Published online Sep 21, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i35.5343

Peer-review started: May 8, 2020

First decision: June 8, 2020

Revised: June 15, 2020

Accepted: August 22, 2020

Article in press: August 22, 2020

Published online: September 21, 2020

Little is known about inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) burden and its impact on bone mineral density (BMD) among adult patients in Saudi Arabia. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the only study to give an update about this health problem in adult Saudi patients with IBD. IBD is a great risk factor for reduced BMD due to its associated chronic inflammation, malabsorption, weight loss and medication side effects. Consequently, screening for reduced BMD among patients with IBD is of utmost importance to curb and control anticipated morbidity and mortality among those patients.

To assess the relationship between IBD and BMD in a sample of adult Saudi patients with IBD.

Ninety adult patients with IBD - 62 Crohn’s disease (CD) and 28 ulcerative colitis (UC) - were recruited from King Fahad Specialist Hospital gastroenterology clinics in Buraidah, Al-Qassim. All enrolled patients were interviewed for their demographic information and for IBD- and BMD-related clinical data. All patients had the necessary laboratory markers and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scans to evaluate their BMD status. Patients were divided into two groups (CD and UC) to explore their clinical characteristics and possible risk factors for reduced BMD.

The CD group was significantly more prone to osteopenia and osteoporosis compared to the UC group; 44% of the CD patients had normal BMD, 19% had osteopenia, and 37% had osteoporosis, while 78% of the UC patients had normal BMD, 7% had osteopenia, and 25% had osteoporosis (P value < 0.05). In the CD group, the lowest t-score showed a statistically significant correlation with body mass index (BMI) (r = 0.45, P < 0.001), lumbar z-score (r = 0.77, P < 0.05) and femur z-score (r = 0.85, P < 0.05). In the UC group, the lowest t-score showed only statistically significant correlation with the lumbar z-score (r = 0.82, P < 0.05) and femur z-score (r = 0.80, P < 0.05). The ROC-curve showed that low BMI could predict the lowest t-score in the CD group with the best cut-off value at ≤ 23.43 (m/kg2); area under the curve was 0.73 (95%CI: 0.59–0.84), with a sensitivity of 77%, and a specificity of 63%.

Saudi patients with IBD still have an increased risk of reduced BMD, more in CD patients. Low BMI is a significant risk factor for reduced BMD in CD patients.

Core Tip: Saudi patients with inflammatory bowel disease still have a high prevalence of reduced bone mineral density. Osteopenia and osteoporosis burdens were 19% and 37% in Crohn’s disease (CD) patients, and 7% and 25% in ulcerative colitis patients, respectively. Low body mass index is a significant risk factor for reduced bone mineral density in CD patients.

- Citation: Ewid M, Al Mutiri N, Al Omar K, Shamsan AN, Rathore AA, Saquib N, Salaas A, Al Sarraj O, Nasri Y, Attal A, Tawfiq A, Sherif H. Updated bone mineral density status in Saudi patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(35): 5343-5353

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i35/5343.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i35.5343

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the main subtypes of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Europe and North America have the highest burden of CD and UC, approaching more than 0.3% of the population[1]. However, there has recently been an abrupt rise in the IBD burden in newly industrialized countries worldwide, including Asian countries. This rising trend is a result of multiple factors, including socioeconomic and lifestyle changes[2].

Data about the IBD prevalence in Saudi Arabia are very limited in the literature. However, similar to other Asian countries, Saudi Arabia has experienced lifestyle and industrialization changes over the past decades, with the available data pointing to increasing trends of both CD and UC in the eastern, western and central regions of Saudi Arabia[3].

IBD is not limited to the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). It also has extraintestinal manifestations that have been recorded in up to half of patients[4]. One of these manifestations is reduced bone mineral density (BMD), namely osteoporosis and osteopenia[5]. The literature shows that the burden of reduced BMD is increased among IBD patients, with a variable prevalence ranging from 5% to 37%[6].

Osteoporosis and osteopenia are well-known predictors of major health problems, including increased fracture risk, and consequently, decreased quality of life. IBD patients’ fracture risk is 40% higher than that recorded for non-IBD individuals[7]. Such increased fracture risk has severe implications for the health care system, with additional burden at the individual, social, and public levels[8]. Based on this added risk, screening for reduced BMD in IBD patients should be done on a regular basis to curb the anticipated morbidity and mortality of the disease.

Adding to the general risk factors for osteoporosis and osteopenia, IBD-specific factors include genetic predisposition, disease activity, medications (i.e., steroids), small bowel resection, malabsorption, low body mass index (BMI), and pro-inflammatory cytokines[9].

Little is known about the updated prevalence of reduced BMD and its predisposing factors among adult IBD patients in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, there is a knowledge gap regarding the impact of CD and UC on BMD among Saudi patients in the era of biological therapy. Consequently, our study aimed to investigate these knowledge gaps among IBD patients living in Al-Qassim province, Saudi Arabia.

This cross-sectional study took place at King Fahad Specialist Hospital in Buraidah, Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia between February 2018 and December 2019. The study was approved by the regional ethical committee, and all participants provided informed consent prior to their enrollment in the study.

Ninety adult (> 19 years old) Saudi patients with an IBD diagnosis (62 CD and 28 UC) were recruited from the hospital gastroenterology unit. The IBD diagnosis (either previously established or newly diagnosed) was based on patients’ clinical, endoscopic, radiographic, and histopathologic findings according to the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) diagnostic criteria[10,11].

IBD patients who had any concomitant malignancy, end organ failure, pregnancy, or a GIT pathology other than IBD were excluded from the study.

In their interview in the GIT department, patients received the standard of care according to the Saudi Ministry of Health guideline protocols regarding IBD (based on ECCO criteria), including history taking, physical examinations, investigations, and treatment plan. Moreover, all patients were offered the study questionnaire and given appointments to measure their BMD by dual x-ray energy absorptiometry (DXA) scan.

Clinical data: Clinical data were obtained by interviewing the patients and by reviewing their previous records and investigations. Data included age, gender, smoking status, BMI, physical activity, IBD-related extraintestinal manifestations (affecting the eye, skin, joints, liver, gall bladder and/or blood vessels)[12], IBD-related data (disease subtype, childhood onset, duration, extent, clinical presentations, perianal disease, malabsorption, hospital/ICU admissions, endoscopic reports, previous surgeries, and prescription drugs used), and IBD activity scores [Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) for CD[13] and Mayo Score for UC[14]].

Biochemical measurements: Following the patients’ initial interview, venous blood samples were obtained for their full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein, iron panel tests, liver and kidney function tests, calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and 25-hydroxy-vitamin D [25(OH)D]. Stool analysis was done for fecal calprotectin.

BMD measurements: We adopted the World Health Organization’s diagnostic criteria[15] for measuring BMD as follows: (1) Normal BMD: t-score ≥ -1 standard deviation (SD); (2) Osteopenia: t-score between -1.0 and -2.5 SD; and (3) Osteoporosis: t-score ≤ -2.5 SD.

Measurements were conducted on both lumbar spine and left femoral neck. BMD values were expressed as t- and z-scores[15]. We considered the lowest t-score values, obtained either from lumbar spine or femur neck, for BMD measurement. DXA scans were conducted using Discovery W, QDR series (Hologic, Waltham, MA, United States).

The statistical package of MedCalc version 19.0.5 was used in our analysis. Quantitative data is presented as mean ± SD, and qualitative data is presented as percentages. Comparisons between groups were made using the Mann-Whitney's u-test/unpaired t test for ordinal and continuous variables, respectively, and the χ2-test/Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables. Correlations between variables were performed using Pearson’s/Spearman's rank correlation coefficient when applicable. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Nazmus Saquib, PhD, from Sulaiman Al Rajhi University. He attests that the statistical methods in this study are suitable and adequately and appropriately described.

This cross-sectional study included 90 patients (31.5 ± 8.8, 19-60 years; 49 males, 54%). The patients were divided into 2 groups: CD group [62 patients (29.23 ± 7.58, 19-51 years; 32 males, 52%)], and UC group [28 patients (33.22 ± 10.53, 20-60 years; 17 males, 61%)].

Weight loss, malabsorption syndrome, abdominal pain, extraintestinal manifestations, previous related hospital admissions and previous related surgeries were higher, and BMI was lower in the CD group than in the UC group (Table 1).

| Parameters | CD (62 pts) | UC (28 pts) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 29.23 ± 7.58 | 33.22 ± 10.53 | NS |

| Sex (males), n (%) | 32 (52) | 17 (61) | NS |

| Smoking (%) | 10 | 29 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.2 ± 3.52 | 25.646 ± 2.87 | < 0.05 |

| Abdominal pain (%) | 83 | 17 | NS |

| Bloody diarrhea (%) | 67 | 96 | NS |

| Bleeding per rectum (%) | 3 | 4 | NS |

| Malabsorption syndrome (%) | 19 | 0 | < 0.05 |

| Perianal disease (%) | 59 | 4 | NS |

| Weight loss (%) | 11 | 0 | < 0.05 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations (%) | 21 | 7 | NS |

| Comorbidities (%) | 8 | 18 | NS |

| Previous IBD-related admission (n) | 2.16 ± 1.48 | 0.7 ± 0.44 | < 0.05 |

| Previous related surgeries (%) | 33 | 4 | NS |

| Family history (%) | 15 | 4 | NS |

| Steroid therapy (%) | 79 | 71 | NS |

| Azathioprine (%) | 82 | 37 | NS |

| Mesalamine (%) | 10 | 81 | < 0.05 |

| Anti-TNF therapy (%) | 65 | 29 | NS |

The disease in the CD group mainly affected the ilio-colicarea in 55% of the patients, 39% in the ileum, 3% in the colon, and the remaining 3% in the upper GIT. On the other hand, 50% of the UC group had left side colitis, 46% had pancolitis, and 4% had proctitis.

The CDAI score was 157.26 ± 98.15 (range: 27-490), and the Mayo score was 3.69 ± 2.27 (range: 1-11) in the CD and UC groups, respectively. There were more patients with severe clinical disease activity and endoscopic activity in the UC group than in the CD group (7 vs 3 patients).

Regarding medication history, the percentages of steroid, azathioprine, and anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) use were not significantly different between the CD group and the UC group. However, mesalamine use was significantly higher in the UC group.

Lab investigations showed that most of the variables were comparable between the two study groups. However, ALP, vitamin B12, and fecal calprotectin showed statistically significant higher values in the UC group than in the CD group (Table 2).

| Parameters | CD (62 pts) | UC (28 pts) | P value |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.41 ± 2.4 | 12.54 ± 2.58 | NS |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 6.7 ± 1.1 | 7.302 ± 3.6 | NS |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 333 ± 101 | 318 ± 121 | NS |

| ALT (U/L) | 13.61 ± 10.6 | 22.55 ± 28.48 | NS |

| AST (U/L) | 16.62 ± 8.38 | 20.69 ± 14.2 | NS |

| ALP (U/L) | 72.125 ± 29.02 | 84.434 ± 38.99 | < 0.05 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 36.335 ± 6.44 | 38.13 ± 6.98 | NS |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 60.81 ± 16.15 | 62.96 ± 16.6 | NS |

| Serum calcium (mmol/L) | 2.25 ± 0.17 | 2.23 ± 0.13 | NS |

| Phosphorus (µmol/L) | 1.17 ± 0.34 | 1.19 ± 0.18 | NS |

| PTT (s) | 29.53 ± 0.65 | 32.09 ± 7.58 | NS |

| PT (s) | 12.457 ± 2.65 | 12.71 ± 1.73 | NS |

| INR | 1.32 ± 74.48 | 1.11 ± 0.23 | NS |

| ESR (mm/h) | 22.67 ± 19.33 | 29.256 ± 31.87 | NS |

| CRP (> 3 mg/L) (%) | 21 | 17 | NS |

| Serum iron (µmol/L) | 8.16 ± 6.24 | 9.423 ± 7.39 | NS |

| TIBC (μg/dL) | 46.985 ± 13.52 | 58.19 ± 20.12 | NS |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 30.25 ± 12.03 | 32.34 ± 9.25 | NS |

| Serum vitamin D (ng/mL) | 12.09 ± 10.8 | 12.85 ± 4.21 | NS |

| Serum vitamin B12 (ng/mL) | 231.32 ± 182.34 | 314.67 ± 62.43 | < 0.05 |

| Fecal calprotectin (μg/mg) | 653 ± 265.13 | 1688.43 ± 426.79 | < 0.05 |

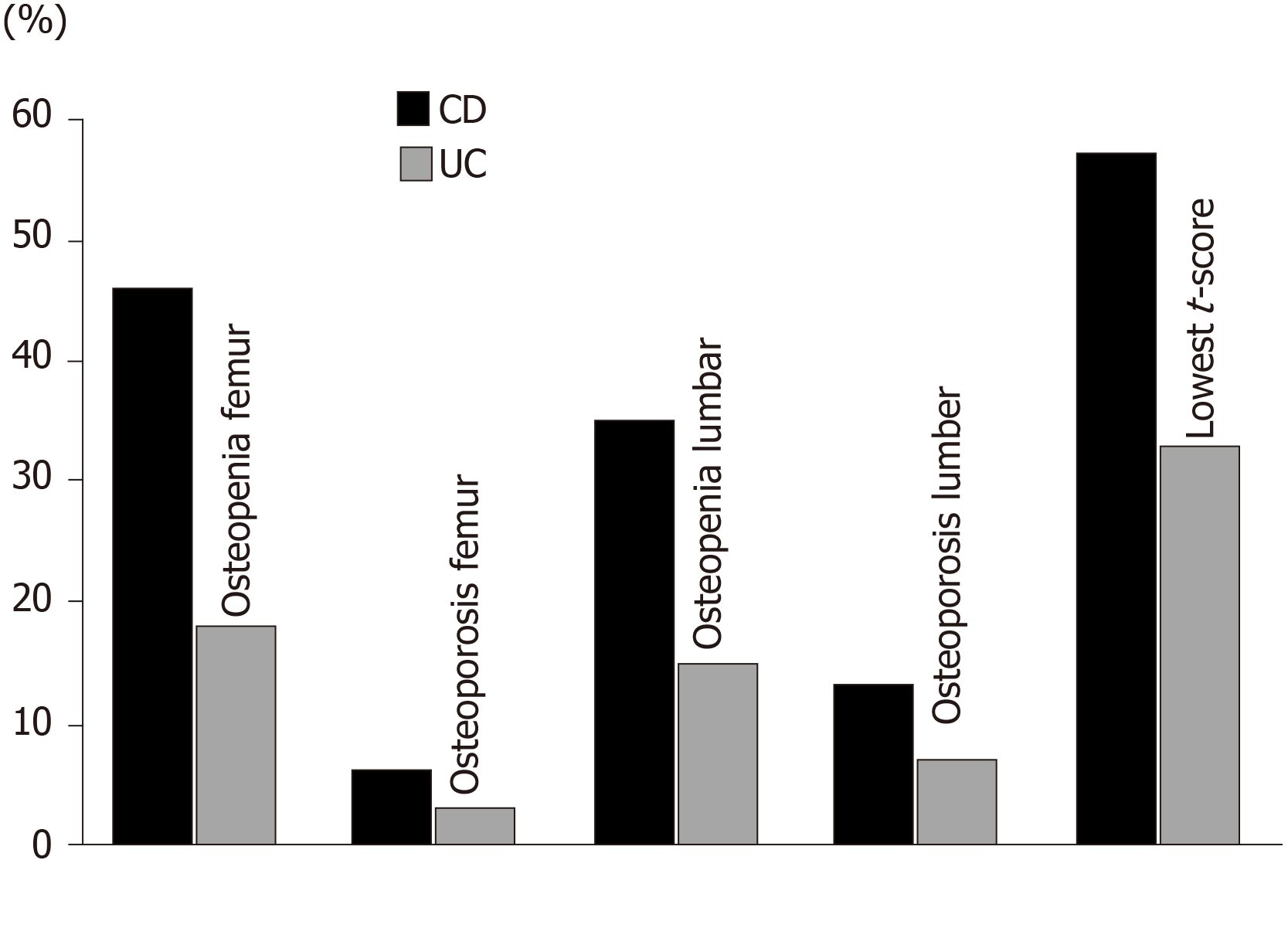

Out of all participants (both groups), 46 patients (51%) had normal t-scores (-0.27 ± 0.54) and 44 patients (49%) had low t-scores (-2.15 ± 0.77, P < 0.001). Lower BMD levels, and consequently higher osteopenia/osteoporosis percentages, were detected in the CD group than in the UC group. In the CD group, 44% of the patients had normal BMD, 19% had osteopenia, and 37% had osteoporosis, while in the UC group, 78% of the patients had normal BMD, 7% had osteopenia, and 25% had osteoporosis (P value < 0.05) (Table 3, Figure 1).

| Parameters | CD (62 pts) | UC (28 pts) | P value |

| Mean t-score femur | -0.94 ± 1.27 | -0.51 ± 0.9 | NS |

| Mean z-score femur | -0.67 ± 1.06 | -0.33 ± 0.82 | NS |

| Mean t-score lumbar | -0.97 ± 1.46 | -0.49 ± 1.27 | < 0.05 |

| Mean z-score lumbar | -0.45 ± 1.32 | -0.29 ± 1.26 | NS |

| Mean lowest t-score | -1.35 ± 0.91 | -0.84 ± 0.03 | < 0.05 |

| Osteopenia (%)1 | 37 | 25 | < 0.05 |

| Osteoporosis (%)1 | 19 | 7 | < 0.05 |

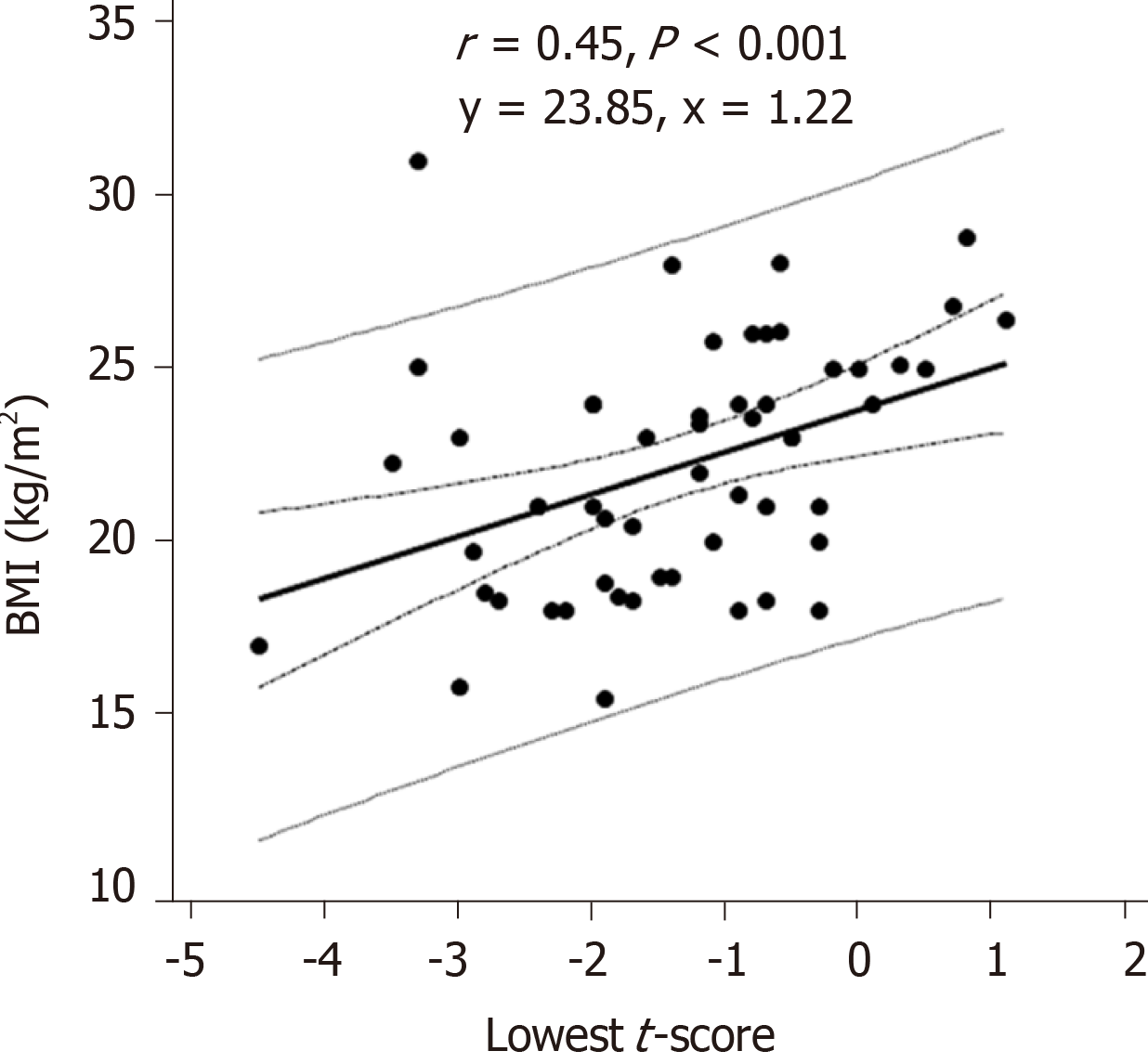

In the CD group, the lowest t-score showed a statistically significant correlation with BMI (r = 0.45, P < 0.001) (Figure 2), lumbar z-score (r = 0.77, P < 0.05) and femur z-score (r = 0.85, P < 0.05), but showed inverse correlations with abdominal pain (r = -0.35, P < 0.05), malabsorption syndrome (r = -0.44, P < 0.001), extraintestinal manifestations (r = -0.28, P < 0.05), total number of the symptoms (r = -0.29, P < 0.05) and with the need for vitamin D therapy (r = -0.27, P < 0.05).

In the UC group, the lowest t-score showed only statistically significant correlation with the lumbar z-score (r = 0.82, P < 0.05) and femur z-score (r = 0.80, P < 0.05).

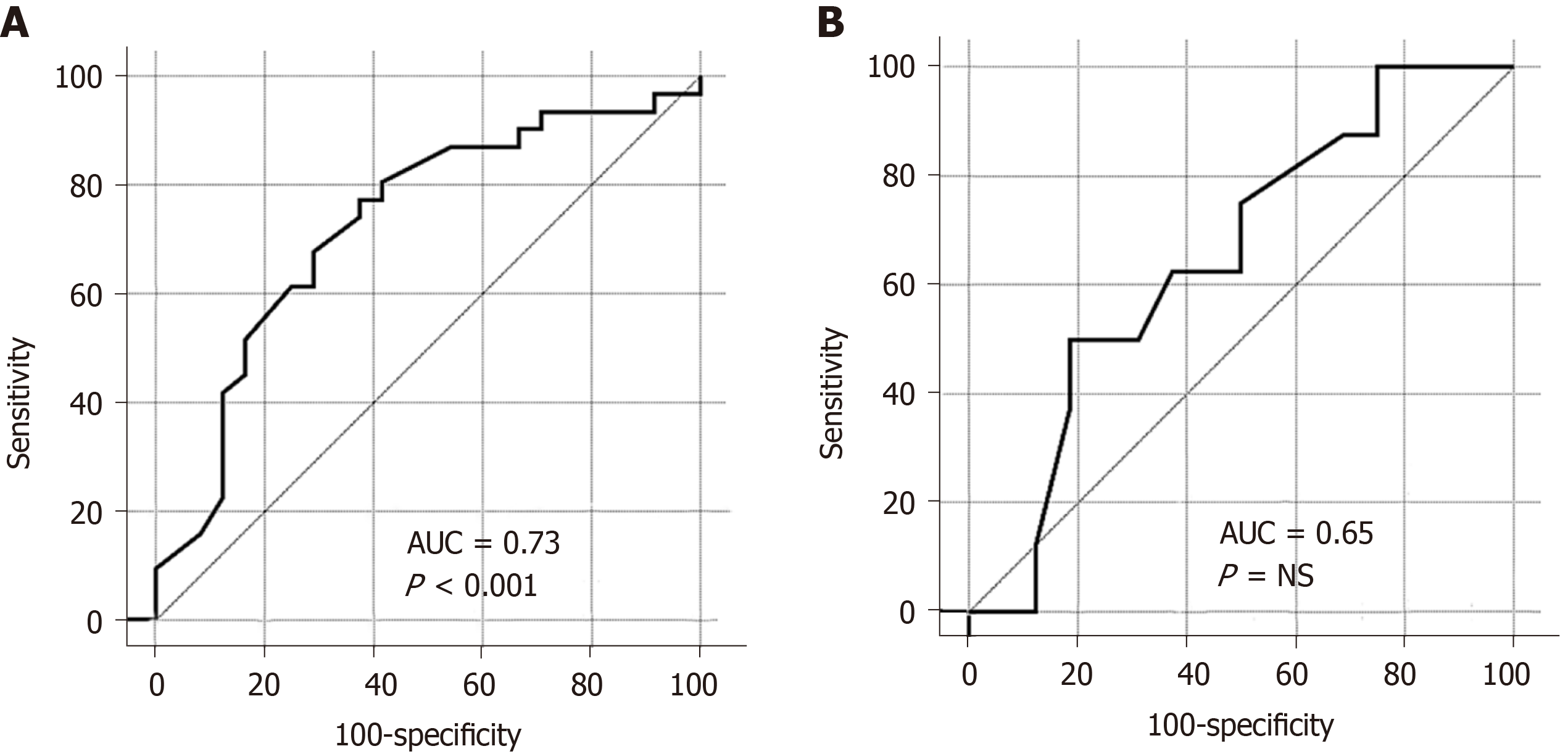

The ROC-curve showed that low BMI could predict low t-score much better in the CD rather than the UC group. In the CD group, the cut-off value was ≤ 23.43 (m/kg2); the area under the curve was 0.73 (95%CI: 0.59–0.84); the sensitivity was 77%, and the specificity was 63% (Figure 3A). In the UC group, the cut-off value was ≤ 23.5 (m/kg2); the area under the curve was 0.65 (95%CI: 0.43–0.83); the sensitivity was 50%, and the specificity was 81% (Figure 3B).

There was no significant difference in the lowest t-score between the CD and UC patients receiving anti-TNF-α therapy and those who did not receive it (Table 4).

| Groups | mean ± SD | 95%CI | P value | |

| CD group | ||||

| No anti-TNF-α | -1.10 ± 1.04 | -1.56 to -0.63 | 0.98 | |

| Anti-TNF-α | -1.48 ± 1.23 | -1.88 to -1.09 | ||

| UC group | ||||

| No anti-TNF-α | -0.74 ± 1.11 | -1.25 to -0.22 | 0.185 | |

| Anti-TNF-α | -1.10 ± 0.87 | -1.83 to -0.37 | ||

The main finding in our study is the relatively high percentage of undiagnosed reduced BMD: 56% among CD patients (37% osteopenia and 19% osteoporosis) and 32% among UC (25% osteopenia and 7% osteoporosis). Such high percentages of reduced BMD should alert us to an anticipated increase in fracture risk among Saudi patients with IBD. Hence, there is a need for proper screening programs to better control BMD loss and to ensure better quality of life for those patients.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first study to investigate this health problem in Al-Qassim province, Saudi Arabia. Moreover, it is the only study to provide updated data regarding BMD status among adult Saudi patients with IBD.

Based on our results, the burden of reduced BMD among adult Saudi patients with IBD is still high but is showing a decreasing trend compared to the results of a retrospective study conducted between 2001 and 2008 by Ismail et al[16] on 95 Saudi patients with IBD; osteopenia burden was 48.6% and 32.6%, and osteoporosis burden was 55.8% and 27.5% among CD and UC patients, respectively.

The relative improvement in BMD status in our study could be due to the improved standard of care, including increased use of biological therapies in our patients (53%), compared to the previously mentioned study, where the percentage of biological therapy use was 28%.

On the other hand, our results are still generally higher than those found in other Asian counties. In a study conducted by Wada et al[17] on 388 Japanese patients with IBD, they reported a prevalence of 40.4% osteopenia and 6.4% osteoporosis among CD patients, and 31.0% osteopenia and 4.3% osteoporosis among UC patients.

In a larger cohort study by Tsai et al[18] on the Asian population in Taiwan Province, the incidence of reduced BMD in IBD patients was 40% more than that in non-IBD participants. Moreover, the study showed an osteoporosis incidence rate of 7.3% in CD patients and 6.3% in UC patients, which is comparable to the above-mentioned Japanese study but is much lower than that found in our study. On the other hand, the prevalence among Western populations was initially investigated by Schulte et al[19] on German participants and concluded the following ranges: 32% to 36% for osteopenia and 7% to 15% for osteoporosis. Similar findings were later mentioned by Sheth et al[20] Most of the reports that estimated the fracture risk among IBD patients were based on Western populations as highlighted by Szafors et al[21] in their systematic review, with an overall 38% higher fracture risk in IBD patients compared to the controls.

The different findings among IBD studies regarding BMD prevalence (including those related to IBD subtypes CD and UC) could be attributed to either variability in research methodology (study design and sample size) or variability in patients’ characteristics, including ethnicity, age, gender, IBD severity, nutritional status and quality of health care settings. For example, we conducted our study in the largest central tertiary care hospital in the region, which usually manages advanced cases of complicated disease that need a high level of care. Accordingly, there is a possibility that this setting could partly explain the high prevalence of both osteopenia and osteoporosis in our sample as compared to other studies.

Another important finding in our study is that CD patients were at higher risk of developing both osteoporosis and osteopenia than UC patients, a finding that mirrors previously published data[18,22,23]. This risk could be explained by more chronic inflammation (indicated by higher hospital admissions and biological therapy use and lower BMI) in CD patients than in UC patients. On the other hand, there are other studies that did not show any epidemiological BMD difference between CD and UC patients[24].

The prevalence of CD (69%) was higher than UC (31%) in our sample, a finding that is consistent with previous epidemiological studies in Saudi Arabia[25,26]. Taking into consideration the increasing trend of CD patients in Saudi Arabia, who are at higher risk for reduced BMD than UC patients, health care providers should anticipate more burden of osteoporosis and osteopenia among those patients and take the necessary preventive and screening actions.

It is speculated that the cornerstone pathogenic factor of reduced BMD among IBD patients is chronic inflammation that is induced by pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines, including interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6 and TNF-α. These pro-inflammatory mediators disturb the physiologic bone remodeling process through an imbalance of osteoprotegerin, receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B (RANK), and the RANK ligand (RANKL) pathway. When there is a decrease in osteoprotegerin, a decoy receptor that limits RANKL-RANK interaction, it activates osteoclast, which is responsible for bone resorption[27,28].

The third main finding in our study is that low BMI was a risk factor for reduced BMD, which matches data from previous studies[17,29,30]. This finding was more evident in CD patients than in UC patients; BMI could predict the severity of reduced BMD with a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 63%, AUC 0.73 (95%CI: 0.59–0.84) in the CD group.

An unexpected finding in our study and in previous studies is the lack of correlation between steroid use and BMD[6,22,31,32]. For our study, this result may be due to the lack of a registry to precisely record our patients’ steroid therapy details. Intake of prednisolone > 7.5 mg/d for 3 mo is an established risk for developing osteoporosis[33], as shown in previous studies[17,27,30].

It is known that patients with IBD requiring biological therapy have the most severe inflammation and a greater anticipated decrease in their BMD than other IBD patients[34]. Our study, in contrast, did not find any significant difference in BMD between the CD and UC patients receiving anti-TNF-α therapy and those not receiving it (P value = 0.980 and 0.185, respectively). This finding could spotlight the beneficial role of biological therapy for BMD in IBD patients, but it needs further clarification in future studies.

The cross-sectional nature of the study precluded us from conducting a follow-up of reduced BMD risk factors in our patients. Moreover, our study is a single-center study, and it may be better to conduct a study in all health care centers in the province in order to enroll a diverse spectrum of IBD patients and increase the sample size.

Adult Saudi patients with IBD, although better than before, still have higher reduced BMD than Eastern Asian countries, with a significantly higher risk among CD patients compared to UC patients. Low BMI was a significant risk factor for reduced BMD in the CD group. We recommend further prospective multicenter studies among adult Saudi patients with IBD for a better assessment of reduced BMD risk factors and to investigate the current DXA screening practices among those patients.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is showing an increasing trend in newly industrialized countries worldwide, including Saudi Arabia. Reduced bone mineral density (BMD) is a major documented extraintestinal complication in patients with IBD. As with other IBD patients, Saudi patients with IBD will have increased fracture risk and lower quality of life if not properly screened for reduced BMD.

Little is known about how much reduced BMD occurs among Saudi patients with IBD or about the predisposing factors in that population. Our study gives an update about reduced BMD among adult Saudi patients with IBD. We hope it will help health care providers curb the anticipated complications through proper preventive and screening measures.

We aimed to assess the current burden of reduced BMD and its possible risk factors among adult Saudi patients with IBD. Moreover, we investigated any possible variations between Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) patients, either in the disease burden or its related risk factors.

Ninety adult patients with IBD - 62 CD and 28 UC - were recruited from King Fahad Specialist Hospital gastroenterology clinics in the city of Buraidah, Saudi Arabia. Demographics, clinical workups and dual x-ray energy absorptiometry (DXA) scan data were obtained. Patients were divided into two groups (CD and UC) to explore their clinical characteristics and possible risk factors for reduced BMD. Appropriate statistical tests were used according to the variables. A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Patients with CD were at higher risk for reduced BMD than those with UC; 19% of CD patients had osteopenia, and 37% had osteoporosis, while among the UC patients, 7% had osteopenia, and 25% had osteoporosis (P value < 0.05). In the CD group, the lowest t-score showed a statistically significant correlation with body mass index (BMI) (r = 0.45, P < 0.001), best cut-off value at ≤ 23.43 (m/kg2); area under the curve was 0.73 (95%CI: 0.59–0.84). In the UC group, the lowest t-score showed only statistically significant correlation with the lumbar z-score (r = 0.82, P < 0.05) and femur z-score (r = 0.80, P < 0.05).

There is still an increased risk of reduced BMD for Saudi patients with IBD, more so in CD patients. Low BMI is a significant risk factor for reduced BMD in CD patients.

We recommend further prospective multicenter studies among adult Saudi patients with IBD for a better assessment of reduced BMD risk factors and to investigate the current DXA screening practices among those patients.

The authors thank Ms. Erin Strotheide for her editorial contributions to this manuscript.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Saudi Arabia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sassaki LY S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2018;390:2769-2778. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2677] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3170] [Article Influence: 452.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and Preventing the Global Increase of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:313-321.e2. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 566] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 645] [Article Influence: 92.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | El Mouzan MI, AlEdreesi MH, Hasosah MY, Al-Hussaini AA, Al Sarkhy AA, Assiri AA. Regional variation of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Saudi Arabia: Results from a multicenter study. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:416-423. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N. The prevalence of extraintestinal diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1116-1122. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 475] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bjarnason I, Macpherson A, Mackintosh C, Buxton-Thomas M, Forgacs I, Moniz C. Reduced bone density in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1997;40:228-233. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 277] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lo B, Holm JP, Vester-Andersen MK, Bendtsen F, Vind I, Burisch J. Incidence, Risk Factors and Evaluation of Osteoporosis in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Danish Population-Based Inception Cohort With 10 Years of Follow-Up. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:904-914. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Leslie W, Wajda A, Yu BN. The incidence of fracture among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. A population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:795-799. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 356] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Viswanathan M, Reddy S, Berkman N, Cullen K, Middleton JC, Nicholson WK, Kahwati LC. Screening to Prevent Osteoporotic Fractures: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319:2532-2551. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rodríguez-Bores L, Barahona-Garrido J, Yamamoto-Furusho JK. Basic and clinical aspects of osteoporosis in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6156-6165. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, Ardizzone S, Armuzzi A, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Burisch J, Gecse KB, Hart AL, Hindryckx P, Langner C, Limdi JK, Pellino G, Zagó,rowicz E, Raine T, Harbord M, Rieder F, European Crohn’,s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 1: Definitions, Diagnosis, Extra-intestinal Manifestations, Pregnancy, Cancer Surveillance, Surgery, and Ileo-anal Pouch Disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649-670. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1024] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1094] [Article Influence: 156.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gionchetti P, Dignass A, Danese S, Magro Dias FJ, Rogler G, Lakatos PL, Adamina M, Ardizzone S, Buskens CJ, Sebastian S, Laureti S, Sampietro GM, Vucelic B, van der Woude CJ, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Maaser C, Portela F, Vavricka SR, Gomollón F; ECCO. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn's Disease 2016: Part 2: Surgical Management and Special Situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:135-149. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 451] [Article Influence: 64.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hedin CRH, Vavricka SR, Stagg AJ, Schoepfer A, Raine T, Puig L, Pleyer U, Navarini A, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Maul J, Katsanos K, Kagramanova A, Greuter T, González-Lama Y, van Gaalen F, Ellul P, Burisch J, Bettenworth D, Becker MD, Bamias G, Rieder F. The Pathogenesis of Extraintestinal Manifestations: Implications for IBD Research, Diagnosis, and Therapy. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:541-554. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Winship DH, Summers RW, Singleton JW, Best WR, Becktel JM, Lenk LF, Kern F. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study: study design and conduct of the study. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:829-842. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | D'Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Geboes K, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, Lémann M, Marteau P, Rutgeerts P, Schölmerich J, Sutherland LR. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:763-786. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 721] [Article Influence: 42.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | World Health Organization. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: Report of a WHO study group; 1992 June 22-25; Rome, Italy. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39142. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Ismail MH, Al-Elq AH, Al-Jarodi ME, Azzam NA, Aljebreen AM, Al-Momen SA, Bseiso BF, Al-Mulhim FA, Alquorain A. Frequency of low bone mineral density in Saudi patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:201-207. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wada Y, Hisamatsu T, Naganuma M, Matsuoka K, Okamoto S, Inoue N, Yajima T, Kouyama K, Iwao Y, Ogata H, Hibi T, Abe T, Kanai T. Risk factors for decreased bone mineral density in inflammatory bowel disease: A cross-sectional study. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:1202-1209. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tsai MS, Lin CL, Tu YK, Lee PH, Kao CH. Risks and predictors of osteoporosis in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases in an Asian population: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69:235-241. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schulte C, Dignass AU, Mann K, Goebell H. Reduced bone mineral density and unbalanced bone metabolism in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1998;4:268-275. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sheth T, Pitchumoni CS, Das KM. Musculoskeletal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease: a revisit in search of immunopathophysiological mechanisms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:308-317. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Szafors P, Che H, Barnetche T, Morel J, Gaujoux-Viala C, Combe B, Lukas C. Risk of fracture and low bone mineral density in adults with inflammatory bowel diseases. A systematic literature review with meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29:2389-2397. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jahnsen J, Falch JA, Aadland E, Mowinckel P. Bone mineral density is reduced in patients with Crohn's disease but not in patients with ulcerative colitis: a population based study. Gut. 1997;40:313-319. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 208] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L. Fracture risk in patients with celiac Disease, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis: a nationwide follow-up study of 16,416 patients in Denmark. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:1-10. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 231] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vázquez MA, Lopez E, Montoya MJ, Giner M, Pérez-Temprano R, Pérez-Cano R. Vertebral fractures in patients with inflammatory bowel disease compared with a healthy population: a prospective case-control study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:47. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fadda MA, Peedikayil MC, Kagevi I, Kahtani KA, Ben AA, Al HI, Sohaibani FA, Quaiz MA, Abdulla M, Khan MQ, Helmy A. Inflammatory bowel disease in Saudi Arabia: a hospital-based clinical study of 312 patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:276-282. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Al-Mofarreh MA, Al-Mofleh IA. Emerging inflammatory bowel disease in saudi outpatients: a report of 693 cases. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:16-22. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Agrawal M, Arora S, Li J, Rahmani R, Sun L, Steinlauf AF, Mechanick JI, Zaidi M. Bone, inflammation, and inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2011;9:251-257. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lacey DL, Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Kostenuik PJ, Dougall WC, Sullivan JK, San Martin J, Dansey R. Bench to bedside: elucidation of the OPG-RANK-RANKL pathway and the development of denosumab. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:401-419. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 444] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Jahnsen J, Falch JA, Mowinckel P, Aadland E. Bone mineral density in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based prospective two-year follow-up study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:145-153. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Azzopardi N, Ellul P. Risk factors for osteoporosis in Crohn's disease: infliximab, corticosteroids, body mass index, and age of onset. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1173-1178. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Leslie WD, Miller N, Rogala L, Bernstein CN. Body mass and composition affect bone density in recently diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease: the Manitoba IBD Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:39-46. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Naito T, Yokoyama N, Kakuta Y, Ueno K, Kawai Y, Onodera M, Moroi R, Kuroha M, Kanazawa Y, Kimura T, Shiga H, Endo K, Nagasaki M, Masamune A, Kinouchi Y, Shimosegawa T. Clinical and genetic risk factors for decreased bone mineral density in Japanese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:1873-1881. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Suzuki Y, Nawata H, Soen S, Fujiwara S, Nakayama H, Tanaka I, Ozono K, Sagawa A, Takayanagi R, Tanaka H, Miki T, Masunari N, Tanaka Y. Guidelines on the management and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis of the Japanese Society for Bone and Mineral Research: 2014 update. J Bone Miner Metab. 2014;32:337-350. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 115] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Terdiman JP, Gruss CB, Heidelbaugh JJ, Sultan S, Falck-Ytter YT; AGA Institute Clinical Practice and Quality Management Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the use of thiopurines, methotrexate, and anti-TNF-α biologic drugs for the induction and maintenance of remission in inflammatory Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1459-1463. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 175] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |