Published online Aug 16, 2017. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i8.344

Peer-review started: December 27, 2016

First decision: January 14, 2017

Revised: April 21, 2017

Accepted: May 12, 2017

Article in press: May 15, 2017

Published online: August 16, 2017

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare condition mostly seen in children and adolescents. Eosinophilic granuloma (EG) is one of its three clinical entities and is considered as a benign osteolytic lesion. Many reports of patients with spine histiocytosis are well documented in the literature but it is not the case of atlantoaxial localization. We report here a new observation of atlantoaxial LCH in a 4-year-old boy revealed by persistent torticollis. He was successfully treated with systemic chemotherapy and surgery. Inter-body fusion packed by autologous iliac bone was performed with resolution of his symptoms. It is known that conservative treatment is usually sufficient and surgery should be reserved for major neurologic defects in spine EG. In atlantoaxial lesion, surgical treatment should be frequently considered.

Core tip: Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare condition mostly seen in children and adolescents. Eosinophilic granuloma is one of its three clinical entities and is considered as a benign osteolytic lesion. Many reports of patients with spine histiocytosis are well documented in the literature but it is not the case of atlantoaxial localization. We report here a new observation of atlantoaxial LCH in a 4-year-old boy revealed by persistent torticollis.

- Citation: Tfifha M, Gaha M, Mama N, Yacoubi MT, Abroug S, Jemni H. Atlanto-axial langerhans cell histiocytosis in a child presented as torticollis. World J Clin Cases 2017; 5(8): 344-348

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v5/i8/344.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i8.344

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is an uncommon disorder characterized by an abnormal accumulation of histiocytes[1]. It includes three clinical entities namely eosinophilic granuloma (EG), Hand-Schûller-Christian syndrome and Letter-Siwe disease[2]. It consists in various clinical manifestations from a single lytic bone lesion to multisystemic lesions with organ dysfunction[3]. EG is a benign osteolytic lesion that commonly affects the skeletal system in a unifocal or multifocal form[2]. Atlantoaxial involvement by LCH is very rare[4,5], especially in a very young child[2,6,7]. The localization makes it difficult to diagnose. Neural deficit in spinal EG can be observed representing a life threatening condition[2,6]. The management is still controversial. We present, herein an unusual and rare case of atlantoaxial LCH with infiltrative mass involving the dens of C2 resulting in torticollis as the first symptom lasting for 3 wk in a 4-year-old boy. EG is discussed and the literature is reviewed.

A 4-year-old boy without significant medical history was admitted for limited neck motion for 3 wk. The physical examination showed an irreducible torticollis with analgesic attitude of cervical spine. The active and passive mobilization of the neck was painful and no motor or sensory deficit was detected. The general condition of the patient was good, the clinical examination did not show a tumoral syndrome and the neurological examination as well as skin examination and laboratory tests were normal.

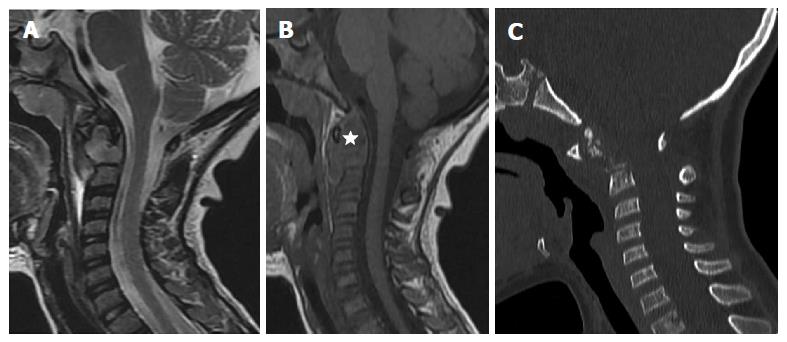

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of cerebro-spinal cord uncovered an infiltrative mass involving the dens of C2 which is hypointense on T1 sequence and hyperintense on T2 sequence, extending to the surrounding soft tissues leading to an increase in C1-C2 space, without compression of the spinal cervical cord. Complementary CT showed fragmented dens with important C1-C2 dislocation (Figure 1).

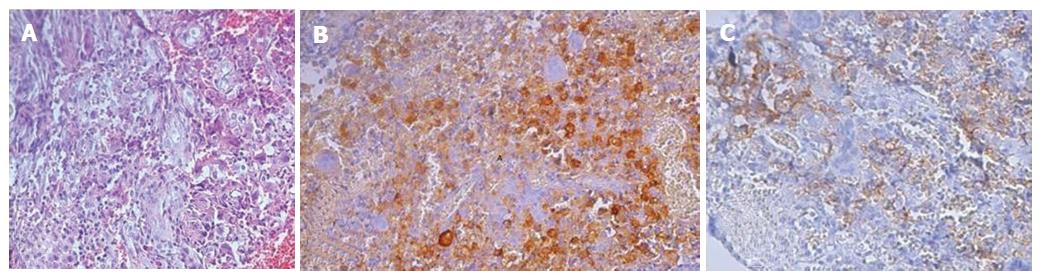

The odontoïd and mass biopsy was performed by endoscopic guidance. Histological features were consistent with inflammatory EG. The positivity of the immunostain by the antibody anti Ps100 and the antibody anti CD1a confirms the diagnosis of LCH (Figure 2).

Initial treatment was started prednisolone 40 mg/m2 per day orally, with weekly reduction starting from week 4 and intravenous Vinblastine 6 mg/m2 per week for six weeks. An external immobilization by a cervical collar was maintained during the entire period of chemotherapy.

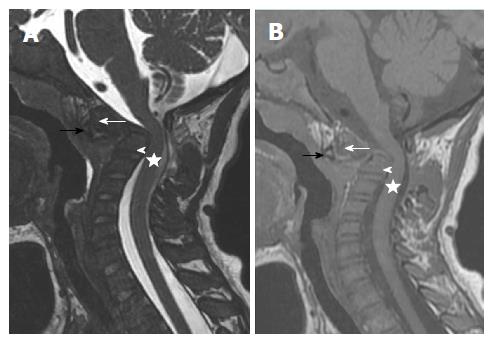

The evolution was marked by a decrease in pain secondary to the active mobilization of the neck with a persistent passive analgesic position. The control radiologic MRI showed a displaced horizontal fracture of the dens responsible for a posterior wall recoil reducing cervical occipital hinge without intramedullary signal abnormality. The infiltrative process had regressed in size (Figure 3).

A posterior cervical arthrodesis was performed and the spine was stabilized with a metal lacing associated with tricortical iliac crest graft interposed between the posterior arch of C1 and C2. No neuro-vascular complications have been detected.

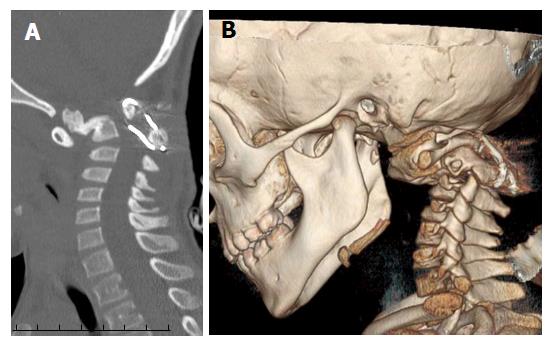

The patient is still under treatment consisting of prednisolone 40 mg/m2 per day orally for five days in a week every four weeks and IV Vinblastine 6 mg/m2 bolus every four weeks for 12 mo. Repeated CT scans revealed at 5 mo a consolidation of C2 fracture with moderate stenosis of the occipital hinge (Figure 4)

Spinal LCH commonly involves vertebral bodies, thoracic spine (54%) being the most common site of involvement followed by the lumbar (35%) and cervical spine (11%)[5]. Cervical vertebral involvement is exceedingly rare[6]. More than half of the cervical LCH lesions affect the C3-C5 vertebrae[4]. Atlantoaxial involvement by LCH is very rare[7]. Less than 15 cases have been reported in the literature. To our knowledge, it was the first Tunisian case of atlantoaxial LCH with odontoid process fracture reported in a 4-year-old child.

Our case present only torticollis as the first symptom, no other neurologic deficit was detected. In fact, pain, restricted range of motion or torticollis are the most common symptoms of cervical LCH[5]. However, the spinal destructive bony lesions etiology in children is extensive. Gaucher’s disease, osteogenesis imperfecta, aneurysmal bone cyst, myeloma, tuberculosis, Ewing’s sarcoma, osteogenic sarcoma, metastatic lesions, posterior fossa and cervical spinal cord tumors are part of the differential diagnosis of acquired torticollis with such bony lesions[5,7].

Loss of neural function is a rare occurrence with EG. It may result from vertebral collapse and impingement or, less frequently, from extradural extension of the lesion[5]. An asymptomatic case was also reported[2]. Since the atlantoaxial lesion was the only one detected in our case, the biopsy of the spine lesion under endoscopic guidance established the diagnosis. If there were multiple lesions, the most accessible lesion would be the appropriate for biopsy to avoid open biopsy and prevent the possible vertebral growth plate damage[6].

Our case fits into definitive diagnosis of LCH. The histological confirmation is required to establish LCH diagnosis[8]. The Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society identified three levels of confidence in the diagnosis of LCH. A definitive diagnosis, the third group, is established when histology is consistent with a diagnosis of LCH and the lesional cells are shown to express CD1a or to have intracytoplasmic Birbeck granules on electron microscopy[9]. Our patient presents a solitary spinal lesion. Spinal EG, in the literature, is frequently associated with multiple skeletal lesion[3]. It is recommended that a technetium bone scan or a skeletal survey be performed early in the evaluation of every child with a suspected spinal lesion[3,5].

Within the adult population, displaced type 2 odontoid process fracture can be treated operatively or non-operatively, depending on the patient age, co-morbidities, fracture pattern and displacement[2]. However, the management of such fractures in the pediatric population remains unclear especially in fracture spine due to LCH[10]. With such paucity of literature on this topic, it is unknown whether operative intervention associated with chemotherapy aid fracture union and functional outcome in young child.

In the present case, treatment consisted in chemotherapy (combination of oral prednisone and intravenous vinblastine). The effectiveness of this type of combination was demonstrated by LCH-I and LCH-II group in systemic LCH but the situation for spine EG remained unclear[1,9]. The infiltrative process has regressed in size with this association. The patient tolerated the treatment of chemotherapy with vinblastine well and showed no serious complications. The decision to continue treatment for one year was made.

Garg et al[3] report a spinal LCH in a child successfully treated without any chemotherapy use. The use of chemotherapy to treat solitary EG is still controversial, but it seems safe and effective in some studies. However, localized bone lesions with spontaneous regression are described[8]. The resolution occurred at a rate unaffected by the mode of treatment[6,8].

Despite the absence of the observed neurologic deficit, the young age of the patient and radiologic assessment with displaced horizontal fracture of the dens and compromised spinal stability conducted to surgical excision followed by auto-graft fusion with satisfactory outcome in the present case. The use of surgery in such case is still controversial[1,3,6].

Jiang et al[6] argue that mild neurologic deficit could be immobilized under strict observation and surgery should be reserved for major neurologic defects like myelopathy or monoparesis. The authors believe some intervention should be used to prevent possible LCH progress, especially in the C2 vertebral body. In this study, a protocol for the management of suspected LCH lesion of the cervical spine was suggested, the atlantoaxial LCH lesion is not included in this protocol[6].

The radiotherapy was discussed but not applied for our patient. Some bone LCH lesions can be treated by radiotherapy alone[10,11]. However, a non successful radiotherapy performed on a 15-year-old girl presenting C1/C2 lateral LCH mass was reported[6]. Moreover, some authors support that radiotherapy might destroy the potential growth of the endochondral plates[6]. Further research on this topic is recommended.

Atlantoaxial LCH is rare. The diagnosis of the disease was made within a brief time limit with torticollis as the only clinic symptom. A delay in the diagnosis of this disease may lead to progressive neurological deterioration and increasing compression affecting largely the prognosis. Treatment modalities have changed over time depending on the clinical severity of the disease since it is quite varied. The combination of chemotherapy and surgical procedure seems to be effective in such lesion. This hypothesis needs to be improved from each other experiences.

A 4-year-old boy without significant medical history was admitted for limited neck motion for 3 wk.

The physical examination showed an irreducible torticollis with analgesic attitude of cervical spine.

The spinal destructive bony lesions etiology in children is extensive. Gaucher’s disease, osteogenesis imperfecta, aneurysmal bone cyst, myeloma, tuberculosis, Ewing’s sarcoma, osteogenic sarcoma, metastatic lesions, posterior fossa and cervical spinal cord tumors are part of the differential diagnosis of acquired torticollis with such bony lesions.

Laboratory tests were normal.

The magnetic resonance imaging of cerebro-spinal cord uncovered an infiltrative mass involving the dens of C2 which is hypointense on T1 sequence and hyperintense on T2 sequence, extending to the surrounding soft tissues leading to an increase in C1-C2 space, without compression of the spinal cervical cord. Complementary CT showed fragmented dens with important C1-C2 dislocation.

The odontoïd and mass biopsy was performed by endoscopic guidance. Histological features were consistent with inflammatory eosinophilic granuloma (EG). The positivity of the immunostain by the antibody anti Ps100 and the antibody anti CD1a confirms the diagnosis of langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).

Initial treatment was started prednisolone 40 mg/m2 per day orally, with weekly reduction starting from week 4 and intravenous Vinblastine 6 mg/m2 per week for six weeks. An external immobilization by a cervical collar was maintained during the entire period of chemotherapy.

Atlantoaxial involvement by LCH is very rare. Less than 15 cases have been reported in the literature. To our knowledge, it was the first Tunisian case of atlantoaxial LCH with odontoid process fracture reported in a 4-year-old child.

LCH is an uncommon disorder characterized by an abnormal accumulation of histiocytes. It includes three clinical entities namely EG, Hand-Schûller-Christian syndrome and Letter-Siwe disease. It consists in various clinical manifestations from a single lytic bone lesion to multisystemic lesions with organ dysfunction.

Atlantoaxial LCH is rare. A delay in the diagnosis of this disease may lead to progressive neurological deterioration and increasing compression affecting largely the prognosis. Treatment modalities have changed over time depending on the clinical severity of the disease since it is quite varied. The combination of chemotherapy and surgical procedure seems to be effective in such lesion.

This is an interesting case report, which seems to provide readers with useful information. The manuscript is well written.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Tunisia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aviner S, Imashuku S S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang S

| 1. | Lewoczko KB, Rohman GT, LeSueur JR, Stocks RM, Thompson JW. Head and neck manifestations of langerhan’s cell histiocytosis in children: a 46-year experience. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78:1874-1876. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huang WD, Yang XH, Wu ZP, Huang Q, Xiao JR, Yang MS, Zhou ZH, Yan WJ, Song DW, Liu TL. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of spine: a comparative study of clinical, imaging features, and diagnosis in children, adolescents, and adults. Spine J. 2013;13:1108-1117. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Garg S, Mehta S, Dormans JP. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the spine in children. Long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1740-1750. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Howarth DM, Gilchrist GS, Mullan BP, Wiseman GA, Edmonson JH, Schomberg PJ. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: diagnosis, natural history, management, and outcome. Cancer. 1999;85:2278-2290. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Per H, Koç KR, Gümüş H, Canpolat M, Kumandaş S. Cervical eosinophilic granuloma and torticollis: a case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2008;35:389-392. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jiang L, Liu ZJ, Liu XG, Zhong WQ, Ma QJ, Wei F, Dang GT, Yuan HS. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the cervical spine: a single Chinese institution experience with thirty cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:E8-E15. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ha KY, Son IN, Kim YH, Yoo HH. Unstable pathological fracture of the odontoid process caused by Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37:E633-E637. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Vashisht D, Muralidharan CG, Sivasubramanian R, Gupta DK, Bharadwaj R, Sengupta P. Histiocytosis. Med J Armed Forces India. 2015;71:197-200. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Broadbent V, Gadner H, Komp DM, Ladisch S. Histiocytosis syndromes in children: II. Approach to the clinical and laboratory evaluation of children with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Clinical Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1989;17:492-495. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Kim W, O’Malley M, Kieser DC. Noninvasive management of an odontoid process fracture in a toddler: case report. Global Spine J. 2015;5:59-62. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Monsereenusorn C, Rodriguez-Galindo C. Clinical Characteristics and Treatment of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2015;29:853-873. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |