修回日期: 2013-01-11

接受日期: 2013-02-01

在线出版日期: 2013-02-28

目的: 探讨肠巨噬细胞髓系细胞触发受体-l(triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1, TREM-1)的表达对肠巨噬细胞侵袭力和肠上皮细胞增殖的影响, 进一步明确肠巨噬细胞在肠屏障功能障碍(intestinal barrier dysfunction, IBD)中可能的作用.

方法: 体外培养肠巨噬细胞及肠上皮细胞, 逆转录-多聚酶链反应(reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, RT-PCR)检测大鼠肠巨噬细胞的TREM-1和肿瘤坏死因子-α(tumor necrosis factor-α, TNF-α)基因表达水平, 用Tanswell板将二者共培养, MTT法绘制肠上皮细胞生长曲线, Matrigel侵袭实验检测肠巨噬细胞对肠上皮细胞的侵袭力.

结果: 脂多糖(lipopolysaccharide, LPS)组TREM-1及TNF-α的基因表达水平高于LPS+LP17组和空白对照(Control)组(均P<0.05); LPS+LP17组与Control组相比无差异. 与Control组相比, 两实验组的肠上皮细胞的生长均受到抑制(均P<0.05); LPS组肠上皮细胞生长的抑制大于LPS+LP17组(P<0.05). 侵袭实验中3组平均穿膜细胞数分别为29.3±2.1、46.0±3.6和34.7±3.1. LPS组与Control组比较差异具有明显统计学意义(P<0.01), LPS组与LPS+LP17组相比差异具有统计学意义(P<0.05).

结论: LP17不但能抑制肠巨噬细胞TREM-1的表达及炎症介质的释放, 还可以抑制肠巨噬细胞对上皮细胞的侵袭. 利用LP17阻断TREM-1信号转导可减轻肠巨噬细胞对肠上皮细胞的损害, 有望成为治疗IBD的新靶点.

引文著录: 张建新, 王坤, 祝文蕊, 沈耀, 王平江, 党胜春. 大鼠肠巨噬细胞TREM-l表达对其侵袭力和肠上皮细胞增殖的影响. 世界华人消化杂志 2013; 21(6): 471-477

Revised: January 11, 2013

Accepted: February 1, 2013

Published online: February 28, 2013

AIM: To explore the effect of TREM-1 expression in intestinal macrophages on their invasion and proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells to clarify the possible role of intestinal macrophages in the pathogenesis of intestinal barrier dysfunction (IBD).

METHODS: The expression levels of TREM-1 and TNF-α mRNAs in intestinal macrophages were determined by real-time PCR (RT-PCR) in vitro. After intestinal macrophages were co-cultured with intestinal epithelial cells in Transwell chamber, the growth curve of intestinal epithelial cells was determined by MTT assay. The matrigel invasion assay was used to detect the invasion of intestinal macrophages.

RESULTS: The expression levels of TREM-1 and TNF-α in the LPS group were significantly increased compared with the control group and LPS + LP17 group (both P < 0.05), but showed no significant difference between the control group and LPS + LP17 group (P > 0.05). Compared to the control group, the growth of intestinal epithelial cells was inhibited in the LPS group and LPS + LP17 group (both P < 0.05), and the inhibitory effect was more significant in the LPS group (P < 0.01). The average numbers of invading cells in the three groups were 29.3 ± 2.1, 46.0 ± 3.6, and 34.7 ± 3.1, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in the average number of invading cells between the LPS + LP17 group and LPS group (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: The expression of TREM-1 was inhibited by LP17 in intestinal macrophages, and TREM-1 expression inhibited the invasion of intestinal macrophages to intestinal epithelial cells. TREM-1 may be a new target for treatment of IBD.

- Citation: Zhang JX, Wang K, Zhu WR, Shen Y, Wang PJ, Dang SC. Effect of TREM-1 expression in intestinal macrophages on their invasion and proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2013; 21(6): 471-477

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v21/i6/471.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v21.i6.471

肠黏膜屏障是机体屏障系统的重要组成部分, 多种因素如炎症介质、氧化应激、微循环障碍、缺血再灌注损伤和细胞凋亡均可导致肠黏膜屏障损害[1,2]. 一旦黏膜屏障被破坏, 黏膜下层组织将暴露在肠腔复杂的抗原之中, 启动免疫反应, 产生大量细胞因子, 进一步加重肠黏膜损害[3]. 肠巨噬细胞主要分布在肠黏膜下的固有层中, 其总数占人体组织中巨噬细胞的绝大部分, 对维持肠屏障功能具有重要作用, 其活化可以产生大量肿瘤坏死因子-α(tumor necrosis factor-α, TNF-α)、白介素-6(interleukin-6, IL-6)等炎症介质, 形成级联反应, 导致细胞功能障碍, 引起肠屏障功能障碍(intestinal barrier dysfunction, IBD)[4]. 髓系细胞触发受体-l(triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1, TREM-1)主要在中性粒细胞和单核巨噬细胞上表达, 能诱导中性粒细胞和单核细胞分泌TNF-α等促炎因子[5-7]. 本文拟通过体外细胞实验, 探讨肠巨噬细胞对肠上皮细胞的影响, 进一步明确肠巨噬细胞在IBD中可能的作用.

1.1 材料SD健康大鼠, 体质量200-250 g, 由江苏大学实验动物中心提供; RPMI 1640培养基、FBS、Penicillin和Streptomycin购自Hyclone公司; 等渗细胞分离液(Percoll solution)购自Biosharp公司; 胶原酶Ⅳ购自Worthington公司; LP17多肽购自美国Invitrogen公司; MTT试剂盒购自碧云天公司; Tanswell板购自美国Corning公司.

1.2.1 肠巨噬细胞的分离: 大鼠麻醉后无菌解剖, 迅速取全肠. 用预冷PBS(pH 7.4)液冲洗肠腔, 纵向剖开, 置于含1 g/L EDTA的Hanks平衡盐溶液中, 37 ℃水浴振荡60 min. 弃上清, 用5 g/L胶原酶Ⅳ消化2 h, 所得细胞悬液400目筛网过滤. 再以Hanks液洗涤, 重悬于500 g/L等渗细胞分离液, 4 ℃ 2 000 r/min离心15 min, 收集细胞沉淀即为肠巨噬细胞, 以无钙、镁Hanks液洗涤3遍, 用台盼蓝染色, 细胞活力约为85%. 计数肠巨噬细胞, 以RPMI 1640培养基(10% FBS, 100 μg/mL Penicillin; 100 U/mL Streptomycin)调细胞浓度至5×l05/L.

1.2.2 肠上皮细胞的分离: 全肠置于含1 g/L EDTA的Hanks平衡盐溶液中, 37 ℃水浴振荡30 min. 收集上清, 用HBSS清洗2次, 悬于40%等渗的细胞分离液中. 4 ℃, 1 500 r/min离心15 min. 收集上层细胞(含有95%肠上皮细胞), 用HBSS洗3遍, 用台盼蓝染色, 细胞活力约为80%,以DMEM培养基(10%FBS; 20 ng/mL EGF; 5 μg/mL Insulin; 3.2 mmol/L Gutamine; 100 μg/mL Penicillin; 100 U/mL Streptomycin)调整细胞密度为1×l05个/mL. 细胞培养均置于37 ℃、50 mL/L CO2培养箱中培养.

1.2.3 分组: (1)空白对照(Control)组: 肠巨噬细胞不做处理; (2)脂多糖(lipopolysaccharide, LPS)组: 用LPS处理肠巨噬细胞, 培养液LPS终浓度为1 μg/mL; (3)LPS+LP17组: 用LPS及LP17联合处理肠巨噬细胞, 培养液LPS终浓度为1 μg/mL, LP17终浓度为100 ng/mL.

1.2.4 RT-PCR检测大鼠肠巨噬细胞TREM-1和TNF-α基因表达: 大鼠肠巨噬细胞分离后置于6孔板中培养, 每孔加入2 mL RPMI 1640培养液, 分组、给药, 培养6 h后提取总RNA. 分光光度计测定RNA样品在260 nm、280 nm的吸收值, 按RNA浓度 = (A260-A320)×稀释倍数×0.04 μg/μL计算RNA的浓度, A260/280等于1.8-2.0的RNA样品为纯度合格, 1.2%甲醛变性琼脂糖电泳检测RNA样品完整性. 再根据TransScript Reverse Transcriptase反转录试剂盒说明进行操作合成cDNA. TREM-1和TNF-α的RT-PCR引物由本室设计, 并由上海生工生物工程技术服务有限公司合成. TREM-1的mRNA引物序列为F: 5'-ACCCTGTTCTGCTCTTCC-3', R: 5'-AACCTCAGTCGGCTTTGT-3'; TNF-α的mRNA引物序列为F: 5'-AGGAGGAGAAGTTCCCAAAT-3', R: 5'-GCTACGGGCTTGTCACTC-3'. 以cDNA为模板, 以上述制备的cDNA为模板, 根据TransStart Top Green qPCR SurperMix说明书进行RT-PCR(25 μL反应体系). 以GAPDH为内参基因, 2-△△Ct法计算TREM-1和TNF-α的基因表达水平.

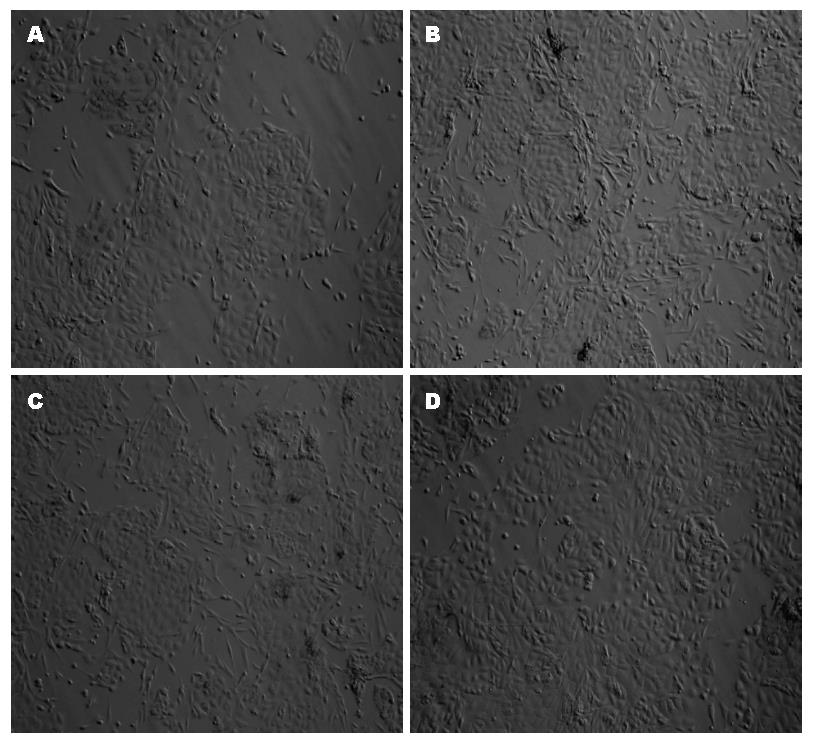

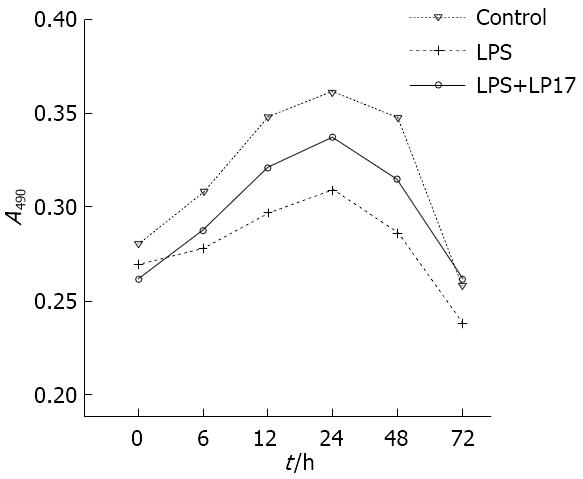

1.2.5 大鼠肠巨噬细胞和肠上皮细胞共培养: 将大鼠肠上皮细胞以1×l05个/mL的密度接种于24孔板(Transwell板)中, 每孔500 μL DMEM完全培养基; 再将大鼠肠巨噬细胞以5×l05个/mL的密度接种于24孔板的小室中, 每室500 μL RPMI 1640完全培养基, 将两种细胞共培养, 待细胞状态良好时对肠巨噬细胞进行分组给药(每组6个平行孔), 给药后共培养0、6、12、24、48、72 h后终止培养, 在酶联免疫检测仪上检测肠上皮细胞A490, 以时间为横坐标A490值为纵坐标作图, 根据检测值绘制肠上皮细胞生长曲线.

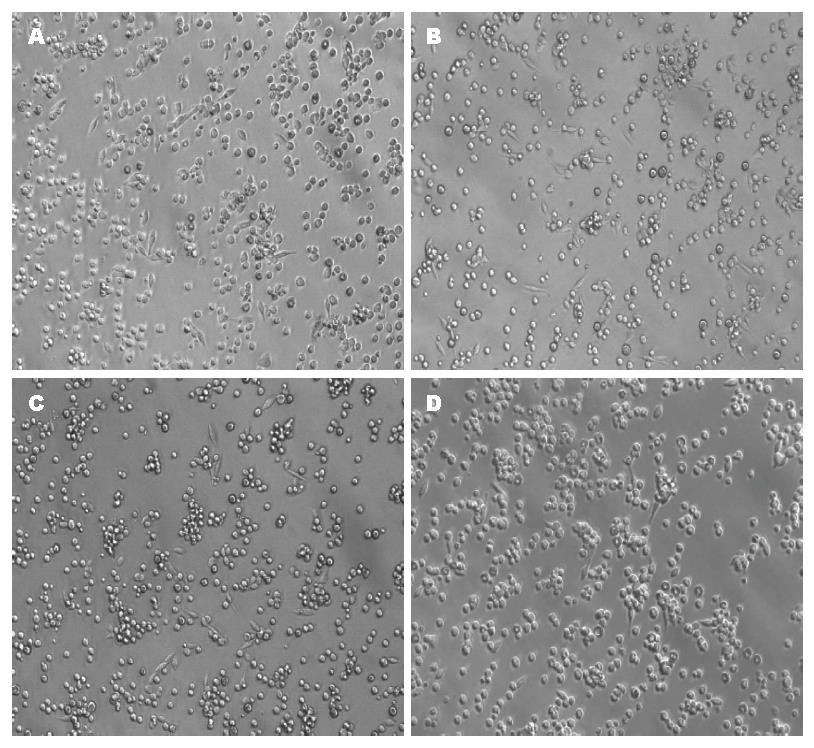

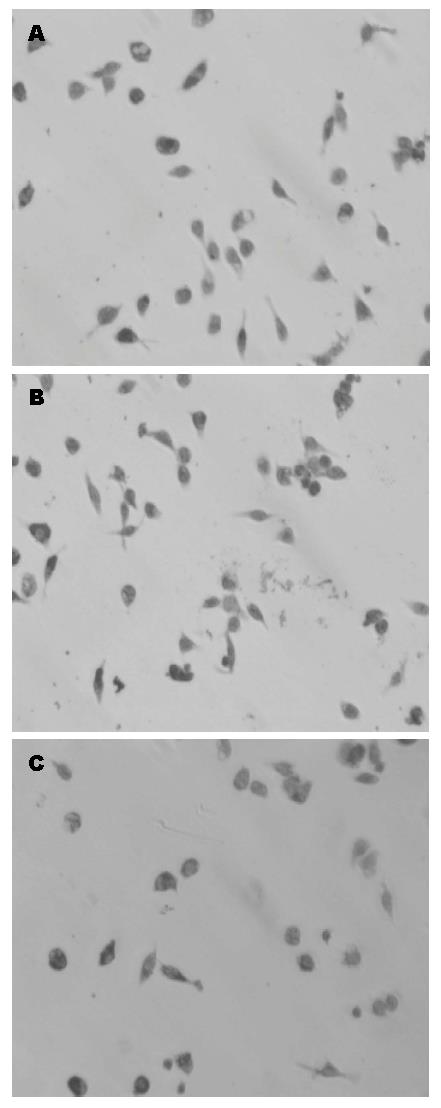

1.2.6 大鼠肠巨噬细胞基质胶侵袭实验: 取生长良好的肠巨噬细胞, RPMI 1640基础培养基轻洗两次; 加入无血清培养基, 37 ℃、50 mL/L CO2培养24 h, 收集细胞培养上清; 4 ℃, 12 000 r/min离心10 min, 取上清; 0.22 μm滤膜过滤除菌; 分装后于-20 ℃保存. 取出-20 ℃保存的Matrigel, 冰上过夜融化. 吸取100 μL Matrigel加入预冷的300 μL无血清培养基中, 充分混均. 取稀释好的Matrigel 50 μL加入Transwell板上室, 覆盖整个聚碳酯膜, 37 ℃静置30 min, 使Matrigel聚合成胶, 37 ℃可保存2 wk. 用PBS漂洗处理后的细胞3次. 0.25%胰酶消化, 终止消化后用RPMI 1640基础培养基制备单细胞悬液(5×105/mL), 每组细胞各分为两部分. 台盼蓝染色, 细胞活力>95%. Transwell培养板上室加入300 μL细胞悬液(5×104个). Transwell培养板下室加入500 μL趋化因子, 37 ℃、50 mL/L CO2培养24 h. 用湿棉签轻轻擦去Matrigel凝胶和聚碳酯膜上表面的细胞. 小心取出上室, 用线拴住, 做好标记, 用冰预冷的甲醇固定30 min. 苏木素染色1 min. 梯度乙醇脱水(80、95、100 mL/L), 二甲苯透明. 小心将聚碳酯膜自上室基底切取下来, 置载玻片上中性树脂封片. 附着于聚碳酯膜下表面的细胞在高倍镜下(×400)随机取3个视野计数, 取平均数.

统计学处理 利用SPSS17.0软件进行统计分析. 计量资料以mean±SD表示, 多组比较采用One-Way ANOVA, 两两比较采用SNK法检验. 以P<0.05为有统计学意义.

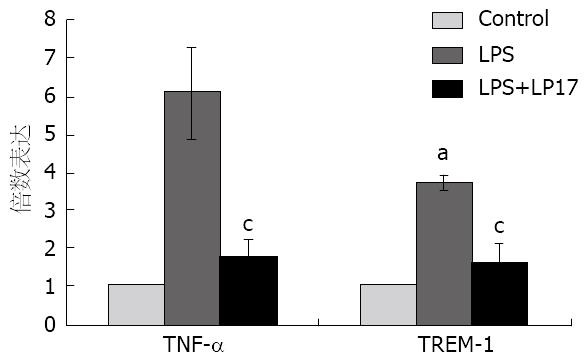

经LPS处理后肠巨噬细胞TREM-1的基因表达水平为3.71士0.18, TNF-α基因表达水平为6.09士1.20, 与Control组相比, 差异有统计学意义(P<0.05); 经LPS+LP17处理后肠巨噬细胞TREM-1基因表达水平为1.65士0.47, TNF-α基因表达水平为1.77士0.48, 与Control组相比, 无差异(P>0.05). LPS组与LPS+LP17组相比, 肠巨噬细胞TREM-1及TNF-α的基因表达水平均有差异(P<0.05, 图3).

与空白对照组相比, LPS组及LPS+LP17组肠上皮细胞的生长受到抑制(均P<0.05); 对LPS组肠上皮细胞生长的抑制大于LPS+LP17组(P<0.05, 图4).

TREM-1为免疫球蛋白超家族成员, 是主要表达于中性粒细胞和单核细胞表面的单次跨膜受体蛋白, 与配体结合后激活TREM-1信号通路, 在炎症级联放大反应和脓毒症发生发展中起重要作用[8,9]. TREM-1激活上调可触发多种炎症相关细胞因子如TNF-α、IL-6, 诱导中性粒细胞脱颗粒和单核巨噬细胞吞噬作用, 从而放大炎症反应[10]. 研究证实, TREM-1分子的活化需要其天然配体与Toll样受体家族(Toll-like receptors, TLR)配体的协同作用[11,12], 其中TLR4的配体LPS的作用最强[13,14]. TRL4受体活化后, 其效应蛋白如TNF-α及白细胞-1β(IL-1β)等又能明显上调TREM-1分子在细胞表面的表达[14]. TNF-α己被证实是炎症性肠病时引起肠黏膜屏障功能损伤的重要启动因子[15,16]. 临床研究表明炎症性肠病患者的TNF-α表达异常增高, 且表达水平与肠黏膜通透性相关,应用TNF-α抗体可以降低这些患者肠黏膜的通透性[17].

LP17多肽能减弱甚至阻断TREM-1信号通路的激活, 抑制炎症因子过度表达, 调节炎症反应[12]. 用LPS刺激小鼠脓毒症模型, 给小鼠注射LP17具有保护作用, 且其保护作用与LP17呈剂量相关性, 说明LP17可能有治疗脓毒症作用[18]. 最新研究表明LPl7能抑制SAP时血清sTREM-1的表达, 并显著减轻SAP引起的肝、肾功能障碍[19]. 本实验中利用RT-PCR检测肠巨噬细胞中TREM-1及TNF-α的基因表达水平, LPS组肠巨噬细胞培养6 h后TREM-1及TNF-α的mRNA表达水平比空白对照组明显升高, 且二者升高幅度呈正相关. 肠巨噬细胞经LPS+LP17处理后 TREM-1及TNF-α的mRNA表达水平比LPS组明显下降, TREM-1的基因表达下降更加明显, 但仍高于空白对照组. 结果显示LP17可以明显抑制LPS刺激肠巨噬细胞TREM-1及TNF-α的基因表达. 说明LP17可与肠巨噬细胞TREM-1配体竞争性结合, 抑制炎症因子过度表达. 提示干预肠巨噬细胞TREM-1表达可防治IBD.

肠上皮细胞间的紧密连接是由紧密连接蛋白构成, 主要包括闭锁蛋白、连接相关分子等跨膜蛋白和闭锁小带(zonula occludens, ZO)、丝状肌动蛋白(F-actin)等[20,21]. TNF-α可通过旁分泌形式作用于邻近肠上皮细胞, 一方面TNF-α可激活上皮细胞间的肌球蛋白轻链激酶, 调整紧密连接蛋白Occludin和ZO-1在紧密连接膜微区的分布, 造成紧密连接处功能障碍[22,23], 增加肠上皮细胞细胞旁的通透性, 是TNF-α引起肠黏膜屏障通透性增高的主要原因[24]; 另一方面TNF-α通过其受体TNFR1和/或TNFR2途径诱导肠上皮细胞凋亡[25,26], 使肠上皮细胞屏障同一位点上皮细胞脱落, 产生微小腐蚀点, 导致肠黏膜功能紊乱[27]. 肠上皮凋亡脱落进一步加剧肠黏膜通透性[28]. 另外, 在NF-κB介导下, TNF-α和INF-γ可上调肠上皮细胞内NOD2基因表达, 提高对LPS的敏感性[29], 从而加重炎症因子对肠上皮细胞的损害.

本文利用Transwell板将巨噬细胞与肠上皮细胞共培养的, 通过LP17及LPS处理肠巨噬细胞, 检测肠上皮细胞的活性及巨噬细胞的对肠上皮细胞的侵袭. 结果显示LPS刺激肠巨噬细胞释放的炎症因子, 可抑制肠上皮细胞的增殖, 利用LP17阻断TREM-1的表达可以减轻炎症因子对肠上皮细胞生长的抑制. 我们的实验还表明LP17可以减少肠巨噬细胞对肠上皮细胞的侵袭细胞数量, 说明LP17不但能抑制肠巨噬细胞TREM-1的表达, 还可以抑制固有层的肠巨噬细胞向黏膜层迁移, 减轻肠巨噬细胞分泌的炎症因子对肠上皮细胞的损害, 其机制可能与抑制肠巨噬细胞炎症因子的释放, 减弱炎症因子对巨噬细胞的趋化作用有关.

总之, 肠黏膜损伤是个相当复杂的过程, 涉及诸多因素与环节. 肠道细菌移位和炎症介质的过量释放是肠黏膜损伤的主要原因, TREM-1作为炎症放大介质有可能在肠黏膜屏障功能损害中起重要作用, 我们通过探讨肠巨噬细胞TREM-1的表达对肠上皮细胞增殖的影响及肠巨噬细胞对肠上皮细胞的侵袭, 说明利用LP17阻断TREM-1信号转导可减轻肠巨噬细胞对肠上皮细胞的损害, 有望成为治疗IBD的新靶点.

肠巨噬细胞对维持肠屏障功能具有重要作用, 其活化可以产生大量肿瘤坏死因子-α、白介素-6等炎症介质, 形成级联反应, 引起肠屏障功能障碍, 研究肠巨噬细胞在肠屏障功能中的作用具有重大意义.

庹必光, 教授, 遵义医学院附属医院消化科

从细胞及分子水平研究肠巨噬细胞髓系细胞触发受体-l(TREM-1)表达水平及其对肠黏膜的影响, 探讨TREM-l作为分子靶点治疗肠屏障功能障碍(IBD)的可行性.

由于肠道环境中存在较多的抗原类物质和各种微生物, 肠巨噬细胞在免疫表型和功能上有显著的特点. 结合肠巨噬细胞TREM-1变化在肠道免疫功能中发挥的独特作用, 利用TREM-1的特异性阻断剂干预其表达, 为TREM-1作为IBD分子治疗靶点的提供实验基础及理论依据.

本研究进一步明确肠巨噬细胞在IBD中可能的作用, 为治疗IBD提供实验基础及理论依据.

髓系细胞触发受体-l(TREM-1): 是主要表达于中性粒细胞和单核细胞表面的单次跨膜受体蛋白, 由V型Ig样胞外结构域、含有赖氨酸残基的跨膜结构域及缺乏信号基序的胞浆结构域3部分组成, 与NK细胞受体NKP44、白细胞受体MRF-3和多种免疫球蛋白受体有同源性.

本文有一定的科学及临床意义, 新颖性较好.

编辑: 李军亮 电编: 闫晋利

| 1. | Rahman SH, Ammori BJ, Holmfield J, Larvin M, McMahon MJ. Intestinal hypoperfusion contributes to gut barrier failure in severe acute pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:26-35; discussion 35-36. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Zhang XP, Zhang J, Song QL, Chen HQ. Mechanism of acute pancreatitis complicated with injury of intestinal mucosa barrier. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2007;8:888-895. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Fillon S, Robinson ZD, Colgan SP, Furuta GT. Epithelial function in eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29:171-178, xii-xiii. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | Leveau P, Wang X, Sun Z, Börjesson A, Andersson E, Andersson R. Severity of pancreatitis-associated gut barrier dysfunction is reduced following treatment with the PAF inhibitor lexipafant. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:1325-1331. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Washington AV, Quigley L, McVicar DW. Initial characterization of TREM-like transcript (TLT)-1: a putative inhibitory receptor within the TREM cluster. Blood. 2002;100:3822-3824. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Yoshioka N, Taniguchi Y, Yoshida A, Nakata K, Nishizawa T, Inagawa H, Kohchi C, Soma G. Intracellular localization of CD14 protein in intestinal macrophages. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:865-869. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Zhang JX, Dang SC, Qu JG, Wang XQ, Chen GZ. Changes of gastric and intestinal blood flow, serum phospholipase A2 and interleukin-1beta in rats with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3578-3581. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Gómez-Piña V, Soares-Schanoski A, Rodríguez-Rojas A, Del Fresno C, García F, Vallejo-Cremades MT, Fernández-Ruiz I, Arnalich F, Fuentes-Prior P, López-Collazo E. Metalloproteinases shed TREM-1 ectodomain from lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytes. J Immunol. 2007;179:4065-4073. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Liao R, Liu Z, Wei S, Xu F, Chen Z, Gong J. Triggering receptor in myeloid cells (TREM-1) specific expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of sepsis patients with acute cholangitis. Inflammation. 2009;32:182-190. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Bouchon A, Dietrich J, Colonna M. Cutting edge: inflammatory responses can be triggered by TREM-1, a novel receptor expressed on neutrophils and monocytes. J Immunol. 2000;164:4991-4995. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Wu M, Peng A, Sun M, Deng Q, Hazlett LD, Yuan J, Liu X, Gao Q, Feng L, He J. TREM-1 amplifies corneal inflammation after Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection by modulating Toll-like receptor signaling and Th1/Th2-type immune responses. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2709-2716. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Gibot S, Kolopp-Sarda MN, Béné MC, Bollaert PE, Lozniewski A, Mory F, Levy B, Faure GC. A soluble form of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 modulates the inflammatory response in murine sepsis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1419-1426. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Radsak MP, Salih HR, Rammensee HG, Schild H. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 in neutrophil inflammatory responses: differential regulation of activation and survival. J Immunol. 2004;172:4956-4963. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Bleharski JR, Kiessler V, Buonsanti C, Sieling PA, Stenger S, Colonna M, Modlin RL. A role for triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 in host defense during the early-induced and adaptive phases of the immune response. J Immunol. 2003;170:3812-3818. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W. Comparison of scheduled and episodic treatment strategies of infliximab in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:402-413. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Zeissig S, Bojarski C, Buergel N, Mankertz J, Zeitz M, Fromm M, Schulzke JD. Downregulation of epithelial apoptosis and barrier repair in active Crohn's disease by tumour necrosis factor alpha antibody treatment. Gut. 2004;53:1295-1302. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Suenaert P, Bulteel V, Lemmens L, Noman M, Geypens B, Van Assche G, Geboes K, Ceuppens JL, Rutgeerts P. Anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment restores the gut barrier in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2000-2004. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | Gibot S, Massin F, Alauzet C, Derive M, Montemont C, Collin S, Fremont S, Levy B. Effects of the TREM 1 pathway modulation during hemorrhagic shock in rats. Shock. 2009;32:633-637. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Kamei K, Yasuda T, Ueda T, Qiang F, Takeyama Y, Shiozaki H. Role of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 in experimental severe acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:305-312. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Ewert P, Aguilera S, Alliende C, Kwon YJ, Albornoz A, Molina C, Urzúa U, Quest AF, Olea N, Pérez P. Disruption of tight junction structure in salivary glands from Sjögren's syndrome patients is linked to proinflammatory cytokine exposure. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1280-1289. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Diesing AK, Nossol C, Panther P, Walk N, Post A, Kluess J, Kreutzmann P, Dänicke S, Rothkötter HJ, Kahlert S. Mycotoxin deoxynivalenol (DON) mediates biphasic cellular response in intestinal porcine epithelial cell lines IPEC-1 and IPEC-J2. Toxicol Lett. 2011;200:8-18. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Li Q, Zhang Q, Wang M, Zhao S, Ma J, Luo N, Li N, Li Y, Xu G, Li J. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha disrupt epithelial barrier function by altering lipid composition in membrane microdomains of tight junction. Clin Immunol. 2008;126:67-80. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Blikslager AT, Moeser AJ, Gookin JL, Jones SL, Odle J. Restoration of barrier function in injured intestinal mucosa. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:545-564. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Bruewer M, Luegering A, Kucharzik T, Parkos CA, Madara JL, Hopkins AM, Nusrat A. Proinflammatory cytokines disrupt epithelial barrier function by apoptosis-independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2003;171:6164-6172. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Piguet PF, Vesin C, Guo J, Donati Y, Barazzone C. TNF-induced enterocyte apoptosis in mice is mediated by the TNF receptor 1 and does not require p53. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3499-3505. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Babu D, Soenen SJ, Raemdonck K, Leclercq G, De Backer O, Motterlini R, Lefebvre RA. TNF-α/cycloheximide-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in murine intestinal epithelial MODE-K cells. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:4414-4425. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Kiesslich R, Duckworth CA, Moussata D, Gloeckner A, Lim LG, Goetz M, Pritchard DM, Galle PR, Neurath MF, Watson AJ. Local barrier dysfunction identified by confocal laser endomicroscopy predicts relapse in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2012;61:1146-1153. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Gitter AH, Bendfeldt K, Schulzke JD, Fromm M. Leaks in the epithelial barrier caused by spontaneous and TNF-alpha-induced single-cell apoptosis. FASEB J. 2000;14:1749-1753. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Rosenstiel P, Fantini M, Bräutigam K, Kühbacher T, Waetzig GH, Seegert D, Schreiber S. TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma regulate the expression of the NOD2 (CARD15) gene in human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1001-1009. [PubMed] [DOI] |