Published online Sep 15, 2020. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v12.i9.1073

Peer-review started: April 24, 2020

First decision: July 4, 2020

Revised: April 24, 2020

Accepted: August 16, 2020

Article in press: August 16, 2020

Published online: September 15, 2020

Breast metastases from colorectal cancer (CRC) are very uncommon. There is no unanimous consensus regarding the best treatment for this rare condition, and management is, especially in elderly patients, limited to diagnosis and palliative care. Capecitabine, an oral fluoropyrimidine derivative, might be helpful in controlling the disease and may be a treatment option for patients unable to receive more aggressive chemotherapy.

We report a case of synchronous massive breast metastasis from CRC in an 85 year old patient who came to the hospital presenting a huge mass originating from the axillary extension of the right breast. A whole body computed tomography also showed a mass in the right colon. The patient underwent a simple right mastectomy along with right hemicolectomy. The resected breast showed massive metastasis from CRC with intense and homogeneous nuclear CDX2 staining, while the colon specimen revealed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma stage pT4a pN0 pM1 (breast) (Tumor Node Metastasis 2017). Three months later she developed a subcutaneous mass at the site of the previous mastectomy. An ultrasound guided biopsy was carried out again and revealed a metastasis from CRC. The patient then started treatment with capecitabine plus bevacizumab, obtaining stable disease (RECIST criteria) and a clinical benefit after 3 mo of therapy.

In our experience, capecitabine and bevacizumab may be a useful treatment option for breast metastases from primary CRC in elderly patients.

Core Tip: Colorectal cancer (CRC) metastases to the breast is a rare occurrence, and patients with breast metastases from CRC generally have a poor prognosis. Early recognition and full characterization of the disease and patient can potentially optimize the treatment plan. Capecitabine and bevacizumab combination may provide a useful option for breast metastases from primary CRC in elderly patients.

- Citation: Taccogna S, Gozzi E, Rossi L, Caruso D, Conte D, Trenta P, Leoni V, Tomao S, Raimondi L, Angelini F. Colorectal cancer metastatic to the breast: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2020; 12(9): 1073-1079

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v12/i9/1073.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v12.i9.1073

Breast tumors are mostly primary, while breast metastases are rare and often derive from contralateral primary mammary cancer. Breast metastases from other tumors are quite rare and account for only 0.5%-3% of all breast metastasis[1,2]. For colorectal cancer (CRC) metastatic to the breast, the differential diagnosis between rare non-mammary breast metastases and primary cancer is crucial because of the completely different approach in management and prognosis[3]. Patients with breast metastases from CRC generally have a poor prognosis, and the management is palliative. Here, we describe an elderly patient treated with capecitabine plus bevacizumab for breast metastasis from CRC.

A 85-year-old female diagnosed with breast metastases from primary CRC.

Patient with no previous history of breast surgery or irradiation had a clinical symptomatology characterized by a painful right breast mass.

The patient’s previous medical history was unremarkable.

Clinical examination evidenced a painful right breast mass of 10 cm × 5 cm. Furthermore, the patient complained of epigastric abdominal pain and had hypoactive intestinal sounds (Figure 1).

Blood analysis revealed a mild leukocytosis 10 × 109/L with predominant neutrophils (70%) and normal hematocrit and platelet counts. Serum C-reactive protein was within the normal range (< 0.8 mg/dL), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was at 30 mm/h. The blood biochemistries as well as urine analysis were normal. Both carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 levels were elevated (carcinoembryonic antigen 32.4 ng/mL, carbohydrate antigen 19-9: 526 U/mL).

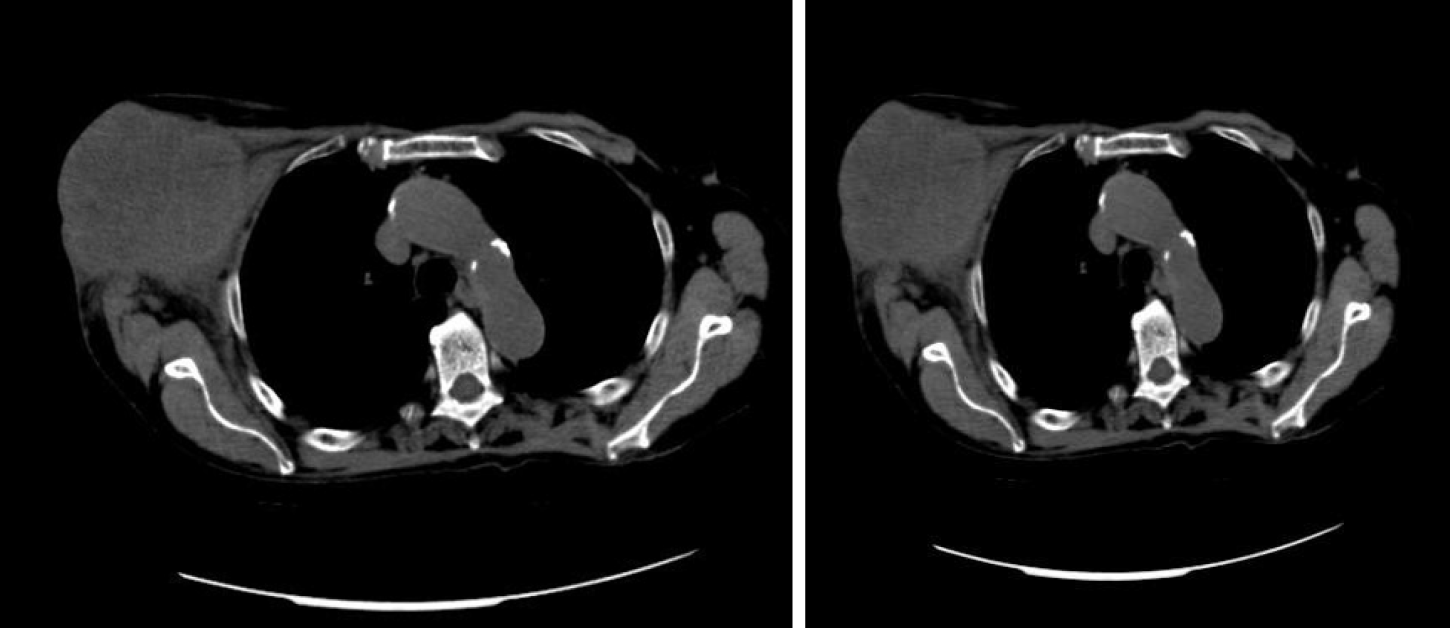

A total body computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 11 cm × 6 cm mass originating from the axillary extension of the right breast and a 3 cm ascending colon lesion. No other obvious lesions were appreciable (Figure 2).

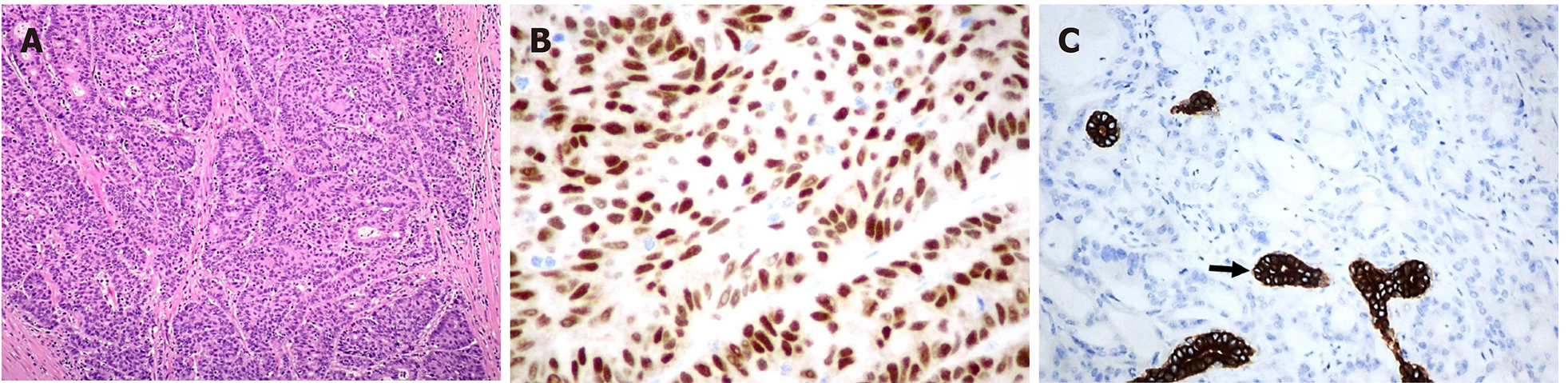

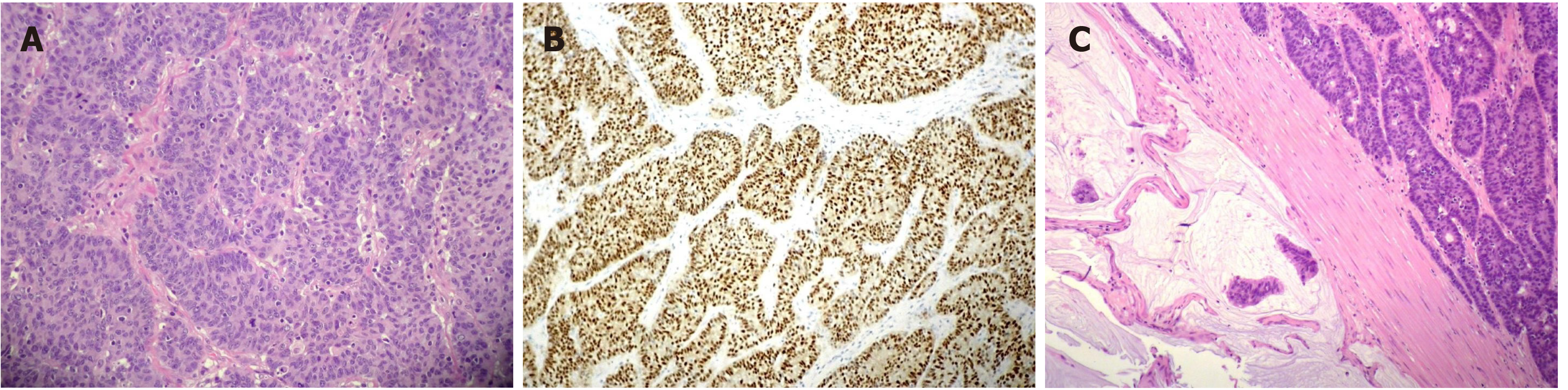

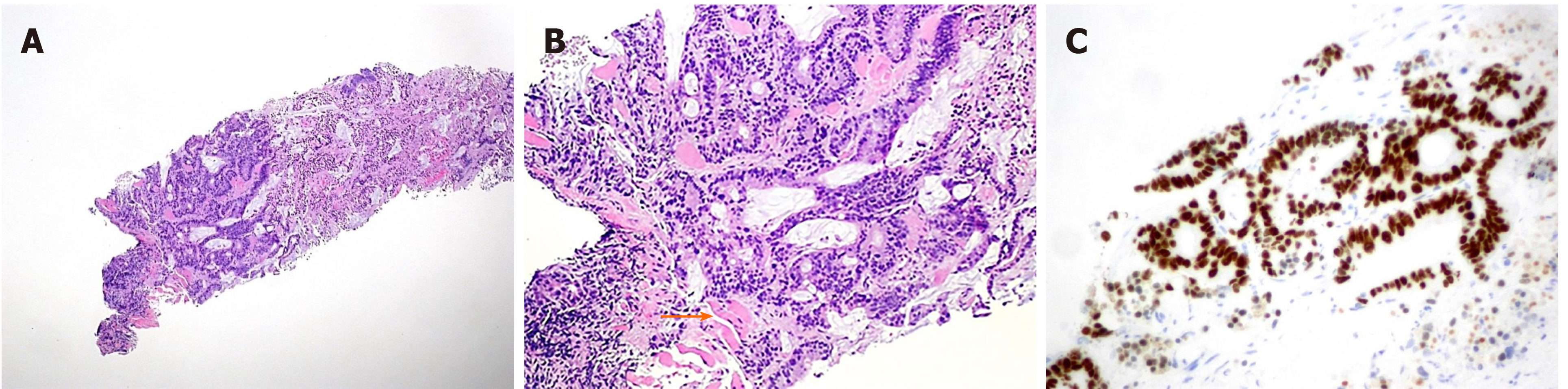

The pathological evaluation of the resected breast was consistent with a necrotic adenocarcinoma extensively infiltrating the mammary parenchyma. The neoplasia was morphologically compatible with intestinal origin, infiltrating and ulcerating the skin and was present on the plan of deep resection (Figure 3A-C). Histological examination of the colon revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, G3, with areas of solid growth and with mucinous aspects (WHO 2010), fully infiltrating the viscera up to the serosa. Nineteen locoregional lymph nodes, the omentum and surgical resection margins were free from neoplastic infiltration (immunohistochemical evaluation performed with CDX2, Syn, CD56, CroA, ki67). Pathological Tumor Node Metastasis results were as follows: pT4a, pN0, pM1a (breast); Stage: IV a; G3; R0 (UICC 2017) (Figure 4A-C). Mutational assessment with polymerase chain reaction was conducted for K-RAS, N-RAS and B-RAF, and a V600E [c. 1977T>A; p. (Val600 Glu)] B-RAF mutation was evidenced on primary tumor. In the following few weeks, while recovering from the surgery, she had a clinical worsening with upper right hemitorax pain, asthenia and a rather evident growth of a mass at the site of the previous mastectomy that extended toward the adjacent right axilla and with evidence of skin neoplastic ulcerative recurrence. CT reassessment showed a mass in the right axillary region (44 mm × 48 mm × 45 mm). She was admitted to hospital where a biopsy of the suspected skin recurrence was performed that showed again metastasis from intestinal adenocarcinoma bringing the same B-RAF mutation, V600E [c. 1977T>A; p. (Val600 Glu)] with high proliferation rate (Ki 67%: 95%); ER/PGR/HER 2 were negative (Figure 5A-C). After 4 wk, a new CT performed showed further and fast progression of the chest mass now involving the entire axilla (90 mm × 85 mm × 100 mm vs 44 mm × 48 mm × 45 mm).

Patient started chemotherapy according to capecitabine- bevacizumab schedule (reference).No significant treatment related toxicity was recorded [(> 2 CTCAE 4.0), ref].

Clinical examination after three cycles of treatment showed stable disease according to RECIST criteria with some clinical improvement of the neoplastic skin lesion and a substantial clinical benefit on pain and asthenia.

CRC is the third most frequent malignant disease in the world[4]. Regional lymph nodes, liver, lungs and peritoneum are the most common metastatic sites[5]. CRC metastasis to the breast is a very unusual occurrence, but it should be kept in mind when a breast mass is diagnosed in a patient with a previous or concurrent diagnosis of CRC. In this case, the pathological evaluation of the resected breast was consistent with a necrotic adenocarcinoma extensively infiltrating the mammary parenchyma, morphologically compatible with intestinal origin. Further histological examination of the colon revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, fully infiltrating the viscera up to the serosa. Pathological Tumor Node Metastasis results were as follows: pT4a, pN0, pM1a (breast); Stage: IV a; G3; R0. Breast involvement by extramammary malignant neoplasms is distinctly unusual. According to McCrea et al[2], metastasis can occur through two routes: Cross-lymphatic (metastatic from contralateral breast) and blood-borne. Melanoma is the most common source of bloodborne metastases to the breast, followed by lung cancer, sarcomas and ovarian cancer in decreasing order of frequency. Fewer lesions arise from the gastrointestinal (such as colon rectal cancer) and genitourinary tracts. Usually mammary metastases from extramammary tumors present as clinically palpable quickly growing mobile masses. Generally, they do not result in nipple retraction and/or bleeding[6,7].

CRC metastasis to the breast is a very unusual occurrence, and, especially because of the rarity of this phenomenon, there is little information in the literature that can clarify the etiopathogenesis. It is essential to provide an accurate diagnosis, although the prognosis of these patients is often severe. Immunohistochemistry allows a safe differentiation between primary breast adenocarcinoma and metastasis from colorectal adenocarcinoma in the breast; most CRC are generally CK7 negative and CK20 positive, whereas most primary breast cancers are CK7 positive and CK20 negative[8]. Positive immunostaining for CDX2, as in our patient, is a highly sensitive and specific marker for CRC[9].

In the patient we are describing, we searched for all RAS and BRAF mutations on the primary colon cancer and on the breast metastasis, and we were able to demonstrate the same BRAF mutation V600E [c. 1977T>A; p. (Val600 Glu)] on both specimens. This fact further confirms both the origin of the breast neoplasia from the colon adenocarcinoma and the ability in this case of the neoplasia to retain the same mutational asset at the metastatic site. We have been able to find only 45 cases of breast metastases from primary CRC in a review of the literature (Table 1). The average age of patients was 52 years; most of the cases involved neoplasms originating in the left colon, while both the breasts were almost equally involved by the metastatic spread (left, 18; right, 21; bilateral, 5).

| Age/yr | Size/cm | Colorectal cancer site | Metastasis in other organs | Time of survival from diagnosis ofbreast metastasis | |

| Mcintosh | 44 | ? | ? | ? | 4 mo |

| Lear | 67 | ?/3 | ? | ? | ?/ > 6 yr |

| Nielsen | 68 | 2/4/3 | ? | Yes | 6 mo/4 mo |

| Alexander | 59 | ? | Rectum | Yes | 43 mo |

| Bhirangi | 28 | 2 | Colon | No | 18 mo |

| Muttarak | 86 | ? | Colon | ? | ? |

| Lal | 36 | ? | Rectum | Yes | 4 mo |

| Ozakyol | 69 | 3 | Colon | Yes | 6 mo |

| Meloni | 42 | 2 | Colon | No | 6 mo |

| Sironi | 77 | ? | Colon | Yes | ? |

| Oksüzoglu | 52 | 1, 4 | Colon | No | 2 mo |

| Mihai | 53 | 1 | Rectum | Yes | 4 mo |

| Fernandez | 40 | 4 | Colon | Yes | 6 mo |

| Rossen | 81 | 2, 5 | Colon | No | 16 mo |

| Hisham | 32 | 4 | Rectum | Yes | 0.5 mo |

| Wakeham | 45/74 | 2, 2/2/4/6 | Rectum | Yes | ?/? |

| Sanchez | 36 | 6 | Rectum | No | ? |

| Li | 54 | 3 | Rectum | Yes | < 10 mo |

| Singh | 42 | 5 | Rectum | Yes | 2 mo |

| Ho | 50 | 1, 5 | Colon | Yes | 12 mo |

| Del | 43 | 4, 5 | Colon | Yes | ? |

| Barthelmes | 78 | 1 | Colon | Yes | 4 mo |

| Cabibi | 76 | 1, 6 | Colon | Yes | > 18 mo |

| Noh | 63 | 1, 8 | Colon | Yes | ? |

| Perin | 46 | 1 | Colon | Yes | 16 mo |

| Shackelford | 44 | 11 | Colon | Yes | ? |

| Selcubiricik | 37 | 1 | Colon | No | ? |

| Wang | 38 | 6 | Rectum | Yes | 2 mo |

| Santiago | 76 | 1, 2 | Colon | Yes | 11 yr |

| Makhdoomi | 28 | ? | Rectum | No | > 2 mo |

| Vakili | 38 | 9 | Colon | Yes | > 8 mo |

| Ahmad | 28 | 2 | Rectum | Yes | ? |

| Avani | 55 | 1 | Colon | Yes | 6 mo |

| Kothaida | 45/56 | 0,6/0,9/1,4 | Colon | Yes | ?/? |

| Cheng | 37 | 3 | Colon | Yes | 4 mo |

| Zhang | 80 | 1, 8 | Colon | No | > 10 mo |

| Shah | 49 | 4, 2 | Rectum | No | ? |

| Hejazi | 47 | 1, 7 | Rectum | No | 12 mo |

| Aribas | 21 | ? | Rectum | Yes | 12 mo |

| Tsung | 82 | 3, 3 | Colon | Yes | ? |

| D'Aniello | 53 | 2, 6 | Colon | Yes | > 14 mo |

| Hsieh | 44 | 2 | Rectum | Yes | 7 mo |

The average time from CRC diagnosis to breast metastases is 28.3 mo. In one case, breast metastases were detected 10 years after the initial CRC. Average survival time after detection of breast metastases is 14.9 mo, with only one case surviving more than 5 years. In three cases, metastases were synchronous with other metastatic organ lesions; in 12 patients, the breast was the only site of metastasis. Patients with breast metastases from CRC generally have a poor prognosis; often the disease has an aggressive behavior, and there is no unanimous consent on the best treatment for this condition.

A majority of these patients received standardized management of their primary CRC[3], even if according to a recent report, the management of metastatic breast mass from CRC is often diagnostic and palliative[1]. Oral capecitabine, which was prescribed as palliative chemotherapy, might further slow the growth of the patient's metastasis in the breast[10]. In our case, this treatment was selected considering patient's advanced age, clinical status, the negative prognosis and the supposed resistance to anti-epithelial growth factor receptor drugs due to B-RAF mutation (ref). Patient started treatment according to capecitabine and bevacizumab schedule (ref). Clinical examination after three cycles of treatment resulted in stable disease (RECIST criteria) and in a substantial clinical benefit with minor chemotherapy toxicity.

CRC metastasis to the breast is a rare occurrence, and patients often have a poor prognosis because of the advanced age, performance status, comorbidity and aggressive behavior of the disease.

The treatment strategy should be individualized according to patient and disease characteristics, including All-RAS and B-RAF mutational status.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Thomopoulos K S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Tsung SH. Metastasis of Colon Cancer to the Breast. Case Rep Oncol. 2017;10:77-80. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | McCrea ES, Johnston C, Haney PJ. Metastases to the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;141:685-690. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 116] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hsieh TC, Hsu CW. Breast metastasis from colorectal cancer treated by multimodal therapy: Case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e18016. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mattiuzzi C, Sanchis-Gomar F, Lippi G. Concise update on colorectal cancer epidemiology. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:609. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 152] [Article Influence: 30.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7-30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11573] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12478] [Article Influence: 2079.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 6. | Vergier B, Trojani M, de Mascarel I, Coindre JM, Le Treut A. Metastases to the breast: differential diagnosis from primary breast carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1991;48:112-116. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 138] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hajdu SI, Urban JA. Cancers metastatic to the breast. Cancer. 1972;29:1691-1696. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Kende AI, Carr NJ, Sobin LH. Expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract. Histopathology. 2003;42:137-140. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 85] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Noh KT, Oh B, Sung SH, Lee RA, Chung SS, Moon BI, Kim KH. Metastasis to the breast from colonic adenocarcinoma. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;81 Suppl 1:S43-S46. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rossi D, Alessandroni P, Catalano V, Giordani P, Fedeli SL, Fedeli A, Baldelli AM, Casadei V, Ceccolini M, Catalano G. Safety profile and activity of lower capecitabine dose in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2007;7:857-860. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |