修回日期: 2016-06-17

接受日期: 2016-06-27

在线出版日期: 2016-12-28

食管癌是消化系统最常见的恶性肿瘤之一, 我国食管癌的发病率及死亡率居世界第1位. 目前食管癌的治疗方式主要是内镜、手术、化疗和放疗. 这些传统治疗手段虽然取得了一定的临床效果, 但对生存期的改善并不明显. 目前的多项研究表明, 肿瘤免疫微环境在食管癌发生发展中起着很重要的作用. 已经完成和正在进行的食管癌免疫治疗的临床试验肯定了免疫治疗在食管癌中的巨大潜力. 免疫疗法与现有的或者新的治疗模式相结合将是食管癌治疗的最佳治疗策略.

核心提要: 肿瘤免疫治疗具有广阔的应用前景, 其在前列腺癌、黑色素瘤、肺癌和肾癌等恶性肿瘤中的广泛应用为食管癌免疫治疗的发展奠定了基础. 免疫治疗与现有的或者新的治疗模式相结合将是食管癌治疗的方向.

引文著录: 乔亚敏, 张毅. 食管癌免疫治疗的现状及展望. 世界华人消化杂志 2016; 24(36): 4739-4751

Revised: June 17, 2016

Accepted: June 27, 2016

Published online: December 28, 2016

Esophageal cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors of the digestive system, and China has the highest morbidity and mortality rates of esophageal cancer in the world. Currently, main therapies for esophageal cancer include endoscopy, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. These traditional treatments have appreciated clinical effects, but the prognosis of this malignancy is still poor. There is accumulating evidence that tumor immune microenvironment plays a key role in the development and progression of esophageal cancer. Recent clinical investigations and ongoing studies indicate that immunotherapy might have a great potential in the treatment of patients with esophageal cancer. Future studies will identify treatment strategies that can maximize therapeutic benefits by combining immunotherapies with existing and novel treatment modalities.

- Citation: Qiao YM, Zhang Y. Immunotherapy for esophageal cancer: Current studies and future perspectives. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2016; 24(36): 4739-4751

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v24/i36/4739.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v24.i36.4739

食管癌是发生于食管黏膜上皮组织的恶性肿瘤, 其发病率和死亡率分别居于全球恶性肿瘤第8位和第6位[1]. 我国食管癌发病率和死亡率位居世界第1位. 食管癌主要的病理类型有鳞癌和腺癌. 食管癌发病率随年龄增加而增长, 发病高峰年龄为70-80岁. 食管腺癌男性发病率约为女性3-4倍, 而食管鳞癌在性别上没有显著差异[2].

近几十年来, 食管癌诊断和治疗方面的研究取得了一定进展, 但中晚期的食管癌患者5年生存率仍低于15%. 目前化疗在姑息性治疗中起着中流砥柱的作用, 但其客观缓解率仅为20%-40%, 中位生存期约为8-10 mo[3]. 因此, 迫切需要探索出能够显著改善食管癌患者预后的治疗方式.

近二十年来, 随着肿瘤免疫学的研究深入, 肿瘤免疫治疗已经成为国内外研究的热点之一. 2013-12-20, 肿瘤免疫治疗被Science列为年度科学突破之首. 目前, 一些用于癌症患者免疫治疗的方案已通过了美国食品和药物管理局(Food and Drug Administration, FDA)和欧洲药品监管机构的审批, 被广泛用于前列腺癌、黑色素瘤、肺癌和肾癌等疾病, 并取得了一定的临床疗效, 为其在食管癌等其他实体瘤的临床研究奠定了基础. 本文将针对食管癌免疫微环境及免疫治疗的主要研究现状及临床应用前景进行综述.

食管癌的治疗和预后依赖于精确评估癌症浸润的深度和淋巴结的侵犯程度, 内镜超声和PET检查的应用进一步完善了分期[4]. 无禁忌证或合并症0期或Ⅰ期的腺癌患者首选内镜治疗[5]. 已经侵犯到黏膜肌层并进入黏膜下层的T1b肿瘤, 根治性食管切除是优先选择的方案[6]. 局部进展期肿瘤最佳治疗手段是根治性食管切除, 根治性放化疗也能达到治疗目的[7], 新辅助化放疗或化疗的应用亦能提高临床治疗效果[8-10]. 姑息性化疗则常用于治疗不能切除的、转移或复发的晚期食管癌[11,12]. 此外, 多西他赛联合雷莫芦单抗也取得一定疗效, 而曲妥珠单抗单一使用增加晚期食管腺癌总生存期(overall survival, OS)和无进展生存期(progression-free survival, PFS)分别为2.7 mo和1.7 mo[13-15].

尽管如此, 中晚期的食管癌患者5年生存率仍低于15%; 局部进展期患者单纯手术治疗5年生存率仅有20%-25%[16,17], 术后联合放化疗或新辅助放化疗的5年生存率也只有30%-35%[18-20]. 食管癌预后较差原因之一是疾病进展较快, 其次是超过50%的患者在确诊时已出现了可见的转移灶[16]. 因此, 进一步探讨食管癌微环境及其对疾病进展的影响将为食管癌早期诊断和治疗改善奠定坚实的理论基础.

早在100年前, Paget[21]已提出了"种子与土壤"的假说, 为肿瘤微环境这一概念的提出奠定了基础. 大量数据表明肿瘤微环境中许多免疫相关的细胞和因子及免疫相关的信号通路在肿瘤的发生、转移、复发、血管形成及耐药等各个方面发挥着重要的作用[1,22]. 肿瘤免疫微环境的深入研究是寻找食管癌分子发病机制和新治疗模式的重要环节.

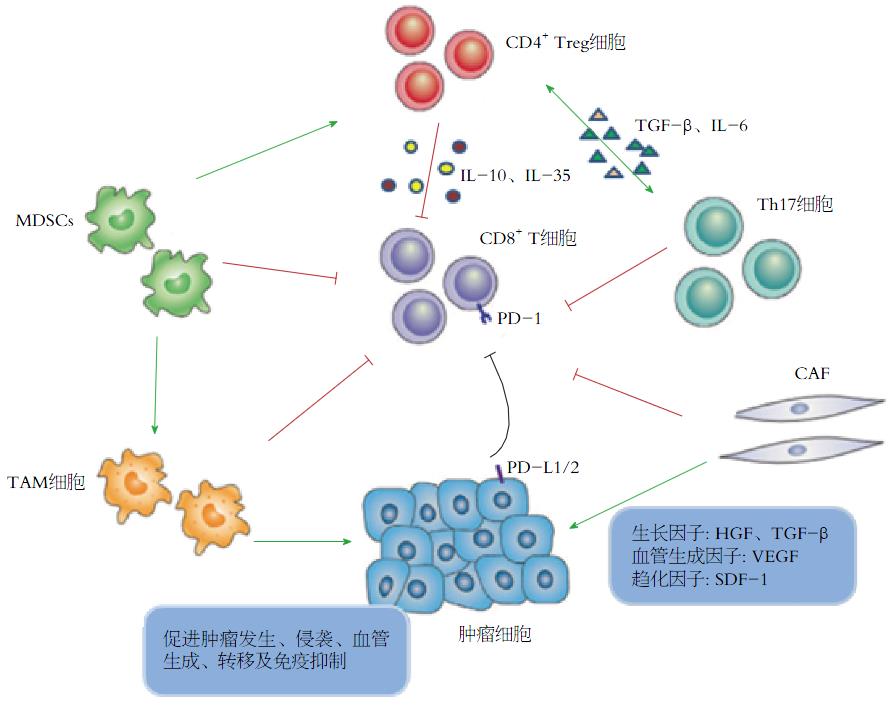

癌细胞周围的各种免疫细胞、成纤维细胞、内皮细胞、血管旁细胞、神经细胞、脂肪细胞及细胞外基质成分构成了肿瘤微环境[23-25]. 其通过抑制癌细胞凋亡、促进增殖、血管形成、耐药及免疫逃逸等机制来发挥促肿瘤作用(图1)[26].

肿瘤微环境中部分基质细胞抑制免疫效应细胞的功能、促进肿瘤进展. 肿瘤细胞或肿瘤相关巨噬细胞(tumor-associated macrophages, TAMs)分泌的趋化因子CCL17和CCL22招募CCR4+调节性T细胞(regulatory T cells, Treg), 后者通过直接接触或分泌细胞因子[白介素(interleukin, IL)-10和IL-35]抑制免疫效应细胞. 在IL-6和转化生长因子-β(transforming growth factor-β, TGF-β)刺激下, Th17细胞可转变为Treg细胞. 炎症和肿瘤衍生因子刺激激活髓系来源的抑制性细胞(myeloid-derived suppressor cells, MDSCs), 活化的MDSCs可以直接抑制CD8+ T细胞的活化、诱导Treg细胞等机制来实现免疫逃逸. TAM细胞和CAF细胞通过分泌细胞因子、趋化因子以及各种生长因子促进肿瘤细胞的生长、侵袭、转移及血管形成. 此外, 肿瘤细胞和TAM细胞可表达程序性死亡受体(programmed cell death ligand, PD)-L1/2, 与PD-1结合后抑制T细胞活化.

MDSCs已经被证实在促进肿瘤免疫逃逸、CAF细胞活化及血管形成方面发挥着重要作用[27]. 食管癌微环境中促炎因子如IL-1β、IL-6和前列腺素等的存在可以激活MDSC[28]. MDSC通过直接抑制T细胞的活化[29]、自然杀伤细胞(natural killer cell, NK)的细胞不良反应[30]、精氨酸和半胱氨酸的消耗和诱导Treg细胞等机制来实现免疫逃逸[31,32]. 另一群发挥相似功能的免疫抑制细胞就是Treg细胞. 在生理条件下, Treg细胞可以调节T细胞、B细胞的活化增殖和NK细胞的细胞毒性, 然而在肿瘤微环境中却可以通过分泌免疫抑制相关因子、干扰肿瘤相关抗原(tumor-associated antigens, TAAs)的提呈和抑制免疫效应细胞的细胞不良反应及颗粒酶释放等途径来促进肿瘤的发生和进展[33,34]. 研究表明肿瘤细胞及TAMs可以通过分泌CCL17和CCL22等趋化因子来招募CCR4+的Treg细胞到达肿瘤部位[35,36]. 而肿瘤部位高度聚集的Treg细胞促进肿瘤的浸润和转移, 且与疾病严重程度、化疗后生存率及预后相关[37-39]. 此外, Th17细胞可以通过分泌IL-17和IL-22、激活STAT3相关信号通路来促进血管形成和肿瘤生长[40]. 然而目前Th17细胞的作用仍然存在争议, 究竟是哪些因子影响了Th17的功能也还没有被很好的定义[40,41]. 因此, 我们尚需要更深一步的了解Th17细胞在食管癌中的作用来发掘潜在的治疗靶点.

TAMs有着各种各样的致瘤机制. 巨噬细胞表型频谱范围从M1型到M2型: M1型巨噬细胞代表着经典活化的巨噬细胞, 有分泌细胞因子, 抗原提呈, 抵抗感染和抗肿瘤等功能. 而M2型巨噬细胞则通过分泌Ⅱ型细胞因子、诱导活化COX2/前列腺素E等机制来产生促瘤作用[42-44]. 食管癌患者癌相关成纤维(cancer-associated fibroblasts, CAFs)的存在与微血管密度相关, 也可通过上皮细胞间质化(epithelial-mesenchymal transition, EMT)促进肿瘤进展和转移[45], CAFs也与放化疗后3年生存率和疾病复发有关[46].

PD-1为CD28超家族成员, 是一种重要的免疫抑制分子, 与其配体PD-L1/PD-L2结合后抑制T细胞的活化[47,48]. 多次实验证实PD-L1和PD-L2在食管癌中高度表达[49,50], 其中PD-L1的表达与肿瘤浸润深度和不良预后密切相关, 而PD-L2的表达与CD8+ T细胞浸润减少相关[50]. PD-L2表达的增加可以促肿瘤的Th2细胞因子如IL-4/IL-13分泌[48]. 这些证据表明PD-1的靶向阻断剂在食管癌的治疗中有重大的意义[51].

在食管癌早期阶段, TGF-β信号通过下调Smad4和c-Myc基因的表达来抑制肿瘤的生长, 而在晚期食管癌中则促进其生长和EMT[52,53]. 这种"开关"作用被认为是衔接蛋白的丢失导致的. 例如β2-血影蛋白就是细胞-细胞相互作用和上皮细胞极性维护中的一种重要衔接蛋白. 在食管腺癌中, 肿瘤细胞中β2-血影蛋白的丢失导致SOX9和c-Myc的表达增加, 但同时也减少了其他TGF-β靶点如E-cadherin和细胞周期调控的p21和p27[54]. 总之, 这些变化使得TGF-β促进了肿瘤的进展并通过促进EMT导致肿瘤的转移.

除了生长因子, 肿瘤微环境中的趋化因子在肿瘤的发生发展中也有着不可忽视的作用. 其中, 主要有成纤维细胞分泌的基质细胞衍生因子-1(stromal cell derived factor-1, CXCL12)[55], 与其相应受体CXCR4或CXCR7结合后可以诱导肿瘤细胞的生长、促进血管生成、刺激运动、侵袭和转移[56]. SDF-1/CXCR4/CXCR7轴与肿瘤侵袭转移以及生存密切相关, 但是用这些独立的组件作为预后分析的指标已经出现了不一致的结果[57]. 尽管如此, 在食管腺癌中SDF-1在体内和体外试验中被证明可以调节CXCR4阳性的肿瘤细胞的迁移. 通过小干扰RNA敲除CXCR4在KYSE-150和TE-13细胞中的表达能够抑制肿瘤细胞的增殖、侵袭和转移能力. 食管鳞癌局部CCL5和CXCL10可招募CD8+ T细胞到达肿瘤部位[58,59].

食管癌免疫微环境的基质成分形成了阻碍免疫效应细胞募集和发挥功能的屏障, 同时为肿瘤细胞的增殖、侵袭和转移提供了土壤. 通过各种手段调节机体的免疫状态达到重塑食管癌免疫微环境的作用将是食管癌免疫治疗的主要研究方向.

肿瘤免疫治疗是通过调节机体的免疫状态进而达到预防和治疗恶性肿瘤的一种治疗方法. 以细胞因子、肿瘤疫苗、过继细胞治疗(adoptive cell therapy, ACT)和免疫检查点阻断剂为代表的免疫治疗已经在临床应用中显示了巨大的临床疗效[3,60,61]. 在此将集中探讨肿瘤疫苗、ACT和免疫检查点阻断剂3种免疫治疗策略在食管癌治疗中的研究进展. 食管癌免疫治疗相关的临床试验详如表1.

| 类别 | 肿瘤 | 治疗手段 | 研究期别 | NCT编号 |

| ACT | ||||

| 食管癌 | CIK | Ⅱ期 | NCT02490735 | |

| 多种癌症(包括食管癌) | CTL | Ⅰ期 | NCT00004178 | |

| 食管癌 | NY-ESO-1-TCR T细胞 | Ⅱ期 | NCT01795976 | |

| 肿瘤疫苗 | ||||

| 细胞疫苗 | 多种癌症(包括食管癌) | 肿瘤细胞疫苗 | Ⅰ期 | NCT01258868 |

| 多种癌症(包括食管癌) | H1299溶解产物疫苗 | Ⅰ/Ⅱ期 | NCT02054104 | |

| 多种癌症(包括食管癌) | 同种异体肿瘤疫苗 | Ⅰ期 | NCT01143545 | |

| 肽疫苗 | 食管癌 | IMF-001 | Ⅰ期 | NCT01003808 |

| 食管癌 | LY6K, VEGFR1, VEGFR2 | Ⅰ期 | NCT00561275 | |

| 食管癌 | URLC10, TTK, KOC1, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, 顺铂, 氟尿嘧啶 | Ⅰ期 | NCT00632333 | |

| 食管癌 | URLC10 | Ⅰ期 | NCT00753844 | |

| 食管癌和胃癌 | G17DT, 顺铂, 氟尿嘧啶 | Ⅲ期 | NCT00020787 | |

| 多种癌症(包括食管癌) | 癌胚抗原肽1-6D | Ⅱ期 | NCT00012246 | |

| 靶向治疗 | ||||

| PD-L1单抗 | 局部进展和转移的实体肿瘤(包括食管癌) | Atezolizumab(PD-L1单抗) | Ⅰ期 | NCT01375842 |

| PD-1单抗 | 食管癌和胃癌 | Pembrolizumab(PD-1单抗) | Ⅱ期 | NCT02559687 |

| 一线方案耐药的食管癌和胃癌 | Pembrolizumab联合化疗药物 | Ⅲ期 | NCT02564263 | |

| 晚期恶性肿瘤(包括食管癌) | PDR001(PD-1单抗) | Ⅱ期 | NCT02460224 | |

| CTLA-4单抗 | 食管癌和胃癌 | Ipilimumab(CTLA-4单抗) | Ⅱ期 | NCT01585987 |

| 食管癌和胃癌 | Tremelimumab(CTLA-4单抗) | Ⅱ期 | NCT02340975 |

肿瘤疫苗治疗是通过向患者体内导入TAAs来激发患者的特异性抗肿瘤免疫反应. Rosenberg等[62,63]针对2004年之前开展的1306项癌症疫苗研究进行全面审查, 发现总体目标反应率仅为3.3%. 猜测可能是免疫细胞亲和力低或者受到内源性因素抑制等原因造成这些不理想的结果.

针对食管癌的治疗, 一些基于疫苗的临床试验报告已经公布. 一项使用肽疫苗治疗10例难治性Ⅲ或Ⅳ期食管鳞癌患者的Ⅰ期临床试验发现9例患者出现了抗原特异性T细胞免疫应答. 其中1例肝转移的患者出现了持续7 mo的完全缓解, 另有1例患者所有的肺转移病灶出现部分缓解, 还有3例患者无进展生存期持续了2.5 mo. 该试验使用的肽疫苗来源于3种HLA-A24限制性癌睾抗原(TTK蛋白激酶、淋巴细胞抗原6复合物基因座K和胰岛素样生长因子-Ⅱ mRNA结合蛋白3)[64]. 紧接着, 针对该疫苗的多中心的Ⅱ期临床试验也顺利开展. 该试验评估了HLA-A*2402阳性和阴性食管鳞癌患者在疫苗应用后OS、PFS和免疫应答情况. 结果显示, 在HLA-A*2402阳性患者(n = 35)中观察到了免疫应答, 但是相对于HLA-A*2402阴性患者(n = 25)其OS并没有统计学的差异(4.6 mo vs 2.6 mo, P>0.05), 而PFS则有明显的差异(P = 0.032)[65]. 在Saito等[66]主持的一项肿瘤疫苗试验(n = 20)中, 4例自身肿瘤细胞高度表达MAGE-A4或者MHC Ⅰ类抗原的患者在接种疫苗后不仅观察到MAGE-A4特异性免疫应答, 并且相对于没有免疫抗体的患者其OS明显延长. Wada等[67]以NY-ESO-1作为癌症疫苗在8例食管癌患者中进行试验, 结果显示7例患者出现免疫应答. 在参与临床效果评估的6例患者中, 1例患者出现部分缓解, 2例患者持续维持在无进展状态, 另有2例患者出现混合临床反应. 鉴于这些肽疫苗在临床试验中的初步成果, 其安全性检验及与放疗化疗相结合的相关研究也正逐步开展.

ACT的概念由Dietrich等[68]于1955年最早提出, 是指通过一定手段将自体或异体免疫细胞在体外扩增后回输入患者体内, 直接杀伤肿瘤和调动机体的免疫功能对抗肿瘤的治疗方法. 目前常用效应细胞可分为两类: 第一类为肿瘤抗原非特异性免疫细胞, 包括自体淋巴因子激活的杀伤细胞、细胞因子诱导的杀伤细胞(cytokine-induced killer, CIK)及NK细胞, 这类细胞通过从外周血细胞中分离并经淋巴因子或细胞因子诱导刺激获得; 另一类效应细胞为肿瘤抗原特异性T细胞, 包括肿瘤浸润性淋巴细胞(tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, TIL)、细胞毒性T细胞(cytotoxic T lymphocyte, CTL)以及经基因工程化的T细胞包括T细胞受体转导的T细胞(T cell receptor transferred T-cells, TCR-T)和嵌合抗原受体修饰T细胞(chimeric antigen receptors modified T-cells, CAR-T)[69,70].

首次ACT的人体试验通过回输CIK和重组IL-2来提高转移性癌症患者的生存, 该方案已成功应用于治疗难治性转移性黑色素瘤, 而对于其他类型的癌症比如脑胶质瘤、肾细胞癌、非小细胞肺癌等, 其客观缓解率从20%-72%不等[16,71,72].

迄今为止, 食管癌的ACT治疗已经有若干临床试验评价. 由Besser等[73]和Toh等[74]首次公布的研究中, 从食管鳞癌患者外周血中分离出单个核细胞, 在体外给予自体肿瘤细胞刺激, 将获得的CTL联合IL-2借助内窥镜注入肿瘤部位或直接注射到转移灶内. 后期结果显示一半的患者出现了客观反应, 其中36%的受试者达到了完全缓解或部分缓解. CTL和TIL细胞是开展实体肿瘤免疫治疗的热点, 其杀瘤机制明确. 但从肿瘤患者的外周血和组织中很难获取足够数量的抗原特异性T细胞用于回输. 基因工程修饰的肿瘤特异性T细胞的开发解决了这一难题, 在恶性肿瘤的ACT中具有巨大的应用前景.

TCR-T细胞是将抗原特异性的高亲和性TCR的α和β链转入T细胞并表达在细胞表面, 进而有效识别并杀伤表达该抗原的肿瘤细胞. 目前食管癌中常见的TAAs有癌睾抗原MAGE-A3/4和NY-ESO-1. 多项研究[75-77]表明MAGE-A3在食管癌中表达比例约为90%, NY-ESO-1在食管癌中表达比例高达40%-90%. 近期, 由Kageyama等[78,79]开展的一项基因工程化T细胞Ⅰ期临床试验前期, 向MAGE-A4阳性的复发的食管癌患者回输TCR-T细胞, 并后续应用MAGE-A4肽疫苗, 连续5 mo检测10例受试者外周血中TCR-T细胞, 其中5例受试者可持续检测到特异性T细胞. 7例受试者在治疗2 mo后出现了进展, 但另外3例受试者存活时间超过了27 mo.

CAR-T细胞为基因工程化T细胞的另一种类型. CARs是将靶抗原相对应抗体的单链可变区和T细胞信号分子融合而成能够特异性识别并结合TAAs的嵌合受体, 将CARs这样一种嵌合抗原受体的结构通过基因工程转入T细胞后获得CAR-T. 1989年Gross等[80]首次将CARs的结构成功构建进入T细胞使其发挥特异性杀伤功能. 截止到目前, 已经公布20余项关于CAR-T治疗恶性血液系统肿瘤的临床试验数据. 以CD19为靶向的CAR-T细胞在淋巴瘤和B细胞白血病的Ⅰ、Ⅱ期临床试验中显示了良好的抗肿瘤作用[81-84]. 针对实体瘤的CAR-T疗法, 早期一代CAR应用于临床并未出现理想的结果[85], 根源在于实体瘤缺乏独特的TAAs, T细胞归巢至肿瘤位点的效率低、持久性差, 瘤内免疫抑制环境强烈抑制CAR-T细胞功能. 应用二代或者三代CAR技术靶向实体瘤的临床试验尽管比较有限, 但一些比较可观的临床试验结果正逐步揭晓. 其中一项针对19例转移或复发HER2阳性肉瘤的患者, 应用HER2-CAR-T治疗后4例患者出现了12 wk-14 mo的病情稳定状态[86]. 近期, Feng等[87]公布的一项EGFR-CAR-T治疗EGFR阳性复发/难治的非小细胞肺癌患者的临床试验结果显示, 11例参与评价的患者中2例患者出现了部分缓解, 5例患者出现了2-8 mo不等的病情稳定状态, 整个临床试验中未出现明显的不良反应. 在食管癌的治疗方面, 目前还未开展CAR-T疗法相关研究. 但食管癌中不断涌出的抗肿瘤靶点如HER2[88], 也为下一步研究的开展提供了参考依据.

近年来, PD-1/PD-L1阻断剂在黑色素瘤和肺癌的治疗中取得了鼓舞人心的临床效果[89,90]. 关于PD-1阻断剂在食管癌治疗中的潜在作用, 可以透过肿瘤免疫微环境的基因组图谱的分析结果来预测. 从食管癌肿瘤组织中分离出的MDSC上PD-L1的表达有显著的上调, 约60%的食管癌组织TIL中能检测到PD-1的表达[47,91]. 值得注意的是, PD-1及其配体的高度表达与患者较差预后呈明显相关性[49]. 因此, 抑制PD-1/PD-L1通路对于食管癌的治疗有着不可忽视的价值.

目前, 关于PD-1或PD-L1阻断剂治疗食管癌的临床试验的结果尚未公布. 但正在进行研究的初步结果表明PD-1阻断剂Pembrolizumab在PD-L1阳性表达的食管癌患者有可接受的安全性. 中期分析客观缓解率约为30%, 持续反应期长达40 wk[92]. 这些结果为继续完成Pembrolizumab在食管癌患者应用的关键性研究奠定了基础.

细胞毒性T淋巴细胞相关分子4(cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4, CTLA-4), 也称为CD152属于免疫球蛋白超家族, 可作为免疫检查点. 当活化CD4+辅助性T细胞表面表达CTLA-4, 该类细胞就会向T细胞发送抑制性信号[93]. 而高度表达CTLA-4的CD4+ Treg细胞则通过减少IL-2的分泌和下调IL-2受体的表达将T细胞阻滞在细胞周期的G1期[94,95]. Ipilimumab和Tremelimumab两个完全人源化的单克隆抗CTLA-4抗体已获得FDA批准用于治疗黑色素瘤和间皮瘤[96,97]. 近期一项调查Tremelimumab针对晚期胃癌和食管癌治疗有效性的Ⅱ期临床试验(n = 18)已经完成. 尽管只观察到了5%的反应率, 但其中4例患者病情得到控制, 1例患者在8周期(25.4 mo)治疗后出现了部分缓解并持续了数月[98]. 正在进行的临床试验结果预计将进一步凸显出单克隆抗CTLA-4抗体在食管癌中的临床应用价值.

肿瘤的治疗目前已经进入了综合治疗的时代, 临床实践证明采用任何单一的治疗方法都难以取得最佳的效果. 因此, 除一些早期肿瘤和个别特殊类型的肿瘤以外, 绝大多数肿瘤的治疗原则是综合治疗. 新近的研究结果表明, 免疫治疗和化疗的联合使用在多种肿瘤治疗中取得了较单一疗法更优的效果. 大量的研究证明, 免疫治疗与化疗的联合使用具有多项优点, 他不仅能逆转肿瘤晚期导致的免疫抑制、提高肿瘤抗原的交叉提呈作用、促进杀伤性T细胞增殖并使其更易杀伤肿瘤细胞, 还可以在一定程度上减少化疗的不良反应以及减缓肿瘤细胞耐药性的发生[99-101]. 在免疫治疗与手术相结合的研究中, 多项研究[102,103]发现DC-CIK细胞治疗在清除微小残留病灶、预防肿瘤复发转移、提高治愈率方面具有良好的临床价值. 而在食管癌治疗中, 免疫治疗与放疗的结合则显示出更加突出的临床效果. 放射治疗是食管癌治疗的关键组成部分, 通过水分子和羟自由基介导的DNA链的断裂来杀伤肿瘤细胞. 在这过程中, DNA的损伤可改变基因的表达, 进而使肿瘤细胞表型发生了变化, 相当于为破坏免疫系统的肿瘤细胞进行"标记"[104]. 大量数据表明放疗能改变局部肿瘤的微环境, 这为放疗与免疫治疗的结合提供了有力证据[105,106].

免疫疗法在一些肿瘤中取得成功是多年来对免疫系统进行研究的结果, 也表明其在癌症治疗中作出了贡献. 更值得一提的是, 若干种免疫检查点阻断剂也已经或正在被FDA批准, 预计下一步将加快步伐以单药或者与其他治疗模式相结合应用于临床[107,108]. 然而, 机遇与挑战并存, 在免疫治疗中仍有些关键问题并未回答. 首先, 许多治疗癌症的靶向分子药物, 如何确定以最小的毒性取得最大临床获益的生物学剂量仍需探究; 其次, 鉴于当前大多数的免疫疗法主要是通过激活免疫系统来发挥抗肿瘤效应, 他要求患者在接受初始免疫治疗之前存在一定程度的免疫力. 因此, 全面评估患者的免疫状态和寻找预测免疫治疗效果的生物标志物势在必行. 此外, 大量证据表明辐射和化疗药物的暴露可能影响肿瘤细胞DNA突变率, 促使一些新抗原的形成. 当前的免疫治疗与放化疗联合应用时, 确定放疗的剂量、强度及持续时间, 或者定时放化疗是联合治疗取得最大效益的先决条件.

免疫治疗在恶性肿瘤的治疗中具有广阔的应用前景. 食管癌细胞高频率的突变以及在其他胃肠道恶性肿瘤中免疫治疗凸显的有效成果为食管癌免疫治疗的研究提供了有力证据. 采取免疫疗法与现有的或者新的治疗模式相结合的治疗策略将是今后食管癌治疗的方向.

2006年美国癌症年会上Steven Rosenberg博士指出: "免疫治疗是目前知道的唯一一种有望完全消灭癌细胞的治疗手段, 有可能取代目前的放化疗手段; 21世纪将是肿瘤生物治疗的世纪". 2013-12-20, 肿瘤免疫治疗被Science列为年度科学突破之首.

肿瘤免疫治疗是通过调节机体的免疫状态进而达到预防和治疗恶性肿瘤的一种治疗方法. 以细胞因子、肿瘤疫苗、过继细胞治疗(adoptive cell therapy, ACT)和免疫检查点阻断剂为代表的免疫治疗已经在临床应用中显示了巨大的临床疗效. 针对食管癌的治疗已经开展了几十项临床试验, 其中食管癌的ACT治疗、T细胞受体转导的T细胞治疗前期的试验结果已显示出这些免疫治疗方法的巨大效益.

随着食管癌诊断和治疗水平的不断进步, 不同角度不同层面对食管癌诊疗的报道逐渐增多, 为大家更深入的了解食管癌提供了有利条件. 如刘维华等系统的分析了MAGE-A在食管癌和食管癌细胞系中高度表达的状态, 并进一步说明MAGE-A基因编码的抗原肽可由食管癌细胞MHC Ⅰ类分子提呈至细胞毒性T细胞, 进而发挥特异性抗肿瘤活性.

本文针对食管癌免疫治疗的现状进行了系统的介绍, 通过现有的或正在进行的具体临床试验结果来说明免疫治疗在食管癌治疗中的应用情况, 并针对食管癌微环境的主要成分在肿瘤发生及治疗中的作用机制进行了评价. 较之前类似的文章更系统、具体、清晰, 对临床应用和研究有较好的借鉴作用.

在食管癌免疫治疗的临床应用分析的基础上提出免疫治疗与现有治疗模式的结合是今后食管癌治疗方向的观点, 并辅以具体试验的证据, 为食管癌免疫治疗在临床具体应用方案的制定提供了有力证据.

肿瘤微环境: 是指癌细胞周围的各种免疫细胞、成纤维细胞、内皮细胞、血管旁细胞、神经细胞、脂肪细胞及细胞外基质成分所构成的癌细胞发生发展的微观环境;

肿瘤免疫: 是指通过调节机体的免疫状态进而达到预防和治疗恶性肿瘤的一种治疗方法. 常见的治疗方法包括细胞因子、肿瘤疫苗、ACT和免疫检查点阻断剂等.

肖恩华, 教授, 中南大学湘雅二医院放射教研室; 李鹏, 教授, 首都医科大学附属北京友谊医院消化科

食管癌是消化系统最常见的恶性肿瘤之一, 本文系统评价了不同免疫疗法目前现状及发展的前景, 较全面论述免疫治疗在食管癌治疗中的巨大潜力. 认为采取免疫疗法与食管癌的传统治疗手段(内镜、手术、化疗和放疗)是今后食管癌治疗的方向. 信息量大, 比较新颖, 对临床应用和研究有较好的借鉴作用.

手稿来源: 邀请约稿

学科分类: 胃肠病学和肝病学

手稿来源地: 河南省

同行评议报告分类

A级 (优秀): 0

B级 (非常好): B

C级 (良好): C

D级 (一般): 0

E级 (差): 0

编辑:郭鹏 电编:胡珊

| 1. | Pennathur A, Gibson MK, Jobe BA, Luketich JD. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet. 2013;381:400-412. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Rustgi AK, El-Serag HB. Esophageal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2499-2509. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Chang S, Kohrt H, Maecker HT. Monitoring the immune competence of cancer patients to predict outcome. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63:713-719. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | van Vliet EP, Heijenbrok-Kal MH, Hunink MG, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Staging investigations for oesophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:547-557. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Ngamruengphong S, Wolfsen HC, Wallace MB. Survival of patients with superficial esophageal adenocarcinoma after endoscopic treatment vs surgery. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1424-1429.e2; quiz e81. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, Ang Y, Kang JY, Watson P, Trudgill N, Patel P, Kaye PV, Sanders S. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett's oesophagus. Gut. 2014;63:7-42. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Morgan MA, Lewis WG, Casbard A, Roberts SA, Adams R, Clark GW, Havard TJ, Crosby TD. Stage-for-stage comparison of definitive chemoradiotherapy, surgery alone and neoadjuvant chemotherapy for oesophageal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1300-1307. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BP, Richel DJ, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Hospers GA, Bonenkamp JJ. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2074-2084. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Tepper J, Krasna MJ, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Reed CE, Goldberg R, Kiel K, Willett C, Sugarbaker D, Mayer R. Phase III trial of trimodality therapy with cisplatin, fluorouracil, radiotherapy, and surgery compared with surgery alone for esophageal cancer: CALGB 9781. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1086-1092. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Malthaner R, Wong RK, Spithoff K. Preoperative or postoperative therapy for resectable oesophageal cancer: an updated practice guideline. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2010;22:250-256. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Sreedharan A, Harris K, Crellin A, Forman D, Everett SM. Interventions for dysphagia in oesophageal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD005048. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Zhu HD, Guo JH, Mao AW, Lv WF, Ji JS, Wang WH, Lv B, Yang RM, Wu W, Ni CF. Conventional stents versus stents loaded with (125)iodine seeds for the treatment of unresectable oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:612-619. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Dutton SJ, Ferry DR, Blazeby JM, Abbas H, Dahle-Smith A, Mansoor W, Thompson J, Harrison M, Chatterjee A, Falk S. Gefitinib for oesophageal cancer progressing after chemotherapy (COG): a phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:894-904. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Ford HE, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA, Janowitz T, Coxon FY, Wadsley J, Mansoor W, Fyfe D, Madhusudan S, Middleton GW. Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma (COUGAR-02): an open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:78-86. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, Lordick F, Ohtsu A, Omuro Y, Satoh T. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687-697. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2241-2252. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Pisani P, Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide mortality from 25 cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:18-29. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | Arnold M, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global incidence of oesophageal cancer by histological subtype in 2012. Gut. 2015;64:381-387. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Rubenstein JH, Shaheen NJ. Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:302-17.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Mathieu LN, Kanarek NF, Tsai HL, Rudin CM, Brock MV. Age and sex differences in the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Registry (1973-2008). Dis Esophagus. 2014;27:757-763. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Paget S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. 1889. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1989;8:98-101. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Sung SY, Hsieh CL, Wu D, Chung LW, Johnstone PA. Tumor microenvironment promotes cancer progression, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance. Curr Probl Cancer. 2007;31:36-100. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Sunpaweravong P, Sunpaweravong S, Puttawibul P, Mitarnun W, Zeng C, Barón AE, Franklin W, Said S, Varella-Garcia M. Epidermal growth factor receptor and cyclin D1 are independently amplified and overexpressed in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:111-119. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Hollstein MC, Metcalf RA, Welsh JA, Montesano R, Harris CC. Frequent mutation of the p53 gene in human esophageal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9958-9961. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Chung Y, Lam AK, Luk JM, Law S, Chan KW, Lee PY, Wong J. Altered E-cadherin expression and p120 catenin localization in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3260-3267. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Whiteside TL. The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene. 2008;27:5904-5912. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Waldron TJ, Quatromoni JG, Karakasheva TA, Singhal S, Rustgi AK. Myeloid derived suppressor cells: Targets for therapy. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e24117. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Jayaraman P, Parikh F, Lopez-Rivera E, Hailemichael Y, Clark A, Ma G, Cannan D, Ramacher M, Kato M, Overwijk WW. Tumor-expressed inducible nitric oxide synthase controls induction of functional myeloid-derived suppressor cells through modulation of vascular endothelial growth factor release. J Immunol. 2012;188:5365-5376. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Mazzoni A, Bronte V, Visintin A, Spitzer JH, Apolloni E, Serafini P, Zanovello P, Segal DM. Myeloid suppressor lines inhibit T cell responses by an NO-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2002;168:689-695. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 30. | Liu C, Yu S, Kappes J, Wang J, Grizzle WE, Zinn KR, Zhang HG. Expansion of spleen myeloid suppressor cells represses NK cell cytotoxicity in tumor-bearing host. Blood. 2007;109:4336-4342. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 31. | Srivastava MK, Sinha P, Clements VK, Rodriguez P, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells inhibit T-cell activation by depleting cystine and cysteine. Cancer Res. 2010;70:68-77. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Serafini P, Mgebroff S, Noonan K, Borrello I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote cross-tolerance in B-cell lymphoma by expanding regulatory T cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5439-5449. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 33. | Ha TY. The role of regulatory T cells in cancer. Immune Netw. 2009;9:209-235. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 34. | von Boehmer H, Daniel C. Therapeutic opportunities for manipulating T(Reg) cells in autoimmunity and cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:51-63. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 35. | Kono K, Kawaida H, Takahashi A, Sugai H, Mimura K, Miyagawa N, Omata H, Fujii H. CD4(+)CD25high regulatory T cells increase with tumor stage in patients with gastric and esophageal cancers. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:1064-1071. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 36. | Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, Evdemon-Hogan M, Conejo-Garcia JR, Zhang L, Burow M. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942-949. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 37. | Nabeki B, Ishigami S, Uchikado Y, Sasaki K, Kita Y, Okumura H, Arigami T, Kijima Y, Kurahara H, Maemura K. Interleukin-32 expression and Treg infiltration in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:2941-2947. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Xia M, Zhao MQ, Wu K, Lin XY, Liu Y, Qin YJ. Investigations on the clinical significance of FOXP3 protein expression in cervical oesophageal cancer and the number of FOXP3+ tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Int Med Res. 2013;41:1002-1008. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 39. | Osaki T, Saito H, Fukumoto Y, Yamada Y, Fukuda K, Tatebe S, Tsujitani S, Ikeguchi M. Inverse correlation between NKG2D expression on CD8+ T cells and the frequency of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:49-54. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 40. | Zou W, Restifo NP. T(H)17 cells in tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:248-256. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 41. | Bailey SR, Nelson MH, Himes RA, Li Z, Mehrotra S, Paulos CM. Th17 cells in cancer: the ultimate identity crisis. Front Immunol. 2014;5:276. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 42. | Oshima H, Oshima M. The inflammatory network in the gastrointestinal tumor microenvironment: lessons from mouse models. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:97-106. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 43. | Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1423-1437. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 44. | Colegio OR, Chu NQ, Szabo AL, Chu T, Rhebergen AM, Jairam V, Cyrus N, Brokowski CE, Eisenbarth SC, Phillips GM. Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature. 2014;513:559-563. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 45. | Ha SY, Yeo SY, Xuan YH, Kim SH. The prognostic significance of cancer-associated fibroblasts in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99955. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 46. | Chen Y, Li X, Yang H, Xia Y, Guo L, Wu X, He C, Lu Y. Expression of basic fibroblast growth factor, CD31, and α-smooth muscle actin and esophageal cancer recurrence after definitive chemoradiation. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:7275-7282. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 47. | Derks S, Nason KS, Liao X, Stachler MD, Liu KX, Liu JB, Sicinska E, Goldberg MS, Freeman GJ, Rodig SJ. Epithelial PD-L2 Expression Marks Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:1123-1129. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 48. | Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, Bourque K, Chernova T, Nishimura H, Fitz LJ, Malenkovich N, Okazaki T, Byrne MC. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1027-1034. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 49. | Ohigashi Y, Sho M, Yamada Y, Tsurui Y, Hamada K, Ikeda N, Mizuno T, Yoriki R, Kashizuka H, Yane K. Clinical significance of programmed death-1 ligand-1 and programmed death-1 ligand-2 expression in human esophageal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2947-2953. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 50. | Chen L, Deng H, Lu M, Xu B, Wang Q, Jiang J, Wu C. B7-H1 expression associates with tumor invasion and predicts patient's survival in human esophageal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:6015-6023. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443-2454. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 52. | Bierie B, Moses HL. Tumour microenvironment: TGFbeta: the molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:506-520. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 53. | Pickup M, Novitskiy S, Moses HL. The roles of TGFβ in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:788-799. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 54. | Song S, Maru DM, Ajani JA, Chan CH, Honjo S, Lin HK, Correa A, Hofstetter WL, Davila M, Stroehlein J. Loss of TGF-β adaptor β2SP activates notch signaling and SOX9 expression in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2159-2169. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 55. | Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392-401. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 56. | Sun X, Cheng G, Hao M, Zheng J, Zhou X, Zhang J, Taichman RS, Pienta KJ, Wang J. CXCL12/CXCR4/CXCR7 chemokine axis and cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:709-722. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 57. | Kaifi JT, Yekebas EF, Schurr P, Obonyo D, Wachowiak R, Busch P, Heinecke A, Pantel K, Izbicki JR. Tumor-cell homing to lymph nodes and bone marrow and CXCR4 expression in esophageal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1840-1847. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 58. | Liu J, Li F, Ping Y, Wang L, Chen X, Wang D, Cao L, Zhao S, Li B, Kalinski P. Local production of the chemokines CCL5 and CXCL10 attracts CD8+ T lymphocytes into esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:24978-24989. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 59. | Liu JY, Li F, Wang LP, Chen XF, Wang D, Cao L, Ping Y, Zhao S, Li B, Thorne SH. CTL- vs Treg lymphocyte-attracting chemokines, CCL4 and CCL20, are strong reciprocal predictive markers for survival of patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:747-755. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 60. | Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Carter SL, Stewart C, Mermel CH, Roberts SA. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499:214-218. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 61. | Meyer C, Cagnon L, Costa-Nunes CM, Baumgaertner P, Montandon N, Leyvraz L, Michielin O, Romano E, Speiser DE. Frequencies of circulating MDSC correlate with clinical outcome of melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63:247-257. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 62. | Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10:909-915. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 63. | Rosenberg SA, Sherry RM, Morton KE, Scharfman WJ, Yang JC, Topalian SL, Royal RE, Kammula U, Restifo NP, Hughes MS. Tumor progression can occur despite the induction of very high levels of self/tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in patients with melanoma. J Immunol. 2005;175:6169-6176. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 64. | Kono K, Mizukami Y, Daigo Y, Takano A, Masuda K, Yoshida K, Tsunoda T, Kawaguchi Y, Nakamura Y, Fujii H. Vaccination with multiple peptides derived from novel cancer-testis antigens can induce specific T-cell responses and clinical responses in advanced esophageal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1502-1509. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 65. | Kono K, Iinuma H, Akutsu Y, Tanaka H, Hayashi N, Uchikado Y, Noguchi T, Fujii H, Okinaka K, Fukushima R. Multicenter, phase II clinical trial of cancer vaccination for advanced esophageal cancer with three peptides derived from novel cancer-testis antigens. J Transl Med. 2012;10:141. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 66. | Saito T, Wada H, Yamasaki M, Miyata H, Nishikawa H, Sato E, Kageyama S, Shiku H, Mori M, Doki Y. High expression of MAGE-A4 and MHC class I antigens in tumor cells and induction of MAGE-A4 immune responses are prognostic markers of CHP-MAGE-A4 cancer vaccine. Vaccine. 2014;32:5901-5907. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 67. | Wada H, Sato E, Uenaka A, Isobe M, Kawabata R, Nakamura Y, Iwae S, Yonezawa K, Yamasaki M, Miyata H. Analysis of peripheral and local anti-tumor immune response in esophageal cancer patients after NY-ESO-1 protein vaccination. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2362-2369. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 68. | Dietrich A, Mitchison NA, Rajnavölgyi E, Schneider SC. Primed lymphocytes are boosted by type II collagen of their hosts after adoptive transfer. J Autoimmun. 1994;7:601-609. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 69. | Wang T, Mi Y, Pian L, Gao P, Xu H, Zheng Y, Xuan X. RNAi targeting CXCR4 inhibits proliferation and invasion of esophageal carcinoma cells. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:104. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 70. | Disis ML, Bernhard H, Jaffee EM. Use of tumour-responsive T cells as cancer treatment. Lancet. 2009;373:673-683. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 71. | Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Muul LM, Leitman S, Chang AE, Ettinghausen SE, Matory YL, Skibber JM, Shiloni E, Vetto JT. Observations on the systemic administration of autologous lymphokine-activated killer cells and recombinant interleukin-2 to patients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1485-1492. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 72. | Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, Restifo NP, Royal RE, Kammula U, White DE, Mavroukakis SA. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2346-2357. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 73. | Besser MJ, Shapira-Frommer R, Schachter J. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes: Clinical Experience. Cancer J. 2015;21:465-469. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 74. | Toh U, Yamana H, Sueyoshi S, Tanaka T, Niiya F, Katagiri K, Fujita H, Shirozou K, Itoh K. Locoregional cellular immunotherapy for patients with advanced esophageal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4663-4673. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Toh U, Sudo T, Kido K, Matono S, Sasahara H, Mine T, Tanaka T, Sueyoshi S, Fujita H, Shirouzu K. Locoregional adoptive immunotherapy resulted in regression in distant metastases of a recurrent esophageal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2002;7:372-375. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 76. | Bujas T, Marusic Z, Peric Balja M, Mijic A, Kruslin B, Tomas D. MAGE-A3/4 and NY-ESO-1 antigens expression in metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Histochem. 2011;55:e7. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 77. | Forghanifard MM, Gholamin M, Farshchian M, Moaven O, Memar B, Forghani MN, Dadkhah E, Naseh H, Moghbeli M, Raeisossadati R. Cancer-testis gene expression profiling in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: identification of specific tumor marker and potential targets for immunotherapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12:191-197. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 78. | Kageyama S, Wada H, Muro K, Niwa Y, Ueda S, Miyata H, Takiguchi S, Sugino SH, Miyahara Y, Ikeda H. Dose-dependent effects of NY-ESO-1 protein vaccine complexed with cholesteryl pullulan (CHP-NY-ESO-1) on immune responses and survival benefits of esophageal cancer patients. J Transl Med. 2013;11:246. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 79. | Kageyama S, Ikeda H, Miyahara Y, Imai N, Ishihara M, Saito K, Sugino S, Ueda S, Ishikawa T, Kokura S. Adoptive Transfer of MAGE-A4 T-cell Receptor Gene-Transduced Lymphocytes in Patients with Recurrent Esophageal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:2268-2277. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 80. | Gross G, Waks T, Eshhar Z. Expression of immunoglobulin-T-cell receptor chimeric molecules as functional receptors with antibody-type specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:10024-10028. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 81. | Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T Cells in Chronic Lymphoid Leukemia; Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T Cells for Acute Lymphoid Leukemia; Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for Sustained Remissions in Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:998. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 82. | Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, Chew A, Gonzalez VE, Zheng Z, Lacey SF. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1507-1517. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 83. | Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, Cui YK, Delbrook C, Feldman SA, Fry TJ, Orentas R, Sabatino M, Shah NN. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2015;385:517-528. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 84. | Porter DL, Hwang WT, Frey NV, Lacey SF, Shaw PA, Loren AW, Bagg A, Marcucci KT, Shen A, Gonzalez V. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells persist and induce sustained remissions in relapsed refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:303ra139. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 85. | Kershaw MH, Westwood JA, Parker LL, Wang G, Eshhar Z, Mavroukakis SA, White DE, Wunderlich JR, Canevari S, Rogers-Freezer L. A phase I study on adoptive immunotherapy using gene-modified T cells for ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6106-6115. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 86. | Ahmed N, Brawley VS, Hegde M, Robertson C, Ghazi A, Gerken C, Liu E, Dakhova O, Ashoori A, Corder A. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) -Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T Cells for the Immunotherapy of HER2-Positive Sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1688-1696. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 87. | Feng K, Guo Y, Dai H, Wang Y, Li X, Jia H, Han W. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for the immunotherapy of patients with EGFR-expressing advanced relapsed/refractory non-small cell lung cancer. Sci China Life Sci. 2016;59:468-479. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 88. | Rajagopal I, Niveditha SR, Sahadev R, Nagappa PK, Rajendra SG. HER 2 Expression in Gastric and Gastro-esophageal Junction (GEJ) Adenocarcinomas. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:EC06-EC10. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 89. | Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627-1639. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 90. | Larkin J, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1270-1271. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 91. | Huang H, Zhang G, Li G, Ma H, Zhang X. Circulating CD14(+)HLA-DR(-/low) myeloid-derived suppressor cell is an indicator of poor prognosis in patients with ESCC. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:7987-7996. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 92. | Goel G, Sun W. Advances in the management of gastrointestinal cancers--an upcoming role of immune checkpoint blockade. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:86. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 93. | Krummel MF, Allison JP. Pillars article: CD28 and CTLA-4 have opposing effects on the response of T cells to stimulation. The journal of experimental medicine. 1995. 182: 459-465. J Immunol. 2011;187:3459-3465. [PubMed] |

| 94. | Sakaguchi S, Fukuma K, Kuribayashi K, Masuda T. Organ-specific autoimmune diseases induced in mice by elimination of T cell subset. I. Evidence for the active participation of T cells in natural self-tolerance; deficit of a T cell subset as a possible cause of autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 1985;161:72-87. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 95. | Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057-1061. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 96. | Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711-723. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 97. | Calabrò L, Morra A, Fonsatti E, Cutaia O, Amato G, Giannarelli D, Di Giacomo AM, Danielli R, Altomonte M, Mutti L. Tremelimumab for patients with chemotherapy-resistant advanced malignant mesothelioma: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1104-1111. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 98. | Ralph C, Elkord E, Burt DJ, O'Dwyer JF, Austin EB, Stern PL, Hawkins RE, Thistlethwaite FC. Modulation of lymphocyte regulation for cancer therapy: a phase II trial of tremelimumab in advanced gastric and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1662-1672. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 99. | Lin T, Song C, Chuo DY, Zhang H, Zhao J. Clinical effects of autologous dendritic cells combined with cytokine-induced killer cells followed by chemotherapy in treating patients with advanced colorectal cancer: a prospective study. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:4367-4372. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 100. | Zhong R, Han B, Zhong H. A prospective study of the efficacy of a combination of autologous dendritic cells, cytokine-induced killer cells, and chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:987-994. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 101. | Yang L, Ren B, Li H, Yu J, Cao S, Hao X, Ren X. Enhanced antitumor effects of DC-activated CIKs to chemotherapy treatment in a single cohort of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:65-73. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 102. | Pusztai L, Karn T, Safonov A, Abu-Khalaf MM, Bianchini G. New Strategies in Breast Cancer: Immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:2105-2110. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 103. | Bobbio A, Alifano M. Immune therapy of non-small cell lung cancer. The future. Pharmacol Res. 2015;99:217-222. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 104. | Garnett CT, Palena C, Chakraborty M, Tsang KY, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Sublethal irradiation of human tumor cells modulates phenotype resulting in enhanced killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7985-7994. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 105. | Teitz-Tennenbaum S, Li Q, Okuyama R, Davis MA, Sun R, Whitfield J, Knibbs RN, Stoolman LM, Chang AE. Mechanisms involved in radiation enhancement of intratumoral dendritic cell therapy. J Immunother. 2008;31:345-358. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 106. | Ma JL, Jin L, Li YD, He CC, Guo XJ, Liu R, Yang YY, Han SX. The intensity of radiotherapy-elicited immune response is associated with esophageal cancer clearance. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014:794249. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 107. | Tesniere A, Schlemmer F, Boige V, Kepp O, Martins I, Ghiringhelli F, Aymeric L, Michaud M, Apetoh L, Barault L. Immunogenic death of colon cancer cells treated with oxaliplatin. Oncogene. 2010;29:482-491. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 108. | Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Abscopal but desirable: The contribution of immune responses to the efficacy of radiotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:407-408. [PubMed] [DOI] |