Published online May 8, 2016. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i13.573

Peer-review started: June 19, 2015

First decision: August 10, 2015

Revised: April 1, 2016

Accepted: April 14, 2016

Article in press: April 18, 2016

Published online: May 8, 2016

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of liver cancer. The main risk factors for HCC are alcoholism, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, obesity, type 2 diabetes, cirrhosis, aflatoxin, hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease and hemophilia. Occupational exposure to chemicals is another risk factor for HCC. Often the relationship between occupational risk and HCC is unclear and the reports are fragmented and inconsistent. This review aims to summarize the current knowledge regarding the association of infective and non-infective occupational risk exposure and HCC in order to encourage further research and draw attention to this global occupational public health problem.

Core tip: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common human cancer. This review summarizes current knowledge regarding the occupational risk factors of HCC. In particular, we underline not only the infective but also non-infective occupational risk exposure, including chemical agents and toxic metabolites which are a major cause of liver damage.

- Citation: Rapisarda V, Loreto C, Malaguarnera M, Ardiri A, Proiti M, Rigano G, Frazzetto E, Ruggeri MI, Malaguarnera G, Bertino N, Malaguarnera M, Catania VE, Di Carlo I, Toro A, Bertino E, Mangano D, Bertino G. Hepatocellular carcinoma and the risk of occupational exposure. World J Hepatol 2016; 8(13): 573-590

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v8/i13/573.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v8.i13.573

The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is increasing worldwide. There are geographical areas with a high prevalence, as in Asia and Africa, and death from HCC has increased in the United States and Europe[1-5].

Aflatoxin[6], alcohol intake[7], hepatitis B virus (HBV)[4], hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection[5] and oral contra-ception[8,9] are known risk factors for HCC, whereas cigarette smoke, anabolic steroids and insulin resistance are suspected to be contributing factors[10-16].

The relationship between occupational risk and HCC is often unclear and the reports are fragmented and inconsistent[17-19]; however, it is very commonly reported that vinyl chloride monomer (VCM) induced angiosar-coma of the liver[20].

HCC mortality, assessed by standardized mortality ratio, has been reported in different categories of workers: Building and chemical workers, painters, sub-jects exposed to solvents and workers in the textile industry have often been reported to be at high risk for HCC[21-30]. However, such studies have often failed to identify a single agent responsible for the heightened HCC risk. There have been few investigations of occupational exposure and liver cancer. A number of factors and confounders have precluded drawing firm conclusions[31].

The possible associations between the risk of infection and non-infectious occupational hazards and HCC will be discussed, in the hope of drawing attention to this global public health problem.

The PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science databases were searched using the following keywords: “HCC”, “occupational exposure”, “chemical agents”, “arsenic”, “cadmium”, “HBV”, ”HCV”, “molecular hepatocarcinoge-nesis”, “molecular immunological targets”, “autophagy”, “mitophagy” and “epigenetic events”. Published data at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) were consulted.

Infection is one of the main contributors to cancer develop-ment[32]. There are 11 biological agents classified as IARC group 1 carcinogens[33,34]. HBV, HCV and AFB1 are responsible for HCC development[35]. The vast majority of the global cancer burden attributable to infection occurs in less developed regions (Table 1).

| Risk agent | CAS No. | Occupational exposure | IARC class |

| Infective risk | |||

| HBV | - | Health care workers[4,38,41,44], waste operators[38,44] | Group 1[34] |

| HCV | - | Health care workers[38,39,61] | Group 1[34] |

| Aflatoxin B1 | 1162-65-8 | Paper mill and sugar factory; poultry production; rice mill; waste management; swine industry; agri-food industry; wheat handling; textile manufacturing[77,78,87-91,93,96] | Group 1[76] |

Infection with HBV and HCV can be through parenteral or unapparent transmission[36-42].

The risk of hepatitis from needlestick injury from an hepatitis B envelope antigen positive (HBeAg+) source is 22%-31%, whereas the risk of contracting clinical hepatitis from a needlestick injury involving an hepatitis B surface antigen positive (HBsAg+), eAg- source is 1%-6%. Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), including HBIG and the HBV vaccine, is believed to be 85%-95% effective. HBV vaccine or HBIG alone is thought to be 70%-75% effective[43-45].

The risk of HCV transmission from percutaneous expo-sure is approximately 2%. HCV is rarely transmitted from mucous membrane exposure to blood (both docu-mented cases have been when the source patient was human immunodeficiency virus/HCV co-infected) and it has never been documented following blood exposure to intact or non-intact skin. There is no known PEP for HCV exposure. According to a European case-control study, assessment of the risk of transmission after occupational HCV exposure should take into account the injury severity, device involved and the HCV RNA status of the source patient[46-50].

Chronic HBV infection has a causal role in HCC develop-ment[36] since it promotes carcinogenesis through liver injury (necrosis and inflammation) and cirrhosis develop-ment (fibrosis and regeneration)[41,43-45]. More-over, HBV and HCV co-infection causes a higher than 50-fold risk compared to HCC[51-54].

Risk factors for liver cancer in HBV patients include: (1) host-related risk factors: Older age, Asian ethnicity, male sex, alcohol intake and advanced liver disease[55-57]; (2) viral risk factors: HBV genotype C, mutations of pre-S, enhancer-H, core promoter, HCV or hepatitis Delta virus infection and PC/BCP HBV variants[45,58]; and (3) risk factors related to host-virus interaction: Cirrhosis, high HBV-DNA serum levels, prolonged HBeAg positivity, prolonged HBsAg positivity and high HBsAg serum levels[59-62].

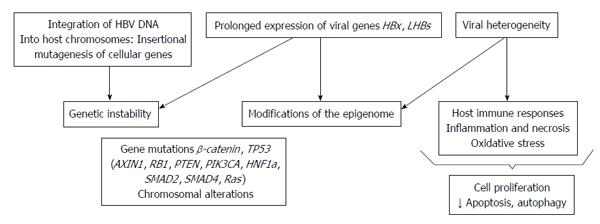

Lastly, the HCC risk factors in chronic HBV infection are different and the pathogenesis is characterized by the combined action of different alterations involving genetic, epigenetic and immunological factors[63-71] (Figure 1).

The mechanism by which HCV causes HCC is not wholly clear. It has been suggested that HCV proteins have direct oncogenic properties[5]. Chronic HCV infection leads to cirrhosis in 10%-20% of patients of whom 1%-5% develop liver cancer[5]. Central tumor suppressor genes and a number of proto-oncogenes, such as retinoblastoma tumor suppressor (Rb) and P53, have been suggested as targets of direct alteration by HCV proteins; the wnt/β-catenin and transforming growth factor-β pathways may also be directly affected[5].

Moreover, chronic infection, necrosis and cell re-generation, fibrosis and cirrhosis are, together with the direct mechanisms, the high risk factors for HCC. Finally, HBV or HCV chronic infection has immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive effects[71-73].

The aflatoxins are metabolic products of certain fungi, Aspergillus flavus and parasiticus that develop in cereals (maize), oilseeds (groundnuts) and dried fruit and are chemicals of the furanocoumarins type. To date, we have isolated 17 aflatoxins and 5 are relevant to dissemination and toxicity. High exposure concentrations cause acute hepatitis. Chronic exposure causes the development of liver cancer. This could be caused by the aflatoxin ability to determine the mutation of the p53 tumor suppressor gene, which in normal conditions induces the apoptosis processes[74-77].

The risk of HCC increases when the exposure occurs in the presence of HBV infection, as occurs in the Chinese population[78-96].

A wide range of occupational activities may involve worker exposure to a variety of chemical agents. The liver is the main organ involved in metabolism and in toxicokinetics of a xenobiotic. However, it is frequently also a target organ because of its blood supply and the many metabolic and excretory processes in which it has a role. Adverse effects of chemical exposure involv-ing the liver (hepatotoxicity) comprise hepatocellular damage, cholestatic injury, fatty liver, granulomatous disease, cirrhosis and malignancies, including HCC. A variety of chemicals comprising VCM, organic solvents, chlorinated pesticides and arsenic exert adverse effects on the liver[97] (Tables 2 and 3).

| Risk agent | CAS No. | Occupational exposure | IARC class |

| Non-infective risk | |||

| VCM | 75-01-4 | Plastics, plumbing, cabling, house framing, waterproof clothing, medical devices and food packaging industry[98,99,102,103,105-108,111,112,114-120] | Group 1[76] |

| TCE | 79-01-6 | Dry cleaning; paint stripping; metal degreasing; production of chlorinated chemical compounds; shoe manufacturing; aircraft/aerospace, electronics and printing industry[125,127] | Group 1[129] |

| PCE | 127-18-4 | Dry cleaning; textile processing; metal degreasing[138] | Group 2A[129] |

| DDT | 50-29-3 | Farming industry[141,145] | Group 2B[148] |

| N-nitrosamines | 35576-91-1 | Plastic, rubber and pharmacological manufacturing; farming industry; metalworking; electrical component production and use; gasoline and lubricant additives, production and use[159-165] | Group[160,161] |

| TCDD | 1746-01-6 | Waste management; paper mill; timber manufacturing; iron and steel manufacturing; electric power industry[175,179] | Group 1[76] |

| PeCDF | 57117-31-4 | Cement and metalworking industry; chemical manufacturing[171,172,175] | Group 1[76] |

| PCB | 1336-36-3 | Electrical industry, plastic and chemical industry; maintenance/repair technicians of PCB devices[175,186-190] | 1Group[76,207] |

| PBB | Electronics recycling industry; maintenance/repair technicians of PBB devices[209-212] | Group 2A[207] | |

| Chloral | 75-87-6 | Insecticides and herbicide production; polyurethane foam production and use[125,214,215] | Group 2A[216] |

| Chloral hydrate | 302-17-0 | Pharmaceutical producing; health care workers; laboratory research; water disinfection by chlorination[129,216] | Group 2A[216] |

| O-toluidine | 95-53-4 | Dye production and use; herbicide and pharmaceutical production; rubber industry; clinical laboratories[220-222,227,228] | Group 1[76] |

| MOCA | 101-14-4 | Rubber and polyurethane industry[220,230-232] | Group 1[76] |

| 4-ABP | 92-67-1 | Rubber industry; dyes production[220,235-238] | Group 1[76] |

| BZD and dyes metabolized to BZD | 92-87-5 | Dye production and use; clinical laboratories[220,247] | Group 1[76] |

| Risk agent | CAS No. | Occupational exposure | IARC class |

| Non-infective risk | |||

| As | 7440-38-2 | Timber manufacturing; pesticide use; As extraction industry; lead processing; pharmaceutical industry; glass industry; leather preservatives; antifouling paints; agrochemical production; microelectronics and optical industries; non-ferrous metal smelters; coal-fired power plants[254-258] | Group 1[263] |

| Cd | 7440-43-9 | Cd mining; manufacturing of Cd-containing ores and products; Ni-Cd battery manufacturing, Cd alloy production[275,277,278] | Group 1[263] |

VCM, chemical abstract service number (CAS No. 75-01-4), is a chlorinated organic compound. VMC is found in cigarette smoke and is mainly used in the production of polymer polyvinyl chloride (PVC). VCM is rapidly absorbed after inhalation and is primarily metabolized by the liver.

Since PVC is harmless in its polymeric form, workers handling the finished goods are not at risk of exposure. The risk phases are those in which the workers are in contact with the material when still in the monomeric state. Many epidemiological studies have demonstrated the high prevalence of exposure to VCM in those working with the chemical. Thiodiglycolic acid is the main VCM metabolite detected in the urine of occupationally exposed subjects.

It has been shown in both human and animal models that VCM is able to induce liver angiosarcoma and HCC[98-104].

Maroni et al[105] reported the hepatotoxicity of VCM and other studies have shown the capacity of VCM to induce specific gene mutations in the liver[105-117].

Various European and Italian studies have reported the apparent association between the amount and timing of exposure to VCM and development of HCC in those exposed[118-120].

Organic solvents are substances that contain carbon and are capable of dissolving or dispersing one or more other substances. Millions of workers are exposed to organic solvents contained in products such as varni-shes, adhesives, glues, plastics, textiles, printing inks, agricultural products and pharmaceuticals.

Many organic solvents are recognized by NIOSH as carcinogens (carbon tetrachloride, benzene and trichloroethylene), reproductive hazards and neurotoxins. Among the organic solvents, trichlorethylene (TCE) and perchlorethylene (PCE) have been reported to be capable of promoting cancer in humans[121,122].

TCE (CAS 06/01/79) has been associated with a high prevalence of liver tumors in exposed workers. Although the hepatic metabolism of this solvent is known, the molecular alterations that cause liver cancer are not completely known[123-127].

It is hypothesized that TCE may be involved in various mechanisms, such as the reduction of pro-grammed cell apoptosis and the uncontrolled prolife-ration induced by peroxisome activated receptor (PPAR). In fact, it has been proved that TCE is able to bind PPAR[128-132].

RAD51 is a eukaryote gene. The protein encoded by this gene is a member of the RAD51 protein family which assists in the repair of DNA. TCE binds the RAD51, consequently alters the DNA repair and can cause a certain degree of genomic instability.

Finally, it was reported that TCE can cause hypome-thylation of DNA and hyperexpression of oncogenes (e.g., MYC and JUG), responsible for uncontrolled cell proliferation[133-137].

A high prevalence of liver cancer was found in animal models exposed to PCE (CAS 127-18-4)[138,139].

Porru et al[140] showed that, in workers chronically exposed to organic solvents (toluene and xylene), there is an increased risk of HCC and that the risk is time-dependent.

Pesticides are widely used in agriculture to get the best quality products and appearance. Farmers and many workers in the agro-food chain are exposed to these substances as well as consumers who eat agri-cultural products that are not properly cleaned and decontaminated.

Among these substances, 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis (p-chlorophenyl)-ethane (DDT) and its metabolite 1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis (p-chlorophenyl)-ethylene (DDE) have been extensively studied. DDT was used both in agriculture and for environmental disinfection until its use was later forbidden in both America and Europe because of its toxic effects on humans. However, in Africa and many parts of Asia it is currently used to control diseases delivered by an insect as a vector (e.g., Leishmaniasis, malaria).

In humans, DDT contamination occurs through con-tact with the skin, mucous membranes and inha-lation. After DDT absorption, it is distributed to all organs and a portion will be stored in fatty tissues, especially if the exposure was massive[141-146].

Many insecticides, including DDT, were reported to be responsible for leading the development of HCC[147-152]. This occurs through different mechanisms not yet completely understood. Moreover, DDT has an estrogenic effect, while DDE has anti-androgenic effects. DDT may also interfere with the CYP3A1 gene involved in the inflammatory and immune responses in the liver. Probably none of these mechanisms is individually able to result in HCC but the simultaneous presence of these alterations may lead to the development of liver cancer. Furthermore, the presence of important cofactors, such as HBV, HCV and AFB1, amplifies the risk in exposed populations[152-158].

Nitrosamines are carcinogenic chemical compounds produced when nitrite, a preservative added to certain foods (fish, fish byproducts, certain types of meat, cheese products, beer), combines with amino acids in the stomach. Nitrosamines can be also found in latex products and tobacco smoke. Moreover, nitrosamines are produced in research laboratories, in rubber and tyre manufacturing processes and may be found as conta-minants in the final rubber product. Some nitrosamines have been found to be effective for a variety of purposes, including antimicrobial (No. 11) or chemotherapeutic agents (Nos. 5 and 9) in conjunction with others, herbicides (Nos. 5 and 6), additives to soluble and synthetic metalworking fluids (No. 3), solvents or gasoline and lubricant additives (No. 4), antioxidants, stabilizers in plastics, fiber industry solvents and copolymer softeners, and to increase dielectric constants in condensers. Contamination can occur with skin contact and by ingestion and/or inhalation.

Nitrosamines are carcinogenic and are implicated in nasopharyngeal, esophageal, stomach, liver and urinary bladder cancers[159].

From 1981 to 1991, the United States - National Toxicology Program conducted several investigations to characterize and assess the toxicological potential and carcinogenic activity of N-nitrosamines in laboratory animals (rats and mice). The results were reported in the second (1981) (N-nitrosamines: 2-7, 9-15) and sixth (1991) (N-nitrosamines: 1-8) annual report on carcinogens[159-163].

In environmental surveys of some European rubber factories, de Vocht et al[164] found the average N-nitro-samine levels well below the regulatory limits in force but high accidental exposures have still occurred. In fact, they detected high levels of urinary N-nitrosamines in exposed workers[162,164-166]. Recent studies have reported a correlation between exposure to N-nitrosamines and HCC which might be due to the shortening of telomeres among workers in the rubber industry. Telomeres are critical to main-taining the integrity of chromosomes and telomere length abnormalities are associated with carcinogene-sis[163,165,167-169].

The dioxins and dioxin-like compounds are a class of heterocyclic organic compounds whose molecular structure fundamentally consists of a ring of six atoms, four carbon and two oxygen atoms; dioxin in the strict sense is differently stable and comes in two different positional isomers. Commonly referred to dioxins are also compounds derived from furan, in particular diben-zofurans. Therefore, part of the dioxin-like compounds are polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychlori-nated dibenzofurans and among them, the most toxic is 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). It has been shown that compounds of the family of dioxins are formed during the initial stage of the waste combustion when combustion generates gaseous HCl in the presence of catalysts, such as copper and iron. Organic chlor-ine, which is bound to organic compounds of polymers such as PVC, is mainly responsible for the formation of compounds belonging to the family of dioxins. Dioxins are generated even in the absence of combustion, for example in bleaching paper and tissues with chlorine.

About 90% of human dioxin, except for cases of exposure to specific sources such as industrial plants and incinerators, takes place through food (in particular the fat of animals exposed to dioxin) and not directly by air. The phenomenon of bioaccumulation is very important, i.e., the possibility that dioxin enters into the human food chain from plants, through herbivores, carnivores and finally humans[170-176]. Dioxins are classi-fied as definitely carcinogenic and are in the IARC group 1 carcinogenics for humans.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has classified TCDD as an occupatio-nal carcinogen that can cause space-occupying liver lesions, both non-neoplastic and neoplastic, such as in HCC[177-181].

Many studies have indicated that the carcinogenic capacity of TCDD may be due to the interaction between TCDD and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). This receptor is implicated in several xenobiotic metabolisms but there is evidence that AhR is able to control other genes, some of which have a pro-oncogenic capa-city[182-184]. The TCDD is an important AhR agonist and is therefore able to induce and enhance HCC development and diffusion[184].

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) are synthetic chlo-rinated aromatic hydrocarbons, chemically stable and therefore persistent environmental contaminants. The contamination occurs by skin contact or inhalation, which also allows the possibility of developing vapors for equip-ment containing PCB overheating[185].

Studies in animal models have shown that these chemical compounds can cause chronic hepatitis as well as cancers, such as HCC and cholangiocarcinoma, especially if there is high exposure and a prolonged time. However, there is little data on liver injury in humans. In one case, exposure to olive oil accidentally contaminated with PCB resulted in death from hepatic cirrhosis. Other studies in workers exposed to the PCB have reported an increased incidence of liver tumors[185-188].

Some possible mechanisms by which PCB can cause cancer have been assumed: Reactive oxygen species (ROS) is produced through the enzymatic oxidation or autoxidation of PCB; PCB determines the increased expression of genes responsible for inflammation and apoptosis in the liver; and PCB has “toxic” effects on certain genes, such as the loss of part of a chromosome and chromosome breakage[189-199]. ROS are also able to reduce telomerase activity which can determine telomere shortening. The contribution of all or part of these alterations may facilitate the onset of tumors and more specifically HCC[200-205]. At present we have no conclusive data on the relationship between PCBs and HCC and further studies will be needed to establish the causal link. However, the evidence reported by animal model studies have made it possible to classify PCB in IARC group 1[206,207].

Polybrominated biphenyls are polyhalogenated deri-vatives of a biphenyl core[208] that are chemically stable and therefore persistent environmental contaminants. Whereas they were widely used just a few years ago, they are now subject to restrictive rules that limit their use in the European Union (Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive).

Contamination can occur through skin contact, in-halation and ingestion[209-212]. Based on data obtained from animal research, PDDs are considered potential human carcinogens and can result in hematological, digestive system and liver malignancies. The pathogenic mechanisms by which they can result in PDD cancer are similar to those described for PCB which allows them to be defined as “probably carcinogenic for humans” (group 2A)[207].

Chloral (or trichloroacetaldehyde) is a chemical com-pound with the formula C2HCl3O and CAS (chemical abstracts service) 75-87-6. Chloral is produced by the chlorination of ethanol and is also produced as an intermediate in the synthesis of various products, for example DDT. Chloral is used for production of chloral hydrate (formula C2H3Cl3O2 and CAS No. 302-17-0).

Chloral hydrate is an ingredient used in Hoyer’s solution[213-216]. In mouse studies, oral administration of chloral in water induced liver nodules as well as hyperplastic nodules and HCC after 92 wk. Significant increases in HCC incidence were seen in treated mice surviving 104 wk[217,218]. Some studies indicate that chloral hydrate is able to produce genomic alterations, such as chromosomal aberrations, loss of cell apoptosis and rupture of the gap junction. There are limited studies on carcinogenicity in humans. However, thanks to evidence in animal studies, chloral and chloral hydrate are currently classified in group A2[216-219].

Ortho-toluidine (O-toluidine) (CAS No. 95-53-4) is used in the chemical and rubber industry and is found in some colorants, herbicides and pesticides. O-toluidine can be an environmental contaminant if in the water used for irrigation of the cultivated fields. It has also been found in tobacco cigarettes. In animal models, O-toluidine caused bladder cancer and its exposure increased the incidence of HCC. Its carcinogenic power is probably due to the ability to determine the formation of DNA adducts, causing damage to the DNA structure. Therefore, O-toluidine is classified in group A[220-229].

4,4’-Methylene bis (2-chlorobenzylamine) (MOCA) (CAS No. 101-14-4), used in the rubber industry, can be absorbed through the skin in workers, while population exposure occurs by ingestion of vegetables grown in contaminated soil. The ingestion or subcutaneous injection of MOCA in rats results in an increased inci-dence of HCC and lung cancer[230-232]. MOCA has a documented detrimental effect on the genome; in fact, it is able to determine chromatin alterations and deletions[76,233]. MOCA is classified in IARC group 1.

4-aminobiphenyl (4-ABP) is used in the rubber industry as an antioxidant and a dye and is also found in ci-garettes. It is classified in IARC group 1[76]. In rats, 4-ABP ingestion causes bladder cancer, angiosarcoma and HCC; subcutaneous or intraperitoneal exposure determines a high incidence of HCC[234]. The metabolism of 4-ABP determines the formation of N-hydroxyl ABP which is a mutagen. 4-ABP can form a DNA adduct. In human liver tissue, higher 4-ABP-DNA levels were observed in HCC cases compared with controls[235-241]. Although there was a dose-related increase in 4-ABP DNA (cigarettes smoked/day) and an association with mutant p53 protein expression in bladder cancers, there are currently no reports of p53 or other specific gene mutations caused by exposure to PAH or 4-ABP in HCC[242-244].

In the past, benzidine (BZD) (CAS No. 92-87-5) and dyes metabolized to benzidine have been widely used in the production of dyes. Their use is currently banned in the United States and Europe. However, the use of products containing these substances may expose people to health risks[245-248]. Epidemiological data on the risk of tumors in humans are limited, but the ingestion of BZD in rats increases the incidence of HCC[249-252]. BZD and dyes metabolized to BZD are classified in group 1 carcinogens[76].

Arsenic (As) (CAS 7440-38-2) is widespread in nature and, combined with other elements, forms very toxic inorganic compounds that can pollute the water and contaminate the population. The workers in mechanical industries are exposed to the risk of illness from dyes, chemicals and glass[253-258].

After oral intake and gastrointestinal absorption, it is metabolized in the liver where it is conjugated with glutathione and methylated[259,260]. The chronic exposure to small amounts produces chronic liver disease, cirrho-sis and HCC.

In the 2004 IARC monograph, the result of inor-ganic As in HCC formation was called “limited”. In contrast, more recent data from animal models have shown the possibility of a strong bond with liver tumor formation[261-268].

Various carcinogenic mechanisms, genetic and epigenetic, have been proposed: DNA methylation, oxidative damage, genomic instability and reduction of programmed cell death[269-274].

Cadmium (Cd) (CAS No. 7440-43-9) is a chemical element used as an anti-corrosion coating and a pigment. It is combined with lithium in rechargeable batteries and is also in cigarette tobacco. In fact, a cigarette contains about 2.0 μg Cd, of which 10.2% is transferred to the smoke[275]. Cd in the blood and body of smokers are typically double those found in non-smokers[276]. Burning municipal waste leads to inhalation of Cd. Workers in the metal and plastic product industry and workers involved in the construction of solar panels are exposed to Cd[277,278].

In 2011, Cd production was estimated to be 600 metric tons in United States. Most of the Cd produced today is obtained from zinc and products recovered from spent Ni-Cd batteries. China, South Korea and Japan are the leading producers, followed by North America[278]. According to OSHA estimates, 300000 workers are exposed to Cd in the United States. Cd found in food and cigarette smoke accumulates in the liver, kidney and pancreas. Liver concentrations increase with age, peaking at 40-60 years.

Based on epidemiological data, the IARC states that there is no evidence of unequivocal carcinogenic effects of Cd[278-282].

However, many animal studies have demonstrated the ability of Cd to determine various tumors, including HCC. This risk is dose and time-dependent and it is conditioned on the exposure mode. Oxidative stress, DNA methylation, the failure of DNA repair, activation of oncogenes, uncontrolled cell growth and the loss of apoptosis are among the mechanisms hypothesized by researchers[283-286]. Interestingly, Sabolić et al[287] have shown that the Cd can be internalized in the Kupffer cells which begin to produce cytokines, some of these are indicated as cofactors in the development of HCC.

Some studies have reported that chronic exposure to Cd increases the risk of tumors in humans[288-290]. However, large epidemiological studies are necessary to demonstrate whether long term Cd contamination is responsible for HCC development in humans, as in animal models.

Workplace risk prevention and safety rely chiefly on eliminating the risk itself (primary prevention) and, when it is not technically feasible, measures have to be enacted to reduce risk to a minimum[291].

When chemical agents are involved, primary pre-vention entails replacing a toxic agent with a non-toxic one. However, some mutagenic/carcinogenic agents can be produced in synthetic processes as inter-mediates or waste products[292]. As regards biological agents, it is critical to distinguish deliberate introduction of an agent into the working cycle, as in research centers, from the potential exposure resulting from its unwanted presence, as in the case of health care workers. Whereas the biological agent can be replaced in the former case, other measures have to be enacted in the latter[293].

When risk assessment determines the existence of a healthy risk, adequate risk control systems have to be implemented. Such systems are divided into general and personal protection devices (PPD). The former include adoption of technical and procedural measures, for instance the reduction of environmental pollutants, whereas PPD largely consist of devices worn by workers (e.g., masks, gloves), preventing direct contact with vapors, fumes and/or potentially contaminated material, e.g., biological fluids[294]. Biological risk prevention may involve mandatory vaccine prophylaxis, as in the case of HBV infection. Moreover, the fast pace of advances in vaccine development and protection equipment and devices requires continuous re-assessment of workplace protection systems[295,296].

In workplaces where risks are documented, safety procedures must be instituted in accordance with national guidelines. In case of flaws or deficiencies in such guidelines, those in charge of workplace safety are required to refer to the guidelines of internationally recognized organizations such as the Centers for Dis-ease Control and Prevention, American Conference of Industrial Hygienists, NIOSH, etc.

The employer and occupational physician have key roles in preventing occupational risk and diseases. The occupational physician, besides carrying out bio-logical monitoring and health surveillance (secondary prevention), is responsible for promoting workplace health[291].

As regards HCC prevention, all exposed workers should have HBV vaccination. In addition, campaigns against smoking and alcohol drinking should be orga-nized, providing an explicit warning that these factors may contribute to the development of liver cancer[10-12,101].

Development and progression of HCC is still not a completely known multistage process. Genetic, epige-netic and immunological factors probably contribute to the development of HCC[7,11,13,37,38,50,51,101,297,298].

In conclusion, the precancerous milieu of chronic liver disease is characterized by neo-angiogenesis, inflammation with ROS production and fibrosis. Synch-ronous events occurring in this setting also include hypoxia, oxidative stress, apoptosis, mitophagy and autophagy[299-302].

Autophagy shows a double face in HCC. While autophagy helps to prevents tumorigenesis, it is also used by the cancer cells for survival against apoptosis by traditional chemotherapeutic drugs[303,304]. Initially, autophagy functions are as a tumor suppressor and later, when HCC has developed, the autophagy may contribute to its growth[303,305].

Microbes have evolved mechanisms to evade and exploit autophagy and both HBV and HCV use auto-phagy for their own survival[306]. Studies have shown that autophagy enhances viral replication at most steps of HBV replication and that autophagy proteins are likely to be factors for the initial steps of HCV replication[307,308]. In tumor cells with defects in apoptosis, autophagy allows prolonged survival.

All these mechanisms are still being studied in order to provide new therapeutic approaches to HCC[309]. Despite the progress achieved in understanding the cancer process and the impact of this knowledge on treatment, primary prevention remains the most effective approach to reduce cancer mortality in both developed and deve-loping countries for the near future[9,37,38,50,51,56,309].

P- Reviewer: Tomizawa M S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Biological agents. Volume 100 B. A review of human carcinogens. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100:1-441. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, London WT. Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: an emphasis on demographic and regional variability. Clin Liver Dis. 2015;19:223-238. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 572] [Article Influence: 63.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wallace MC, Preen D, Jeffrey GP, Adams LA. The evolving epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global perspective. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:765-779. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 263] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Papatheodoridis GV, Chan HL, Hansen BE, Janssen HL, Lam-pertico P. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B: assessment and modification with current antiviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2015;62:956-967. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 357] [Article Influence: 39.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lemon SM, McGivern DR. Is hepatitis C virus carcinogenic? Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1274-1278. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Saad-Hussein A, Taha MM, Beshir S, Shahy EM, Shaheen W, Elhamshary M. Carcinogenic effects of aflatoxin B1 among wheat handlers. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2014;20:215-219. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Askgaard G, Grønbæk M, Kjær MS, Tjønneland A, Tolstrup JS. Alcohol drinking pattern and risk of alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study. J Hepatol. 2015;62:1061-1067. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 149] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bassuk SS, Manson JE. Oral contraceptives and menopausal hormone therapy: relative and attributable risks of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other health outcomes. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25:193-200. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bertino G, Demma S, Ardiri A, Toro A, Calvagno Gs, Mala-guarnera G, Bertino N, Malaguarnera M, Malaguarnera M, Di Carlo I. Focal nodular hyperplasia from the surgery to the follow-up. Change of therapeutic approach. Acta Medica Mediterranea. 2014;30:1329-1336. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Lv Y, Liu C, Wei T, Zhang JF, Liu XM, Zhang XF. Cigarette smoking increases risk of early morbidity after hepatic resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:513-519. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Purohit V, Rapaka R, Kwon OS, Song BJ. Roles of alcohol and tobacco exposure in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Life Sci. 2013;92:3-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hsieh YH, Chang WS, Tsai CW, Tsai JP, Hsu CM, Jeng LB, Bau DT. DNA double-strand break repair gene XRCC7 genotypes were associated with hepatocellular carcinoma risk in Taiwanese males and alcohol drinkers. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:4101-4106. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Loomba R, Yang HI, Su J, Brenner D, Barrett-Connor E, Iloeje U, Chen CJ. Synergism between obesity and alcohol in increasing the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:333-342. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 136] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bertino G, Ardiri AM, Alì FT, Boemi PM, Cilio D, Di Prima P, Fisichella A, Ierna D, Neri S, Pulvirenti D. Obesity and related diseases: an epide-miologic study in eastern Sicily. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2006;52:379-385. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Hardt A, Stippel D, Odenthal M, Hölscher AH, Dienes HP, Drebber U. Development of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with anabolic androgenic steroid abuse in a young bodybuilder: a case report. Case Rep Pathol. 2012;2012:195607. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Toro A, Mahfouz AE, Ardiri A, Malaguarnera M, Malaguarnera G, Loria F, Bertino G, Di Carlo I. What is changing in indications and treatment of hepatic hemangiomas. A review. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13:327-339. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Vinci M, Malaguarnera L, Pistone G. RS3PE and ovarian cancer. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:429-431. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Czarnecki LA, Moberly AH, Turkel DJ, Rubinstein T, Pottackal J, Rosenthal MC, McCandlish EF, Buckley B, McGann JP. Functional rehabilitation of cadmium-induced neurotoxicity despite persistent peripheral pathophysiology in the olfactory system. Toxicol Sci. 2012;126:534-544. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yang CJ, Lin JL, Lin-Tan DT, Weng CH, Hsu CW, Lee SY, Lee SH, Chang CM, Lin WR, Yen TH. Spectrum of toxic hepatitis following intentional paraquat ingestion: analysis of 187 cases. Liver Int. 2012;32:1400-1406. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sherman M. Vinyl chloride and the liver. J Hepatol. 2009;51:1074-1081. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wong O, Morgan RW, Kheifets L, Larson SR, Whorton MD. Mortality among members of a heavy construction equipment operators union with potential exposure to diesel exhaust emissions. Br J Ind Med. 1985;42:435-448. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jansson C, Alderling M, Hogstedt C, Gustavsson P. Mortality among Swedish chimney sweeps (1952-2006): an extended cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69:41-47. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ward EM, Fajen JM, Ruder AM, Rinsky RA, Halperin WE, Fessler-Flesch CA. Mortality study of workers in 1,3-butadiene production units identified from a chemical workers cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103:598-603. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Malaguarnera M, Vacante M, Russo C, Gargante MP, Giordano M, Bertino G, Neri S, Malaguarnera M, Galvano F, Li Volti G. Rosuvastatin reduces nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with α-interferon and ribavirin: Rosuvastatin reduces NAFLD in HCV patients. Hepat Mon. 2011;11:92-98. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Steenland K, Palu S. Cohort mortality study of 57,000 painters and other union members: a 15 year update. Occup Environ Med. 1999;56:315-321. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chen R, Seaton A. A meta-analysis of mortality among workers exposed to organic solvents. Occup Med (Lond). 1996;46:337-344. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gibbs GW, Amsel J, Soden K. A cohort mortality study of cellulose triacetate-fiber workers exposed to methylene chloride. J Occup Environ Med. 1996;38:693-697. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chow WH, McLaughlin JK, Zheng W, Blot WJ, Gao YT. Occupational risks for primary liver cancer in Shanghai, China. Am J Ind Med. 1993;24:93-100. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Toro A, Ardiri A, Mannino M, Arcerito MC, Mannino G, Palermo F, Bertino G, Di Carlo I. Effect of pre- and post-treatment α-fetoprotein levels and tumor size on survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by resection, transarterial chemoembolization or radiofrequency ablation: a retrospective study. BMC Surg. 2014;14:40. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Heinemann K, Willich SN, Heinemann LA, DoMinh T, Möhner M, Heuchert GE. Occupational exposure and liver cancer in women: results of the Multicentre International Liver Tumour Study (MILTS). Occup Med (Lond). 2000;50:422-429. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chang CK, Astrakianakis G, Thomas DB, Seixas NS, Ray RM, Gao DL, Wernli KJ, Fitzgibbons ED, Vaughan TL, Checkoway H. Occupational exposures and risks of liver cancer among Shanghai female textile workers--a case-cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:361-369. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Oh JK, Weiderpass E. Infection and cancer: global distribution and burden of diseases. Ann Glob Health. 2014;80:384-392. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 117] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L. A review of human carcinogens--Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:321-322. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1935] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2011] [Article Influence: 134.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Coutlée F, Franco EL. Infectious agents. IARC Sci Publ. 2011;175-187. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Kew MC. Aflatoxins as a cause of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2013;22:305-310. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Carr BI, Guerra V, Steel JL, Lu SN. A comparison of patients with hepatitis B- or hepatitis C-based advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:309-315. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Stroffolini T, Spadaro A, Di Marco V, Scifo G, Russello M, Montalto G, Bertino G, Surace L, Caroleo B, Foti G. Current practice of chronic hepatitis B treatment in Southern Italy. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23:e124-e127. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Askarian M, Yadollahi M, Kuochak F, Danaei M, Vakili V, Momeni M. Precautions for health care workers to avoid hepatitis B and C virus infection. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2011;2:191-198. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:553-562. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 704] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 707] [Article Influence: 64.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Bosques-Padilla FJ, Vázquez-Elizondo G, Villaseñor-Todd A, Garza-González E, Gonzalez-Gonzalez JA, Maldonado-Garza HJ. Hepatitis C virus infection in health-care settings: medical and ethical implications. Ann Hepatol. 2010;9 Suppl:132-140. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. | Sinn DH, Lee J, Goo J, Kim K, Gwak GY, Paik YH, Choi MS, Lee JH, Koh KC, Yoo BC. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk in chronic hepatitis B virus-infected compensated cirrhosis patients with low viral load. Hepatology. 2015;62:694-701. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 97] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Grosso G, Mistretta A, Marventano S, Ferranti R, Mauro L, Cunsolo R, Proietti L, Malaguarnera M. Long-term persistence of seroprotection by hepatitis B vaccination in healthcare workers of southern Italy. Hepat Mon. 2012;12:e6025. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Yang HI, Yeh SH, Chen PJ, Iloeje UH, Jen CL, Su J, Wang LY, Lu SN, You SL, Chen DS. Associations between hepatitis B virus genotype and mutants and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1134-1143. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 458] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Malaguarnera G, Vacante M, Drago F, Bertino G, Motta M, Giordano M, Malaguarnera M. Endozepine-4 levels are increased in hepatic coma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9103-9110. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Saitta C, Tripodi G, Barbera A, Bertuccio A, Smedile A, Ciancio A, Raffa G, Sangiovanni A, Navarra G, Raimondo G. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA integration in patients with occult HBV infection and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2015;35:2311-2317. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 83] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S35-S50. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Hassan MM, Hwang LY, Hatten CJ, Swaim M, Li D, Abbruzzese JL, Beasley P, Patt YZ. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma: synergism of alcohol with viral hepatitis and diabetes mellitus. Hepatology. 2002;36:1206-1213. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 548] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 501] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Cha C, Dematteo RP. Molecular mechanisms in hepatocellular carcinoma development. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:25-37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Thorgeirsson SS, Grisham JW. Molecular pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2002;31:339-346. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1097] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1075] [Article Influence: 48.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Malaguarnera M, Scuderi L, Ardiri Al, Malaguarnera G, Bertino N, Ruggeri IM, Greco C, Ozyalcn E, Bertino E, Bertino G. Type II mixed cryoglobulinemia in patients with hepatitis C Virus: treatment with pegylated-interferon and ribavirin. Acta Medica Mediterranea. 2015;31:651. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Bertino G, Demma S, Ardiri A, Proiti M, Gruttadauria S, Toro A, Malaguarnera G, Bertino N, Malaguarnera M, Malaguarnera M. Hepatocellular carcinoma: novel molecular targets in carcinogenesis for future therapies. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:203693. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Bertino G, Di Carlo I, Ardiri A, Calvagno GS, Demma S, Mala-guarnera G, Bertino N, Malaguarnera M, Toro A, Malaguarnera M. Systemic therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma: present and future. Future Oncol. 2013;9:1533-1548. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Biondi A, Malaguarnera G, Vacante M, Berretta M, D’Agata V, Malaguarnera M, Basile F, Drago F, Bertino G. Elevated serum levels of Chromogranin A in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Surg. 2012;12 Suppl 1:S7. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Bertino G, Ardiri AM, Boemi PM, Ierna D, Interlandi D, Caruso L, Minona E, Trovato MA, Vicari S, Li Destri G. A study about mechanisms of des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin’s production in hepatocellular carcinoma. Panminerva Med. 2008;50:221-226. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 55. | Bertino G, Ardiri AM, Calvagno GS, Bertino N, Boemi PM. Prognostic and diagnostic value of des-γ-carboxy prothrombin in liver cancer. Drug News Perspect. 2010;23:498-508. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Bertino G, Ardiri A, Malaguarnera M, Malaguarnera G, Bertino N, Calvagno GS. Hepatocellualar carcinoma serum markers. Semin Oncol. 2012;39:410-433. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 122] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Bertino G, Neri S, Bruno CM, Ardiri AM, Calvagno GS, Mala-guarnera M, Toro A, Malaguarnera M, Clementi S, Bertino N. Diagnostic and prognostic value of alpha-fetoprotein, des-γ-carboxy prothrombin and squamous cell carcinoma antigen immunoglobulin M complexes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Minerva Med. 2011;102:363-371. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 58. | Sartori M, La Terra G, Aglietta M, Manzin A, Navino C, Verzetti G. Transmission of hepatitis C via blood splash into conjunctiva. Scand J Infect Dis. 1993;25:270-271. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 112] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Bertino G, Ardiri A, Proiti M, Rigano G, Frazzetto E, Demma S, Ruggeri MI, Scuderi L, Malaguarnera G, Bertino N. Chronic hepatitis C: This and the new era of treatment. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:92-106. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | MacCannell T, Laramie AK, Gomaa A, Perz JF. Occupational exposure of health care personnel to hepatitis B and hepatitis C: prevention and surveillance strategies. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:23-36, vii. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Yazdanpanah Y, De Carli G, Migueres B, Lot F, Campins M, Colombo C, Thomas T, Deuffic-Burban S, Prevot MH, Domart M. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus transmission to health care workers after occupational exposure: a European case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1423-1430. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 121] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Malaguarnera G, Giordano M, Nunnari G, Bertino G, Malagu-arnera M. Gut microbiota in alcoholic liver disease: pathogenetic role and therapeutic perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16639-16648. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 96] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Petrovic D, Stamataki Z, Dempsey E, Golden-Mason L, Freeley M, Doherty D, Prichard D, Keogh C, Conroy J, Mitchell S. Hepatitis C virus targets the T cell secretory machinery as a mechanism of immune evasion. Hepatology. 2011;53:1846-1853. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | O’Bryan JM, Potts JA, Bonkovsky HL, Mathew A, Rothman AL. Extended interferon-alpha therapy accelerates telomere length loss in human peripheral blood T lymphocytes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20922. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Pardee AD, Butterfield LH. Immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: Unique challenges and clinical opportunities. Oncoim-munology. 2012;1:48-55. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Bertino G, Ardiri A, Boemi PM, Calvagno GS, Ruggeri IM, Speranza A, Santonocito MM, Ierna D, Bruno CM, Valenti M. Epoetin alpha improves the response to antiviral treatment in HCV-related chronic hepatitis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:1055-1063. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Malaguarnera G, Pennisi M, Gagliano C, Vacante M, Mala-guarnera M, Salomone S, Drago F, Bertino G, Caraci F, Nunnari G. Acetyl-L-Carnitine Supplementation During HCV Therapy With Pegylated Interferon-α 2b Plus Ribavirin: Effect on Work Performance; A Randomized Clinical Trial. Hepat Mon. 2014;14:e11608. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Malaguarnera M, Vacante M, Giordano M, Motta M, Bertino G, Pennisi M, Neri S, Malaguarnera M, Li Volti G, Galvano F. L-carnitine supplementation improves hematological pattern in patients affected by HCV treated with Peg interferon-α 2b plus ribavirin. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4414-4420. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Malaguarnera M, Vacante M, Bertino G, Neri S, Malaguarnera M, Gargante MP, Motta M, Lupo L, Chisari G, Bruno CM. The supplementation of acetyl-L-carnitine decreases fatigue and increases quality of life in patients with hepatitis C treated with pegylated interferon-α 2b plus ribavirin. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:653-659. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Bruno CM, Valenti M, Bertino G, Ardiri A, Amoroso A, Consolo M, Mazzarino CM, Neri S. Relationship between circulating interleukin-10 and histological features in patients with chronic C hepatitis. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31:360-364. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Zhao F, Korangy F, Greten TF. Cellular immune suppressor mechanisms in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis. 2012;30:477-482. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Cai L, Zhang Z, Zhou L, Wang H, Fu J, Zhang S, Shi M, Zhang H, Yang Y, Wu H. Functional impairment in circulating and intrahepatic NK cells and relative mechanism in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Clin Immunol. 2008;129:428-437. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 211] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | El Ansary M, Mogawer S, Elhamid SA, Alwakil S, Aboelkasem F, Sabaawy HE, Abdelhalim O. Immunotherapy by autologous dendritic cell vaccine in patients with advanced HCC. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:39-48. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Strosnider H, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Banziger M, Bhat RV, Breiman R, Brune MN, DeCock K, Dilley A, Groopman J, Hell K. Workgroup report: public health strategies for reducing aflatoxin exposure in developing countries. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1898-1903. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 258] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Liu Y, Chang CC, Marsh GM, Wu F. Population attributable risk of aflatoxin-related liver cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:2125-2136. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 191] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Chemical agents and related occupations. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100:9-562. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 77. | Viegas S, Veiga L, Figueiredo P, Almeida A, Carolino E, Viegas C. Assessment of workers’ exposure to aflatoxin B1 in a Portuguese waste industry. Ann Occup Hyg. 2015;59:173-181. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Autrup JL, Schmidt J, Seremet T, Autrup H. Determination of exposure to aflatoxins among Danish workers in animal-feed production through the analysis of aflatoxin B1 adducts to serum albumin. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1991;17:436-440. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Diaz GJ, Murcia HW, Cepeda SM. Cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of aflatoxin B1 in chickens and quail. Poult Sci. 2010;89:2461-2469. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Lin ZH, Chen JC, Wang YS, Huang TJ, Wang J, Long XD. DNA repair gene XRCC4 codon 247 polymorphism modified diffusely infiltrating astrocytoma risk and prognosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:250-260. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Long XD, Yao JG, Zeng Z, Ma Y, Huang XY, Wei ZH, Liu M, Zhang JJ, Xue F, Zhai B. Polymorphisms in the coding region of X-ray repair complementing group 4 and aflatoxin B1-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;58:171-181. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Lai H, Mo X, Yang Y, He K, Xiao J, Liu C, Chen J, Lin Y. Association between aflatoxin B1 occupational airway exposure and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:9577-9584. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Hu T, Du Q, Ren F, Liang S, Lin D, Li J, Chen Y. Spatial analysis of the home addresses of hospital patients with hepatitis B infection or hepatoma in Shenzhen, China from 2010 to 2012. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:3143-3155. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Villar S, Ortiz-Cuaran S, Abedi-Ardekani B, Gouas D, Nogueira da Costa A, Plymoth A, Khuhaprema T, Kalalak A, Sangrajrang S, Friesen MD. Aflatoxin-induced TP53 R249S mutation in hepatocellular carcinoma in Thailand: association with tumors developing in the absence of liver cirrhosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37707. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Gouas D, Shi H, Hainaut P. The aflatoxin-induced TP53 mutation at codon 249 (R249S): biomarker of exposure, early detection and target for therapy. Cancer Lett. 2009;286:29-37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Kirk GD, Lesi OA, Mendy M, Szymañska K, Whittle H, Goedert JJ, Hainaut P, Montesano R. 249(ser) TP53 mutation in plasma DNA, hepatitis B viral infection, and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:5858-5867. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 137] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Jargot D, Melin S. Characterization and validation of sampling and analytical methods for mycotoxins in workplace air. Environ Sci Process Impacts. 2013;15:633-644. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Viegas S, Veiga L, Malta-Vacas J, Sabino R, Figueredo P, Almeida A, Viegas C, Carolino E. Occupational exposure to aflatoxin (AFB1) in poultry production. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2012;75:1330-1340. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Burg WA, Shotwell OL, Saltzman BE. Measurements of airborne aflatoxins during the handling of contaminated corn. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1981;42:1-11. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Viegas S, Faísca VM, Dias H, Clérigo A, Carolino E, Viegas C. Occupational exposure to poultry dust and effects on the respiratory system in workers. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2013;76:230-239. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Autrup JL, Schmidt J, Autrup H. Exposure to aflatoxin B1 in animal-feed production plant workers. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;99:195-197. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Ghosh SK, Desai MR, Pandya GL, Venkaiah K. Airborne aflatoxin in the grain processing industries in India. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1997;58:583-586. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Desai MR, Ghosh S. Occupational exposure to airborne fungi among rice mill workers with special reference to aflatoxin producing A. flavus strains. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2003;10:159-162. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 94. | Traverso A, Bassoli V, Cioè A, Anselmo S, Ferro M. Assessment of aflatoxin exposure of laboratory worker during food contamination analyses. Assessment of the procedures adopted by an A.R.P.A.L. laboratory (Liguria Region Environmental Protection Agency). Med Lav. 2010;101:375-380. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 95. | Long XD, Huang XY, Yao JG, Liao P, Tang YJ, Ma Y, Xia Q. Polymorphisms in the precursor microRNAs and aflatoxin B1-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2015; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Saad-Hussein A, Beshir S, Moubarz G, Elserougy S, Ibrahim MI. Effect of occupational exposure to aflatoxins on some liver tumor markers in textile workers. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56:818-824. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Levy BS, Wegman DH, Baron SL, Sokas RK. Occupational and Environmental Health: Recognizing and Preventing Disease and Injury. 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. 2011; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 98. | IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Volume 97. 1,3-butadiene, ethylene oxide and vinyl halides (vinyl fluoride, vinyl chloride and vinyl bromide). IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2008;97:3-471. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 99. | Lopez V, Chamoux A, Tempier M, Thiel H, Ughetto S, Trousselard M, Naughton G, Dutheil F. The long-term effects of occupational exposure to vinyl chloride monomer on microcirculation: a cross-sectional study 15 years after retirement. BMJ Open. 2013;3. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Uccello M, Malaguarnera G, Corriere T, Biondi A, Basile F, Malaguarnera M. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in workers exposed to chemicals. Hepat Mon. 2012;12:e5943. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Caponnetto P, Russo C, Di Maria A, Morjaria JB, Barton S, Guarino F, Basile E, Proiti M, Bertino G, Cacciola RR. Circulating endothelial-coagulative activation markers after smoking cessation: a 12-month observational study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41:616-626. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Kauppinen T, Toikkanen J, Pedersen D, Young R, Ahrens W, Boffetta P, Hansen J, Kromhout H, Maqueda Blasco J, Mirabelli D. Occupational exposure to carcinogens in the European Union. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57:10-18. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 247] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Dobecki M, Romanowicz B. [Occupational exposure to toxic substances during the production of vinyl chloride and chlorinated organic solvents]. Med Pr. 1993;44:99-102. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 104. | Fred C, Törnqvist M, Granath F. Evaluation of cancer tests of 1,3-butadiene using internal dose, genotoxic potency, and a multiplicative risk model. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8014-8021. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Maroni M, Mocci F, Visentin S, Preti G, Fanetti AC. Periportal fibrosis and other liver ultrasonography findings in vinyl chloride workers. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:60-65. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Dogliotti E. Molecular mechanisms of carcinogenesis by vinyl chloride. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2006;42:163-169. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 107. | Fedeli U, Mastroangelo G. Vinyl chloride industry in the cour-troom and corporate influences on the scientific literature. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54:470-473. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Lewis R, Rempala G, Dell LD, Mundt KA. Vinyl chloride and liver and brain cancer at a polymer production plant in Louisville, Kentucky. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:533-537. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Hsieh HI, Chen PC, Wong RH, Du CL, Chang YY, Wang JD, Cheng TJ. Mortality from liver cancer and leukaemia among polyvinyl chloride workers in Taiwan: an updated study. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68:120-125. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Mastrangelo G, Martines D, Fedeli U. Vinyl chloride and the liver: misrepresentation of epidemiological evidence. J Hepatol. 2010;52:776-777. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Dragani TA, Zocchetti C. Occupational exposure to vinyl chloride and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:1193-1200. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Mastrangelo G, Fedeli U, Fadda E, Valentini F, Agnesi R, Magarotto G, Marchì T, Buda A, Pinzani M, Martines D. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis in vinyl chloride workers: synergistic effect of occupational exposure with alcohol intake. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1188-1192. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Malaguarnera M, Motta M, Vacante M, Malaguarnera G, Caraci F, Nunnari G, Gagliano C, Greco C, Chisari G, Drago F. Silybin-vitamin E-phospholipids complex reduces liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with pegylated interferon α and ribavirin. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7:2510-2518. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 114. | Weihrauch M, Lehnert G, Köckerling F, Wittekind C, Tannapfel A. p53 mutation pattern in hepatocellular carcinoma in workers exposed to vinyl chloride. Cancer. 2000;88:1030-1036. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Weihrauch M, Benicke M, Lehnert G, Wittekind C, Wrbi-tzky R, Tannapfel A. Frequent k- ras -2 mutations and p16(INK4A)-methylation in hepatocellular carcinomas in workers exposed to vinyl chloride. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:982-989. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Feron VJ, Kruysse A, Til HP. One-year time sequence inhalation toxicity study of vinyl chloride in rats. I. Growth, mortality, haematology, clinical chemistry and organ weights. Toxicology. 1979;13:25-28. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 117. | Til HP, Feron VJ, Immel HR. Lifetime (149-week) oral carcino-genicity study of vinyl chloride in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 1991;29:713-718. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Ward E, Boffetta P, Andersen A, Colin D, Comba P, Deddens JA, De Santis M, Engholm G, Hagmar L, Langard S. Update of the follow-up of mortality and cancer incidence among European workers employed in the vinyl chloride industry. Epidemiology. 2001;12:710-718. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Wong RH, Chen PC, Du CL, Wang JD, Cheng TJ. An increased standardised mortality ratio for liver cancer among polyvinyl chloride workers in Taiwan. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:405-409. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Gennaro V, Ceppi M, Crosignani P, Montanaro F. Reanalysis of updated mortality among vinyl and polyvinyl chloride workers: Confirmation of historical evidence and new findings. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:21. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Bebarta V, DeWitt C. Miscellaneous hydrocarbon solvents. Clin Occup Environ Med. 2004;4:455-479, vi. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Malaguarnera G, Cataudella E, Giordano M, Nunnari G, Chisari G, Malaguarnera M. Toxic hepatitis in occupational exposure to solvents. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2756-2766. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 99] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | Chen R, Seaton A. A meta-analysis of painting exposure and cancer mortality. Cancer Detect Prev. 1998;22:533-539. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 124. | Porru S, Placidi D, Carta A, Gelatti U, Ribero ML, Tagger A, Boffetta P, Donato F. Primary liver cancer and occupation in men: a case-control study in a high-incidence area in Northern Italy. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:878-883. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 125. | IARC Monogr Evaluation Carcinogenesis Risks to Humans. Dry cleaning, some chlorinated solvents and other industrial chemicals. Lyon, France, 7-14 February 1995. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1995;63:33-477. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 126. | Alexander DD, Kelsh MA, Mink PJ, Mandel JH, Basu R, Weingart M. A meta-analysis of occupational trichloroethylene exposure and liver cancer. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2007;81:127-143. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 127. | Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Trichloroethylene Toxicological Review and Appendices. 2011;. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 128. | Bradford BU, Lock EF, Kosyk O, Kim S, Uehara T, Harbourt D, DeSimone M, Threadgill DW, Tryndyak V, Pogribny IP. Interstrain differences in the liver effects of trichloroethylene in a multistrain panel of inbred mice. Toxicol Sci. 2011;120:206-217. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 129. | IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene, and some other chlorinated agents. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2014;106:1-512. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 130. | Hansen J, Sallmén M, Seldén AI, Anttila A, Pukkala E, Andersson K, Bryngelsson IL, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Olsen JH, McLaughlin JK. Risk of cancer among workers exposed to trichloroethylene: analysis of three Nordic cohort studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:869-877. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 131. | Rusyn I, Chiu WA, Lash LH, Kromhout H, Hansen J, Guyton KZ. Trichloroethylene: Mechanistic, epidemiologic and other supporting evidence of carcinogenic hazard. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;141:55-68. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |