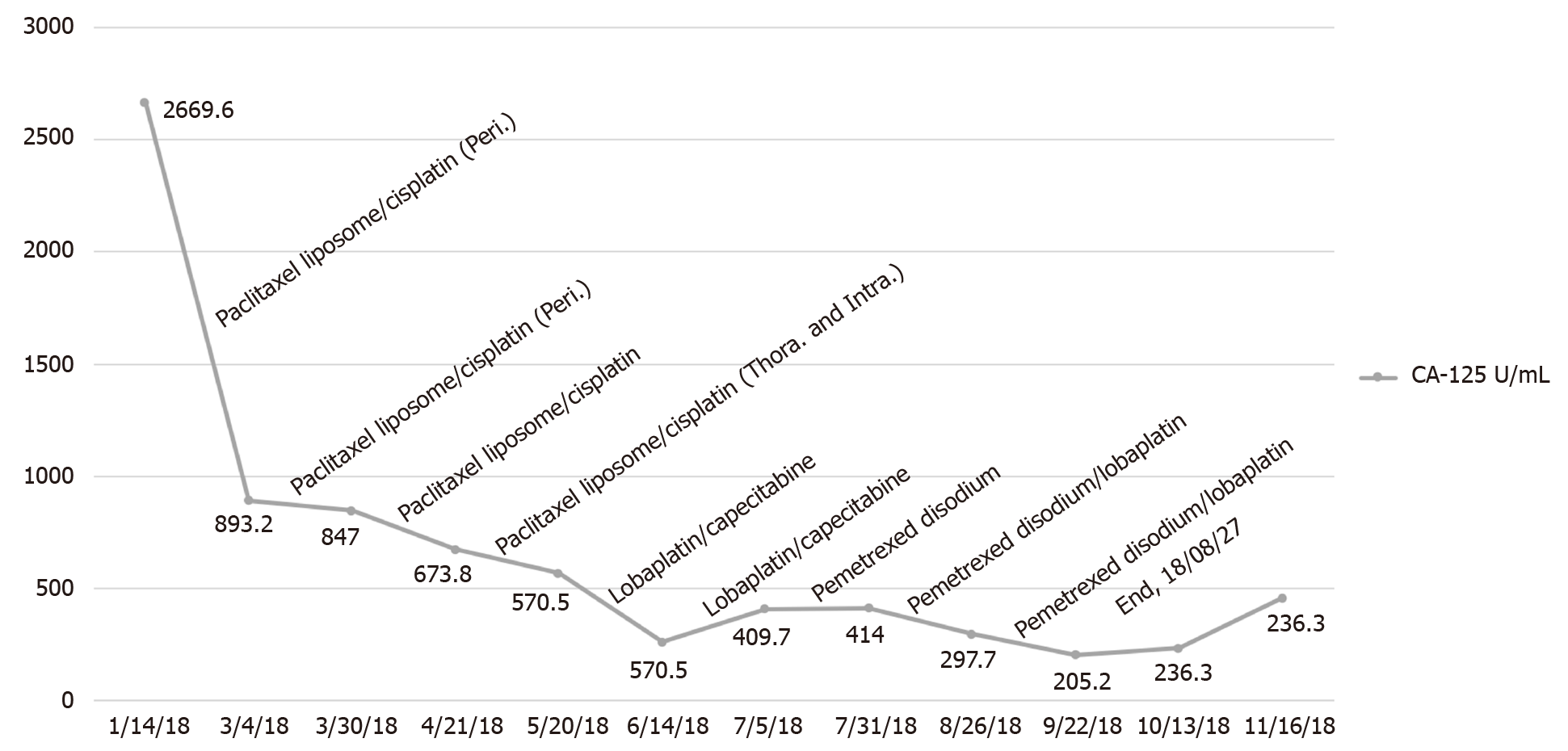

The patient underwent laparoscopic partial omentectomy on January 22, 2018. No obvious solid tumor lesions were found during the operation. The omentum was thickened with multiple miliary lesions and could not be completely removed due to the dense adhesion to the intestine. Postoperative pathology indicated high-grade serous adenocarcinoma. The postoperative chemotherapy regimen for this patient is given in Figure 2. During the treatment, we changed treatment programs because the pleural effusion and ascites increased repeatedly, as can be observed in Figure 3, and the chemotherapy ended on August 27, 2018. The germline BRCA testing is shown in Table 1. In addition, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification was used to detect all exons and adjacent splicing regions of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, and no abnormal copy number (large fragment deletion) was found.

| Gene | Mutation description | Mutation type | Mutant species | Clinical significance |

| BRCA1 | c.5085dupT (p.Val1696Cysfs*3) | Frameshift mutation | Heterozygous mutation | Pathogenic |

| BRCA2 | No pathogenic mutations detected | / | / | / |

Serum cancer antigen (CA)-125 levels did not fall to normal levels after surgery. The patient died 12 mo after diagnosis of the disease.

We searched the PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane databases and extracted studies of women with BRCA mutations who developed PPC after PSO and summarized their case information.

After a detailed literature search, we found 11 articles[4,5,7,10-17] that included patients with BRCA mutations who were diagnosed with PPC after PSO and had treatment information, and 30 cases that had survival information, as shown in Table 2. Of these 30 cases, 7 had a history of breast cancer, 14 had no history of breast cancer, and 9 had an unknown history. The average age of PSO was 48.86 years old (range, 31-64 years). The average time interval between diagnosis of PPC and preventive surgery was 61.03 mo (range, 12-292 mo). Among these women, there were 29 cases of BRCA1 mutation and only 1 case of BRCA2 mutation. The calculated 2-year survival rate was 78.26% (18/23), the 3-year survival rate was 50.00% (9/18), and the 5-year survival rate was 6.25% (1/16).

| Ref. | Age at PS (yr) | Previous breast cancer | Procedure | Interval between PS and PPC (mo) | Follow-up time (mo) | Status | BRCA1/2 mutation |

| Rebbeck et al[4] | N/A | NO | SO | 46 | N/A | N/A | BRCA1 |

| N/A | NO | SO | 103 | N/A | N/A | BRCA1 | |

| Casey et al[5] | 45 | NO | Hyst-BSO | 45 | 24 | DOD | BRCA1 |

| 38 | NO | Hyst-BSO | 67 | 24 | DOD | BRCA1 | |

| 48 | YES | Hyst-BSO | 21 | 11 | DOD | BRCA1 | |

| 44 | YES | Hyst-BSO | 13 | 48 | DOD | BRCA1 | |

| 31 | YES | BSO | 292 | 13 | DOD | BRCA1 | |

| Zakhour et al[7] | 39 | NO | BSO | 65 | 27 | DOD | BRCA1 |

| 47 | NO | BSO | 126 | 24 | Alive | BRCA1 | |

| 62 | YES | BSO | 19 | 24 | Alive | BRCA1 | |

| Olivier et al[10] | 60 | NO | SO | 27 | 22 | Alive | BRCA1 |

| 53 | NO | SO | 33 | 53 | DOD | BRCA1 | |

| 64 | NO | SO | 70 | 20 | Alive | BRCA1 | |

| Powell et al[11]1 | N/A | N/A | BSO | 84 | 12 | DOD | BRCA1 |

| N/A | N/A | BSO | 12 | 72 | DOD | BRCA1 | |

| N/A | N/A | BSO | 60 | 60 | Alive | BRCA1 | |

| Finch et al[12]1 | 46 | NO | Hyst-BSO | 36 | 36 | DOD | BRCA2 |

| 44 | YES | BSO | 12 | 48 | DOD | BRCA1 | |

| 38 | NO | BSO | 60 | 36 | DOD | BRCA1 | |

| 51 | YES | Hyst-BSO | 48 | 24 | Alive | BRCA1 | |

| 36 | NO | Hyst-BSO | 24 | 24 | Alive | BRCA1 | |

| 55 | YES | BSO | 24 | 24 | DOD | BRCA1 | |

| 51 | NO | BSO | 240 | 12 | Alive | BRCA1 | |

| Meeuwissen et al[13] | 61 | N/A | SO | 14 | 12 | DOD | BRCA1 |

| Rabban et al[14] | N/A | N/A | BSO | 62 | 24 | DOD | BRCA1 |

| N/A | N/A | BSO | 22 | 45 | Alive | BRCA1 | |

| Hill et al[15]1 | 56 | N/A | BSO | 60 | 36 | Alive | BRCA1 |

| Powell et al[16]1 | N/A | N/A | BSO | 60 | N/A | N/A | BRCA1 |

| N/A | N/A | BSO | 60 | N/A | N/A | BRCA1 | |

| Rhiem et al[17] | 57 | NO | BSO | 26 | 12 | Alive | BRCA1 |

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first article to describe the survival and prognosis of PPC after PSO in patients with HBOC. Previous studies have shown that patients with BRCA mutations have better therapeutic responses and prognosis, but the patient we reported showed primary resistance to the initial treatment and only survived for 12 mo. We calculated that the 3-year survival rate was 50.00% (9/18), and the five-year survival rate was only 6.25% (1/16), which was different from our previous notion, and these results are surprising.

HBOC syndrome is an autosomal dominant genetic disease. HBOC is the presence of both breast cancer and ovarian cancer in the same individual or male breast cancer, and HBOC patients are characterized by early-onset breast cancer, bilateral breast cancer and ovarian cancer, which can occur at any age. Among all ovarian cancer patients, 10%-15% are patients with HBOC syndrome[2].

The cumulative risk of ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, and PPC in BRCA1 mutation carriers is estimated to be 11% to 54% or higher, and the lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in BRCA2 mutation carriers is estimated to be between 11% and 27%[5]. There is strong evidence that for patients with HBOC syndrome, PSO significantly reduces the incidence of ovarian cancer by 81%-85%[4,18]. However, the protection is incomplete, the sine probability of developing PPC after PSO surgery is 1.0%-1.7%[5-8], and PSO may also result in surgical complications such as infections, blood clots, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risks, and even death. After PSO, artificial menopause may also lead to the occurrence of osteoporosis and the risks associated with it[19]. Some patients also need long-term hormone replacement therapy[20]. In terms of surgical methods, laparoscopic surgery is preferable to laparotomy, and the incidence of postoperative complications is 9%, of which 1%-2% are severe[21].

In 1982, Tobacman et al[22] first described cases of peritoneal cancer after prophylactic surgery. The study included 16 families, and at least two relatives in each family were diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Twenty-eight women in 16 families underwent prophylactic oophorectomy and were followed for 1-20 years. During that period, three people were diagnosed with PPC at 1 year, 5 years, and 11 years and died of disease progression 2 mo, 21 mo, and 12 mo after diagnosis. The authors did not analyze the three patients at the genetic level; however, they may carry BRCA mutations, which are consistent with the characteristics of HBOC. Finch et al[12]’s prospective study of 1045 patients estimated that the cumulative incidence of peritoneal cancer in BRCA mutation carriers was 4.3% within 20 years of PSO. Peritoneal cancer is more likely to occur in BRCA1 mutation carriers after PSO surgery, and it is very rare in BRCA2 mutation carriers. In the literature review we conducted, only one incidence of peritoneal cancer with BRCA2 mutation was found in a study by some researchers[5,7,10-12,14,17,18,22-26]. In the report by Finch et al[12], a woman with a BRCA2 mutation, who had no history of breast cancer, underwent prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and hysterectomy at age 46. She was then diagnosed with PPC when she was 49 years old, and she died of disease progression at the age of 52.

There are several hypotheses on the source of peritoneal cancer after surgery. The first one is that there may be residual oviduct tissue left during the PSO, leading to recurrence of ovarian cancer or fallopian tube cancer, and this theory emphasizes the need to completely remove the fallopian tubes. Preservation of the uterus during PSO may result in residual proximal tube, and the proximal end of the fallopian tube is more susceptible to carcinogenesis than the distal end; however, prevention of uterine resection during surgery seems unnecessary[17]. This hypothesis also explains the previous findings that the incidence of ovarian cancer in patients with BRCA mutations who have undergone tubal ligation has decreased[24,27,28]. Second, the specimens taken during the prevention of surgical resection are not comprehensive, and occult cancer is not found[5]; however, the clinically reported frequency of occult cancer found in PSO is 2%-17%[16,29-34]. Third, cancerous oviductal epithelial cells may flow into the abdominal cavity before resection during surgery and may lead to peritoneal cancer after many years[35]. The fourth hypothesis is that primary ovarian epithelial cancer, fallopian tube cancer, and PPC may originate from Mullerian hormones due to histological similarities between ovarian and peritoneal cancer[36].

There are higher progression-free survival and overall survival rates in ovarian cancer patients with BRCA mutations than in patients without[9]. The three-year survival rate of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers was 70% and 80%, respectively, and for the noncarriers, it was only 67%[37]. However, this survival advantage does not last more than 10 years after follow-up[38]. Unfortunately, the prognosis of HBOC patients with PPC who have undergone PSO is poor. Because of this, we reviewed a large number of documents and calculated the 3-year and 5-year survival rates of these patients; they were 50.00% and 6.25%, respectively, which gave us a new understanding of this disease.

Current research suggests that women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations should undergo prophylactic oophorectomy at age 35 or once they have finished bearing children[12,39]. However, there is still a lack of accurate and effective screening measures. Pelvic examination and transvaginal ultrasound are the standard methods for diagnosing ovarian tumors, but these are inadequate for screening because of their poor sensitivity. CA125 is a widely accepted serum biomarker for ovarian cancer, but it is a poor indicator in early-stage patients, with a sensitivity of approximately 40%[40]. In addition, due to the low incidence and atypical symptoms of peritoneal cancer, screening is more difficult.

Unfortunately, the postoperative treatment of the patient in this article did not include PARP inhibitors because the drugs were not available in China at that time; PARP inhibitors may have improved the survival of this patient.

In conclusion, approximately 1.0%-1.7% of carriers of BRCA1/2 mutations can develop PPC after PSO, and these patients are mainly BRCA1 mutation carriers. The treatment of this patient population is not effective, and the prognosis is very poor. There are no effective screening and preventive measures, and we should pay more attention to the diagnosis and treatment of this patient population. The conclusions we draw from this case report need to be confirmed by prospective studies.

We thank Hui Zhang for providing this case.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Daniilidis A S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Roy R, Chun J, Powell SN. BRCA1 and BRCA2: different roles in a common pathway of genome protection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;12:68-78. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 898] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 949] [Article Influence: 73.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Meaney-Delman D, Bellcross CA. Hereditary breast/ovarian cancer syndrome: a primer for obstetricians/gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2013;40:475-512. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kast K, Rhiem K, Wappenschmidt B, Hahnen E, Hauke J, Bluemcke B, Zarghooni V, Herold N, Ditsch N, Kiechle M, Braun M, Fischer C, Dikow N, Schott S, Rahner N, Niederacher D, Fehm T, Gehrig A, Mueller-Reible C, Arnold N, Maass N, Borck G, de Gregorio N, Scholz C, Auber B, Varon-Manteeva R, Speiser D, Horvath J, Lichey N, Wimberger P, Stark S, Faust U, Weber BH, Emons G, Zachariae S, Meindl A, Schmutzler RK, Engel C; German Consortium for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (GC-HBOC). Prevalence of BRCA1/2 germline mutations in 21 401 families with breast and ovarian cancer. J Med Genet. 2016;53:465-471. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 124] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rebbeck TR. Prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38 Suppl 6:S15-S17. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Casey MJ, Synder C, Bewtra C, Narod SA, Watson P, Lynch HT. Intra-abdominal carcinomatosis after prophylactic oophorectomy in women of hereditary breast ovarian cancer syndrome kindreds associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:457-467. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kauff ND, Satagopan JM, Robson ME, Scheuer L, Hensley M, Hudis CA, Ellis NA, Boyd J, Borgen PI, Barakat RR, Norton L, Castiel M, Nafa K, Offit K. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1609-1615. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 972] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 863] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zakhour M, Danovitch Y, Lester J, Rimel BJ, Walsh CS, Li AJ, Karlan BY, Cass I. Occult and subsequent cancer incidence following risk-reducing surgery in BRCA mutation carriers. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143:231-235. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dowdy SC, Stefanek M, Hartmann LC. Surgical risk reduction: prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and prophylactic mastectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1113-1123. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vencken PM, Reitsma W, Kriege M, Mourits MJ, de Bock GH, de Hullu JA, van Altena AM, Gaarenstroom KN, Vasen HF, Adank MA, Schmidt MK, van Beurden M, Zweemer RP, Rijcken F, Slangen BF, Burger CW, Seynaeve C. Outcome of BRCA1- compared with BRCA2-associated ovarian cancer: a nationwide study in the Netherlands. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2036-2042. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Olivier RI, van Beurden M, Lubsen MA, Rookus MA, Mooij TM, van de Vijver MJ, van't Veer LJ. Clinical outcome of prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers and events during follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1492-1497. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Powell CB, Chen LM, McLennan J, Crawford B, Zaloudek C, Rabban JT, Moore DH, Ziegler J. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) in BRCA mutation carriers: experience with a consecutive series of 111 patients using a standardized surgical-pathological protocol. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:846-851. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 126] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Finch A, Beiner M, Lubinski J, Lynch HT, Moller P, Rosen B, Murphy J, Ghadirian P, Friedman E, Foulkes WD, Kim-Sing C, Wagner T, Tung N, Couch F, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Ainsworth P, Daly M, Pasini B, Gershoni-Baruch R, Eng C, Olopade OI, McLennan J, Karlan B, Weitzel J, Sun P, Narod SA; Hereditary Ovarian Cancer Clinical Study Group. Salpingo-oophorectomy and the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation. JAMA. 2006;296:185-192. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 476] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 407] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Meeuwissen PA, Seynaeve C, Brekelmans CT, Meijers-Heijboer HJ, Klijn JG, Burger CW. Outcome of surveillance and prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy in asymptomatic women at high risk for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:476-482. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rabban JT, Krasik E, Chen LM, Powell CB, Crawford B, Zaloudek CJ. Multistep level sections to detect occult fallopian tube carcinoma in risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomies from women with BRCA mutations: implications for defining an optimal specimen dissection protocol. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1878-1885. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hill KA, Rosen B, Shaw P, Causer PA, Warner E. Incidental MRI detection of BRCA1-related solitary peritoneal carcinoma during breast screening--A case report. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:136-139. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Powell CB, Kenley E, Chen LM, Crawford B, McLennan J, Zaloudek C, Komaromy M, Beattie M, Ziegler J. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA mutation carriers: role of serial sectioning in the detection of occult malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:127-132. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 308] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rhiem K, Foth D, Wappenschmidt B, Gevensleben H, Büttner R, Ulrich U, Schmutzler RK. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:623-627. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Evans DG, Clayton R, Donnai P, Shenton A, Lalloo F. Risk-reducing surgery for ovarian cancer: outcomes in 300 surgeries suggest a low peritoneal primary risk. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:1381-1385. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Russo A, Calò V, Bruno L, Rizzo S, Bazan V, Di Fede G. Hereditary ovarian cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;69:28-44. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Lancet. 1997;350:1047-1059. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Reich H. Issues surrounding surgical menopause. Indications and procedures. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:297-306. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Tobacman JK, Greene MH, Tucker MA, Costa J, Kase R, Fraumeni JF. Intra-abdominal carcinomatosis after prophylactic oophorectomy in ovarian-cancer-prone families. Lancet. 1982;2:795-797. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Kauff ND, Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Robson ME, Lee J, Garber JE, Isaacs C, Evans DG, Lynch H, Eeles RA, Neuhausen SL, Daly MB, Matloff E, Blum JL, Sabbatini P, Barakat RR, Hudis C, Norton L, Offit K, Rebbeck TR. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy for the prevention of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated breast and gynecologic cancer: a multicenter, prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1331-1337. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 385] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rutter JL, Wacholder S, Chetrit A, Lubin F, Menczer J, Ebbers S, Tucker MA, Struewing JP, Hartge P. Gynecologic surgeries and risk of ovarian cancer in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 Ashkenazi founder mutations: an Israeli population-based case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1072-1078. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Reitsma W, de Bock GH, Oosterwijk JC, Bart J, Hollema H, Mourits MJ. Support of the 'fallopian tube hypothesis' in a prospective series of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy specimens. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:132-141. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Menkiszak J, Chudecka-Głaz A, Gronwald J, Cymbaluk-Płoska A, Celewicz A, Świniarska M, Wężowska M, Bedner R, Zielińska D, Tarnowska P, Jakubowicz J, Kojs Z. Prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 mutation carriers and postoperative incidence of peritoneal and breast cancers. J Ovarian Res. 2016;9:11. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Narod SA, Sun P, Ghadirian P, Lynch H, Isaacs C, Garber J, Weber B, Karlan B, Fishman D, Rosen B, Tung N, Neuhausen SL. Tubal ligation and risk of ovarian cancer in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations: a case-control study. Lancet. 2001;357:1467-1470. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Antoniou AC, Rookus M, Andrieu N, Brohet R, Chang-Claude J, Peock S, Cook M, Evans DG, Eeles R. EMBRACE, Nogues C, Faivre L, Gesta P. GENEPSO, van Leeuwen FE, Ausems MG, Osorio A; GEO-HEBON, Caldes T, Simard J, Lubinski J, Gerdes AM, Olah E, Fürhauser C, Olsson H, Arver B, Radice P, Easton DF, Goldgar DE. Reproductive and hormonal factors, and ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the International BRCA1/2 Carrier Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:601-610. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 117] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Colgan TJ, Murphy J, Cole DE, Narod S, Rosen B. Occult carcinoma in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens: prevalence and association with BRCA germline mutation status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1283-1289. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Kauff ND, Barakat RR. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in patients with germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2921-2927. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 114] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lu KH, Garber JE, Cramer DW, Welch WR, Niloff J, Schrag D, Berkowitz RS, Muto MG. Occult ovarian tumors in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations undergoing prophylactic oophorectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2728-2732. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 159] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Rabban JT, Crawford B, Chen LM, Powell CB, Zaloudek CJ. Transitional cell metaplasia of fallopian tube fimbriae: a potential mimic of early tubal carcinoma in risk reduction salpingo-oophorectomies from women With BRCA mutations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:111-119. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Callahan MJ, Crum CP, Medeiros F, Kindelberger DW, Elvin JA, Garber JE, Feltmate CM, Berkowitz RS, Muto MG. Primary fallopian tube malignancies in BRCA-positive women undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer risk reduction. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3985-3990. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 383] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Guillem JG, Wood WC, Moley JF, Berchuck A, Karlan BY, Mutch DG, Gagel RF, Weitzel J, Morrow M, Weber BL, Giardiello F, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Church J, Gruber S, Offit K. ASCO/SSO review of current role of risk-reducing surgery in common hereditary cancer syndromes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1296-1321. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Harmsen MG, Piek JMJ, Bulten J, Casey MJ, Rebbeck TR, Mourits MJ, Greene MH, Slangen BFM, van Beurden M, Massuger LFAG, Hoogerbrugge N, de Hullu JA. Peritoneal carcinomatosis after risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Cancer. 2018;124:952-959. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Iavazzo C, Gkegkes ID, Vrachnis N. Primary peritoneal cancer in BRCA carriers after prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2016;17:73-76. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kotsopoulos J, Rosen B, Fan I, Moody J, McLaughlin JR, Risch H, May T, Sun P, Narod SA. Ten-year survival after epithelial ovarian cancer is not associated with BRCA mutation status. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140:42-47. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Candido-dos-Reis FJ, Song H, Goode EL, Cunningham JM, Fridley BL, Larson MC, Alsop K, Dicks E, Harrington P, Ramus SJ, de Fazio A, Mitchell G, Fereday S, Bolton KL, Gourley C, Michie C, Karlan B, Lester J, Walsh C, Cass I, Olsson H, Gore M, Benitez JJ, Garcia MJ, Andrulis I, Mulligan AM, Glendon G, Blanco I, Lazaro C, Whittemore AS, McGuire V, Sieh W, Montagna M, Alducci E, Sadetzki S, Chetrit A, Kwong A, Kjaer SK, Jensen A, Høgdall E, Neuhausen S, Nussbaum R, Daly M, Greene MH, Mai PL, Loud JT, Moysich K, Toland AE, Lambrechts D, Ellis S, Frost D, Brenton JD, Tischkowitz M, Easton DF, Antoniou A, Chenevix-Trench G, Gayther SA, Bowtell D, Pharoah PD. for EMBRACE. kConFab Investigators. Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. Germline mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 and ten-year survival for women diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:652-657. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 125] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Rebbeck TR, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, Narod SA, Van't Veer L, Garber JE, Evans G, Isaacs C, Daly MB, Matloff E, Olopade OI, Weber BL; Prevention and Observation of Surgical End Points Study Group. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1616-1622. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1162] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 994] [Article Influence: 45.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Yokoi A, Matsuzaki J, Yamamoto Y, Yoneoka Y, Takahashi K, Shimizu H, Uehara T, Ishikawa M, Ikeda SI, Sonoda T, Kawauchi J, Takizawa S, Aoki Y, Niida S, Sakamoto H, Kato K, Kato T, Ochiya T. Integrated extracellular microRNA profiling for ovarian cancer screening. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4319. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 189] [Article Influence: 31.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |