Published online Nov 27, 2013. doi: 10.5313/wja.v2.i3.30

Revised: May 3, 2013

Accepted: June 8, 2013

Published online: November 27, 2013

Foreign body aspiration is a worldwide health problem which often results in life threatening complications. Tracheostomy tube fracture resulting in airway obstruction is a serious condition which has been reported in the medical literature. We report a rare case of a tracheostomy obturator fractured and lodged in tracheobronchial tree in a patient who presented with acute respiratory distress. Rigid or flexible bronchoscopy is frequently necessary for the diagnosis as well as the treatment. In adults, removal of the foreign body can be attempted during a diagnostic examination with a fiberoptic bronchoscope under lignocaine local infiltration with sedation, which may help to avoid any further invasive procedures. Flexible bronchoscopy should always be considered in foreign body aspiration. A periodic review of the techniques of tracheostomy care, including timely check-ups for signs of wear and tear, can possibly eliminate such avoidable late complications.

Core tip: Foreign body aspiration is often a serious medical condition that demands timely recognition and prompt action. Delayed diagnosis and subsequent delayed treatment is associated with serious and sometimes life threatening complications. We describe a case of acute respiratory distress following aspiration of part of the obturator of a tracheostomy tube during a routine change of the tracheostomy tube.

- Citation: Afzal M, Al Mutairi H, Chaudhary I. Fractured tracheostomy tube obturator: A rare cause of respiratory distress in a tracheostomized patient. World J Anesthesiol 2013; 2(3): 30-32

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6182/full/v2/i3/30.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5313/wja.v2.i3.30

Foreign body aspiration is often a serious medical condition that demands timely recognition and prompt action. Delayed diagnosis and subsequent delayed treatment is associated with serious and sometimes fatal complications[1]. In adults, however, foreign body aspiration can be tolerated and remain undetected for a long time. We describe a case in which part of the tracheostomy obturator was broken and migrated into the tracheobronchial tree, resulting in acute respiratory distress.

A tracheostomized 68-year-old male known to have hypertension and diabetes presented at our emergency room with progressive acute respiratory distress. During a routine change of the tracheostomy tube, medical staff noticed that the tracheostomy obturator was fractured and had migrated into the trachea. The bronchoscopic removal in a referral hospital was unsuccessful. Therefore, the patient was referred to our hospital for further management. Past medical history revealed that the patient had had a cardiac arrest 3 mo earlier due to myocardial ischemia and was successfully resuscitated. After prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation, the patient remained on a ventilator for 3 wk. Thus, the tracheostomy was done after the few unsuccessful attempts of weaning from the ventilator. Pre anesthesia evaluation revealed electrocardiography (ECG) showing periodical supra ventricular tachycardia with antero-lateral ischemic changes, whereas the echocardiography showed a moderately dilated left ventricle with severely impaired systolic function, with an ejection fraction of 10%-25%.

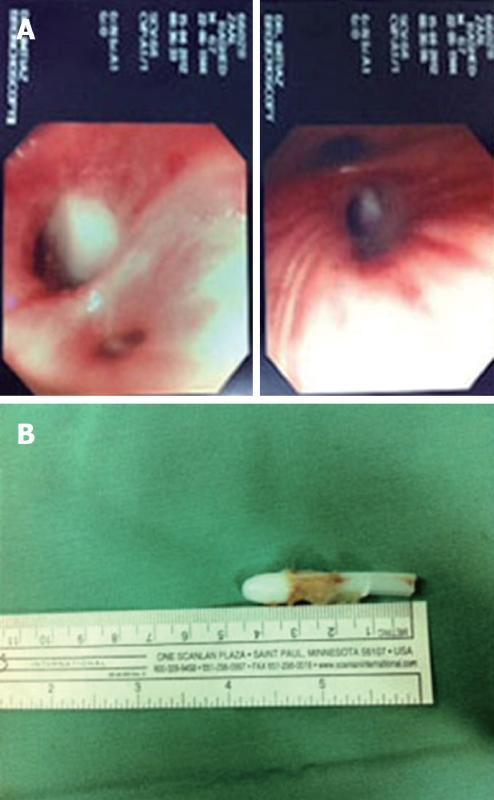

His computed tomography of the brain showed an old infarct and microangiopathic ischemic change. His respiratory rate was 35/minute, O2 saturation 88%-89% and blood pressure 90/50 mmHg. He was conscious and oriented but both his upper and lower limbs were spastic. Auscultation of the chest revealed decreased breath sounds on the right side. A subsequent X-ray of the chest did not show any foreign body (Figure 1). He was immediately taken to the operating room.

After putting on ECG leads, pulse oximeter, oxygen through a face mask and noninvasive blood pressure measurement, Xylocaine 2% was infiltrated into the trachea through the tracheostomy tube. About 1 mg of Midazolam was given intravenously and 15 mL/h propofol infusion was commenced.

The fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed a fractured part of the obturator deeply lodged in the right bronchus (Figure 2A). After suction of secretions, the obturator was removed with endoscopic forceps and it was pulled out from the tracheostomy tube with artery forceps (Figure 2B). After the uneventful procedure, the patient was sent to the recovery room. Two days later, the patient was referred back to the primary hospital for long term management.

The first case of a fractured, metallic tracheostomy tube was reported by Bassoe et al[2] in 1960. Since then, this kind of a complication has been published in the medical literature frequently, with all kinds of tracheostomy tubes (TT). The composition of TTs range from metal, poly vinyl chloride to silicone[3]. A number of factors predispose fracture of one of the flanges of the TT. The most frequent weak points of TT are the junctions between the tube and the neck plate, the distal end of the tube and the fenestration site[4,5]. In our case, it was not the TT but part of the obturator (introducer) which fractured and migrated to the distal trachea and was noticed during a routine change of tracheostomy tube by the staff.

Foreign body aspiration can be a life-threatening emergency. An aspirated solid or semisolid object may lodge in the larynx or trachea. If the object is large enough to cause nearly complete obstruction of the airway, asphyxia may rapidly lead to death[6].

Tracheobronchial foreign body (TFB) aspiration is rare in adults, although the incidence rate rises with advancing age. Risk factors for TFB aspiration in adults are a depressed mental status or impairment in the swallowing reflex[5]. Symptoms associated with TFB aspiration may range from cough, dyspnea, fever and acute asphyxiation with or without complete airway obstruction. In adults, many other medical conditions mimic breathing abnormalities similar to those associated with TFB aspiration. In our case, there was a definitive history of a missing part of the obturator during a change of the TT.

If the history is not suggestive, then only a high index of suspicion can ensure proper diagnosis and timely removal of the foreign body[6]. Initial treatment is airway management. Radiographic imaging may assist in localizing the foreign body. Bronchoscopic removal of the foreign body is necessary to avoid long-term sequelae. Flexible bronchoscopy is effective both in the diagnosis and removal of foreign bodies[7].

Almost all aspirated foreign bodies can be extracted bronchoscopically. If rigid or flexible bronchoscopy is unsuccessful, surgical bronchotomy or segmental resection may be necessary. Chronic bronchial obstruction with bronchiectasis and destruction of lung parenchyma may require segmental or lobar resection.

A pulmonologist or thoracic surgeon with experience in foreign body extraction should immediately perform bronchoscopic inspection and extraction of the object[8].

An anesthesiologist may be needed to maintain adequate ventilation and control of the upper airway during diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Rigid bronchoscopy is performed with the patient under general anesthesia or heavy sedation[8].

As foreign bodies in the TBT are uncommon in adults, the clinician must be vigilant regarding their possibility. Foreign body aspiration should be considered especially in the etiology of recurrent lung diseases and in the presence of risk factors for aspiration, in particular with different neurological and neuromuscular diseases. They can be safely and successfully removed in the majority of patients by using fiberoptic bronchoscopy under local anesthesia alone or under local anesthesia with sedation. An endotracheal intubation is recommended in cases of a repeated procedure.

An intermittent review of the techniques of tracheostomy care should be done, including timely check-ups for signs of wear and tear which can possibly eliminate such avoidable late complications[9].

Since there are no universally accepted and published standards of care for a tracheostomy tube, the policy should be to provide patients who require an indwelling tracheostomy tube with the following recommendations for home care: (1) Replace the tracheostomy tube every 6 mo; (2) Change/clean the inner cannula every 48 h; (3) Replace the tracheostomy ties weekly; (4) Change the dressing daily; and (5) Use nocturnal humidification[10].

In conclusion, cases of tracheostomy tube fractures and aspiration into TBT have been reported in the literature. We, hereby, report a rare case of the TT obturator that had fractured and migrated to the right main stem bronchus. Proper care and high vigilance when the obturator is removed during suction and cleaning of the TT is of high clinical importance.

P- Reviewer Feltracco P S- Editor Song XX L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Qureshi A, Behzadi A. Foreign-body aspiration in an adult. Can J Surg. 2008;51:E69-E70. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Bassoe HH, BOE J. Broken tracheotomy tube as a foreign body. Lancet. 1960;1:1006-1007. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Piromchai P, Lertchanaruengrit P, Vatanasapt P, Ratanaanekchai T, Thanaviratananich S. Fractured metallic tracheostomy tube in a child: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:234. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Majid AA. Fractured silver tracheostomy tube: a case report and literature review. Singapore Med J. 1989;30:602-604. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Alqudehy ZA, Alnufaily YK. Fractured tracheostomy tube in the tracheobronchial tree of a child: case report and literature review. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;39:E70-E73. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Boyd M, Chatterjee A, Chiles C, Chin R. Tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration in adults. South Med J. 2009;102:171-174. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Swanson KL, Prakash UBS, McDougall JC, Mithan DE, Edeu ES, Brutinel MW, Utz JP. Airway foreign bodies in adults. J Bronchol. 2003;10:107-111. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Warshawsky ME, Mosenifar Z. Foreign body aspiration. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/298940-overview. Updated: June 6, 2012. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | White AC, Kher S, O’Connor HH. When to change a tracheostomy tube. Respir Care. 2010;55:1069-1075. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Krempl GA, Otto RA. Fracture at fenestration of synthetic tracheostomy tube resulting in a tracheobronchial airway foreign body. South Med J. 1999;92:526-528. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |