Published online Jan 16, 2010. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i1.41

Revised: March 31, 2009

Accepted: April 7, 2009

Published online: January 16, 2010

Whilst ascites is a common presenting complaint in patients with decompensated chronic liver disease and disseminated malignancy, in Crohn’s disease however, it is exceptionally rare. We describe a patient with no prior history of inflammatory bowel or liver disease, presenting with rapid onset gross ascites and scrotal swelling. Further investigations revealed severe hypoalbuminemia and transudative ascitic fluid with normal other liver function tests and a negative liver screen. Computed tomography revealed widespread ascites and pleural effusions with no features of malignancy or portal hypertension, and a small bowel barium series showed features of fistulating small bowel Crohn’s disease. An ileo-colonoscopy confirmed the presence of terminal ileal inflammatory stricture. The patient’s clinical condition and serum albumin improved with a combination of diuretics, elemental diet, antibiotics and oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy.

- Citation: Kia R, White D, Sarkar S. An unusual presentation of fistulating Crohn’s disease: Ascites. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 2(1): 41-43

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v2/i1/41.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v2.i1.41

Crohn’s disease is a chronic, relapsing and remitting inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract, with a prevalence of 140 cases per 100 000 in the West[1]. Common presenting symptoms include diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and fatigue[2]. Ascites as the main presenting complaint in undiagnosed Crohn’s disease is extremely rare and to our knowledge has only been reported once within the literature[3]. However, ascites secondary to conditions associated with Crohn’s disease, such as malignancy and portal hypertension is well recognised[4-6]. We describe a case where a patient with previously undiagnosed fistulating Crohn’s disease presented as an emergency with gross ascites, scrotal swelling and severe hypoalbuminemia. We also highlight the diagnostic features of Crohn’s disease in barium studies and ileo-colonoscopy, which helped in the diagnosis of this atypical case.

A 61-year-old man presented in the emergency department with rapid onset abdominal and scrotal swelling. The only other symptom of note was mild intermittent diarrhea, which had been present since a sigmoid colectomy was performed 5 years previously for a diverticular abscess. He was a non-smoker and past medical history included angina and atrial fibrillation. There was no history of chronic liver disease, alcohol abuse, or any significant family history.

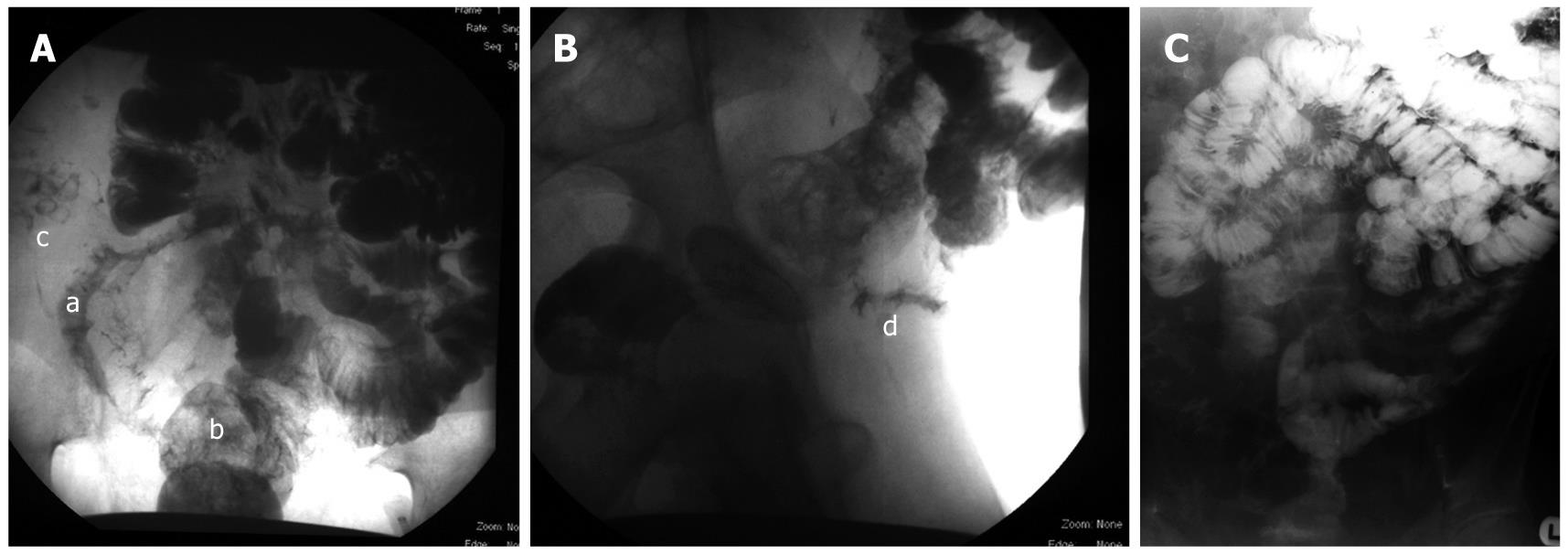

Examination revealed tense ascites, pedal and scrotal edema but no stigmata of liver disease. Blood tests including full blood count, inflammatory markers (CRP/ESR) and liver function tests were normal (total bilirubin 17 μmol/L, alkaline phosphatase 107 IU/L, INR 1.1, aspartate transaminase 30 IU/L) with the exception of severe hypoalbuminemia of 17 g/L. Auto-antibodies, celiac immunology, vasculitic screen and hepatitis serologies were negative. Echocardiogram and 24-h urinary protein excretion were also normal. CT of the thorax and abdomen revealed widespread ascites and pleural effusions with no features of malignancy or portal hypertension. Analysis of the ascitic fluid revealed a transudate with negative microbiology (total white blood cells of 23/mm3) and cytology investigations, and normal amylase. To investigate the intermittent diarrhea and hypoalbuminemia, a gastroscopy with second part duodenal biopsies and colonoscopy with random colonic biopsies were performed, and were essentially normal with the exception of widespread colonic diverticular disease. A small bowel barium series was then performed with the relevant images shown in Figure 1. Figure 1A shows diseased loops of distal ileum (labeled a) with stricture formation and ulceration, as well as premature filling of the rectum (labeled b) in the absence of contrast filling the proximal colon (labeled c), implying a fistula between the ileum and the sigmoid colon (entero-colonic fistula). Figure 1B, is a lateral image demonstrating the diseased terminal ileum (labeled d). Figure 1C, indirectly illustrates the entero-sigmoid fistula with contrast within the small bowel and rectum, but no filling of the rest of the colon, thus suggesting a connection between the small bowel and very distal colon.

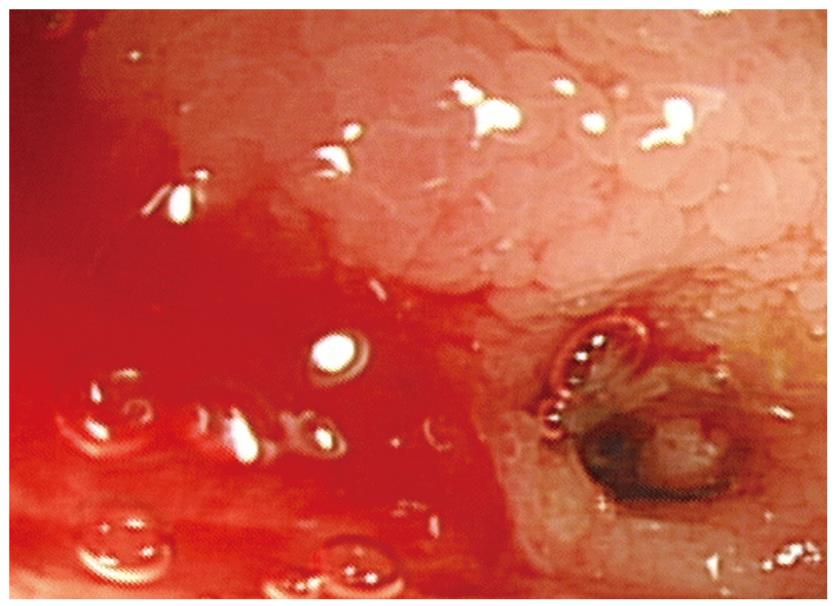

In view of the atypical presentation of gross ascites in a new diagnosis of fistulating Crohn’s disease and the lack of histological confirmation, a colonoscopy was repeated with terminal ileoscopy. This revealed a terminal ileal inflammatory stricture, with mucosal edema as shown on the endoscopic picture in Figure 2. Biopsies from the stricture showed gross distortion of the crypt architecture with focal cryptitis and occasional crypt abscesses, with overall appearances consistent with non-granulomatous ileitis typical of Crohn’s disease.

The patient was treated initially with a combination of diuretics (spironolactone 100 mg daily and furosemide 40 mg daily), elemental diet (3 mo), antibiotics (clarithromycin 500 mg b.i.d. for 3 mo) and high dose oral 5-ASA (Pentasa 4 g daily). Over the course of a few months, the patient’s clinical condition and serum albumin improved with the diuretics weaned off over 6 mo. The patient was maintained solely on high dose 5-ASA preparation (patient was found to be allergic to azathioprine) with no recurrence of ascites 12 mo after his initial presentation.

As previously mentioned, ascites associated with Crohn’s disease has only been reported in very few cases and the majority has been secondary to associated conditions, such as malignancy and portal hypertension[4-6]. In our case, there was no evidence of portal hypertension on cross-sectional imaging (CT showed no splenomegaly or varices) or endoscopy (gastroscopy showed no esophageal varices). Associated malignancy was also excluded as a cause on the basis of negative ascitic fluid cytology, ascitic fluid protein analysis (transudate), and the lack of diagnostic features on CT imaging or upper and lower GI endoscopy.

We attributed the ascites to a hypoalbuminemic state secondary to a protein losing enteropathy as sequelae of small bowel Crohn’s disease. Due to the fistulating nature of the disease there may or may not have been a contribution from small bowel bacterial overgrowth to the protein losing enteropathy. Furthermore, increased small intestinal permeability in Crohn’s disease, possibly secondary to inflammatory cytokines is likely to play a role[7,8]. Paspatis et al[6] also postulated that lymphatic stasis, could be partially involved, though inexplicably most patients do not have ascites.

Our patient had an extremely rare presentation of a relatively common gastrointestinal condition and this case illustrates the various guises that fistulating Crohn’s disease may present with.

Peer reviewer: James F Trotter, MD, Associate Professor, University of Colorado, Division of Gastroenterology, 4200 E. 9th Avenue, b-154, Denver, CO 80262, United States

S- Editor Li JL L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Loftus EV Jr. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504-1517. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Cummings JR, Keshav S, Travis SP. Medical management of Crohn’s disease. BMJ. 2008;336:1062-1066. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Tekin F, Vatansever S, Ozütemiz O, Musoğlu A, Ilter T. Severe exudative ascites as an initial presentation of Crohn’s disease. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2005;16:171-173. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Tsujikawa T, Ihara T, Sasaki M, Inoue H, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T. Effectiveness of combined anticoagulant therapy for extending portal vein thrombosis in Crohn’s disease. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:823-825. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Perosio PM, Brooks JJ, Saul SH, Haller DG. Primary intestinal lymphoma in Crohn’s disease: minute tumor with a fatal outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:894-898. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Paspatis GA, Kissamitaki V, Kyriakakis E, Aretoulaki D, Giannikaki ES, Kokkinaki M, Kabbalo T, Xroniaris N. Ascites associated with the initial presentation of Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1974-1976. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Head K, Jurenka JS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Part II: Crohn’s disease--pathophysiology and conventional and alternative treatment options. Altern Med Rev. 2004;9:360-401. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | MacDonald TT, Murch SH. Aetiology and pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;8:1-34. [Cited in This Article: ] |