Peer-review started: August 1, 2015

First decision: November 6, 2015

Revised: December 13, 2015

Accepted: January 5, 2016

Article in press: January 7, 2016

Published online: February 6, 2016

AIM: To review the characteristics of hematological malignancies in tropical areas, and to focus on the specific difficulties regarding their management.

METHODS: This is a retrospective narrative review of cases of patients with hematological malignancies. All medical files of patients with malignant disease whose treatment was coordinated by the Hemato-Oncology service of the Cayenne Hospital in French Guiana between the 1st of January 2010 and the 31st of December 2012 were reviewed. Clinical data were extracted from the medical files and included: Demographic data, comorbidities, serological status for human immunodeficiency virus, human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV1), hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections, cytology and pathology diagnoses, disease extension, treatment, organization of disease management, and follow-up. The subgroup of patients with hematological malignancies and virus-related malignancies were reviewed. Cases involving patients with Kaposi sarcoma, and information on solid tumor occurrence in virus-infected patients in the whole patient population were included. Since the data were rendered anonymous, no informed consent was obtained from the patients for this retrospective analysis. Data were compiled using EXCEL® software, and the data presentation is descriptive only. The references search was guided by the nature of the data and discussion.

RESULTS: In total, the clinical files of 594 patients (pts) were reviewed. Hematological malignancies were observed in 87 patients, and Kaposi sarcoma in 2 patients. In total, 70 patients had a viral infection, and 34 of these also had hematological malignancies. The hematological diagnoses were: Multiple myeloma in 27 pts, lymphoma (L) in 43 pts, myeloproliferative disorders in 17 pts and Kaposi sarcoma in two patients. The spectrum of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) was: Burkitt L (1 pt), follicular L (5 pts), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (5 pts), high-grade NHL (9 pts), mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue NHL (4 pts), T-cell lymphoma (4 pts), Adult T-cell lymphoma-leukemia (ATL)/lymphoma/leukemia (12 pts); three patients had Hodgkin disease. The spectrum of myeloproliferative diseases was: Chronic myelogenous leukemia (8 pts), thrombocytemia (5 pts) and acute leukemia (4 pts). There were no polycythemia vera, myelosclerosis, and myelodysplastic diseases. This appears to be due to bias in the recruitment process. The most important observations were: The specificity of HTLV1- related ATL malignancies, and the high incidence of virus infections in patients with hematological malignancies. Further, we noted several limitations regarding the treatment and organization of disease management. These were not related to the health care organization, but were due to a lack of board-certified hemato-oncology specialists, a lack of access to diagnostic tools (e.g., cytogenetic and molecular diagnosis, imaging techniques), the unavailability of radiotherapy, and the physical distance from mainland France. Yet the geography and cultures of the country also contributed to the encountered difficulties. These same limitations are seen in tropical countries with low and intermediate household incomes, but they are amplified by economic, social, and cultural issues. Thus, there is often little access to diagnostic procedures, adequate clinical management, and an unavailability of suitable medical treatments. Programs have been developed to establish centers of excellence, training in pathology diagnosis, and to provide free access to treatment.

CONCLUSION: Management of hematological malignancies in tropical areas requires particular skills regarding specific features of these diseases and in terms of the affected populations, as well as solid public health policies.

Core tip: Management of hematological malignancies is guided by very specialized and up to date guidelines that are based on the biology of the diseases. An important proportion of these diseases are related to viral infections, and this is particularly so in tropical areas. Based on a narrative review of 87 cases of patients managed in French Guiana, we provide an overview of the most important characteristics of these hematological diseases (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus and human T-lymphotropic virus 1 related diseases), the limitations regarding management (e.g., board-certified specialists, pathology labs, imaging techniques, radiotherapy), and possible solutions to improve quality (e.g., centers of excellence, training programs in pathology). These observations may be more broadly relevant in the setting of countries with low and intermediate household incomes.

- Citation: Droz JP, Bianco L, Cenciu B, Forgues M, Santa F, Fayette J, Couppié P. Retrospective study of a cohort of adult patients with hematological malignancies in a tropical area. World J Hematol 2016; 5(1): 37-50

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6204/full/v5/i1/37.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5315/wjh.v5.i1.37

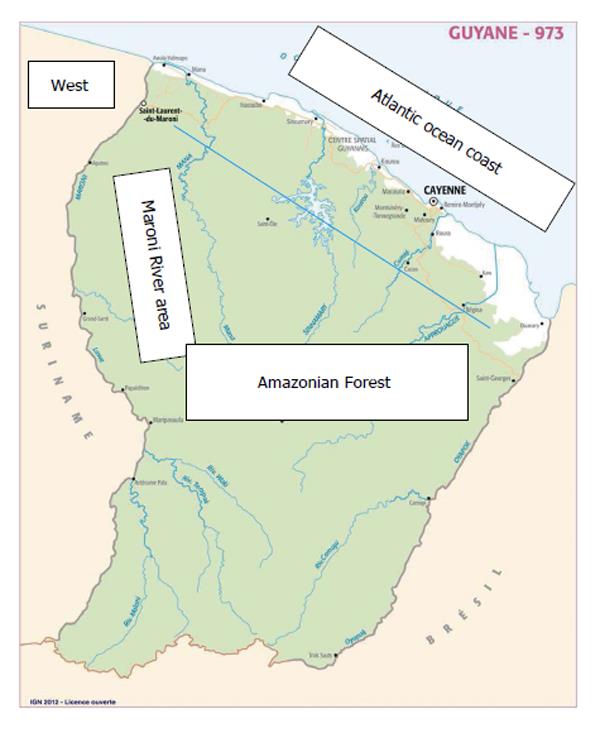

French Guiana is an Overseas Department (ZIP code: 9700 Guiana) and a Region of France. The political, administrative, and health care organizations are the same as in mainland France. The territory covers 85000 km2, 95% of which is Amazonian forest. The climate is equatorial. The official population is 229000 inhabitants[1], but there are approximately 40000 illegal immigrants. The population is located primarily along the Atlantic shore. There are three major cities: Cayenne and surrounding area (127000 inhabitants), Saint-Laurent du Maroni (33700 inhabitants) and Kourou (25900 inhabitants). The remainder of the population reside in small villages (2000 to 8000 inhabitants in the general vicinity of the village, and sometimes as little as a few dozen people in the village itself). The majority of the population and associated economic activities are concentrated on the Atlantic Ocean Coast (which is 450 km in length and 30 km wide). The population of French Guiana is expanding[2]. It was 115000 in 1990 and was 229000 at the last census in 2009. In 2040, the population is projected to be 480000 to 650000[3]. The median age is 28 years. The fertility rate is 3.57 children/woman. The annual population growth rate is 3.9%. The percentage of people 70 years of age or older is 1.5%. The annual birth-rate is 30.4 per 1000 and the annual death-rate is 3.7 per 1000[2]. Economic activity is based on agriculture (0.8%), panning for gold, construction (13.7%), and tertiary activities represented mainly by administrative and military entities (85.5%).The rate of unemployment is high[2]. The population of French Guiana is diverse and comprised of Guianese and French West Indies creoles (40%), metropolitans (10%), Haitians (10%), Brazilians (10%), Surinamese (10%), Chinese, Guyanese, and two specific indigenous populations groups: Native Americans (around 5000-8000 individuals) and Bushinengue (“Noirs marrons” or maroons) (around 15000 individuals). There are major cultural differences between these various ethnic groups.

There are two public hospitals (in Cayenne, and Saint-Laurent du Maroni) and one Red-Cross hospital in Kourou. The Cayenne regional hospital is a university hospital within the framework of the University of the French West Indies - Guiana. The most developed and active medical services are (1) related to obstetrics and pediatrics; and (2) emergency, intensive care unit (ICU), management of trauma and transport of wounded patients. Eighteen health care centers are linked with the Cayenne Hospital, and they are located throughout French Guiana. Figure 1 provides a map of French Guiana.

This study is part of a larger retrospective study of 594 adult patients with cancer who were managed by the Hematology-Oncology unit of the Cayenne Hospital during 2010 to 2012. The objective was to highlight the major problems regarding management of adult hematological malignancies in a tropical region with a European health organization that was subject to specific limitations due to the tropical setting and the distance from mainland France. These are: An absence of conventional and ICU hematological services, unavailability of board-certified specialists (except monthly visits by specialists from the Centre Léon-Bérard in Lyon, France), a lack of specific labs and radiotherapy on the one hand, as well as the prevalence of tropical infectious diseases and problems due to cultural diversity on the other hand. In this study we have also provided insights regarding virus related malignancies [human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV1), and a focus on hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus (HBV/HCV) lymphoproliferative disorders]. In the Discussion section, we strived to extend the observations made in French Guiana to problems encountered in other tropical countries in the developing world.

For the purpose of this study, we retrospectively reviewed the clinical charts of all adult patients who were managed by the Hematology-Oncology unit of the Department of Amazonian Health of Cayenne Hospital from the 1st of January 2010 until the 31st of December 2012.

The data collected were: Date of birth, age, gender, home address, place of birth, description and number of comorbidities, cancer type, extension (local, regional, metastatic or specific classification), HIV, HTLV1 and HBV/HCV serological status (no information on EBV infection status), treatment and management in mainland France or the French West Indies. Cultural identity (e.g., Bushinengue or Native American) was annotated if the patient mentioned the fact during the course of the clinical management. Neither the cytology nor pathology examinations were reviewed centrally. The pathology reports were used as provided in the medical files. Examinations were performed at the Cayenne Hospital and in various laboratories in France. Details of biological characteristics of the malignancies (e.g., immunochemistry and immunophenotypes, molecular biology examinations) were rarely available. Available examinations are provided in the Table 1. We restricted the analysis to descriptions; no comparison test was used. The files were rendered anonymous. Complete remission (CR) status, the date of the most recent news and follow-up (FU) duration in years, as well as the clinical status were recorded. Unfortunately, the majority of patients were lost to FU. Clinical files were summarized in an EXCEL® data base. The results were derived using features of the EXCEL® software.

| Diagnosis | No. of patients | |

| Examinations available in French Guiana | ||

| Myeloma | 27 | Complete blood count with cytology |

| Lymphoma (43 patients) | Bone-marrow aspiration and biopsy | |

| Burkitt | 1 | Common limited immunophenotypes |

| Follicular | 5 | Standard blood chemistry |

| CLL | 5 | LDH and β2-microglobulin |

| High-grade B-NHL | 9 | Standard immunological studies |

| MALT NHL | 4 | Immunoelectrophoresis (blood and urine) |

| T-NHL | 4 | Serological testing for HIV, HTLV1, HBV, HCV, EBV, as well as PCR/RT-PCR for these viruses, HHV8, HPV and the majority of infectious diseases (opportunistic or not) |

| Standard bone X-rays | ||

| CT scan | ||

| MRI | ||

| Examinations not available in French Guiana | ||

| ATL/lymphoma | 10 | PET scan |

| ATL/leukemia | 2 | Complete immunophenotypes |

| Hodgkin | 3 | Genetic testing |

| Myeloproliferative diseases (17 patients) | ||

| CML | 8 | |

| Thrombocytemia | 5 | |

| Acute leukemia | 4 | |

| Specific HIV-related entity (2 patients) | ||

| Kaposi | 2 |

We did not obtain individual informed consent; we used current hospital medical files; all the data presented were rendered anonymous and the chance of patient identification was extremely low.

A reference search was conducted using PUBMED with the key words: “French Guiana; cancer; neoplasm; Kaposi; lymphoma; leukemia, multiple myeloma, myeloproliferative diseases”. However, we also reviewed the literature relating to recommendations published for hematological malignancies (National Cancer Centers Network - NCCN[4-7], French Hematological Recommendations[8]). Epidemiological data were derived from Globocan 2012[9,10] and from the French National Cancer Institute report of 2014[11]. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

In total, we reviewed 594 medical files of patients with malignancies, of whom 87 had hematological malignancies. We also included two cases of HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma. For the purpose of having a review of systemic virus infections in these patients, we specifically analyzed the group of patients with an HIV, HTLV1, HBV or HCV positive serological status. The entire 594 patient study was the subject of a thesis[12] for an MD degree (Bianco L), and it was reviewed and approved by the University of French Guiana and West Indies Medical School Institutional Review Board.

This article provides a narrative review of general information for the entire 89 patient cohort, and specific information on the various groups of diseases.

There were 50 men and 49 women; the median age was 46 years (ranging from 18-85 years of age). The majority of patients (61) lived in the Cayenne area; 15 patients lived in the Western part of French Guiana (i.e., Saint-Laurent du Maroni and Mana areas) and 6 patients lived in the Maroni River area (refer to Figure 1). In 6 cases, the home address was unknown. The place of birth was the Cayenne area for 19 patients, the Western part of French Guiana for 10 patients, the Maroni River area for 6 patients, unknown for 25 patients, and countries other than French Guiana for 29 patients (Surinam 9, the French West Indies 5, Haiti 4, Brazil 3, mainland France 3, and other foreign countries for 5 patients). Comorbidities were frequent in this population of young patients: 28 had one comorbidity, 11 had 2, 8 had 3, and one had 4, while 40 had no comorbidities (for one patient, comorbidities remained unknown). The most frequent comorbidities were hypertension (25 patients), diabetes (16 patients), congestive heart failure (5 patients), lung diseases (asthma and chronic obstructive bronchopathy in 2 and 3 patients, respectively), stroke in 4 patients, and dementia and psychosis in one patient for each of these mental conditions. Two patients had chronic renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min). Tuberculosis, malaria, and leprosy were present in one patient for each of these conditions. One patient had an albinism, one had cirrhosis related to chronic HBV hepatitis, and three patients suffered of drepanocytosis.

The HIV, HTLV1, and HBV/HBC serological status were unknown in 31, 40, and 34 patients, respectively. Nine out of 58 patients had an HIV positive serological status and viremia, four of whom had been treated and had achieved infection control. Fifteen out of 49 patients had HTLV1 positive serological status. Ten out of 55 patients had a positive hepatitis virus status: 8 were HBV+/HCV- and two were HBV-/HCV+. One patient had a positive serological status for both HIV and HTLV1. One patient had previously had prostate cancer.

The hematological malignancy diagnoses are detailed in the Table 1.

Twenty-seven patients were managed during this period: 10 men and 17 women. MGUS was not included in this series. Median age was 62 years (ranging from 44 to 85 years of age). The number of comorbidities was 0, 1, 2 and 3 in 10, 10, 4 and 3 patients, respectively. There were 10 cases of hypertensions, 5 involving diabetes, one with drepanocytosis and one with chronic renal insufficiency. One patient had a solitary plasmocytoma, IgGκ, in the sphenoid bone of the skull base, 4 patients had smoldering myeloma and 22 patients had active myeloma, 8 of whom were eligible for high-dose chemotherapy (HDCT). The monoclonal component was IgAλ in 3, IgAκ in 5, IgGλ in 2 and IgGκ in 10 patients, while this information was not available for 6 patients. The Durie-Salmon stage[13] was IA in 4 patients, IIIA in 7, IIIB in 7 and not available for 8 patients. One patient was HIV+, but had achieved disease control following treatment, while one patient had an HBV+ serological status. The patient with a plasmocytoma had a partial resection of the tumor and radiotherapy followed by adjuvant Bortezomib treatment for 6 mo. Patients with smoldering myeloma were followed without being given a specific treatment, and one of them died two years later. Treatment and evolution of the 22 patients with active myeloma are shown in the Table 2. All these patients received biphosphonates treatment and supportive care.

| No. | Gender | Age | Ig | Stage | Regimen 1 | Regimen 2 | Regimen 3 | FU (yr) |

| 1 | M | 65 | IgAλ | IIIB | Bortezomib + DEXA | Melphalan DEXA | 0 | 6 |

| 2 | F | 60 | IgGκ | NA | Bortezomib + DEXA | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 3 | M | 66 | IgAκ | NA | Bortezomib + DEXA | 0 | 0 | < 1 |

| 4 | F | 77 | IgAκ | IIIB | Thalidomide + Melphalan | Melphalan + DEXA | 0 | < 1 |

| 5 | F | 80 | NA | IIIA | Thalidomide | 0 | 0 | < 1 |

| 6 | M | 56 | IgAκ | IIIB | Thalidomide + DEXA | Thalidomide + Melphalan | 0 | 2 |

| 7 | F | 71 | IgGκ | NA | Bortezomib + DEXA | Thalidomide | 0 | 4 |

| 8 | F | 85 | IgGκ | IA | Melphalan + DEXA | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 9 | F | 62 | IgAλ | NA | Melphalan + DEXA | Bortezomib + DEXA | 0 | 7+ |

| 10 | M | 83 | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | < 1 |

| 11 | F | 65 | IgGλ | IIIA | Bortezomib + DEXA Thalidomide | VAD | 0 | 11 |

| 12 | F | 81 | NA | IIIB | Thalidomide + Melphalan + DEXA | 0 | 0 | < 1 |

| 13 | M | 57 | IgGκ | NA | Bortezomib | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 14 | F | 69 | IgGκ | IIIA | Melphalan + Thalidomide, | Lenalidomide | 0 | 4 |

| 15 | F | 59 | IgGκ | IIIA | Bortezomib + DEXA + Thalidomide | HDCT | 0 | 3+ |

| 16 | M | 44 | IgAκ | IIIB | Bortezomib + DEXA | HDCT | 0 | 3 |

| 17 | F | 60 | IgGκ | IIIB | DEXA+ Melphalan + Thalidomide | HDCT | Lenalidomide | 6 |

| 18 | M | 52 | IgGλ | IIIA | Bortezomib + DEXA | HDCT | 0 | 2 |

| 19 | F | 61 | IgGκ | IIIB | Bortezomib + DEXA + Thalidomide | HDCT | 0 | 2 |

| 20 | M | 62 | NA | NA | Bortezomib + DEXA | HDCT | Lenalidomide | 2 |

| 21 | M | 53 | IgAκ | IIIA | VAD | HDCT | 0 | 12 |

| 22 | F | 55 | IgGκ | IIIA | Bortezomib + DEXA + Thalidomide | HDCT | 0 | < 1 |

Eleven patients were treated in mainland France. These were the eight patients who had high-dose chemotherapy (one cycle of high-dose Melphalan) and autologous bone-marrow support (ABMS), the patient with plasmocytoma, and two other patients.

Forty-three patients had lymphomas, including adult T-cell lymphoma-leukemia (ATL)/lymphoma/leukemia and Hodgkin disease. There were 28 men and 15 women; median age was 50 years (ranging from 18 to 84 years of age).

Clinical entities are summarized in the Table 2.

Five patients had chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). They were four men and one woman, aged 46, 50, 60, 62 and 70 years. The Binet stage[14] was A, B, C in 2, 1 and 2 patients, respectively. One patient had auto-immune hemolytic anemia (a Bushinengue patient with stage C disease). Patients had standard immunophenotyping (Matutes score)[15], but none of these patients underwent fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and molecular analysis. One patient had an HTLV1 positive serological status. Two patients were only monitored (less than 1 and 6 years FU, respectively), one received Chlorambucil (less than 1 year FU). Two patients received Fludarabine and Rituximab (3 years FU), one of whom eventually received R-CHOP (5 years FU).

Five patients had follicular lymphoma. They were 2 men and 3 women; median age 55 years (ranging from 40 to 66 years of age). Two patients had HBV positive serological status, one of whom had post hepatitis cirrhosis. One patient was HIV+, although he had received treatment and achieved disease control. The Ann Arbor stage[16] was: IIAE (1 patient, E: Breast), IIIA (2 patients), IV (2 patients). All of these patients were treated in mainland France. Four patients received R-CHOP and one Rituximab only.

Four patients (3 men and one woman; aged 42, 68, 69, 84 years) had mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas. Two patients had gastric MALT, Ann Arbor stages IIE and IV (one patient had a positive HCV and HTLV1 serological status) and two patients had skin MALT, both stage IV (one of whom had a positive serological HTLV1 status). All patients received Rituximab, on its own for one patient, and combined with Fludarabine for two patients, with CHOP either as first line or second line, depending on the patient. Three patients reached a CR status and one attained stable disease. One patient died after 2 years of disease progression, another patient died after 10 years of cardiac heart failure, and two patients underwent 4 and 9 years FU.

A 46-year-old male immigrant from Senegal had a high-risk Burkitt lymphoma. He had a prior record of malaria and a controlled HIV infection. He was transferred to Paris for treatment where he received R-COPADEM-CYVE regimen chemotherapy[17]. This individual went into complete remission (at 1 year of FU).

High-grade B-cell lymphomas were observed in 9 patients. For 3 patients the data was incomplete, as full pathology and immunophenotyping were not available[18,19].

DLBCL was observed in 9 patients. Five patients were treated in the West French Indies or mainland France. Two patients were of Bushinengue descent, and one was a Native American. Disease extension was not available in 3 patients. The Ann Arbor stage was IIA and IIIB in one patient each, IV in 4 patients. Treatment modalities were available for 7 patients: 6 patients received R-CHOP[20] and one R-ACVBP[21]. Two patients had HDCT and ABMS (2 CR) and two patients required DHAP[22] salvage chemotherapy regimen (one CR). In total there were 4 cases of CR (5, 10, 10, and less than 1 year FU), 4 other patients had less than 1 year FU, and one patient died after 2 years. The case of this latter patient is notable. He was a 53-year-old male of Bushinengue descent who lived along the Maroni River and who had an albinism. He had multiple exereses of basal-cell carcinoma of the skin. Serological status for HIV, HTLV1, HBV and HCV were all negative. He had a stage IIIB DLBCL and received R-CHOP that was complicated by neutropenic fever. He received R-DHAP after disease progression, and died of disease progression after 2 years of this treatment.

Two women and one man, aged 18, 44 and 51 years, had Hodgkin disease. The histological type was nodular sclerosis in all 3 patients. The Ann Arbor stages were IIA (2 patients) and IIIA. The 51-year-old male had been treated for HIV infection, which was under control, and a renal insufficiency. All three patients received ABVD regimen[23] of chemotherapy. The patient with stage IIA disease was referred to mainland France for radiotherapy. All of them entered into CR status, but were then soon lost to FU.

Four patients has T-cell lymphomas, all of them had very uncommon clinical history with unfortunately a lot of missing information.

Two men, aged 40 and 75 years, had T-cell lymphoma. Both received CHOP regimen chemotherapy. The 75 year old patient had a response to treatment, but he was lost to FU after 5 years. Unfortunately, disease extension was not available. The other patient was a 40-year-old of Bushinengue descent and residing in the Maroni River area. He had an active untreated and uncontrolled HIV infection. HTLV1 and HBV/HCV serological status were negative. The Ann Arbor stage was IV with osteolytic bone involvement and hypercalcemia. The patient received CHOP chemotherapy regimen. He died, however, of progressive disease after 4 mo.

One patient had a very complex disease, for which many of the data were not available. This individual (a 49-year-old male) had respiratory insufficiency and hyper eosinophilia. Serological status was negative, and he had no parasitic disease. The lung biopsy demonstrated a bronchocentric granulomatosis. The blood cytology and in the medullary aspirate showed a monoclonal T-cell proliferation. Nonetheless the precise phenotype is not available. Various treatment sequences were administered. He was lost to FU after 10 years.

The last patient was a 21-year-old male from the Maroni River area and he was of Bushinengue descent, with an Ann Arbor stage IV lymphoma which was classified as precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. He received R-CHOP and entered into CR, and relapsed and died one year later. Nevertheless the retrospective study of the pathological report (liver biopsy) shows a profile of large-cell anaplastic T-cell lymphoma (ALK-).

Nine patients had ATL/lymphoma and two patients ATL/leukemia. There were 6 women and 5 men; their median age was 46 years. Nine patients were of Bushinengue descent, eight of whom lived in the Western part or in the Maroni River area. Four patients had hypertension; two had diabetes, one suffered from drepanocytosis. One patient had a serologically positive HBV+HCV- infection. One patient had a treated and controlled HIV infection. All patients had serologically positive HTLV1 infection. It is noteworthy that four patients had aggressive Strongyloides stercoralis GI infections. Three patients were treated in Paris and one in the Netherlands. The patient treatments and evolution are shown in the Table 3. To date, no patient has died, while two patients are in CR.

| No. | Gender | Age | Stage | Tumor sites | Regimen 1 | Regimen 2 | Regimen 3 | FU |

| ATL/lymphoma | ||||||||

| 1 | M | 28 | NA | L/Z + P-IFN + oral ETO | CHOP | 0 | 2 | |

| 2 | M | 34 | IV | L/Z + P-IFN | CHOP | DHAP | 3 | |

| 3 | M | 38 | NA | L/Z + P-IFN | CHOP | DHAP | 1 | |

| 4 | F | 46 | III | Abdomen, Ca2+ | CHOP | VBl | 1 | |

| 5 | M | 49 | IV | CHOP | DHAP | < 1 | ||

| 6 | M | 49 | IV | Colon, CNS | L/Z + P-IFN | CHOP | IT-MTX | < 1 |

| 7 | F | 51 | IE | Nasal, sinus | 0 | CHOP | 0 | < 1 |

| 8 | F | 58 | IIA | L/Z + P-IFN | CHOP | 0 | 3 | |

| 9 | F | 62 | NA | L/Z + P-IFN + ETO oral | CHOP | 0 | 5 | |

| 10 | M | 42 | IV | Ca2+ | R-CHOP | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| ATL/leukemia | ||||||||

| 10 | M | 41 | - | Liver, cavum | L/Z + P-IFN | CHOP | 0 | < 1 |

| 11 | F | 47 | - | L/Z + P-IFN + oral ETO | CHOP | 0 | 4 |

One patient had a singular history. He was a 42-year-old man from the Maroni River area and of Bushinengue descent with a stage IV lymphoma (lymph nodes and bone osteolytic lesions). He had hypercalcemia. This patient had serologically positive untreated HIV and HTLV1 infections. He had also a retinitis and CNS toxoplasmosis. The disease was initially diagnosed as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The patient received two cycles of R-CHOP, but contact with this patient was lost soon thereafter, thereby precluding FU. But the diagnosis was reviewed and changed to an ATL/lymphoma.

Chronic myelogenous leukemia: Eight patients had chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). They were 5 men and 3 women, with a median age of 51 years (ranging from 37 to 82 years of age). Aside from the older patients, none of them had significant comorbidities. The diagnosis was established by cytology, and the presence of Ph1 by FISH. Three patients underwent bcr-abl transcript analysis, one of whom lacked Ph1 [he was bcr-abl(-), but JAK2+], and two after developing resistance to Imatinib. The possibility of bcr-abl point mutations was, however, not addressed. The older patient, who was bcr-abl(-), received hydroxyurea. Three patients received first line hydroxyurea, followed by Imatinib and then Dasatinib. Three patients received first-line Imatinib, and then Dasatinib, while one patient received Dasatinib first-line. None of the patients were transferred to mainland France, and none died of the disease after a median FU of 3 years. None of them was considered for allogenic bone marrow transplantation.

Essential thrombocytemia: Three women and two men, aged 34, 41, 44, 49, 54 years, had essential thrombocytemia. One patient had hypertension and another had hypertension, arteritis and stroke, while the younger patient had a portal thrombosis. Three patients had a JAK6V617F mutation. This mutation did not occur in two patients, one of whom was bcr-abl(-). These two patients had no evaluation of MPL mutation. One patient received Anagrelide, and all of these patients were treated with hydroxyurea. They were alive after 3-4 years of FU.

Acute leukemia: Three men, one woman, aged 22, 39, 46, 54 years were diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia. All of them were transferred to Paris for treatment. According to the FAB classification[24] there were one LAM5 and three LAM3: One of them was promyelocytic RARα+, another had a Flt3 duplication with t(15;17). Patients were treated according to standard regimens[8]: The patient with LAM5 had an allogenic bone-marrow transplantation; patients with LAM3 received Idarubicin, all-trans-retinoic acid, and arsenic trioxide. Patients entered into CR, and they were free of disease at less than 1, 1, 2 and 5 years of FU.

The distribution of tumor types in patients infected with viruses is shown in the Table 4.

| Virus | Hematological malignancies | Solid tumors | Total |

| HIV | 9 | 19 | 28 |

| HTLV1 | 15 | 4 | 19 |

| HBV | 8 | 10 | 18 |

| HCV | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Total | 34 | 36 | 70 |

HIV infection: Nine patients had an HIV infection in this series, 4 with treated and controlled disease. Five patients had lymphomas (one follicular lymphoma, two DLBCL, one ATL/lymphoma, one Burkitt lymphoma). The other patients either had myeloma or Hodgkin disease.

Two patients had the HIV-related malignancy Kaposi sarcoma. They were two men who were aged 38 and 54 years. One had an uncontrolled HIV infection. He had serous involvement by the disease, and although he received liposomal Doxorubicin, the disease progressed and this patient was soon lost to FU. The other patient, an immigrant from Haiti, had a treated and controlled HIV infection, and he had involvement of the colon, lymph nodes and particularly the skin of both legs. He received liposomal Doxorubicin and experienced stable disease. He was alive with the disease after 3 years of FU.

Of the total of 28 patients who were HIV+ in the series of 594 patients, 9 were described above. The tumor types in the 19 other patients were: Prostate, gastric (3 each), cervix, breast, lung, head and neck (2 each), penile, kidney, pancreas, esophageal and colon cancers (one each).

HTLV1 infection: Nineteen of the 594 patients had a positive serological status. Fifteen patients had hematological malignancies, of which 12 were ATL/lymphoma/leukemia; two MALT non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), one CLL. The four other patients either had colon, liver, prostate or kidney cancer.

HBV infection: Of the entire 594 patient cohort, 18 patients had a positive serological status: 8 had hematological malignancies while the others had various tumor types comprised of breast (3), liver (2), gastric (2), cervix, prostate and head and neck cancer (one each).

HCV infection: Of the entire 594 patient cohort, 5 patients had a positive serological status: 2 had hematological malignancies and the others had either liver (2), or lung cancer (1).

This study reports on 87 patients with hematological malignancies (and two with Kaposi sarcomas) who were managed during a three-year period at the main hospital in French Guiana. However the study scale is small, but it provides several interesting insights that are of considerable relevance in terms of the provision of medical care. First of all, there is the effect of bias. There are biases of recruitment of patients in the series: Patients may have been managed in the two other hospitals of the territory. This may not have occurred so much in Kourou (which is only 50 km from Cayenne), but rather in Saint-Laurent du Maroni, which is 250 km far from Cayenne. It is noteworthy that Saint-Laurent is the most substantial city (around 50-70000 inhabitants) of the Western part of French Guiana, of the Bushinengue area and also of both banks of the Maroni River (French and Surinamese), as Paramaribo, Surinam’s capital is 150 km west of Saint-Laurent. Moreover, there are many illegal immigrants, but since the border control is 100 km down the road running from Saint-Laurent to Cayenne, many patients are managed at the local hospital. Other biases are the fact that myelodysplastic syndromes are either managed by other hospital wards, or they are misdiagnosed; an unknown proportion of patients are directly referred to mainland France; and lastly, an unknown proportion of patients from the Western and Maroni River areas are certainly not diagnosed due to the absence of robust medical network.

Other interesting insights are the gap between the needs for hematological disease management and the facilities that are available. This aspect can be equated with countries in tropical areas that have low and intermediate household incomes. Lastly, this series shows the importance of infections in the occurrence of some hematological malignancies to be reviewed.

In this series, out of 594 patients with malignancy, hematological malignancies occurred in 87 patients (i.e., 14.5%).

The incidence of hematological malignancies could, however, not be measured. We are cognizant of the fact that it is scientifically inexact as it is an approximate assessment of the prevalence of hematological diseases which were accounted for in the period from 2010 to 2012. In 2008, in mainland France, the incidence of hematological malignancies relative to solid tumors was found to be 6.5%[25]. The comparative morbidity figures for solid tumors in mainland France (2005) vs French Guiana (2003-2009) was determined to be 1.30 and 1.31 for men and women, respectively[26]. The incidence of cancers therefore seems lower in French Guiana than in mainland France. GLOBOCAN 2012 incidence data[9,10] show that French Guiana has a global incidence of cancer in keeping with other northern and North-Western parts of South America (137.5/100000), but lower than in Brazil, Argentina, Chile and specially Uruguay (where the incidence is the highest, and at a level that is similar to Western countries). The incidence of hematological malignancies in French Guiana is similar to that of mainland France, but higher than in the majority of South American countries, at 6.5/100000 for leukemia (as in Ecuador), 2.4/100000 for multiple myeloma (as in Surinam) and 7.0/100000 for NHL (as in Colombia and Uruguay).

Patients with multiple myeloma had the same median age as in mainland France, while there was a slight predominance among women. The precise staging procedures at the initial diagnosis were not always fully available in the medical files. Nevertheless, with the exception of the cytogenetics of plasma cells[5], the most important criteria were available. The most important genetic abnormalities should be in regard to chromosomal 13q deletion, and detection by FISH of t(4;14), t(14;16), and del17p. These are poor prognostic factors. The international staging system is nonetheless used in clinical practice[27]. The majority of patients benefited from proteasome inhibitors, and Thalidomide. Eight out of 22 patients had high-dose Melphalan with ABMS. The conditions to indicate HDCT and ABMS are based on response to first-line treatment[28] and practical opportunity to perform HDCT. Treating multiple myeloma is hence not a problem in the setting of this organization. In patients not eligible to HDCT, new regimens including targeted drugs are more active than Melphalan plus prednisone regimen[29], and a Bortezomib-DEXA regimen seems to have the same activity as the three drug regimens (with Thalidomide or Melphalan)[30].

The pathology diagnosis of lymphoma was established by different pathologists in French Guiana, the French West Indies or mainland France. The standard procedure first comprised morphological analysis, followed by a standard immunophenotyping panel with at least CD20, CD79a for B-cell malignancies and the same negative readout with CD3, CD5 for T-cell malignancies. Depending on the first screening and the capabilities of the laboratory, other antigens were also tested. Precise information regarding the pathology procedures and classification was not generally available. Since 2010, the biopsy samples have been referred to one of the pathology reference centers affiliated with the French National Cancer Institute (LYMPHOPATH network). Clinical staging of lymphomas (both NHL and Hodgkin Disease) used the Ann Arbor classification, as originally reported[16], because the lack of access to TEP-scanning did not allow use of the Lugano staging system[31].

Patients with CLL exhibited classical features of the disease. There were diagnosed using an immunophenotyping panel that allowed application of the Matutes score[15].

Staging of the patients was established according to the Binet classification[15]. None of the patients had FISH to screen for a del(11q) or del(17p), which plays an important role in the identification of specific treatments, nor Ig mutational profile and expression of protein ZAP70, which are highly relevant for the prognosis[8]. Patients therefore received treatment according to their clinical status. Thus, the patient with auto-immune hemolytic anemia received R-CHOP regimen. The treatment eventually conformed to recognized standards.

Patients with follicular lymphomas received a standard work-up, including a bone-marrow aspirate and biopsy. They were staged according to the Ann Arbor classification. It is noteworthy that these patients were all referred to mainland France for treatment. There is no specific explanation for this, except that two of them were from a metropolitan area. All of them nonetheless benefited from extensive work-up, and they received Rituximab with or without a CHOP regimen of chemotherapy for extensive or progressive disease. This is standard disease management. Two patients had an HBV infection, which has not been reported to be linked with the occurrence of follicular lymphoma[32]. HIV infection also does not seem to be related to this NHL type.

Two patients had gastric MALT lymphoma. Information regarding infection by Helicobacter pylori was not available, and FISH t(11;18) was not performed. One of these patients had positive HCV and HTLV1 serological status (stage IIE). Unfortunately, no information on splenic involvement was available, as it has been described in splenic marginal zone lymphoma related to HCV infection[33]. Two patients had skin MALT lymphoma. Information on infection by Borrelia burgdorferi was not available. One of these patients had a positive serological HTLV1 status. The staging procedure was standard. With gastric MALT lymphoma, no information on Helicobacter pylori treatment was known, but all of them received induction immunotherapy (Rituximab). In three cases, associated chemotherapy was given because of stage IV disease.

The patient with Burkitt lymphoma had standard current characteristics: Malaria[34], African descent, and HIV infection[35-37]. He was treated in keeping with the best treatment standards in Paris[17].

High-grade lymphomas were diagnosed according to morphological aspects and standard minimal immunophenotyping. The Ann Arbor stage was used, but the International Index was not available[38]. Five patients were transferred to mainland France and therefore had a complete diagnostic and clinical work-up. When the information was available, these patients nonetheless received standard chemotherapy regimens[39] with Rituximab. Two patients with stage IV disease, who responded to conventional chemotherapy, received HDCT and ABMS. The two Bushinengue patients with specific disease were not transferred to mainland France. This may have been due to the absence of coverage for their health expenses. The native American patient was transferred to Paris for treatment. These individuals are usually French citizens, and they hence have the appropriate level of social security coverage. DLBCL belongs to the spectrum of hematological malignancies related to HIV[40], but that are unrelated to HTLV1 and HBV. The precise diagnosis of albinism was not done, but it is likely to have been a type 2 oculocutaneous albinism. This disease does not seem to increase the risk of lymphoma (although this patient did experience repeated basal cell carcinomas).

Two patients had large cell T-cells lymphoma. Unfortunately, information regarding the expression of ALK was not available[6]. The response to CHOP was in keeping with the diagnosis of anaplastic large cell lymphoma. It is very rare to come across a T-cell lymphoma in a patient with an untreated uncontrolled HIV infection. A misdiagnosis must hence be suspected.

The three patients with Hodgkin disease did not have exceptional characteristics, and they were treated in keeping with the standard treatment[4]. One patient had a controlled HIV infection, and this might have been involved in the mechanism of the disease, although it unexpectedly exhibited a nodular sclerosis pattern, which is less frequent than mixed cellularity in this setting[41].

Eleven patients had ATL/lymphoma/leukemia, as defined by the Shimoyama classification[42]. The serological status was established by the ELISA method and confirmed by Western blot. When results from these assays were inconclusive, HTLV1 PCR was performed (at the Pasteur Institute). All patients had been infected by HTLV1. It is noteworthy that 9 of them were Bushinengue. This is a very well-recognized observation in French Guiana[43]. The Bushinengue population has a high prevalence of this infection[44], which is seen extensively in children[45] as the virus is transmitted from the mother by breast feeding[46,47]. Clinical work-up was in agreement with recommendations[6]. Four patients had Strongyloides GI involvement, which is often observed with this disease[48]. Patients received Ivermectin or Abendazole treatments. Patients also received standard treatment focused on retrovirus control, as a combination of Lamivudin + Zidovudin and Peg-interferon α-2a[49]. It also included standard chemotherapy regimens, such as CHOP[50] as first-line and DHAP as second-line treatments[6]. Five patients were treated in mainland France. This may present a difficult socio-cultural problem for the patients who live in the Maroni River area, and is an issue which will be discussed below. Due to cultural reasons, the majority of patients were lost to FU.

The eight patients with CML were managed in a very conventional manner. Unfortunately, they were underdiagnosed and potentially undertreated. Apart from the cytological diagnosis and Ph1 FISH, the initial work-up ought to have included analysis of bcr-abl transcripts and screening for JAK2, CALR and MPL mutations, as well as a complete karyotyping[7]. No patient underwent mutational analysis for TKI second-line resistance so as to evaluate further indication of Nilotinib, Bosutinib, Ponatinib and Omacetaxine. Criteria for cytogenetic[51] and molecular[52] responses were not performed. Therefore, patients received Hydroxyurea and/or first-line Imatinib, and Dasatinib when they progressed. The profile of the patients did not fit with conditions for treatment by allogenic bone-marrow transplantation. Furthermore, organizing a prolonged stay in mainland France to select the indication and to perform the procedure is fraught with difficulties[53].

Surprisingly, we observed five cases of thrombocytemia. The same criticism can be made in terms of the lack of a complete work-up to at least eliminate secondary thrombocytopenia[8]. These diseases are however not specific to this tropical region.

The failure to encounter cases of polycythemia vera, myelofibrosis and myelodysplastic syndromes is certainly due to a bias in the recruitment process; such as the patients not being referred to the unit, not been diagnosed or, in some cases being directly referred to mainland France by their treating physician.

Lastly, four patients had acute myeloid leukemia. All of them were transferred within two or three days after diagnosis to a hematology unit in Paris by medical transport using the daily flight between Cayenne and Paris. This may present a substantial bias since these four patients were adults who had achieved CR status, while some patients may have been transferred only to return directly home with progressive disease, or they may even have died while in Paris. Further, some patients may have been children who were not managed in the hematology-oncology unit, while some patients may have died prior to diagnosis due to the distance from their residence to the hospital (for example, a patient who lives in the Maroni River area, with no doctor nearby, could face a two days trip by canoe to Saint-Laurent du Maroni, and then at least another day for administrative processing and a day for transfer to Cayenne…).

The importance of viral infections in this patient population from this tropical region has been reported in various epidemiological studies[32]. Half of the virally-infected patients presented with hematological malignancies, while only 14% of the entire patient population of the series exhibited hematological malignancies. HIV is the most common viral infection. Hematological B-cell malignancies correspond with being afflicted with AIDS[40]. Two patients had very aggressive Kaposi sarcomas, which are typically encountered with HIV infected patients[54]. In this series, HBV serum positive status is often encountered, but there is no evidence in the literature that this virus could be involved in the occurrence of hematological malignancies. HCV has however been implicated in the occurrence of marginal B-cell lymphomas[33]. The small number of positive patients does, however, not allow such a conclusion to be drawn from this series.

Conversely HTLV1 infection is quite common. Moreover, screening for HTLV1 infection is part of the diagnosis of ATL/lymphoma/leukemia. Although serological positivity in French Guiana is quite high, this does not necessarily mean that affected individuals are going to develop hematological malignancies. Indeed, the majority of patients are highly unlikely to suffer any adverse consequences from this infection.

The Table 1 aims to give an indication of what is available for the diagnosis of patients with hematological malignancies. Thus, basic examinations are reasonably available, while some of the more in depth examinations may be obtained at a metropolitan laboratory. What is most relevant, however, is to have one or two board-certified (hemato-oncology) specialists available to manage the patient, specify the work-up, monitor patient progression, and get feedback from colleagues in mainland France regarding the patient cases. Lastly, they can recommend the transfer of patients for specialized management. This is not currently the case. At present, this is done by monthly 3 d visits of specialists from Centre Léon-Bérard in Lyon, and weekly contact with the tumor board by video conferencing. The current daily management is performed by two generalist practitioners. The issues encountered require a medico-scientific view of the situation. A very strong relationship between the Hemato-Oncology unit in Cayenne and a center of excellence in mainland France is paramount in providing these patients access to optimal treatment. Two useful logistical entities can be developed on site: Extension of the laboratory of pathology, and the implementation of TEP-scanning. Conversely, implementation of radiotherapy is not feasible to date.

Thus, in this regard French Guiana is, in fact, fully linked with mainland France, and can be seen as being independent of its neighboring countries Surinam and Brazil. Indeed, there are no transportation means to readily reach urban centers in Brazil. Although there actually is a bridge across the Oyapock River (at a distance of 200 km from Cayenne), there is no paved road to Belem (600 km). Moreover, the health care system in Brazil is mainly private. Only illegal Brazilian immigrants could benefit from having their disease managed in Brazil. Cooperation with Surinam could be easier to organize, as a Surinamese company operates flights between Cayenne and Paramaribo. It is also feasible to cover this 400 km distance by motor vehicle. Such an arrangement would however also require a genuine willingness to cooperate at a political level, and this has not been scheduled to date.

Social aspects are very important considerations. The majority of patients, even illegal immigrants, are covered by one or other of the various national health insurance systems. In French Guiana 60%, 28%, 12% of the population is covered by the national health insurance, the universal social insurance and the emergency medical help, respectively. This means that the administrative management for these patients is extremely time consuming and needs multiple players, including the police, social security, social services, etc.

Cultural aspects are also very important. The recommendations produced by the French National Cancer Institute for cancer patient management have been implemented, and they match international criteria. This nonetheless only applies to a small proportion of patients, being mainly the residents of metropolitan areas and a small proportion of Guianese and French Caribbean creoles. Even in this population the word “cancer” is taboo. This applies even more to Bushinengue and native Americans patients. In general, knowledge of the illness is expressed clearly (using the word “cancer”). The problem lies more with the significance of such a diagnosis, particularly when it comes to interpretation of the cause of the disease, which is often assigned to evil spirits or somebody who has cast a spell[55]. A great proportion of patients therefore seek advice from a wizard or medicine man. This does not preclude the possibility of conventional treatment, although it does generally delay it. These aspects are inadequately scrutinized and overcome by cancer patients. More progress has been made for patients with HIV infections[56]. An important aspect is that it is often thought that Bushinengue patients who become ill should return to their own village to die. This view hence tends to fully preclude taking the risk that the patient might die elsewhere, such as in a hospital, possible far away, such as in mainland France. The view is often that, should this occur, it would cast a pronounced spell on the deceased’s lineage. It is therefore important that transcultural mediation is developed, as has been done for HIV patients[56].

This series summarizes some of the problems that are encountered in other tropical countries that have low and intermediate household[57]. Unlike French Guiana, these countries do not have the option, however, of providing disease management in mainland France. In these countries the most severe shortcomings are the lack of a sufficient number of board-certified specialists, the equipment and skill of pathology laboratories, the lack of access to new drugs, and particularly targeted drugs (mainly due to cost), as well as the lack of imaging and radiotherapy equipment. Various initiatives have been instigated to implement centers of excellence[58] and programs to provide access to new drugs, as done for Imatinib in CML and GIST[59,60]. The implementation of radiotherapy is also an important initiative, as it makes one of the most efficient therapeutic means more accessible[61]. Another important initiative is the implementation of diagnostic pathology learning programs. These are promoted by the International Network Cancer treatment and Research[62]. Initiative have been promoted for surgery training[63]. Training and research programs are priorities of international organizations[64,65].

In conclusion the specificity of tropical hematology (and oncology) is important: Firstly, in terms of gaining knowledge and understanding of disease mechanisms, and, secondly for decision making and organization of the management of these malignancies in the tropical areas. The latter requires particular skills relating to the specificity of these diseases and of the affected populations, as well as solid public health policies. Finally the study reflects the problems the hematologists face in the daily practice in this area.

The authors greatly thank Mrs. Sophie Domingues for skillful editing of the manuscript.

This study is part of a larger retrospective study of 594 adult patients with cancer who were managed by the Hematology-Oncology unit of the Cayenne Hospital during 2010 to 2012.

The objective was to highlight the major problems regarding management of adult hematological malignancies in a tropical region with a European health organization that was subject to specific limitations due to the tropical setting and the distance from mainland France.

This aspect can be equated with countries in tropical areas that have low and intermediate household incomes. Lastly, this series shows the importance of infections in the occurrence of some hematological malignancies to be reviewed.

In conclusion the specificity of tropical hematology (and oncology) is important: Firstly, in terms of gaining knowledge and understanding of disease mechanisms, and, secondly for decision making and organization of the management of these malignancies in the tropical areas. The latter requires particular skills relating to the specificity of these diseases and of the affected populations, as well as solid public health policies.

It is an interesting retrospective study regarding hematological malignancies in french guiana. The study also reflects the problems the hematologists face in the daily practice.

P- Reviewer: Diamantidis MD, Nosaka T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | INSEE guyane. Legal population in French Guiana in 2011. Available from: http://www.insee.fr/fr/ppp/bases-de-donnees/recensement/populations-legales/default.asp. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | INSEE guyane. Population evolution and structure in French Guiana. Available from: http://www.insee.fr/fr/bases-de-donnees/default.asp?page=statistiques-locales.htm. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | INSEE guyane. Population demographic projection in 2040 in French Guiana. Available from: http://www.insee.fr/guyane. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Hodgkin Lymphomas. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhl.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Multiple Myeloma. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloma.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Non Hodgkin Lymphomas. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhl.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cml.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | French Society of Hematology. Hematology malignancies guidelines. Available from: http://sfh.hematologie.net/hematolo/UserFiles/File/REFERENTIEL%20COMPLET%20VERSION%20FINALE%20SFH20082009(1).pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | International Agency for Research on Cancer. Globocan 2012: estimated incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/Map.aspx. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JW, Comber H, Forman D, Bray F. Reprint of: Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1201-1202. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | French National Cancer Institute. Report of activity 2014. Third cancer plan. Available from: http://www.e-cancer.fr/Expertises-et-publications/Catalogue-des-publications/Rapport-d-activite-2014-de-l-Institut-national-du-cancer-2014-premiere-annee-de-mise-en-oeuvre-du-nouveau-Plan-cancer. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Bianco L. Pratique de la cancérologie en milieu équatorial: étude rétrospective sur trois années (2010-2012). Available from: http://theseimg.fr/1/sites/default/files/Th%C3%A8se%20finalis%C3%A9e%20L%20BIANCO_0.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Durie BG, Salmon SE. A clinical staging system for multiple myeloma. Correlation of measured myeloma cell mass with presenting clinical features, response to treatment, and survival. Cancer. 1975;36:842-854. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Binet JL, Auquier A, Dighiero G, Chastang C, Piguet H, Goasguen J, Vaugier G, Potron G, Colona P, Oberling F. A new prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukemia derived from a multivariate survival analysis. Cancer. 1981;48:198-206. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Matutes E, Owusu-Ankomah K, Morilla R, Garcia Marco J, Houlihan A, Que TH, Catovsky D. The immunological profile of B-cell disorders and proposal of a scoring system for the diagnosis of CLL. Leukemia. 1994;8:1640-1645. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Rosenberg SA. Validity of the Ann Arbor staging classification for the non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Cancer Treat Rep. 1977;61:1023-1027. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Patte C, Auperin A, Michon J, Behrendt H, Leverger G, Frappaz D, Lutz P, Coze C, Perel Y, Raphaël M. The Société Française d’Oncologie Pédiatrique LMB89 protocol: highly effective multiagent chemotherapy tailored to the tumor burden and initial response in 561 unselected children with B-cell lymphomas and L3 leukemia. Blood. 2001;97:3370-3379. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Lin P, Jones D, Dorfman DM, Medeiros LJ. Precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma: a predominantly extranodal tumor with low propensity for leukemic involvement. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1480-1490. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011;117:5019-5032. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1268] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1356] [Article Influence: 104.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, Lefort S, Marit G, Macro M, Sebban C. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood. 2010;116:2040-2045. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 884] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1029] [Article Influence: 73.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ketterer N, Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Fermé C, Brière J, Casasnovas O, Bologna S, Christian B, Connerotte T, Récher C. Phase III study of ACVBP versus ACVBP plus rituximab for patients with localized low-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (LNH03-1B). Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1032-1037. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Philip T, Chauvin F, Armitage J, Bron D, Hagenbeek A, Biron P, Spitzer G, Velasquez W, Weisenburger DD, Fernandez-Ranada J. Parma international protocol: pilot study of DHAP followed by involved-field radiotherapy and BEAC with autologous bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1991;77:1587-1592. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Santoro A, Bonadonna G, Valagussa P, Zucali R, Viviani S, Villani F, Pagnoni AM, Bonfante V, Musumeci R, Crippa F. Long-term results of combined chemotherapy-radiotherapy approach in Hodgkin’s disease: superiority of ABVD plus radiotherapy versus MOPP plus radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:27-37. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, Sultan C. Proposals for the classification of the acute leukaemias. French-American-British (FAB) co-operative group. Br J Haematol. 1976;33:451-458. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Colonna M, Mitton N, Bossard N, Belot A, Grosclaude P. Total and partial cancer prevalence in the adult French population in 2008. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:153. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cancer Registry of French Guiana. Available from: http://www.ars.guyane.sante.fr/Registre-des-cancers-de-Guyane.96173.0.html. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Greipp PR, San Miguel J, Durie BG, Crowley JJ, Barlogie B, Bladé J, Boccadoro M, Child JA, Avet-Loiseau H, Kyle RA. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3412-3420. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1802] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1883] [Article Influence: 99.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cavo M, Rajkumar SV, Palumbo A, Moreau P, Orlowski R, Bladé J, Sezer O, Ludwig H, Dimopoulos MA, Attal M. International Myeloma Working Group consensus approach to the treatment of multiple myeloma patients who are candidates for autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:6063-6073. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 226] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Harousseau JL, Palumbo A, Richardson PG, Schlag R, Dimopoulos MA, Shpilberg O, Kropff M, Kentos A, Cavo M, Golenkov A. Superior outcomes associated with complete response in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients treated with nonintensive therapy: analysis of the phase 3 VISTA study of bortezomib plus melphalan-prednisone versus melphalan-prednisone. Blood. 2010;116:3743-3750. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 90] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Niesvizky R, Flinn IW, Rifkin R, Gabrail N, Charu V, Clowney B, Essell J, Gaffar Y, Warr T, Neuwirth R. Community-Based Phase IIIB Trial of Three UPFRONT Bortezomib-Based Myeloma Regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3921-3929. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 119] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, Lister TA. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3059-3068. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2850] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3186] [Article Influence: 318.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, Plummer M. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:607-615. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1583] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1710] [Article Influence: 142.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Suarez F, Lortholary O, Hermine O, Lecuit M. Infection-associated lymphomas derived from marginal zone B cells: a model of antigen-driven lymphoproliferation. Blood. 2006;107:3034-3044. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 293] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chêne A, Donati D, Guerreiro-Cacais AO, Levitsky V, Chen Q, Falk KI, Orem J, Kironde F, Wahlgren M, Bejarano MT. A molecular link between malaria and Epstein-Barr virus reactivation. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e80. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 132] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Gopal S, Achenbach CJ, Yanik EL, Dittmer DP, Eron JJ, Engels EA. Reply to P. De Paoli et al. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3079. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Gopal S, Achenbach CJ, Yanik EL, Dittmer DP, Eron JJ, Engels EA. Moving forward in HIV-associated cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:876-880. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | De Paoli P, Carbone A. Pathogenesis of HIV-associated cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3078. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:987-994. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3971] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4038] [Article Influence: 130.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Molina TJ, Canioni D, Copie-Bergman C, Recher C, Brière J, Haioun C, Berger F, Fermé C, Copin MC, Casasnovas O. Young patients with non-germinal center B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma benefit from intensified chemotherapy with ACVBP plus rituximab compared with CHOP plus rituximab: analysis of data from the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte/lymphoma study association phase III trial LNH 03-2B. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3996-4003. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Goedert JJ, Coté TR, Virgo P, Scoppa SM, Kingma DW, Gail MH, Jaffe ES, Biggar RJ. Spectrum of AIDS-associated malignant disorders. Lancet. 1998;351:1833-1839. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. | Biggar RJ, Jaffe ES, Goedert JJ, Chaturvedi A, Pfeiffer R, Engels EA. Hodgkin lymphoma and immunodeficiency in persons with HIV/AIDS. Blood. 2006;108:3786-3791. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 280] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Shimoyama M. Diagnostic criteria and classification of clinical subtypes of adult T-cell leukaemia-lymphoma. A report from the Lymphoma Study Group (1984-87). Br J Haematol. 1991;79:428-437. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | Gessain A, Calender A, Strobel M, Lefait-Robin R, de Thé G. [High prevalence of antiHTLV-1 antibodies in the Boni, an ethnic group of African origin isolated in French Guiana since the 18th century]. C R Acad Sci III. 1984;299:351-353. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 44. | Plancoulaine S, Buigues RP, Murphy EL, van Beveren M, Pouliquen JF, Joubert M, Rémy F, Tuppin P, Tortevoye P, de Thé G. Demographic and familial characteristics of HTLV-1 infection among an isolated, highly endemic population of African origin in French Guiana. Int J Cancer. 1998;76:331-336. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Plancoulaine S, Gessain A, Joubert M, Tortevoye P, Jeanne I, Talarmin A, de Thé G, Abel L. Detection of a major gene predisposing to human T lymphotropic virus type I infection in children among an endemic population of African origin. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:405-412. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Ureta-Vidal A, Angelin-Duclos C, Tortevoye P, Murphy E, Lepère JF, Buigues RP, Jolly N, Joubert M, Carles G, Pouliquen JF. Mother-to-child transmission of human T-cell-leukemia/lymphoma virus type I: implication of high antiviral antibody titer and high proviral load in carrier mothers. Int J Cancer. 1999;82:832-836. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Tortevoye P, Tuppin P, Carles G, Peneau C, Gessain A. Comparative trends of seroprevalence and seroincidence rates of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I and human immunodeficiency virus 1 in pregnant women of various ethnic groups sharing the same environment in French Guiana. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:560-565. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 48. | Carvalho EM, Da Fonseca Porto A. Epidemiological and clinical interaction between HTLV-1 and Strongyloides stercoralis. Parasite Immunol. 2004;26:487-497. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 166] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Bazarbachi A, Plumelle Y, Carlos Ramos J, Tortevoye P, Otrock Z, Taylor G, Gessain A, Harrington W, Panelatti G, Hermine O. Meta-analysis on the use of zidovudine and interferon-alfa in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma showing improved survival in the leukemic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4177-4183. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Besson C, Panelatti G, Delaunay C, Gonin C, Brebion A, Hermine O, Plumelle Y. Treatment of adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma by CHOP followed by therapy with antinucleosides, alpha interferon and oral etoposide. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:2275-2279. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, Gathmann I, Baccarani M, Cervantes F, Cornelissen JJ, Fischer T, Hochhaus A, Hughes T. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:994-1004. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2530] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2420] [Article Influence: 115.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Hughes T, Deininger M, Hochhaus A, Branford S, Radich J, Kaeda J, Baccarani M, Cortes J, Cross NC, Druker BJ. Monitoring CML patients responding to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: review and recommendations for harmonizing current methodology for detecting BCR-ABL transcripts and kinase domain mutations and for expressing results. Blood. 2006;108:28-37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 905] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 862] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Müller LP, Müller-Tidow C. The indications for allogeneic stem cell transplantation in myeloid malignancies. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:262-270. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Mbulaiteye SM, Biggar RJ, Goedert JJ, Engels EA. Pleural and peritoneal lymphoma among people with AIDS in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:418-421. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 55. | Vernon D. Bakuu: possessing spirits of witchcraft on the Tapanahony. Utrecht: Nieuwe West-Indische GIds 1980; 1-38. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 56. | Vernon D. Adapting information for Maroons in French Guyana. AIDS Health Promot Exch. 1993;4-7. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 57. | Vento S. Cancer control in Africa: which priorities? Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:277-279. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Ngoma TA. Cancer control in the tropical areas, access to expensive treatments, and ethical considerations. In: Droz JP, Carme B, Couppié P, Nacher M, Thiéblemont C: Tropical Hemato-oncology. Springer Publishing International Schwitzerland 2015; 25-35. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 59. | Kingham TP, Alatise OI, Vanderpuye V, Casper C, Abantanga FA, Kamara TB, Olopade OI, Habeebu M, Abdulkareem FB, Denny L. Treatment of cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e158-e167. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 164] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Tekinturhan E, Audureau E, Tavolacci MP, Garcia-Gonzalez P, Ladner J, Saba J. Improving access to care in low and middle-income countries: institutional factors related to enrollment and patient outcome in a cancer drug access program. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:304. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Barton MB, Frommer M, Shafiq J. Role of radiotherapy in cancer control in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:584-595. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 196] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Naresh KN, Raphael M, Ayers L, Hurwitz N, Calbi V, Rogena E, Sayed S, Sherman O, Ibrahim HA, Lazzi S. Lymphomas in sub-Saharan Africa--what can we learn and how can we help in improving diagnosis, managing patients and fostering translational research? Br J Haematol. 2011;154:696-703. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Grigorian A, Sicklick JK, Kingham TP. International surgical residency electives: a collaborative effort from trainees to surgeons working in low- and middle-income countries. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:694-700. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | African Organisation for research and Training in Cancer (AORTIC). Available from: http://www.aortic-africa.org/. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 65. | Cancer Association of South Africa (CANSA). Available from: http://www.cansa.org.za/. [Cited in This Article: ] |