Published online Dec 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i47.10432

Peer-review started: August 11, 2016

First decision: September 5, 2016

Revised: September 25, 2016

Accepted: October 31, 2016

Article in press: October 31, 2016

Published online: December 21, 2016

To evaluate the real-world effectiveness of golimumab in ulcerative colitis (UC) and to identify predictors of response.

We conducted an observational, prospective and multi-center study in UC patients treated with golimumab, from September 2014 to September 2015. Clinical activity was assessed at week 0 and 14 with the physician’s global clinical assessment (PGA) and the partial Mayo score. Colonoscopies and blood tests were performed, following daily-practice clinical criteria, and the results were recorded in an SPSS database.

Thirty-three consecutive patients with moderately to severely active UC were included. Among them, 54.5% were female and 42 years was the average age. Thirty percent had left-sided UC (E2) and 70% had extensive UC (E3). All patients had an endoscopic Mayo score of 2 or 3 at baseline. Twenty-seven point three percent were anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) treatment naïve, whereas 72.7% had previously received infliximab and/or adalimumab. Sixty-nine point seven percent showed clinical response and were steroid-free at week 14 (a decrease from baseline in the partial Mayo score of at least 3 points). Based on PGA, the clinical remission and clinical response rates were 24% and 55% respectively. Withdrawal of corticosteroids was observed in 70.8% of steroid-dependent patients at the end of the study. Three out of 10 clinical non-responders needed a colectomy. Mean fecal calprotectin value at baseline was 300 μg/g, and 170.5 μg/g at week 14. Being anti-TNF treatment naïve was a protection factor, which was related to better chances of reaching clinical remission. Twenty-seven point three percent of the patients required treatment intensification at 14 wk of follow-up. Only three adverse effects (AEs) were observed during the study; all were mild and golimumab was not interrupted.

This real-life practice study endorses golimumab’s promising results, demonstrating its short-term effectiveness and confirming it as a safe drug during the induction phase.

Core tip: Golimumab is a fully humanized anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha monoclonal antibody, which has recently been accepted in clinical practice. Pivotal studies have demonstrated the drug’s benefits, but real-life studies are still scarce. This observational, prospective and multi-center study in moderate-severe ulcerative colitis patients, confirmed golimumab’s short-term (14 wk) effectiveness. A high percentage of patients had responded and were off steroids at the end of follow-up. No severe adverse events were observed. Intensification (reducing the drug administration interval or increasing the dosage) may be useful in many slow-to-respond cases.

- Citation: Bosca-Watts MM, Cortes X, Iborra M, Huguet JM, Sempere L, Garcia G, Gil R, Garcia M, Muñoz M, Almela P, Maroto N, Paredes JM. Short-term effectiveness of golimumab for ulcerative colitis: Observational multicenter study. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(47): 10432-10439

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i47/10432.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i47.10432

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of the colon, with progressively increasing incidence and prevalence. The prevalence of UC varies by geographic region, ranging from 4.9 to 505 per 100000 people in Europe, 4.9 to 168.3 per 100000 in Asia and the Middle East, and 37.5 to 248.6 per 100000 in North America[1-6]. The treatment of UC was initially based on symptom improvement and induction of clinical remission, but has become more ambitious as new treatments have appeared. Nowadays, the objective is to maintain a steroid-free remission, prevent hospital admission and surgery, obtain mucosal healing, improve quality of life and avoid disability[2]. Treatment for UC consists mainly of mesalazine, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs and biologic drugs (monoclonal antibodies to tumor necrosis factor-alpha (anti-TNFα) and anti-integrin medicines are currently available for regular use in Spain). Which one/s to use depends on disease extension (proctitis, left-sided colitis or extensive disease), disease activity and behavior (early relapse, steroid-dependence, etc.)[7].

The introduction of anti-TNF drugs in the past two decades, has allowed clinicians to change the treatment objectives to the more determined ones mentioned above. Biologics were initially used only for severe steroid-refractory patients, and have been increasingly recommended in different categories, seeking an endoscopic and clinical remission, to avoid steroid overuse, deterioration of patients’ quality of life, colectomy, etc. Anti-TNF drugs are the only ones to have proven effectiveness in obtaining mucosal healing in a high percentage of responding patients. To date, three anti-TNFα drugs are licensed for treatment in moderate-severe UC: infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab.

Golimumab is a fully humanized anti-TNFα monoclonal antibody, administered subcutaneously. As with infliximab and adalimumab, golimumab blocks soluble and trans-membrane TNFα, avoiding permanent TNFα receptor binding. However, compared to the other anti-TNFα, preclinical studies showed that golimumab had greater conformational stability and higher binding affinity for soluble and trans-membrane TNFα. Golimumab reaches peak serum concentrations in 2-6 d, obtaining steady drug levels after 14 wk of treatment[8].

Golimumab was approved for UC by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in the European Union and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States in 2013, and in Spain as the first-line treatment in May 2014. Golimumab has an induction phase with higher dosage in the first two shots; the initial dose is 200 mg subcutaneously at week 0, followed by 100 mg at week 2. Maintenance dose is 50 or 100 mg subcutaneously every 4 wk, depending on the patient’s weight (more or less than 80 kg) in Europe, with a fixed 100 mg dose in the United States.

The golimumab pivotal studies (PURSUIT) demonstrated its efficacy and safety in moderate to severe UC patients, who had an inadequate response to steroids and immunosuppressants, and had not received anti-TNF drugs 12 mo before the study. However, there is hardly any data from daily clinical practice and the best scenario for golimumab use has not yet been defined precisely.

To determine how the new anti-TNF worked on a daily basis with our real-life patients, many of whom were refractory to other treatments (a case that had not been examined in the pre-commercial phase studies), we decided to prospectively record the data of all of the first patients to whom we prescribed golimumab after its approval in Spain. Our objective was also to review the published literature to obtain, and transmit, an idea of the real-life management of UC with golimumab.

We conducted an observational, prospective and multi-center study including patients from 10 of the Hospitals of the Community of Valencia. All UC patients to be treated with the recently approved anti-TNF, golimumab following real-life clinical practice considerations were included from September 2014 to September 2015.

The information was obtained from personal interviews, written and computerized medical histories and each hospital’s IBD database. Demographic data (age, sex, etc.), smoking habits, UC phenotype, previous and current treatments (including anti-TNF, steroid dependence or resistance, loss of response, primary non-responders, etc.), pre-treatment colonoscopy, and Mayo index, were registered. The following hematological parameters were recorded: hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular Hb volume (MCH), red blood cell distribution width (RDW), leukocyte analysis, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), serum ferritin (sferritin), transferrin saturation (TSAT), total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) and serum iron and C-reactive protein (CRP). Routine serum biochemical parameters before starting golimumab treatment and at the end on the study follow-up (14 wk) were also determined. Fecal calprotectin was registered, when available, before and after treatment.

The Montreal classification[9] was used to characterize patients, considering the extent of the disease (E1: ulcerative proctitis; E2: left-sided UC, also known a distal UC; and E3: extensive UC) and its activity/severity (S0: UC in clinical remission; S1: mild UC; S2: moderate UC; and S3: severe UC).

Inclusion criteria were: 18 years of age or older, diagnosis of UC according to the Montreal criteria, signed informed consent and requirement of anti-TNF for the UC, following real-life clinical criteria (moderate to severe UC). Patients were excluded if they were under 18, did not have confirmed UC, did not sign the consent or had a different indication for golimumab.

All patients received 200 mg of golimumab subcutaneously at week 0 and 100 mg at week 2. After the induction treatment, each patient received, in accordance with the data sheet of the EMA[10], 50 mg sc every 4 wk in patients with body weight less than 80 kg, and 100 mg every 4 wk in patients with body weight greater than or equal to 80 kg.

Clinical activity was assessed at week 0 (baseline) and 14 with the physician’s global assessment (PGA) and the partial Mayo score. IBD gastroenterologists carried out the PGA with routine questions, following real-life clinical practice, to gauge disease activity: number of bowel movements, presence or absence of abdominal pain, blood with defecation and objective weight loss. Based on these clinical parameters, PGA was classified as no response, response or clinical remission. Clinical response was defined as complete if there was absence of diarrhea and blood, and partial if there was marked clinical improvement but still persistent rectal bleeding[11]. The definition of clinical response included reduction or removal of steroids. At week 14, clinical response and remission were evaluated, including complete removal of steroids (primary objective) and globally, independently of if the steroids had been removed.

When UC disease activity was measured using the partial Mayo score, clinical remission was defined as a total Mayo score of 2 or lower and every subscore less than 2, and partial response was defined as a decrease from baseline of at least 3 points[12]. Recurrence or aggravation after remission was defined as a partial Mayo score of 5 or higher, an increase from baseline at least 3 points, or additional medication or surgical procedure owing to the development of new symptoms or signs.

In order to identify any adverse events (AEs) associated with the drug, physical examination and laboratory parameters were evaluated during the study, and all AEs were recorded.

Our study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of all participating hospitals. All included patients signed an informed consent authorizing the use of their clinical data for research purposes. Regarding the potential risks of golimumab therapy, prior to enrollment, patients were informed of the known, reported, side effects in patients with UC. Prior to golimumab infusion, written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Additionally, adherence was made to the Principle of Good Clinical Practice and the Helsinki Declaration at all times.

When appropriate, data were presented as the median and interquartile range. Quantitative data were summarized by median and interquartile range (median [interquartile range, IQR]). A Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of continuous variables. Differences between responders and non-responders were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney test. Pearson correlation and Spearman rank were used for correlation analysis. A two-sided P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

The demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Thirty-three consecutive patients with moderately to severely active UC were included in the study. Eighteen (54.5%) were women and the average age was 42 years old (SD 13.75). The mean disease time since diagnosis was 73.5 mo (range 4-360). Concerning the extent of the disease, no patients had ulcerative proctitis (E1), 12 (30%) had left-sided UC (E2) and 21 (70%) patients had extensive UC (E3). Twenty-four were steroid dependent (72.7%) and 7 were classified as steroid refractory (21.3%).

| Variables | |

| Female | 18 (54.4) |

| Mean age | 13 |

| Extent of disease | |

| Proctitis | 0 |

| Left-side colitis | 12 (30) |

| Extensive colitis | 21 (70) |

| Current smokers | 2 (11.1) |

| Endoscopic Mayo score 2-3 | 30 (100) |

| No previous endoscopy | 3 |

| Clinical situation before golimumab | |

| Mild-remission | 5 (15.2) |

| Moderate-severe | 28 (84.8) |

| Golimumab indication | |

| Induction of remission | 28 (84.8) |

| Maintenance of remission | 3 (9.1) |

| Extra-intestinal manifestations | 2 (11.1) |

| Previous anti-TNF use | 24 (72.7) |

| Use of > 1 anti-TNF | 16 (48.5) |

| Previous anti-TNF failure | |

| Primary non-responders | 6 (25) |

| Loss of response | 14 (58.3) |

| Infusion reaction | 4 (16.6) |

| Previous steroid consumption (31 patients had previous steroid consumption) | |

| Steroid-refractory | 7 (27.3) |

| Steroid-dependent | 24 (72.7) |

| Use of steroids at induction | 25 (75.7) |

| Associated immunosuppressors | 12 (36.6) |

| Azathioprine | 11 (33.3) |

| Tacrolimus | 1 (3) |

All patients had moderately to severely active UC (endoscopic Mayo score 2/3) at baseline. With regard to the disease’s clinical activity, at the beginning of treatment with golimumab, 28 (85%) patients had moderate-severe UC (S2-3) and 5 (15.2%) had mild activity.

At study entry, 9 out of 33 patients (27.3%) were anti-TNF treatment naïve, whereas 24/33 patients (72.7%) had previously received infliximab and/or adalimumab. Sixteen patients (66.7%) had previously received two biological agents. The reason for anti-TNF discontinuation for the anti-TNF exposed patients was primary non-response in 6 out of 24 cases (25%), failure or loss of response in 14 (58.3%), and in 4 (16.6%) due to intolerance (delayed hypersensitivity). Twenty-one patients received golimumab monotherapy, whereas 12 (36.6%) patients received combination therapy with thiopurines (11/12) and one patient received tacrolimus. Twenty-five patients received steroids during golimumab induction; of these, 7 (21.2%) maintained steroid use when the study finished.

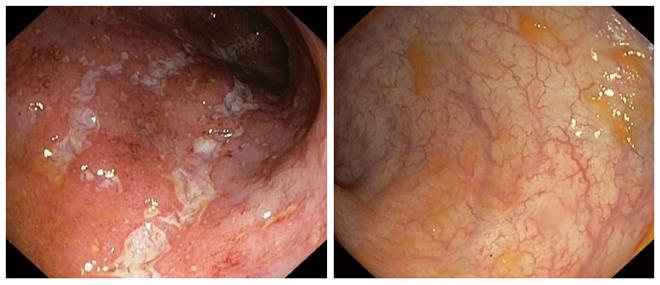

Twenty-three (69.7%) out of 33 UC patients showed clinical response (Figure 1 show the endoscopic images of a patient before and after 12 wk of golimumab) and were steroid-free at week 14 (a decrease from baseline in the partial Mayo score of at least 3 points). Of these, 17 (51.5%) obtained clinical remission (steroid-free) at week 14. When response rates were based on PGA, clinical remission and clinical response rates were 24% (8/33) and 55% (18/33), respectively. Globally, withdrawal of corticosteroids was observed in 70.8% of steroid-dependent patients (17/24) at the end of the study. Finally, 3 out of 10 clinical non-responders needed a colectomy within 3 mo after the first golimumab injection.

When analyzing the nine anti-TNF treatment naïve patients, we observed that six (66.7%) responded but three did not. All responders obtained steroid-free clinical response at week 14.

Mean fecal calprotectin value at baseline was 300 μg/g, (245-1800 percentile 25-75) and 170.5 μg/g at week 14 (49-1031 percentiles 25-75). Mean baseline CRP was 11.9 mg/L and 3.4 mg/L at finish (week 14).

The bivariant analysis did not find any risk factors related to less clinical response, taking into account partial Mayo score, but when partial Mayo score was analyzed, taking into account remission free of steroids, we observed that remission was related to a disease duration of less than 2 years and to not being steroid-dependent. When clinical remission was analyzed based on PGA, bivariant analysis showed that being anti-TNF treatment naïve was a protection factor which was related to better chances of reaching clinical remission (P = 0.01). The other variables did not reach significance in the bivariant analysis (Tables 2 and 3).

| Variable | NO SFR: n = 16 (48.5) | SFR: n = 17 (51.5) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 38.36 ± 13.6 | 46.35 ± 13.7 | NS |

| Mo since diagnosis | 72.20 ± 96.11 | 74.65 ± 67.65 | NS |

| Female sex | 10 (62.5) | 8 (47.1) | NS |

| Diagnosis < 2 yr | 7 (46.7) | 14 (82.4) | 0.03 |

| Anti-TNF naïve | 3 (18.8) | 6 (35.3) | NS |

| > 1 previous anti-TNF | 9 (56.3) | 7 (41.2) | NS |

| Steroid-dependent | 15 (93.8) | 9 (52.9) | 0.01 |

| Steroid-refractory | 4 (25.0) | 3 (17.6) | NS |

| mean ± SD | |||

| Variable | No clinical response n = 8 (24.2) | Clinical response n = 25 (75.8) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 42.71 ± 8.6 | 43.78 ± 14.9 | NS |

| Mo since diagnosis | 56.14 ± 68 | 77.35 ± 87.9 | NS |

| Female sex | 7 (87.5) | 11 (44) | 0.04 |

| Diagnosis < 2 yr | 4 (50) | 17 (70.8) | NS |

| Anti-TNF naïve | 3 (37.5) | 6 (24) | NS |

| > 1 previous anti-TNF | 4 (50.0) | 12 (48.0) | NS |

| Steroid-dependent | 8 (100) | 16 (64.0) | 0.05 |

| Steroid-refractory | 2 (25.0) | 5 (20.0) | NS |

| mean ± SD | |||

Nine of the 33 patients (27.3%) required treatment intensification in the 14 wk of follow-up. Four patients received one shot every 2 wk and five patients had a dosage increase (from 50 to 100 mg, every 4 wk). Three of the nine intensified patients were anti-TNF treatment naïve, and six had not responded to previous anti-TNF. Seven reached remission; only one of the three treatment-naïve and one of the previous non-responders did not reach remission.

Three AEs were observed during the study, which were thought to be related to the golimumab: two patients had urine infection and one had nausea when the drug was administered. The AEs were all considered mild and golimumab was not interrupted.

Golimumab was accepted in Spain as first-line biological treatment for moderate or severe UC only 2 years ago. Scientific evidence of its efficacy was first obtained with the PURSUIT studies (published in 2014). The induction study (PURSUIT-induction)[13] evaluated moderate-to-severe UC anti-TNF treatment naïve patients. This study determined golimumab efficacy until week 6, with clinical response at week 6 as the primary objective. Fifty-one percent of the patients that received 200/100 mg golimumab and 30.3% of those treated with placebo had clinical response at week 6 (P < 0.001). In the golimumab group 17.8% obtained clinical remission, whereas only 6.4% of the placebo patients did (P < 0.001).

The second PURSUIT study (PURSUIT-maintenance)[14] evaluated 456 patients that had responded in the previous golimumab induction study. The primary objective was maintenance of clinical response through week 54. There was clinical response in 47% of the patients who received 50 mg of golimumab every 4 wk, 49.7% of those who had 100 mg/every 4 wk and 31.2% of those given placebo, with significant differences between the golimumab patients and the placebo group (50 mg golimumab vs placebo: P < 0.01, and 100 mg vs placebo: P < 0.001). No differences were found in the amount of severe adverse events in the three groups.

When we conducted the study, no studies had been published regarding real-life results with golimumab. Currently, many studies are on-going, some of which have presented their preliminary results at IBD Congresses, and two have been recently published[15,16]. Detrez et al[15] included 21 patients and determined golimumab levels and antibodies in the first 14 wk of treatment, to correlate these with clinical response and remission.

The most relevant result of Castro-Laria et al[16] study (which included 23 patients) was that 74% of their patients were able to withdraw steroids, which is quite similar to our results. In our study 70.8% of the steroid-dependent patients and 69.7% of all the patients were steroid-free at the end of follow-up. Although both studies, Castro-Laria’s and ours, do not include many patients due the fact that it is a recently approved drug, and not forgetting that the Castro-Laria et al[16] 23-patient study was retrospective, a significant real-life steroid withdrawal in 70.8% and 74% of the cases is clinically relevant. In the PURSUIT-maintenance study, corticosteroid-free remission at 54 wk among those who received corticosteroids at baseline was statistically non-significant among the groups (PURSUIT2).

An unpublished real-life experience, retrospective Spanish study, which included 142 patients, recently presented its results at a congress. They observed that, after a median follow-up of 10 mo, 67 patients (47%) maintained clinical response, and, of these, 49 (35%) were in corticosteroid-free remission[17], with a long-term partial loss of response, which is similar to other anti-TNF[18,19]. Therefore, the current limited published data (Castro-Laria’s retrospective and our prospective study) point to a very good initial response to golimumab, which enables steroid withdrawal; preliminary unpublished data show a decrease in the steroid-free percentage of patients over time.

The patients included in our study had a mean age of 42, with extensive moderate-severe colitis (70%) and were steroid-dependent. Seventy-three percent of the patients had previously received anti-TNF drugs (67% of these had previously been on both infliximab and adalimumab when they were included), which is logical because this is real-life practice and patients had received the anti-TNFs that were available until then. The most frequent reason to change to golimumab was loss of response (58%) to the previous anti-TNF, although a not inconsiderable 25% (6 of the 24 who had previously received anti-TNF) were directly primary non-responders to previous anti-TNF drugs. This would lead us to predict an insufficient response with the new anti-TNF (golimumab) in some patients and a delayed loss of response in others. However, 69.7% of the patients had clinical response (a decrease from baseline in the partial Mayo score of at least 3 points) and were able to cease steroids, and 51.5% of these reached clinical remission at week 14. These percentages were lower when taking into account the PGA (55% of clinical response and 24% of clinical remission). Steroid-sparing in previously corticosteroid-dependent patients was especially striking (70.8%), when follow-up ended. These patients will be followed to determine if they lose response, as with other anti-TNF, but at least golimumab was able to win back an important number of our patients, including many of the primary non-responders.

Although dosage intensification worked for some patients (7 of the 9 that received higher or more frequent dosages), 3 of the 10 which did not respond ended up in colectomy 3 mo after the first golimumab injection. According to Detrez et al[15] the response to golimumab treatment is related to serum golimumab concentrations and shows a large variation between patients. Serum golimumab levels could be of use at induction (week 6), in patients with insufficient response who might need higher doses of golimumab, in order to avoid changes to other medical or surgical treatments.

As would be expected, anti-TNF treatment naïve patients had more possibilities than non-naïve patients of achieving clinical remission, as well as patients with short-duration disease, and not being steroid dependent. This was not observed in the Castro-Laria et al[16] study, probably because of the small sample size, nor in a Canadian study presented as abstract[20]. Bressler et al[20] presented in the form of an abstract the preliminary results of a nationwide study in Canada that included 136 UC patients treated with golimumab, 72.1% of which were anti-TNF treatment naïve, which might explain why they did not find differences. In accordance with our results, Taxonera et al[17] had a sample that included 80% of anti-TNF experienced patients; they observed significantly lower clinical response and remission rates in anti-TNF experienced patients when compared to naïve.

The reduction of fecal calprotectin with golimumab treatment that we observed is encouraging but the finding should be taken with caution because of the few centers that had the determination available. It should be contrasted with future studies which include a larger number of patients and samples to see what factors are related with calprotectin normalization, which is known to go hand in hand with mucosal healing. This is also the case for the CRP; that the reduction did not reach significance may be because of the small sample size in each CRP group.

The endoscopic images of a patient who responded to treatment are shown below (Figure 1). Improvement was outstanding; the mucosa went from a Mayo score of 3 to 0 (normal macroscopic mucosa). Since the study was based on daily practice, many patients did not have a control endoscopy, and many of the ones that did have it, did not have pictures taken. Although changes were sometimes quite remarkable, they were not taken into account when analyzing the results because endoscopic improvement was not part of the objectives and, therefore, the data was not prospectively included in all cases.

Adverse drug events were limited and mild in our cohort of patients. Golimumab seemed quite safe and was only related to the appearance of two urine infections and one case of nausea. This is in line with what has been reported by others in abstract form[21].

This study, to our knowledge, is one of the first real-life experience prospective studies with golimumab to be published. Although the results have to be taken with caution because, to-date, there are only two prospective and one retrospective studies published (Detrez et al[15]’s, Castro-Laria et al[16]’s and ours) and they all include small sample sizes (23, 21 and 33, respectively), the studies do offer promising results because they confirm the efficacy of this new anti-TNF in real-life practice. In our study, golimumab allows steroid-sparing in a high number of steroid-dependent patients. It is associated to good clinical response in the first 14 wk. It may even be more effective in anti-TNF treatment naïve patients, although it is also a compelling treatment for experienced anti-TNF patients. More studies should be performed and will hopefully be published soon to confirm these conclusions.

Pivotal studies have demonstrated golimumab’s benefits in moderate or severe ulcerative colitis (UC), but since golimumab was accepted for clinical practice quite recently, real-life studies are still scarce.

This article presents the results of one of the first real-life short-term studies. This observational, prospective and multi-center study in moderate-severe UC patients, confirmed golimumab’s short-term (14 wk) effectiveness.

A high percentage of patients had responded and were off steroids at the end of follow-up. No severe adverse events were observed. Intensification (reducing the drug administration interval or increasing the dosage) may be useful in many slow-to-respond cases.

The data support the use of golimumab in real-life practice. Future studies are necessary to confirm the drug’s long-term benefit.

The authors present interesting data about the role of golimumab in short-term effectiveness therapy of UC. The authors report that a real-life practice study endorses golimumab’s promising results, demonstrating its short-term effectiveness and confirming it as a safe drug, during the induction phase. The manuscript is well written, has important clinical message, and should be of great interest to the readers.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Stewart Day AS, Wu B, Lakatos PL S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1713-1725. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 812] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 861] [Article Influence: 66.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ordás I, Eckmann L, Talamini M, Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2012;380:1606-1619. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1151] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1295] [Article Influence: 107.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | da Silva BC, Lyra AC, Rocha R, Santana GO. Epidemiology, demographic characteristics and prognostic predictors of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9458-9467. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 167] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 162] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2004;53 Suppl 5:V1-16. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Bartnik W. Choroby jelita grubego. In: Gajewski P, editor. Interna Szczeklika - Podręcznik chorób wewnętrznych. Medycyna Praktyczna, Kraków 2015; 997-1010. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Moćko P, Kawalec P, Pilc A. Safety Profile of Biologic Drugs in the Therapy of Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:870-879. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, Windsor A, Colombel JF, Allez M, D’Haens G, D’Hoore A, Mantzaris G, Novacek G. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:991-1030. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 728] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 683] [Article Influence: 56.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pugliese D, Felice C, Landi R, Papa A, Guidi L, Armuzzi A. Benefit-risk assessment of golimumab in the treatment of refractory ulcerative colitis. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2016;8:1-7. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a working party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19:5A-36A. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Simponi Summary of Product Characteristics [online]. Accessed January 27, 2015. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR__Product_ Information/human/000992/WC500052368.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Ferrante M, Vermeire S, Katsanos KH, Noman M, Van Assche G, Schnitzler F, Arijs I, De Hertogh G, Hoffman I, Geboes JK. Predictors of early response to infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:123-128. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 98] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462-2476. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2744] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2694] [Article Influence: 141.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, Zhang H, Strauss R, Johanns J, Adedokun OJ, Guzzo C, Colombel JF, Reinisch W. Subcutaneous golimumab induces clinical response and remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:85-95; quiz e14-15. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 563] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 605] [Article Influence: 60.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, Zhang H, Strauss R, Johanns J, Adedokun OJ, Guzzo C, Colombel JF, Reinisch W. Subcutaneous golimumab maintains clinical response in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:96-109.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 474] [Article Influence: 47.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Detrez I, Dreesen E, Van Stappen T, de Vries A, Brouwers E, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Ferrante M, Gils A. Variability in Golimumab Exposure: A ‘Real-Life’ Observational Study in Active Ulcerative Colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:575-581. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Castro-Laria L, Argüelles-Arias F, García-Sánchez V, Benítez JM, Fernández-Pérez R, Trapero-Fernández AM, Gallardo-Sánchez F, Pallarés-Manrique H, Gómez-García M, Cabello-Tapia MJ. Initial experience with golimumab in clinical practice for ulcerative colitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016;108:129-132. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Taxonera C, Bertoletti F, Rodriguez C, Marin I, Arribas J, Martinez-Montiel P, Sierra M, Arias L, Rivero M, Juan A. P404 Real-life experience with golimumab in ulcerative colitis patients according to prior anti-TNF use. 11th Congress of ECCO- IBD; 2016 Mar 16-19. 2016;. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Murthy SK, Greenberg GR, Croitoru K, Nguyen GC, Silverberg MS, Steinhart AH. Extent of Early Clinical Response to Infliximab Predicts Long-term Treatment Success in Active Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2090-2096. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Baki E, Zwickel P, Zawierucha A, Ehehalt R, Gotthardt D, Stremmel W, Gauss A. Real-life outcome of anti-tumor necrosis factor α in the ambulatory treatment of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3282-3290. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bressler B, Williamson MA, Camacho F, Sattin BD, Satinhart AH. Mo1902 Real World Use and Effectiveness of Golimumab for Ulcerative Colitis in Canada. Gastroenterology. 2016;4 Suppl 1:S811. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Varvara D, Costantino G, Privitera AC, Principi B, Cappello M, Mazzuoli S, Paiano P, Tursi A, Paese P, Fries W. P363 Efficacy and safety of golimumab in patients with ulcerative colitis: a prospective multicentre study. 11th Congress of ECCO- IBD; 2016 Mar 16-19. 2016;. [Cited in This Article: ] |