Published online Mar 15, 2016. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i3.314

Peer-review started: November 4, 2015

First decision: December 11, 2015

Revised: December 25, 2015

Accepted: January 16, 2016

Article in press: January 19, 2016

Published online: March 15, 2016

Processing time: 125 Days and 12.6 Hours

AIM: To estimate the incidence of esophageal cancer (EC) in Kilimanjaro in comparison to other regions in Tanzania.

METHODS: We also examined the clinical, epidemiologic, and geographic distribution of the 1332 EC patients diagnosed and/or treated at Ocean Road Cancer Institute (ORCI) during the period 2006-2013. Medical records were used to abstract patient information on age, sex, residence, smoking status, alcohol consumption, tumor site, histopathologic type of tumor, date and place of diagnosis, and type and date of treatment at ORCI. Regional variation of EC patients was investigated at the level of the 26 administrative regions of Tanzania. Total, age- and sex-specific incidence rates were calculated.

RESULTS: Male patients 55 years and older had higher incidence of EC than female and younger patients. Of histopathologically-confirmed cases, squamous-cell carcinoma represented 90.9% of histopathologic types of tumors. The administrative regions in the central and eastern parts of Tanzania had higher incidence rates than western regions, specifically administrative regions of Kilimanjaro, Dar es Salaam, and Tanga had the highest rates.

CONCLUSION: Further research should focus on investigating possible etiologic factors for EC in regions with high incidence in Tanzania.

Core tip: In the manuscript “Clinical and epidemiologic variations of esophageal cancer in Tanzania”, the authors describe the geographic distribution of esophageal cancer in Tanzania. The regions of Dar es Salaam and Kilimanjaro have higher incidences of esophageal cancer in comparison to other regions of Tanzania. There were also higher incidences found in the eastern and central parts of Tanzania compared to Western Tanzania. The authors did not find any differences in the age, sex, and histopathologic distribution of esophageal cancer when grouping the regions based on incidence rates.

- Citation: Gabel JV, Chamberlain RM, Ngoma T, Mwaiselage J, Schmid KK, Kahesa C, Soliman AS. Clinical and epidemiologic variations of esophageal cancer in Tanzania. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2016; 8(3): 314-320

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v8/i3/314.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v8.i3.314

Globally, esophageal cancer (EC) is the 8th most common incident cancer and the cancer with the 6th highest mortality[1,2]. There are two histologic types of EC that are commonly diagnosed, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adenocarcinoma (AC). SCC has been linked to tobacco and alcohol use while AC has been linked to diet and esophageal reflux; both are associated with older age[3-5]. The incidence of esophageal AC is often significantly higher in developed than developing countries while the incidence of SCC is usually higher in developing countries, including Africa, than developed countries[6,7]. In certain developed countries in East Asia, such as China and Japan, the incidence of SCC is much higher than AC incidence[8].

Approximately 80% of all EC occur in developing countries[2]. Africa specifically has a much higher incidence of EC in the Eastern and Southern regions[6]. The highest risk populations in Africa tend to be poorer, malnourished, and consume alcohol and tobacco[6,7,9,10]. There is also a large variation of risk for EC based on geographic region in Africa. Specifically, West Kenya and the Rift Valley Province of Kenya have shown high rates[6,11-15]. These regional differences may reflect risk and etiologic factors other than tobacco and alcohol[6,11].

Tanzania, located on the southern border of Kenya, is one of the poorest countries in the world, and a location where EC is commonly found[6]. Globocan estimates show an age-standardized rate of EC incidence in Tanzania for both sexes of 9.2 per 100000, which is the second highest cancer in Tanzania[16]. This rate is similarly high among other East African countries[16].

The Ocean Road Cancer Institute (ORCI), located in Dar es Salaam is the only specialized cancer treatment center in Tanzania, and the only facility in the country where radiation therapy is available[17]. The majority of EC patients in Tanzania are diagnosed at advanced disease stages (stage III and IV) and the main lines of treatment for such advanced stages include chemotherapy and radiation therapy[18]. It is also important to note that although AC and SCC develop from different cell types in the esophagus, they have similar treatment options[19]. Therefore, the majority of EC patients in Tanzania are treated at ORCI because of its radiation therapy facility[17].

Oncologists at ORCI have noted a higher number of EC patients referred from the Kilimanjaro region than other regions of Tanzania, despite similarities of population between regions, distance between the consultant hospital in the region and ORCI, and quality of roads between the consultant hospital and ORCI. This study aimed to estimate the incidence of EC in Kilimanjaro in comparison to other regions in Tanzania. The study also aimed to examine the demographic, clinical, and geographic distribution of EC patients in Tanzania during the period 2006-2013.

This study was conducted at ORCI, the only specialized cancer treatment center in Tanzania. The majority of EC patients treated at ORCI are referred from a few major hospitals in Tanzania after initial histopathologic confirmation or clinical diagnosis. ORCI keeps medical records for all patients treated by chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, including EC. These medical records and patient logbooks were utilized for this study, for the period 2006-2013. Logbooks were used as the original source for identifying medical record numbers of EC patients. Logbooks contain the names, medical record numbers, and type of cancer for each patient and were used to identify all patients with EC. Logbooks for 2007 were not available so manual search was performed to identify the EC medical records of 2007 without the initial list from the logbooks.

Abstracted information from the medical records included age, sex, residence, smoking status, alcohol consumption, tumor site, histopathologic type of tumor, treatment received, date and place of diagnosis, and date of beginning treatment at ORCI were abstracted from the medical records. This procedure was used for all EC patient records treated at ORCI during the period 2006-2013. There were a total of 1277 patient records collected and recorded. There were a total of 112 records of EC patients that were found in ORCI logbooks, but no medical record could be recovered (8.1%). Of the 1277 patients, 15 were removed because they were from a country other than Tanzania (n = 13) or had no recorded place of residence (n = 2), leaving a total of 1262 patients from ORCI records.

Surgical resection of EC is a major procedure that is mainly done at Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH) and the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC), and these hospitals are among the only in the country that provide histopathology diagnosis. Medical records for patients referred from MNH are included in the medical records of patients when they receive treatment at ORCI. For EC patients referred from KCMC, we created a list of their names and year of diagnosis and cross-referenced this information with all EC patients diagnosed and/or treated at KCMC during the period of 2006-2013. Additional information of patients from KCMC who were not included in the ORCI records were added to the final study dataset that included 1332 EC patients.

Regional variation in geographic distribution was investigated at the level of the 26 administrative regions of Tanzania. For calculating incidence rates, the total, age-, sex-specific population data of each region was obtained from the 2002 and 2012 Census of Tanzania[20,21]. The annual projected growth rate for each region was used to estimate the annual population for years 2006-2013[20,21].

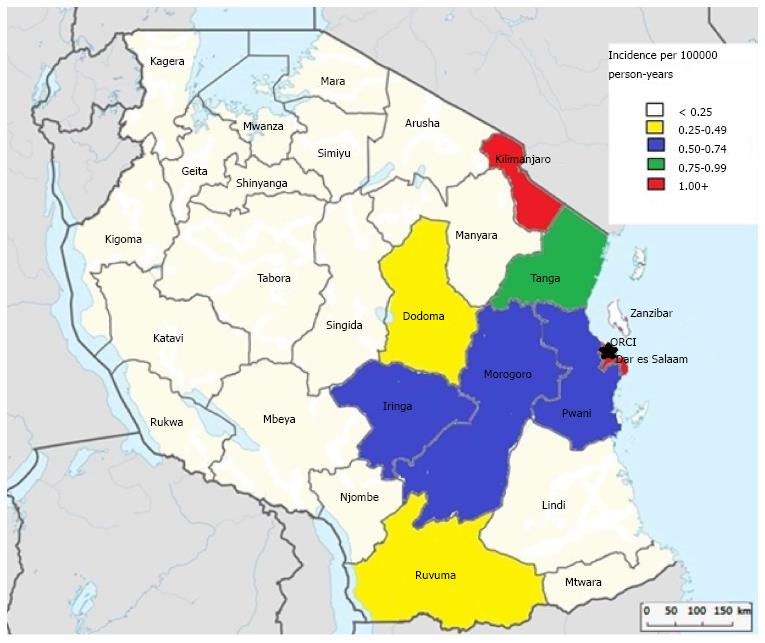

Based on the incidence rates that were calculated, the 26 administrative regions and Zanzibar were grouped into 5 groups. This was done to compare risk factors between different incidence groups. The very high incident group, with a rate of over 1.00 cases per 100000 person-years, was made up of the Dar es Salaam and Kilimanjaro regions. The high incident group, with an incidence of 0.75-0.99 cases per 100000 person-years was comprised of the region Tanga. The mid-range group ranged from 0.50-0.74 cases per 100000 person-years was made up of the administrative districts of Morogoro, Pwani, and Iringa. The regions of Ruvuma, and Dodoma represented the group with low incidence range, 0.25-0.49 cases per 100000 person-years. All other regions, Lindi, Mtwara, Njombe, Mbeya, Rukwa, Katavi, Tabora, Singida, Tabora, Kigoma, Manyara, Arusha, Mara, Simiyu, Kagera, Geita, Shinyanga, Zanzibar, and Mwanza, had an incidence of less than 0.25 cases per 100000 person-years and made up the very low incidence group. These groups will now be referred to as Group 1, Group 2, Group 3, Group 4, and Group 5, respectively.

Data were analyzed using χ2 tests to examine differences in the distribution of patient characteristics between the 5 incidence groups. These included differences based on demographic, clinical, and histopathologic variation of EC by age and sex groups and possible sex, age, and treatment differences among the two histologic types. The analysis for this paper was generated using SAS software, Version 9.3 of the SAS System. Copyright © 2011 SAS Institute Inc[22].

The study was approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center IRB and the ORCI Academic, Research, Publications and Ethics Committee.

Figure 1 categorizes all of the administrative regions in Tanzania based on the incidence rate per 100000 person-years. The administrative regions of Kilimanjaro and Dar es Salaam were found to have the highest incidence rates for EC in Tanzania for years 2006-2013, at 1.20 and 1.65 cases per 100000, respectively.

Table 1 illustrates the age, sex, year of treatment, histopathologic type, and smoking and alcohol history of the study population. Male patients comprised slightly over 2/3 of the study population (68%) and over half (60%) of the EC patients were aged 55 years and older. Over 50% of the EC patients smoked tobacco or consumed alcohol, however this rate may be much higher as over 20% had unknown alcohol and tobacco status. Over 90% of histopathologically-confirmed EC cases were SCC (Table 1).

| n (%) | |

| Age group (n = 1329) | |

| 15-34 yr | 78 (5.9) |

| 35-44 yr | 141 (10.6) |

| 45-54 yr | 246 (18.5) |

| 55-64 yr | 374 (28.1) |

| 65+ yr | 489 (36.8) |

| Sex (n = 1332) | |

| Male | 906 (68.0) |

| Female | 426 (32.0) |

| Year starting treatment at Ocean Road Cancer Institute (n = 1332) | |

| 2006 | 135 (10.1) |

| 2007 | 140 (10.5) |

| 2008 | 174 (13.1) |

| 2009 | 202 (15.2) |

| 2010 | 211 (15.8) |

| 2011 | 171 (12.8) |

| 2012 | 139 (10.4) |

| 2013 | 160 (12.0) |

| Histopathologic diagnosis (n = 626) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 569 (90.9) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 57 (9.1) |

| Smoking and alcohol history (n = 1332) | |

| Status | |

| Alcohol and smoking | 396 (29.7) |

| Alcohol only | 150 (11.3) |

| Smoking only | 137 (10.3) |

| Neither alcohol nor smoking | 371 (27.9) |

| Unknown | 278 (20.9) |

Table 2 displays the sex, age, and treatment distribution of both histopathologic types. The distribution of age group, sex, and treatment was not significantly different among SCC and AC patients. Males comprised nearly 2/3 of both SCC (67.1%) and AC (64.9%) patients. Sex distribution was not significantly different among SCC and AC patients (P = 0.73). Patients aged 55 and older were the majority of both SCC (63.2%) and AC (75.4%) patients. The distribution of age groups did not differ significantly between SCC and AC patients (P = 0.1702). The treatment received among SCC and AC patients also was not significantly different (P = 0.13).

| Squamous cell carcinoma (n = 569) | Adenocarcinoma (n = 57) | P value | |

| Sex | 0.7338 | ||

| Male | 382 (67.1) | 37 (64.9) | |

| Female | 187 (32.9) | 20 (35.1) | |

| Age group | 0.1702 | ||

| 15-34 yr | 34 (6.0) | 4 (7.0) | |

| 35-44 yr | 64 (11.2) | 1 (1.8) | |

| 45-54 yr | 111 (19.5) | 9 (15.8) | |

| 55-65 yr | 139 (24.4) | 15 (26.3) | |

| 65+ yr | 221 (38.8) | 28 (49.1) | |

| Treatment | 0.1349 | ||

| Radiation | 170 (29.9) | 16 (28.1) | |

| Chemotherapy | 13 (2.3) | 4 (7.0) | |

| Both | 263 (46.2) | 22 (38.6) | |

| None | 123 (21.6) | 15 (26.3) |

Table 3 illustrates the distribution of histopathologic type, sex, and age group among the different incident groups. Males comprised the majority of patients in every incident group (64.7%-73.6%). The distribution of sex was not significantly different among the different incident groups (P = 0.12). SCC was the majority histopathologic type among all groups (86.6%-98.2%). The histopathologic type composition did not differ significantly among incident groups (P = 0.13). Those aged 55 and older comprised over half of all incident groups (52.3%-70.5%). The age group distribution among the incident groups was not significantly different (P = 0.14).

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | P value | |

| Histology | 0.1269 | |||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 276 (92.0) | 54 (98.2) | 90 (89.1) | 39 (90.7) | 110 (86.6) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 24 (8.0) | 1 (1.8) | 11 (10.9) | 4 (9.3) | 17 (13.4) | |

| Sex | 0.1233 | |||||

| Males | 425 (65.6) | 75 (64.7) | 159 (73.6) | 71 (66.4) | 176 (71.8) | |

| Females | 223 (34.4) | 41 (35.3) | 57 (26.4) | 36 (33.6) | 69 (28.2) | |

| Age group | 0.1441 | |||||

| 15-34 yr | 41 (6.3) | 6 (5.2) | 13 (6.0) | 5 (4.7) | 14 (5.7) | |

| 35-44 yr | 65 (10.0) | 12 (10.4) | 28 (13.0) | 13 (12.1) | 23 (9.4) | |

| 45-54 yr | 110 (17.0) | 16 (13.9) | 46 (21.3) | 33 (30.8) | 41 (16.8) | |

| 55-64 yr | 196 (30.3) | 34 (29.6) | 57 (26.4) | 20 (18.7) | 67 (27.5) | |

| 65+ yr | 235 (36.3) | 47 (40.9) | 72 (33.3) | 36 (33.6) | 99 (40.6) |

In this study, the eastern and central parts of Tanzania had higher incidence rates compared to western parts of the country. This can be observed for all age groups and sexes. This is an interesting observation, as the Western part of Kenya has been noted to have a higher incidence compared to other areas in Kenya[6,10-14]. Because our study hospital (ORCI) is on the eastern side of Tanzania, the higher rates of the disease from eastern Tanzania might be related to more accessibility to care. It is worth noting that some regions with the lowest incidence rates are not a significantly farther distance than some of the regions with a higher incidence. For example, Manyara, a region in the lowest incidence group, is not significantly farther from ORCI than Kilimanjaro, a region in the highest incidence group.

Males had a higher incidence in all administrative regions, and in total comprised 68% of the EC patients included in this study. The male-to-female ratio reported in this study is consistent with other studies on EC from developed and developing countries[3,23,24].

SCC represented over 88% of all histopathologically -confirmed patients in every age and sex group. SCC also made up the majority of confirmed patients who received treatment. This finding is not surprising, as SCC has been noted to be the more prominent histopathologic type in developing countries[6,7,23]. The proportion of SCC and AC did not change significantly among administrative regions when grouped by incidence.

In this study, patients 55 years and older constituted over 64% of all EC patients in the study population. Older age was also found to be a risk factor for EC in a variety of studies from developing and developed countries[3,23,24]. The age distribution of patients did not change significantly among administrative regions when grouped by incidence.

The etiology of EC is important when considering factors that may contribute to a higher incidence in different regions of Tanzania. Some known risk factors for EC include age, sex, tobacco smoking, alcohol intake, obesity, and reflux[3-5]. No significant differences between regions with respect to age and sex exist. There is no available information detailing possible regional differences in lifestyle factors related to EC such as tobacco smoking, alcohol intake, viral infections, or customs.

It is worth noting that over 20% of SCC and AC patients who identified from the medical records, had no treatment information recorded. Lack of availability of treatment information in the medical records could be due to death of patients before starting treatment or seeking alternative medicine outside ORCI.

This study has several strengths. First, the large number of cases and several years of study population were assets for this study. Second, availability of reliable census data for Tanzania allowed us to calculate the incidence rates. Third, the limited number of treatment facilities in Tanzania also contributed to capturing most patients that had EC in Tanzania, who are usually diagnosed at advanced disease stages. Fourth, the availability of clinical information within ORCI and MNH records also contributed to our ability to accurately abstract information and cross-reference patients between the two hospitals.

The study also has a few limitations. While we included all the patients who were seen at ORCI for treatment, it is still a possibility that some patients might have died before reaching ORCI, and therefore contributed to possible underestimation of the incidence. There may also be additional missing cases due to difficultly in journey because of roads, climate, and terrain, patients not believing that treatments in the hospital can treat cancer, or because traveling to the hospital is too expensive. It is also possible that certain geographic areas of Tanzania experience these barriers to treatment and other lifestyle factors related to EC more strongly than others leading to a greater underestimation in those areas, however this information is not available and is a limitation of the study. Patients wishing to escape enumeration due to the large amount of people seeking treatment at ORCI also have the potential to seek treatment outside of Tanzania and contribute to possible underestimation of the incidence; however, this is unlikely because these patients would no longer receive the free universal medical care that is provided to citizens of Tanzania. Cross-referencing KCMC helped identifying patients not included in the ORCI records. However, this opportunity of utilizing the large hospital of KCMC with histopathologic resources was not available at small hospitals in Tanzania. The country has the goal of establishing more cancer centers in the future to avoid patients missing treatment. Finally, missing data was another limitation for this study[25,26]. HIV status is not commonly recorded for EC patients in Tanzania, as they receive the same treatment regardless of HIV condition. Other studies have reported that HIV is a risk factor for EC[27,28]. The missing data for tobacco smoking, alcohol intake, non-HIV viral infections, and other lifestyle factors, which are risk factors for EC, was also a limitation of this study[3-5].

This study confirmed the clinical impressions of physicians at ORCI of a higher proportion of EC patients from the Kilimanjaro region. The study also revealed higher incidence in patients from the Central and Eastern regions compared to Western Tanzania. This study confirmed previous findings about higher rates among older patients, higher male-to-female ratio, and higher SCC compared to AC on EC in East Africa[4,5].

Future studies should further address the difference in geographic distribution of EC in Tanzania. The studies should examine the etiological factors that may contribute to the higher incidence in Kilimanjaro and the Central and Eastern regions. Also, future studies should examine the possibility of underestimation of EC in Tanzania.

Esophageal cancers (ECs) are a top ten cancer both for incidence and mortality, globally. ECs are very common in developing countries. Previous studies have observed high rates of EC in western Kenya and in the Rift Valley. Oncologists at the Ocean Road Cancer Institute in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania noted what they believed to be a large number of patients being referred from the Kilimanjaro region in Tanzania for EC compared to other regions. Because of this, medical records were used to determine the geographic distribution of EC in Tanzania for 2013-2006.

This study brings to light the possibility of geographic differences in EC in Tanzania. This could lead to additional investigations to determine what etiologic factors may contribute to these differences. Additionally, the possibility of underestimation of EC in Tanzania should be further explored.

This is the first study to our knowledge to look at the distribution of EC in Tanzania. This study found that the regions of Dar es Salaam and Kilimanjaro had the highest incidences of EC in Tanzania. There were also generally higher incidences in the Eastern and Central parts of Tanzania compared to Western Tanzania.

This study brings to light differences in geographic distribution and potential access to care and underestimation of cancer patients in Tanzania.

The histology of the cancer is determined in a laboratory and is based on which cell type the cancer derives from.

Peer-reviewers noted that the incidence of EC in Tanzania was estimated in this study and clinical, epidemiologic, and geographic distribution from medical record information was described. Previous findings on EC were confirmed in this study and a difference in geographic distribution was revealed. There is potential for underestimation of EC in this study and the information is limited to Tanzania.

P- Reviewer: Mullin JM, Muguruma N, Natsugoe S S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Stewart BW, Wild CP, editors . World Cancer Report 2014. Lyon Cedex, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer 2014; . |

| 2. | Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74-108. [PubMed] |

| 3. | American Cancer Society. Esophageal Cancer. Available from: http: //www.cancer.org/cancer/esophaguscancer/detailedguide/esophagus-cancer-risk-factors. |

| 4. | Tettey M, Edwin F, Aniteye E, Sereboe L, Tamatey M, Ofosu-Appiah E, Adzamli I. The changing epidemiology of esophageal cancer in sub-Saharan Africa - the case of Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13:6. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Wolf LL, Ibrahim R, Miao C, Muyco A, Hosseinipour MC, Shores C. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy in a public referral hospital in Lilongwe, Malawi: spectrum of disease and associated risk factors. World J Surg. 2012;36:1074-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Parkin DM, Ferlay J, Hamdi-Cherif M, Sitas F. Cancer in Africa: Epidemiology and Prevention. USA: IARC Scientific Publication 2003; . |

| 7. | Zhang Y. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5598-5606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 736] [Cited by in RCA: 747] [Article Influence: 62.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 8. | Lin Y, Totsuka Y, He Y, Kikuchi S, Qiao Y, Ueda J, Wei W, Inoue M, Tanaka H. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in Japan and China. J Epidemiol. 2013;23:233-242. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Abnet CC, Corley DA, Freedman ND, Kamangar F. Diet and upper gastrointestinal malignancies. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1234-1243.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McGlashan ND. Oesophageal cancer and alcoholic spirits in central Africa. Gut. 1969;10:643-650. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Dawsey SP, Tonui S, Parker RK, Fitzwater JW, Dawsey SM, White RE, Abnet CC. Esophageal cancer in young people: a case series of 109 cases and review of the literature. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | White RE, Abnet CC, Mungatana CK, Dawsey SM. Oesophageal cancer: a common malignancy in young people of Bomet District, Kenya. Lancet. 2002;360:462-463. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ahmed N, Cook P. The incidence of cancer of the oesophagus in West Kenya. Br J Cancer. 1969;23:302-312. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Patel K, Wakhisi J, Mining S, Mwangi A, Patel R. Esophageal Cancer, the Topmost Cancer at MTRH in the Rift Valley, Kenya, and Its Potential Risk Factors. ISRN Oncol. 2013;2013:503249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wakhisi J, Patel K, Buziba N, Rotich J. Esophageal cancer in north rift valley of Western Kenya. Afr Health Sci. 2005;5:157-163. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Available from: http: //globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/Map.aspx. |

| 17. | African Cancer Registry Network (AFCRN). Tanzania Cancer Registry. Available from: http: //afcrn.org/membership/membership-list/114-tanzania. |

| 18. | National Cancer Institute. Esophageal Cancer Treatment. Available from: http: //www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/esophageal/Patient/page5. |

| 19. | Stanford Health Care. Information about Esophageal Cancer. Available from: http: //cancer.stanford.edu/gastrocolo/esophageal.html.. |

| 20. | National Bureau of Statistics. Tanzania in Figures 2012. Available from: http://www.tanzania-gov.de/images/downloads/tanzania_in_figures-NBS-2012.pdf. |

| 21. | National Bureau of Statistics. Tanzania Census 2002 Analytical Report. Available from: http://www.nbs.go.tz/tnada/index.php/catalog/7/download/12. |

| 22. | SAS Institute Inc. SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. Product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS. Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute Inc 2011; . |

| 23. | Available from: http: //www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/oesophagus/incidence/. |

| 24. | Available from: http: //www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/esophageal/HealthProfessional. |

| 25. | McHembe MD, Rambau PF, Chalya PL, Jaka H, Koy M, Mahalu W. Endoscopic and clinicopathological patterns of esophageal cancer in Tanzania: experiences from two tertiary health institutions. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Adeyi OA. Pathology services in developing countries-the West African experience. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:183-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kayamba V, Bateman AC, Asombang AW, Shibemba A, Zyambo K, Banda T, Soko R, Kelly P. HIV infection and domestic smoke exposure, but not human papillomavirus, are risk factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Zambia: a case-control study. Cancer Med. 2015;4:588-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dar NA, Islami F, Bhat GA, Shah IA, Makhdoomi MA, Iqbal B, Rafiq R, Lone MM, Abnet CC, Boffetta P. Poor oral hygiene and risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Kashmir. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1367-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |