Published online Sep 16, 2019. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v11.i9.477

Peer-review started: July 12, 2019

First decision: August 2, 2019

Revised: August 21, 2019

Accepted: August 9, 2019

Article in press: August 9, 2019

Published online: September 16, 2019

Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) is new onset acute pancreatitis after ERCP. This complication is sometimes fatal. As such, PEP should be diagnosed early so that therapeutic interventions can be carried out. Serum lipase (s-Lip) is useful for diagnosing acute pancreatitis. However, its usefulness for diagnosing PEP has not been sufficiently investigated.

This study aimed to retrospectively examine the usefulness of s-Lip for the early diagnosis of PEP.

We retrospectively examined 4192 patients who underwent ERCP at our two hospitals over the last 5 years. The primary outcomes were a comparison of the areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (AUCs) of s-Lip and serum amylase (s-Amy), s-Lip and s-Amy cutoff values based on the presence or absence of PEP in the early stage after ERCP via ROC curves, and the diagnostic properties [sensitivities, specificities, positive predictive values (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV)] of these cutoff values for PEP diagnosis.

Based on the eligibility and exclusion criteria, 804 cases were registered. Over the entire course, PEP occurred in 78 patients (9.7%). It occurred in the early stage after ERCP in 40 patients (51.3%) and in the late stage after ERCP in 38 patients (48.7%). The AUCs were 0.908 for s-Lip [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.880-0.940, P < 0.001] and 0.880 for s-Amy (95%CI: 0.846-0.915, P < 0.001), indicating both are useful for early diagnosis. By comparing the AUCs, s-Lip was found to be significantly more useful for the early diagnosis of PEP than s-Amy (P = 0.023). The optimal cutoff values calculated from the ROC curves were 342 U/L for s-Lip (sensitivity, 0.859; specificity, 0.867; PPV, 0.405; NPV, 0.981) and 171 U/L for s-Amy (sensitivity, 0.859; specificity, 0.763; PPV, 0.277; NPV, 0.979).

S-Lip was significantly more useful for the early diagnosis of PEP. Measuring s-Lip after ERCP could help diagnose PEP earlier; hence, therapeutic interventions can be provided earlier.

Core tip: Serum lipase (s-Lip) is useful for diagnosing acute pancreatitis. The aim of this study was to retrospectively examine the usefulness of s-Lip for the early diagnosis of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (PEP). Based on the eligibility and exclusion criteria, 804 cases were registered. Over the entire course, PEP occurred in 78 patients. The areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUCs) were 0.908 for s-Lip (P < 0.001) and 0.880 for serum amylase (s-Amy) (P < 0.001), indicating both are useful for early diagnosis. By comparing the AUCs, s-Lip was found to be significantly more useful for the early diagnosis of PEP than s-Amy (P = 0.023).

- Citation: Tadehara M, Okuwaki K, Imaizumi H, Kida M, Iwai T, Yamauchi H, Kaneko T, Hasegawa R, Miyata E, Kawaguchi Y, Masutani H, Koizumi W. Usefulness of serum lipase for early diagnosis of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2019; 11(9): 477-485

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v11/i9/477.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v11.i9.477

Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) is new onset acute pancreatitis after ERCP. The consensus criteria and revised Atlanta criteria are international consensus diagnostic criteria[1,2], but they are not unified or ideal in the setting of PEP[3,4,5]. In the consensus criteria, PEP is defined as "new onset or worsened upper abdominal pain; pancreatic amylase and lipase at least three times the upper limit of normal at more than 24 h after ERCP; requiring hospital admission or a prolongation of planned admission”[1]. The limitations include patients in an acute pancreatitis setting or a flare-up of chronic pancreatitis that prevents PEP diagnosis in less than 24 h. In the revised Atlanta criteria, the diagnosis of PEP requires two of the following three criteria: (1) abdominal pain consistent with acute pancreatitis (acute onset of a persistent, severe, epigastric pain often radiating to the back); (2) serum lipase or amylase activity at least three times greater than the upper limit of normal; and (3) characteristic findings of acute pancreatitis on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and, less commonly, magnetic resonance imaging or transabdominal ultrasonography[2]. The limitation is the fact that it is not primarily developed to define PEP. For an assessment of the severity of PEP, it has been reported that the revised Atlanta classification is superior for predicting PEP mortality[6]. The frequency of PEP is reported to be 3% to 15%[7,8,9]. PEP is sometimes fatal, with death occurring in 3% of cases[7]. Therefore, from our experience, PEP needs to be diagnosed early so that therapeutic interventions can be carried out. Normally, acute pancreatitis is diagnosed based on elevated levels of pancreatic enzymes in the blood or urine, accompanied by abdominal pain and imaging findings[3]. However, using serum levels of the pancreatic enzyme amylase is problematic because of its low diagnostic specificity[10,11]. In contrast, serum lipase (s-Lip) has been shown to be the most useful pancreatic enzyme for diagnosing acute pancreatitis, with a sensitivity of 86.5%-100% and specificity of 84.7%-99.0%[11]. Moreover, s-Lip is known to have greater diagnostic power than serum amylase (s-Amy)[12,13]. Furthermore, s-Lip levels increase in the early stages of acute pancreatitis and have been reported to be useful for diagnosing acute pancreatitis when s-Amy levels are normal[13,14]. With regard to ERCP, although there have been reports on how s-Lip and other pancreatic enzyme levels change over time[15,16], the usefulness of s-Lip for the early diagnosis of PEP has yet to be fully investigated.

Thus, we conducted a retrospective study to examine the usefulness of s-Lip and s-Amy for the early diagnosis of PEP.

A total of 4192 patients who underwent ERCP at Kitasato University Hospital and Kitasato University East Hospital over a 5-year period from October 1, 2012 to September 30, 2017 were evaluated for inclusion. The eligibility criteria included having had (1) Both s-Lip and s-Amy measured before ERCP, 3 h post-ERCP, and the next morning; (2) Naïve major duodenal papilla; and (3) Continuous follow-up after ERCP. The exclusion criteria included acute pancreatitis, history of chronic pancreatitis, cholangiojejunostomy for pancreatic disease, and kidney dysfunction with an estimated glomerular filtration rate ≤ 44 mL/min. We excluded cases diagnosed as acute or chronic pancreatitis by imaging.

Our study was reviewed and approved by our institutional ethics committee. Data on the purpose of ERCP, content of examinations, and post-ERCP course were collected from an ERCP database and from the medical records of the Department of Gastroenterology, Kitasato University School of Medicine. Assessments of physical findings, blood test items, and, if necessary, imaging findings that would indicate PEP were conducted 3 h after ERCP and the following morning. The primary outcomes were a comparison of the areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (AUCs) of s-Lip and s-Amy, s-Lip and s-Amy cutoff values based on the presence or absence of PEP in the early stage after ERCP via ROC curves, and comparisons of the diagnostic properties [sensitivities, specificities, positive predictive values (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV)] of these cutoff values for PEP diagnosis.

Naïve major duodenal papilla was defined as duodenal papilla that had not been treated. Diagnostic ERCP was defined as cholangiography and/or pancreatography, bile cytology and/or pancreatic juice cytology, or intraductal ultrasonography. Therapeutic ERCP was defined as therapeutic interventions that did not include any form of diagnostic ERCP.

Serum pancreatic enzymes were considered elevated when the upper bounds of our institution’s reference values exceeded (s-Lip 55 U/L and s-Amy 132 U/L) and the following PEP diagnostic criteria were not met: (1) Acute episodes of abdominal pain and pressure pain on the upper abdomen; (2) Elevated levels of pancreatic enzymes in the blood or urine; and (3) Abnormal signs of acute pancreatitis by abdominal ultrasonography, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging. PEP was diagnosed when at least 2 of these 3 items were met and the presence of other pancreatic diseases or acute abdomen could be excluded[3]. For example, in elderly people, it is often difficult to evaluate the presence or absence of spontaneous pain due to the effects of analgesics used in ERCP. Thus, if hyperlipasemia or hyperamylasemia occurred after ERCP, an imaging test was added at the discretion of the attending physician. Therefore, even if the abdominal pain was mild, it was determined as PEP if pancreatitis was observed in the image findings. Up to 3 h post-ERCP was analyzed as the early stage after ERCP, and from 3 h post-ERCP to the next morning was analyzed as the late stage after ERCP. An early PEP diagnosis was defined as one made in the early stage after ERCP. Patients diagnosed with PEP in the early stage are not included among patients diagnosed with PEP in the late stage after ERCP. PEP severity was assessed using the grades of severity according to the revised Atlanta criteria[2].

ROC curves were constructed to establish relationships between sensitivity and specificity. ROC analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS Base 17.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Analysis of s-Lip and s-Amy AUCs and cutoff values based on the presence or absence of PEP was performed using SPSS Base 17.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). The DeLong test was used to perform head-to-head comparison between s-Lip and s-Amy for diagnosing PEP. Cutoff values were the closest point from the upper left of the ROC curves. Continuous data were given as the median and range. Categorical data were shown as number and percentages. P values < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

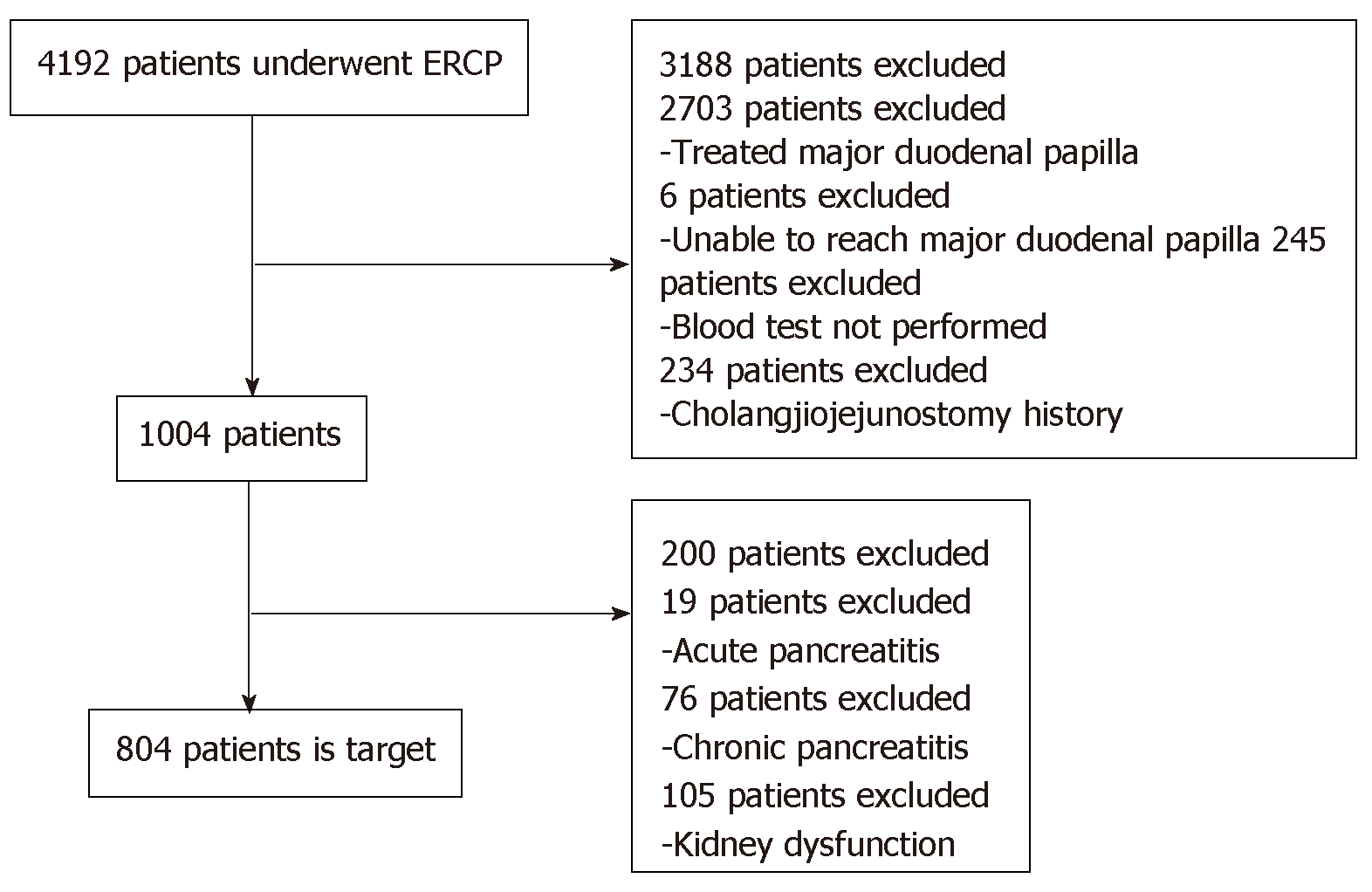

Based on the eligibility and exclusion criteria, 804 cases were registered (Figure 1). The patients’ median age was 71 years (range, 6-98 years) (male, 496, 61.7%); 31 (3.9%) had a history of pancreatitis, 6 (0.75%) had a history of PEP, 3 (0.4%) displayed sphincter Oddi dysfunction, 412 (51.2%) had benign disease, 303 (37.7%) underwent diagnostic ERCP, 202 (25.1%) had hyperlipasemia before ERCP, and 97 (12.1%) had hyperamylasemia before ERCP (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Value median [range] or n (%) |

| Age, yr | 71 [6-98] |

| Sex | |

| Male | 496 (61.7) |

| Female | 308 (38.3) |

| History of previous pancreatitis | |

| Yes | 31 (3.9) |

| No | 773 (96.1) |

| History of previous PEP | |

| Yes | 6 (0.7) |

| No | 798 (99.3) |

| Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction | |

| Yes | 3 (0.4) |

| No | 801 (99.6) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Benign | 412 (51.2) |

| Malignancy | 392 (48.8) |

| Indications for ERCP | |

| Diagnostic | 303 (37.7) |

| Therapeutic | 501 (62.3) |

| Hyperlipasemia before ERCP | |

| Yes | 202 (25.1) |

| No | 602 (74.9) |

| Hyperamylasemia before ERCP | |

| Yes | 97 (12.1) |

| No | 707 (87.9) |

Of the patients with serum pancreatic enzyme levels greater than 3 times the institutional upper bound after ERCP, in the early stage after ERCP, 236 patients (29.4%) exhibited hyperlipasemia and 104 patients (12.9%) exhibited hyperamylasemia. In the late stage after ERCP, 239 patients (29.7%) exhibited hyperlipasemia and 138 patients (17.2%) exhibited hyperamylasemia. Over the entire course, PEP occurred in 78 patients (9.7%). It occurred in the early stage after ERCP in 40 patients (51.3%) and in the late stage after ERCP in 38 patients (48.7%) (Table 2). Based on the grades of severity by the revised Atlanta criteria[2], there were 72 mild PEP cases (9.0%), 5 moderate cases (0.6%), and 1 severe case (0.1%) (Table 3).

| Value | |

| PEP | 78 (9.7) |

| Mild | 72 (9.0) |

| Moderate | 5 (0.6) |

| Severe | 1 (0.1) |

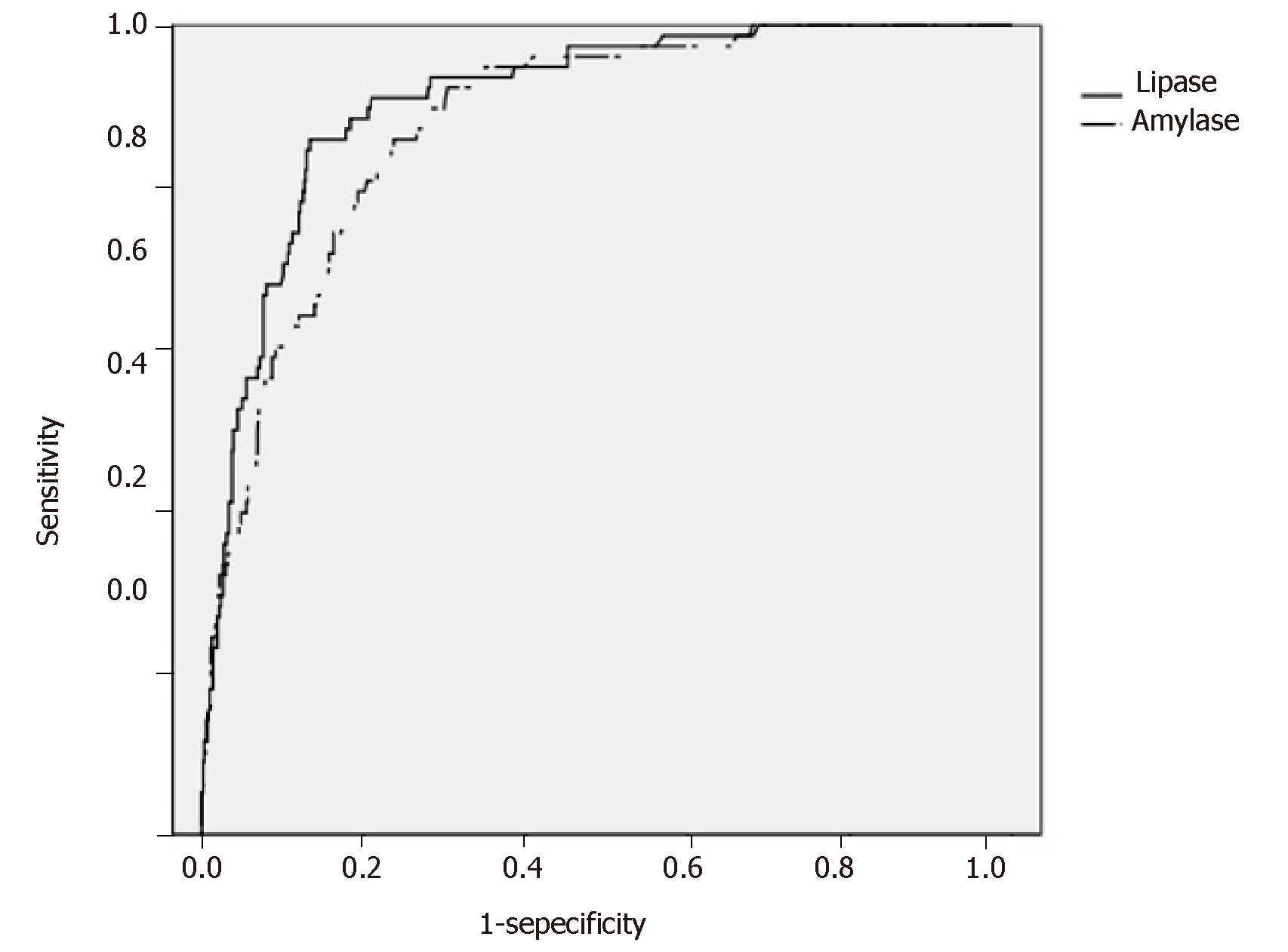

Figure 2 shows the ROC curves for s-Lip and s-Amy based on the presence or absence of PEP onset in the early stage after ERCP. The AUCs were 0.908 for s-Lip [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.880-0.940, P < 0.001] and 0.880 for s-Amy (95%CI: 0.846-0.915, P < 0.001), indicating both are useful for early diagnosis. By comparing the AUCs, s-Lip was found to be significantly more useful for the early diagnosis of PEP than s-Amy (P = 0.023) (Table 4). The optimal cutoff values calculated from the ROC curves were 342 U/L for s-Lip (sensitivity, 0.859; specificity, 0.867; PPV, 0.405; NPV, 0.981) and 171 U/L for s-Amy (sensitivity, 0.859; specificity, 0.763; PPV, 0.277; NPV, 0.979).

| s-Lip | s-Amy | P-value1 | |

| AUC (95%CI) | 0.908 (0.880-0.940) | 0.880 (0.846-0.915) | 0.023 |

| Optimal cutoff value (U/L) | 342 | 171 | ― |

| Sensitivity | 0.859 | 0.859 | ― |

| Specificity | 0.867 | 0.763 | ― |

| Positive predictive value | 0.405 | 0.277 | ― |

| Negative predictive value | 0.981 | 0.979 | ― |

The objective of this study was to examine the usefulness of s-Lip for the early diagnosis of PEP, including a comparison with s-Amy. Our study indicated that s-Lip might be preferable for the early diagnosis of PEP (ROC analysis, P = 0.023).

ERCP is now an important examination method in the diagnosis and treatment of pancreaticobiliary diseases. Therefore, although it is important to develop methods for preventing PEP, it is also necessary to discover other indicators so that when PEP cannot be avoided, it can be diagnosed and treated early. As with acute pancreatitis, if PEP is diagnosed early, therapy appropriate for the patient’s condition can be initiated early. Previous research on PEP has found that 37% of post-ERCP cases without abdominal pain but with hyperlipasemia (≥ 3 times normal upper bound) presented with PEP by CT[17] and that 30% of PEP cases diagnosed using image findings had pancreatic enzyme levels ≤ 3 times the normal upper bound[18]. However, most of these and other studies examined s-Amy levels[19-21]. S-Lip is superior to s-Amy in diagnosing acute pancreatitis, and if it could be shown to be similarly useful for the early diagnosis of PEP, more cases of PEP could be diagnosed early and receive treatment. The AUCs of s-Lip and s-Amy based on the presence or absence of PEP in the early stage after ERCP demonstrated the usefulness of both enzymes. Moreover, the optimal cutoff values based on the ROC curves had high sensitivity and specificity, indicating that both have high diagnostic power. The AUC of s-Lip was significantly larger, showing that s-Lip has a significantly greater diagnostic power than s-Amy for the early diagnosis of PEP. When these optimal cutoff values are used, the sensitivity of s-Lip resembles that of s-Amy. Although s-Lip and s-Amy are similarly useful for early screening tests for PEP, s-Lip had a higher specificity than s-Amy. S-Lip has a higher pancreatic specificity, and is known to be more useful than s-Amy in acute pancreatitis[12,13,22,23]. S-Lip might be more useful than s-Amy for PEP, similar to acute pancreatitis. Moreover, s-Lip had a higher PPV and NPV than s-Amy. A high PPV is an advantage in the diagnosis of PEP due to the low prevalence and high fatality associated with the condition; in such cases, early diagnosis and therapeutic intervention are more important. When the s-Lip cutoff value is exceeded, it is meaningful to actively perform a contrast CT examination. Based on these results, we believe that using s-Lip, with its higher specificity and PPV, would lead to more cases of PEP being diagnosed early and receiving treatment. In fact, of the 38 patients in the present study diagnosed with PEP in the late stage after ERCP, 32 patients (84.2%) had s-Lip levels higher than our cutoff value in the early stage after ERCP. In contrast, of the 38 patients in the present study diagnosed with PEP in the late stage after ERCP, 30 patients (78.9%) had s-Amy levels higher than our cutoff value in the early stage after ERCP. Sedatives and analgesics are often administered when ERCP is performed, which can make it difficult to assess abdominal pain in the early stage after ERCP. At this stage, none of these 32 cases exhibited abdominal pain, and none of them underwent CT, abdominal ultrasonography, or other imaging examinations. If imaging had been performed to examine these cases in more detail, PEP might have been diagnosed earlier and therapeutic interventions provided in some cases. In the future, when our s-Lip cutoff value is exceeded, we will carry out an image examination even when abdominal pain is unclear, as it may be possible to diagnose PEP earlier and to perform therapeutic intervention.

This study had several limitations, the most important of which was that it was performed at two centers as a retrospective study. Moreover, too many cases were excluded according to the exclusion criteria. Therefore, the usefulness of s-Lip needs to be reexamined by prospectively registering naïve major duodenal papilla cases as part of a multicenter study. Additionally, ERCP at a high-volume center is performed on more complicated cases than at other institutions. These include patients in whom cannulation of the bile duct or pancreatic duct is difficult, such as elderly patients with underlying diseases, patients who have undergone postoperative reconstruction using a balloon enteroscope, and patients with malignant disease. Thus, there could be slight differences between populations. A multicenter study is needed to resolve this limitation.

In this study, s-Lip was more useful than s-Amy for the early diagnosis of PEP (P = 0.023). Using the s-Lip cutoff value calculated in this study could help to diagnose PEP earlier, so that therapeutic interventions could be provided earlier.

Serum lipase (s-Lip) is considered the most useful pancreatic enzyme for diagnosing acute pancreatitis, and s-Lip is known to have greater diagnostic power than serum amylase (s-Amy). However, its usefulness for diagnosing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) has not been sufficiently investigated.

PEP is sometimes fatal. As such, PEP should be diagnosed early so that therapeutic interventions can be carried out. It is necessary to evaluate pancreatic enzymes that are useful for the early diagnosis of PEP.

This study aimed to retrospectively examine the usefulness of s-Lip for the early diagnosis of PEP.

We retrospectively examined 4192 patients who underwent ERCP at our two hospitals over the last 5 years. The primary outcomes were a comparison of the areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (AUCs) of s-Lip and serum amylase (s-Amy), s-Lip and s-Amy cutoff values based on the presence or absence of PEP in the early stage after ERCP via ROC curves, and the diagnostic properties of these cutoff values for PEP diagnosis.

In total, 804 cases were registered. The AUCs were 0.908 for s-Lip [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.880-0.940, P < 0.001] and 0.880 for s-Amy (95%CI: 0.846-0.915, P < 0.001), indicating both are useful for early diagnosis. By comparing the AUCs, s-Lip was found to be significantly more useful for the early diagnosis of PEP than s-Amy (P = 0.023).

S-Lip was significantly more useful for the early diagnosis of PEP. Measuring s-Lip after ERCP could help diagnose PEP early; hence, therapeutic interventions can be provided early.

Measuring s-Lip is a useful option for the early diagnosis of PEP. However, this study was limited as a retrospective at two centers. The usefulness of s-Lip needs to be reexamined by prospectively registering cases as part of a multicenter study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Smith RC, Leerhøy B S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhou BX

| 1. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1934] [Article Influence: 58.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4134] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3699] [Article Influence: 336.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (38)] |

| 3. | Yokoe M, Takada T, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Isaji S, Wada K, Itoi T, Sata N, Gabata T, Igarashi H, Kataoka K, Hirota M, Kadoya M, Kitamura N, Kimura Y, Kiriyama S, Shirai K, Hattori T, Takeda K, Takeyama Y, Hirota M, Sekimoto M, Shikata S, Arata S, Hirata K. Japanese guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: Japanese Guidelines 2015. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:405-432. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 256] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mine T, Morizane T, Kawaguchi Y, Akashi R, Hanada K, Ito T, Kanno A, Kida M, Miyagawa H, Yamaguchi T, Mayumi T, Takeyama Y, Shimosegawa T. Clinical practice guideline for post-ERCP pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:1013-1022. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dumonceau JM, Andriulli A, Elmunzer BJ, Mariani A, Meister T, Deviere J, Marek T, Baron TH, Hassan C, Testoni PA, Kapral C; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - updated June 2014. Endoscopy. 2014;46:799-815. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 362] [Article Influence: 36.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Smeets X, Bouhouch N, Buxbaum J, Zhang H, Cho J, Verdonk RC, Römkens T, Venneman NG, Kats I, Vrolijk JM, Hemmink G, Otten A, Tan A, Elmunzer BJ, Cotton PB, Drenth J, van Geenen E. The revised Atlanta criteria more accurately reflect severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis compared to the consensus criteria. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:557-564. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Napolitano G, Niro G, Valvano MR, Spirito F, Pilotto A, Forlano R. Incidence rates of post-ERCP complications: a systematic survey of prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1781-1788. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 669] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 695] [Article Influence: 40.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Freeman ML, Guda NM. Prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a comprehensive review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:845-864. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 305] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Leerhøy B, Elmunzer BJ. How to Avoid Post-Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2018;28:439-454. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vissers RJ, Abu-Laban RB, McHugh DF. Amylase and lipase in the emergency department evaluation of acute pancreatitis. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:1027-1037. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Agarwal N, Pitchumoni CS, Sivaprasad AV. Evaluating tests for acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:356-366. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Nordestgaard AG, Wilson SE, Williams RA. Correlation of serum amylase levels with pancreatic pathology and pancreatitis etiology. Pancreas. 1988;3:159-161. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Smith RC, Southwell-Keely J, Chesher D. Should serum pancreatic lipase replace serum amylase as a biomarker of acute pancreatitis? ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:399-404. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Orebaugh SL. Normal amylase levels in the presentation of acute pancreatitis. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12:21-24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Panteghini M, Pagani F, Alebardi O, Lancini G, Cestari R. Time course of changes in pancreatic enzymes, isoenzymes and, isoforms in serum after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Clin Chem. 1991;37:1602-1605. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Doppl WE, Weber HP, Temme H, Klör HU, Federlin K. Evaluation of ERCP- and endoscopic sphincterotomy-induced pancreatic damage: a prospective study on the time course and the significance of serum levels of pancreatic secretory enzymes. Eur J Med Res. 1996;1:303-311. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Uchino R, Sasahira N, Isayama H, Tsujino T, Hirano K, Yagioka H, Hamada T, Takahara N, Miyabayashi K, Mizuno S, Mohri D, Sasaki T, Kogure H, Yamamoto N, Nakai Y, Tada M, Koike K. Detection of painless pancreatitis by computed tomography in patients with post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography hyperamylasemia. Pancreatology. 2014;14:17-20. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Artifon EL, Chu A, Freeman M, Sakai P, Usmani A, Kumar A. A comparison of the consensus and clinical definitions of pancreatitis with a proposal to redefine post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2010;39:530-535. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Obana T. Relationship between post-ERCP pancreatitis and the change of serum amylase level after the procedure. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3855-3860. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang P, Li ZS, Liu F, Ren X, Lu NH, Fan ZN, Huang Q, Zhang X, He LP, Sun WS, Zhao Q, Shi RH, Tian ZB, Li YQ, Li W, Zhi FC. Risk factors for ERCP-related complications: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:31-40. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 294] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Lukić S, Alempijević T, Jovanović I, Popović D, Krstić M, Ugljesić M. Occurrence and risk factor for development of pancreatitis and asymptomatic hyperamylasemia following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography--our experiences. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2008;55:17-24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Treacy J, Williams A, Bais R, Willson K, Worthley C, Reece J, Bessell J, Thomas D. Evaluation of amylase and lipase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71:577-582. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 69] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Keim V, Teich N, Fiedler F, Hartig W, Thiele G, Mössner J. A comparison of lipase and amylase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in patients with abdominal pain. Pancreas. 1998;16:45-49. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |