Published online Jan 19, 2022. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v12.i1.117

Peer-review started: February 27, 2021

First decision: October 17, 2021

Revised: October 25, 2021

Accepted: November 29, 2021

Article in press: November 29, 2021

Published online: January 19, 2022

The accelerated population growth of the elderly (individuals aged 60 years or more) across the globe has many indications, including changes in demography, health, the psycho-social milieu, and economic security. This transition has given rise to varied challenges; significant changes have been observed in regard to developing strategies for health care systems across the globe. The World Health Organization (WHO) is also engaging in initiatives and mediating processes. Furthermore, advocacy is being conducted regarding a shift toward the salutogenic model from the pathogenic model. The concept behind this move was to shift from disablement to enablement and from illness to wellness, with the notion of mental health promotion (MHP) being promoted. This article attempts to discuss the MHP of elderly individuals, with special reference to the need to disseminate knowledge and awareness in the community by utilizing the resources of the health sector available in the WHO South-East Asia Region countries. We have tried to present the current knowledge gap by exploring the existing infrastructure, human resources, and financial resources. There is much to do to promote the mental health of the elderly, but inadequate facilities are available. Based on available resources, a roadmap for MHP in elderly individuals is discussed.

Core Tip: In gross domestic product South-East Asia Region Organization (SEARO) countries, the aging population is increasing exponentially; with this increment, mental health issues and care needs are increasing drastically. The mental health promotion of elderly people needs adequate awareness, enough human resources and infrastructure, good psychosocial support, the use of innovations in care, research, and reasonable funding. The mental health care needs of the elderly in SEARO countries are tremen

- Citation: Pandey NM, Tripathi RK, Kar SK, Vidya KL, Singh N. Mental health promotion for elderly populations in World Health Organization South-East Asia Region: Needs and resource gaps. World J Psychiatry 2022; 12(1): 117-127

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v12/i1/117.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i1.117

The global population is aging, and life expectancy is following an increasing trend. With an increased global growth rate of the elderly population (aged 60 years and older), the mental health issues of this group need thoughtful attention. The enormous mental health morbidity in this population group gives rise to a higher number of consumers of mental health care services. Thus, mental health care needs are also increasing. As per the World Health Organization (WHO) report, the global elderly population is expected to double by 2050 from the baseline level reported in 2015[1]. It is likely that by 2050, four out of every five elderly individuals will be located in low- and middle-income countries[1]. By 2019, the number of people in the world who were older than 60 years was reportedly 1 billion; this number is expected to increase to 1.4 billion by 2030 and 2.1 billion by 2050[2]. As the number of elderly individuals in the South-East Asia Region Organization (SEARO) is increasing rapidly, their mental health care needs will also increase significantly in the days to come.

Health promotion refers to the process that empowers a person to improve his or her strengths to retain health[3]. In contrast, MHP advocates maintaining one’s psychological well-being by adopting a scheduled routine, lifestyle, and a helpful environ

The WHO's document entitled "Decade of Healthy Aging 2021−2030" discusses the concept of healthy aging and emphasizes enhancing the functional abilities of the elderly population to promote healthy aging[7]. This document also discusses the vision for healthy aging by 2030 and appeals to the government and various other stakeholders to invest in and monitor healthy aging among the general population in the community[7]. The global strategy and action plan for aging and health (2016–2020) emphasizes the long and healthy life of every elderly population in the world[8]. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted by the United Nations member states, emphasize the good health and well-being of every individual, including those who are elderly[9].

Including 11 member states (Bangladesh, Bhutan, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, India, Indonesia, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Timor-Leste), the SEARO is one of the most heavily populated regions of the world[10]. The WHO SEARO caters to nearly one-fourth of the global population and is primarily affected by war, terrorism, political crisis, natural calamities, unemployment, and poverty[10]. The training for and teaching about geriatric mental health in the medical curriculum in South-East Asia are also inadequate, which affects the care of the elderly population[11]. Another major challenge of developing countries is that a large chunk of the geriatric population seeks help from nonqualified persons and traditional healers for their mental ailments[11]. Many South Asian countries, such as Japan, Singapore, China, Malaysia, and Thailand, have undertaken initiatives to develop country-specific policies to protect the rights of the elderly population and provide them with quality care[12]. The Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India, also developed a national policy for older persons in 1999, which was subsequently amended as per the needs of the elderly population[13].

The significant bulk of the population in the SEARO resides in India. In India, the elderly population comprises approximately 104 million individuals, which corresponds to 9% of the nation's total population[14]. It has been projected that by 2026, the elderly population (> 60 years) will rise to 14% of the total population, and by 2050, it is expected to be 19% of the total population[14].

Older adults globally face several challenges in regard to their deteriorating general physical health and increased risk of mental health issues, including neurocognitive disorders, loss of job, grief, loneliness, isolation, and abuse[14,15]. All these challenges compromise the quality of life of an individual. Commonly encountered mental health issues in the elderly are depression, other mood disorders and neurocognitive disorders[15-17]. Elderly populations are also victims of negatively expressed emotions[15].

There is a lack of resources and infrastructure for the care of the elderly population[18], which is evident in almost all WHO SEARO regions. In regard to the mental health care of the geriatric population, there are even fewer facilities[18]; the same/worse scenario is found everywhere in WHO SEARO countries. Generally, the geriatric population receives health care facilities from the general health care system, alternative medicine, home-based care, and other resources. Unfortunately, a more significant proportion of older adults are deprived of timely care for their health ailments[15].

Existing shreds of evidence suggest a massive burden of mental health issues among the elderly population. However, in low-income countries, resource scarcity is more serious and affects the geriatric population's mental health care[19]. In South-East Asia, several countries fall into the group of low-income countries, and their health care systems struggle with the scarcity of human resources and infrastructure. It has also been reported that the prevailing infrastructure necessary to meet mental health care needs among the elderly is sparse in India[20]. As a result of this vast gap in health care delivery, the existing health care sectors are overburdened, and older adults in need of help are deprived of care. A significant chunk of people with dementia live in developing countries. It is expected that by 2040, the exponential growth of people living with dementia in South-East Asian countries will exceed 300% of the baseline figure reported in 2001[19]. It has also been reported that loneliness is commonly seen among 3/4th of older adults suffering from depression[20]. Further

Another challenge found in developing countries is the lack or poor implementation of policies and programs that facilitate the care and protection of the elderly[21]. However, some countries lack specified indicators or targets against which the implementation of these policies/programs could be monitored, and some places hardly have any existing programs. Resources in terms of budgetary allocations and physical and human infrastructure are also questionable in some WHO SEARO countries. Such problems may be resolved by promoting the mental health of the elderly population, which attempts to sustain the psychological well-being of elderly individuals by committed efforts, for which an in-depth need availability vis. a vis. gap analysis in terms of various domains, such as housing, safety, security, financial, psychosocial, emotional, health, and other ancillary needs, would be required. This article attempts to discuss the various dimensions of MHP for the aging population in WHO SEARO countries in view of the available mental health resources, needs, and existing gaps.

We aimed to accomplish this review with a broad focus on MHP, including general and specific questions that are suitable for a comprehensive analysis of the subject. We aimed to conduct this review research in view of our own experiences and the existing literature on the topic to explore the needs, available resources, and gaps. This led us to provide a roadmap for further developments in the field of MHP in elderly individuals. The review was conducted in a phasewise manner.

Stage 1-Preparatory phase: First, the corresponding author approached four mental health professionals with experience in the field and discussed writing the manuscript. After obtaining consent from each participating author, we performed two subsequent meetings. Subsequently, the following research questions were identified: what are the mental health issues of the elderly population in general, and generally, how are they handled? What is needed for the better mental health of the elderly population? What services are available to balance the mental health and well-being of the elderly population? What health promotion strategies exist to maintain the mental health of the elderly population? The discussion led to identifying our research topic. With consensus, the topic was finalized as "Mental health promotion for the aging population in WHO SEARO countries: Needs and resource gaps." After identifying our review topic and question, we discussed the aim and objectives and finalized them. Then, decisions were made regarding strings to search the literature, time, and language.

Stage 2-Identification of related articles: With the help of keywords—mental health, promotion, and (older adults or Geriatrics or elderly)—two of the authors (VKL and NS) started including manuscripts (original and review) initially with the help of PubMed. A total of 195 articles were extracted from PubMed; of these, only six articles were suitable. Then, using an exact keyword search of articles, PubMed Central (PMC) was utilized. PMC revealed 51322 articles, and exploring articles from this huge bulk in a limited period was difficult; thus, the string was changed to MHP AND elderly OR Older adults AND WHO SEAR, which revealed 327 articles. Of these, only one article was found to be relevant. The selection of articles was limited to peer-reviewed and pragmatic research related to the goal of our study to make an evidence-based foundation to understand the MHP status in WHO SEARO countries.

Furthermore, as per the document's significance, a decision was made to include supplementary data from other sources. Documentation of the essential details was also performed simultaneously. The primary focus was on MHP, existing MHP programs, and related stakeholders. We tried to include almost all the articles and references with relevant documentation to avoid missing any related information obtained from the subsequent supplementary search.

MHP needs: The WHO states that the basic tenet of MHP for the elderly population is active and healthy aging itself[22]. Peace, shelter, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resources, equity, and social justice are prerequisites for health. Health promotion is not just the health sector's responsibility; rather, it goes beyond healthy lifestyles to well-being[23]. With advancing age, few specific issues affect mental health, such as physical ailments, financial insecurity, and inadequate social support[24]. Promoting mental health in the elderly population depends on helping them meet these specific needs, such as financial security, adequate housing, social support, general health care, and protection against ageism and abuse[22]. Some of these needs are universal and address the whole population, while others are selected and as indicated, target those with significant risks[25]. Promoting general health, preventing disease, and managing chronic illnesses go a long way in promoting the mental health of the elderly population. Therefore, training all health providers in working with issues and disorders related to aging is essential. Effective, community-level primary mental health care for older people is crucial. Health care training, education, and support to the caregivers must be provided[22].

The WHO considers the scope for interventions that address the risk factors for poor health and modify unhealthy behaviors and functional status to promote the health of the elderly population in general. Strategies have been recommended in the manual for primary care physicians under Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) [26]. Apart from this, the WHO has also provided recommendations, strategies, and support to member states/government agencies at the global level under different comprehensive action plans, including health promotion in general and specific strategies for promoting mental health.

Resources available for MHP: To understand the needs of MHP, the overall resource gaps and the ways to mitigate them, it is necessary first to have a general overview of the available mental health resources available in all eleven SEARO countries.

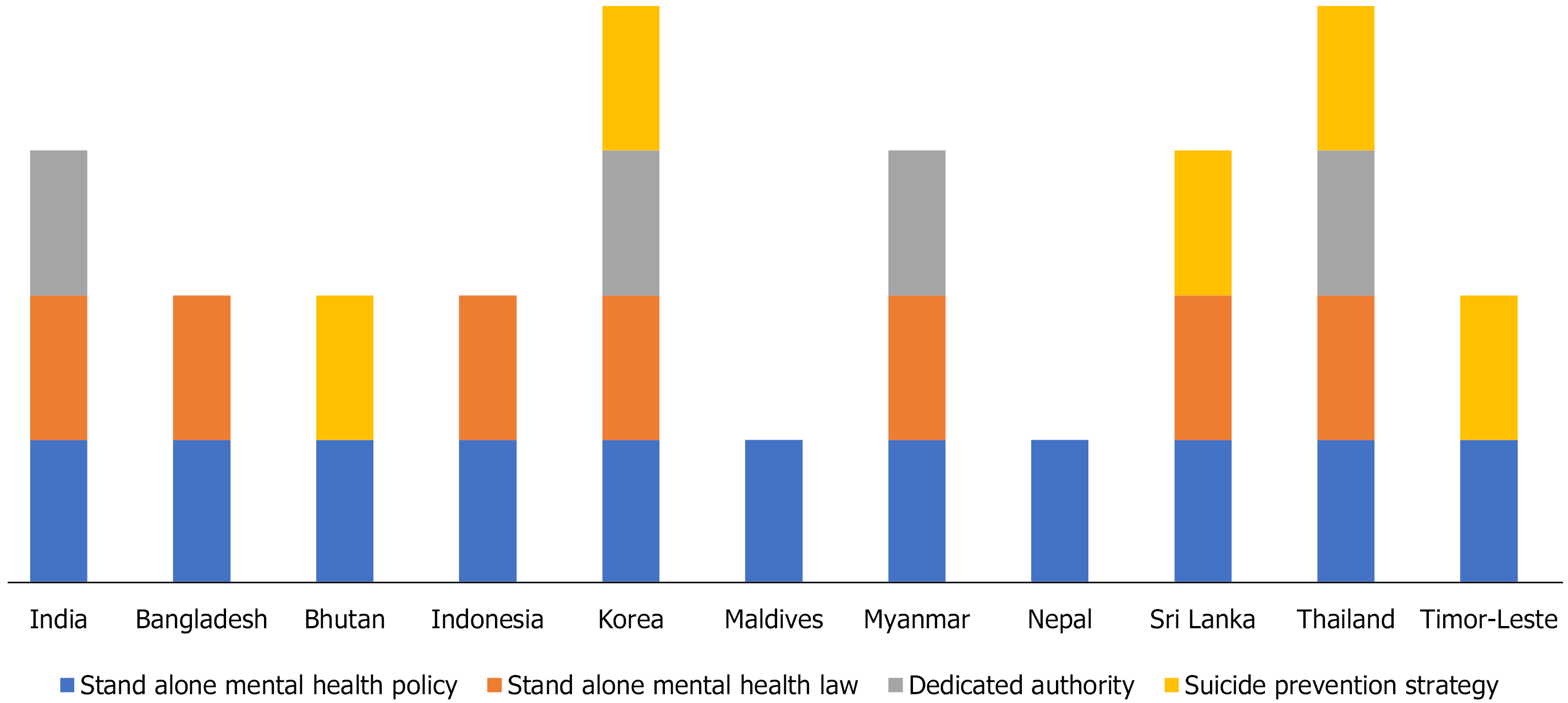

Table 1 depicts the availability of facilities in terms of policy, plan, legislation, and budgetary allocations[27]. The table is generated based on the Mental Health Atlas of 2017 and information available about the SDGs of SEARO countries[27-38]. Table 1 reveals that except for the Maldives and Nepal, most countries spend 5% or less of their total gross domestic product (GDP).

| Mental health policies and implementations | India | Bangladesh | Bhutan | Indonesia | Korea | Maldives | Myanmar | Nepal | Sri Lanka | Thailand | Timor-leste |

| Current health expenditure as share of GDP | 3.6% | 2.4% | 3.5% | 3.1% | Not found | 10.6% | 5.1% | 6.3% | 4.2% | 3.7% | 2.4% |

| Domestic general government health expenditure | 3.1 | 3.4 | 8.3 | 8.3 | - | 20.2 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 8.6 | 15.3 | 3.2 |

| Health worker density (per 10000 population) | 27.5 | 8.3 | 19.3 | 24.4 | 81 | 50 | 17.9 | 33.5 | 31.7 | 38.15 | 25.04 |

| Stand-alone policy or plan for mental health | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| The mental health policy/plan | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Policy/plan in line with human rights covenants | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Stand-alone law for mental health | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Dedicated authority or independent body assessing the compliance | Yes | No | No | Not found | Yes | Not found | Nonfunctional | Not found | Not found | Irregular and partial | Not found |

| Law is in line with human rights covenants | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 3 | Not found | Not found | Not found | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Existence of at least two functioning programs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not found | Yes | Not found | Not found | Not found | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Existence of a suicide prevention strategy | No | No | Yes | Not found | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Total mental health expenditure/-person (reported currency) | 4 INR | 2.4 BDT (2.0 INR) | 6.73 BTN (6.73 INR) | Not found | 76370.40 KRW (5014 INR) | Not found | 58.92 MMK (3 INR) | Not found | Not found | 46.48 THB (112.4 INR) | Not found |

| The government’s expenditure on mental health as % of total health expenditure | 1.30% | 0.50% | 0.30% | 6.00% | 3.80% | Not found | 0.36% | Not found | Not found | 0.30% | Not found |

Table 1 and Figure 1 also indicate that mental health policies or plans containing specified indicators or targets against which the implementation of these plans and policies can be monitored are present in most nations but not implemented in Bangladesh, the Maldives, and Sri Lanka. However, the stand-alone law for mental health is available in all SEAR countries except Bhutan, the Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, and Timor-Leste. However, a dedicated authority or independent body to assess the compliance of mental health legislation with international human rights exists only in India, Korea, and Thailand. This also provides the periodic inspections of facilities and the partial enforcement of mental health legislation (Table 1 and Figure 1). Regarding the financial aspects, the government's total expenditure on mental health as a % of the total government health expenditure is also below par in most SEARO nations, ranging from as low as 0.30% in Thailand to 1.50% in India and 6% in Indonesia. The WHO recommends that the mental health budget accounts for 5%–15 % of a country’s health care expenditures (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the mental health human resources (rate per 100000 population) of the SEARO countries[27]. The total mental health workers per 100000 population ranged from as low as 0.64 in Bhutan to 14.36 in Thailand, but the number of psychiatrists available per 1 Lakh population in all SEARO countries showed alarming data of even less than one, except in Korea and the Maldives, where it was 5.79 and 2.39, respectively. Additionally, among the psychiatrists available, those trained to deal appropriately with the complexities of geriatric mental health are scarce.

| Mental health human resources1 (per 100000 population) | India | Bangladesh | Bhutan | Indonesia | Korea | Maldives | Myanmar | Nepal | Sri Lanka | Thailand | Timor-leste |

| Total number of mental health professionals (government and non government) | 25312 | 1893 | 5 | 7751 | 20301 | 27 | 627 | 413 | 1480 | 9436 | 45 |

| Total mental health workers | 1.93 | 1.17 | 0.64 | 3.00 | 40.13 | 6.45 | 1.20 | 1.44 | 7.14 | 14.36 | 3.63 |

| Psychiatrists | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 5.79 | 2.39 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.52 | 0.99 | 0.08 |

| Child psychiatrists | 0 | 0 | Not found | Not found | 0.38 | Not found | Not found | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.24 |

| Geriatric psychiatrists | 24 | Hardly available | |||||||||

| Other specialist doctors | 0.15 | 0.01 | Not found | Not found | Not found | Not found | Not found | Not found | 1.47 | 1.24 | Not found |

| Mental health nurses | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.13 | 2.52 | 13.66 | Not found | 0.32 | 0.56 | 3.28 | 6.74 | 1.37 |

| Psychologists | 0.07 | 0.12 | Not found | 0.17 | 1.59 | 2.15 | 0 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.08 |

| Social workers | 0.06 | 0 | Not found | Not found | 8.40 | 0.48 | 0.01 | Not found | 0.28 | 0.91 | 1.61 |

| Occupational therapists | 0.03 | 0 | Not found | Not found | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0 | Not found | 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.16 |

| Speech therapists | 0.17 | 0 | Not found | Not found | Not found | 1.20 | Not found | Not found | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.08 |

| Other paid mental health workers | 0.36 | 0.03 | Not found | Not found | 10.21 | Not found | 0.47 | Not found | 1.04 | 1893.45 | Not found |

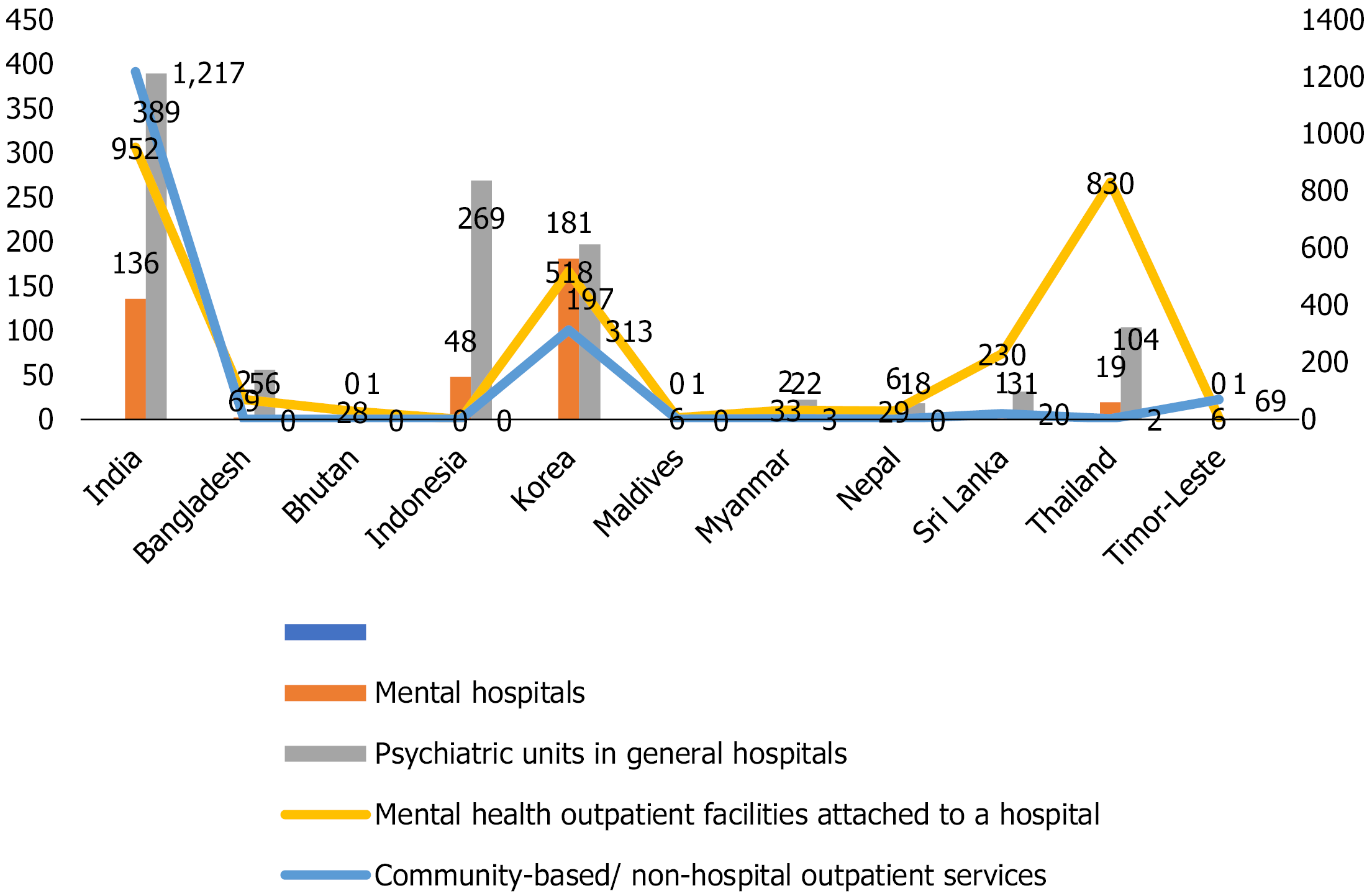

Table 3 shows the availability of physical infrastructure and its uptake in SEARO nations[27]. The outpatient facilities attached to a hospital and community-based/nonhospital mental health outpatient available are not on par per the population of these respective nations. It is also alarming that countries such as Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal have such a considerable scarcity of mental hospitals. Table 3 shows that MHP and prevention strategies are not functional. Data regarding the existence of at least two functioning programs are not available for Indonesia, Myanmar, and Nepal.

| Mental health infrastructure | India | Bangladesh | Bhutan | Indonesia | Korea | Maldives | Myanmar | Nepal | Sri Lanka | Thailand | Timorleste |

| Mental hospitals | 136 | 2 | Not found | 48 | 181 | Not found | 2 | 6 | 1 | 19 | Not found |

| Psychiatric units in general hospitals | 389 | 56 | 1 | 269 | 197 | 1 | 22 | 18 | 31 | 104 | 1 |

| Mental health outpatient facilities attached to a hospital | 952 | 69 | 28 | Not found | 518 | 6 | 33 | 29 | 230 | 830 | 6 |

| Private practitioners | 1217 | Not found | Not found | Not found | 313 | Not found | 3 | Not found | 20 | 2 | 69 |

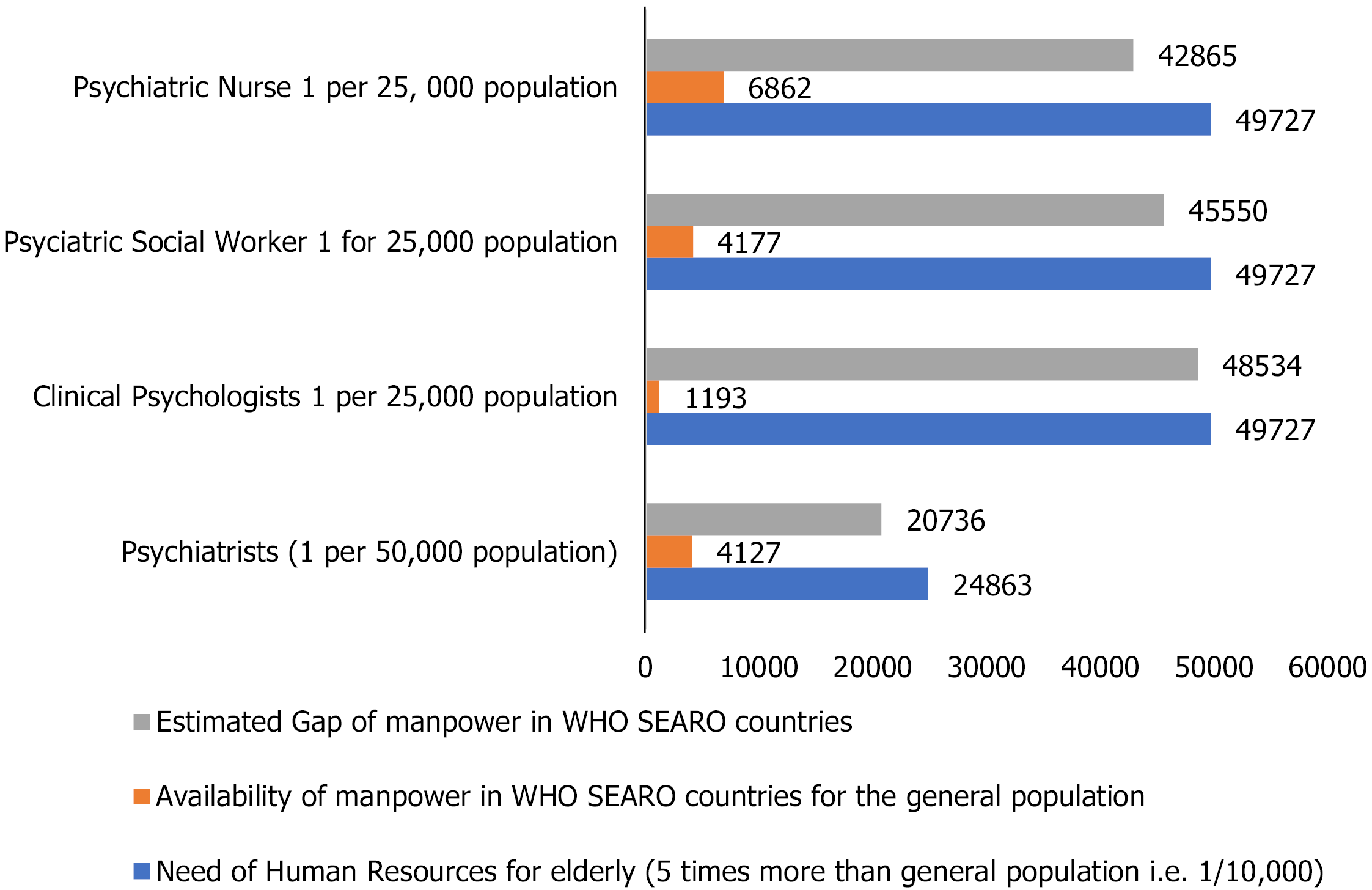

The gap: Table 4 and Figures 2, 3.

| Human resources requirement norms for the general population[37] | Human resources requirement for total population of WHO SEARO countries on Feburary 18, 2021(2537079071)a | Human resources requirement for elderly population 248633749b (@ 9.8%-WHO) SEARO countries as per norms of general population | Older adults with mental health problems @ 20% (tiwari and pandey, 2012) in SEARO 49726750 population as per general population norms | Availability of manpower in WHO SEARO countries | The gap (requirement -availability) |

| Psychiatrists (1 per 50000 population) | 50741.6 | 4972.7 | (4972.7 × 5) 24863.5 | 994.5 × 5 = 4972.5 | 9945.2 |

| Clinical psychologists 1 per 25000 population | 10148316 | 9945.3 | (9945.3 × 5) 49726.5 | 1989.7 × 5 = 9948.5 | 19893.8 |

| Psychiatric social workers 1 for 25000 population | 10148316 | 9945.3 | (9945.3 × 5) 49726.5 | 1989.7 × 5 = 9948.5 | 19893.8 |

| Psychiatric nurses 1 per 25 000 population | 10148316 | 9945.3 | (9945.3 × 5) 49726.5 | 1989.7 × 5 = 9948.5 | 19893.8 |

The objective of MHP comprises those activities that can enhance one's psychological well-being. To improve the elderly population's psychological well-being, we need to have inclusive legislation, proper mental health services in terms of physical and human infrastructure, social and financial security, and an elderly individual-friendly environment. We have tried to search for such exclusively available resources, but there are hardly any in existence. Thus, we have considered overall the available facilities for mental health care and other services. The recommendations gap for overall human resources are estimated based on the available literature[18,39].

The WHO recommendations for the ICOPE: To accomplish the MHP activities of the elderly, we have to look into the recommendations made by the WHO. These recom

Nutrition and dietary advice: Although the requirement for energy declines with age, due to diminishing sensory faculties such as taste and smell and dental issues, the elderly population is at risk for malnutrition. Adequate protein and limited salt intake are recommended, and foods with antioxidant properties such as green, yellow, and orange vegetables and fruits are recommended. The typical nutritional deficiencies are iron, fiber, folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin D, vitamin B12, calcium, zinc, riboflavin, and vitamin A[40]. The intake of calcium and vitamin D found in milk, curds, cheese, small fish, and certain green vegetables is advised. Exposure to sunlight is necessary to make the skin produce vitamin D. The routine prescription of multivitamins to be avoided, but vegetarians require vitamin B12 supplementation[40]. These findings have implications for physical well-being, specifically in terms of preventing cognitive decline and maintaining mood. Further, older adults need proper and suitable remedies for their health and psychological wellbeing within their limits, which is hard to approach in low and middle-income countries[41].

Exercise: Compared to older individuals who exercise and those who do not, the former have better physical health and better cognitive functioning. Older people should perform at least 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week. When older people cannot perform the recommended amount of physical activity due to their health condition, they should be as physically active as their abilities and conditions allow[42]. A lower frequency of vigorous physical activity is significantly associated with higher rates of diagnosed depression in the elderly population[43].

Social support and interaction: Social networks and interactions help promote older people's mental health and prevent mental illness. Social support to promote health must provide a sense of belonging and intimacy. It also helps people be more competent and self-efficacious[43].

Prevention of substance abuse: Chewing tobacco is a common practice among the elderly in the South-East Asian region, as is smoking. The intake of alcohol is also prevalent. Apart from these issues, benzodiazepine abuse is also common, which adds to cognitive and mood deterioration in the long term[24]. Managing these conditions would work as a mental health-promoting strategy by reducing the risk of cognitive decline and mood dysregulation[40].

Prevention of polypharmacy: Polypharmacy increases cognitive deterioration and other geriatric syndromes. The indiscriminate use of appetite stimulants, high-calorie nutritional supplements, benzodiazepines, and antimicrobials to treat bacteriuria without specific symptoms of urinary tract infections should be avoided as much as possible[40].

The WHO supports member states in strengthening and promoting mental health in the elderly population; it also advocates for integrating effective strategies into policies and plans. The World Health Assembly adopted the Global Strategy and Action Plan on Aging and Health in 2016[41], the objectives of which include the following[42]: Commitment to action on healthy aging in every country; Developing age-friendly environments; Aligning health systems to the needs of older populations; Developing sustainable and equitable systems for providing long-term care (home, communities, institutions); and Improving measurement, monitoring, and research on healthy aging.

In May 2017, the World Health Assembly endorsed the Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025[44]. This plan provides a comprehensive blueprint for action, including increasing the awareness of dementia and reducing the risk for dementia. Apart from this, the WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) package consists of interventions for the prevention and management of priority conditions such as depression, psychosis, suicide, and substance use disorders in nonspecialized health settings, including those for older people[45]. Under universal health coverage, the WHO also recommends protecting the elderly population from financial risks, designing age-friendly benefit packages, and extending social insurance schemes for older people[46], which is another way to promote mental health in older people.

This article provides an overview regarding the available resources in mental health in order to promote the mental health of the elderly population, which can be utilized in the community by generating awareness. However, we did not discuss the availability, needs, and gaps of various resources, such as housing facilities, social safety, support, financial security, etc. Articles were sourced from the PubMed and WHO websites.

With the rapidly shifting aging demographic and changing family dynamics, the elderly population forms a sector of the population that needs specific focus. The sound mental health of elderly individuals is a cornerstone in ensuring quality and dignity of life. Thus, it is crucial to understand the sociocultural and economic factors that contribute to their mental well-being. MHP plays a vital role in establishing healthy practices, which in the long run sensitize and protect the elderly population against the deterioration of overall functionality. Elderly individuals located in the WHO SEARO region share remarkably similar sociocultural profiles. The research available in this area provides actionable data and clear pathways of MHP to improve the existing conditions for the elderly populations in these countries. There is a need to identify at-risk behavior and the existing gaps for providing care to elderly individuals. At present, we need to address these issues and challenges to maintain societal equilibrium and correct the future boom we expect in regard to the population of older adults.

We wish to thank the editorial board for inviting the submission of this article to the World Journal of Psychiatry and for giving us such an opportunity. We also wish to thank our institution and Professor Shally Awasthi, faculty in-charge, research cell, for motivating us to work on the topic and our colleague, Dr Radheshyam Gangwar, associate professor, Geriatric ICU KGMU, for supporting us in accomplishing the task on time.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Health care sciences and services

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu X S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JL

| 1. | WHO. World report on Ageing and health. 2015.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | WHO. Ageing and health. 2021.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | WHO. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. 1986.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | WHO. Promoting mental health: Concepts, emerging evidence, practice: Summary report. 2004.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | WHO. Prevention and Promotion in Mental Health. 2002.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Delle Fave A, Bassi M, Boccaletti ES, Roncaglione C, Bernardelli G, Mari D. Promoting Well-Being in Old Age: The Psychological Benefits of Two Training Programs of Adapted Physical Activity. Front Psychol. 2018;9:828. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | WHO. Decade of healthy ageing: baseline report. 2020.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | WHO. Clinical Consortium on Healthy Ageing 2019. 2020.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | UNDP. Sustainable Development Goals. 2019.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | WHO. Regional Office for South-East Asia. 2013.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Heok KE. Elderly people with mental illness in South-East Asia: rethinking a model of care. Int Psychiatry. 2010;7:34-36. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Shankardass MK. Policy initiatives on population ageing in select Asian countries and their relevance to the Indian context. Population Ageing in India 155. Cambridge University Press. . 2014. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. National Policy on Older Persons. Government of India. . [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | de Mendonça Lima CA, Ivbijaro G. Mental health and wellbeing of older people: opportunities and challenges. Ment Health Fam Med. 2013;10:125-127. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. |

Girdhar R, Sethi S, Vaid RP, et al Geriatric mental health problems and services in India: A burning issue.

|

| 16. | Tiwari SC, Tripathi RK, Kumar A, Kar AM, Singh R, Kohli VK, Agarwal GG. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among urban elderlies: Lucknow elderly study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2014;56:154-160. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tiwari SC, Srivastava G, Tripathi RK, Pandey NM, Agarwal GG, Pandey S, Tiwari S. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity amongst the community dwelling rural older adults in northern India. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:504-514. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Tiwari SC, Pandey NM. Status and requirements of geriatric mental health services in India: an evidence-based commentary. Indian journal of psychiatry. 2012;54:8-14. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Prince M, Livingston G, Katona C. Mental health care for the elderly in low-income countries: a health systems approach. World psychiatry. 2007;6:5-13. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Grover S, Avasthi A, Sahoo S, Lakdawata B, Dan A, Nebhinani N, Dutt A, Tiwan SC, Gania AM, Subramanyam AA, Kedare J, Suthar N. Relationship of loneliness and social connectedness with depression in elderly: A multicentric study under the aegis of Indian Association for Geriatric Mental Health. Journal of Geriatric Mental Health. 2018;5: 99. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Levkoff SE, MacArthur IW, Bucknall J. Elderly mental health in the developing world. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:983-1003. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | WHO. Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice: a report of the World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in collaboration with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation and the University of Melbourne. 2005.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Kumar S, Preetha G. Health promotion: an effective tool for global health. Indian J Community Med. 2012;37:5-12. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 123] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Fillit HM, Butler RN, O'Connell AW, Albert MS, Birren JE, Cotman CW, Greenough WT, Gold PE, Kramer AF, Kuller LH, Perls TT, Sahagan BG, Tully T. Achieving and maintaining cognitive vitality with aging. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:681-696. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 181] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mrazek P, Haggerty R. Reducing risks of mental disorder: frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington: National Academy Press. 1994;. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | WHO. Regional Office for South-East Asia. Integrated care for older people: a manual for primary care physicians (trainee's handbook). 2020.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | WHO. Mental Health ATLAS [Internet]. 2017.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Asia WHORO for S-E. 2019 Health SDG profile: India. 2019.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Asia WHORO for S-E. 2019 Health SDG profile: Bangladesh. 2019.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Asia WHORO for S-E. 2019 Health SDG profile: Bhutan. 2019.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Asia WHORO for S-E. 2019 Health SDG profile: Indonesia. 2019.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Asia WHORO for S-E. 2019 Health SDG Profile: Democratic People's Republic of Korea. 2019.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Asia WHORO for S-E. 2019 Health SDG profile: Maldives. 2019.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Asia WHORO for S-E. 2019 Health SDG profile: Myanmar. 2019.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Asia WHORO for S-E. 2019 Health SDG profile: Nepal. 2019.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Asia WHORO for S-E. 2019 Health SDG profile: Sri Lanka. 2019.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | Asia WHORO for S-E. 2019 Health SDG profile: Thailand. 2019.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Health SDG profile. Timor-Leste [Internet]. 2019.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Desai NG, Tiwari SC, Nambi S, Shah B, Singh RA, Kumar D, Trivedi JK, Palaniappan V, Tripathi A, Pali C, Pal N, Maurya A, Mathew M. Urban mental health services in India: how complete or incomplete? Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:195-212. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 40. | WHO. Integrated care for older people: a manual for primary care physicians (trainee's handbook). Regional Office for South-East Asia. 2020.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. | Rudnicka E, Napierała P, Podfigurna A, Męczekalski B, Smolarczyk R, Grymowicz M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas. 2020;139:6-11. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 335] [Article Influence: 83.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | WHO. The Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health 2016–2020: towards a world in which everyone can live a long and healthy life. 2016.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | Bishwajit G, O'Leary DP, Ghosh S, Yaya S, Shangfeng T, Feng Z. Physical inactivity and self-reported depression among middle- and older-aged population in South Asia: World health survey. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:100. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | WHO. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia, 2017–2025. Geneva: WHO. 2017. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | WHO. Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP). 2016.. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 46. | WHO. The world health report: health systems financing: the path to universal coverage: executive summary. 2010. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 209] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |