Published online Jul 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i13.1717

Peer-review started: March 15, 2019

First decision: April 18, 2019

Revised: April 22, 2019

Accepted: May 2, 2019

Article in press: March 2, 2019

Published online: July 6, 2019

Benzbromarone is a uricosuric agent that reduces proximal tubular reabsorption of uric acid. Because of hepatotoxicity, it has been withdrawn from the market in Europe. Recently, some benefit-risk assessments of benzbromarone suggest that benzbromarone has greater benefits than risks, and the application of benzbromarone in the treatment of gout and hyperuricemia is still under debate.

A 39-year-old man was admitted to the hospital for icterus and nausea, and he was treated with benzbromarone (100 mg/d) for 4 mo because of hyperuricemia. He had a 10-year history of beer drinking (alcohol: about 28 g/d). Laboratory data showed severe liver injury and serious coagulation dysfunction; tests for autoimmune antibodies, viral hepatitis, and human immunodeficiency virus were negative. Despite administration of liver function-protecting drugs and efficient supportive treatment, the patient deteriorated quickly after hospitalization and developed grade II encephalopathy within a few days. The patient accepted continuous plasma exchange six times; however, his condition did not improve. Based on suggestions from multidisciplinary consultation, the patient underwent liver transplantation 26 d after admission. Liver specimen pathology results showed massive necrosis consistent with drug-induced liver injury, supporting the diagnosis of acute liver failure associated with benzbromarone. The patient recovered quickly thereafter.

This case highlights that clinicians should be on the alert for the severe hepatotoxicity of benzbromarone. Before prescribing benzbromarone, physicians should evaluate the high-risk factors that may lead to liver injury and provide suggestions for monitoring benzbromarone's hepatotoxicity during treatment.

Core tip: Here, we present a case of liver failure associated with benzbromarone. This is the ninth reported case associated with benzbromarone hepatotoxicity to date. We recommend that before prescribing, the benefits and risks of benzbromarone should be carefully evaluated. Additionally, an in-depth understanding of the relevant high-risk factors that may lead to liver injury and the prompt monitoring of hepatotoxicity of benzbromarone are essential.

- Citation: Zhang MY, Niu JQ, Wen XY, Jin QL. Liver failure associated with benzbromarone: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(13): 1717-1725

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i13/1717.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i13.1717

Benzbromarone is a uricosuric agent that reduces proximal tubular reabsorption of uric acid. Due to reports of severe hepatotoxicity, the use of benzbromarone has been pro-hibited in European and American countries[1]; however, the use of benz-bromarone is still allowed and frequently occurs in Asian countries[2]. In general, reports regarding its potentially severe hepatoxicity are rare. Here, we report a case of liver failure associated with the use of benzbromarone followed by a comprehensive literature review. The search strategy involved searching for the keywords “benzbromarone”, “liver injury”, and “liver failure” in various data-bases; 33 results were retrieved from PubMed and Web of Science (the dates were from the launch of the databases to December 30, 2018). A-dditionally, we used the terms “benz-bromarone”, “liver failure”, and “liver injury” in Chinese to search the China National Knowledge Infrastructure website, and three research studies (published between the launch of the database and December 30th, 2018) were retrieved. Further selection was performed by searching for reports that directly described the hepatotoxicity of benzbromarone, with eight studies selected (five in English, two in Chinese, and one in Japanese). In our literature review, we describe patient clinical features related to benzbromarone hepatotoxicity, combined with a benefit-risk assessment of benzbromarone. The results will provide additional evidence for evaluating the risk of selecting benzbromarone as a uricosuric drug and for mo-nitoring hepatotoxicity during treatment in clinical practice.

A 39-year-old man was admitted to the hospital for icterus and nausea on July 3, 2018.

Seven days before, he suffered from headache and vomiting and was deeply jaundiced.

Four months before admission, he started treatment with benzbromarone (100 mg/d) due to hyperuricemia, but he stopped taking the drug because of the recent jaundice. He had no history of liver disease or other diseases.

The patient has a history of drinking beer for 10 years and consumes approximately 28 g of alcohol per day. There was no family medical history of note.

Severe jaundice was found on the skin and sclera, and no signs of encephalopathy were found. The patient’s temperature was 36.8 °C, heart rate was 90 bpm, respiratory rate was 18 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 112/77 mmHg, and oxygen saturation was 98%. His body mass index was 23.7 kg/m2.

Laboratory indicators were as follows: Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 170.6 U/L; alanine transaminase (ALT), 208.2 U/L; γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT), 76 U/L; alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 94.2 U/L; total bilirubin, 702.5 µmol/L; direct bilirubin, 362.5 µmol/L; albumin, 34.2 g/L; prothrombin time, 33.5 s; prothrombin time activity, 25%. Tests for viral hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus were negative, and autoimmune antibody tests were negative. His blood ammonia level was 145 µmol/L (normal value: 9-47 µmol/L). Other laboratory data are provided in Table 1.

| Parameter | Result (normal value) | Parameter | Result (normal value) |

| AST (IU/L) | 170.6 (15-40) | WBC (×109/L) | 8.8 (3.5-9.5) |

| ALT (IU/L) | 208.2 (9-50) | RBC (×109/L) | 4.89 (4.3-5.8) |

| GGT (IU/L) | 76 (10-60) | Hemoglobin (g/L) | 152 (130-175) |

| ALP (IU/L) | 94.2 (45-125) | Platelets (×109/L) | 216 (125-350) |

| ACHE(IU/L) | 5050 (4300-12000) | Eosinophils (×109/L) | 0.1 (0.02-0.52) |

| TP (g/L) | 52.7 (65-85) | Basophils (×109/L) | 0.01 (0-0.06) |

| ALB (g/L) | 34.2 (40-55) | ||

| GLB (g/L) | 18.5 (20-40) | Coagulation function | |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 702.5 (6.8-30) | Prothrombin time (s) | 33.5 (9.0-13.0) |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 362.5 (0.0-8.6) | INR | 2.86 (0.80-1.20) |

| IBIL (μmol/L) | 340 (5.1-21.4) | PTA (%) | 25 (80-120) |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 1.64 (3.1-8) | ||

| CR (μmol/L) | 64 (57-97) | Virology test | |

| UA (μmol/L) | 178 (208-428) | Anti-HAV-IgM | - (-) |

| CHOL (mmol/L) | 3.52 (2.6-6.0) | Anti-HEV-IgM | - (-) |

| HBsAg | - (-) | ||

| Immunological test | HBeAg | - (-) | |

| Anti-dsDNA | - (-) | Anti-HBsAb | - (-) |

| Anti-gp210 | - (-) | Anti-HBeAb | - (-) |

| Anti-M2 | - (-) | Anti-HBcAb | + (-) |

| Anti-SSA-52/Ro52 | - (-) | Anti-HCV | - (-) |

| Anti-SP100 | - (-) | Anti-HIV | - (-) |

| Anti-Sm | - (-) | ||

| Anti-nRNP/Sm | - (-) | Tumor marker | |

| Immunoglobulin G4 | 0.545 (0.03-2.01) | α-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | 82.86 (< 20) |

| Immunoglobulin A | 3.01 (0.7-4.0) | Thyroid function | |

| Immunoglobulin G | 12.6 (7.0-16) | TSH (mIU/L) | 1.62 (0.372-4.94) |

| Immunoglobulin M | 0.86 (0.4-2.3) | FT3 (pmol/L) | 5.35 (3.1-6.8) |

| Complement (C3) | 0.58 (0.9-1.8) | FT4 (pmol/L) | 32.9 (12.0-22.0) |

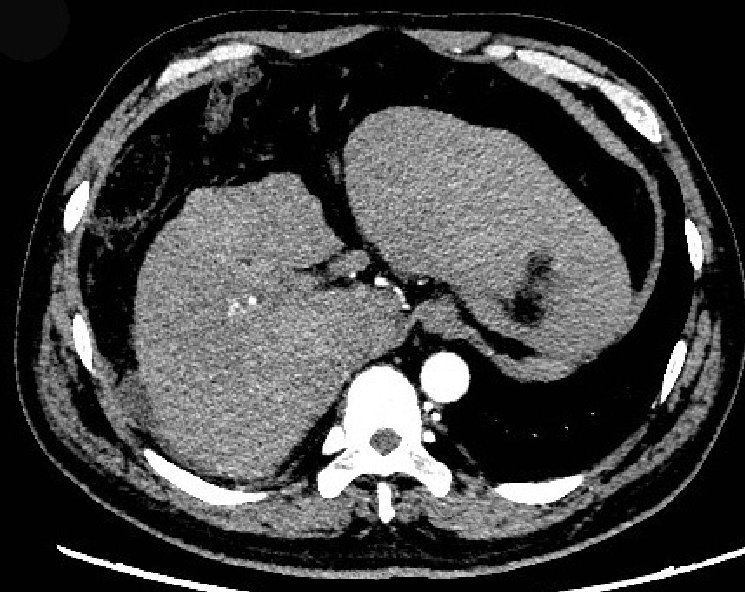

A computed tomography (CT) scan showed the following: The surface of the liver was irregular, the proportion of each part of the liver was not coordinated, the hilum and hepatic fissure were not wide, and the density of the liver parenchyma was slightly reduced; the intrahepatic bile duct was not dilated. Based on these findings, the patient was suspected of having liver cirrhosis (Figure 1).

The patient deteriorated quickly and developed grade II encephalopathy within a few days. We applied the RECUM criteria[3] to evaluate the possibility of drug-induced liver injury (DILI). The RECUM score of this patient was 9, which strongly indicated DILI, and the R value was 5.78, which indicated that this was a case of hepatocellular-type DILI.

Although there are reports about the hepatotoxicity of benzbromarone, severe liver failure due to this drug is rare, and the liver disease should be treated first. Treatment for gout should not be started under this condition.

The patient is young, and his condition became worse in a relatively short time.

If there is no sign of improvement, liver transplantation should be considered.

The patient should be registered for liver transplantation. Prior to the surgery, continuous plasma exchange (PE) with an artificial extracorporeal liver support system could be performed, and the best supporting treatment should be provided.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was acute liver failure due to benz-bromarone.

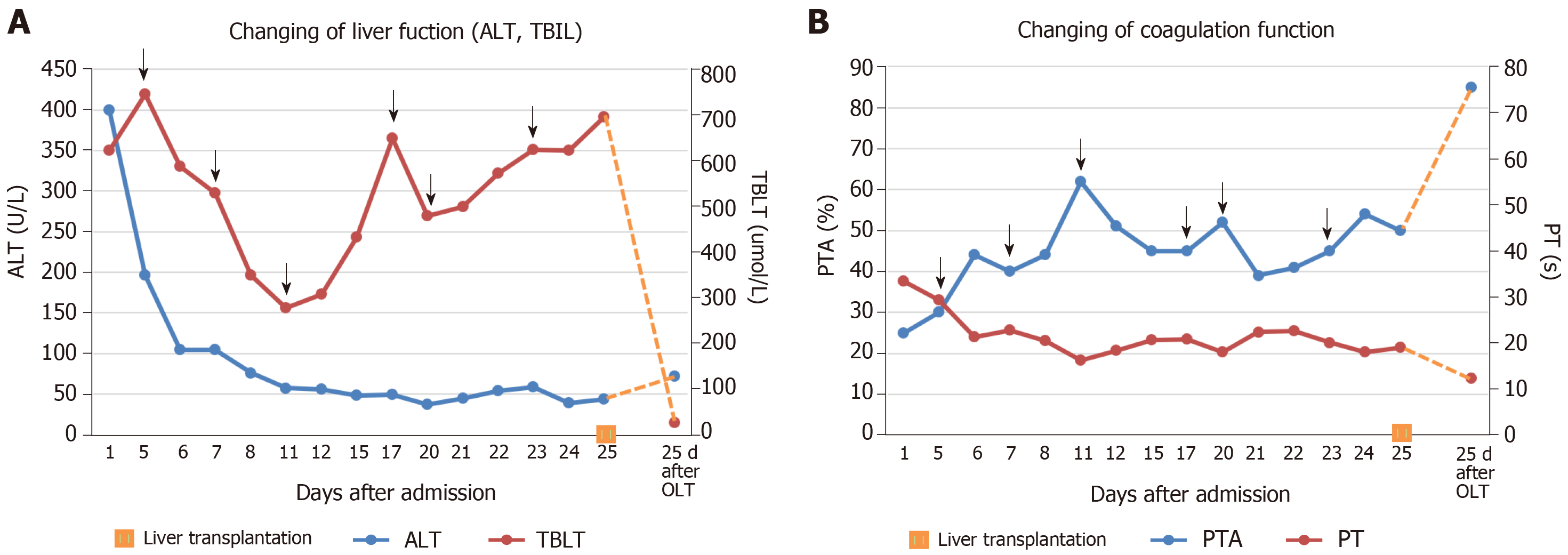

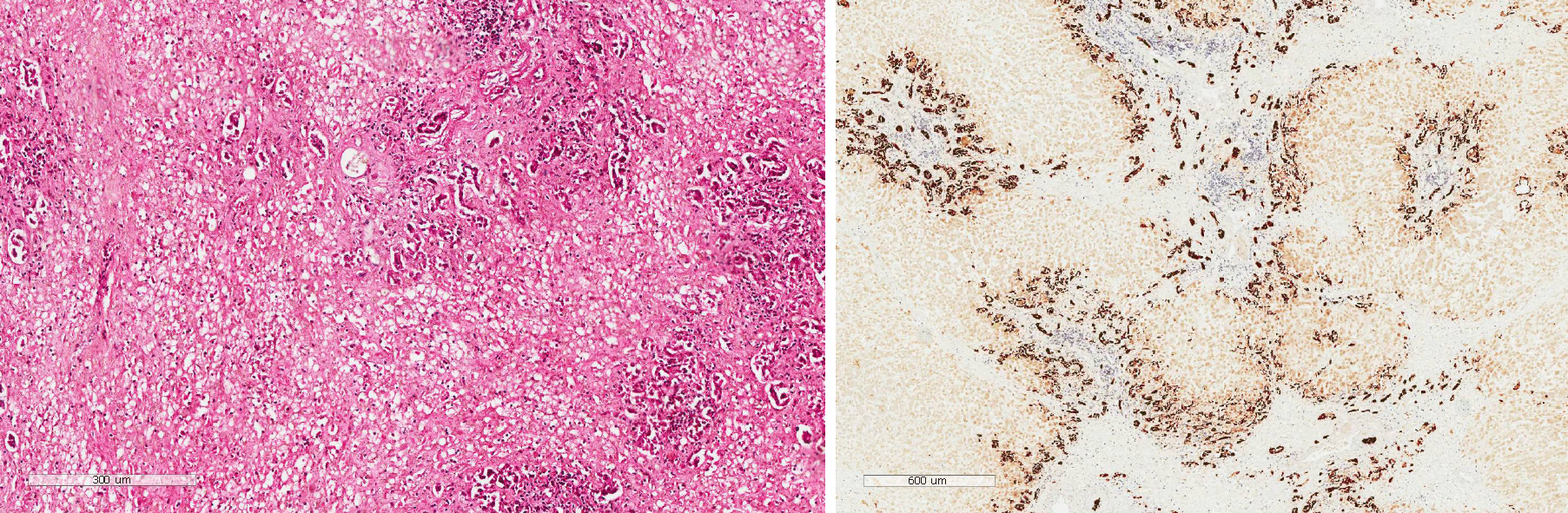

In addition to albumin and plasma infusion, adenosylmethionine and ornithine aspartate were administered to protect liver function. Additionally, ursodeoxycholic acid was provided orally, and continuous PE was performed six times. However, there was no improvement in the patient’s laboratory indices or clinical symptoms (Figure 2). The patient agreed to register for liver transplantation, and he underwent liver surgery 26 d after admission. Liver specimen pathology revealed massive necrosis of liver tissue, cholestasis, and biliary duct hyperplasia (Figure 3). When consulting with the pathology experts, they inferred that the change in the liver on the CT scan might be due to massive necrosis of liver tissue, which caused the shape of the liver to become irregular and atrophic. Liver cirrhosis was not diagnosed in this patient.

After liver transplantation, the patient recovered quickly, and jaundice and other symptoms, such as vomiting and headache, disappeared. Laboratory indicators were as follows: AST, 26.3 U/L; ALT, 72.2 U/L; GGT, 165.4 U/L; ALP, 77.2 U/L; total bilirubin, 25.9 µmol/L; direct bilirubin, 13.1 µmol/L; albumin, 31.8 g/L; prothrombin time, 12.4 s; prothrombin time activity, 85%. These indicators were markedly improved compared to the pre-transplantation levels. CT scanning showed a normal change after liver transplantation. The patient left the hospital 95 d after admission, on October 3, 2018, and remained well after 6 mo following transplantation.

The prevalence of gout in the general population is 1%-4%, and the annual incidence is 2.68 per 1000 persons. The worldwide incidence of gout has gradually increased due to poor dietary habits, such as the consumption of fast food, lack of exercise, and increased incidence of obesity and metabolic syndrome[4]. Gout has an important effect on musculoskeletal function and health-related quality of life. Poorly controlled gout leads to absence from work, health care use, and reduced social participation[5]. Previous clinical and pathophysiological data have shown that lowering uricemia to under the saturation point is the best and most reliable way to control gout symptoms in the long term. The most commonly used urate-lowering drugs are allopurinol, febuxostat, uricosurics, and urate oxidases. Benzbromarone is a powerful uricosuric drug; however, after reports of several serious hepatotoxicities, benzbromarone was withdrawn by Sanofi in 2003. Nonetheless, it was still recommended in clinical guidelines for patients with mild/moderate renal impairment[5,6]. Currently, benzbromarone is mainly used in Japan, China, Singapore, and other Asian countries. In China, benzbromarone is mainly used for the treatment of gout and hyperuricemia in clinical practice[7]. Thus far, most published hepatotoxicity cases due to benzbromarone have been reported in Asian countries (Figure 4).

The hepatotoxicity associated with benzbromarone might be explained by mitochondrial toxicity and subsequent induction of apoptosis and necrosis. Priska found that benzbromarone decreased the mitochondrial membrane potential of isolated rat hepatocytes by 81%. In mitochondria, benzbromarone decreased the state 3 oxidation and respiratory control ratios of L-glutamate, decreased mitochondrial β-oxidation, and increased reactive oxygen species production[8]. Another study demonstrated that benzbromarone is associated with profound changes in mitochondrial structure, which may be associated with apoptosis[9]. Additionally, Wang et al[10] reported that metabolic epoxidation is a key step in the development of benzbromarone-induced hepatotoxicity.

Hepatotoxicity is often associated with cytochrome P450-mediated bioactivation. Early metabolic studies revealed two major hydroxylated metabolites of benz-bromarone, 1’-hydroxy benzbromarone and 6-hydroxy benzbromarone, in urine, bile, and plasma[11]. Further oxidation of 6-hydroxy benzbromarone in human liver microsomes results in the formation of 5,6-dihydroxy metabolites[12]. These metabolites of benzbromarone have been reported to induce a transition in mitochondrial membrane permeability, and the metabolites and their reactive intermediates have been associated with liver injury[13-15]. According to Kaoru’s research, CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 catalyze the formation of 1’-hydroxy benzbromarone and 6-hydroxy benzbromarone, respectively, with CYP2C9 and CYP1A2 further catalyzing the formation of 5,6-dihydroxy benzbromarone in human liver microsomes. The activity of these CYP isozymes might be related to benzbromarone-induced liver toxicity[16].

We retrieved eight reported cases of benzbromarone-related hepatotoxicity, for a total of nine including the present case (Table 2): One from the Netherlands, one from Turkey, three from China, and the remaining four from Japan. In addition, the Periodic Safety Update Report listed 11 patients who developed hepatotoxicity from benzbromarone, among whom nine died; however, details of these unpublished data could not be obtained[17]. According to the National Center for Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) monitoring website, 533 side effects related to benzbromarone were reported in China before January 10, 2015, including 28 cases of liver injury (5.25%), 16 cases of mild liver injury (ALT abnormality, 1 × ULN < total bilirubin ≤ 5 × ULN, and no or mild symptoms), three cases of severe liver injury (ALT ≥ 10 × ULN, 5 × ULN < total bilirubin ≤ 10 × ULN, with severe symptoms and typical signs in physical examination), and nine cases that could not be clearly classified. No liver failure cases were reported on this website, and no more information was provided regarding these patients[7]. To date, the case presented here is the first report of liver failure related to benzbromarone in China.

| Age | Sex | Course of benzbro-marone | Dose | Combined medication | Prior liver diseases | Other diseases | Treatment | Outcome | Ref. |

| 68 | F | 3.5 mo | 200 mg/d (6 wk); 100 mg/d (2 mo) | Methyldopa | - | Gout, hypertension | Conservative treatment | Recovery (24 d) | [17] |

| 62 | M | 6 mo | 75 mg/d | - | - | Hyperurice-mia | Bilirubin absorption | Death(62 d) | [18] |

| 58 | M | 2 mo | Not described | Allopurinol, tocopherol, nicotinate, alprazolam, theophylline, azelastine hydrochloride, nilvadipine alcohol: (approximately 36 g/d) | - | Hyperurice-mia, hypertension, asthmatic bronchitis | PE + HDF, prednisolone (30 mg/d orally, reduced gradually) | Recovery (94 d) | [19] |

| 53 | F | 2 mo | 100 mg/d | Allopurinol | - | Hyperurice-mia, proteinuria | Liver transplant | Death (124 d) | [20] |

| 53 | M | 3 d | 50 mg/d | - | - | Hyperurice-mia, diabetes | Conservative treatment | Recovery (3 d) | [21] |

| 77 | F | 4 mo | Not described | Torsemide, nebivolol, ramipril, thyronajod | - | Hypertension, hyperthyroid disease, adiposity | Conservative treatment | Death (53 d) | [22] |

| 59 | M | More than 1 yr | 50 mg/d | Benidipine, pravastatin, alcohol (60 g/ d) | Liver dysfunction | Hyperurice-mia, hypertension, dyslipidemia | HDF, liver transplant | Recovery (70 d) | [23] |

| 47 | M | 15 d | Not described | Thiopronin | NAFLD | Gout, diabetes, hyperlipide-mia | Methylprednisolone (8 mg/d orally) | Recovery (70 d) | [24] |

| 39 | M | 4 mo | 100 mg/d | Alcohol: (approximately 28 g/d for 10 yr) | - | Gout | PE + liver transplant | Recovery |

Treatment in our case was successful. Based on suggestions from multidisciplinary consultation, the patient accepted the best supportive treatment, PE as bridge treatment, and liver transplantation, and the follow-up results were good. Our initial diagnosis was confirmed by pathological results of liver tissue sections. The limitation of this research was that we did not assess the activity of CYP isozymes, which might be related to benzbromarone-induced liver toxicity, as these tests were not available in our hospital.

Among all reported cases, four patients have died, three patients recovered after PE, hemodiafiltration, prednisolone, or liver transplantation, alone or in combination, and two patients took benzbromarone for less than 1 mo and recovered after conservative treatment or methylprednisolone therapy. Although benzbromarone hepatotoxicity varied in severity, a high proportion of patients developed acute liver failure, leading to death or emergency liver transplantation. Therefore, medical professionals should exert caution before prescribing this drug, and the risk of hepatotoxicity should be carefully assessed individually, as seven among nine reported patients used other drugs or alcohol when taking benzbromarone, which may aggravate damage to the liver.

Although benzbromarone has been withdrawn in Europe due to serious hepatotoxicity, there is still a debate regarding whether this is in the best interests of gout patients. In 2008, Lee et al[25] presented a benefit-risk assessment of benz-bromarone. These authors examined the clinical benefits associated with benzbromarone treatment and compared these benefits with alternative therapies, such as allopurinol and probenecid; they also examined the degree to which the reported cases of hepatotoxicity can be attributed to treatment with benzbromarone and calculated the incidence of benzbromarone hepatotoxicity in Europe (approximately 1/17000 patients). Based on this benefit-risk assessment, the authors recommended the use of benzbromarone for gout and suggested that the risks of hepatotoxicity could be ameliorated by employing a graded dosage increase and regular monitoring of liver function. CYP2C9 status determination and the consideration of potential impacts of inhibition of this enzyme should also be considered[25].

In 2015, the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) also performed a benefit-risk assessment of benzbromarone and suggested that the drug has greater benefits than risks in the treatment of gout or hyperuricemia. To prevent hepatotoxicity, the CFDA recommends the following: (1) Benzbromarone treatment should start at a low dose, and during treatment, liver function should be tested regularly; combination with other hepatotoxicity drugs should be avoided; (2) Attention should be paid to the signs of liver injury, such as loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and jaundice; once these signs occur, medical advice should be provided in a timely manner; and (3) Arug manufacturers should strengthen ADR monitoring to ensure that product safety information is provided to the public, especially to doctors and patients[7].

In summary, benzbromarone may have benefits in the treatment of gout or hyperuricemia, which support its application. Although cases of severe hepatotoxicity are rare, they can be fatal. Here, we present a successful treatment approach for liver failure associated with benzbromarone. The experience was that the risk of hepatotoxicity should be carefully assessed individually and that hepatotoxicity of benzbromarone should be properly monitored during treatment.

We sincerely thank professor Mei-Shan Jin from the Department of Pathology, First Hospital of Jilin University, for kindly helping us with accurate differential diagnosis based on the liver biopsy pathology.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Garbuzenko DV, Pallav K, Singh S S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | National Institutes of Health. DRUG RECORD: Benzbromarone. Available from: https://livertox.nlm.nih.gov/Benzbromarone.htm. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Ragab G, Elshahaly M, Bardin T. Gout: An old disease in new perspective - A review. J Adv Res. 2017;8:495-511. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 246] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yu YC, Mao YM, Chen CW. Guidelines for the management of drug-induced liver injury. J Clin Hepatol. 2015;31:1752-69. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Zhang W, Doherty M. Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:649-662. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 663] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 700] [Article Influence: 77.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dalbeth N, Merriman TR, Stamp LK. Gout. Lancet. 2016;388:2039-2052. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 623] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 621] [Article Influence: 77.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, Pascual E, Barskova V, Conaghan P, Gerster J, Jacobs J, Leeb B, Lioté F, McCarthy G, Netter P, Nuki G, Perez-Ruiz F, Pignone A, Pimentão J, Punzi L, Roddy E, Uhlig T, Zimmermann-Gòrska I; EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1312-1324. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 863] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 748] [Article Influence: 41.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | National Center for ADR Monitoring. Adverse Drug Reactions Information Circular (Phase 65) Alert Benzbromarone's Risk of Liver Injury. Available from: http://www.cdr-adr.org.cn/xxtb_255/ypblfyxxtb/201501/t20150110_ 7960.html. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Kaufmann P, Török M, Hänni A, Roberts P, Gasser R, Krähenbühl S. Mechanisms of benzarone and benzbromarone-induced hepatic toxicity. Hepatology. 2005;41:925-935. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 138] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Felser A, Lindinger PW, Schnell D, Kratschmar DV, Odermatt A, Mies S, Jenö P, Krähenbühl S. Hepatocellular toxicity of benzbromarone: effects on mitochondrial function and structure. Toxicology. 2014;324:136-146. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang H, Peng Y, Zhang T, Lan Q, Zhao H, Wang W, Zhao Y, Wang X, Pang J, Wang S, Zheng J. Metabolic Epoxidation Is a Critical Step for the Development of Benzbromarone-Induced Hepatotoxicity. Drug Metab Dispos. 2017;45:1354-1363. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Broekhuysen J, Pacco M, Sion R, Demeulenaere L, Van Hee M. Metabolism of benzbromarone in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1972;4:125-130. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | McDonald MG, Rettie AE. Sequential metabolism and bioactivation of the hepatotoxin benzbromarone: formation of glutathione adducts from a catechol intermediate. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:1833-1842. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shirakawa M, Sekine S, Tanaka A, Horie T, Ito K. Metabolic activation of hepatotoxic drug (benzbromarone) induced mitochondrial membrane permeability transition. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;288:12-18. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yoshida M, Cho N, Akita H, Kobayashi K. Association of a reactive intermediate derived from 1',6-dihydroxy metabolite with benzbromarone-induced hepatotoxicity. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2017;31. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Cho N, Kobayashi K, Yoshida M, Kogure N, Takayama H, Chiba K. Identification of novel glutathione adducts of benzbromarone in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2017;32:46-52. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kobayashi K, Kajiwara E, Ishikawa M, Oka H, Chiba K. Identification of CYP isozymes involved in benzbromarone metabolism in human liver microsomes. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2012;33:466-473. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | van der Klauw MM, Houtman PM, Stricker BH, Spoelstra P. Hepatic injury caused by benzbromarone. J Hepatol. 1994;20:376-379. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wagayama H, Shiraki K, Sugimoto K, Fujikawa K, Shimizu A, Takase K, Nakano T, Tameda Y. Fatal fulminant hepatic failure associated with benzbromarone. J Hepatol. 2000;32:874. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Suzuki T, Suzuki T, Kimura M, Shinoda M, Fujita T, Miyake N, Yamamoto S, Tashiro K. [A case of fulminant hepatitis, possibly caused by benzbromarone]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2001;98:421-425. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Arai M, Yokosuka O, Fujiwara K, Kojima H, Kanda T, Hirasawa H, Saisho H. Fulminant hepatic failure associated with benzbromarone treatment: a case report. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:625-626. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hou GC, Sun XL. A case of acute liver injury caused by Benzbromarone. Linchuang Yiyao Shijian. 2009;18:471. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Haring B, Kudlich T, Rauthe S, Melcher R, Geier A. Benzbromarone: a double-edged sword that cuts the liver? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:119-121. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Haga Y, Yasui S, Kanda T, Hattori N, Wakamatsu T, Nakamura M, Sasaki R, Wu S, Nakamoto S, Arai M, Maruyama H, Ohtsuka M, Oda S, Miyazaki M, Yokosuka O. Successful Management of Acute Liver Failure Patients Waiting for Liver Transplantation by On-Line Hemodiafiltration with an Arteriovenous Fistula. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2016;10:139-145. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhu FY, Meng Q. A severe case of acute liver injury caused by Benzbromarone. Chinese Hepatology. 2017;22:973-974. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Lee MH, Graham GG, Williams KM, Day RO. A benefit-risk assessment of benzbromarone in the treatment of gout. Was its withdrawal from the market in the best interest of patients? Drug Saf. 2008;31:643-665. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 199] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |