Published online Apr 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i4.402

Peer-review started: January 18, 2019

First decision: March 5, 2019

Revised: March 16, 2019

Accepted: April 8, 2019

Article in press: April 8, 2019

Published online: April 27, 2019

Infection by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) is currently considered to be a global health issue, with a high worldwide prevalence and causing chronic disease in afflicted individuals. The disease largely involves the liver but it can affect other organs, including the skin. While leukocytoclastic vasculitis has been reported as one of the dermatologic manifestations of HCV infection, there are no reports of this condition as the first symptom of HCV recurrence after liver transplantation.

We report here a case of leukocytoclastic vasculitis in a liver transplant recipient on maintenance immunosuppression. The condition presented as a palpable purpura in both lower extremities. Blood and urine cultures were negative and all biochemical tests were normal, excepting evidence of anemia and hypocomplementemia. Imaging examination by computed tomography showed a small volume of ascites, diffuse thickening of bowel walls, and a small bilateral pleural effusion. Skin biopsy showed leukocytoclasia and fibrinoid necrosis. Liver biopsy was suggestive of HCV recurrence in the graft, and HCV polymerase chain reaction yielded 11460 copies/mL and identified the genotype as 1A. Treatment of the virus with a 12-wk direct-acting antiviral regimen of ribavirin, sofosbuvir and daclatasvir led to regression of the symptoms within the first 10 d and subsequent complete resolution of the symptoms.

This case highlights the difficulties of diagnosing skin lesions caused by HCV infection in immunosuppressed patients.

Core tip: Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is an uncommon extrahepatic manifestation of infection by the hepatitis C virus (HCV). We report the case of a patient who underwent liver transplantation for the treatment of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma associated with HCV infection, and who developed skin lesions and systemic symptoms, such as fever, post-transplantation. A short time after HCV antiviral treatment was started, the patient showed complete regression of all symptoms. While there are previous reports of leukocytoclastic vasculitis in solid organ transplant recipients, we have found no previous case in the literature of this being a symptom of HCV recurrence in this context.

- Citation: Ferreira GSA, Watanabe ALC, Trevizoli NC, Jorge FMF, Diaz LGG, Araujo MCCL, Araujo GC, Machado AC. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis caused by hepatitis C virus in a liver transplant recipient: A case report. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(4): 402-408

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i4/402.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i4.402

Hepatitis C is a chronic liver disease caused by infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). According to the Global Hepatitis Report 2017, around 71 million people worldwide carry the HCV infection[1]. As this disease leads to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), it is currently one of the most common causes for liver transplant worldwide, being the main cause of liver transplant in the United States and Europe[1,2].

Recurrence of HCV after liver transplantation is a common event, occurring in practically all patients who were not successfully treated prior to the surgical procedure[3,4]. Diagnosis is made by either liver biopsy or detection of HCV in the blood via polymerase chain reaction (PCR). While the timing to recurrence varies among individuals, the manifestations of the HCV infection after the transplant are typically more aggressive than with the original infection due to the post-transplantation immunosuppressive drug regimen[3-5].

Infection by HCV is not limited to the liver and extrahepatic manifestations can include mixed cryoglobulinemia, insulin resistance, and depression, as well as cardiovascular, renal and dermatological diseases[6]. Among the dermatological manifestations in particular, the more common are late cutaneous porphyria, cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, lichen planus, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema nodosum, and necrolytic acral erythema[7].

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is an inflammatory syndrome that affects small-sized vessels, and the most prominent histological features are leukocytoclasia (neutrophil fragmentation) and fibrinoid necrosis[8]. It can develop secondary to drugs, infection, collagen disease, or cancer. The most common clinical presentation is a palpable purpura in the lower extremities[8,9], although cutaneous manifestations can also include petechiae, nodules or ulcers. Ultimately, skin biopsy is necessary for diagnostic confirmation[10,11].

Cases of leukocytoclastic vasculitis in organ transplant patients have been reported, but none of those previous cases have cited HCV recurrence as the underlying cause.

A 61-year-old female with cirrhosis due to chronic HCV infection, cirrhosis and HCC, underwent liver transplant.

At the time of transplantation, the patient’s model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score was 6 and Child-Pugh classification was grade A (5 points). Three years prior to the procedure, the patient had undergone treatment with pegylated-interferon and ribavirin for 1 year, achieving no sustained virologic response. The interferon had been discontinued, but the ribavirin had been continued as monotherapy for another 6 mo. At the end of treatment, the patient’s HCV RNA load was undetectable by PCR and the treatment had been considered effective. A screening ultrasound of the patient’s abdomen, however, showed a suspicious nodule in the liver. Computerized tomography (CT) scan revealed a hypervascular lesion with rapid washout, suggestive of HCC, measuring 38 mm × 36 mm in the liver segment IVA. This lesion had close contact with the middle hepatic vein and retrohepatic inferior vena cava, and was deemed to be unresectable.

The patient was submitted to orthotopic liver transplantation with a graft from a cadaveric donor (37-year-old male). Total ischemia time was 4 h and 41 min, with no intraoperative complications and no need for blood product transfusions. She was discharged from the intensive care unit 2 d after the procedure and from the hospital 8 d after the transplant.

At 5 mo after the surgery, the patient returned to the emergency room complaining of pain, swelling and redness on both lower extremities, associated with fever, diarrhea and vomiting.

The patient reported that the skin lesions appeared 17 d before she presented to the emergency room, and they had gradually increased in extension during that period. She had already presented to another institution and given treatment for a presumptive diagnosis of cellulitis, consisting of cephalexin and then amoxicillin–clavulanate for 1 wk. The treatment induced no improvement and her clinical condition worsened, as she developed diarrhea, vomiting and loss of appetite.

The patient had no previous history of skin disease and no significant comorbidities, other than HCV infection and the recent transplant. She reported contact with ticks 1 wk before the lesions appeared.

A painful palpable purpura was observed on both lower extremities, affecting the lateral and posterior aspect of the lower legs (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the hospital for investigation, and intravenous cefepime was started. In addition, a short course of doxycyclin was administered, to address the history of contact with ticks.

Blood and urine cultures were obtained, yielding negative results. Biochemical tests showed normal leukocyte and platelet counts, and levels of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase within the normal range (NR). Remarkable findings were anemia (hemoglobin concentration of 8.6 g/dL) and hypocomplementemia [C3 52 mg/dL (NR: 90-170), C4 < 2 mg/dL (NR: 12-36), total complement CH50 < 60 U/CAE (NR: 60-265)]. Tests for anti-RO, anti-LA, anti-DNA, anti-RNP, FAN, anti-SM, ANCA and lupic anticoagulant antibodies and cryoglobulins, as well as cytomegalovirus and Zika virus (by PCR), were negative.

During investigation, CT scans of chest and abdomen were carried out, as well as an echocardiogram. The CT showed a small volume of ascites, diffuse thickening of bowel walls, and a small bilateral pleural effusion (Figure 2). The echocardiogram was normal, with an ejection fraction of 67.45% and no pericardial effusion.

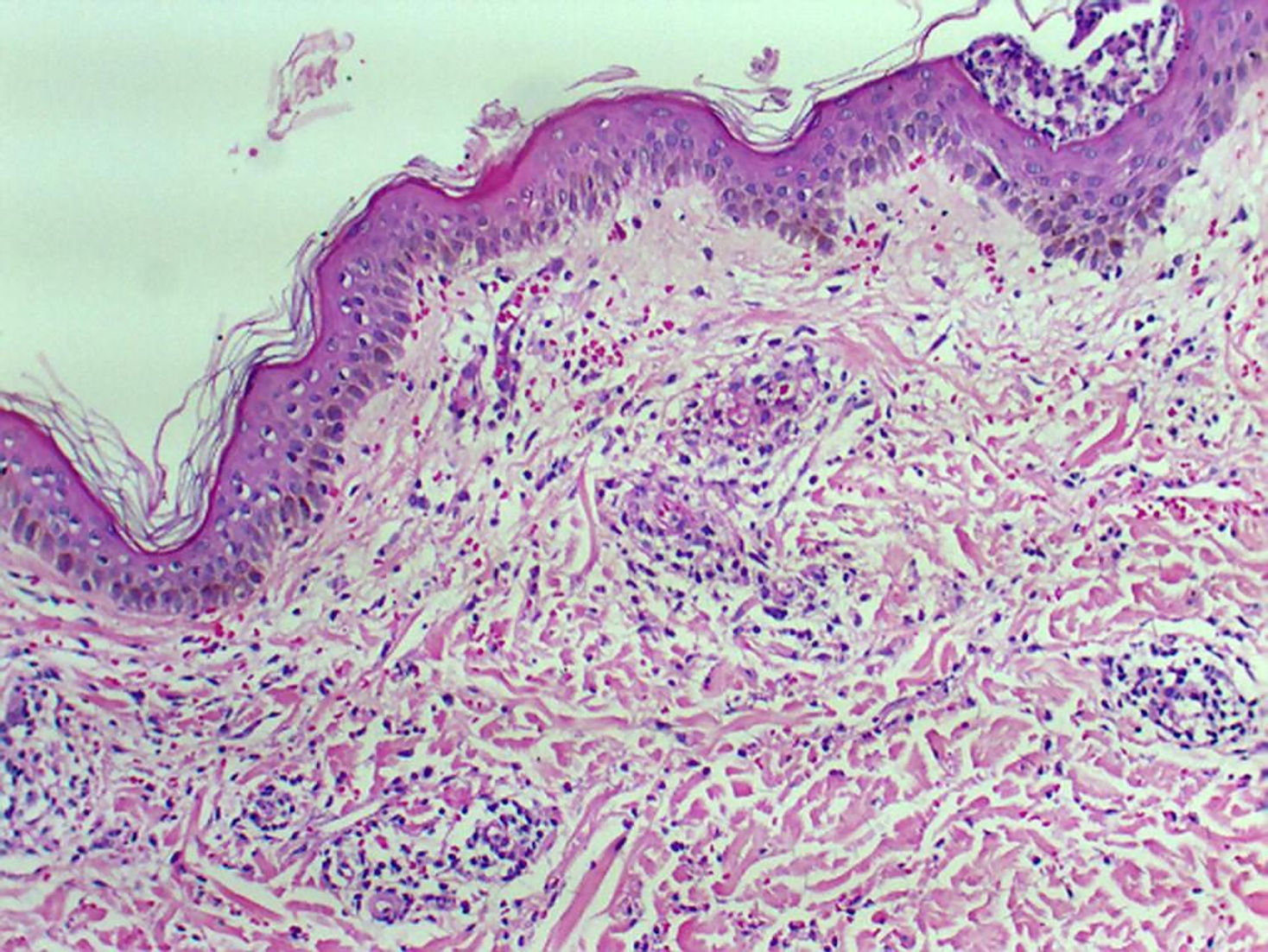

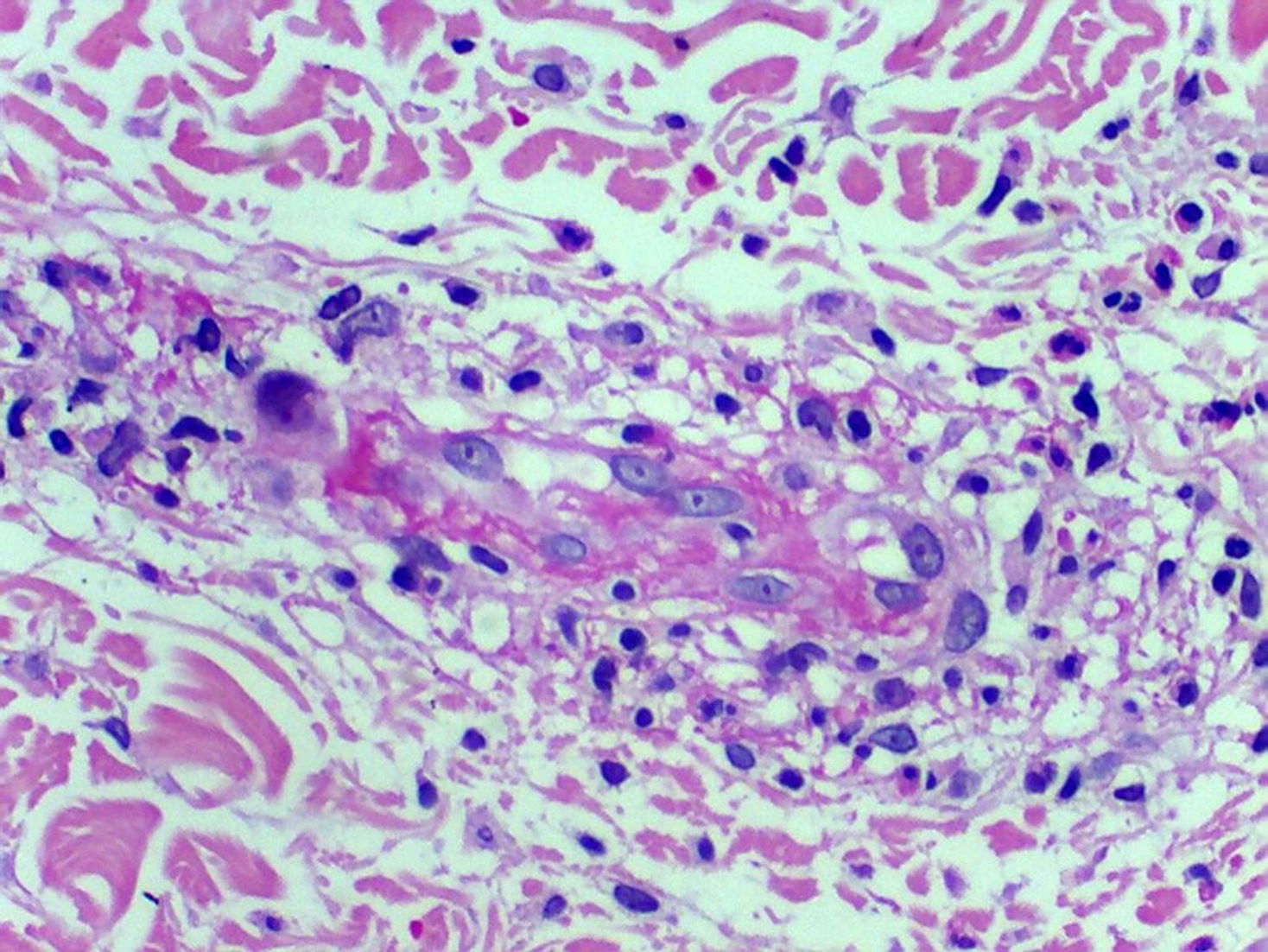

A skin biopsy was obtained from the patient’s left leg and investigated by histological analysis carried out by Dr. Silvia Conde Watanabe, an expert in skin pathologies.

Histology of the skin biopsy showed discrete acanthosis, and neutrophil and erythrocyte exocytosis in the epidermis (Figures 3 and 4). The superficial and medium dermis showed a moderate perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrate, with a predominance of neutrophils. Focal vasculitis was also found, characterized by small-size vessels surrounded by polymorphonuclear leukocytes and fibrinoid necrosis of their walls, along with eosinophil leukocytoclasia. A liver biopsy was also performed, and showed chronic hepatitis with moderate activity, suggesting HCV recurrence in the graft; METAVIR score of A2F1 was assigned. HCV PCR yielded 11460 copies/mL and identified the genotype as 1A.

A 12-wk antiviral regimen was initiated, consisting of sofosbuvir (400 mg/d), daclatasvir (60 mg/d) and ribavirin (1000 mg/d). The patient experienced no adverse effects associated with the treatment. After 10 d, all skin lesions showed appreciable regression, and the patient remained afebrile.

At the 6-mo follow-up after finishing the 12-wk treatment, the patient remained well and with normal graft function. Blood tests detected no HCV, and there was no fever or any other sign of vasculitis.

Reportedly, half of the patients infected with HCV develop chronic liver disease[12] and about 30% progress to hepatic cirrhosis, with many eventually needing a liver transplant[4]. After the transplant, there is a 50% recurrence rate of the virus within the first year, and recurrence within 5 years is an almost a universal phenomenon[4].

Besides the characteristic effects on the liver, HCV can affect other organs and systems as well. Indeed, 10%-15% of patients infected with HCV develop symptomatic extrahepatic disease[13]. A small portion (2%-4%) present to clinic with leukocytoclastic vasculitis, accounting for 8%-19% of all leukocytoclastic vasculitis cases[13,14].

The most frequent HCV subtype found in cases of human HCV infection is genotype 1, corresponding to roughly 70%-75% of the cases in the United States alone[12]. Unfortunately, this is also the subtype with the greatest resistance to interferon, requiring longer treatment duration and greater doses[7]. No studies in the current literature, however, have reported on the association of leukocytoclastic vasculitis with any particular HCV genotype.

The treatment of HCV-related leukocytoclastic vasculitis focuses on the virus itself, aiming to reduce or eradicate it[10,11]. Prednisone has been used successfully in some cases of vasculitis, but it has no curative effect and can increase the HCV viral load and associated damage to the liver[15]. One case of successful treatment with tiaprofenic acid and topical clobetazole has been reported from India, with the outcome being complete resolution after 3 wk of treatment[12].

The most important differential diagnoses of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are other vasculitis conditions, pigmented purpuric dermatosis, acute meningococcemia, disseminated gonococcal infection, disseminated intravascular coagulation, monoclonal paraproteinemia, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, Gardner-Diamond syndrome, atrial myxoma, cholesterol embolism and infectious emboli[16].

The challenge of correctly diagnosing HCV-associated leukocytoclastic vasculitis after liver transplantation lies in the great number of immunological and infectious agents that can cause similar skin lesions in immunosuppressed patients. Skin biopsy is of great importance in investigating these cases. Once specific treatment is initiated against HCV, the patient usually experiences a rapid recovery and has a favorable prognosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

CARE Checklist (2016): The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

P-Reviewer: Deneau M, Skrypnyk I, Wu C S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Global Burden of Hepatitis C Working Group. Global burden of disease (GBD) for hepatitis C. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:20-29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 389] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Grogan TA. Liver transplantation: issues and nursing care requirements. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2011;23:443-456. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2018. J Hepatol. 2018;69:461-511. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1163] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1123] [Article Influence: 187.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gitto S, Belli LS, Vukotic R, Lorenzini S, Airoldi A, Cicero AF, Vangeli M, Brodosi L, Panno AM, Di Donato R, Cescon M, Grazi GL, De Carlis L, Pinna AD, Bernardi M, Andreone P. Hepatitis C virus recurrence after liver transplantation: a 10-year evaluation. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3912-3920. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Coelho JC, Okawa L, Parolin MB, Freitas AC, Matias JE, Matioski AR. [Hepatitis C recurrence after living donor and cadaveric liver transplantation]. Arq Gastroenterol. 2009;46:38-42. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Negro F, Esmat G. Extrahepatic manifestations in hepatitis C virus infection. J Adv Res. 2017;8:85-87. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cacoub P, Comarmond C, Domont F, Savey L, Desbois AC, Saadoun D. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2016;3:3-14. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 104] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Carvalho M, Dominoni RL, Senchechen D, Fernandes AF, Burigo IP, Doubrawa E. Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis accompanied by pulmonary tuberculosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2008;34:745-748. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Einhorn J, Levis JT. Dermatologic Diagnosis: Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis. Perm J. 2015;19:77-78. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gumber SC, Chopra S. Hepatitis C: a multifaceted disease. Review of extrahepatic manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:615-620. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 314] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang F, Liu JH, Zhao YK, Luo DQ. Interferon-gamma-induced local leukocytoclastic vasculitis at the subcutaneous injection site. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:76-78. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mannu GS. An interesting rash: leucocytoclastic vasculitis with type 2 cryoglobulinaemia. JRSM Short Rep. 2010;1:54. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | El-Darouti MA, Mashaly HM, El-Nabarawy E, Eissa AM, Abdel-Halim MR, Fawzi MM, El-Eishi NH, Tawfik SO, Zaki NS, Zidan AZ, Fawzi M, Abdelaziz M, Fawzi MM, Shaker OG. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis and necrolytic acral erythema in patients with hepatitis C infection: do viral load and viral genotype play a role? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:259-265. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Polish Group of Experts for HCV, Halota W, Flisiak R, Juszczyk J, Małkowski P, Pawłowska M, Simon K, Tomasiewicz K. Recommendations for the treatment of hepatitis C in 2017. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2017;3:47-55. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dedania B, Wu GY. Dermatologic Extrahepatic Manifestations of Hepatitis C. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2015;3:127-133. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Charles ED, Dustin LB. Hepatitis C virus-induced cryoglobulinemia. Kidney Int. 2009;76:818-824. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 130] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |