Published online Oct 19, 2019. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v9.i6.83

Peer-review started: April 12, 2019

First decision: June 6, 2019

Revised: July 3, 2019

Accepted: August 21, 2019

Article in press: August 21, 2019

Published online: October 19, 2019

Dissociation, which is defined as the failure to associate consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, and behavior into an integrated whole, has long been assumed to be generated by trauma. If dissociation is a product of trauma exposure, then dissociation would be a major mental health outcome observed in studies of disaster survivors. Although some studies have examined dissociation in disasters, no systematic literature reviews have been conducted to date on the topic.

To systematically evaluate the literature on the association between disaster and dissociation to determine the prevalence and incidence of dissociation after exposure to disaster and further examine their relationship.

EMBASE, Medline, and PsychINFO were searched from inception to January 1, 2019 to identify studies examining dissociative disorders or symptoms related to a disaster in adult or child disaster survivors and disaster responders. Studies of military conflicts and war, articles not in English, and those with samples of 30 or more participants were excluded. Search terms used were “disaster*” and dissociation (“dissociat*,” “multiple personality,” “fugue,” “psychogenic amnesia,” “derealization,” and “depersonalization”). Reference lists of identified articles were scrutinized to identify studies for additional articles.

The final number of articles in the review was 53, including 36 articles with samples of adults aged 18 and above, 5 of children/adolescents under age 18, and 12 of disaster workers. Included articles studied several types of disasters that occurred between 1989 and 2017, more than one-third (38%) from the United States. Only two studies had a primary aim to investigate dissociation in relation to disaster and none reported data on dissociative disorders. All of the studies used self-report symptom scales; none used structured interviews providing full diagnostic assessment of dissociative disorders or other psychopathology. Several studies mixed exposed and unexposed samples or did not differentiate outcomes between exposure groups. Studies examining associations between dissociation and disaster exposure have been inconclusive. The majority (75%) of the studies compared dissociation with posttraumatic stress, with inconsistent findings. Dissociation was found to be associated with a wide range of other psychiatric disorders, symptoms, and negative emotional, cognitive, and functional states.

The studies reviewed had serious methodological limitations including problems with measurement of psychopathology, sampling, and generation of unwarranted conclusions, precluding conclusions that dissociation is an established outcome of disaster.

Core tip: Almost all existing studies of dissociation in relation to disaster have not focused specifically on this purpose but rather on the relationship of dissociation to other disaster outcomes. Instead of dissociative disorders, broadly defined dissociative phenomena have been examined in disaster survivors. The literature uniformly contains unsurmountable methodological limitations such as reliance on nondiagnostic dissociation measures, lack of temporal specificity to postdisaster time frames, and problems with disaster exposure issues pertaining to sampling, measurement, and analysis. It cannot be concluded from the research that dissociation is an established outcome of disasters.

- Citation: Canan F, North CS. Dissociation and disasters: A systematic review. World J Psychiatr 2019; 9(6): 83-98

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v9/i6/83.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v9.i6.83

The current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition) (DSM-5)[1] defines dissociation as “a disruption of and/or discontinuity in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, and behavior” (p. 291). Dissociative disorders listed and defined in DSM-5 are Dissociative Identity Disorder, Dissociative Amnesia, and Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder, as well as Other Specified Dissociative Disorder and Unspecified Dissociative Disorder. The concept of dissociation was first introduced in the field of medicine in the 1800s by the French physician Pierre Janet who described it as a breakdown of the integration, or the compartmentalization, of the mental processes required for a unified experience of consciousness and of self[2,3]. A variant of dissociation also introduced by Janet was described as "narrowing of the field of consciousness," reflecting reduced capacity to assimilate elements of sensation into complex personal perceptions, a process that has subsequently been linked to hysteria[4,5]. Current concepts of dissociation encompass a wide range of phenomena including highly pathological disturbances of memory such as in states of amnesia, disturbance of consciousness such as in fugue states, and identity disturbance as well as common and benign experiences involving attention such as absorption, daydreaming, and fantasy[6-8].

Dissociation has long been assumed to develop as a mechanism for coping with severe trauma[3,9]. Extensive literature has documented a relationship between trauma and dissociation and elaborated presumptive psychological mechanisms in a “trauma model of dissociation”[10]. It follows logically that if dissociation is a product of trauma exposure, then dissociation would be a major mental health outcome observed in studies of disaster survivors. Despite the publication of some studies of dissociation in disaster survivors, no major systematic reviews of this literature have been conducted. Therefore, the lack of reviews of research on dissociation and disasters in the context of widespread assumptions that trauma generates dissociative psychopathology, the purpose of this article is to provide a systematic review of published studies on dissociation and disaster to determine the prevalence and incidence of dissociation after exposure to disaster and further examine their relationship.

A systematic literature search was undertaken to locate studies examining dissociative disorders or symptoms related to a disaster in adult or child disaster survivors and rescue/recovery workers. Only studies with samples of ≥ 30 were included, because of known problems with non-normal sampling distributions in smaller studies[11]. Articles not in English and studies of military conflicts and war were excluded.

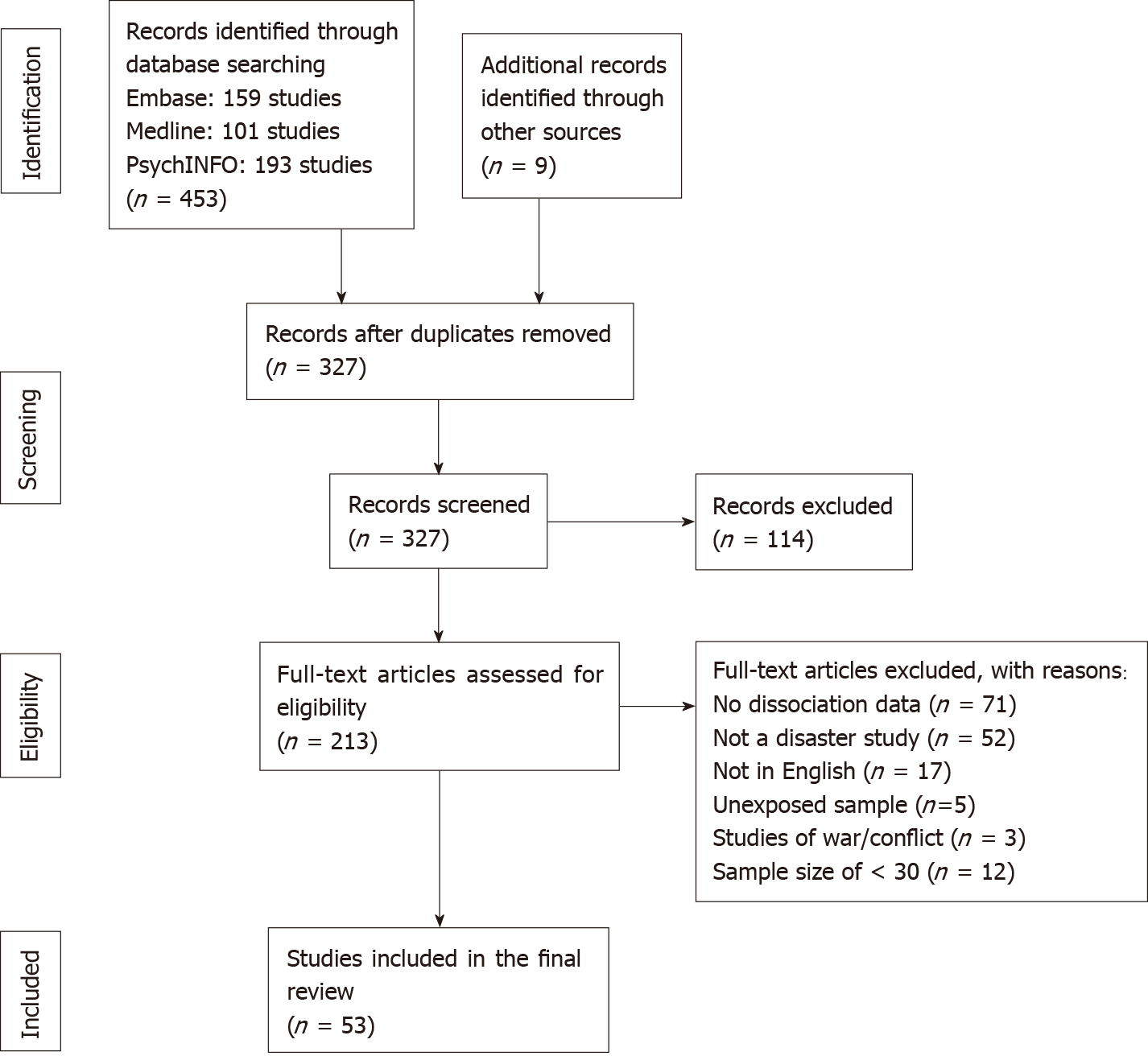

EMBASE, Medline, and PsychINFO were used to identify articles before January 1, 2019. Search terms used were “disaster*” and dissociation (“dissociat*,” “multiple personality,” “fugue,” “psychogenic amnesia,” “derealization,” and “depersonalization”). Reference lists of identified articles were inspected for additional articles. Figure 1 provides a flow chart of this article selection process. The manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist[12]. The search strategy and list of excluded articles with the reason of exclusion are presented in Supplementary table 1.

The quality of the included studies was measured using a modified version of a tool generated for assessing the quality of prevalence studies[13,14]. The features assessed included description of target population, inclusion/exclusion criteria, sampling method, demographic characteristics, information on nonresponders, use of validated and professional-administered diagnostic instruments, and report of prevalence estimates. This instrument has 10-items and allows for the calculation of a total quality score (range = 0-10), with higher summed scores indicating higher study quality.

The Hoy Risk of Bias Tool (RoBT)[15] was used to assess methodological bias. The RoBT consists of 10 items evaluating external (4 items) and internal (6 items) validity. Studies were classified as having a low risk of bias when 8 or more of the 10 items were answered as “yes (low risk),” a moderate risk of bias when 6 to 7 of the questions were answered as “yes (low risk),” and a high risk of bias when 5 or fewer questions were answered as “yes (low risk)”[16].

Simple chi-square analyses were conducted to compare proportions of two different comparison groups with positive findings, substituting Fisher’s exact tests for expected cell sizes of < 5.

The final number of articles in the review was 53, including 36 articles with adult (aged ≥ 18) samples (Table 1), 5 of children/adolescents (< age 18) (Table 2), and 12 of disaster workers (Table 3). These articles, published between 1993 and 2019, included 51 original articles, 1 letter to the editor, and 1 doctoral dissertation. The disasters occurred between 1989 and 2017, and 60% were from countries: United States (n = 20), Netherlands (n = 4), Italy (n = 4), and Turkey (n = 4). The types of disasters included earthquakes (n = 17), explosive accidents (n = 11), terrorist attacks (n = 8), hurricanes/typhoons (n = 7), ferry sinkings (n = 3), firestorms (n = 2), floods (n = 2), tsunamis (n = 2), fires (n = 1), plane crashes (n = 1), train crashes (n = 1), and mass shootings (n = 1). Multiple disasters were examined in five of the articles. Specific population subgroups, namely women, older adults (aged ≥ 60), and pet owners were the focus in three adult survivor studies represented in four articles. More than one-third (36%) of the articles involved longitudinal prospective studies and the remainder described cross-sectional studies.

| Disaster | Sample | Measures | Results |

| Ferry sinking (Baltic Sea 1994)[93,94] | 42 survivors | 3 ASD dissoc. items | 3-mo dissoc. associated with 3-mo and 1-yr but not 14-yr posttraumatic stress |

| Earthquake (Haiti 2010)[28] | 167 exposed volunteers | PDEQ | Mean 27-mo PDEQ score = 25. Dissoc. predicted posttraumatic stress symptoms and depression |

| Explosion (France 2001)[95-97] | 430 survivors from local EDs | PDEQ | 6-mo dissoc. posttraumatic stress at 6 and 15 mo but not 5 yr |

| Train crash (Israel 2005)[50] | 53 survivors | DES, PDEQ | Scores higher in survivors with vs without fibromyalgia (9 vs 2; 20 vs 9) |

| Earthquake (San Francisco, CA 1993)[17] | 100 exposed volunteer college students | SASRQ | All 5 dissoc. subscale scores higher at 1 wk than 4 mo |

| Explosion (Denmark 2004)[29,42] | 169 evacuees | 4 TSC dissociation items | Mean dissoc. Score = 6 (of 12). 3-mo dissoc. predicted 1-yr posttraumatic stress in women only and not 1-yr somatization |

| Floods/ mudslides (Italy 2009)[48] | 287 exposed residents | DES, PDEQ | DES, difficulty identifying feelings, and externally oriented thinking predicted 27-mo PDEQ. PDEQ explained 44% of IES-R |

| Explosion (Belgium 2004)[98] | 1027 exposed residents | PDEQ | 5-mo dissociation predicted 5-mo (not 14-mo) posttraumatic stress |

| 9/11, WTC (NYC 2001)[23] | 1009 Manhattan residents, workers | 1 DTS dissoc. item (event amnesia) | Event amnesia was least endorsed item (2%) |

| Earthquake (NZ, 2011)[40] | 101 exposed treatment seekers | PDEQ (4 items) | Dissoc. predicted posttraumatic stress symptoms, anxiety at 2-8 wk |

| 9/11 Pentagon (Washington, DC 2001)[44] | 77 exposed military, civilian staff | PDEQ | Dissoc. associated with posttraumatic stress (18 vs 5) and alcohol use and negatively with perceived safety |

| 3 technological accidents (Netherland)[99] | 49 affected individuals | PDEQ, SDQ-P | 20-d dissoc. did not predict 6-mo posttraumatic stress symptoms |

| Hurricane Katrina (New Orleans, LA 2005)[100] | 65 exposed pet owners | PDEQ | Dissoc. associated with having to abandon pet (mean PDEQ = 30 vs 23), depression, acute stress, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. |

| Hurricane Katrina (New Orleans, LA 2005)[32] | 117 people in mandatory evacuation zones | PDEQ | Mean PDEQ score = 12 (unknown timing). Dissoc. associated with property damage |

| Earthquakes; floods (Australia/NZ 2010-2011)[101] | 662 exposed residents | PDEQ | Dissoc. associated with posttraumatic stress symptoms and negative beliefs about memory |

| Firestorm (Oakland/Berkeley 1991)[18,102] | 94 referral center help seekers, 93 local students | SASRQ | 1-mo dissoc. associated with 7-9-mo posttraumatic stress symptoms but not intrusions |

| 9/11 WTC (NYC 2001)[24] | 2001 NYC residents | 2 DIS dissoc. panic attack items | 4-5 mo dissoc. associated with posttraumatic stress symptoms, older age, female sex, non-white race, and fear of death or injury |

| Earthquake (Haiti 2010); tsunami (Japan, 2011)[103] | 140 Haiti/12 Japan disaster exposed; 80 other trauma exposed | DES | Dissoc. scores (unknown timing) not different between trauma groups |

| Mass shooting (DeKalb, IL 2008)[25] | 583 female university students | 4 PDEQ items | 2-wk dissoc. predicted 2-wk to 3-mo and 8-mo probable posttraumatic stress |

| Earthquake (Iran 2017)[80] | 230 exposed volunteers from 2 cities | DES, PDEQ | 3-4 mo dissoc. associated with posttraumatic stress |

| Earthquake (Turkey 2011)[26] | 583 randomly sampled residents | DES (with Taxon) | 2-yr DES Taxon membership = 25%. Dissoc. predicted posttraumatic stress symptoms, re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal but not functional impairment |

| Earthquake (Turkey 2011)[27] | 317 volunteer college students | DES (with Taxon) | High (21%) DES Taxon membership (unknown timing). DES predicted posttraumatic stress symptoms. Pathological dissoc. mediated between posttraumatic stress symptoms and ADHD symptoms |

| Earthquake (Italy 2009)[35] | 84 university student volunteers | 14 TSI dissoc. items | 7-yr dissoc. scores in exposed than unexposed. Dissoc. not associated with exposure |

| Hurricane Ike (Texas coast, 2008)[66,104] | 75 older residents | PDEQ | Mean PDEQ = 11. Dissoc. associated with 3-mo posttraumatic stress but not 3-mo depression. Dissoc. not associated with posttraumatic stress trajectories |

| Tsunami (Indonesia 2004)[30] | 660 evacuated Danish tourists | 4 ERDTS dissoc. items | 10-mo dissoc. predicted posttraumatic stress symptoms, depression |

| 9/11 WTC (NYC 2001)[36,105] | 75 exposed NYC residents | PDEQ, DES, CDS, CADDS | Mean PDEQ = 35, DES = 17. 3-mo dissoc. not associated 1-yr posttraumatic stress symptoms. Dissoc. not associated with exposure |

| Explosion (Taiwan 2015)[47] | 116 burn survivors | SDQ | 25-mo dissoc. associated with posttraumatic stress but not depression |

| Fire (Nether-lands, 2000)[31] | 662 residents | PDEQ | Mean PDEQ = 24. 2-3 wk dissoc. not associated with 18-mo or 4-yr posttraumatic stress symptom severity |

| Fire and explosion (Netherlands 2001, 2004)[106] | 94 disaster, 111 non-disaster burn survivors | 3 ADS dissoc. items | 1-wk dissoc. Disaster > others. Disaster: 1-wk dissoc. not associated with 12-mo posttraumatic stress |

| Disaster | Sample | Measures | Results |

| Hurricane Katrina (New Orleans, LA 2005)[41] | 112 exposed students with ≥ 1 other trauma exposure | 9 TSCC dissoc. items | 4-mo to 7-yr dissoc. associated with posttraumatic stress symptoms, anger, anxiety, depression |

| Earthquake (Turkey 2011)[34] | 738 exposed high school students | A-DES | 6-mo dissoc. associated with posttraumatic stress, anxiety, prior mental health problems, metacognitions, but not with age, sex, disaster exposure, prior exposure to trauma |

| Earthquake (Turkey 1999)[33] | 202 exposed, 101 unexposed children | 11 TDGS dissoc. items | Exposed children had higher 4-5 mo perceptual distortions (1.3 vs 1.2), body-self distortions (1.1 vs 1.1) (range = 1-3 for both subscales) |

| Ferry disaster (South Korea 2014)[65] | 57 child and adolescent survivors | 3 PDEQ items | 20-mo dissoc. associated with posttraumatic symptoms |

| Earthquake (China 2010)[116] | 753 exposed middle school students | 1 UPRI dissoc. item (derealization) | Majority (77%) positive for derealization. 6-mo derealization predicted PTSD |

| Disaster | Sample | Measures | Results |

| 9/11, WTC (NYC 2001)[38] | 90 disaster workers | PDEQ | Number of 2-3 wk dissoc. symptoms associated with probable ASD |

| Typhoon Haiyan (Philippines 2013)[37] | 61 religiously, spiritually oriented humanitarian aid workers | MBI-HSS (5 depersonalization items) | Mean 8-mo depersonalization score = 1.1 (of 30). Depersonalization associated with negative religious coping but not with indirect exposure, direct exposure, or positive religious coping |

| Earthquake (Japan 2011)[43] | 34 healthcare providers | MBI-HSS (5 depersonal-ization items) | Mean 2-yr depersonalization score = 0.6 (of 30). Depersonalization not associated with general mental health |

| Plane crash (Sioux City, IA 1989)[39] | 207 exposed, 421 unexposed disaster workers | 3 ASD dissoc. items | Number of 2-mo dissoc. symptoms associated with 13-mo posttraumatic stress but not depression. Any 2-mo dissoc. symptoms not associated with 13-mo posttraumatic stress or depression |

| 9/11 WTC (NYC 2001)[46] | 89 disaster responders | PDEQ | 2-wk dissoc. negatively associated with perceived safety |

| Hurricane Katrina (New Orleans, LA 2005)[51] | 441 rescue personnel | PDEQ | 2-yr dissoc. associated with being single, exposure severity, physical victimization |

| Earthquake (Loma Prieta, CA 1989)[67,68] | 198 exposed, 251 unexposed rescue personnel | PDEQ | 1.5-yr dissoc. associated with 3.5-yr posttraumatic stress symptoms, intrusion, avoidance, hyperarousal |

| Earthquake (Italy 2009)[49,120] | 285 healthcare workers at one hospital | MBI-HSS (5 depersonal-ization items) | Mean 6-yr depersonalization score = 1.1 (of 30) Depersonalization associated negatively associated with planning and positively with behavioral disengagement and self-distraction |

| Terror attacks (Norway 2011)[121] | 238 rescue personnel | 5-item scale developed by authors | 8-11 mo dissoc. predicted posttraumatic stress |

| Fire (Netherlands 2000)[45] | 66 ambulance personnel | PDEQ | 2-3 wk dissoc. predicted 18-mo hostility, but not posttraumatic stress symptoms or depression |

The total quality score of the studies ranged from 1 to 5 (out of a maximum possible of 10), indicating that none of the studies included had good quality (Supplementary table 2). According to the RoBT, the majority of studies had a high risk of bias with only three having a moderate risk (Supplementary table 3).

Only two of the studies in the review focused solely on dissociation without including other disaster mental health outcomes such as posttraumatic stress[17,18]. The majority of studies (n = 40) had a primary focus on posttraumatic stress, including dissociation only as a secondary topic, typically examining it in relation to posttraumatic stress. The remaining few studies (n = 10) had a joint focus on posttraumatic stress and dissociation, investigating the relationship between these two entities.

All of the studies used self-report symptom scales; none used structured diagnostic interviews for dissociative disorders. The Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Scale (PDEQ)[19] was used in 49% of the studies and the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES)[20,21] was used in 13%. The Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS)[22] was used to measure depersonalization in four studies. Dissociative symptoms embedded in Criterion B of acute stress disorder were assessed by three studies; two others approximated dissociation respectively with one panic disorder symptom and a single traumatic event-related amnesia item.

Several studies in this review (for example[23-27]) reported dissociation levels in mixed samples of exposed and unexposed survivors without differentiating results between exposure groups. In some studies, references to disaster exposures did not differentiate between disaster trauma exposure specifically, and the experiences of other stressors in the disaster such as property damage or loss of possessions.

The presentation of dissociation data was limited to univariate results in two studies, one[17] documenting a decline in dissociation from 1 wk to 6 mo and the other[23] reporting event amnesia in only 2% of the sample. Demographic factors reported to be associated with dissociation in bivariate comparisons included advanced age[24,28], female sex[24,28-31], African American or Hispanic race[24], and limited education[31].

The findings of associations between dissociation and disaster exposure in the studies reviewed are inconclusive. Dissociation was found to be significantly associated with disaster exposure in three studies. Non-traumatic stressor exposures by themselves or included in a mixed list of traumatic and other stressful disaster exposures were associated with dissociation in a firestorm study[18] and a hurricane study[32], and specific trauma exposures were associated with higher dissociation scores among children in a severe earthquake[33]. Several studies did not identify associations between dissociation and disaster exposures. Dissociation was not found to be associated with disaster trauma exposures or exposure proxies such as physical proximity to the World Trade Center towers in the 9/11 attacks[24], losing significant others or possessions in the disaster[24,34], or being trapped under earthquake rubble[34,35]. A study of survivors of the 9/11 attacks found that levels of dissociation were not associated with immediate life threat in the disaster, indirect exposure via threat to loved ones, or participation in rescue efforts[36]. Depersonalization in disaster workers responding to a typhoon was not found to be associated with contact with disaster survivors or witnessed disaster trauma exposures[37].

Three-fourths (75%) of the studies (40 articles) compared dissociation with posttraumatic stress. These articles used self-report posttraumatic stress measures such as the Impact of Event Scale-Revised, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Checklist, PTSD Symptom Scale, and Child Posttraumatic Stress Disorder-Reaction Index. As for dissociation, none of the studies of posttraumatic stress used structured diagnostic assessment interviews. Of the 25 studies reporting results of bivariate comparisons, 100% reported significant associations between dissociation and posttraumatic stress. Of the 30 studies reporting results of multivariate models, only 60% found significant associations between dissociation and posttraumatic stress, a significantly lower proportion (χ2 = 12.79, df = 1, P < 0.001). Of the 16 longitudinal multivariate studies, only one-fourth (25%) found that dissociation measured shortly after a disaster was associated with long-term posttraumatic stress, significantly less often than in cross-sectional multivariate studies (χ2 = 5.12, df = 1, P = 0.024).

Of the seven studies conducting bivariate comparisons of dissociation with depressive pathology, all reported significant associations (for example[26,28,34,38,39]). Only two of five studies comparing dissociation with depressive pathology in multivariate models reported significant associations[28,30], a significant difference from the bivariate analysis findings (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.021). Other problems found to be positively associated with dissociation in sporadic studies included anxiety[34,40,41], somatization[42], adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder[27], general mental health problems[43], increased postdisaster use of alcohol[44] or tobacco[38], suicidality[26], hopelessness[26], anger[41], hostility[45], feeling unsafe[44,46], fear during the disaster[24,47], alexithymia[48], trauma memory disorganization[47], trauma-related rumination[47], maladaptive coping strategies[49], lower academic achievement[27], greater injury-related functional impairment[47], lower health-related quality of life[26], and fibromyalgia syndrome[50]. Dissociation was also associated with early traumatic experience[51] and religiosity[28]. In the above studies, none were found in which dissociation was not associated with any of these outcomes.

Although there are a number of reviews[52-55], meta-analyses[56,57], and a bibliometric analysis[58] examining the studies on mental health outcomes of disasters, no prior reviews have been published specifically on dissociation associated with disasters even though a few reviews of PTSD and dissociation included very small numbers of disaster studies without specific comment on them[59-62]. The current review found 53 published articles on this topic among adult and child survivors of disasters as well as disaster workers. Only 2 of the 53 studies reviewed was designed for the main purpose of examining the prevalence of dissociation following a disaster. The main purpose of the remaining 51 studies was to examine the occurrence of other outcomes (posttraumatic stress in the majority) after disaster, and dissociation was included only as a secondary outcome in relation to the primary outcome of interest. The quality of the studies reviewed was exceedingly limited by methodological problems inherent in them. Problems with measurement of psychopathology, sampling issues, assessment time frames, and generation of conclusions unwarranted from the data represented serious methodological weaknesses in this literature.

Problems in the instruments of assessment were fundamental limitations in all of the studies reviewed. None used diagnostic instruments assessing accepted standards such as DSM-5 criteria for dissociative disorders; dissociative identity disorder, dissociative amnesia, and depersonalization/derealization disorder were not mentioned in any of these studies’ findings. All depended on symptom measures to assess dissociation, with 72% using the PDEQ, DES, or MBI-HSS. These self-report questionnaires inquire about many kinds of experiences not generally corresponding to the established symptoms of DSM-5 dissociative disorders; these items are then tabulated and summarized into indistinct “dissociation” scores of unclear meaning or significance. The PDEQ, which was used in about half of the studies, collects information about lack of awareness that is not reflected in diagnostic criteria for any dissociative disorder, and its other items do not provide data on symptoms of dissociative identity disorder, dissociative amnesia, or depersonalization/ derealization disorder[63,64]. Numerous studies using the PDEQ have not been faithful to the full instrument (for example[25,40,44,65,66]) or its scoring algorithms[50,51,67,68], creating further threats to its validity in these studies. DES scores have been demonstrated to correlate with dissociative disorder diagnoses, but its subscales are not only not specific to dissociation but they also correlate with other psychopathology more broadly[69,70]. The MBI-HHS depersonalization subscale does not measure diagnostic constructs incorporated into depersonalization/derealization disorder.

A major problem with these dissociation measures is the potential for conflation of nonpathological experiences with the pathological components of dissociative disorders. Conceptually, many DES items elicit experiences that are common in general populations and reflect benign or everyday processes such as not remembering parts of conversations or complete absorption of attention in a television program or a movie, especially the items contained in the “imaginative absorption” subgroup comprising about half of its items[7]. For example, “missing part of a conversation” was endorsed by 83% of the general population in one study, and even “feeling as though one were two different people” was endorsed by nearly half[7]. Because the imaginative absorption subscale of the DES has been demonstrated to reflect nonpathological processes[7,71,72], the total dissociation score from this instrument includes a substantive amount of nonpathological material contributed by this subscale. To address this problem, a specifically pathological dissociative taxon was constructed from the DES items considered to be most pathological (and specifically not including any of the imaginative absorption subscale items)[73]. The DES taxon has been superior to the entire DES in correlating with dissociative diagnoses[72,74,75], but it has not been demonstrated to have the ability to classify or even identify dissociative disorders with reasonable accuracy[72,74]. No other dissociation scales have been systematically examined for their ability to differentiate diagnosable psychopathology from benign or nonpathological experiences.

Another problem with many dissociation measures (especially DES and MBI-HSS) is the lifetime collection of dissociative experiences that is far broader than the time frame of interest, i.e. the postdisaster period. Thus, much of the data collected with these instruments may pertain to predisaster periods only, which thus cannot reflect effects of the disaster ostensibly examined in these studies. In contrast, the PDEQ does focus on the acute postdisaster time frame and thus its data does have the potential to provide information relevant to effects of the disaster. However, the collection of PDEQ data months and even years after the disaster in many of these studies introduced potential recall bias through the fading of memory with time elapsed since the event.

Correct measurement of exposure is critical to the ability to determine if an outcome is related to the disaster. Disaster research requires special attention to trauma exposures, because of the conditional nature of the diagnostic construct of PTSD requiring a qualifying exposure to trauma to consider symptoms or a diagnosis to be disaster-related, and because psychosocial outcomes are highly linked to trauma exposures[76]. Trauma exposure data are also needed in studies of dissociation to determine associations with disaster to support assumptions of a causal role of disaster trauma in the development of dissociation. If it is unknown whether the sample was even exposed, it cannot be stated whether exposure to disaster leads to dissociation. Many of the reviewed studies enrolled samples without disaster trauma exposure or mixed trauma-unexposed and trauma-exposed survivors resulting in problems of sample heterogeneity. Many studies either did not specify disaster trauma exposure or mixed exposure groups without controlling for them in the analyses. Some studies did not differentiate exposure to disaster trauma from other disaster-related stressors. Many of the studies reviewed did not even compare exposures with outcomes.

Notwithstanding the many identified methodological problems in the studies of dissociation reviewed here, comparison of levels of dissociation in disaster-affected populations with dissociation in other populations provides a broader view of the occurrence of dissociation in different settings. A number of studies have used the DES to measure dissociation prevalence in general populations, disaster-affected populations, and treatment populations, allowing comparison of these populations using a consistent measure. General population studies using the DES have identified average dissociation scores of 7-11 (out of a possible 100)[7,77-79]. Studies of disaster survivors using the DES have found somewhat higher scores, 11-26[36,48,50,80]. Studies of patients with dissociative disorders using the DES have found even higher scores, 24-60 (for example[81-85]). Thus, disaster survivors in these studies seem to have observably greater dissociation than in general populations, but it does not rise to the far higher levels of dissociation patient populations.

The higher prevalence of dissociative findings in disaster survivor populations than in general populations could possibly relate to two possibilities: (1) that actual dissociative psychopathology generated by disaster exposure; or (2) that benign or nonpathological experiences generated by the extreme circumstances of disaster exposure generating detectable scores on dissociation measures. Considering the first possibility, if exposure to disaster trauma precipitates the development of dissociative disorders, then it is possible that the somewhat higher dissociative scores in these groups could reflect modest numbers of individuals with dissociative disorders. However, because none of the dissociative measures in the studies reviewed assessed the diagnostic criteria for dissociative disorders, it is impossible to know if new dissociative disorders follow disaster exposure. Considering the second possibility, the somewhat higher dissociative scores in disaster survivor populations than in general populations require careful interpretation. They could at least partially represent normative responses to disaster exposure that may not reflect pathological states. Again, because none of the dissociative measures in the studies reviewed assessed the diagnostic criteria for dissociative disorders, assumptions that the dissociation measured represents dissociative pathology may constitute a conflation of nonpathological responses with psychopathology.

The conflation of normative responses to disaster trauma with psychopathology may naturally arise from the extreme and unusual disaster circumstances promoting a sense of bizarreness and unreality akin to a dream, fantasy, or movie, because it is unlike other kinds of experience occurring in real waking life. Additionally, the focus of attention in disasters may be narrowed to the most important parts of the experience, preventing memories of some parts of the experience whose absence might be inadvertently interpreted as pathological amnesia rather than a natural consequence of constricted attention. All of these disaster experiences may be considered to be examples of the cognitive processes of the dissociative absorption and imagination factor, which Ross et al[7] and Merckelbach et al[86] have interpreted as nonpathological in modest amounts, such as in these studies of general populations and disaster survivors. To the extent that general populations register small but detectable scores of dissociation measures, they may have endemic levels of benign dissociative phenomena, and the higher scores in disaster survivors may reflect generation of more of these phenomena through extreme trauma exposure.

The still higher prevalence of reported dissociation in patients with dissociative disorders than in disaster survivors may relate to presence of the dissociative psychopathology that defines dissociative patient populations as well as to patient reporting styles[87]. In part, because all patients with dissociative disorders have dissociative disorders, their scores on dissociative measures would be expected to be higher than in other populations not selected for psychiatric illness, such as disaster-exposed groups. Again, however, because the dissociative measures in the disaster studies reviewed do not diagnose dissociative disorders, there is no information about the incidence of dissociative disorders following disaster exposure. Dissociative disorders are not listed among the classical responses to disasters[88], and even case reports of dissociative disorders in disaster survivors are very rare[89]. Thus, the association of new dissociative disorders with disaster exposure has not been demonstrated, much less causation of dissociative disorders by disaster exposure. Because a well-established characteristic of patients with dissociative disorders is a strong tendency to over-endorse symptoms[87], it is difficult to know to what degree the very high levels of dissociation in this population are an artifact of their symptom endorsement styles and how much of it truly reflects dissociative disorders.

Most of the disaster studies reviewed here compared dissociation with posttraumatic stress. Like the measures for dissociation, the posttraumatic stress measures used in these studies did not assess diagnostic criteria for PTSD, did not link symptoms to PTSD-qualifying trauma exposures, included individuals not exposed to disaster trauma, did not differentiate psychopathology from normative reactions, and did not necessarily capture material from the acute postdisaster time frame. Most of the studies comparing dissociation with posttraumatic stress reported significant associations between them. Because of the many serious limitations of both sets of measures and the presence of other methodological issues, the interpretation of this association may be tenuous[59], and even significant associations in bivariate analyses did not hold up in multivariate analyses and longitudinal assessment. The presence of an association between dissociation and posttraumatic stress might reflect well-known patterns of vulnerabilities to psychopathology broadly, as well as consistent effects of endorsement styles on both dissociative and posttraumatic stress measures. Even reviews[61,62] and meta-analyses[59,60,90] examining studies of associations of dissociation with PTSD more broadly do not find consistent associations between these two entities.

In the studies reviewed, dissociation was associated not only with posttraumatic stress, but with a wide range of other psychiatric disorders, symptoms, and negative emotional, cognitive, and functional states. There could be a number of reasons for such broad relationships and nonspecificity of associations with dissociation. This could represent measurement problems related to the known problems of nonspecificity of certain dissociation instruments as discussed above. It is possible that the phenomenon known as publication bias[91] or file drawer bias[92], in which studies with significant or positive findings have a much greater likelihood of being published, might have contributed to such broad associations with dissociation. Again, the apparent relationships of various disorders and negative states might occur as artifacts of consistent reporting biases within individuals across different measurements.

In summary, the body of literature on studies of dissociation in relation to disaster has emerged almost completely from studies not focused specifically on this purpose but rather to investigate the relationship of dissociation to other disaster outcomes. These studies uniformly contain unsurmountable methodological limitations such as reliance on nondiagnostic dissociation measures with threats to validity including conflation of nonpathological experiences with psychopathology, lack of temporal specificity to postdisaster time frames, and problems with disaster exposure issues pertaining to sampling, measurement, and analysis. Given this collection of methodological limitations in these studies, it cannot be concluded from this literature that dissociation is an established outcome of disaster. Of particular interest is the observation that no published articles, to the best of our knowledge, have presented dissociative disorders as identified outcomes of any disaster studied. If there is a relation of dissociative phenomena more broadly and the experience of disaster, it is unclear from the research conducted what these experiences represent in terms of negative mental health outcomes.

Methodologically rigorous research is needed to determine the prevalence of dissociative phenomena after disasters and their relationship to trauma exposure. Studies are needed that provide systematic diagnostic assessment of dissociative disorders such as structured interviews to formally establish the prevalence and incidence of established dissociative disorders after disasters. Nosological research is needed to further clarify the distinctions between benign or normative and pathological dissociative responses to disaster trauma exposure, such as by examining associations between observed dissociative phenomena and established indictors of psychopathology such as clinically significant distress, functional impairment, seeking treatment, and associations with other established psychopathology. Additionally, a long list of serious methodological limitations identified in the studies reviewed will need to be addressed in future research on dissociation and disaster trauma can move forward to provide data of sufficient quality to render empirically based conclusions.

The literature on dissociation in relation to disaster contains unsurmountable methodological limitations such as reliance on nondiagnostic dissociation measures, lack of temporal specificity to postdisaster time frames, and problems with disaster exposure issues pertaining to sampling, measurement, and analysis. It cannot be concluded from the research that dissociation is an established outcome of disasters.

Trauma has long been assumed to be causally associated with the development of dissociation. If trauma causes dissociation, then dissociation would be expected to emerge in disaster-exposed populations.

Although some studies have investigated dissociation in disaster survivors, no prior reviews have been published specifically on dissociation associated with disasters.

This review aimed to systematically evaluate existing studies on dissociation in disaster-exposed populations and to examine the relationship between dissociation and exposure to disaster.

A systematic search was performed using Embase, Medline, and PsychINFO databases to identify studies reporting on dissociative disorders or symptoms after disasters in adult or child disaster survivors and rescue/recovery workers. The search used the following key terms: “disaster*,” “dissociat*,” “multiple personality,” “fugue,” “psychogenic amnesia,” “derealization,” and “depersonalization”. Only studies in English and those with a sample size of 30 or more were considered. Studies of military conflicts and war were excluded.

The final review contained 53 articles, more than two-thirds (68%) reporting dissociation in adults, about one-tenth (9%) in children or adolescents, and about one-fourth (23%) in rescue/recovery workers, involving many different types of disasters. None of the included studies assessed or provided data on dissociative disorders; all used self-report symptom scales. Only two studies focused primarily on dissociation as a disaster outcome. Many of the samples had no disaster trauma exposures or only some members with exposures, and some studies did not differentiate exposure to disaster trauma from other disaster-related stressors. Most of the disaster studies compared dissociation with posttraumatic stress and did not find consistent associations between these two entities. A wide range of other psychiatric disorders, symptoms, and negative emotional, cognitive, and functional states were found to be associated with dissociation in disaster-exposed populations.

The existing body of research on dissociation as an outcome of disaster is fraught with serious methodological limitations in sampling, assessment of dissociation and other psychopathology, and unwarranted causal assumptions. The magnitude of these limitations precludes definitive conclusions regarding whether dissociation is an established outcome of disaster.

Methodologically rigorous research that provide systematic diagnostic assessment of dissociative disorders such as structured interviews is needed to determine the prevalence of dissociative phenomena after disasters and their relationship to trauma exposure. Further nosological research is needed to adequately differentiate between benign/normative and pathological dissociative responses to disaster trauma exposure. Also, important methodological limitations identified in the studies reviewed should be addressed in future research on the relationship of dissociation and disasters.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chakrabarti S, Wang YP S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association 2013; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | North CS. The Classification of Hysteria and Related Disorders: Historical and Phenomenological Considerations. Behav Sci (Basel). 2015;5:496-517. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van der Kolk BA, van der Hart O. Pierre Janet and the breakdown of adaptation in psychological trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:1530-1540. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 241] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Brown P, Macmillan MB, Meares R, Van der Hart O. Janet and Freud: revealing the roots of dynamic psychiatry. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1996;30:480-9; discussion 489-91. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Van der Hart O, Horst R. The dissociation theory of Pierre Janet. J Trauma Stress. 1989;2:397-412. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Butler LD. Normative dissociation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29:45-62, viii. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ross CA, Joshi S, Currie R. Dissociative experiences in the general population: a factor analysis. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1991;42:297-301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Seligman R, Kirmayer LJ. Dissociative experience and cultural neuroscience: narrative, metaphor and mechanism. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2008;32:31-64. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Spiegel D. Dissociating damage. Am J Clin Hypn. 1986;29:123-131. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 121] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dalenberg CJ, Brand BL, Gleaves DH, Dorahy MJ, Loewenstein RJ, Cardeña E, Frewen PA, Carlson EB, Spiegel D. Evaluation of the evidence for the trauma and fantasy models of dissociation. Psychol Bull. 2012;138:550-588. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 276] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dunstan FD, Nix ABJ. How Large is a Large Sample? Teach Stat. 1990;12:18-22. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47017] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43253] [Article Influence: 2883.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Giannakopoulos NN, Rammelsberg P, Eberhard L, Schmitter M. A new instrument for assessing the quality of studies on prevalence. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16:781-788. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Russell EJ, Fawcett JM, Mazmanian D. Risk of obsessive-compulsive disorder in pregnant and postpartum women: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:377-385. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, Baker P, Smith E, Buchbinder R. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:934-939. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1168] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1553] [Article Influence: 129.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Macaulay S, Dunger DB, Norris SA. Gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97871. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cardeña E, Spiegel D. Dissociative reactions to the San Francisco Bay Area earthquake of 1989. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:474-478. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 159] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Koopman C, Classen C, Spiegel D. Dissociative responses in the immediate aftermath of the Oakland/Berkeley firestorm. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9:521-540. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Marmar CR, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, Wilson JP and Keane TM. The peritraumatic dissociative experiences questionnaire. Wilson JP and Keane TM. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: The Guilford Press 1997; 144-168. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174:727-735. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Carlson EB, Putnam FW. An update on the dissociative experiences scale. Dissociation. 1993;6:16-27. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2:99-113. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | DeLisi LE, Maurizio A, Yost M, Papparozzi CF, Fulchino C, Katz CL, Altesman J, Biel M, Lee J, Stevens P. A survey of New Yorkers after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:780-783. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 98] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lawyer SR, Resnick HS, Galea S, Ahern J, Kilpatrick DG, Vlahov D. Predictors of peritraumatic reactions and PTSD following the September 11th terrorist attacks. Psychiatry. 2006;69:130-141. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Miron LR, Orcutt HK, Kumpula MJ. Differential predictors of transient stress versus posttraumatic stress disorder: evaluating risk following targeted mass violence. Behav Ther. 2014;45:791-805. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ozdemir O, Boysan M, Guzel Ozdemir P, Yilmaz E. Relationships between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dissociation, quality of life, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation among earthquake survivors. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228:598-605. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Özdemir O, Boysan M, Güzel Özdemir P, Yilmaz E. Relations between Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, Dissociation and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder among Earthquake Survivors. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2015;52:252-257. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Blanc J, Rahill GJ, Laconi S, Mouchenik Y. Religious Beliefs, PTSD, Depression and Resilience in Survivors of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:697-703. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Christiansen DM, Elklit A. Risk factors predict post-traumatic stress disorder differently in men and women. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2008;7:24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rosendal S, Salcioğlu E, Andersen HS, Mortensen EL. Exposure characteristics and peri-trauma emotional reactions during the 2004 tsunami in Southeast Asia--what predicts posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms? Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52:630-637. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | van der Velden PG, Kleber RJ, Christiaanse B, Gersons BP, Marcelissen FG, Drogendijk AN, Grievink L, Olff M, Meewisse ML. The independent predictive value of peritraumatic dissociation for postdisaster intrusions, avoidance reactions, and PTSD symptom severity: a 4-year prospective study. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:493-506. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hunt MG, Bogue K, Rohrbaugh N. Pet Ownership and Evacuation Prior to Hurricane Irene. Animals (Basel). 2012;2:529-539. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Laor N, Wolmer L, Kora M, Yucel D, Spirman S, Yazgan Y. Posttraumatic, dissociative and grief symptoms in Turkish children exposed to the 1999 earthquakes. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:824-832. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kadak MT, Nasıroğlu S, Boysan M, Aydın A. Risk factors predicting posttraumatic stress reactions in adolescents after 2011 Van earthquake. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54:982-990. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Piccardi L, Palmiero M, Nori R, Baralla F, Cordellieri P, D’Amico S, Giannini AM. Persistence of Traumatic Symptoms After Seven Years: Evidence from Young Individuals Exposed to the L’Aquila Earthquake. J Loss Trauma. 2017;22:487-500. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Simeon D, Greenberg J, Nelson D, Schmeidler J, Hollander E. Dissociation and posttraumatic stress 1 year after the World Trade Center disaster: follow-up of a longitudinal survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:231-237. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Captari LE, Hook JN, Mosher DK, Boan D, Aten JD, Davis EB, Davis DE, Van Tongeren DR. Negative Religious Coping and Burnout Among National Humanitarian Aid Workers Following Typhoon Haiyan. J Psychol Christ. 2018;37:28-41. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Biggs QM, Fullerton CS, Reeves JJ, Grieger TA, Reissman D, Ursano RJ. Acute stress disorder, depression, and tobacco use in disaster workers following 9/11. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:586-592. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Wang L. Acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in disaster or rescue workers. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1370-1376. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 268] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Duncan E, Dorahy MJ, Hanna D, Bagshaw S, Blampied N. Psychological responses after a major, fatal earthquake: the effect of peritraumatic dissociation and posttraumatic stress symptoms on anxiety and depression. J Trauma Dissociation. 2013;14:501-518. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Graham RA, Osofsky JD, Osofsky HJ, Hansel TC. School based post disaster mental health services: decreased trauma symptoms in youth with multiple traumas. Adv Sch Ment Health Promot. 2017;10:161-175. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Elklit A, Christiansen DM. Predictive factors for somatization in a trauma sample. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5:1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Fujitani K, Carroll M, Yanagisawa R, Katz C. Burnout and Psychiatric Distress in Local Caregivers Two Years After the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima Nuclear Radiation Disaster. Community Ment Health J. 2016;52:39-45. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Grieger TA, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol use, and perceived safety after the terrorist attack on the pentagon. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1380-1382. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 82] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | van der Velden PG, Kleber RJ, Koenen KC. Smoking predicts posttraumatic stress symptoms among rescue workers: a prospective study of ambulance personnel involved in the Enschede Fireworks Disaster. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94:267-271. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Reeves J, Shigemura J, Grieger T. Perceived safety in disaster workers following 9/11. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:61-63. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Su YJ. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and depressive symptoms among burn survivors two years after the 2015 Formosa Fun Coast Water Park explosion in Taiwan. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2018;9:1512263. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Craparo G, Gori A, Mazzola E, Petruccelli I, Pellerone M, Rotondo G. Posttraumatic stress symptoms, dissociation, and alexithymia in an Italian sample of flood victims. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:2281-2284. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Mattei A, Fiasca F, Mazzei M, Abbossida V, Bianchini V. Burnout among healthcare workers at L'Aquila: its prevalence and associated factors. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22:1262-1270. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Buskila D, Ablin JN, Ben-Zion I, Muntanu D, Shalev A, Sarzi-Puttini P, Cohen H. A painful train of events: increased prevalence of fibromyalgia in survivors of a major train crash. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:S79-S85. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Komarovskaya I, Brown AD, Galatzer-Levy IR, Madan A, Henn-Haase C, Teater J, Clarke BH, Marmar CR, Chemtob CM. Early physical victimization is a risk factor for posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among Mississippi police and firefighter first responders to Hurricane Katrina. Psychol Trauma. 2014;6:92-96. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Bromet EJ, Atwoli L, Kawakami N, Navarro-Mateu F, Piotrowski P, King AJ, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Bunting B, Demyttenaere K, Florescu S, de Girolamo G, Gluzman S, Haro JM, de Jonge P, Karam EG, Lee S, Kovess-Masfety V, Medina-Mora ME, Mneimneh Z, Pennell BE, Posada-Villa J, Salmerón D, Takeshima T, Kessler RC. Post-traumatic stress disorder associated with natural and human-made disasters in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol Med. 2017;47:227-241. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiol Rev. 2005;27:78-91. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 760] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 645] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | North CS. Current research and recent breakthroughs on the mental health effects of disasters. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16:481. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 108] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | North CS, Pfefferbaum B. Mental health response to community disasters: a systematic review. JAMA. 2013;310:507-518. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 273] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Hopwood TL, Schutte NS. Psychological outcomes in reaction to media exposure to disasters and large-scale violence: A meta-analysis. Psychol Violence. 2017;7:316. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 57. | Parker G, Lie D, Siskind DJ, Martin-Khan M, Raphael B, Crompton D, Kisely S. Mental health implications for older adults after natural disasters--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28:11-20. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Sweileh WM. A bibliometric analysis of health-related literature on natural disasters from 1900 to 2017. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17:18. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Lensvelt-Mulders G, van der Hart O, van Ochten JM, van Son MJ, Steele K, Breeman L. Relations among peritraumatic dissociation and posttraumatic stress: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:1138-1151. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 92] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:52-73. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | van der Hart O, van Ochten JM, van Son MJ, Steele K, Lensvelt-Mulders G. Relations among peritraumatic dissociation and posttraumatic stress: a critical review. J Trauma Dissociation. 2008;9:481-505. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | van der Velden PG, Wittmann L. The independent predictive value of peritraumatic dissociation for PTSD symptomatology after type I trauma: a systematic review of prospective studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:1009-1020. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Brooks R, Bryant RA, Silove D, Creamer M, O'Donnell M, McFarlane AC, Marmar CR. The latent structure of the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:153-157. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Carvalho T, Cunha M, Pinto-Gouveia J, da Motta C. Model comparison and structural invariance of the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire in Portuguese colonial war veterans. Traumatology. 2018;24:62. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Lee SH, Kim EJ, Noh JW, Chae JH. Factors Associated with Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms in Students Who Survived 20 Months after the Sewol Ferry Disaster in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33:e90. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Pietrzak RH, Southwick SM, Tracy M, Galea S, Norris FH. Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and perceived needs for psychological care in older persons affected by Hurricane Ike. J Affect Disord. 2012;138:96-103. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Marmar CR, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, Delucchi KL, Best SR, Wentworth KA. Longitudinal course and predictors of continuing distress following critical incident exposure in emergency services personnel. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:15-22. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 68. | Marmar CR, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, Ronfeldt HM, Foreman C. Stress responses of emergency services personnel to the Loma Prieta earthquake Interstate 880 freeway collapse and control traumatic incidents. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9:63-85. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Gleaves DH, Williams TL, Harrison K, Cororve MB. Measuring dissociative experiences in a college population: A study of convergent and discriminant validity. J Trauma Dissociation. 2000;1:43-57. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 70. | Van Ijzendoorn MH, Schuengel C. The measurement of dissociation in normal and clinical populations: Meta-analytic validation of the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES). Clin Psychol Rev. 1996;16:365-382. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 388] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Giesbrecht T, Merckelbach H, Geraerts E. The dissociative experiences taxon is related to fantasy proneness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:769-772. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Leavitt F. Dissociative Experiences Scale Taxon and measurement of dissociative pathology: Does the taxon add to an understanding of dissociation and its associated pathologies? J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 1999;6:427-440. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 73. | Waller N, Putnam FW, Carlson EB. Types of dissociation and dissociative types: A taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:300-321. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 74. | Modestin J, Erni T. Testing the dissociative taxon. Psychiatry Res. 2004;126:77-82. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Simeon D, Knutelska M, Nelson D, Guralnik O, Schmeidler J. Examination of the pathological dissociation taxon in depersonalization disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191:738-744. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | North CS, Pollio DE, Smith RP, King RV, Pandya A, Surís AM, Hong BA, Dean DJ, Wallace NE, Herman DB, Conover S, Susser E, Pfefferbaum B. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among employees of New York City companies affected by the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011;5 Suppl 2:S205-S213. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Akyüz G, Doğan O, Sar V, Yargiç LI, Tutkun H. Frequency of dissociative identity disorder in the general population in Turkey. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40:151-159. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Levin R, Spei E. Relationship of purported measures of pathological and nonpathological dissociation to self-reported psychological distress and fantasy immersion. Assessment. 2004;11:160-168. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Maaranen P, Tanskanen A, Honkalampi K, Haatainen K, Hintikka J, Viinamäki H. Factors associated with pathological dissociation in the general population. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:387-394. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Nobakht HN, Ojagh FS, Dale KY. Risk factors of post-traumatic stress among survivors of the 2017 Iran earthquake: The importance of peritraumatic dissociation. Psychiatry Res. 2019;271:702-707. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Carlson EB, Putnam FW, Ross CA, Torem M, Coons P, Dill DL, Loewenstein RJ, Braun BG. Validity of the Dissociative Experiences Scale in screening for multiple personality disorder: a multicenter study. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1030-1036. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 298] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Latz TT, Kramer SI, Hughes DL. Multiple personality disorder among female inpatients in a state hospital. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1343-1348. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Saxe GN, van der Kolk BA, Berkowitz R, Chinman G, Hall K, Lieberg G, Schwartz J. Dissociative disorders in psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1037-1042. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 175] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Simeon D, Hwu R, Knutelska M. Temporal disintegration in depersonalization disorder. J Trauma Dissociation. 2007;8:11-24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Tutkun H, Sar V, Yargiç LI, Ozpulat T, Yanik M, Kiziltan E. Frequency of dissociative disorders among psychiatric inpatients in a Turkish University Clinic. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:800-805. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Merckelbach H, Muris P, Rassin E. Fantasy proneness and cognitive failures as correlates of dissociative experiences. Pers Individ Dif. 1999;26:961-967. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Merckelbach H, Boskovic I, Pesy D, Dalsklev M, Lynn SJ. Symptom overreporting and dissociative experiences: A qualitative review. Conscious Cogn. 2017;49:132-144. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Gaon A, Kaplan Z, Dwolatzky T, Perry Z, Witztum E. Dissociative symptoms as a consequence of traumatic experiences: the long-term effects of childhood sexual abuse. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2013;50:17-23. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 89. | Odagaki Y. A Case of Persistent Generalized Retrograde Autobiographical Amnesia Subsequent to the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2017;2017:5173605. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Breh DC, Seidler GH. Is peritraumatic dissociation a risk factor for PTSD? J Trauma Dissociation. 2007;8:53-69. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337:867-872. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2020] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1925] [Article Influence: 58.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Franco A, Malhotra N, Simonovits G. Social science. Publication bias in the social sciences: unlocking the file drawer. Science. 2014;345:1502-1505. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 653] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 381] [Article Influence: 38.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Arnberg FK, Eriksson NG, Hultman CM, Lundin T. Traumatic bereavement, acute dissociation, and posttraumatic stress: 14 years after the MS Estonia disaster. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24:183-190. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Eriksson NG, Lundin T. Early traumatic stress reactions among Swedish survivors of the m/s Estonia disaster. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169:713-716. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Birmes PJ, Brunet A, Coppin-Calmes D, Arbus C, Coppin D, Charlet JP, Vinnemann N, Juchet H, Lauque D, Schmitt L. Symptoms of peritraumatic and acute traumatic stress among victims of an industrial disaster. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:93-95. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Birmes PJ, Daubisse L, Brunet A. Predictors of enduring PTSD after an industrial disaster. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:116. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Bui E, Tremblay L, Brunet A, Rodgers R, Jehel L, Véry E, Schmitt L, Vautier S, Birmes P. Course of posttraumatic stress symptoms over the 5 years following an industrial disaster: a structural equation modeling study. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:759-766. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | De Soir E, Zech E, Versporten A, Van Oyen H, Kleber R, Mylle J, van der Hart O. Degree of exposure and peritraumatic dissociation as determinants of PTSD symptoms in the aftermath of the Ghislenghien gas explosion. Arch Public Health. 2015;73:21. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Hagenaars MA, van Minnen A, Hoogduin KA. Peritraumatic psychological and somatoform dissociation in predicting PTSD symptoms: a prospective study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:952-954. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Hunt M, Al-Awadi H, Johnson M. Psychological sequelae of pet loss following Hurricane Katrina. Anthrozoos. 2008;21:109-121. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 101. | Kannis‐Dymand L, Carter JD, Lane BR, Innes P. The relationship of peritraumatic distress and dissociation with beliefs about memory following natural disasters. Aust Psychol. 2018;. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Koopman C, Classen C, Spiegel D. Predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms among survivors of the Oakland/Berkeley, Calif., firestorm. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:888-894. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 327] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Merrell H. Dissociation Differences Between Human-made Trauma and Natural Disaster Trauma, Thesis. George Fox University 2013. Available from: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/psyd/126. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 104. | Pietrzak RH, Van Ness PH, Fried TR, Galea S, Norris FH. Trajectories of posttraumatic stress symptomatology in older persons affected by a large-magnitude disaster. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:520-526. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Simeon D, Greenberg J, Knutelska M, Schmeidler J, Hollander E. Peritraumatic reactions associated with the World Trade Center disaster. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1702-1705. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |