Published online Feb 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i5.980

Peer-review started: September 7, 2023

First decision: December 18, 2023

Revised: December 27, 2023

Accepted: January 18, 2024

Article in press: January 18, 2024

Published online: February 16, 2024

Processing time: 146 Days and 3.1 Hours

Microwave endometrial ablation (MEA) is a minimally invasive treatment method for heavy menstrual bleeding. However, additional treatment is often required after recurrence of uterine myomas treated with MEA. Additionally, because this treatment ablates the endometrium, it is not indicated for patients planning to become pregnant. To overcome these issues, we devised a method for ultrasound-guided microwave ablation of uterine myoma feeder vessels. We report three patients successfully treated for heavy menstrual bleeding, secondary to uterine myoma, using our novel method.

All patients had a favorable postoperative course, were discharged within 4 h, and experienced no complications. Further, no postoperative recurrence of heavy menstrual bleeding was noted. Our method also reduced the myoma’s maximum diameter.

This method does not ablate the endometrium, suggesting its potential appli

Core Tip: Ultrasound-guided microwave ablation of the uterine myoma does not ablate the uterine lining, suggesting the possibility of becoming a new treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding due to uterine fibroids for those who wish to conceive in the future.

- Citation: Kakinuma T, Kakinuma K, Okamoto R, Yanagida K, Ohwada M, Takeshima N. Abnormal uterine bleeding successfully treated via ultrasound-guided microwave ablation of uterine myoma lesions: Three case reports. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(5): 980-987

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i5/980.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i5.980

Uterine myomas [International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification system Type 0–7] are benign gynecological tumors commonly encountered in daily clinical practice; they cause abnormal uterine bleeding, especially heavy menstrual bleeding, menstrual pain, and other symptoms that impair the quality of life of women by interfering with their activities of daily living. In recent years, as conservative treatments for uterine myomas, uterine artery embolization (UAE) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) have been used and have demonstrated clinical efficacy. However, these treatment strategies cannot always achieve favorable outcomes and reduced complications as those achieved via surgical treatment, such as via hysterectomy[1,2]. Microwave endometrial ablation (MEA) is a method of protein coagulation using tissue dielectric heating produced by microwave irradiation to destroy the endometrium, including its basal layer, thereby reducing its function. As a result, it aims to reduce the amount of menstrual blood or induce amenorrhea. MEA is a minimally invasive treatment method that can be chosen to avoid heavy menstrual bleeding caused by systemic diseases, therapeutic drugs, and uterine myoma or adenomyosis uteri[3-5].

Our institution introduced this treatment method on January 2016 and has reported its efficacy[3]. Although MEA is expected to be effective in treating heavy menstrual bleeding caused by uterine myomas, numerous cases have been reported where supplementary treatment was required to manage postoperative recurrences of heavy menstrual bleeding[6,7]. In addition, because this treatment method ablates the endometrium, it is not indicated for patients planning for childbirth. Therefore, ultrasound-guided microwave ablation of feeding vessels of the uterine myomas was devised to overcome these issues.

We report the case of three patients who were successfully treated with ultrasound-guided microwave ablation of the vessels feeding the uterine myomas as a new novel treatment modality for heavy menstrual bleeding caused by uterine myomas.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the International University of Health and Welfare Hospital (approval number: 20-B-399, approval date: May 7, 2020).

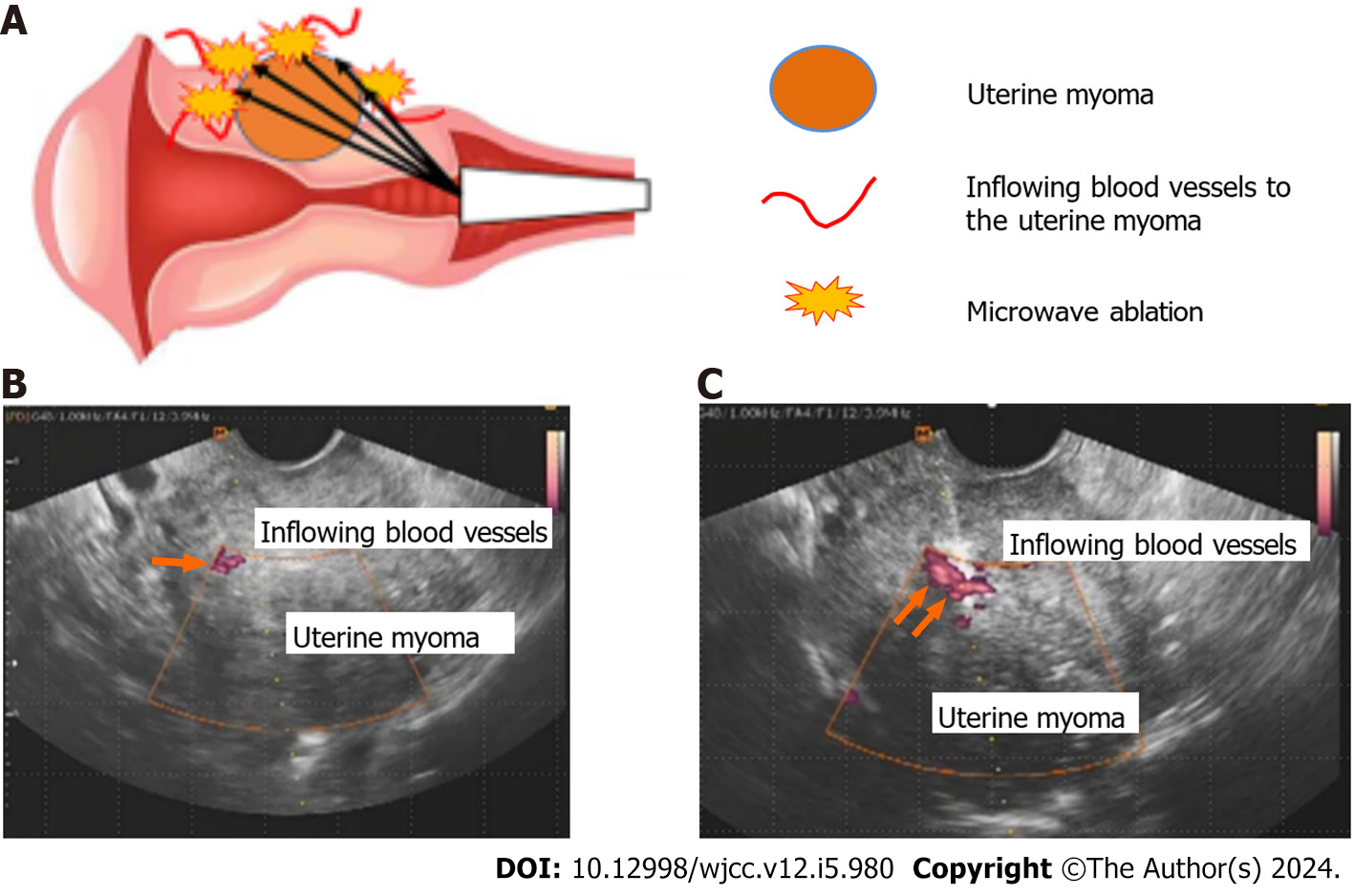

Ablation technique: The procedure for the ablation technique of transvaginal ultrasound-guided microwave ablation of uterine myoma lesions was initiated in the lithotomy position under intravenous anesthesia. This treatment was performed under transvaginal ultrasound guidance using the Microtaze AFM-712 and a CB-type CMD-16CBL-10/350 needle-shaped deep coagulation electrode (diameter, 1.6 mm) (both are products of Alfresa Pharma Corporation, Osaka, Japan). The schema for this procedure is shown in Figure 1A. Transvaginal ultrasound tomography using the color Doppler method was performed to identify the feeding vessels to the uterine myomas (Figure 1B). The feeding vessels were directly ablated with microwaves at 2.45 GHz using the needle-shaped deep coagulation electrode (Figure 1C). Each ablation was performed under the following conditions: five sets of Microtaze output of 30 W and an ablation duration of 10 s. All feeding vessels of the uterine myomas that could be identified were ablated. A visual analog scale (VAS) with a maximum score of 10 was used to grade menstrual blood loss and dysmenorrhea.

Cases 1-3: Heavy menstrual bleeding, dysmenorrhea.

Case 1: The patient had been experiencing heavy menstrual bleeding for 5 years; however, she had never consulted a gynecologist. At the age of 41 years, she was diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia, and treatment with dasatinib (tyrosine kinase inhibitor) was initiated. A decrease in platelets (17000/µL) and a worsening of heavy menstrual bleeding had been observed since the start of treatment. Massive genital bleeding was observed during the menstrual period, following which she visited our department.

Case 2: The patient had been experiencing heavy menstrual bleeding for 5 years, and it had been managed conservatively

Case 3: The patient had been experiencing heavy menstrual bleeding for 5 years and had been managed conservatively with hormone therapy (LNG-IUS) for one year. However, she was referred to our department for treatment owing to symptom exacerbation.

Case 1: Past medical history: Chronic myelogenous leukemia (age, 41 years).

Case 1: Pregnancy and delivery history: One pregnancy and one delivery (cesarean section at the age of 30 years).

Cases 2 and 3: Pregnancy and delivery history: Two pregnancies and two deliveries.

Cases 1-3: Cervical and endometrial cytology: Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy.

Cervical and endometrial cytology: Negative.

Case 1: Transvaginal ultrasound tomography findings: A mass of 65 mm in size was found in the anterior wall of the uterus (FIGO classification system Type 4). Pelvic MRI findings: T2-weighted sagittal image showed a mass of 65 mm in the maximum diameter in the anterior wall of the uterus with low signal intensity (Figure 2A).

Case 2: Transvaginal ultrasound tomography findings: A mass of 35 mm in the maximum diameter was found in the anterior wall of the uterus (FIGO classification system Type 4). There were no notable findings in the bilateral uterine appendages. Pelvic MRI findings: T2-weighted sagittal image showed a mass of 35 mm in the maximum diameter in the anterior wall of the uterus with low signal intensity (Figure 2B).

Case 3: Transvaginal ultrasound tomography findings: Masses of 22 mm and 15 mm in the maximum diameter were found in the anterior wall of the uterus (FIGO classification system Type 4 and 5). There were no notable findings in the bilateral uterine appendages. Pelvic MRI findings: T2-weighted sagittal image showed masses of 22 mm and 15 mm in the maximum diameter in the anterior wall of the uterus with low signal intensity (Figure 2C).

Based on the above findings, organic, drug-induced heavy menstrual bleeding was diagnosed (FIGO AUB system 2 AUB-Lo;-I).

Based on the above findings, a diagnosis of heavy menstrual bleeding caused by uterine myoma was established (FIGO AUB system 2, AUB-Lo).

Based on the above findings, a diagnosis of heavy menstrual bleeding caused by uterine myomas was established (FIGO AUB system 2, AUB-Lo).

Treatment course: Dasatinib administration was stopped, and red blood cell and platelet transfusions were performed. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided microwave ablation of the uterine myoma was planned to control heavy menstrual bleeding after obtaining adequate informed consent.

In the present case, five feeding vessels were identified in the vicinity of the uterine myoma, and this area was ablated. The procedure time was 45 minutes, and the amount of blood loss was minimal. The patient’s course was favorable, and she was discharged 4 h after the procedure and followed up on an outpatient basis.

Treatment course: Transvaginal ultrasound-guided microwave ablation of the uterine myoma was planned for the purpose of controlling heavy menstrual bleeding after obtaining adequate informed consent. Four feeding vessels were identified in the vicinity of the uterine myoma, and this area was ablated with microwaves at 2.45 GHz. The procedure time was 40 min, and the amount of blood loss was minimal. The patient's course was favorable, and she was discharged 4 h after the procedure and followed up on an outpatient basis.

Treatment course: Transvaginal ultrasound-guided microwave ablation of the uterine myomas was planned for the purpose of controlling after obtaining adequate informed consent. Six feeding vessels were identified in the vicinity of the uterine myomas, and this area was ablated with microwaves at 2.45 GHz. The procedure time was 53 min, and the amount of blood loss was minimal. The patient's course was favorable, and she was discharged 4 h after the procedure and followed up on an outpatient basis.

Postoperative course: Menstruation resumed 1 month after treatment, and VAS showed that clinical symptoms improved markedly (heavy menstrual bleeding from 10 preoperatively to 1 postoperatively and menstrual pain from 10 preoperatively to 2 postoperatively) and the Hb value showed a remarkable increase to 12.3 g/dL. In addition, the maximum diameter of the uterine myoma was reduced from 65 mm preoperatively to 27 mm at 3 months postoperatively (Figure 3A). No complications were observed during the course, and 36 months have passed since the procedure without recurrence of heavy menstrual bleeding. In addition, the patient resumed treatment for chronic myelogenous leukemia immediately after surgery.

Postoperative course: Menstruation resumed 1 month after treatment, and the VAS showed that clinical symptoms appeared to improve remarkably (both heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea from 10 preoperatively to 1 postoperatively) and the Hb value markedly increased to 13.2 g/dL. In addition, the maximum diameter of the uterine myoma was reduced from 35 mm preoperatively to 20 mm at 3 months postoperatively (Figure 3B). No complications were observed during the course, and 18 months have passed since the procedure without recurrence of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Postoperative course: Menstruation resumed 1 month after treatment, and the VAS showed that clinical symptoms improved markedly (both heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea from 10 preoperatively to 1 postoperatively) and the Hb value markedly increased to 13.2 g/dL. The maximum diameter of the uterine myomas was reduced from 22 mm and 15 mm preoperatively to 15 mm and 13 mm (Figure 3C). No complications were observed during the course, and 12 months have passed since the procedure without recurrence of heavy menstrual bleeding.

MEA is an ablation technique that uses 2.45 GHz microwave irradiation for endometrial ablation, including its basal layer. MEA has been reported to be useful as an alternative therapy to avoid total hysterectomy for heavy menstrual bleeding[3-5]. Although MEA is expected to be effective in treating uterine myomas, a small number of cases have been reported where additional treatment was required because of postoperative recurrence[6,7].

Therefore, we performed a microwave ablation of uterine myoma lesions as a new treatment attempt for heavy menstrual bleeding caused by uterine myomas. This treatment method identifies the feeding vessels to the uterine myoma using the color Doppler method before ablation and selectively ablates the feeding vessels with ultrasound-guided microwave ablation. This facilitates in reducing the procedure time by directly ablating the feeding vessels, even for relatively large myomas. In addition, we believe that microwave ablation of the feeding vessels to the uterine myomas not only improved clinical symptoms such as heavy menstrual bleeding and anemia but also reduced the size of the uterine myomas caused by decreased blood flow to the uterine myomas. Furthermore, we used a needle-shaped deep coagulation electrode to ablate the feeding vessels to the uterine myomas; these electrodes are thin as 1.6 mm in diameter and are considered effective for use in minimally invasive procedures. All patients were discharged within 4 h postoperatively and had no postoperative complications. In addition, menstruation resumed 1 month after the procedure; however, no recurrence of heavy menstrual bleeding or other symptoms was observed, confirming the efficacy and safety of the process.

As a conservative treatment for uterine myomas, UAE is available. This is an interventional radiology procedure for the transcatheter embolization uterine arteries or other vessels. Since Ravina from France reported this procedure in 1995 as a treatment for uterine myomas[8], it has been widely performed worldwide as a minimally invasive alternative treatment compared to total hysterectomy. The effectiveness of this treatment was reportedly comparable to that of surgical treatments such as total hysterectomy and myomectomy in terms of improvement of clinical symptoms such as heavy menstrual bleeding and patient satisfaction[9-12]. However, its complications include postoperative fever (4.0%), pain (2.9%), and endometritis (1.1%)[11-14].

As another conservative treatment method for uterine myomas, MRI-guided focused ultrasound is available; the details of which have been described in previous studies[15]. This is a method of treating myomas noninvasively from outside the body using high-intensity focused ultrasound, which uses high-output ultrasound to convert it into thermal energy within the tissue away from the probe, inducing coagulation necrosis in the targeted area while observing it in real time by combining it with MRI. This treatment has been reported to reduce the volume of uterine myomas and improve clinical symptoms such as heavy menstrual bleeding[16-18]. However, ablation of large myomas requires time, and there are concerns regarding increased uterine myoma size and recurrence of clinical symptoms in obese patients and patients with degenerative uterine myomas caused by the uncertainty of the ablation effect[16-18].

Furthermore, as a conservative treatment method for uterine myomas, ultrasound-guided transcervical microwave myolysis (TCMM) using microwaves, as in the present cases, is available. In addition to conventional MEA, this method uses a modified needle-shaped sounding applicator for MEA to ablate uterine myomas themselves with microwaves. Reportedly, the clinical effects of MEA include improving heavy menstrual bleeding and anemia as well as shrinking uterine myomas[19,20]. However, because the area to be ablated is approximately 6 mm from the surface of the sounding applicator, larger myomas require time for ablation. In addition, the sounding applicator used for ablation has a diameter of 4 mm, which is thick and raises concerns regarding procedure invasiveness. Furthermore, it is unclear which method was more successful, conventional MEA or TCMM, because the therapeutic effect of TCMM alone has not been examined.

In contrast, based on the perspective about fertility preservation in conservative treatment of uterine fibroids, UAE may also be selected for those wishing to have children in future. Complications other than those mentioned above include ovarian dysfunction, secondary amenorrhea associated with endometrial atrophy/Lumenal adhesions, and other complications that may affect fertility[9,11,12,21]. Therefore, the indication for UAE in patients who desire to bear a child must be carefully considered. Possible effects on the ovaries after UAE include ovarian failure caused by decreased ovarian blood flow and damage to the fallopian tubes due to infection and resulting infertility. Although there have been multiple reports of pregnancies and deliveries after UAE, there have also been reports of increased miscarriage rates[11,12,22] and placental abnormalities such as placenta accrete[11,12,23] in pregnancies after UAE. Therefore, careful treatment selection for patients who wish to bear a child and strict perinatal management in cases of pregnancy after this treatment should be considered.

Conventional MEA is not indicated for women who desire to bear a child because it is a method to decrease menstrual flow by ablating the endometrium, including its basal layer, thereby inhibiting cyclical endometrial regeneration. In addition, MRgFUS, a conservative treatment for uterine myomas, is not indicated for patients in Japan who desire to bear a child. However, there are several reports of pregnancies after treatment with MRgFUS. These indicate that normal pregnancy outcomes and normal vaginal deliveries are possible[16]. However, given the small number of studies, future, well-powered, and prospective investigations are warranted. TCMM is not indicated for patients who wish to bear a child because it also involves MEA.

The method presented in the current report may minimize the reduction of blood flow to the uterus and ovaries because the microwave directly ablates the feeding vessels to the uterine myomas without ablating the endometrium. If the method we used in the present cases can be expected to improve clinical symptoms, it can potentially become one of the conservative treatment options for uterine myomas wherein fertility preservation is desired. The trend toward late marriage and childbearing has become more pronounced in recent years due to changes in women's lifestyles. Symptomatic uterine myomas in sexually mature women often require not only minimally invasive treatment but also management with consideration for fertility preservation.

In the future, we would like to compile cases of this procedure in patients with uterine myomas associated with heavy menstrual bleeding and verify various aspects of this treatment method, through long-term follow-up, including clinical efficacy and recurrence in heavy menstrual bleeding and other conditions, safety, postoperative changes in hormone dynamics, pregnancy course after pregnancy is established, outcome of delivery, and indication of this procedure.

Ultrasound-guided microwave ablation of uterine myomas was as effective and safe as conventional MEA and reduced the maximum diameter of uterine myomas. This technique has the potential to be a novel treatment method for heavy menstrual bleeding caused by uterine myomas.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Junior JMA, Brazil S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Domenico L Jr, Siskin GP. Uterine artery embolization and infertility. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;9:7-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wu G, Li R, He M, Pu Y, Wang J, Chen J, Qi H. A comparison of the pregnancy outcomes between ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation and laparoscopic myomectomy for uterine fibroids: a comparative study. Int J Hyperthermia. 2020;37:617-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kakinuma T, Kaneko A, Kakinuma K, Matsuda Y, Yanagida K, Takeshima N, Ohwada M. Effectiveness of treating menorrhagia using microwave endometrial ablation at a frequency of 2.45 GHz. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:5653-5659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sharp NC, Cronin N, Feldberg I, Evans M, Hodgson D, Ellis S. Microwaves for menorrhagia: a new fast technique for endometrial ablation. Lancet. 1995;346:1003-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Hodgson DA, Feldberg IB, Sharp N, Cronin N, Evans M, Hirschowitz L. Microwave endometrial ablation: development, clinical trials and outcomes at three years. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:684-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nakamura K, Nakayama K, Sanuki K, Minamoto T, Ishibashi T, Sato E, Yamashita H, Ishikawa M, Kyo S. Long-term outcomes of microwave endometrial ablation for treatment of patients with menorrhagia: A retrospective cohort study. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:7783-7790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kumar V, Chodankar R, Gupta JK. Endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding. Womens Health (Lond). 2016;12:45-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ravina JH, Herbreteau D, Ciraru-Vigneron N, Bouret JM, Houdart E, Aymard A, Merland JJ. Arterial embolisation to treat uterine myomata. Lancet. 1995;346:671-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 791] [Cited by in RCA: 697] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gupta JK, Sinha A, Lumsden MA, Hickey M. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;CD005073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dariushnia SR, Nikolic B, Stokes LS, Spies JB; Society of Interventional Radiology Standards of Practice Committee. Quality improvement guidelines for uterine artery embolization for symptomatic leiomyomata. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:1737-1747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Keung JJ, Spies JB, Caridi TM. Uterine artery embolization: A review of current concepts. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;46:66-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ludwig PE, Huff TJ, Shanahan MM, Stavas JM. Pregnancy success and outcomes after uterine fibroid embolization: updated review of published literature. Br J Radiol. 2020;93:20190551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kitamura Y, Ascher SM, Cooper C, Allison SJ, Jha RC, Flick PA, Spies JB. Imaging manifestations of complications associated with uterine artery embolization. Radiographics. 2005;25 Suppl 1:S119-S132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Martin J, Bhanot K, Athreya S. Complications and reinterventions in uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids: a literature review and meta analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36:395-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fennessy FM, Tempany CM. MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery of uterine leiomyomas. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:1158-1166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fischer K, McDannold NJ, Tempany CM, Jolesz FA, Fennessy FM. Potential of minimally invasive procedures in the treatment of uterine fibroids: a focus on magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound therapy. Int J Womens Health. 2015;7:901-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kröncke T, David M. MR-Guided Focused Ultrasound in Fibroid Treatment - Results of the 4th Radiological-Gynecological Expert Meeting. Rofo. 2019;191:626-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kong CY, Meng L, Omer ZB, Swan JS, Srouji S, Gazelle GS, Fennessy FM. MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery for uterine fibroid treatment: a cost-effectiveness analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203:361-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tsuda A, Kanaoka Y. Outpatient transcervical microwave myolysis assisted by transabdominal ultrasonic guidance for menorrhagia caused by submucosal myomas. Int J Hyperthermia. 2015;31:588-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kanaoka Y, Yoshida C, Fukuda T, Kajitani K, Ishiko O. Transcervical microwave myolysis for uterine myomas assisted by transvaginal ultrasonic guidance. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2009;35:145-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Khaund A, Lumsden MA. Impact of fibroids on reproductive function. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22:749-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Homer H, Saridogan E. Uterine artery embolization for fibroids is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:324-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pron G, Mocarski E, Bennett J, Vilos G, Common A, Vanderburgh L; Ontario UFE Collaborative Group. Pregnancy after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata: the Ontario multicenter trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:67-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |