Published online Mar 19, 2021. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v11.i3.63

Peer-review started: December 20, 2020

First decision: January 7, 2021

Revised: January 14, 2021

Accepted: February 26, 2021

Article in press: February 26, 2021

Published online: March 19, 2021

Public stigma and self-stigma impact negatively on the lives of people with mental health issues. Many people in society stereotype and discriminate against people with mental ill-health, and often this negative process of marginalisation is internalised by people with lived experiences. Thus, this negative internalisation leads to the development of self-stigma. In this article, I reflect on my own experiences of shame and self-stigma as a person with mental ill-health socially bullied by peers from my community and social groups. I present a personal narrative of both public and self-stigmatisation which I hope will enable me to exorcise memories of internalised stigma, which are encountered as my demons of lived experience. Using reflexivity, a process used widely in health and social care fields, I consider how social bullying shattered my fragile confidence, self-esteem, and self-efficacy in the early days of my recovery; the impact of associative stigma on family members is also explored. Following this, the potential to empower people who experience shame and stigma is explored alongside effective anti-stigma processes which challenge discrimination. I connect the concept of recovery with the notion of empowerment, both of which emphasise the importance of agency and self-efficacy for people with mental ill-health. Finally, I consider how the concepts of empowerment and recovery can challenge both the public stigma held by peers in the community and the self-stigma of those with lived experiences.

Core Tip: The article explores the experiences of stigma and discrimination experienced by a person with lived experience of mental ill-health. It explores how both public stigma and self-stigma can shatter fragile confidence and impact negatively on both self-efficacy and self-esteem. Connections with the importance of empowerment and recovery in mental health are considered, and how they can overcome the sense of shame and self-pity experienced by people with mental ill-health who encounter social bullying by peers in their community.

- Citation: Fox JR. Exorcising memories of internalised stigma: The demons of lived experience. World J Psychiatr 2021; 11(3): 63-72

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v11/i3/63.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v11.i3.63

Stigma is at the centre of the experiences that many service users encounter when in contact with their peers and with the communities they belong to[1-3]. The word stigma originates from ancient Greek and means ‘a mark of shame or discredit’[4]; this defines the exclusion and marginalisation that many people with mental ill-health experience. Two elements to stigma have been defined: Public stigma and internalised stigma[1]. Public stigma involves the construction of stereotypes about excluded groups. This process leads to prejudice which is translated into active discrimination and marginalisation against this population[1]. Self-stigma[1,5] involves the internalisation and acceptance of negative beliefs about mental illness. These elements interact[5] because people who live with conditions such as schizophrenia may also endorse stereotypes about themselves, leading to “self-discriminating behavior” such as self-imposed isolation derived from the stereotype held by others about their “risky and dangerous” behaviours. Self-stigma reduces individuals’ self-efficacy and self-esteem[1,5]; moreover, internalized stigma can disrupt mental health treatment-seeking intentions and behaviours and can lead to delayed help-seeking[6]. Stigmatisation processes can also affect family members of people diagnosed with mental ill-health.

This article will explore my lived experiences of stigma as a person with a diagnosis of mental-ill health and reflect on the response by peer groups to my condition. It asks questions about the nature of both public and internalised stigma[1,5] and investigates the lack of understanding of mental health symptoms. I explore the processes that can challenge both public and internalised stigma and suggest how anti-stigma campaigns can confront discrimination. I finally propose how acts of empowerment and the concept of recovery can both challenge stigma and promote greater understanding of mental ill-health.

I am both a social work academic and service user expert with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Both these identities are central to the construction of this article as I reflect and analyse my experiences about the nature of stigma. At the centre of social work is the process of reflection and reflexivity, a method used to enable professionals to understand and make sense of their experiences[7]. Reflexivity enables a person to explore his/her experiences and interpret them to gain greater understanding of the context to the situation around him/her[7]. A useful method that enables reflexivity is a process that explores the art of writing and reflection in investigating practice[8]. This approach connects the narratives of lived experiences told through personal reflections to the context of practice[8], exploring the links between local encounters and the wider circumstances. I thus relate my lived experiences of stigma and illuminate their significance for understanding the wider environment through a process of reflection. This method has been used in health, social care, and education and can facilitate an investigation of the significance of personal reflection in the setting of professional practice[8].

This is for me a frightening and revealing reflection. It focuses on my sense of shame and stigma as a person with mental ill-health. It is hard to write as this process reveals details of experiences I have not spoken of before or allowed to bubble to the surface. These are accounts which I have hidden deep and buried in forgotten memories. They are embarrassing and shameful-and best forgotten. But at times they can’t be forgotten and come to the surface.

At the time of the experiences described in this reflection, I was very paranoid and found it difficult to manage my mental health symptoms. I heard conversations and thought that people were talking about me. I translated the words I heard into what I wanted to hear – words that had been unsaid. These are my demons of lived experience through the shame and embarrassment I encounter as I remember them.

I experienced a mental health crisis involving extreme paranoia and psychosis at the age of 18-years-old. This happened at university in the North of England in the early 1990s. At the time I was studying at university far away from home. I had no personal experience of mental ill-health and had no inkling or understanding of its manifestation. At that time, I believed that mental illness happened to “mad” people, and was not something I would experience; moreover none of my peers or tutors recognised the signs of a pending mental health crisis until the illness was quite advanced.

My parents came to visit me at my university; this visit coincided with my first episode of mental health crisis. My mother stayed in the university as my mental health was deteriorating. I eventually had an appointment to see a psychiatrist and was admitted voluntarily for a short hospital stay and prescribed medication. On leaving hospital, I continued to take medication and returned to university. I continued to experience paranoia and low levels of psychosis and was eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia two years later. I continued my university studies, with great difficulty, and finally graduated. I was awarded a lower degree classification than previously predicted; however, completion of my university degree was a real achievement.

However, alongside this success at completing my degree, I also experienced many episodes that caused (and still cause) me shame and embarrassment. I remember back to experiences of when I was unwell, and I cringe. After leaving university I returned home to live with my parents. I was very lonely and isolated and craved a relationship with somebody who would like me for who I was, support me and take care of me. I was naïve, dependent, and overweight, because of the increased appetite associated with taking the prescribed anti-psychotic medication. I had little self-confidence and felt a sense of shame at who I was. I so much wanted to be valued.

There are so many memories that cause shame and embarrassment. I remember. I really liked somebody. This person was in a social club which I joined at the age of 23-years-old. The social group was a small group of 10 people for those aged 20-30-years-old (It wasn’t a mental health peer group, but a social group in the community). There were some people who became my friends in the group; they were kind and thoughtful, but some who were unkind and found a mental health issue to be amusing. The group members all had more “success” than me. I was still living at home, undertaking additional study, and trying to forge a life for myself. But I was still dependent on my parents, and I lacked self-worth. This person who I liked didn’t like me. I couldn’t accept it and I believed that he liked me.

I listened like a snake to the conversations of other people. I listened to their conversations for evidence that he liked me. I heard things the people didn’t say, and when I would go over their words, I would hear the words that he liked me. Words that hadn’t been said, but I remembered as being said. Few people without lived experience of mental ill-health, can understand how paranoid beliefs may be perceived as a true representation of the world; my peers couldn’t understand that I believed these thoughts to be true. At times people in this group teased me because I was a sad and very lonely person. They would say that he liked me, but he didn’t; some people teased me because I couldn’t seem to accept the obvious. During this period, I was like a ship, lost at sea, hurtling from one wave to another. I always ask the question: Did those people treat me unkindly and without compassion, or did they just not understand? As I remember I cringe with embarrassment and shame. Was it my fault? I had a mental health illness. They didn’t understand the impact on me.

To my lasting shame and stigma, I had a pattern of such behaviour. I would latch onto somebody and believe he liked me. I was lonely and isolated and so wished for somebody to care for me. Previously to this experience, I kept such thoughts silent and did not share them, but this situation was different as I truly believed he liked me. I was a persistent re-offender! My behaviour wasn’t obvious, and I didn’t harass him, I was a bit of a “silly nuisance”! He didn’t understand my pain and embarrassment, I don’t think he noticed me, only I experienced the shame.

This internalised failure is linked to the messages I reinforced to myself when I wasn’t well. You can’t do that. You aren’t good enough to do that. You are no good. These are the demons of internalised stigma that say you can’t achieve; that you are no good. This is a narrative of pain. I was bullied, undermined, and shamed as they laughed at me. Did they know the impact on me?

I managed the day-to-day stigma by convincing myself that I was of no value and self-reinforced the stigma others felt towards me; this meant my confidence plummeted. This was a negative coping mechanism which was effective because it dulled all hope and optimism; I couldn’t be hurt anymore and couldn’t fall any further because I had failed utterly.

What saved me from being this sad and lonely person? Eventually by engaging with learning, study, and being supported by mentors throughout my social work career, I began to achieve and to succeed. I studied for a Master of Arts degree in Social Work, then a PhD. Work for me was at the centre of my recovery journey and enabled me to fight the stigma; it led to a passion to change public stigma for those experiencing mental distress. Finding a wonderful and considerate and understanding man who became my husband was at the centre of my recovery. I am not now the person who was that person at that point in time described in my reflection. I cringe at my loneliness, my embarrassment, my shame, and my isolation. Was it my fault or was it part of my recovery journey?

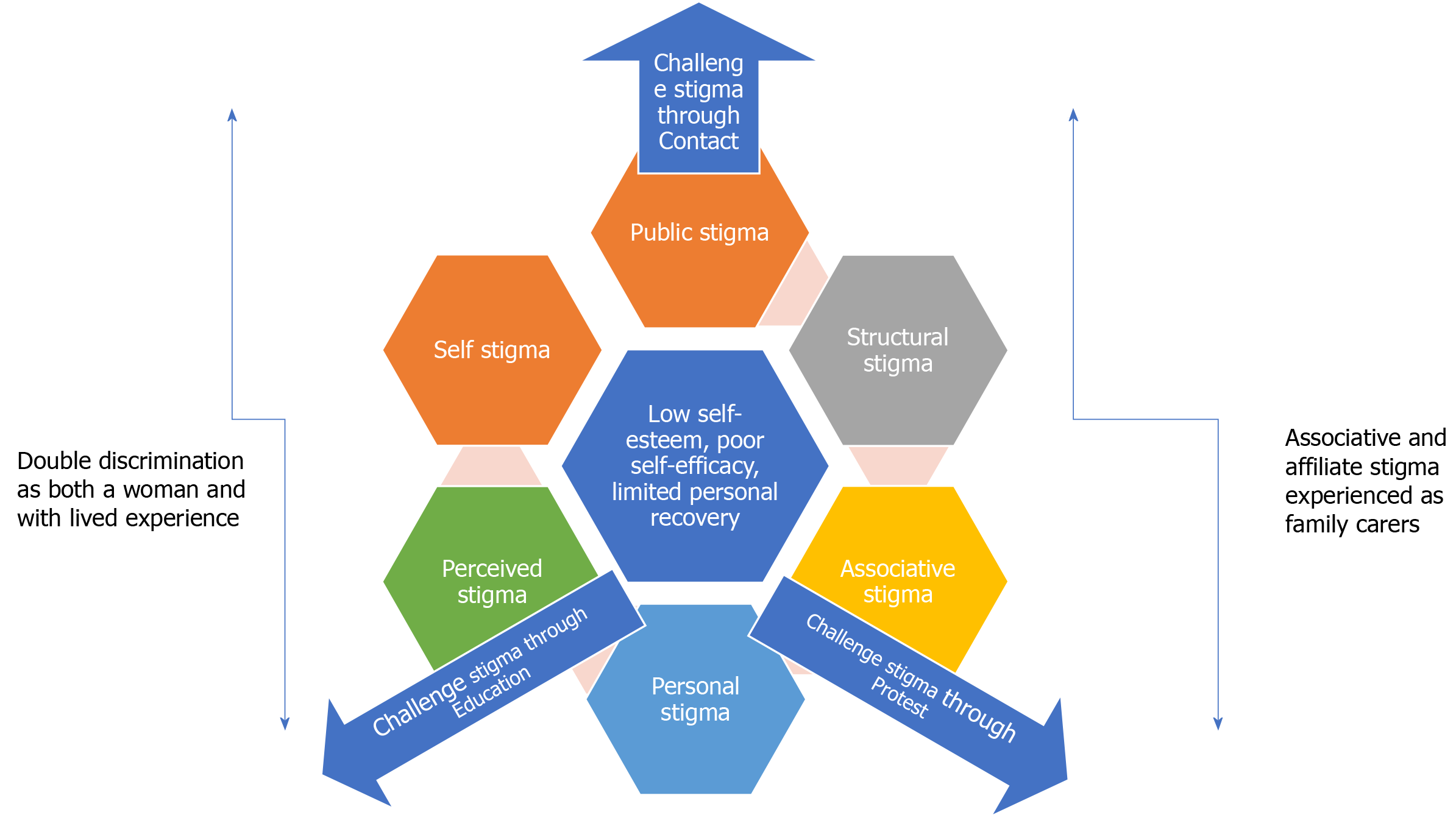

In the following section I discuss my reflection and contextualise the experiences in the wider literature which seeks to explore the impact of mental health stigma in society. It is important to illuminate how stereotypes and prejudice impact on people with lived experience, and lead to their sense of shame and exclusion from society. Figure 1 highlights different types of stigma encountered in my life which resulted in my low self-esteem, poor self-efficacy and which limited my recovery. It provides a framework to explore discussion in this article. The elements of stigma represented in Figure 1 include: Public stigma, structural stigma, associative stigma, personal stigma, perceived stigma, and self-stigma. Alongside the cycle of stigma, my own experiences of double discrimination as both a woman and a person with lived experience of mental ill-health are depicted; these underpin the experiences of social bullying. Whilst parallel to these feelings, but outside of my direct encounters, the associative and affiliate stigma experienced by my family are identified. Finally factors that help to challenge stigma in society, such as protest, education, and contact push out against the cycle of stigma to counteract discrimination and marginalisation. These factors, captured in Figure 1, are elucidated in the article discussion.

The social identity of a person with mental ill-health is often negatively construed because the individual does not conform to social expectations of working and living independently[9]; this thus leads to them being stigmatised and devalued and experiencing public stigma. Furthermore, as people absorb this negatively constructed social identity, this then leads to forms of internalised stigma, or self-stigma, in the individual because of negative attitudes aimed at them.

The stigma encountered by people with mental health issues has been widely explored in research[1,2,5]; perhaps the most well-known forms of stigma are public and self-stigma[1]. However, stigma exists in many forms across cultures[2]: Within the individual (self-stigma), interpersonally (personal stigma), in the shared beliefs of a social group (public stigma), and in the policies and practices that structure society (structural stigma). Figure 1 shows the elements of stigma which constrained my recovery, first exemplified in structural stigma derived from public stigma.

Structural stigma is an important concept to highlight as it expresses how stigma can exist throughout a culture and become endemic in a system[9]. From my narrative, it seems clear that my peers believed that it was acceptable for them to tease me because I was a person with mental ill-health to be pitied and undermined. The acceptance of structural stigma[9] allowed them to bully me because I was a person who was devalued and of no worth.

Furthermore, three different reactions[10] by the community to people with mental health issues have been identified. Firstly, authoritarianism is the belief that people with mental health issues are not able to take care of themselves and need other people to take control and direct their lives. Secondly, there is a response to people with mental ill-health that is based on fear and exclusion. This reaction is founded on the belief that people with mental health problems are dangerous and should be isolated from their communities. The final reaction generated in response to people with mental ill-health is benevolence. This response is based on the belief that people with mental health issues are innocent and naïve and not able to make decisions for themselves, resulting in paternalistic help being offered. Such a reaction from peers in their community is often compounded with feelings of annoyance and anger towards people with mental health issues.

Thus, in my experiences I was a person to be excluded and isolated; my peers also felt a benevolent response towards me. I was treated with paternalism as they directed annoyance and anger towards me. I was to be pitied but simultaneously an object unable to manage her own emotions, unable to live independently, of potential risk because I failed to respond in “normal” and socially acceptable ways to my peer group. The process of structural stigma led to a sense of low self-esteem and poor self-efficacy, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Furthermore, six further forms of public stigma have been highlighted[11]; however only three are mentioned here which I particularly relate to in the context of this article. I thought I was unable to fulfil social positions (exclusionary sentiments); I believed my mental health treatment had negative effects on my social status; (treatment carryover concerns) and I believed my family experienced negative consequences from my mental health status (disclosure spillover).

Associative and courtesy stigma[11,12] were encountered by my family members This type of stigma is a process in which a person is stigmatized by virtue of his/her association with another stigmatized individual. Additionally affiliate stigma occurs when care-givers’ psychological responses to caring are impacted by the public stigma that prevails in society and they internalise self-stigma[13]. My parents supported me to the best of their ability, but they didn’t always understand the shame and stigma that I experienced. My family felt personally impacted by the negativity of my diagnosis; and were unable to talk to their peers in their community, encountering affiliate stigma[13]. As shown in Figure 1, their experiences were encountered in parallel to my exclusion but were different to and outside of the stigma I suffered as a person with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. They sought support from peer and mutual aid support groups at moments in their caring journey. However, I felt uncomfortable with them attending such groups because I believed they talked solely about my mental ill-health in these environments. I didn’t recognise or acknowledge that they had their own needs as care-givers. However, eventually, the fears I expressed prevented them from accessing any forms of support. My parents were therefore further isolated through the feelings of self-stigma; and, thus, stigma limited the recovery of both me and my social network.

These elements suggest that underpinning public stigma[1] are elements of fear[14], a desire to keep a social distance[10], a devaluing of the role of people with mental health issues[9]; fears that association with someone with a mental health issue can cause feelings of exclusion[10] or “courtesy stigma” and associative stigma[11,12]. These elements connect to the process of self-stigma in both myself and my parents[1,11] associated with internalising the notions of social exclusion and the inability to manage an independent life[14]. These elements of exclusion led to the belief that I was deserving of pity, that I was shameful and thus deserving of stigma.

The issue of perceived stigma may also be in play in this context[15,16]. Perceived stigma concerns how a person with mental ill-health anticipates a negative reaction from others about their diagnosis; it is particularly relevant to those people who want to be open about their diagnosis[15]. Moreover, this interacts with a sense of self-stigma as indicated in Figure 1. I anticipate a negative reaction from some people in my social circles and thus choose not to disclose my diagnosis. For example, I have not shared my diagnosis with some close family members from a fear about how they might react-I perceive that the diagnosis of schizophrenia is often linked to notions of dangerousness and anticipate a negative response. However, although I choose not to reveal my diagnosis in many social settings, I often divulge these experiences in many academic circles[17]. I have a passion to use my expertise-by-experience to change mental health services for the better and yet feel a need to protect myself from people who don’t understand mental ill-health. This decision about when to reveal my diagnosis leads to an anomaly of when I choose to disclose my status and when I choose not to[17].

Returning to my experiences of exclusion, women with mental health conditions[18] often experience social devaluation through a double disadvantage based on the intersection of being both a woman and a person with a mental health condition. Such discrimination was reflected in the historical devaluing of women through the early diagnosis of hysteria, labelled as a mental health condition linked to women’s health and reproductive cycles[18]. Women with mental illness, who have experienced trauma, highlighted more difficulties with low self-esteem and the stigma connected to lived experiences than women who have not experienced trauma[18]. The trauma and social bullying that I received ripped out my sense of self-esteem and self-efficacy, limiting my recovery and leaving me a pitiable and empty shell. This process of stigma is depicted in Figure 1, whilst the double discrimination of being a woman and having lived experience of mental ill-health is illustrated as existing alongside these feelings.

Furthermore, the connection between perceived stigma and experiences of victimisation for people with mental health needs has been considered in other studies[19]. Perceived stigma and victimization are significantly associated, and the stigma attached to mental illness[19], from being perceived as being dangerous, violent, or undesirable, is a statistically significant predictor of victimization experiences. However, there is little understanding of the experiences of those with mental health issues; particularly as women with mental ill-health often experience an intersection of stigma and victimisation by their peer and friendship groups[18,19], as I describe above.

More widely, the cultural heritage of people with mental ill-health can impact negatively on their experiences of acceptance in their peer and friendship groups[10,20]. Public from Eastern countries ascribed more moral attributions to people with mental illness than from Western cultures[10], thus increasing the potential to discriminate. Moreover, people from Western countries endorsed higher stigma (prejudice and discriminatory potential) and made more moral attributions when the target was a minority (as compared with majority) group member. Furthermore, concern for loss of face in Eastern cultures is part of the process preventing individuals from seeking help from mental health providers to prevent shaming one’s family[20], because mental health conditions are highly stigmatized in Chinese communities. In the United Kingdom, there has been an ongoing national anti-stigma campaign, Time to change, which has sought to challenge stigmatisation and discrimination against people who experience mental ill-health[21]; it has achieved some limited success.

This section has underlined the stigma and discrimination experienced by people with mental ill-health, highlighting the potential of victimisation to this group, and particularly to women who experience double discrimination. Figure 1 captures how I have experienced different types of stigma which have limited and bounded my potential recovery journey, and that of my family. Subsequently, an acknowledgement of the importance of cultural heritage in this context has also been considered. In the next section the paper considers how society can challenge the stigma and marginalisation of those who experience mental ill-health.

People with mental ill health may sometimes challenge this sense of self-stigma through reactions of “righteous anger”[1] about the negative social identity ascribed to them by their community. Moreover, a sense of righteous indignation, particularly associated with collective activism and group identity, can challenge both individual and group prejudice. For example, the experiences of 800 gay and bi-sexual men were explored[22] and a sense of belonging and group activism was positively associated with improved self-esteem; indeed, extrapolating to mental health there may be “high feelings of self-esteem” from “experiencing group identity”[1]. Despite this process of empowerment, individuals who are stigmatised can resist this label by claiming their own exceptionalism to the stereotypes, thus challenging stigma as an individual[2].

A process of empowerment can help people to gain a sense of control in their lives and can foster independence and agency[5], challenging the stigma they may experience that results in dependency and low self-efficacy. Indeed, “empowerment is the flip side of stigma, involving power, control, activism, righteous indignation, and optimism”[5]. The importance of empowerment in tackling self-stigma is reinforced in the context of promoting control over treatment choices and the direction of one’s life[23]. Empowering people in these choices can increase a sense of autonomy and agency, thus resulting in a positive effect on self-stigma.

Empowerment cannot happen without change in individuals and the systems around them. From their standpoint as art therapists[24], the issues of stigma and shame met by people with mental health issues were surveyed in one study. This study noted how people with mental ill-health are often devalued in society and their role is seen as inconsequential. Such ideas in the field of mental health are related to the context of learning disability, where the importance of social role valorisation is explored, a concept[25] developed to understand the need to empower people with learning difficulties and enable them to be respected and valued in their social role.

In the discussion above, it was identified that stigma against people with mental health needs derives from having a negatively construed social identity. The field of learning disabilities research offers a lot to learn in supporting the promotion of people with mental health issues as full and respected citizens with a valued social role. This leads to the question of how can society combat both public and self-stigma?

Three strategies to help overcome mental health stigma are explored in the literature[10]: Protest, education, and contact. Firstly, protest is the process of challenging people’s negative beliefs through direct action. Secondly, education involves the provision of brief courses or facts to counteract prejudice. Finally, contact consists of directly promoting one-on-one contact between people with lived experience of mental ill-health and the public. Contact is found to be the most effective way of challenging stigma and changing attitudes. Moreover, “face-to-face contact with the person, and not a story mediated by videotape, had the greatest effect” at challenging stigma[21]. The role of each of these factors in challenging stigma is illustrated in Figure 1, as they push out of the cycle of stigma that I depict as representing my experiences.

Anti-stigma campaigns need to balance wide and broad approaches that seek to challenge discrimination in a large population of people with more local campaigns which focus on challenging the opinions of small groups[26]. This finding is reinforced by another study[27] which suggests that such strategies could be developed to also reduce self-stigma in people experiencing mental health issues. However, little is known about what elements of contact are effective in challenging stigma[10]; for example, is it equal status or promoting understanding about experiences of mental ill-health that makes contact-based strategies effective? It is essential to answer this to understand how to effectively tackle discrimination and marginalisation of people with mental ill-health.

Encouraging people with mental health needs to disclose their mental health condition may help to reduce stigmatization as individuals take control of information about their health condition and can become empowered[5]. However, on one hand, disclosing psychiatric status can have negative implications because it can cause discrimination and prejudice, on the other, people who disclose often report lower levels of self-stigma, a greater sense of personal empowerment, higher self-esteem, and enhanced quality of life[5]. Despite this, the value of disclosing a diagnosis such as schizophrenia is questioned because of the high stigma associated with this condition[28].

It appears that the process of “contact” to reduce stigma needs to be carefully managed. There needs to be further research about what elements of contact effectively challenge stigma[10] and how people with a mental health condition can be appropriately supported through the process of disclosure[28]. Empowerment is key to challenging self-stigma and enabling the person to challenge both self-stigma and public stigma. Moreover, difference and disdain are key measures of stigma; a recent study explored how to manage these issues in the context of mental health[29]. They investigated how difference results in people with mental illness being alienated and othered making a separation of “us” from “them”. Consequently, this sense of difference leads to disdain because people with mental illness are devalued and disrespected. The study concludes that anti-stigma efforts may best be focused on tackling elements of disdain, rather than difference, because disdain seems to be the main driver of self-stigma[29]. This focus on empowerment can be achieved by promoting messages such as: “I may be different, but I am not a person of lesser value.”

Moreover, in the United Kingdom, the anti-stigma campaign, Time to change[21] has achieved some success in challenging stigma through publishing the personal narratives and stories of those who have lived experience of mental distress; this reflects the acceptance by service users that they may be potentially “different” from other people in society and may have different stories to tell, but that they are not of lesser value. Maybe other people without lived experience of mental distress come to acknowledge their own differences and idiosyncrasies as art of the process of learning about differences?

Such processes of empowerment build on the seminal work in the field of learning disability theory of social role valorisation[25] that highlights the importance of having a respected and valued role in society. Furthermore, empowerment, enhancing service user control, and self-management of a mental health condition are at the centre of the recovery approach[30] an aspirational practice in mental health that emphasises the importance of people with mental ill-health leading a good life despite the limitations of their illness[31]. Indeed, recovery is, in itself, an “effective message” to combat stigma because it reinforces that “mental illness does not keep a person from achieving a full range of positive outcomes”[30]. This process of empowerment through promoting recovery may be a key factor in challenging both the public stigma and self-stigma of people who have mental ill-health because recovery emphasises the importance of achievement, respect and value for this group[31].

As my reflection shows, occupying a valued social role and beginning to follow my dreams enabled me to begin to reconstruct my brittle self-esteem and self-efficacy. Little by little, building on confidence and true friendship, I was enabled to take on a responsible role as an academic and increase my capacity to perform[32,33]. Recovery was at the centre of my empowerment and led me to a place of increased confidence and self-esteem[32,33] where I was able to combat my own sense of self-stigma and challenge the public stigma of being a person with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. This place led me to exorcise the demons of lived experience. Thus, drawing on the research presented in this article, it is suggested that increased contact between people with lived experiences, and their peers in the community, based on respect and value[10,28], and the representation of stories of recovery[32,33], may be at the centre of promoting the social value of people with mental ill-health.

Thanks to Linda Homan for reading and reviewing my article.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Social Work England, No. SW47539.

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chakrabarti S, Kishor M S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin Psychol Sci Prac. 2002;9:35-53. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Corrigan P, Watson A, Bar L. The self-stigma of mental illness: implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2006;25:875-884. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 674] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 687] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dobransky KM. Reassessing mental illness stigma in mental health care: Competing stigmas and risk containment. Soc Sci Med. 2020;249:112861. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Marriam Webster Dictionary. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stigma accessed 07.12.20. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Corrigan PW, Rao D. On the self-stigma of mental illness: stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57:464-469. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 450] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 424] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hughes C, Fujita K, Krendl AC. Psychological distance reduces the effect of internalized stigma on mental health treatment decisions. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2020;50:489-498. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fook J. Social Work: A Critical Approach to Practice. London and New York: Sage, 2016. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Winter R, Buck A, Sobiechowkska P. Professional experience and the investigative imagination. The ART of reflective writing. London and New York: Routledge, 1999. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Overton SL, Medina SL. The stigma of mental illness. J Couns Dev. 2008;86:143 -151. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 117] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Couture SM, Penn DL. Interpersonal contact and the stigma of mental illness: A review of the literature. J Ment Health. 2003;12:291-305. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 213] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Catthoor K, Schrijvers D, Hutsebaut J, Feenstra D, Persoons P, De Hert M, Peuskens J, Sabbe B. Associative stigma in family members of psychotic patients in Flanders: An exploratory study. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5:118-125. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Judgeo N, Moalusi KP. My secret: the social meaning of HIV/AIDS stigma. SAHARA J. 2014;11:76-83. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shi Y, Shao Y, Li H, Wang S, Ying J, Zhang M, Li Y, Xing Z, Sun J. Correlates of affiliate stigma among family caregivers of people with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2019;26:49-61. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Krendl AC, Pescosolido BA. Countries and cultural differences in the stigma of mental illness: The East–West divide. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2020;51:149-167. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zieger A, Mungee A, Schomerus G, Ta TM, Dettling M, Angermeyer MC, Hahn E. Perceived stigma of mental illness: A comparison between two metropolitan cities in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58:432-437. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Carta MG, Schomerus G. Changes in the perception of mental illness stigma in Germany over the last two decades. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29:390-395. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fox J, Gasper R. The choice to disclose (or not) mental ill-health in UK Higher Education Institutions: a duoethnography by two female academics. J Organisational Ethnography. 2020;9:295-309. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Frieh EC. Stigma, trauma and sexuality: the experiences of women hospitalised with serious mental illness. Sociol Health Illn. 2020;42:526-543. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Harris MN, Baumann ML, Teasdale B, Link BG. Estimating the Relationship Between Perceived Stigma and Victimization of People With Mental Illness. J Interpers Violence. 2020: 886260520926326. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chen S, Mak WWS, Lam BCP. Is it cultural context or cultural value? Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2020;11:1022-1031. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | We're a campaign to change the way people think and act about mental health problems. In: Time to change (cited February 23, 2021). Available from: https://www.time-to-change.org.uk/. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Frable DES, Wortman C, Joseph J. Predicting self-esteem, well-being, and distress in a cohort of gay men: The importance of cultural stigma, personal visibility, community networks, and positive identity. J Pers. 1997;65:599-624. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 82] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Corrigan PW, Kerr A, Knudsen L. The stigma of mental illness: Explanatory models and methods for change. App Prevent Psychol. 2005;11:179-190. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 131] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Carr S, Ashby E. Stigma and shame in mental illness: avoiding collusion in art therapy. Int J Art Therapy. 2020;25:1-4. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wolfensberger W, Nirje B, Olshansky S, Perske R, Roos P. The principle of normalization in human services. In: Social Work. Toronto: National Institute on Mental Retardation, 1972. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rüsch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:963-973. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 835] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 728] [Article Influence: 60.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Li XH, Zhang TM, Yau YY, Wang YZ, Wong YI, Yang L, Tian XL, Chan CL, Ran MS. Peer-to-peer contact, social support and self-stigma among people with severe mental illness in Hong Kong. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020: 20764020966009. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. The stigma of mental illness: effects of labelling on public attitudes towards people with mental disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108:304-309. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 291] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Shah BB, Nieweglowski K, Corrigan PW. Perceptions of difference and disdain on the self-stigma of mental illness. J Ment Health. 2020: 1-7. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Corrigan PW, Bink AB. The stigma of mental illness. Encyclopedia of mental health, 2016: 230-235. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:445-452. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1480] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1235] [Article Influence: 95.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fox J. ‘The view from inside’: Understanding service user involvement in health and Social care education. Disabil Soc. 2011;26:169-177. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Fox J. Being a service user and a social work academic: Balancing expert identities. Soc Work Edu. 2016;35:960-969. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |