Peer-review started: May 26, 2015

First decision: June 18, 2015

Revised: July 9, 2015

Accepted: November 3, 2015

Article in press: November 4, 2015

Published online: March 12, 2016

Leptin, an adipokine responsible for body weight regulation, may be involved in pathological processes related to inflammation in joint disorders including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteoarthritis, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). These arthropathies have been associated with a wide range of systemic and inflammatory conditions including cardiovascular disease, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. As a potent mediator of immune responses, leptin has been found in some studies to play a role in these disorders. Furthermore, current potent biologic treatments effectively used in PsA including ustekinumab (an interleukin 12/23 blocker) and adalimumab (a tumor necrosis factor-alpha blocker also used in RA) have been found to increase leptin receptor expression in human macrophages. This literature review aims to further investigate the role leptin may play in the disease activity of these arthropathies.

Core tip: Leptin is an adipokine well known for its role in metabolism and body weight regulation. More recently, it has gained recognition as a potential contributor to the pathogenesis of inflammatory disorders. Numerous studies reveal elevated leptin levels in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Similarly, a link between severity of osteoarthritis and leptin levels has been suggested. At the same time, little research on the role of leptin in the pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis has been conducted. Further investigation on these relationships could provide for better-targeted treatment of these rheumatic diseases and their systemic manifestations.

- Citation: Mounessa J, Voloshyna I, Glass AD, Reiss AB. Role of leptin in the progression of psoriatic, rheumatoid and osteoarthritis. World J Rheumatol 2016; 6(1): 9-15

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3214/full/v6/i1/9.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5499/wjr.v6.i1.9

Approximately one in five adults in the United States reports having the medical diagnosis of arthritis[1]. Arthritis and other rheumatic conditions (AORC) were found to cost equivalent to 1.2% of the 2003 United States gross domestic product, and this number is estimated to increase in the coming years[2]. While dozens of different types exist, three of the most common are rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteoarthritis (OA), and psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

While the pathogenesis of each type of arthritis is unique, as a whole, AORC are associated with a number of comorbidities and chronic conditions including hypertension, physical inactivity, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and smoking[3]. Other inflammatory diseases including atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease also occur at a higher rate[1]. In recent years, numerous studies have investigated such relationships.

More specifically, leptin is an adipokine derived from adipose tissue that has recently been suggested to contribute to the pathogenesis of RA, OA, PsA and their systemic manifestations[4-6]. It is a 167-amino acid peptide with a four-helix bundle motif similar to that of a cytokine. Leptin receptors belong to the class I cytokine receptor family.

Although six isoforms of receptor have been identified, only two are known to be involved in intracellular signaling. Binding of leptin to its longest receptor isoform activates numerous intracellular signals following JAK2 activation, which have been associated with a wide variety of biological actions in different tissues[7]. The leptin receptor has been postulated to play a role in signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-dependent T cell differentiation, by influencing the downstream pro-inflammatory milieu of IL-23, which includes interferon-gamma, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, and IL-17[8].

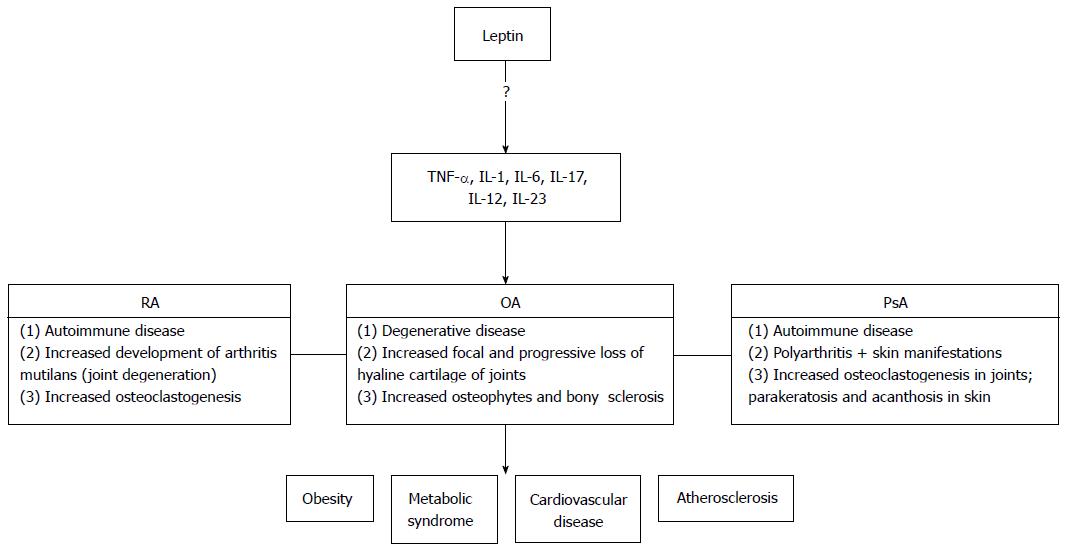

Numerous studies have also aimed to identify leptin’s potential role in the progression of these arthropathies (Figure 1). Most of these studies, however, focus on RA and OA, but not PsA. To date, these findings also seem conflict, and no clear conclusions have been reported. In this article, we aim to explore whether or not a link exists between leptin and RA, OA, or PsA disease activity.

A review of literature was performed on Cochrane and PubMed databases using the keywords “leptin” and “arthritis.” Study inclusion criteria were: (1) studies conducted between 01/01/1990 through 10/01/2015; (2) studies on human subjects with either RA, OA, or PsA; (3) studies available in English; (4) randomized controlled trials or clinical trials with total n≥ 20 and P < 0.05; (5) studies reporting on leptin and disease activity; and (6) studies with original data. Studies that did not meet these criteria, including case reports, duplicate studies, studies with n < 20, and studies without significant or original data were excluded. Studies that meet criteria, but are not in English are described separately as they are evaluated based on the abstract in English.

A total of 34 publications met the criteria listed above. Of these, 24 studies pertained to RA, 9 to OA, and one to PsA. The studies were further categorized into whether the studies identified: (1) no relationship between leptin and disease activity; (2) a positive correlation between leptin and disease activity; and (3) a negative correlation between leptin and disease activity (Table 1).

| RA | OA | PsA | |||||||||

| Ref. | Negative correlation (n1) | Positive correlation (n1) | No correlation (n1) | Ref. | Negative correlation (n1) | Positive correlation (n1) | No correlation (n1) | Ref. | Negative correlation (n1) | Positive correlation (n1) | No correlation (n1) |

| [25] | 37 | - | - | [42] | 117 | - | - | [43] | - | 41 | - |

| [26] | 31 | - | - | [34] | - | 193 | - | - | - | - | - |

| [29] | 40 | - | [38] | - | 543 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [30] | 167 | - | - | [29] | 18 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [31] | 515 | - | - | [40] | - | 20 | - | - | - | - | - |

| [17] | - | 76 | [41] | - | 219 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [18] | - | 30 | - | [35] | - | - | 172 | - | - | - | - |

| [19] | - | 31 | - | [36] | - | - | 2477 | - | - | - | - |

| [21] | - | 141 | [37] | - | - | 44 | - | - | - | - | |

| [22] | - | 127 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [23] | - | 242 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [28] | - | 169 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [9] | - | - | 32 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [10] | - | - | 33 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [11] | - | - | 16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [12] | - | - | 197 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [13] | - | - | 253 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [14] | - | - | 152 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [15] | - | - | 119 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [16] | - | - | 791 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [20] | - | - | 38 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [27] | - | - | 58 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [32] | - | - | 52 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [33] | - | - | 12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Total | 5 | 7 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | - | 1 | - |

The largest number of studies pertained to the role of leptin in the disease activity of RA (n = 24). About 50% of the studies suggested no association (n = 12), while 29% of the 24 studies suggested a positive correlation between leptin and RA disease activity (n = 7), and 21% of the studies suggested a negative correlation (n = 5).

Numerous publications report no significant change in serum leptin levels in RA patients treated with common anti-rheumatic drugs including adalimumab and infliximab. A study on 32 Caucasian RA patients revealed that after 12 wk of anti-TNF treatment with adalimumab, typical measures of inflammation (swollen joints, tender joints, global assessment of pain, IL-6 serum levels) markedly decreased, while serum leptin levels did not[9]. This was also found to be true in another study after 16 wk of adalimumab treatment[10]. A 2012 report investigating the effect of one year of treatment with the chimeric anti-TNF-alpha monoclonal antibody infliximab on plasma leptin concentration further revealed that while treatment with infliximab resulted in enhancement in leptin concentration, there was no significant correlation between disease activity and plasma leptin concentration[11].

Several studies have also reported no significant correlation between radiographic progression of RA and serum leptin levels[12-14]. In one study on 253 patients with RA from the Early Arthritis cohort, no association was found between serum leptin, visfatin, resistin, adipsin, IL-6, or TNF-alpha levels and RA disease progression after correcting for age, sex, treatment strategy, body mass index (BMI), and the presence of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies[13]. Interestingly, they all suggest that a link between serum adiponectin levels and radiographic progression of disease exists. Patients with high levels of adiponectin at baseline were also found to have significantly higher odds of radiographic progression when compared to those with high levels of leptin or resistin[15].

In an investigation of the association between circulating leptin and adiponectin levels and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with RA, it was suggested that leptin and adiponectin are markers of fat mass rather than independent metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease[16].

On the other hand, a larger number of studies point to the harmful role leptin may play in the pathogenesis of RA or its systemic manifestations. A 2003 report examining 76 RA subjects revealed that RA patients had significantly higher leptin production when compared to 34 healthy controls[17]. At the same time, they were found to have significantly lower synovial fluid leptin levels, perhaps suggesting in situ consumption of this molecule in the progression of RA[17].

Interestingly, Härle et al[18] showed that patients with RA exhibited a negative correlation between serum leptin and androstenedione levels, suggesting a link between chronic inflammation and a hypoandrogenic state.

In 2006, a comparative analysis of 31 RA patients and 18 controls revealed that patients with RA had considerably higher plasma levels of leptin, adiponectin, and visfatin, when compared to healthy controls[19]. Another study added that leptin levels were linked to higher fat mass in RA patients[20]. A 2011 study revealed that higher serum leptin levels found in RA were positively associated not only with BMI, but also with C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (an inflammatory biomarker for RA)[21]. Most recently, Xibillé-Friedmann et al[22] found that higher leptin levels at baseline predicted higher disease activity severity at six months.These studies identify a possible role leptin may play in the body composition and disease severity in RA patients.

More specifically, a South Korean study of 242 RA subjects found that persistent LDL cholesterolemia in synergy with serum leptin contributed to radiographic progression of RA in patients over the course of two years[23]. RA patients with hypertension were also found to have increased levels of leptin and homocysteine, after adjustment for age, sex, race, smoking, BMI, and corticosteroid and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs use[24].

Furthermore, the multi-biomarker disease activity (MBDA) score is a recently developed tool used to assess disease activity and response to treatment in RA patients in numerous studies. The MBDA score is calculated using the concentrations of twelve biomarkers, one of which is leptin. The relationship between MBDA score was found to significantly correlate with disease activity, radiographic disease progression, and remission rate in 37 patients with RA, including 31 women and 6 men[25].

At the same time, other studies identify a potentially protective role of leptin in the progression of RA and its associated systemic diseases. In 2005, an evaluation of 31 patients with active RA in The Netherlands demonstrated that baseline plasma leptin levels inversely correlated with the degree of inflammation as determined by CRP and IL-6 levels[26]. Anti-TNF treatment with adalimumab did not change plasma leptin concentration in this study or in a later study[27].

In 2010, Rho’s group obtained coronary calcium scores on 169 patients with RA and found that in leptin concentrations were significantly associated with a decreased risk of coronary calcification related to insulin resistance[28]. That same year, a sub-study of the Swefot (Swedish Pharmacotherapy) study reported that markers of bone resorption were significantly decreased in patients randomized to both anti-TNF and sulphasalazine/hydroxychloroquine treatment groups at one year, and leptin concentrations significantly increased at two years. Anti-TNF agents were interestingly found to cause a significant increase in fat mass at two years, when compared to the other treatment group (3.8 kg vs 0.4 kg) despite reduction in disease activity[29].

In terms of radiographic findings, a 2009 publication by Rho et al[30] evaluated 167 RA patients and 91 control subjects and suggested that leptin concentrations were negatively correlated with radiographic joint damage. It is important to note, however, that the significance of this finding disappeared after adjustment for BMI. More recently, a 2013 study found that RA patients with poor radiographic outcomes had significantly higher baseline CRP levels and significantly lower baseline leptin levels[31].

In addition to those published in English, two human RA studies not in English are noted. A prospective, cross sectional study of 52 RA patients from Poland showed lower serum leptin in RA patients than in controls and no relationship between serum leptin and BMI or CRP and no influence of gender or treatment[32]. A study of 49 RA patients from Japan found leptin level correlated to BMI in both RA and healthy subjects, no difference in leptin level between RA and healthy subjects and no correlation of leptin to CRP or RA stage[33].

A total of 9 studies on patients with OA met the criteria for inclusion in this paper. Of these, one-third suggested no role for leptin in disease activity. Fifty-six percent of studies identified a positive correlation between leptin levels and disease activity, while only 11% supported a negative correlation.

In a cross-sectional study of patients with hip OA, it was found that serum leptin levels did not correlate with the severity of osteophytes[34]. Another study further suggested that no correlation exists between synovial fluid inflammation and serum leptin levels in 172 patients with severe knee OA[35]. Finally, when a sample of 2477 subjects with OA in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) were investigated, it was found that once again, no significant association between serum leptin and OA status existed[36].

Numerous studies have also reported a potentially harmful role for leptin in the pathogenesis of OA and its systemic manifestations. In 2012, Massengale’s group investigated the relationship between adipokine concentrations and hand X-rays in patients with arthritis, and revealed that leptin, BMI, and a history of coronary artery disease were linked with higher rates of chronic hand pain[37].

In 2013, participants in the Michigan Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation underwent bilateral knee radiographs that were associated with leptin levels at baseline and followed up over the course of ten years. Women with OA were found to have significantly higher serum leptin levels compared to those who did not have knee OA at baseline and at the ten-year follow up[38]. In another study, synovial fluid collected from 18 patients with end-stage knee OA and 16 control donors was analyzed for 47 cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors and revealed that leptin, IL-12, macrophage-inflammatory protein (MIP-1B), and soluble CD40 levels were higher in patients with OA[39]. A cross sectional study of patients with end stage OA of the hip (n = 123) and knee (n = 96) confirmed an association between joint pain and synovial fluid leptin concentration[40].

Furthermore, when total RNA from knee lateral tibial and medial tibial plateaus was isolated in a 2013 study, immunohistochemical staining showed that protein expression of leptin was strong in osteoarthritic lateral tibial regions where significant degeneration was found[41].

On the other hand, a study examining the relationship between adipokines and biomarkers of bone and cartilage metabolism revealed that baseline leptin was significantly associated with increased levels of bone formation biomarkers including osteocalcin and PINP (amino peptide from type I procollagen) over two years. However, it is important to note that soluble leptin receptor (sOB-Rb) was linked to a significant reduction in the cartilage biosynthesis marker PIIANP (amino peptide from type IIA procollagen), increased cartilage defects score, and increase loss of volume over the course of two years[42].

There has been limited research regarding the role of leptin in the pathogenesis of PsA. In 2012, one study revealed that patients with PsA had higher osteoclast numbers, which were positively associated with increased serum levels of TNF-alpha, RANKL, and leptin. These 41 patients were found to have increased erosion, joint-space narrowing, osteolysis, and new bone formation. The opposite relationship was seen with adiponectin, as levels were decreased in PsA patients[43].

Several recent studies have investigated the roles of commonly used anti-psoriatic drugs on leptin level. In one study, patients who received six months of treatment with the biologic anti-TNF agent adalimumab were not found to have any significant changes in their serum leptin levels when compared to baseline. In a different study, patients treated with TNF-alpha inhibitors for the same amount of time were actually shown to have lower leptin levels after treatment. These findings are in contrast to a study done by our group, which compares the impact of adalimumab and ustekinumab (an IL-12/23 inhibitor) on leptin and leptin receptor expression in THP-1 human macrophages[44]. In our hands, both drugs up-regulated expression of leptin in THP-1 macrophages. Ustekinumab was also found to enhance the expression of leptin-receptor in a dose dependent manner. Our work is macrophage-specific and does not reflect other cell types that may contribute to serum leptin levels.

Obesity is common in patients with psoriasis or PsA and so are obesity-related complications[45]. Anti-TNF therapy may aggravate this problem by causing further weight gain[46]. Excess leptin produced by macrophages in PsA patients given biologic medications may contribute to obesity-related inflammation. This controversy is ongoing and needs resolution so that PsA can be treated optimally.

Further studies identifying the mechanism of action of leptin as well as the pathway through which ustekinumab and anti-TNF agents alter expression of leptin and its receptor could lead to new preventive measures to avoid systemic disease manifestations and ultimately decrease morbidity and mortality.

Leptin, an adipokine derived from adipose tissue, has a well-established role of maintaining metabolic homeostasis and regulating body weight. Recently, its role in the progression of inflammatory and rheumatic diseases has been an area of active research. The present paper highlights that although numerous studies have investigated its role in RA and OA, results are conflicting. In total, nearly 80% of the studies suggest either no role or a potentially harmful role for leptin in the pathogenesis of RA, OA or PsA. The underlying reason for discrepancies among the studies is unclear, but may be related to small sample size, unknown metabolic factors such as diabetes or thyroid disorder, circadian rhythm effects, leptin receptor levels or differences in genetic background or leptin sensitivity of various populations or other factors not considered. Clearly, these suggestions are speculative and resolution requires large-scale prospective studies.

It is important to note the lack of research published on leptin’s role in the pathogenesis of PsA. While RA, OA, and PsA share common symptomologies and features, they are pathologically distinct. RA is characterized by an auto-immune increase in osteoclast formation and joint derangement. OA is a degenerative joint disease with focal and progressive loss of hyaline cartilage of the joints, osteophytes, and bony sclerosis. In PsA, auto-immune skin and poly-arthritic joint disease are seen.

All three of these diseases are associated with inflammatory mediators and systemic manifestations including metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and atherosclerosis. At the same time, it is uncertain whether leptin functions in a similar or different manner in these pathologies. In other words, leptin’s role in RA or OA cannot be directly transferrable to its role in PsA.

The major biologic treatments for PsA include the TNF-alpha inhibitors and the interleukin-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab[47]. Future research on whether leptin participates in the pathogenesis of PsA could allow for better understanding of the impact of these treatments on leptin and the creation of more effective treatments that could specifically address the adipokine.

P- Reviewer: Cavallasca JA, Gonzalez EG, Rothschild BM S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation--United States, 2010-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:869-873. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National and state medical expenditures and lost earnings attributable to arthritis and other rheumatic conditions--United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:4-7. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Murphy L, Bolen J, Helmick CG, Brady TJ. Comorbidities Are Very Common Among People With Arthritis. 20th National Conference on Chronic Disease Prevention and Control, CDC, February 2009. . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Toussirot É, Michel F, Binda D, Dumoulin G. The role of leptin in the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Life Sci. 2015;140:29-36. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Scotece M, Mobasheri A. Leptin in osteoarthritis: Focus on articular cartilage and chondrocytes. Life Sci. 2015;140:75-78. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chimenti MS, Ballanti E, Perricone C, Cipriani P, Giacomelli R, Perricone R. Immunomodulation in psoriatic arthritis: focus on cellular and molecular pathways. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:599-606. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kontny E, Plebanczyk M, Lisowska B, Olszewska M, Maldyk P, Maslinski W. Comparison of rheumatoid articular adipose and synovial tissue reactivity to proinflammatory stimuli: contribution to adipocytokine network. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:262-267. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S. 20 years of leptin: human disorders of leptin action. J Endocrinol. 2014;223:T63-T70. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 181] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Härle P, Sarzi-Puttini P, Cutolo M, Straub RH. No change of serum levels of leptin and adiponectin during anti-tumour necrosis factor antibody treatment with adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:970-971. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Klaasen R, Herenius MM, Wijbrandts CA, de Jager W, van Tuyl LH, Nurmohamed MT, Prakken BJ, Gerlag DM, Tak PP. Treatment-specific changes in circulating adipocytokines: a comparison between tumour necrosis factor blockade and glucocorticoid treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1510-1516. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kopec-Medrek M, Kotulska A, Widuchowska M, Adamczak M, Więcek A, Kucharz EJ. Plasma leptin and neuropeptide Y concentrations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, a TNF-α antagonist. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:3383-3389. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Giles JT, Allison M, Bingham CO, Scott WM, Bathon JM. Adiponectin is a mediator of the inverse association of adiposity with radiographic damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1248-1256. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Klein-Wieringa IR, van der Linden MP, Knevel R, Kwekkeboom JC, van Beelen E, Huizinga TW, van der Helm-van Mil A, Kloppenburg M, Toes RE, Ioan-Facsinay A. Baseline serum adipokine levels predict radiographic progression in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2567-2574. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Giles JT, van der Heijde DM, Bathon JM. Association of circulating adiponectin levels with progression of radiographic joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1562-1568. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dessein PH, Norton GR, Badenhorst M, Woodiwiss AJ, Solomon A. Rheumatoid arthritis impacts on the independent relationships between circulating adiponectin concentrations and cardiovascular metabolic risk. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:461849. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Meyer M, Sellam J, Fellahi S, Kotti S, Bastard JP, Meyer O, Lioté F, Simon T, Capeau J, Berenbaum F. Serum level of adiponectin is a surrogate independent biomarker of radiographic disease progression in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the ESPOIR cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R210. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bokarewa M, Bokarew D, Hultgren O, Tarkowski A. Leptin consumption in the inflamed joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:952-956. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 136] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Härle P, Pongratz G, Weidler C, Büttner R, Schölmerich J, Straub RH. Possible role of leptin in hypoandrogenicity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:809-816. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Otero M, Lago R, Gomez R, Lago F, Dieguez C, Gómez-Reino JJ, Gualillo O. Changes in plasma levels of fat-derived hormones adiponectin, leptin, resistin and visfatin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1198-1201. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 382] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Toussirot E, Nguyen NU, Dumoulin G, Aubin F, Cédoz JP, Wendling D. Relationship between growth hormone-IGF-I-IGFBP-3 axis and serum leptin levels with bone mass and body composition in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44:120-125. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yoshino T, Kusunoki N, Tanaka N, Kaneko K, Kusunoki Y, Endo H, Hasunuma T, Kawai S. Elevated serum levels of resistin, leptin, and adiponectin are associated with C-reactive protein and also other clinical conditions in rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 2011;50:269-275. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xibillé-Friedmann DX, Ortiz-Panozo E, Bustos Rivera-Bahena C, Sandoval-Ríos M, Hernández-Góngora SE, Dominguez-Hernandez L, Montiel-Hernández JL. Leptin and adiponectin as predictors of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:471-477. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Park YJ, Cho CS, Emery P, Kim WU. LDL cholesterolemia as a novel risk factor for radiographic progression of rheumatoid arthritis: a single-center prospective study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68975. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Manavathongchai S, Bian A, Rho YH, Oeser A, Solus JF, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Stein CM. Inflammation and hypertension in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:1806-1811. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yamaoka K, Kubo S, Sonomoto K, Hirata S, Cavet G, Bolce R, Rowe M, Chernoff D, Defranoux N, Saito K. Correlation of a multi-biomarker disease activity (vectra DA) score with clinical disease activity and its components with radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tofacitinib [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum-US. 2012;64:S914-S915. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Popa C, Netea MG, Radstake TR, van Riel PL, Barrera P, van der Meer JW. Markers of inflammation are negatively correlated with serum leptin in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1195-1198. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 117] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Popa C, Netea MG, de Graaf J, van den Hoogen FH, Radstake TR, Toenhake-Dijkstra H, van Riel PL, van der Meer JW, Stalenhoef AF, Barrera P. Circulating leptin and adiponectin concentrations during tumor necrosis factor blockade in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:724-730. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rho YH, Chung CP, Solus JF, Raggi P, Oeser A, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Stein CM. Adipocytokines, insulin resistance, and coronary atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1259-1264. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Engvall IL, Tengstrand B, Brismar K, Hafström I. Infliximab therapy increases body fat mass in early rheumatoid arthritis independently of changes in disease activity and levels of leptin and adiponectin: a randomised study over 21 months. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R197. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 86] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rho YH, Solus J, Sokka T, Oeser A, Chung CP, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Pincus T, Stein CM. Adipocytokines are associated with radiographic joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1906-1914. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 147] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mozaffarian N, Smolen JS, Devanarayan V, Hong F, Kavanaugh A. Biomarkers identify radiographic progressors and clinical responders among patients with early rheumatoid arthritis [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:398. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tokarczyk-Knapik A, Nowicki M, Wyroślak J. [The relation between plasma leptin concentration and body fat mass in patients with rheumatoid arthritis]. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:761-767. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Nishiya K, Nishiyama M, Chang A, Shinto A, Hashimoto K. [Serum leptin levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis are correlated with body mass index]. Rinsho Byori. 2002;50:524-527. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Stannus OP, Jones G, Quinn SJ, Cicuttini FM, Dore D, Ding C. The association between leptin, interleukin-6, and hip radiographic osteoarthritis in older people: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R95. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | de Boer TN, van Spil WE, Huisman AM, Polak AA, Bijlsma JW, Lafeber FP, Mastbergen SC. Serum adipokines in osteoarthritis; comparison with controls and relationship with local parameters of synovial inflammation and cartilage damage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:846-853. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 184] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Massengale M, Reichmann WM, Losina E, Solomon DH, Katz JN. The relationship between hand osteoarthritis and serum leptin concentration in participants of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R132. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Massengale M, Lu B, Pan JJ, Katz JN, Solomon DH. Adipokine hormones and hand osteoarthritis: radiographic severity and pain. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47860. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Harlow SD, Mancuso P, Jacobson J, Mendes de Leon CF, Nan B. Association of leptin levels with radiographic knee osteoarthritis among a cohort of midlife women. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:936-944. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Beekhuizen M, Gierman LM, van Spil WE, Van Osch GJ, Huizinga TW, Saris DB, Creemers LB, Zuurmond AM. An explorative study comparing levels of soluble mediators in control and osteoarthritic synovial fluid. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:918-922. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Lübbeke A, Finckh A, Puskas GJ, Suva D, Lädermann A, Bas S, Fritschy D, Gabay C, Hoffmeyer P. Do synovial leptin levels correlate with pain in end stage arthritis? Int Orthop. 2013;37:2071-2079. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chou CH, Wu CC, Song IW, Chuang HP, Lu LS, Chang JH, Kuo SY, Lee CH, Wu JY, Chen YT. Genome-wide expression profiles of subchondral bone in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R190. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Berry PA, Jones SW, Cicuttini FM, Wluka AE, Maciewicz RA. Temporal relationship between serum adipokines, biomarkers of bone and cartilage turnover, and cartilage volume loss in a population with clinical knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:700-707. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Xue Y, Jiang L, Cheng Q, Chen H, Yu Y, Lin Y, Yang X, Kong N, Zhu X, Xu X. Adipokines in psoriatic arthritis patients: the correlations with osteoclast precursors and bone erosions. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46740. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Voloshyna I, Mounessa J, Carsons SE, Reiss AB. Effect of inhibition of interleukin-12/23 by ustekinumab on the expression of leptin and leptin receptor in human THP-1 macrophages. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Cañete JD, Mease P. The link between obesity and psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1265-1266. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Renzo LD, Saraceno R, Schipani C, Rizzo M, Bianchi A, Noce A, Esposito M, Tiberti S, Chimenti S, DE Lorenzo A. Prospective assessment of body weight and body composition changes in patients with psoriasis receiving anti-TNF-α treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:446-451. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Brezinski EA, Armstrong AW. An evidence-based review of the mechanism of action, efficacy, and safety of biologic therapies in the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:1930-1942. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |