Published online Oct 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i10.514

Revised: August 28, 2013

Accepted: September 3, 2013

Published online: October 16, 2013

Endoscopic ultrasonography is the most accurate procedure for the evaluation of subepithelial lesions. The finding of a homogeneous, hyperechoic, well-delimited lesion, originating from the third layer of the gastrointestinal tract (submucosa) suggests a benign tumor, generally lipoma. As other differential diagnoses have not been reported, echoendoscopists might not pursue a definitive pathological diagnosis or follow-up the patient. This case series aims to broaden the spectrum of differential diagnosis for duodenal hyperechoic third layer subepithelial lesions by providing four different and relevant pathologies with this echoendoscopic pattern.

Core tip: This case series reports four different and relevant pathologies with an echoendoscopic pattern usually suggestive of lipoma.

- Citation: Figueiredo PC, Pinto-Marques P, Mendonça E, Oliveira P, Brito M, Serra D. Duodenal subepithelial hyperechoic lesions of the third layer: Not always a lipoma. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(10): 514-518

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i10/514.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i10.514

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has long been considered the most accurate procedure for the evaluation of subepithelial lesions[1-3]. It provides important information, namely the layer of origin, size, borders and echogenic structure. Using Doppler findings it may also differentiate vascular structures from cysts or assess the tumor blood supply. These findings allow for a presumptive diagnosis in most cases, although histopathology remains the gold standard[2].

Gastrointestinal (GI) lipomas are benign tumors that occur anywhere along the gut, most commonly in the colon[4]. The typical EUS finding is a homogeneous, hyperechoic, well-delimited lesion, originating from the third layer of the GI tract (submucosa)[3,5]. The only differential diagnosis for this EUS pattern reported in the literature is Brunner’s gland hamartoma[5,6].

This case series aims to broaden the spectrum of EUS differential diagnosis for duodenal hyperechoic third layer subepithelial lesions.

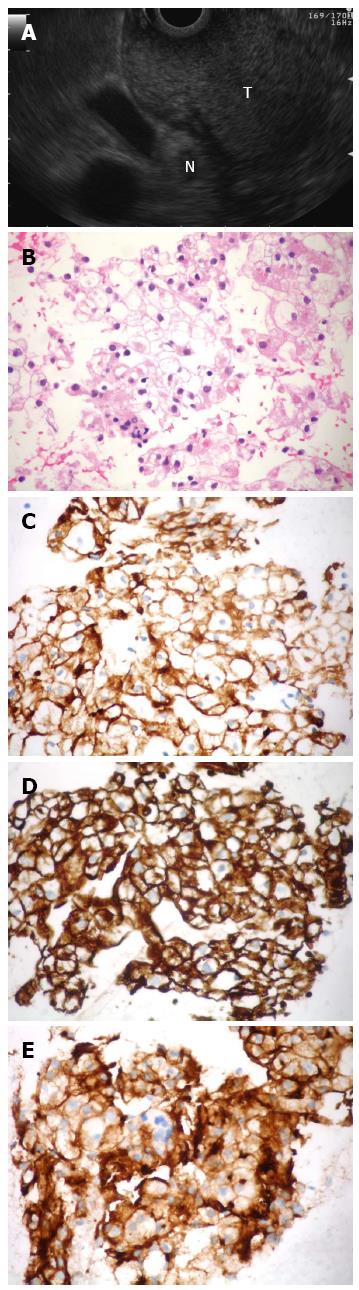

A 58-year-old woman was admitted for melena and upper GI endoscopy revealed an ulcerated mass in the duodenal bulb. Biopsies using “bite-on-bite” technique were inconclusive. EUS with a linear echoendoscope (Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan) showed a well-delimited hyperechoic mass, apparently originating from the third layer at the bulb (Figure 1A). Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) was performed with a 22-gauge EZ Shot needle (Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan). FNA smear and cellblock sections showed clear cell aggregates with positive immunostaining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, vimentin and CD10, which were consistent with an epithelial carcinoma of renal origin (Figure 1B-E). Three years before the patient had a left kidney nephrectomy for a Grawitz tumor and was referred for cephalic pancreatoduodenectomy to treat the disease recurrence.

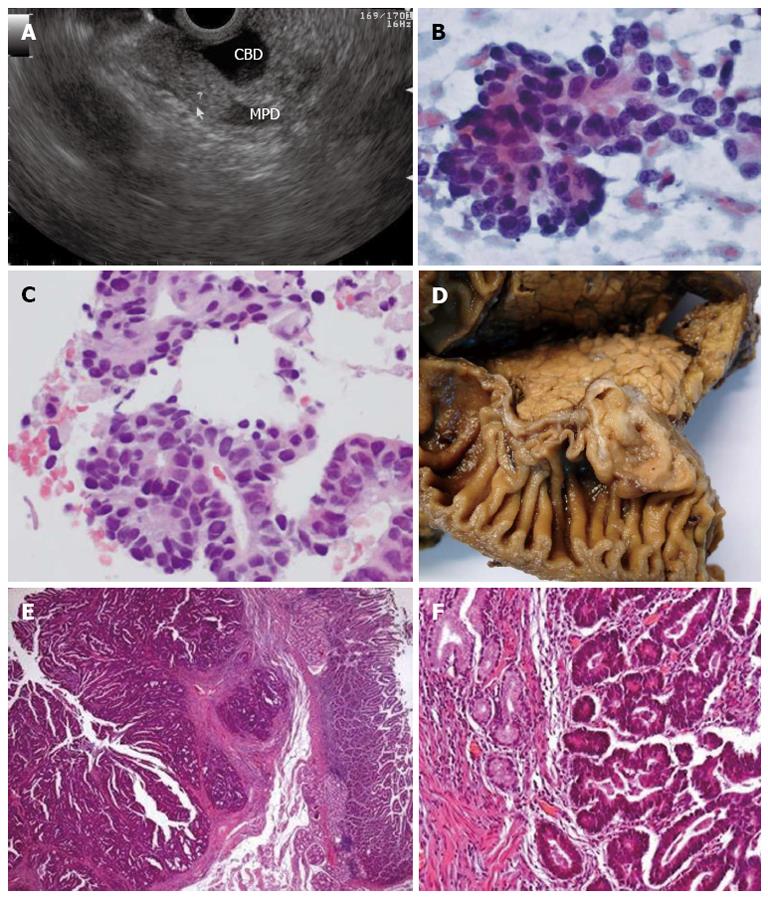

A 64-year-old man presented with jaundice at the emergency department. An abdominal US and CT scan showed dilated bile ducts down to the level of the ampullary region, where a polypoid mass was found. Using a linear echoendoscope a mildly hyperechoic homogeneous lesion was found on the duodenal submucosa, adjacent to the ampulla, compressing the bile duct (Figure 2A). FNA with a 25-gauge EZ Shot needle (Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan) retrieved a cytology sample consistent with adenocarcinoma (Figure 2B, C). The patient was submitted to cephalic pancreatoduodenectomy which confirmed the diagnosis of ampullary carcinoma (Figure 2D-F).

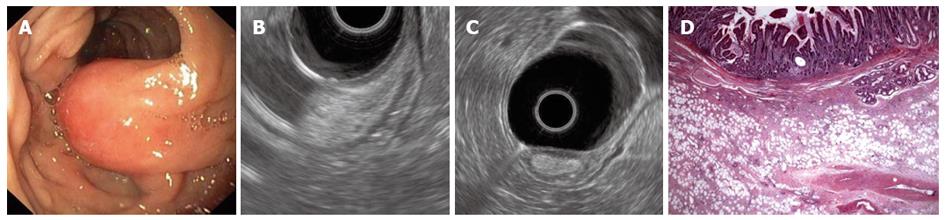

A 62-year-old man was admitted for melena and upper GI endoscopy revealed an ulcerated semipedunculated polyp in the second portion of the duodenum (Figure 3A). EUS, performed using a radial echoendoscope, showed a homogeneous hyperechoic polypoid lesion originating from the submucosa (Figure 3B, C). Following polypectomy, histopathological examination unveiled fibroadipose tissue covered by intestinal mucosa, which was consistent with a hamartomatous polyp (Figure 3D).

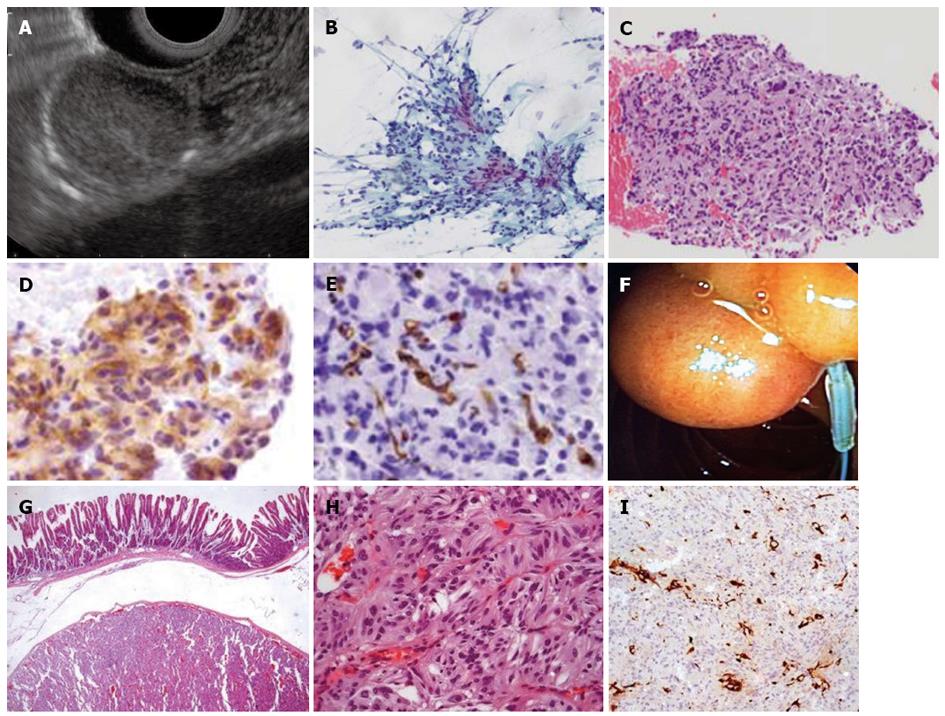

A 51-year-old woman was submitted to an upper GI endoscopy for dyspepsia. A 20 mm subepithelial lesion was found on the posterior wall of the second part of the duodenum. On linear EUS, this was shown to be a well-delimited slightly hyperechoic lesion apparently originating from the submucosa (Figure 4A). A tissue sample was obtained using a 22-gauge ProCore needle (Cook Endoscopy Inc, Limerick, Ireland) (Figure 4B-E). Cytopathological examination suggested a possible gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) which led to the decision to perform endoscopic resection (Figure 4F). Further histopathological analysis of the resected tumor brought about another diagnosis-gangliocytic paraganglioma (Figure 4G-I).

Although EUS does not provide gastroenterologists with a definitive diagnosis for subepithelial lesions, the ultrasonographic findings and knowledge of the epidemiology allow for an educated guess in many situations. This, along with the likelihood of malignancy, guides management decisions regarding biopsy and resection.

Both lipomas and Brunner’s gland hamartomas are regarded as benign tumours, which are usually asymptomatic[7,8]. Given their benign nature, treatment is only recommended if they become symptomatic[9]. Moreover, in the absence of other differential diagnosis for hyperechoic lesions of the third layer of the GI tract, the ecoendoscopist might be tempted not to obtain a tissue sample or even not follow-up the patient.

In our case series, two subepithelial lesions presented with bleeding and a third one with jaundice. EUS favored the diagnosis of lipoma in all of these lesions and resection was required. In the first two cases, surgery was the preferred approach due to the tumors characteristics-size, ulceration and location. The surgical team required a histopathological evaluation to confirm the diagnosis and establish the therapeutic strategy, therefore EUS with FNA was performed. In the third case, the tumor was pedunculated and endoscopic resection was feasible, thus FNA was not required.

The fourth case was an incidental lesion. EUS features were felt suspicious for lipoma although the pattern was not typical. Based on these findings and our prior experience with the first three cases, a FNA was performed. The diagnosis was GIST, which is a fairly uncommon diagnosis in the third layer[3]. Management options were discussed with the patient and the decision for resection was based on the tumor’s size (2 cm), location (small bowel confers worse prognosis) as well as the patient’s wish[10]. The surgical specimen pathology report showed the lesion to be a gangliocytic paraganglioma-an exceedingly rare entity[11]. Previous EUS reports described it as a hypoechoic or isoechoic homogeneous lesion, in the proximity of the duodenal papilla[12,13]. Its characteristic triphasic microscopic appearance (epithelioid cells, spindle cells, and ganglion cells) histological appearance might account for our inability to differentiate it from a GIST on FNA[14].

In conclusion, this case series presents relevant and previously unreported differential diagnosis for duodenal hyperechoic subepithelial lesions in the third layer. The EUS operator should always take time to assess the transition zone to assess the layer of origin and, in our opinion, have a low threshold to perform FNA, namely, if the EUS features are felt not typical.

P- Reviewer Meier PN S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Liu XM

| 1. | Rösch T, Lorenz R, Dancygier H, von Wickert A, Classen M. Endosonographic diagnosis of submucosal upper gastrointestinal tract tumors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:1-8. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Săftoiu A, Vilmann P, Ciurea T. Utility of endoscopic ultrasound for the diagnosis and treatment of submucosal tumors of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2003;12:215-229. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Sakamoto H, Kitano M, Kudo M. Diagnosis of subepithelial tumors in the upper gastrointestinal tract by endoscopic ultrasonography. World J Radiol. 2010;2:289-297. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Taylor AJ, Stewart ET, Dodds WJ. Gastrointestinal lipomas: a radiologic and pathologic review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155:1205-1210. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Chen HT, Xu GQ, Wang LJ, Chen YP, Li YM. Sonographic features of duodenal lipomas in eight clinicopathologically diagnosed patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2855-2859. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Xu GQ, Wu YQ, Wang LJ, Chen HT. Values of endoscopic ultrasonography for diagnosis and treatment of duodenal protruding lesions. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2008;9:329-334. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kadaba R, Bowers KA, Wijesuriya N, Preston SL, Bray GB, Kocher HM. An unusual cause of gastrointestinal bleeding: duodenal lipoma. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2011;5:183-188. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Abbass R, Al-Kawas FH. Brunner gland hamartoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2008;4:473-475. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Yu HG, Ding YM, Tan S, Luo HS, Yu JP. A safe and efficient strategy for endoscopic resection of large, gastrointestinal lipoma. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:265-269. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | ESMO / European Sarcoma Network Working Group. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23 Suppl 7:vii49-vii55. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 128] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wu GC, Wang KL, Zhang ZT. Gangliocytic paraganglioma of the duodenum: a case report. Chin Med J (Engl). 2012;125:388-389. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Nakamura T, Ozawa T, Kitagawa M, Takehira Y, Yamada M, Yasumi K, Tamakoshi K, Kobayashi Y, Nakamura H. Endoscopic resection of gangliocytic paraganglioma of the minor duodenal papilla: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:270-273. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Assef MS, Carbonari AP, Araki O, Nakao F, Marchetti I, Medeiros MT, Kassab P, Malheiros CA, Rossini LB. Gangliocytic paraganglioma of the duodenal papilla associated with esophagogastric adenocarcinoma. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E165-E166. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Plaza JA, Vitellas K, Marsh WL. Duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma: a radiological-pathological correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2005;9:143-147. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |