Published online Feb 15, 2011. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v3.i2.19

Revised: January 31, 2011

Accepted: February 7, 2011

Published online: February 15, 2011

Intestinal lymphangiectasia in the adult may be characterized as a disorder with dilated intestinal lacteals causing loss of lymph into the lumen of the small intestine and resultant hypoproteinemia, hypogammaglobulinemia, hypoalbuminemia and reduced number of circulating lymphocytes or lymphopenia. Most often, intestinal lymphangiectasia has been recorded in children, often in neonates, usually with other congenital abnormalities but initial definition in adults including the elderly has become increasingly more common. Shared clinical features with the pediatric population such as bilateral lower limb edema, sometimes with lymphedema, pleural effusion and chylous ascites may occur but these reflect the severe end of the clinical spectrum. In some, diarrhea occurs with steatorrhea along with increased fecal loss of protein, reflected in increased fecal alpha-1-antitrypsin levels, while others may present with iron deficiency anemia, sometimes associated with occult small intestinal bleeding. Most lymphangiectasia in adults detected in recent years, however, appears to have few or no clinical features of malabsorption. Diagnosis remains dependent on endoscopic changes confirmed by small bowel biopsy showing histological evidence of intestinal lymphangiectasia. In some, video capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy have revealed more extensive changes along the length of the small intestine. A critical diagnostic element in adults with lymphangiectasia is the exclusion of entities (e.g. malignancies including lymphoma) that might lead to obstruction of the lymphatic system and “secondary” changes in the small bowel biopsy. In addition, occult infectious (e.g. Whipple’s disease from Tropheryma whipplei) or inflammatory disorders (e.g. Crohn’s disease) may also present with profound changes in intestinal permeability and protein-losing enteropathy that also require exclusion. Conversely, rare B-cell type lymphomas have also been described even decades following initial diagnosis of intestinal lymphangiectasia. Treatment has been historically defined to include a low fat diet with medium-chain triglyceride supplementation that leads to portal venous rather than lacteal uptake. A number of other pharmacological measures have been reported or proposed but these are largely anecdotal. Finally, rare reports of localized surgical resection of involved areas of small intestine have been described but follow-up in these cases is often limited.

- Citation: Freeman HJ, Nimmo M. Intestinal lymphangiectasia in adults. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2011; 3(2): 19-23

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v3/i2/19.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v3.i2.19

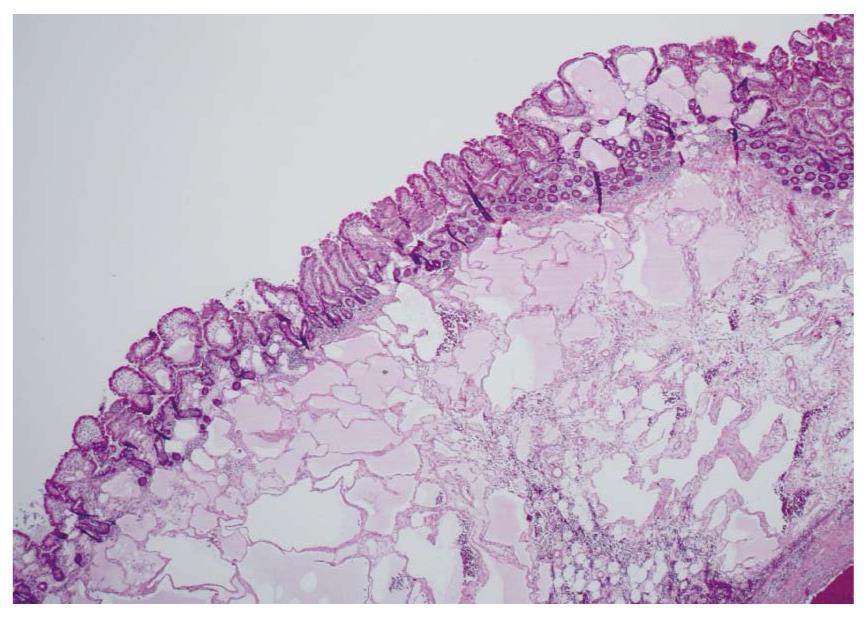

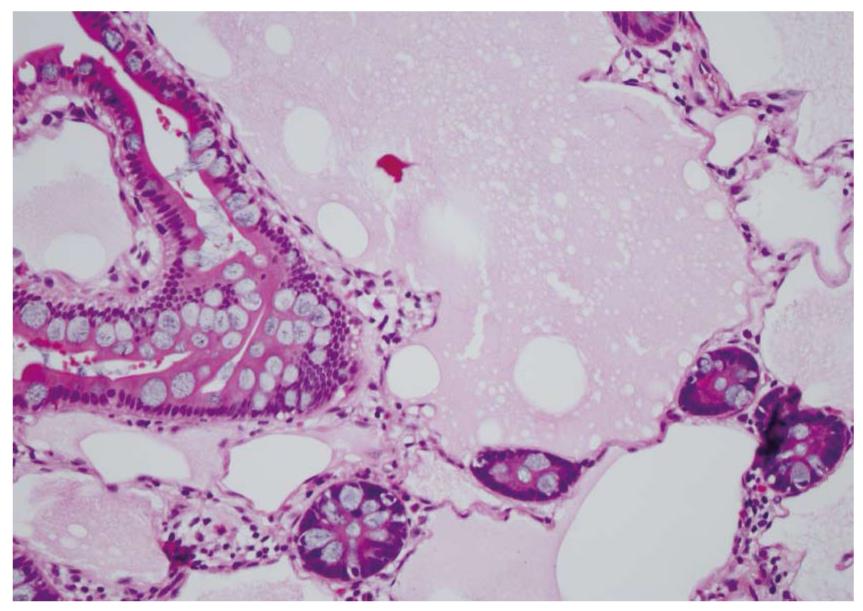

Waldman et al[1] first detailed cases of intestinal lymphangiectasia almost 50 years ago. In their cases, edema and hypoproteinemia were present with both hypoalbuminemia and hypogammaglobulinemia. Estimated measurements of the total body albumin pool using a radio-labeled albumin method were reduced while fecal excretion was increased. In some, steatorrhea was also present. Biopsies of the small bowel are needed to confirm the diagnosis[2]. These show prominent dilated lymphatics in the lamina propria region of the villous structure, often with extension into submucosa (Figures 1 and 2). Others have commented that these changes may be difficult to detect since dilation of intestinal lacteals or lymph containing capillaries may be quite focal[3]. Familial presentations were also recorded[1]. Most often affected were children and young adults, although even historically, diagnosis was initially also occasionally defined in older, even elderly, adults. The precise cause of intestinal lymphangiectasia with enteric protein loss remains obscure but changes in regulatory molecules involved in lymphangiogenesis have been reported in the duodenal mucosa[4].

Commonly reported clinical findings have traditionally described pitting edema, usually in a symmetrical distribution involving the lower limbs. If severe edema is evident, facial and scrotal (or vaginal) involvement may occur. Effusions may also develop in pleural, pericardial and peritoneal cavities with gross chylous ascites. Sonographic evidence of fetal ascites has also been reported[5]. Rarely, lymphedema (that may be difficult to differentiate from edema due to hypoalbuminemia and low oncotic pressure) and the so-called “Stemmer’s sign” (i.e. skin fibrosis on dorsum of the second toe due to chronic lymphedema)[6] have been described. It should be emphasized, however, that many of these clinical features likely reflect the severe end of the spectrum of clinical changes, especially in adults with intestinal lymphangiectasia. In recent years, directly due to the emergence of newer endoscopic methods, particularly video capsule endoscopy in adults, detection of mucosal changes suggestive of lymphangiectasia seem to be relatively common. For example, in a recent evaluation of 1866 consecutive endoscopic examinations, histological confirmation of duodenal lymphangiectasia was evident in 1.9%[7]. More significant, even if lymphangiectasia persisted on consecutive endoscopic studies over a year apart, there was no clinical evidence of malabsorption[7]. Therefore, it would seem that in most histologically-confirmed intestinal lymphangiectasia, clinical features may be very limited and the classical “textbook” recorded changes may be more reflective of the most severe end of the clinicopathological spectrum in adults.

In some, an abdominal mass may be noted[8], either on clinical evaluation or with radiological imaging studies, particularly ultrasound (with or without endoscopy) or computerized tomography. These masses are usually cystic and often represent associated lymphangiomas. The latter are entirely benign lesions that may be associated with lymphangiectasia in either small or large bowel[9,10]. The most commonly reported intestinal site is the duodenum[11], in part, perhaps, because these have been easier to detect with endoscopic evaluation showing a smooth, soft, polypoid cystic lesion with a broad base[10]. In others, a segmental area of edema and wall thickening may occur causing a localized obstruction and, occasionally, resulting in a segmental intestinal resection[12]. To some degree, evolving imaging methods not available during the era of the initial description of this disorder have enhanced our appreciation for these more extensive lymphatic changes.

A rare association of intestinal lymphangiectasia with celiac disease has been noted[13]; however, in most with primary intestinal lymphangiectasia, the intestinal mucosa appears to be otherwise normal on routine microscopic evaluation apart from the dilated lacteals. In addition, iron deficiency may occur[14] but it is not clear if there is any impairment of iron absorption in primary intestinal lymphangiectasia even if it primarily localized in the duodenum. Chronic occult blood loss may occur in some[15] and non-specific small bowel ulceration has been noted[14]. Rarely, massive bleeding has been recorded[16,17]. In a recent study using capsule endoscopy[18], an intriguing but statistically significant association with coincident small bowel angiodysplasia was noted, suggesting another possible mechanism for occult blood loss with lymphangiectasia. Recurrent hemolysis with uremia may occur[19] and, possibly, urinary iron loss from ongoing intravascular hemolysis may result. The mechanisms involved for malabsorption of fat and fat soluble vitamins are not fully defined and need to be further explored. However, osteomalacia associated with vitamin D deficiency has been noted[20] and tetany attributed to hypocalcemia has been reported[21].

Rarely, yellow nails have been described (i.e. “yellow nail syndrome”) in primary intestinal lymphangiectasia with dystrophic ridging and loss of the nail lunula. In addition, lymphedema and pleural effusions were noted[22]. Finally, an intriguing association with autoimmune polyglandular disease type 1 has been described[23,24].

Diagnosis is defined by endoscopic evaluation and biopsy of duodenum and/or jejunum[1,2] or alternatively from surgically resected small intestine. Dilated lacteals are detected in the mucosa, sometimes extending into the submucosa (Figures 1 and 2). Usually, the overlying small intestinal epithelium is completely normal. Sometimes, ileal biopsies from ileocolonoscopy may show the small intestinal histopathological changes. High-resolution magnifying video endoscopy may have an important role in detection of intestinal lymphangiectasia[25]. Video capsule studies may permit evaluation of the extent of the lymphangiectasia including the “yellow nail syndrome” and has been confirmed with surgical exploration[27-29]. Double-balloon enteroscopy has also emerged in the evaluation of malabsorption and up to 13% of patients were found to have yellow and white submucosal plaques, likely to be lymphangiectasis[30,31]. Although radiotracers and direct lymphatic imaging were often historically used, magnetic resonance imaging has also been applied in patients with intestinal lymphangiectasia to evaluate intestinal, mesenteric and thoracic duct changes[32].

Associated immunological changes have been described in a number of studies[33-36]. These findings include hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia and hypogammaglobulinemia. Lymphocytopenia occurs with B-cell depletion reflected by diminished immunoglobulins IgG, IgA and IgM, as well as T-cell depletion, especially in the number of CD4+ T-cells as naïve CD45RA+ lymphocytes. In addition, functional changes occur including impaired antibody responses and prolonged skin allograft rejection may result. Finally, a recent report indicates that T-cell thymic production failed to compensate for enteric T-lymphocyte loss suggesting multiple mechanisms are involved in lymphopenia associated with lymphangiectasia[37].

Enteric protein loss may be suspected if fecal alpha-1-antitrypsin is increased. Radio-labeled albumin studies may demonstrate increased loss but prolonged scanning may be required as protein loss may be periodic or intermittent. In some cases, localization of the site of protein loss may also be possible[38]. Imaging with ultrasound or computerized tomography may define intestinal wall thickening, mesenteric “edema” or ascites[39-41]. Magnetic resonance imaging has also been reported for use in the diagnosis of protein losing enteropathy[42]. Lymphoscintigraphy may also be used to anatomically define the lymphatic system but this procedure has largely become historical, less often performed and may correlate poorly with the severity of protein loss[43].

It is especially critical to ensure that changes of intestinal lymphangiectasia are not secondary to some other cause, particularly from a “downstream” obstruction, including another intestinal disease (e.g. Crohn’s disease, Whipple’s disease from Tropheryma whipplei infection[44], intestinal tuberculosis), radiation- and/or chemotherapy-induced retroperitoneal fibrosis, or even a circulatory cause (e.g. constrictive pericarditis). Many gastric disorders (e.g. Mentrier’s disease) or inflammatory disorders involving the intestine (e.g. protein losing enteropathy in systemic lupus erythematosus) may also cause protein loss without intestinal lymphangiectasia[45]. Finally and particularly significant are malignant lymphomas that may secondarily cause lymphatic obstruction and intestinal lymphangiectasia with intestinal protein loss. In these, resolution of the protein-losing enteropathy with the intestinal lymphangiectasia may result from lymphoma treatment[46-48]. Conversely, it also conceivable that lymphoma may complicate the clinical course of long-standing intestinal lymphangiectasia per se. Both intestinal and extra-intestinal lymphomas have been described, usually B-cell type, during the course of long-standing intestinal lymphangiectasia[49]. A definite mechanism has not been defined although depressed immune surveillance may result from ongoing and persistent depletion of immunoglobulins and lymphocytes.

Treatment has traditionally included a low fat diet along with a medium-chain triglyceride oral supplement[50]. The latter directly enters the portal venous system and bypasses the intestinal lacteal system. Some believe that reduced dietary fat prevents lacteal dilation and possible rupture with loss of protein and lymphocyte depletion. In some, this therapy can cause reversal of clinical and biochemical changes, being more effective in children than adults[51]. In some that fail to respond, other forms of nutritional support have been required[52].

Other therapies have been reported. Tranexamic acid, an antiplasmin, has been used to normalize immunoglobulin and lymphocyte numbers[53]. Octreotide was reported to be useful but the mechanism is not clear[54]. Segmental small bowel resection for localized areas of lymphangiectasia has been recorded[55]. Steroids remain controversial although effectiveness in systemic lupus erythematosus with protein-losing enteropathy has been recorded. Infusions of intravenous albumin may provide temporary effectiveness but usually this exogenous source is also metabolized or lost. Management of lower limb edema is also important, usually with elastic bandages or stockings.

The long-term natural history of intestinal lymphangiectasia has been evaluated only to a limited extent. In a recent report[56], dietary intervention appeared to be effective in most cases, particularly in pediatric-onset disease. In the same report, 5% appeared to develop malignant transformation with lymphoma with the average duration to lymphoma diagnosis being over 30 years.

Peer reviewer: Ioannis A Voutsadakis, MD, PhD, Department of Medical Oncology, University Hospital of Larissa, Larissa 41110, Greece

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Waldmann TA, Steinfeld JL, Dutcher TF, Davidson JD, Gordon RS Jr. The role of the gastrointestinal system in "idiopathic hypoproteinemia". Gastroenterology. 1961;41:197-207. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Freeman HJ. Small intestinal mucosal biopsy for investigation of diarrhea and malabsorption in adults. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2000;10:739-753, vii. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Hart MH, Vanderhoof JA, Antonson DL. Failure of blind small bowel biopsy in the diagnosis of intestinal lymphangiectasia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987;6:803-805. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Hokari R, Kitagawa N, Watanabe C, Komoto S, Kurihara C, Okada Y, Kawaguchi A, Nagao S, Hibi T, Miura S. Changes in regulatory molecules for lymphangiogenesis in intestinal lymphangiectasia with enteric protein loss. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e88-e95. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Schmider A, Henrich W, Reles A, Vogel M, Dudenhausen JW. Isolated fetal ascites caused by primary lymphangiectasia: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:227-228. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Vignes S, Bellanger J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (Waldmann's disease). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:5. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Kim JH, Bak YT, Kim JS, Seol SY, Shin BK, Kim HK. Clinical significance of duodenal lymphangiectasia incidentally found during routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:510-515. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Rao R, Shashidhar H. Intestinal lymphangiectasia presenting as abdominal mass. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:522-523, discussion 523. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Colizza S, Tiso B, Bracci F, Cudemo RG, Bigotti A, Crisci E. Cystic lymphangioma of stomach and jejunum: report of one case. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:169-176. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Camilleri M, Satti MB, Wood CB. Cystic lymphangioma of the colon. Endoscopic and histologic features. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:813-816. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Davis M, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Haque AK. Cavernous lymphangioma of the duodenum: case report and review of the literature. Gastrointest Radiol. 1987;12:10-12. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Lenzhofer R, Lindner M, Moser A, Berger J, Schuschnigg C, Thurner J. Acute jejunal ileus in intestinal lymphangiectasia. Clin Investig. 1993;71:568-571. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Perisic VN, Kokai G. Coeliac disease and lymphangiectasia. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:134-136. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Iida F, Wada R, Sato A, Yamada T. Clinicopathologic consideration of protein-losing enteropathy due to lymphangiectasia of the intestine. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1980;151:391-395. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Herfarth H, Hofstädter F, Feuerbach S, Jürgen Schlitt H, Schölmerich J, Rogler G. A case of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding and protein-losing gastroenteropathy. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:288-293. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Baichi MM, Arifuddin RM, Mantry PS. Acute gastrointestinal bleeding from focal duodenal lymphangiectasia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:1269-1270. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Lom J, Dhere T, Obideen K. Intestinal lymphangiectasia causing massive gastrointestinal bleed. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:74-75. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Macdonald J, Porter V, Scott NW, McNamara D. Small bowel lymphangiectasia and angiodysplasia: a positive association; novel clinical marker or shared pathophysiology? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:610-614. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Kalman S, Bakkaloğlu S, Dalgiç B, Ozkaya O, Söylemezoğlu O, Buyan N. Recurrent hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with intestinal lymphangiectasia. J Nephrol. 2007;20:246-249. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Sahli H, Ben Mbarek R, Elleuch M, Azzouz D, Meddeb N, Chéour E, Azzouz MM, Sellami S. Osteomalacia in a patient with primary intestinal lymphangiectasis (Waldmann's disease). Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:73-75. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Lu YY, Wu JF, Ni YH, Peng SS, Shun CT, Chang MH. Hypocalcemia and tetany caused by vitamin D deficiency in a child with intestinal lymphangiectasia. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108:814-818. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Samman PD, White WF. The “yellow nail” syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:153-157. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Bereket A, Lowenheim M, Blethen SL, Kane P, Wilson TA. Intestinal lymphangiectasia in a patient with autoimmune polyglandular disease type I and steatorrhea. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:933-935. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Makharia GK, Tandon N, Stephen Nde J, Gupta SD, Tandon RK. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia as a component of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type I: a report of 2 cases. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007;26:293-295. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Cammarota G, Cianci R, Gasbarrini G. High-resolution magnifying video endoscopy in primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: a new role for endoscopy? Endoscopy. 2005;37:607. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Kim JH, Bak YT, Kim JS, Seol SY, Shin BK, Kim HK. Clinical significance of duodenal lymphangiectasia incidentally found during routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:510-515. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Maunoury V, Plane C, Cortot A. Lymphangiectasia in Waldmann's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:xxxiii. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Danielsson A, Toth E, Thorlacius H. Capsule endoscopy in the management of a patient with a rare syndrome--yellow nail syndrome with intestinal lymphangiectasia. Gut. 2006;55:196, 233. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Fang YH, Zhang BL, Wu JG, Chen CX. A primary intestinal lymphangiectasia patient diagnosed by capsule endoscopy and confirmed at surgery: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2263-2265. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Fry LC, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P, Monkemuller K. Utility of double-balloon enteroscopy for the evaluation of malabsorption. Dig Dis. 2008;26:134-139. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Bellutti M, Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Dombrowski F, Malfertheiner P. Characterization of yellow plaques found in the small bowel during double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1059-1063. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Liu NF, Lu Q, Wang CG, Zhou JG. Magnetic resonance imaging as a new method to diagnose protein losing enteropathy. Lymphology. 2008;41:111-115. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Strober W, Wochner RD, Carbone PP, Waldmann TA. Intestinal lymphangiectasia: a protein-losing enteropathy with hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphocytopenia and impaired homograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 1967;46:1643-1656. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Weiden PL, Blaese RM, Strober W, Block JB, Waldmann TA. Impaired lymphocyte transformation in intestinal lymphangiectasia: evidence for at least two functionally distinct lymphocyte populations in man. J Clin Invest. 1972;51:1319-1325. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Heresbach D, Raoul JL, Genetet N, Noret P, Siproudhis L, Ramée MP, Bretagne JF, Gosselin M. Immunological study in primary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Digestion. 1994;55:59-64. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Fuss IJ, Strober W, Cuccherini BA, Pearlstein GR, Bossuyt X, Brown M, Fleisher TA, Horgan K. Intestinal lymphangiectasia, a disease characterized by selective loss of naive CD45RA+ lymphocytes into the gastrointestinal tract. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:4275-4285. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | Vignes S, Carcelain G. Increased surface receptor Fas (CD95) levels on CD4+ lymphocytes in patients with primary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:252-256. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Chiu NT, Lee BF, Hwang SJ, Chang JM, Liu GC, Yu HS. Protein-losing enteropathy: diagnosis with (99m)Tc-labeled human serum albumin scintigraphy. Radiology. 2001;219:86-90. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Maconi G, Molteni P, Manzionna G, Parente F, Bianchi Porro G. Ultrasonographic features of long-standing primary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Eur J Ultrasound. 1998;7:195-198. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 40. | Mazzie JP, Maslin PI, Moy L, Price AP, Katz DS. Congenital intestinal lymphangiectasia: CT demonstration in a young child. Clin Imaging. 2003;27:330-332. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. | Yang DM, Jung DH. Localized intestinal lymphangiectasia: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:213-214. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Liu NF, Lu Q, Wang CG, Zhou JG. Magnetic resonance imaging as a new method to diagnose protein losing enteropathy. Lymphology. 2008;41:111-115. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | So Y, Chung JK, Seo JK, Ko JS, Kim JY, Lee DS, Lee MC. Different patterns of lymphoscintigraphic findings in patients with intestinal lymphangiectasia. Nucl Med Commun. 2001;22:1249-1254. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 44. | Freeman HJ. Tropheryma whipplei infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2078-2080. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 45. | Chung HV, Ramji A, Davis JE, Chang S, Reid GD, Salh B, Freeman HJ, Yoshida EM. Abdominal pain as the initial and sole clinical presenting feature of systemic lupus erythematosus. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:111-113. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 46. | Broder S, Callihan TR, Jaffe ES, DeVita VT, Strober W, Bartter FC, Waldmann TA. Resolution of longstanding protein-losing enteropathy in a patient with intestinal lymphangiectasia after treatment for malignant lymphoma. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:166-168. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 47. | Laharie D, Degenne V, Laharie H, Cazorla S, Belleannee G, Couzigou P, Amouretti M. Remission of protein-losing enteropathy after nodal lymphoma treatment in a patient with primary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:1417-1419. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 48. | Shpilberg O, Shimon I, Bujanover Y, Ben-Bassat I. Remission of malabsorption in congenital intestinal lymphangiectasia following chemotherapy for lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1993;11:147-148. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 49. | Bouhnik Y, Etienney I, Nemeth J, Thevenot T, Lavergne-Slove A, Matuchansky C. Very late onset small intestinal B cell lymphoma associated with primary intestinal lymphangiectasia and diffuse cutaneous warts. Gut. 2000;47:296-300. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 50. | Jeffries GH, Chapman A, Sleisenger MH. Low-fat diet in intestinal lymphangiectasia. Its effect on albumin metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1964;270:761-766. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Wen J, Tang Q, Wu J, Wang Y, Cai W. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: four case reports and a review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3466-3472. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 52. | Aoyagi K, Iida M, Matsumoto T, Sakisaka S. Enteral nutrition as a primary therapy for intestinal lymphangiectasia: value of elemental diet and polymeric diet compared with total parenteral nutrition. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1467-1470. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 53. | MacLean JE, Cohen E, Weinstein M. Primary intestinal and thoracic lymphangiectasia: a response to antiplasmin therapy. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1177-1180. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 54. | Klingenberg RD, Homann N, Ludwig D. Type I intestinal lymphangiectasia treated successfully with slow-release octreotide. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1506-1509. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 55. | Chen CP, Chao Y, Li CP, Lo WC, Wu CW, Tsay SH, Lee RC, Chang FY. Surgical resection of duodenal lymphangiectasia: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2880-2882. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 56. | Wen J, Tang Q, Wu J, Wang Y, Cai W. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: four case reports and a review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3466-3472. [Cited in This Article: ] |