Peer-review started: January 6, 2018

First decision: January 23, 2018

Revised: January 30, 2018

Accepted: February 28, 2018

Article in press: February 28, 2018

Published online: May 18, 2018

This case report describes in detail an erosive distal diaphyseal pseudotumor that occurred 6 years after a complex endoprosthetic hinge total knee arthroplasty (TKA). A female patient had conversion of a knee fusion to an endoprosthetic hinge TKA at the age of 62. At her scheduled 6-year follow-up, she presented with mild distal thigh pain and radiographs showing a 6-7 cm erosive lytic diaphyseal lesion that looked very suspicious for a neoplastic process. An en bloc resection of the distal femur and femoral endoprosthesis was performed. Histologic review showed the mass to be a pseudotumor with the wear debris emanating from within the femoral canal due to distal stem loosening. We deduce that mechanized stem abrasion created microscopic titanium alloy particles that escaped via a small diaphyseal crack and stimulated an inflammatory response resulting in a periosteal erosive pseudotumor. The main lesson of this report is that, in the face of a joint replacement surgery of the knee, pseudotumor formation is a more likely diagnosis than a neoplastic process when encountering an expanding bony mass. Thus, a biopsy prior to en bloc resection, would be our recommended course of action any time a suspicious mass is encountered close to a TKA.

Core tip: Pseudotumor formation is a biologic response to microscopic metal particulate debris observed in metal-to-metal total hip bearings. It is considered non-existent in total knee arthroplasty (TKA), where the bearing surface articulates metal-to-ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene. This report describes a rare case of pseudotumor formation in an endoprosthetic hinge TKA, as a result of femoral stem loosening with metallic debris exiting through a small crack in the distal femoral diaphysis. This case reveals that pseudotumor formation should always be considered when evaluating an expanding mass around a TKA.

- Citation: Chowdhry M, Dipane MV, McPherson EJ. Periosteal pseudotumor in complex total knee arthroplasty resembling a neoplastic process. World J Orthop 2018; 9(5): 72-77

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v9/i5/72.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v9.i5.72

All orthopaedic devices when implanted into the human body have the potential to cause immunologic reaction. Most reactions occur as a result of particulate debris formation stemming from mechanical implant loosening, breakage, interface corrosion/fretting or articular bearing wear. In total joint arthroplasty, the dominant inflammatory reaction encountered is osteolysis/synovitis reaction[1,2]. This inflammatory response is a result of high molecular weight polyethylene (HMWPE) and/or poly-methyl-meth-acrylate (PMMA) particles that activate a macrophage-predominant reaction that, in the end, causes bone resorption and elicits a significant articular and, on occasion, periarticular synovitis[3].

Another inflammatory reaction observed more recently in the last 2 decades is the pseudotumor phenomenon[4,5]. Its prevalence is almost exclusively associated with metal-to-metal articular total hip bearings[6]. The pseudotumor reaction is distinctly different than the classic HMWPE/PMMA induced osteolysis/synovitis reaction, as it is primarily a lymphocytic response to reactive metal debris. It is a non-neoplastic, sterile, solid and/or cystic lesion that frequently extends beyond the articular joint capsule[7]. Although macrophages are seen in the pseudotumor response, the primary cellular response is lymphocytic[8].

As one would expect, pseudotumor formation in TKA is very rare as there are no knee systems that articulate metal-to-metal. In this report we describe a large pseudotumor that presented as a distal femoral-diaphyseal periosteal soft tissue tumor 6 years after insertion of an endoprosthetic hinge TKA. We present histologic review of the pseudotumor and forensically deduce the origin of the metal debris that resulted in this inflammatory soft tissue response.

This unique case involves a 68-year-old female who was hit by a car as a pedestrian crossing the street and was dragged along for a distance. She was 35-year-old at the time of injury which resulted in an open right tibial fracture with severe soft tissue loss over the proximal one-third of the tibia. She had a total of 5 surgeries over 3 years to treat her fracture and overlying infection. A medial gastrocnemius flap was rotated to cover the medial knee and tibia. Her ultimate reconstruction was a knee fusion at age 38, which was stabilized with a cast rather than internal fixation. Her knee fusion surgery was successful. Since her fusion she has had no problems with infection.

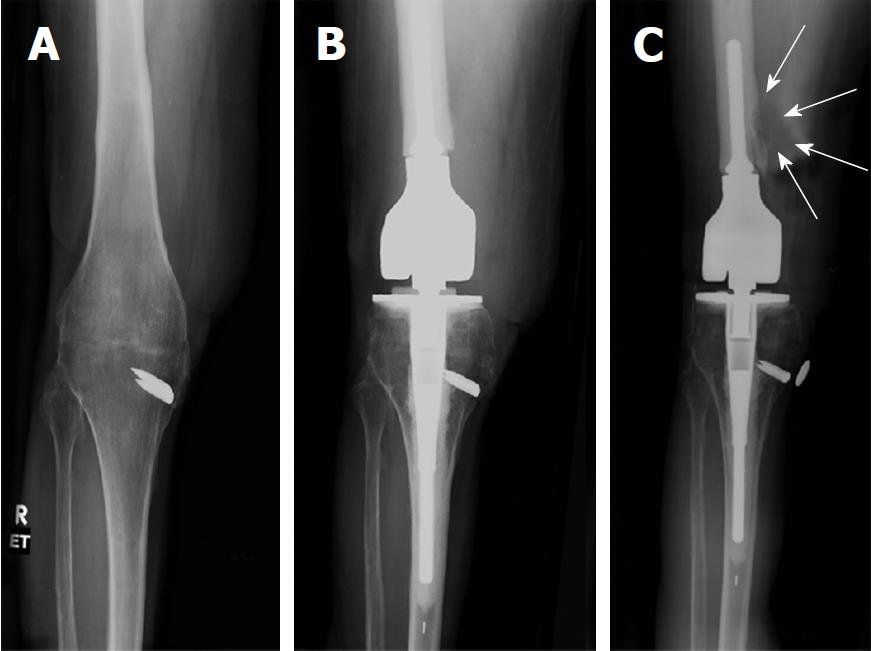

Twenty-four years later, at the age of 62, she presented to our clinic with severe pain in her back and ipsilateral hip. She wanted her knee fusion taken down and converted to a TKA. A careful pre-operative review indicated intact muscular firing of her quadriceps musculature. Clinically, she had an intact patellar tendon into the tibial tubercle. Studies evaluating for residual infection at the knee and tibia were negative. Her pre-operative radiograph of the knee fusion is shown in Figure 1A.

A salvage TKA was performed with segmental resection of her distal femur. She was reconstructed with a custom reduced-size endoprosthetic hinge device based upon the Orthopaedic Salvage System (OSS™) knee design (Zimmer-Biomet, Warsaw, IN, United States). Due to her soft tissue loss over the medial knee and tibia, the prosthetic joint line was placed cephalad. Her post-operative recovery was unremarkable. Her ultimate knee range of motion within the first year was 0-80 degrees. In addition, she had no knee extensor lag. Her reconstruction is shown in Figure 1B.

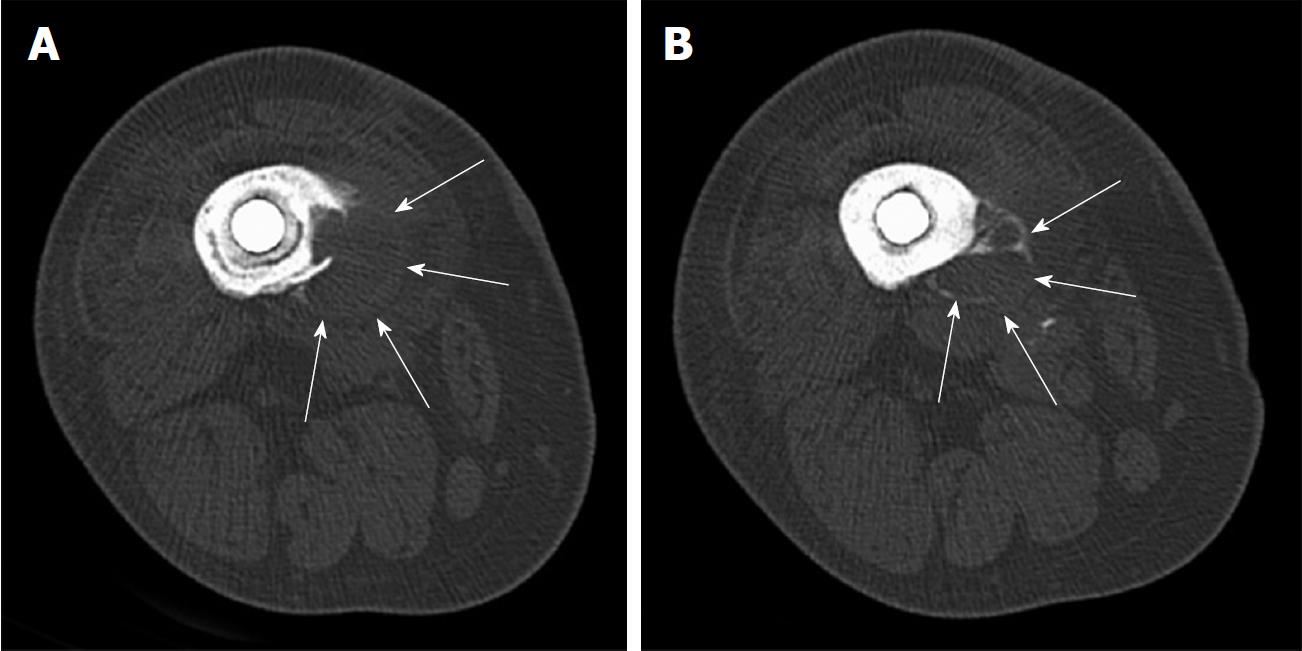

Six years post-operatively, at her scheduled follow-up, the patient described mild distal thigh and knee pain while walking. Her knee was cool on examination. Knee range of motion was 0-80 degrees of flexion with no extension lag and her knee felt stable. Radiographs showed concerning findings in the distal diaphysis (Figure 1C). There was a radiolucent line in the distal diaphyseal cement mantle, but more concerning was a periosteal erosion and surrounding soft tissue mass that resembled a possible neoplastic process. A CT scan of the distal femur revealed an eccentric lesion of the distal diaphysis of the femur that appeared to be emanating from the outer cortex of the medial diaphysis. The soft tissue mass was approximately 7 cm in length and 2-3 cm in breadth and was partly surrounded by a calcific border (Figure 2).

Her knee joint aspiration was negative for culture growth, including fungus and acid fast bacillus. The articular white blood cell count was 259 with 71% neutrophils. Alpha-defensin and Synovasure® (Zimmer-Biomet, Warsaw, IN, United States) tests were both negative. Her serum CRP and ESR levels were normal. Evaluation for metastatic disease was negative.

Our surgical plan was for en bloc removal of the femoral diaphysis, including the femoral stem. We chose not to biopsy the mass in order to avoid neoplastic contamination of the extended endoprosthetic joint space.

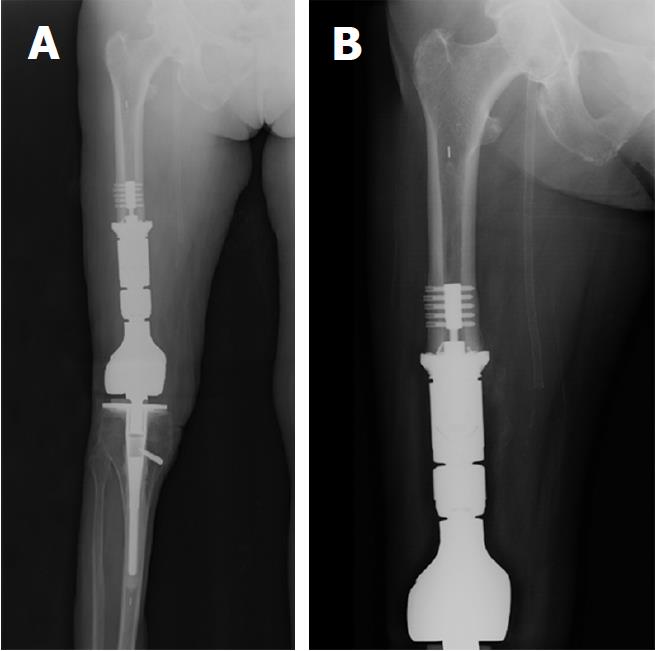

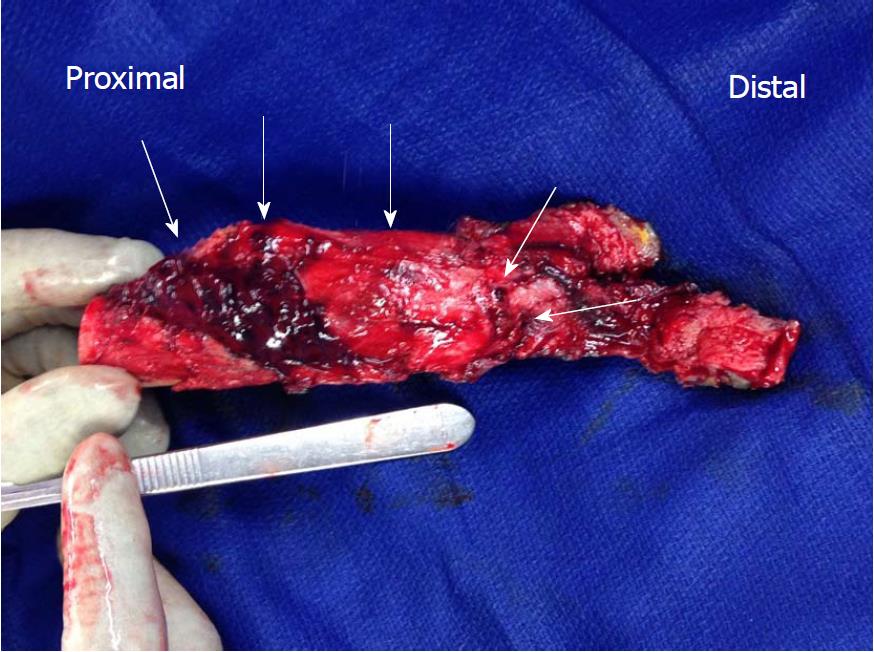

Post-operative radiographs of the revision surgery are shown in Figure 3. Nine centimeters of the femoral diaphysis was resected en bloc with the femoral stem, femoral diaphysis, and tumor mass. The femur was reconstructed with additional intercalary segments using the OSS Knee system. Fixation to the native femur was achieved with a femoral compress device (Zimmer-Biomet, Warsaw, IN, United States). Upon submission of the en bloc specimen to pathology, the tumor was cut open. We saw a multi-cystic, dark grey colored pseudotumor. The base of the pseudotumor emanated from the femoral diaphysis. We did not see any metallosis within the articular joint space (Figure 4).

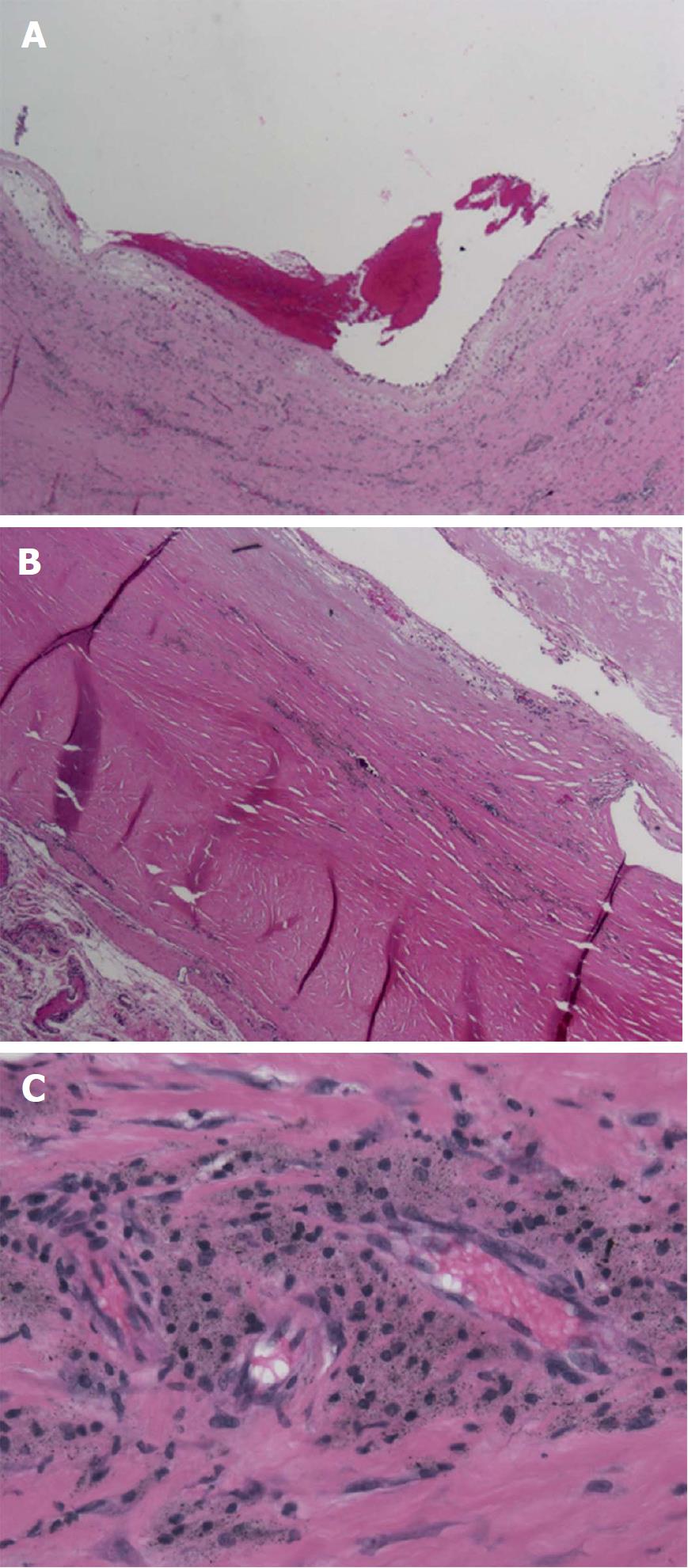

The microscopic examination (Figure 5) of the resected en bloc section revealed a partially solid and cystic lesion encased in a fibrous pseudo-capsule. There were numerous foreign body histiocytes containing waxy amorphous material. Perivascular lymphocytes and histiocytes were prominent. The specimen was formally diagnosed as a metallic debris pseudotumor. There was no evidence of any neoplastic process.

The patient's post-operative recovery was again uneventful. She had complete wound healing. Her range of motion at one-year follow-up was 0-88 degrees of flexion and there was no extensor lag.

Pseudotumor formation occurs as a result of metallic particulate debris eliciting a cell-mediated immune reaction that attempts to “encapsulate” the debris. Unfortunately, the pseudotumor sac does not limit its spread to the articular joint, which is unlike the HMWPE/PMMA osteolytic reaction. Pseudotumors generally spread along intermuscular planes[9]. In THA, pseudotumors are frequently found along the iliopsoas extending into the pelvis, in between the muscular planes of the thigh, and in between the muscular planes of the outer pelvis. Furthermore, pseudotumor masses can also protrude into the subcutaneous tissues when they herniate out from muscular planes.

We have searched the entire Medline database and to the best of our knowledge, have found only 5 case reports describing pseudotumors after a TKA[10-14]. We have reviewed all 5 articles carefully. Three of the articles describe an enlarged synovial sac around the total knee due to polyethylene wear debris and are not, in our opinion, “true” pseudotumors from metal wear debris[11,12,14]. One case does report a pseudotumor mass into the popliteal fossa. In this case, there was a broken polyethylene bearing and metal to metal contact of the femur onto the tibia creating metal debris. However, localized masses are known to frequently protrude posteriorly, especially with polyethylene debris. We feel this is not a classic metal-induced pseudotumor[13]. The fifth case, in our opinion, is most re–presentative of an encapsulated pseudotumor, but the wear debris originated from both polyethylene and metal debris[10].

Our case is unique for several reasons. First, this is the only report of a pseudotumor arising from a loose femoral stem despite a well-functioning TKA implant. Upon sectioning of the pseudotumor to its base, we observed a small black hole emanating from the outer diaphyseal cortex. This hole was actually an anterolateral crack in the distal femoral cortex which communicated into the medullary canal. The debris originated from mechanical abrasion of the femoral stem with adjacent cement and bone. Upon further inspection, we found the distal one-half of the femoral stem to be mechanically debonded from the cement mantle. We also noted broken/cracked cement in the distal one-fourth of the stem region. From microscopic review of the en bloc resection, we deduce that the pseudotumor emanated from within the femoral diaphysis and tracked outward to create an encapsulated mass outside of the femoral diaphysis. With a short, cemented femoral stem, repetitive cantilever bending forces caused the distal stem cement to fatigue, resulting in stem debonding. Subsequently, mechanized stem abrasion created microscopic titanium alloy particles. These particles then escaped via a small diaphyseal crack created by cantilever bend forces. The particles, seeking the path of least resistance, exited through the crack rather than the distal femur. The escaping particles then stimulated the inflammatory response that resulted in the localized pseudotumor. Since the process of titanium debris pumping outward was slow, we assume the encapsulated process was able to contain the exiting debris within the pseudotumor region. The reactive rind responded with an inflammatory response that, in radiographic review, looked like a neoplastic process.

Second, an erosive eccentric periosteal mass in the distal femoral diaphysis in a sexagenarian is rare. The radiographs show a soft tissue mass with peripheral calcification that mimics a periosteal osteosarcoma. The maximum incidence of osteosarcoma occurs in the age group 15-29[15]. In our case, although the patient did not fit the typical distributive curve of this tumor, we were still compelled by the radiographic findings to treat this as a neoplastic process. Osteosarcoma in the elderly patient can present as a primary, as well as a secondary, lesion. Secondary lesions occur from sarcomatous transformation in Paget’s disease or as a complication of irradiation. Since the patient did not have any of the above mentioned risk factors, our differential diagnosis involved a primary osteosarcoma. Osteosarcoma in the elderly has a poor prognosis if metastatic[16]. Our fear was that, with an existing endoprosthetic replacement within an extended joint space, a direct biopsy would have potentially contaminated the entire joint and caused the tumor to spread. We therefore chose not to biopsy the lesion and instead planned for a wide marginal excision. Fortunately, and much to our relief, the tumor was not neoplastic.

Our surgical approach took into consideration several factors. First, assuming the lesion was neoplastic, we wanted a wide marginal excision of the lesion to provide the least amount of local and systemic contamination of tumor cells. Second, this patient was highly satisfied with her endoprosthetic hinge TKA, so we strived to retain her knee function as best as possible. Therefore, our technique of resection was an extended arthrotomy from the knee joint line cephalad to a level just above the stem tip (measured from the end of the native femur). The procedure was performed with a pneumatic tourniquet for precise visualization.

The native femur was transected with a small sagittal saw above the stem tip. From this level and working distally to the knee joint, the intermuscular septum medially and laterally as well as the femur were elevated anteriorly from the posterior compartment along with the tumor mass via electrocautery. The hinge knee device was disconnected from the tibia and the entire segment of femur, femoral endoprosthetic construct, and tumor mass (lying upon the medial intermuscular septum) was delivered off the table for pathological examination. We were careful to avoid disrupting the tumor mass, so as not to contaminate the local joint area. To our surprise, upon cutting into the tumor, a gray pseudotumor mass was observed. This was also confirmed by microscopic frozen section review.

Our decision for a wide marginal excision, in retrospect, was overly aggressive, but we believed this decision to be the safest choice for the patient. Had we instead performed a standard arthrotomy, cut into the tumor, and found a neoplastic mass, we would have contaminated the entire knee region possibly resulting in an eventual high marginal above knee amputation or limb disarticulaton. Had we instead performed a radiographic-guided needle biopsy of the lesion, the diagnosis still may have been in doubt as a “negative” tissue biopsy could be considered a false negative result. We thought through the diagnostic process carefully and the option of a wide marginal excision was selected to provide the best definitive choice for diagnosis and treatment.

We find this case to be of further interest because almost all pseudotumors, whether in the hip, knee, or shoulder, usually present with a mass that extends into the soft tissues rather than confining itself to within the joint space. Pseudotumors of the hip tend to extend in between intermuscular planes[9], frequently following along the iliopsoas, gluteus muscles, and thigh muscles. In this case, the pseudotumor stayed within the joint space, which once again pointed in favour of a localised neoplastic lesion. We did not anticipate a pseudotumor presentation in this fashion.

Based on our experience, titanium debris differs from cobalt chrome alloy debris in that the former is dark grey whereas cobalt chrome debris is a light grey. Gross review of the opened pseudotumor showed it to be dark grey in nature. Furthermore, since the cobalt chrome femoral endoprosthesis was articulating with a high molecular weight polyethylene bearing, the chance of cobalt chrome debris formation was low. The knee joint was wearing well and the polyethylene bearing showed no significant wear damage to our gross observation. In our review of OSS endoprosthetic (7 cm) femurs cemented with 90 mm titanium alloy stems (n = 93), we have retrospectively found a loosening rate of 9.7%. We feel that a relatively short stem length (90 mm as opposed to 150 mm) paired with the 7 cm endoprosthetic femur is not long enough to resist the continued bending forces placed upon the femur with a hinge mechanism. We now routinely utilize the 150 mm cemented, bowed stem.

In summary, the lesson here is that pseudotumor reactions, unlike osteolytic reactions, form from reactive metallic debris. In the knee, the source of the metallic debris will always be mechanical loosening or catastrophic polyethylene wear-through with abnormal metal-on-metal contact. In the face of a recent joint replacement surgery of the knee, pseudotumor formation is a more likely diagnosis than a neoplastic process when an expanding mass is encountered. Thus, our experience with this case leads us to believe that an intra-operative biopsy of the lesion at the time of reconstruction, prior to en bloc resection of the femur, would be the recommended course of action.

A 68-year-old female, six years after a complex revision total knee arthroplasty (TKA) with an endoprosthetic hinge device, presents with distal thigh pain and an eccentric periosteal mass adjacent to the medial diaphyseal cortex.

The radiographic characteristics of the periosteal mass suggested a neoplastic process, but the histologic review of the lesion at the time of wide marginal excision showed the lesion to be a pseudotumor.

Preoperatively, based on radiographic review and CT scan of the lesion, we strongly suspected the mass to be a neoplasia; we did not suspect this lesion to be a pseudotumor.

As with any abnormal presentation involving a TKA, infection must always be ruled out first. Our laboratory tests included CBC with differential, ESR, and quantitative CRP. We also performed a knee aspiration, sending the fluid for cultures, Alpha-defensin, Synovasure® and cell count analysis.

For this case, we utilized mutliplanar radiographs and a CT scan of the femur and knee.

Visual review of the tumor showed the mass to be cystic with a dark grey inner complexion and a cavity filled with sero-sanguinous fluid. Histologic examination of the mass showed characteristic cells and structures consistent with a metal debris induced pseudotumor.

The tumor mass was thought to be neoplastic; therefore, we performed an en bloc removal of the distal native femur, femoral endoprosthetic construct, and tumor mass.

In the entire Medline literature, there are only 5 case reports describing a pseudotumor about a TKA; of these 5 reports, only one was, in our opinion, a true metal-induced pseudotumor.

Pseudotumor: a non-neoplastic, sterile, cystic lesion that develops as a result of an inflammatory reaction to small particulate metal debris.

In the face of a recent joint replacement surgery of the knee, pseudotumor formation is a more likely diagnosis than a neoplastic process when an expanding mass is encountered.

CARE Checklist (2013): The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2013), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2013).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopaedics

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Wu CC S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Cooper HJ, Ranawat AS, Potter HG, Foo LF, Koob TW, Ranawat CS. Early reactive synovitis and osteolysis after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:3278-3285. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Noordin S, Masri B. Periprosthetic osteolysis: genetics, mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions. Can J Surg. 2012;55:408-417. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bitar D, Parvizi J. Biological response to prosthetic debris. World J Orthop. 2015;6:172-189. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 141] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 111] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Frølich C, Hansen TB. Complications Related to Metal-on-Metal Articulation in Trapeziometacarpal Joint Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Funct Biomater. 2015;6:318-327. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sehatzadeh S, Kaulback K, Levin L. Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty: an analysis of safety and revision rates. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2012;12:1-63. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Bayley N, Khan H, Grosso P, Hupel T, Stevens D, Snider M, Schemitsch E, Kuzyk P. What are the predictors and prevalence of pseudotumor and elevated metal ions after large-diameter metal-on-metal THA? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:477-484. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Daniel J, Holland J, Quigley L, Sprague S, Bhandari M. Pseudotumors associated with total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:86-93. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Campbell P, Ebramzadeh E, Nelson S, Takamura K, De Smet K, Amstutz HC. Histological features of pseudotumor-like tissues from metal-on-metal hips. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2321-2327. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 365] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McPherson E, Dipane M, Sherif S. Massive pseudotumor in a 28mm ceramic-polyethylene revision THA: a case report. Reconstructive Review. 2014;4:11-17. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Benevenia J, Lee FY, Buechel F, Parsons JR. Pathologic supracondylar fracture due to osteolytic pseudotumor of knee following cementless total knee replacement. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;43:473-477. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kenan S, Kahn L, Haramati N, Kenan S. A rare case of pseudotumor formation associated with methyl methacrylate hypersensitivity in a patient following cemented total knee arthroplasty. Skeletal Radiol. 2016;45:1115-1122. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sivananthan S, Pirapat R, Goodman SB. A Rare Case of Pseudotumor Formation following Total Knee Arthroplasty. Malays Orthop J. 2015;9:44-46. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mavrogenis AF, Nomikos GN, Sakellariou VI, Karaliotas GI, Kontovazenitis P, Papagelopoulos PJ. Wear debris pseudotumor following total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:9304. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kinney MC, Kamath AF. Osteolytic pseudotumor after cemented total knee arthroplasty. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2013;42:512-514. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Stark A, Kreicbergs A, Nilsonne U, Silfverswärd C. The age of osteosarcoma patients is increasing. An epidemiological study of osteosarcoma in Sweden 1971 to 1984. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:89-93. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Jeon DG, Lee SY, Cho WH, Song WS, Park JH. Primary osteosarcoma in patients older than 40 years of age. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:715-718. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |