INTRODUCTION

The advent of assisted reproductive technology (ART), almost a century ago, came about through the clandestine use of donated sperm[1]. The use of donated oocytes, only first described in 1983, was used to establish pregnancy in a patient with primary ovarian failure[2,3]. Today, the use of donated oocytes and embryos has increasingly become routine for in vitro fertilization (IVF) clinics accounting for almost 11% of all IVF cycles reported in the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ART/CDC registry[4]. Through the landmark efforts of the groups at Monash University and the University of California, Los Angeles, this technology has resulted in more than 50 000 births in the United States (US) alone[5,6].

The use of 3rd party reproduction, including donors and surrogates, has gained increasing acceptance among patients, and now plays a major role in treating intractable problems related to oocyte function. In 1992, oocyte donation was successfully extended to women over the age of 50, revealing that women of any age could theoretically become pregnant, though collectively creating public debate about the limits on the use of the technology and whether IVF clinics should set age limits for their patients[7]. While some of the sensationalism has subsided, today, most feel that human oocyte and embryo donation is ethically and socially acceptable[8].

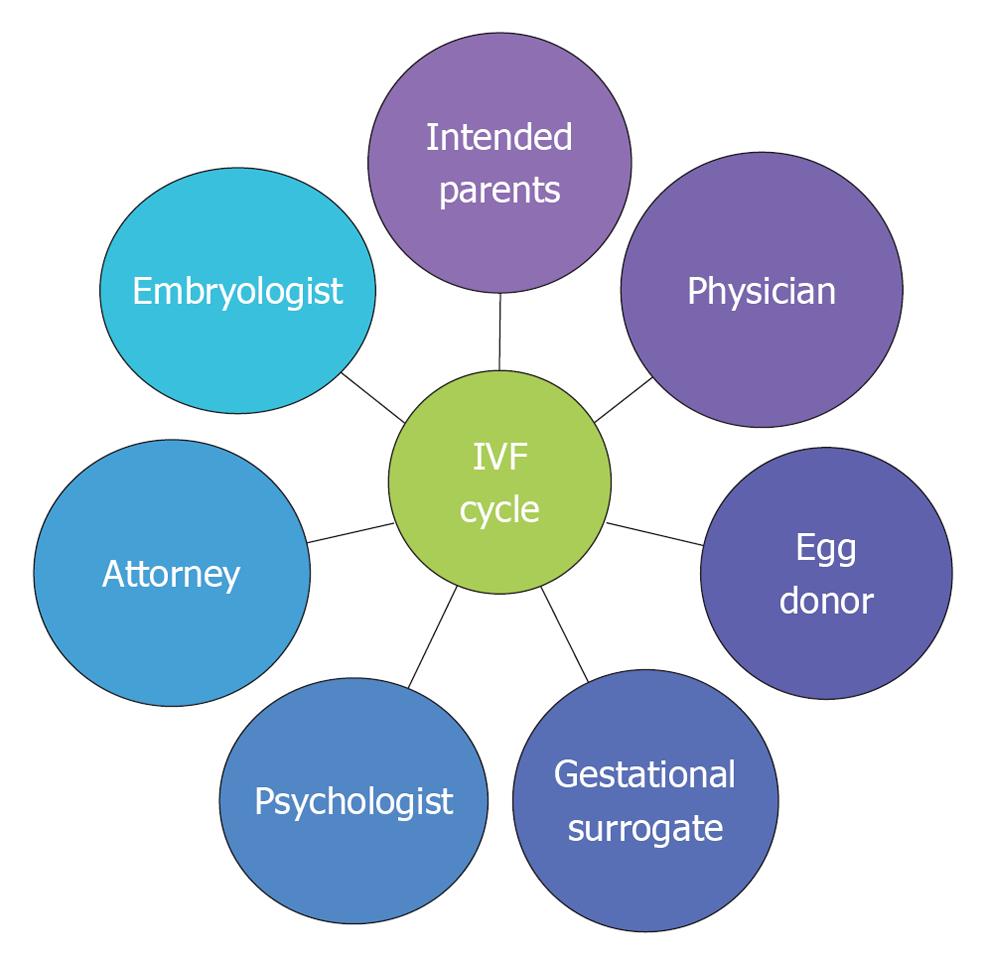

As such, the increased utilization of oocyte and embryo donation continues to present us with ethical quandaries that impact broad social and legal questions. This review focuses on some of the more recent and evolving issues that currently are and will be confronting us in the upcoming years. Given the complexity of ethical questions, finding answers to the questions may be achieved by ending the isolation of reproductive professionals and instead promoting increased and consistent communication and case consult among physicians, embryologists, therapists and attorneys (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Coordinated efforts among multiple reproductive health professionals.

REMOVING THE BARRIERS TO COMMUNICATION: CLOSING THE CIRCLE AROUND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) guidelines have established extensive recommendations for screening and testing oocyte donor candidates[9]. As part of the screening process, donors undergo medical evaluations, sexually transmitted disease and genetic screening. The donor consenting process needs to include a comprehensive discussion of medical risks and psychological issues. The psychological assessment should evaluate for evidence of coercion (financial or emotional) and is intended to ensure that the donor is made aware of all relevant aspects of medical treatments, including the ability to comply with the rigorous schedule and discomforts of injectable drugs. The ASRM also states that candidates should be informed of all aspects of potential oocyte and embryo management as well as final disposition applicable to each practice. The psychological evaluation serves to identify potential ambivalence that may be resolved prior to undergoing an oocyte donation cycle.

It has been recommended that donors and recipients have separate legal counsel, as legal agreements have increasingly become a central component of the process and are required in some states[10]. Legal agreements are used to describe and memorialize the expectations, duties and responsibilities of both the donor and recipient. A consultation informs participants of their legal rights and addresses parentage presumptions. The legal consult should include implications of options and decisions, and should be initiated early in the evaluation and screening process to ensure that the donor and the recipient’s expectations are allied. The object of involving the legal team earlier in the process is to reduce the surprises at the end once a clinic has “approved” the donor, and suddenly the parties realize that they have fundamentally different expectations regarding a major aspect of their relationship.

Agencies and ART clinics, however, are not bound by ASRM guidelines, and clinics develop their own processes as evidenced by the variation among donor-recipient experiences. Communication, disclosure, amount of information gathered and shared, written agreement requirements and degree of involvement of attorneys are highly variable among agency and clinic practices. All too often, psychological recommendations fail to include a discussion of the donor’s wishes about future use of embryos or wishes about future contact (personal experience: Lindheim SR and Jaeger AS). Many times agencies and clinics refuse to release psychological evaluations to attorneys, despite HIPAA and other documented consent allowing the release of information to them, which stonewalls the legal process and requires yet another discussion of the donor’s wishes (personal experience: Jaeger AS). This variability makes the process potentially even more overwhelming and anxiety-provoking for intended parents.

While ASRM recommends legal involvement, they do not specify when in the process this should be initiated. Practically speaking, oocyte donation cycles should only be commenced once all medical screening and testing is completed, as well as completion of consents and the legal discussion and agreements finalized. Often the legal agreement, however, is not initiated or completed until the donor is set to initiate her medications. Two clinical situations serve as a point. First, a couple who had successfully undergone an oocyte donation cycle, re-contacted the Program to donate their remaining cryopreserved embryos to the Embryo Donation Program. Upon review of their executed legal agreements, the donor had declined this option in her donor legal agreement, yet the donation was concordant with the donor’s stated desires to the medical-clinical team and her executed consent to treatment. In the second scenario, at the request of the recipient couple, the ART Program contacted the donor to change her disclosure preferences in contravention to her previously signed donor-recipient agreement to decline any future information sharing with her intended recipients. The ART program threatened to withdraw their approval of her participation if she did not agree to this change. In addition to unilaterally persuading the donor to violate the terms of the agreement, the ART Program also violated the donor’s right to counsel and disrupted the attorney-client relationship, since the attorney for the donor was not notified of the unilateral change. The clinic undermined the donor’s entire understanding of the relationship and created distrust among the parties.

A recent report suggested that more than 60% of donor-recipient legal contracts are discrepant from their consents regarding level of information sharing and oocyte and embryo directives and management[11]. This suggests that donors often reconsider several aspects of their decision to donate during the time elapsed between their consents and final legal agreements. Several possibilities for this discrepancy can be suggested. A donor may feel (1) deliberate reflection and change regarding her donation; (2) impulsiveness to speed the process where financial incentives may accentuate this feeling; (3) coercive effects from medical professionals, donor agencies, or reproductive attorneys; or (4) confusion.

There is data to suggest that oocyte donors often reconsider several aspects of their decisions during the time elapsed between initial discussions, consenting and their actual egg donation. Researchers have noted that, as donors become more knowledgeable and experienced with the donation process, they may become more comfortable and more willing to assert their opinions and their attitudes may change over time[12,13]. On the other hand, the escalation of payment suggests that money has become a dominant factor and a highly motivating interest. The “new age” donor appears less interested in the needs of the couple than her own employment by the ART program/agency. Many professionals both inside and outside the field of assisted reproduction have concerns regarding the seductive nature of financial incentives, whereby oocyte donors may be unable to adequately weigh the risks of ovarian hyperstimulation, oocyte retrieval and issues relevant to future information sharing and oocyte-embryo management and disposition. With the growing demand for oocyte donors, the pressure to complete these cycles by both recipient couples and donor agencies, who more often have donors already matched for future cycles, puts enormous pressure on programs to speed the process and fulfill the presumed needs of oocyte donors and recipient couples.

Since post-donation satisfaction is negatively correlated with pre-donation financial motivation and pre-donation ambivalence, it is essential to understand and support the impact of changes in donor preferences to further improve all parties’ satisfaction[14,15]. While ART programs have limited resources including staff and professional personnel to address these issues, today more then ever, those participating in gamete donation have an ethical obligation and a legal duty to understand, respect, and counsel all involved parties’ disclosure desires through comprehensive informed consent and counseling processes. Egg Donor programs, both in-house and agencies, should establish policies regarding disclosures and re-contact procedures.

This calls for a collaborative process among all reproductive health professionals who interface with both the intended recipients and oocyte donor. Programs should work closely and cooperatively with donor agencies and reproductive attorneys who prepare donor-recipient agreements so that contract provisions match the desires and wishes of both parties. A concerted effort to uncover and communicate such changes is essential for all professionals involved to distinguish among deliberate reflection, impulsiveness, duress, need for clarity or to reduce confusion in order to maximize third party participants’ (donors and recipients) positive experiences. Collaborative efforts that have been employed include consented release to their attorney information regarding level of future information sharing and oocyte directives and management. Inclusive flow of information and communication among reproductive health professionals supports the notion that “Closing the Circle” will help overcome obstacles and avoid potentially significant legal battles.

DILEMMAS AND OBLIGATIONS SURROUNDING DISCLOSURE OF MEDICAL OUTCOMES

ASRM has published guidelines which state all prospective donors should be in good health and should not have any major mendelian disorders, major malformations or genetic disorders or any significant familial disease with a major genetic component or life-threatening disorders[16]. Ultimately, ASRM recommends that clinical outcomes for each treatment cycle should be recorded and permanent records about each donor be maintained to serve as a future medical resource for any offspring produced. The storage of this information is relevant to the recipients as it relates to other information-sharing decisions they may make[17]. In addition, IVF programs, egg donor agencies and sperm banks should honor the original disclosure parameters described in the agreement between the donor and recipients unless the donor and recipients mutually agree to disclose more (or less) than originally agreed upon or the donor and adult child agree to additional disclosure[18]. If a party, however, has initially refused future contact after a full discussion with medical, psychological and legal professionals, then legally and ethically she or he should not be contacted to reconsider the decision. Recontact is ethically complicated if the clinic or agency failed to provide adequate time for and access to legal and psychological counseling when the party made the future contact decision.

Issues surrounding informed consent within egg donation programs have recently been spotlighted in the clinical genetics branch of medicine. As advances in molecular genetics continue to evolve including the use of comparative genomic hybridization microarrays and other genomic technology such as high-density single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping microarrays, researchers and clinicians will be able to further identify individuals who are genetically susceptible or at an increased risk for a particular disease[19]. In some cases, obstetrical outcome may ultimately reveal a medical condition in a live-born that is attributed to the donor. Further genetic testing may be required and could have consequences including (1) re-contacting the donor at a later date for tissue typing; (2) request for organ donation or bone marrow transplant; and (3) disclosure and involvement to family members beyond the individual donor and theoretically, making accurate assessment only possible if multiple members of the donor’s family participate in testing[20,21]. Furthermore, advances in molecular genetics can lead to the molecular diagnosis and recognition of many genetic conditions from stored blood samples of gamete donors, heel sticks obtained through newborn screening programs and cord blood samples from the offspring. This may allow researchers and clinicians to recognize genetic profiles that may identify certain treatable or preventable diseases in gamete donors and their offspring. This has significant implications for the donor’s reproductive choices, health concerns for her children (if she has any) and even has financial considerations impacting the donor’s ability to secure health insurance or other medical treatments. The development of these new testing techniques, as well as the advancement of reproductive medicine, has progressed so swiftly that clinical and legal policies have struggled to integrate the informed consent, future re-contact, and legal, ethical and psychological aspects of the testing modalities.

Overall, it is generally agreed upon in the medical and research community that any pre-treatment assessment and testing results should be given to its research participants[22-24]. The American National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute task group recently recommended reporting results to study participants when (1) the associated risk for the disease is significant; (2) the disease has important health implications to the participants; (3) proven therapeutic or preventive measures are available; and (4) the establishment of laboratory validity has been performed[25].

Similar to the American National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, ASRM endorses full disclosure when genetic information or medical information comes to light resulting from their donation or in offspring that may affect their health or the health of their own family, though only upon request. As such, while ASRM endorses outcome disclosure, they acknowledge that disclosure of any genetic testing is based on each clinic’s policy of appraisal including unexpected information and that it is ethically acceptable for programs not to inform donors of cycle outcomes as it may violate recipients’ privacy rights if disclosed involuntarily. This presents a unique challenge, as these recommendations for full disclosure typically are not addressed by programs because they fail to take into account the individual preferences of gamete donors and recipients, where both more often express a desire for anonymity and non-disclosure, including no future re-contact regarding the use of 3rd party gametes[26]. It has also come to light that legal obligations created in the donor-recipient agreement may have disclosure and re-contact provisions that more often are dramatically different from either the agency or sperm bank commitment or the IVF clinic’s informed consent to treatment document (personal experience of the authors). Sometimes people participate in independent donor registries, in contravention to previous agreements. Rarely are clinics or storage facilities informed of these changes.

Several studies have assessed research participant’s desire to know study results. A survey of donor preferences in a Japanese population-based genetic epidemiologic cohort study (n = 1857) revealed that while the majority of donors wished to be re-contacted and receive disclosure of information, 13% of respondents (15% female and 10% males) did not want to be re-contacted[27]. A Swedish study surveyed general attitudes toward tissue donation for a hypothetical bio-bank study where collection of blood and tissue samples had been collected, and approximately 10% of subjects did not want to know if they had any genetic pre-disposition to disease under any circumstance, while merely 55% only desired the results if an effective treatment or prevention was available[28]. Other studies consistently reveal that a proportion of subjects do not want disclosure of genetic testing. Vernon et al[29] revealed 10% of patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer who had given blood samples did not want to know the results of the genetic testing and data from the Puget Sound Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results registry also suggested some colorectal cancer patients and their relatives were not interested in identifying and discussing their genetic status[30].

With respect to third party reproduction, only recently, Lindheim et al[11] reported views from both oocyte recipients and donors. Oocyte recipients generally were amenable to disclosure to their oocyte donor of pregnancy outcome (88%), contact for a medical emergency (74%), and disclosure of medical or genetic condition to oocyte donors (88%), which was consistent over time from the ante-to post-partum periods. In contrast, at their initial interview, oocyte donors were also generally amenable to contact for a medical emergency (83%), and disclosure of a medical or genetic outcome (83%), however, they were reticent to obtain the knowledge of pregnancy outcomes (31%). For those oocyte donors who underwent the whole process including oocyte retrieval, there was a more general reticence to receiving information regarding a medical or genetic condition (93% vs 38%)[11].

For those who do not want disclosure or future contact, this raises ethical issues often seen in genetics and medicine which not only include issues related to the duty and obligation to re-contact and disclose the inadvertent or unanticipated results, but also weighing against the recipient and donor’s unique individual preferences and contractual obligations for disclosure. Some have argued that the possibility of knowing unanticipated testing results and adverse outcomes raises the responsibility to further explore and understand the reticence of research candidates (and in this case donors and recipients) to disclose or become informed. It is also important to appreciate that attitudes including level of comfort and disclosure towards assisted reproduction are likely to change over time, and this should be acknowledged to patients at the onset of the process.

With respect to re-contact, the International Ethics Committee of the Human Genome Project strongly suggests that research participants’ right not to know genetic results must be secured prior to the study[31]. Again, the issue of re-contacting donors could be harmful because this may be considered an invasion of privacy as well as a breach of contract had she not previously agreed to be “re-contacted”. This creates a conundrum because the donor might have changed her mind about receiving the information, however, she cannot consider whether or not she has changed her desire to know because to re-contact her to inquire would be a legal and ethical violation of her earlier consent.

Further complicating the picture is that the future holds the real potential for consumers to have access to Direct to Consumer (DTC) genetic testing, including oocyte recipients who may obtain archival DNA from an oocyte donor-conceived child and have it tested by a private company, outside of any legal, psychological or medical safeguards or prior commitments not to conduct such testing. It has become increasingly challenging, if not impossible, to inform a patient of all potential genetic information that could be acquired and the consequences of that information, yet DTC possibilities should be disclosed to the donor. Paramount to this information is the accuracy of such testing and correct interpretation of test results, and the meaning of the information to the affected person. The risk is magnified as there is an increasing number of DTC and over-the-counter testing combined with greater consumer acceptance of such genetic testing. As recipients are informed about the ability to store DNA samples from the donor for future testing or even store cord blood for future testing, the complexity of gathering, testing, validating, disclosing and explaining such information is compounded. Many regulators, including the States of California and New York, have called for additional oversight and ethical guidelines for DTC testing[32,33]. Furthermore, the legal and communication needs, including informed consent and legal agreements for all involved parties documenting each party’s commitment to each other, demand a broader and more integrated approach.

The future is here, where a well thought out procedure and protocol is needed at the ART program level to ascertain and secure the individual preferences of gamete donors and recipients for future re-contact at the onset of any gamete donation cycle. This should include the involvement of a mental health professional and a genetic counselor or geneticist to assist in the policy development of the informed consent procedure since they possess a knowledge base of patient concerns and anxieties[34-36]. Moreover, it should include the involvement of reproductive attorneys to assist with policy development and implementation. Implicit in this protocol is informed consent, which involves more than simply signing a form of authorization for a procedure in order to protect providers from legal risks. Informed consent must include provisions for the future identification of tests, results and outcomes, prior to any research or outcomes regarding the right to disclose genetic results, which needs to be clearly identified to truly respect a patient’s future autonomy[37,38].

Understanding the preferences regarding contact and disclosure for both donors and recipients impacts ART Programs’ recruitment, screening and consent practices, legal agreements between donors and donor agencies and between donors and recipients, and policies for ART Programs. Oocyte donor programs, both in-house and agencies, should establish policies regarding disclosures and re-contact procedures. It underscores the delicate balance between parental interests and desires in creating their family and anticipated interests of future children including curiosity to know their genetic heritage.

REPRODUCTIVE TOURISM-EXILE

Increasingly, couples are traveling from their country of residence to another in order to receive specific reproductive treatments not allowed, not available, or too costly in their own country[39]. This practice has been coined “reproductive tourism”, though others have argued that this term is both inaccurate and inappropriate, as it suggests that couples are traveling for pleasure and alternatively have suggested the term “reproductive exile”[40]. In contrast, couples and individuals in the United States travel to other countries to take advantage of significantly reduced costs of egg donors and gestational carriers. Many times, the initial benefit of reduced compensation is offset by higher legal costs and anxiety when parentage orders and passports are denied by the foreign country.

The main reasons for reproductive tourism-exile have been eloquently summarized including: (1) treatment that is prohibited in the country of origin because the application is considered ethically unacceptable (use of donor gametes or sex selection for non-medical reasons); (2) patients possess characteristics that are considered to make them unfit for parenthood (postmenopausal intended mother, advanced age of the couple, unmarried, or same sex couple); (3) the technique is considered medically unsafe (oocyte freezing, cytoplasmic transfer); (4) treatment is not available because of lack of expertise (preimplantation genetic diagnosis); (5) the waiting lists are too long (donor oocytes); or (6) costs (fees) are exorbitantly high[39].

Since the infamous case of Diana Blood, who transferred the sperm of her deceased husband from the United Kingdom to Belgium in order to be inseminated, most instances of reproductive tourism-exile are performed for women who require donor oocyte or donor sperm. At the time Belgium had no laws on assisted reproduction, the Belgian register on assisted reproduction for 1999 indicated that 30% of patients receiving IVF and 60% of all oocyte donor recipients were foreigners[41]. Belgium has since changed its laws[42]. French patients cross the border because they want to increase their chances of success by avoiding the obligatory embryo freezing after oocyte donation or because they do not want to comply with the “personalized anonymity” rule, which precludes the use of a known oocyte donor[43]. For preimplantation genetic diagnosis in Belgium, half of all couples are from Germany and France as a result of legal or practical restrictions in their countries or origin[44]. Spain attracts oocyte recipients from all over Europe because of the long waiting lists in other countries.

International gestational surrogacy

International gestational surrogacy is an area of increasing concern. A surrogate’s services are used in the following situations: (1) Foreign Nationals as intended parents (IPs) using a US surrogate who delivers a child in the US; (2) US-IPs using a surrogate who resides and delivers in a foreign country; or (3) US-IPs using a non-US citizen surrogate who illegally resides and delivers in the US. Similar questions for each scenario that have been raised include: (1) Who will the law define as the legal parents (2) Will the law protect the child’s welfare and best interests (3) Which country’s laws apply to the surrogate arrangement and the finalization of parental rights

In many cases, this has led to inconsistent and unfortunate outcomes where children have been defined as orphans or genetic parents’ rights were not recognized[45-48]. Each scenario discussed below has its own unique legal and ethical concerns.

US-IPs using a foreign gestational surrogate

Ethical concerns regarding global fertility arrangements have focused on issues of exploitation. Very recently a US attorney pleaded guilty to felony charges related to international surrogacy activities. She arranged to have non-US women pose as “surrogates”, and then once they were pregnant, matched them with US couples through deceit and misrepresentation to both the prospective parents and the courts. While women are being “employed” as surrogates, with global economic disparity, the question that arises is, “are women being cohered into being surrogates” Fully informed consent with sufficient counseling and support can be a challenge for domestic surrogacy arrangements, however, adding a cross-cultural component and language differences further add to the risk that parties are inadequately informed and counseled about the process.

It is also ethically complicated to define what the parameters of coercion are. Some would argue, for example, that even if a foreign surrogate receives better medical care during her pregnancy than the typical pregnancy in her country, the process is still unethical because the care is less than what a US surrogate would receive. On the other hand, if surrogacy is the best opportunity to earn money for a foreign woman given her other employment options, is it wrong even though she is being paid a third of what a US surrogate would be paid In other words, while payment appears to be inherently coercive and an offensive commodification, should women not be allowed to provide for themselves and their children in this way, especially if the alternative is worse

Another significant issue is the protection of the foreign surrogate’s health and her human rights. Many concerns have been raised regarding the process of foreign surrogate screening. Other concerns surround relinquishment of the child and whether surrogates are given access to legal protection(s) and follow-up counsel if future concerns or issues arise regarding their surrogate arrangement.

Conversely, issues that raise concern for US-IPs include adequate disclosure regarding the health and pregnancy status of the foreign surrogate, which may in part be due to cultural and language barriers that may not satisfy the needs of the IPs. While in the US failure to disclose this information may provide a legal cause of action[49], it may not be actionable in another country. In addition, US-IP’s may also not be aware of another country’s statutes used to recognize or deny their parental rights. IP’s use of US adoption laws could be problematic if courts rely on the relinquishment statements of the surrogate provided only through affidavits instead of being present during court proceedings. With these complexities, each party must be adequately informed as US-IPs are more inclined to be short sighted, focusing on reduced medical costs and simply hoping to avoid potential expensive legal complications.

Foreign National-IPs using a US gestational surrogate

While there are no residency requirements for finalization of parentage proceedings when a child is born in the US, navigation through the US legal system is critical for foreign nationals to finalize their parental rights and to deal with issues related to foreign or dual citizenship. Even if foreign nationals navigate the US legal system, it is not a guarantee that their county will accept a US court order determining parentage. Ensuring adequate health insurance coverage for the surrogate is necessary to not only complete medical-psychological assessment at the outset, but to ensure that the Foreign National-IPs pay for antepartum, postpartum and neonatal care if needed regardless of court petitions to determine parentage or custody. It can be difficult and costly to secure insurance coverage for the newborn(s), but it is not routinely secured as part of Foreign National-IP surrogate arrangements. This can result in exorbitant bills that the Foreign National IP may not feel obligated to pay, particularly in the treatment for premature infants. This places an enormous burden on the US health care system.

US-IPs using a foreign gestational surrogate who illegally resides and delivers in US

Sometimes non-US citizens serve as surrogates to US-IPs including relatives or undocumented workers hired by IPs “under the radar” as a domestic or hourly laborer. This relationship may raise a number of quandaries. Generally the US-IPs provide room and board during the pregnancy. This has the potential for the surrogate to feel isolated and vulnerable as the constant scrutiny of the IPs can create a potentially abusive situation. The surrogate may not be able to effectively communicate to others including the obstetrician or seek protection for fear of deportation. The intended parents may have falsely offered citizenship, or the surrogate may be misinformed about the legal status of the baby and how it impacts her and her family.

For the intended parents, the surrogate is a flight risk where she could return to her country of origin making it extremely difficult to enforce the relinquishment of the child per the terms of the contract. The carrier may be uninsured, placing additional burdens on the health care system.

International issues of ART have forced courts to make decisions in the absence of laws, international treaties and even a global consensus about the appropriateness of the transnational fertility market. In contrast, international adoption law (The Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption) has been ratified by many nations setting legal and ethical standards for adopting children around the world[50].

Given the prevalence of reproductive tourism-exile, the ethical issues can best be addressed with international cooperation. Establishment of guidelines presumes that the international community can agree on shared values in protecting participants and promoting the health and welfare of children.

CONCLUSION

These are but a few of the plethora of difficult questions we are confronted with surrounding third party reproduction. This complex process requires consideration of broad social, ethical, and legal issues. Each potentially impacts prospective parents, their offspring, egg donors and gestational carriers, and society. The advances and increased utilization of this technology has and will continue to create additional legal and policy challenges not only in the US but abroad as well. Reproductive law responds to medical uses of technology and underscores the importance of a closed circle of communication connecting reproductive professionals. There is an ever-increasing need for clarity and consistency in the area of reproductive law and willingness of medical professionals to follow policy guidance from a broader community both domestically and internationally. Collaborative efforts between reproductive health professionals allows for a seamless dialogue between reproductive law and medicine, which in the end is essential to meet the needs of all involved parties, and most importantly the needs of children conceived through ART.

Peer reviewer: Eduardo C Lau, Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Wisconsin, Children’s Research Institute, TBRC Room C2450, 8701 Watertown Plank Road, Milwaukee, WI 53226, United States

S- Editor Xiong L L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM