Published online Oct 7, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i37.8414

Peer-review started: March 23, 2016

First decision: May 12, 2016

Revised: July 4, 2016

Accepted: July 31, 2016

Article in press: August 1, 2016

Published online: October 7, 2016

To define good and poor regression using pathology and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) regression scales after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for rectal cancer.

A systematic review was performed on all studies up to December 2015, without language restriction, that were identified from MEDLINE, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (1960-2015), and EMBASE (1991-2015). Searches were performed of article bibliographies and conference abstracts. MeSH and text words used included “tumour regression”, “mrTRG”, “poor response” and “colorectal cancers”. Clinical studies using either MRI or histopathological tumour regression grade (TRG) scales to define good and poor responders were included in relation to outcomes [local recurrence (LR), distant recurrence (DR), disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS)]. There was no age restriction or stage of cancer restriction for patient inclusion. Data were extracted by two authors working independently and using pre-defined outcome measures.

Quantitative data (prevalence) were extracted and analysed according to meta-analytical techniques using comprehensive meta-analysis. Qualitative data (LR, DR, DFS and OS) were presented as ranges. The overall proportion of poor responders after neo-adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy (CRT) was 37.7% (95%CI: 30.1-45.8). There were 19 different reported histopathological scales and one MRI regression scale (mrTRG). Clinical studies used nine and six histopathological scales for poor and good responders, respectively. All studies using MRI to define good and poor response used one scale. The most common histopathological definition for good response was the Mandard grades 1 and 2 or Dworak grades 3 and 4; Mandard 3, 4 and 5 and Dworak 0, 1 and 2 were used for poor response. For histopathological grades, the 5-year outcomes for poor responders were LR 3.4%-4.3%, DR 14.3%-20.3%, DFS 61.7%-68.1% and OS 60.7-69.1. Good pathological response 5-year outcomes were LR 0%-1.8%, DR 0%-11.6%, DFS 78.4%-86.7%, and OS 77.4%-88.2%. A poor response on MRI (mrTRG 4,5) resulted in 5-year LR 4%-29%, DR 9%, DFS 31%-59% and OS 27%-68%. The 5-year outcomes with a good response on MRI (mrTRG 1,2 and 3) were LR 1%-14%, DR 3%, DFS 64%-83% and OS 72%-90%.

For histopathology regression assessment, Mandard 1, 2/Dworak 3, 4 should be used for good response and Mandard 3, 4, 5/Dworak 0, 1, 2 for poor response. MRI indicates good and poor response by mrTRG1-3 and mrTRG4-5, respectively.

Core tip: The degree of primary tumour regression following neo-adjuvant therapy identified on final histopathological specimens is a prognostic factor and response variation has allowed risk stratification, aiding in post-surgical treatment and follow-up decisions. To do this effectively, we need to have a common language for defining good and poor response. Definitions of response using histopathology scales are heterogenous with 19 different scales. There is one pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scale. Outcomes of recurrence and survival histopathology regression assessments should use Mandard 1, 2/Dworak 3, 4 for good response and Mandard 3, 4, 5/Dworak 0, 1, 2 for poor response. MRI indicates good and poor response by mrTRG1-3 and mrTRG4-5, respectively.

- Citation: Siddiqui MRS, Bhoday J, Battersby NJ, Chand M, West NP, Abulafi AM, Tekkis PP, Brown G. Defining response to radiotherapy in rectal cancer using magnetic resonance imaging and histopathological scales. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(37): 8414-8434

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i37/8414.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i37.8414

The multidisciplinary treatment of rectal cancer has markedly improved and led to better patient outcomes over the last three decades[1]. The reasons for this are multifactorial, but one important factor is the use of neo-adjuvant or adjuvant therapies[2].

The degree of primary tumour regression following neo-adjuvant therapy, identified on final histopathological specimens, has been shown to be a prognostic factor[3,4]. The variation in response allows clinicians to risk-stratify patients after surgery, which may help in post-operative decisions, such as who to treat with adjuvant chemotherapy and the intensity of follow-up.

Clinical studies use a number of different tumour regression grade (pTRG) scales to classify the degree of tumour response to neo-adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy (CRT). This often results in confusion as to whether a good or poor response has been achieved, with subsequent uncertainty regarding treatment and prognostic implications. This problem was highlighted by MacGregor et al[1] who stressed the importance of a universally accepted standard.

There has been no review of the reported pTRG scales to date. It is necessary to highlight the heterogeneity in these scales, in order to consolidate the current definitions with the purpose of converging towards a set of consensus definitions.

A newer method of assessing tumour regression relies on MRI (mrTRG), which has been validated as a prognostic tool. This may supercede pTRG, as it has the advantage of assessing tumour response before surgery. As such, it has the potential for enabling response-orientated tailored treatment, including alteration of the surgical planes, additional use of chemotherapy, or deferral of surgery[5-7].

This article investigates all the pathology tumour regression scales used to define good and poor response after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for rectal cancer, to establish the true prevalence of poor responders and to identify the best scales to use in relation to outcomes.

The title, methods and outcome measures were stipulated in advance and the protocol is available in the PROSPERO database[8].

All clinical, histopathological and imaging studies that define or attempt to define good and poor responders after neo-adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancers were identified. Included studies were those investigating rectal cancer response to neo-adjuvant therapy incorporating chemotherapy, radiotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy with different protocols. All clinical studies were chosen that defined good and poor response in relation to TRG or degree of response according to histopathology using terms such as “poor response”, “minor response”, “less response”, “good response”, “major response” or “more response”.

All rectal cancer patients treated with long course radiotherapy or an interval period to surgery were selected for this review. All sensitizing chemotherapy protocols were included. Any surgical resection was included. Studies were also included with any post-operative adjuvant practice.

Excluded studies were those that did not specifically state whether a response was good or poor, or that qualify it with some form of inference in the paper. Further exclusions were for: non-conventional deliveries of neo-adjuvant therapy, such as endo-rectal brachytherapy; trans-anal endoscopic microsurgery (commonly known as TEMS) and local excisions; and, when the reporting scale was in obvious contradiction with the order given in the original studies[9].

The original papers reporting the various pTRG scales were identified and articles that used the scales in clinical, pathological and MRI studies were used in the current study.

The primary hypothesis was that there is an optimal histopathological TRG scale that appropriately distinguishes between good and poor response. The secondary hypothesis was that the mrTRG scale differentiates between good and poor response. This was investigated by first reviewing the clinical studies examining the response of rectal cancer to neo-adjuvant therapy. These studies were used to show the range of definitions of good and poor response according to histopathology and MRI. This was then utilised to identify the optimal scale for identifying good and poor response after neo-adjuvant therapy for rectal cancer based on recurrence and survival outcomes.

The Cochrane library, CENTRAL, EMBASE, CINAHL and PubMed databases were searched between January 1935 and December 2015. Relevant articles referenced in these publications were obtained and the “related article” function was used to widen the results. This was complemented by hand searches and cross-references from papers identified during the initial search. No language restriction was applied.

The text words “preoperative”, “neo-adjuvant”, “tumour regression”, “poor responder”, “good responder”, “regression grading”, “regression grade” and “rectal cancer” were used in combination with the medical subject headings “adjuvant combined modality therapy” and “rectal cancer”. Irrelevant articles not fulfilling the inclusion criteria were excluded.

Each included article according to our review criteria was reviewed by two researchers (MRSS and JB). Where more specific data or missing data was required, the authors of the manuscripts were contacted. Data was entered onto an Excel worksheet and compared between authors. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion, and if no consensus could be reached a third author (GB) would decide.

Data were extracted that related to the definition of good and poor response according to the TRG scales reported in clinical, histopathological and imaging studies. The ranges of permutations of each TRG scale to define good or poor response were also documented and the most commonly used definitions identified. The primary hypothesis was proven by examining all of the studies on response to neo-adjuvant therapy and there is a single definition (which may include other scales) that consistently differentiates between good and poor responses as defined by local recurrence (LR), distant recurrence (DR), disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS).

Quality assessment and risk of bias was not formally assessed due to the exploratory nature of this review. Validity of other studies was benchmarked to studies that identified a significant difference. Clinical heterogeneity can be seen in the table of characteristics presented as Table 1.

| Ref. | Year | Chemotherapy protocol with radiotherapy | Radiotherapy protocol (Gy) | Surgical procedures | TME | Time to surgery (wk) | Cancer stage pre neo-adjuvant therapy | Adjuvant therapy |

| Gambacorta et al[21] | 2004 | Ralitrexed | 50.4 | APR/AR/Col-Anal resection/Stoma | Y | 6-8 | Stage 2 or 3 | Y |

| Pucciarelli et al[28] | 2004 | Fluorouracil, leucovorin carboplatin, oxaliplatin | 45-50.4 | APR/AR/Hartmann’s | Y | 2-8 | T2/3/4, N0/1/2 | Y |

| Beddy et al[17] | 2008 | Fluorouracil | 45-50 | APR/AR | Y | T3/4, N1/2 | ||

| Giralt et al[22] | 2008 | Tegafir uracil, leucovorin | 45 + 9 boost | APR/AR | Y | 4-6 | T3/4, N0/1/2 | Y |

| Horisberger et al[24] | 2008 | Capecitabine, irinotecan | 50.4 | APR/AR/stoma | Y | 4-7 | T2/3/4, N+ | |

| Suárez et al[31] | 2008 | Fluoropyridine-based | 50.4 | APR/AR/Hartmann’s | Y | 6 | Stage 2 or 3 | Y |

| Bujko et al[18] | 2010 | Fluorouracil, leucovorin | 50.4 | APR/AR/Hartmann’s | Y | 4-6 | Stage 2 or 3 | Y |

| Avallone et al[13] | 2011 | Fluorouracil, levo-folinic acid, ralitrexed, oxaliplatin | 45.0 | APR/AR/Stoma | Y | < 8 | T3/4, N0/1/2 | Y |

| Eich et al[19] | 2011 | Fluorouracil | 50.4 | APR/AR/TEMS/Intersphincteric Surgery | Y | 4-6 | Stage 1,2 or 3 | Y |

| Min et al[27] | 2011 | Fluorouracil, leucovorin | 50.4 | APR/AR | Y | 6 | T3/4, N0/1/2 | |

| Shin et al[30] | 2011 | Fluorouracil | 25-50.4 | APR/AR/Pan | 4-6 | T3/4 | ||

| Huebner et al[25] | 2012 | Fluorouracil | APR/AR | T1/2/3/4, N0/1/2 | Y | |||

| Lim et al[26] | 2012 | Capecitabine, fluorouracil, leucovorin | 44-46+4.6 boost | Radical Proctectomy | Y | T3/4, N+ | Y | |

| Roy et al[29] | 2012 | Capecitabine, fluorouracil | 45-50 | Y | 4-6 | T1/2/3/4, N0/1/2 | Y | |

| Vallböhmer et al[32] | 2012 | Fluorouracil | 50.4 | APR/AR | Y | T3/4, N0/1/2 | ||

| Winkler et al[33] | 2012 | Capecitabine, oxaliplatin | 45-50.4 | Y | 4-6 | Stage 2 or 3 | Y | |

| Elezkurtaj et al[20] | 2013 | Fluorouracil | 50.4 | Y | 4-6 | |||

| Hermanek et al[23] | 2013 | APR/AR/Hartmann’s | Y | Y | ||||

| Fokas et al[14] | 2014 | Fluorouracil | 50.4 | APR/AR | Y | 4-6 | T3/4 or any T and N+ | Y |

| Santos et al[16] | 2014 | Fluorouracil | 50.4 | APR/AR | Y | < 8 | T2N+ or T3/4 | Y |

| Hav et al[15] | 2015 | Fluorouracil, cetuximab, oxaliplatin | 25-45 | AR/Hartmann’s | Y | 6-8 | T3/4 or any T and N+ |

As part of assessing overall prevalence of poor responders, cumulative meta-analytical techniques were used. Analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 2006 (Version 2, Biostat, Englewood, NJ, United States) for Windows 10[10]. In a sensitivity analysis, 0.5 was added to each cell frequency for trials in which no event occurred, according to the method recommended by Deeks et al[11] and was not considered to affect the overall result necessitating the Peto method[12]. Where only a single patient was present in any of the groups, this was excluded due to the excessive effect of zero cell correction. Outcomes were reported as event rates. Forest plots were used for the graphical display.

For the outcome of prevalence, publication bias was assessed using funnel plots. We used the plots to subjectively assess asymmetry and conducted an Egger test for quantitative assessment.

Study selection and characteristics

There were 328 references. Full texts of 85 papers were reviewed. Overall, 21 articles were of relevance and reported 25 definitions for poor response in accordance with the TRG[13-33]. Of these, 16 articles also defined good response. Table 1 shows the characteristics of individual studies.

Histopathological methods of classifying regression: There were 19 TRG scales reported across the studies[18,25,34-51] (Table 2). Only one TRG system incorporated whether a response was poor or good[36] and used a categorical TRG scale based on the one described by Dworak et al[35].

| TRG scale | Mandard |

| (Low no. - More regression)[43] | |

| 0 | |

| 1 | Complete regression - absence of residual cancer and fibrosis |

| 2 | Presence of rare residual cancer |

| 3 | An increase in the number of residual cancer cells, but predominantly fibrosis |

| 4 | Residual cancer outgrowing fibrosis |

| 5 | Absence of regressive changes |

| TRG scale | Modified Mandard (Ryan) |

| (Low no. - More regression)[37] | |

| 0 | |

| 1 | TRG 1 and 2 of the Mandard scale |

| 2 | TRG 3 of the Mandard scale |

| 3 | TRG 4 and 5 of the Mandard scale |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| TRG scale | Werner and Hoffler |

| (Low no. - More regression)[41] | |

| 0 | |

| 1 | 0% viable tumour cells |

| 2 | < 10% viable tumour cells |

| 3 | 10%-50% viable tumour cells |

| 4 | > 50% viable tumour cells |

| 5 | No regression |

| TRG scale | Dworak |

| (Low no. - Less regression)[35] | |

| 0 | No regression |

| 1 | Dominant tumour mass with obvious fibrosis and/or vasculopathy |

| 2 | Dominant fibrotic change with few |

| tumour cells or groups(easy to find) | |

| 3 | Very few tumour cells in fibrotic tissue with or without mucous substance |

| 4 | No tumour cells, only fibrotic mass (total regression or response) |

| 5 | |

| TRG scale | Modified Dworak |

| (Low no. - Less regression)[38] | |

| 0 | No regression |

| 1 | Regression ≤ 25% of tumour mass (dominant tumour mass with obvious fibrosis and/or vasculopathy) |

| 2 | Regression > 25%-50% of tumour mass (dominantly fibrotic changes with few tumour cells of groups, easy to find) |

| 3 | Regression > 50% of tumour mass (very few tumour cells in fibrotic tissue with or without mucous substance) |

| 4 | Complete (total) regression (or response): no vital tumour cells |

| 5 | |

| TRG scale | AJCC 7th Edition[48] |

| 0 | Complete-no viable cells present |

| 1 | Moderate-single cells/small groups of cancer cells |

| 2 | Minimal-residual cancer outgrown by fibrosis |

| 3 | Poor-minimal or no tumour kill, extensive residual cancer |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| TRG scale | Memorial Sloan-Kettering (Low no. - Less regression)[47] |

| 0 | 0%-85% regression |

| 1 | 86-99% regression |

| 2 | 100% regression |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| TRG scale | Cologne |

| (Low no. - Less regression)[40] | |

| 0 | |

| 1 | > 50 % Viable rectal tumour cells |

| 2 | 10%-50% Viable rectal tumour cells |

| 3 | Near complete regression with < 10% Viable rectal tumour cells |

| 4 | Complete regression (pathologic complete remission and ypT0) |

| TRG scale | Bujko/Glynne Jones |

| (Low no. - More regression)[18,44] | |

| 0 | No cancer cells |

| 1 | A few cancer foci in less than 10% of tumour mass |

| 2 | Cancer seen in 10%-50% of tumour mass |

| 3 | Cancer cells seen in more than 50% of tumour mass |

| 4 | |

| TRG scale | College of American Pathologists[50] |

| 0 | Complete response: No residual tumour |

| 1 | Marked response: Minimal residual cancer |

| 2 | Moderate response: Residual cancer outgrown by fibrosis |

| 3 | Poor or no response: Minimal or no tumour kill; extensive residual cancer |

| 4 | |

| TRG scale | RCPath system |

| (Low no. - More regression)[42] | |

| 0 | |

| 1 | No residual cells and/or mucus lakes only |

| 2 | Minimal residual tumour i.e., microscopic residual tumour foci only |

| 3 | No marked regression |

| 4 | |

| TRG scale | RCRG system |

| (Low no. - More regression)[34] | |

| 0 | |

| 1 | Sterilisation or only microscopic foci of adenocarcinoma with marked fibrosis |

| 2 | Marked fibrosis but macroscopic disease present |

| 3 | Little or no fibrosis with abundant macroscopic disease |

| 4 | |

| TRG scale | Mod RCRG system |

| (Low no. - More regression)[45] | |

| 0 | |

| 1 | Macroscopic features may be varied. Microscopy reveals no tumour or < 5% of area of abnormality |

| 2 | Macroscopic features may be varied. Microscopy reveals combination of viable tumour and fibrosis. Tumour comprises 5%-50% of overall area of abnormality |

| 3 | Macroscopic or microscopic features may not be significantly different. Over 50% comprises tumour. Some fibrosis may be present but no more than untreated cases |

| 4 | |

| TRG scale | Japanese |

| (Low no. - Less regression)[25] | |

| 0 | No regression |

| 1a | Minimal effect (necrosis less than 1/3) |

| 1b | Mild effect (necrosis less than 2/3 but more than 1/3) |

| 2 | Moderate effect (necrosis more than 2/3 of the lesion) |

| 3 | No tumour cells |

| TRG scale | Ruo |

| (Low no. - Less regression)[39] | |

| 0 | No evidence of response |

| 1 | 1% to 33% response |

| 2 | 34% to 66% response |

| 3a | 67% to 95% response |

| 3b | 96% to 99% response |

| 4 | 100% response (no viable tumour identified) |

| TRG scale | Junker and Muller |

| (Low no. - Less regression)[46] | |

| 1 | No regression |

| 2a | > 10% residual tumour cells |

| 2b | < 10% residual tumour cells |

| 3 | Total regression (no viable tumour cells) |

| TRG scale | Rodel |

| (Low no. - Less regression)[36] | |

| Poor | TRG 1 and 0 of the Dworak scale |

| Intermediate | TRG 2 and 3 of the Dworak scale |

| Complete | TRG 4 of the Dworak scale |

| TRG scale | Four point scale |

| Swellengrebel et al[49] | |

| pCR | Pathological complete response without residual primary tumour |

| Near pCR | Isolated residual tumour cells/small groups of residual tumour cells |

| Response | Stromal fibrosis outgrowing tumour |

| No response | No regression or those with stromal fibrosis outgrown by tumour |

| TRG scale | Modified Mandard TRGN by Dhadda et al[51] |

| TRGN 1 | Complete regression with absence of residual cancer and fibrosis extending through the wall |

| TRGN 2 | Presence of rare residual cancer cells scattered through the fibrosis |

| TRGN 3 | An increased number of residual cancer cells, but fibrosis is still predominant |

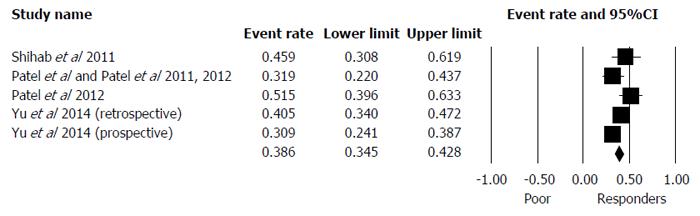

From the search, nine scales[18,25,34-36,38,40,43,44,46] were used in 25 reports (21 articles) to define poor response[13-33]. From these 25 reports, the nine scales were used in different combinations to produce 16 individual definitions of poor response (Table 3). The overall proportion of poor responders after neo-adjuvant CRT was 37.7% (95%CI: 30.1-45.8) (Table 4, Figure 1). Study characteristics can be seen in Table 1. Table 5 shows the scales that define poor response with their permutations. Most studies used the Mandard or Dworak TRG scales. The studies using the Mandard scale[13,16,21,22,28-31] defined poor response as Mandard TRG 3 to 5, 4 or 4 to 5. The Dworak scale uses a similar numerical scale in the opposite direction to the Mandard system. From the articles that use the Dworak classification for their definitions[14-16,20,25,26,29,33], a poor response was defined as Dworak 0 to 1, 1, 1 to 2 or 0 to 2.

| Poor response | Good response | ||

| TRG grading system | Studies that used the scale | TRG grading system | Studies that used the scale |

| Mandard TRG 3,4,5 | Suárez et al[31] | Mandard TRG 1,2 | Suárez et al[31] |

| Santos et al[16] | Gambacorta et al[21] | ||

| Santos et al[16] | |||

| Mandard TRG 4 | Gambacorta et al[21] | Mandard TRG 2,3 | Avallone et al[13] |

| Giralt et al[22] | |||

| Mandard TRG 4,5 | Avallone et al[13] | Mandard TRG 1,2,3 | Roy et al[29] |

| Roy et al[29] | Pucciarelli et al[28] | ||

| Pucciarelli et al[28] | Shin et al[30] | ||

| Shin et al[30] | |||

| Dworak 1 | Winkler et al[33] | Dworak TRG 2,3,4 | Huebner et al[25] |

| Roy et al[29] | |||

| Dworak TRG 0,1 | Huebner et al[25] | Dworak TRG 2,3 | Fokas et al[14] |

| Roy et al[29] | |||

| Fokas et al[14] | |||

| Dworak TRG 1,2 | Lim et al[26] | Dworak TRG 3,4 | Lim et al[26] |

| Elezkurtaj et al[20] | |||

| Santos et al[16] | |||

| Hav et al[15] | |||

| Dworak TRG 0,1,2 | Elezkurtaj et al[20] | Dworak TRG 3 | Winkler et al[33] |

| Hav et al[15] | |||

| Santos et al[16] | |||

| Rodel TRG 3 [Dworak 0,1] | Min et al[27] | Japanese TRG 2,3 | Horisberger et al[24] |

| Rodel TRG 3 [Wittekind (mod Dworak 0,1)] | Hermanek et al[23] | Japanese TRG 3 | Vallböhmer et al[32] |

| Japanese TRG 0,1a,1b | Horisberger et al[24] | Miller Junker TRG 2a and 2b | Vallböhmer et al[32] |

| Japanese TRG 1 | Vallböhmer et al[32] | Cologne TRG 3 and 4 | Vallböhmer et al[32] |

| Miller Junker TRG 1 | Vallböhmer et al[32] | Glynne Jones TRG 1 | Bujko et al[18] |

| Miller Junker TRG 1,2a | Eich et al[19] | ||

| Cologne TRG 1,2 | Vallböhmer et al[32] | ||

| Glynne Jones TRG 3 | Bujko et al[18] | ||

| Wheeler RCRG TRG 2 | Beddy et al[17] | ||

| TRG grading system | No. of reports (total 25 reports from 21 studies) | Proportion of poor responders | Lower limit of confidence Interval | Upper limit of confidence Interval |

| Mandard | 8 | 34.9 | 22.8 | 49.4 |

| Dworak | 8 | 47.4 | 32.5 | 62.7 |

| Junker/Muller | 2 | 50.8 | 28.8 | 72.5 |

| Japanese | 2 | 35.0 | 20.4 | 52.9 |

| Wheeler | 1 | 38.9 | 30.8 | 47.7 |

| Bujko/Glynne-Jones | 1 | 22.1 | 15.8 | 30.0 |

| Rodel based on Dworak | 1 | 52.2 | 44.9 | 59.5 |

| Rodel based on Wittekind (modified Dworak) | 1 | 14.7 | 10.6 | 19.9 |

| Cologne | 1 | 7.1 | 3.2 | 14.8 |

| Ref. | Year | TRG scale used (original disease application) | Are the scales reported accurately? | Poor response definition | Total (n) | Poor responders (n) | Average F/up in months | LR (%) 5 yr | DR (%) 5 yr | DFS (%) | OS (%) |

| Gambacorta et al[21] | 2004 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 4 | 54 | 10 | 25 | ||||

| Pucciarelli et al[28] | 2004 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 4 and 5 | 106 | 52 | 42 | ||||

| Beddy et al[17] | 2008 | Wheeler (rectal) | Yes | TRG 2 | 126 | 49 | 37 | 21 | Yr. 5: 71 | ||

| Giralt et al[22] | 2008 | Mandard (oesophagus) | No | TRG 4 | 68 | 7 | |||||

| Horisberger et al[24] | 2008 | Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (rectal) | Yes | TRG 0 and 1a and 1b | 59 | 26 | |||||

| Suárez et al[31] | 2008 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 3 and 4 and 5 | 119 | 83 | 33 | 3.41 | 14.31 | Yr. 2: 83.6 | |

| Yr. 3: 73.8 | |||||||||||

| Bujko et al[18] | 2010 | Glynne Jones/Bujko (rectal) | Yes | TRG 3 | 131 | 29 | 48 | 26 | 47 | Yr. 4: 47 | |

| Avallone et al[13] | 2011 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 4 and 5 | 63 | 9 | 60 | Yr. 5: Prob free of recurrence 562 | |||

| Eich et al[19] | 2011 | Müller and Junker (lung) | Yes | TRG 1 and 2a | 72 | 28 | 28 | Yr. 2: 76 ± 14.8 | |||

| Min et al[27] | 2011 | Rodel (rectal based on Dworak) | Yes | Categorised as poor according to Rodel and based on TRG 0 and 1 on Dworak scale | 178 | 93 | 43 | 21 | 31 | ||

| Shin et al[30] | 2011 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 4 and 5 | 102 | 50 | 40.3 | Yr. 3: 72.6 | |||

| Huebner et al[25] | 2012 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 0+1 | 237 | 61 | |||||

| Lim et al[26] | 2012 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 1+2 | 581 | 357 | 61 | 9.5 | 27.2 | Yr. 5: 63.6 | Yr. 5: 71.3 |

| Roy et al[29] | 2012 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 0 and 1 | 75 | 42 | Yr. 2: 68.9 | Yr. 2: 92.6 | |||

| Roy et al[29] | 2012 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 4 and 5 | 75 | 24 | Yr. 2: 60.3 | Yr. 2: 87.3 | |||

| Vallböhmer et al[32] | 2012 | Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (rectal) | Yes | TRG 1 | 85 | 23 | |||||

| Vallböhmer et al[32] | 2012 | Junker Miller (lung) | Yes | TRG 1 | 85 | 6 | DNE | ||||

| Vallböhmer et al[32] | 2012 | Cologne (oesophageal) | Yes | TRG 1 and 2 | 85 | 53 | DNE | ||||

| Winkler et al[33] | 2012 | Dworak (rectal) | No | TRG 1 | 33 | 9 | DNE | ||||

| Elezkurtaj et al[20] | 2013 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 0,1 and 2 | 102 | 68 | |||||

| Hermanek et al[23] | 2013 | Rodel (rectal based on Wittekind and Tannapfel (rectal based on Dworak) | Yes | Categorised as poor according to Rodel and based on TRG 0and1 on Wittekind and Tannapfel (a modified Dworak scale) | 225 | 33 | 92 | 15.9 | 27.9 | Yr. 5: 63.6 | Yr. 5: 75.8 |

| Fokas et al[14] | 2014 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 0+1 | 386 | 90 | 132 | Yr. 10: 3.6 | Yr. 10: 39.6 | Yr. 10: 63% | |

| Santos et al[16] | 2014 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 0,1 and 2 | 144 | 85 | 56 | 3.5 | 16.4 | Yr. 5: 68.1 | Yr. 5: 69.1 |

| Santos et al[16] | 2014 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 3 and 4 and 5 | 144 | 69 | 56 | 4.3 | 20.3 | Yr. 5: 61.7 | Yr. 5: 60.7 |

| Hav et al[15] | 2015 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 0,1 and 2 | 76 | 48 | 20 | No specific data but no correlation with DFS |

Fourteen studies that defined poor response reported on outcomes (Table 5). LR at 5 years ranged from 2% to 26%[17,18,23,26,27,31], DR was 14.3% to 47%[18,23,26,27,31]. One study reported 10-year LR and DR of 3.6% and 39.6%, respectively[14]. Two-year DFS was 60.3% to 83.6%[19,29,31], 3-year DFS was 72.6% to 73.8%[30,31], 4-year DFS was reported by a single study as 47%[18], 5-year DFS was reported as 56% to 71%[13,16,17,23,26], and 10-year DFS was documented as 63%[14]. OS at 2 years was 87.3% to 92.6%[29] and at 5 years was 60.7% to 75.8%[16,23,26].

Six scales[18,25,35,40,43,44,46] were used in 20 reports (16 articles) to define good response[13-16,18,20,21,24-26,28-33]. These six scales produced 12 different definitions of good response (Table 2). The characteristics of these studies are shown in Table 1. Table 6 shows the scales defining good response along with their permutations.

| Ref. | Year | TRG scale used (original disease application) | Are the scales reported accurately? | Good response definition | Total (n) | Good responders (n) | Average F/up in months | LR (%) 5 yr | DR (%) 5 yr | DFS (%) | OS (%) |

| Gambacorta et al[21] | 2004 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 1 and 2 | 54 | 24 | 25 | ||||

| Pucciarelli et al[28] | 2004 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 1 and 2 and 3 | 104 | 52 | 42 | DNE | DNE | ||

| Horisberger et al[24] | 2008 | Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (rectal) | Yes | TRG 2 and 3 | 59 | 33 | |||||

| Suárez et al[31] | 2008 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 1 and 2 | 119 | 36 | 33 | 0 | 0 | DNE | |

| Bujko et al[18] | 2010 | Glynne Jones/Bujko (rectal) | Yes | TRG 1 | 131 | 40 | 48 | 9 | 34 | Yr. 4: 67 | |

| Avallone et al[13] | 2011 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 2 and 3 | 63 | 20 | 60 | Yr. 5: Prob free of recurrence > 90% | |||

| Shin et al[30] | 2011 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 1 and 2 and 3 | 102 | 52 | 40.3 | Yr. 3: 74.1 | |||

| Huebner et al[25] | 2012 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 2 and 3 and 4 | 237 | 176 | |||||

| Lim et al[26] | 2012 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 3 and 4 | 581 | 224 | 61 | 1.3 | 11.6 | Yr. 5: 86.7 | Yr. 5: 88.2 |

| Roy et al[29] | 2012 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 2 and 3 and 4 | 75 | 33 | Yr. 2: 91.7 | Yr. 2: 89.2 | |||

| Roy et al[29] | 2012 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 1 and 2 and 3 | 75 | 51 | Yr. 2: 86.1 | Yr. 2: 92.2 | |||

| Vallböhmer et al[32] | 2012 | Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (rectal) | Yes | TRG 3 | 85 | 23 | DNE | ||||

| Vallböhmer et al[32] | 2012 | Junker Miller (lung) | Yes | TRG 2aand2b | 85 | 65 | DNE | ||||

| Vallböhmer et al[32] | 2012 | Cologne (oesophageal) | Yes | TRG 3 and 4 | 85 | 26 | DNE | ||||

| Winkler et al[33] | 2012 | Dworak (rectal) | No | TRG 3 | 33 | 6 | |||||

| Elezkurtaj et al[20] | 2013 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 3 and 4 | 102 | 34 | |||||

| Fokas et al[14] | 2014 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 2 and 3 | 386 | 256 | 132 | Yr. 10: 8.0 | Yr. 10: 29.3 | Yr. 10: 73.6% | |

| Santos et al[16] | 2014 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 3 and 4 | 144 | 54 | 56 | 1.8 | 11.1 | Yr. 5: 78.4 | Yr. 5: 77.4 |

| Santos et al[16] | 2014 | Mandard (oesophagus) | Yes | TRG 1 and 2 | 144 | 70 | 56 | 1.4 | 8.6 | Yr. 5: 81.7 | Yr. 5: 79.4 |

| Hav et al[15] | 2015 | Dworak (rectal) | Yes | TRG 3 and 4 | 76 | 28 | 20 | No specific data but no correlation with DFS |

Ten studies reported on outcomes (Table 6). Most studies defined good response as Mandard 1 to 2, 1 to 3, 2 to 3 or Dworak 2 to 4, 3 to 4 or 2 to 3. LR at 5 years after a good response ranged from 0% to 9%[16,18,26,31] and DR was reported as 0% to 34%[16,18,26,31]. One study reported 10-year LR and DR of 8.0% and 29.3%, respectively[14]. Two-year DFS was 86.1% to 91.7%[29], 3-year DFS was 74.1%[30], 4-year DFS was 67%[18], 5-year DFS was 78.4% to > 90%[13,16,26], and 10-year DFS was 73.6%[14]. OS at 2 years was 89.2% to 92.2%[29], and at 5 years OS was 77.4% to 88.2%[16,26].

A range of survival outcomes existed for good and poor response (Table 7). There were 15 reports (11 articles) comparing outcomes from good and poor response[13-16,18,26,28-32]. Four outcome measures were examined in detail: LR, DR, DFS and OS.

| Ref. | Year | Good response defn. | Poor response defn. | LR % | P < 0.05 | DR % | P < 0.05 | DFS % | P < 0.05 | OS % | P < 0.05 | DSS | P < 0.05 | Conclusion | |||||

| GR | PR | GR | PR | GR | PR | GR | PR | GR | PR | ||||||||||

| Pucciarelli et al[28] | 2004 | TRG 1 and 2 and 3 | TRG 4 and 5 | Better in GR | No | Better in GR | No | Good responders have better, non-statistically significant outcomes for DFS and OS | |||||||||||

| Suárez et al[31] | 2008 | TRG 1 and 2 | TRG 3 and 4 and 5 | 0 | 3.4 | NC | 0 | 14.3 | NC | Better in GR | Yes | Better in GR | No | Good responders have better, statistically significant DFS but have better, non significant LR, DR and DSS | |||||

| Bujko et al[18] | 2010 | TRG 1 | TRG 3 | 9 | 26 | No | 34 | 47 | No | 67 | 47 | No | Good responders have better, non-statistically significant outcomes for LR, DR and DFS | ||||||

| Avallone et al[13] | 2011 | TRG 2 and 3 | TRG 4 and 5 | Prob > 90% | Prob 56% | Yes | Good responders have better, statistically significant DFS | ||||||||||||

| Shin et al[30] | 2011 | TRG 1 and 2 and 3 | TRG 4 and 5 | 74.1 | 72.6 | No | Good responders have better, non-statistically significant outcomes for DFS | ||||||||||||

| Lim et al[26] | 2012 | TRG 3 and 4 | TRG 1 and 2 | 1.3 | 9.5 | Yes | 11.6 | 27.2 | Yes | 86.7 | 63.6 | Yes | 88.2 | 71.3 | Yes | Good responders have better, statistically significant outcomes for LR, DR, DFS and OS | |||

| Roy et al[29] | 2012 | TRG 1 and 2 and 3 | TRG 4 and 5 | 86.1 | 60.3 | Yes | 92.2 | 87.3 | No | Good responders have better, statistically significant DFS but have better, non significant OS | |||||||||

| Roy et al[29] | 2012 | TRG 2 and 3 and 4 | TRG 0 and 1 | 91.7 | 68.9 | No | 89.2 | 92.6 | No | Good responders had better, non-statistically significant outcomes for DFS. Good responders had poorer, non-statistically significant outcomes for OS | |||||||||

| Vallböhmer et al[32] | 2012 | TRG 3 | TRG 1 | Better in GR | No | Good responders have better, non-statistically significant outcomes for OS | |||||||||||||

| Vallböhmer et al[32] | 2012 | TRG 2a and 2b | TRG 1 | Better in GR | No | Good responders have better, non-statistically significant outcomes for OS | |||||||||||||

| Vallböhmer et al[32] | 2012 | TRG 3 and 4 | TRG 1 and 2 | Better in GR | No | There was no statistically significant difference for OS between good and poor responders | |||||||||||||

| Fokas et al[14] | 2014 | TRG 2 and 3 | TRG 0 and 1 | 8 | 3.6 | No | 29.3 | 39.6 | Yes | 73.6 | 63 | Yes | Good responders have better, statistically significant outcomes for DR and DFS. Good responders had poorer, non-statistically significant outcomes for LR | ||||||

| Santos et al[16] | 2014 | TRG 1 and 2 | TRG 3 and 4 and 5 | 1.4 | 4.3 | NC | 8.6 | 20.3 | NC | 81.7 | 61.7 | Yes | 79.4 | 60.7 | Yes | Good responders have better, statistically significant outcomes for DFS and OS | |||

| Santos et al[16] | 2014 | TRG 3 and 4 | TRG 0 and 1 and 2 | 1.8 | 3.5 | NC | 11.1 | 16.4 | NC | 78.4 | 68.1 | No | 77.4 | 69.1 | No | Good responders have better, non-statistically significant outcomes for DFS and OS | |||

| Hav et al[15] | 2015 | TRG 3 and 4 | TRG 0 and 1 and 2 | Better in GR | No | Good responders have better, non-statistically significant outcomes for DFS | |||||||||||||

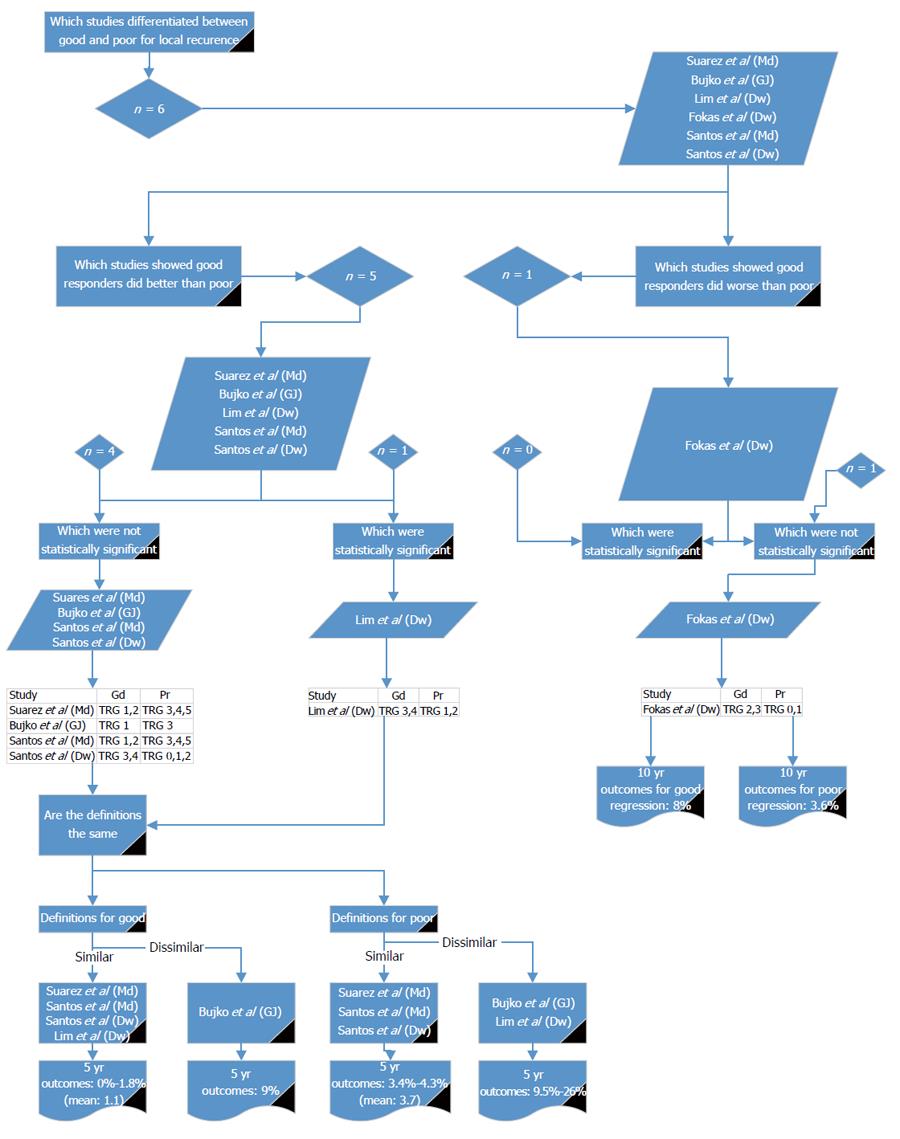

Six reports from five studies[14,16,18,26,31] compared good and poor response in relation to LR (Figure 2). Of these, one study reported a non-significantly higher LR in good responders compared with poor responders[14]. Five reports[16,18,26,31] showed LR was higher in poor responders, of which only one study showed a significant difference[26]. Using the definition given by Lim et al[26] there were three other studies with similar definitions[16,31]. The reported LR for good response ranged from 0% to 1.8%[16,26,31]. There were no studies that agreed with Lim et al[26] for the definition of poor response. Three studies[16,31] agreed with each other for poor response and reported LR of 3.4% to 4.3%. Lim et al[26] (which showed a significant difference between good and poor) gave LR rate in poor responders of 9.5%. This indicates that either Mandard 1 to 2 or Dworak 3 to 4 should be used to define good response for LR and Mandard 3 to 5 or Dworak 0 to 2 or 1 to 2 should be used for poor response.

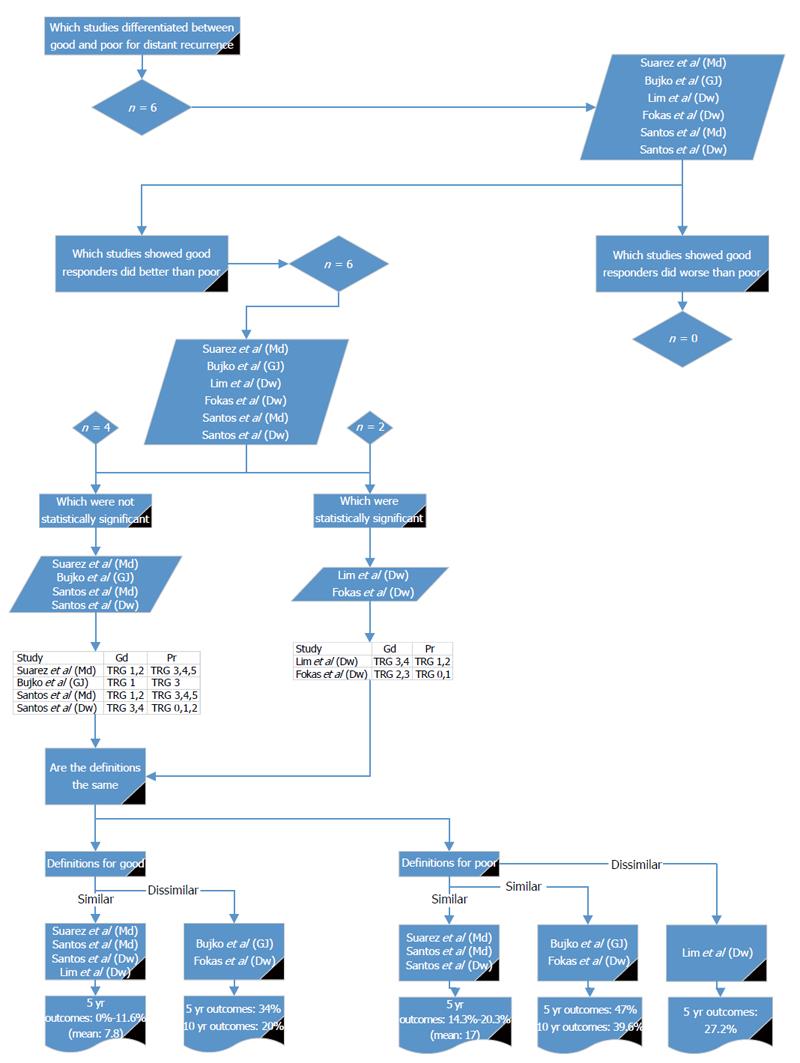

Six reports from five studies[14,16,18,26,31] compared good and poor response in relation to DR (Figure 3). Of these, all showed DR was higher in poor responders, of which two studies (Lim et al[26] and Fokas et al[14]) showed a significant difference; although, they used different definitions. Using the definition given by Lim et al[26], there were three other studies with similar definitions[16,31]; the reported 5-year DR for good response was 0% to 11.6%. Using the definition given by Fokas et al[14], there was one other study with a similar definition[18]; the reported 5- and 10-year DR for good response was 34% and 29%, respectively. Poor response was defined by three studies[16,31], with similar definitions reporting DR of 14.3% to 20.3%. Poor response was 47% and 39.6% for 5- and 10-year DR, respectively, by two other studies[14,18] with similar definitions. Lim et al[26] reported 5-year DR as 27.2% for poor responders. The values reported by Fokas et al[14] and Bujko et al[18] are much higher than the other reports and do not reflect the body of literature. It would, therefore, be preferable to use either Mandard 1 to 2 or Dworak 3 to 4 for defining good response for DR and Mandard 3 to 5 or Dworak 0 to 2 or 1 to 2 for poor response.

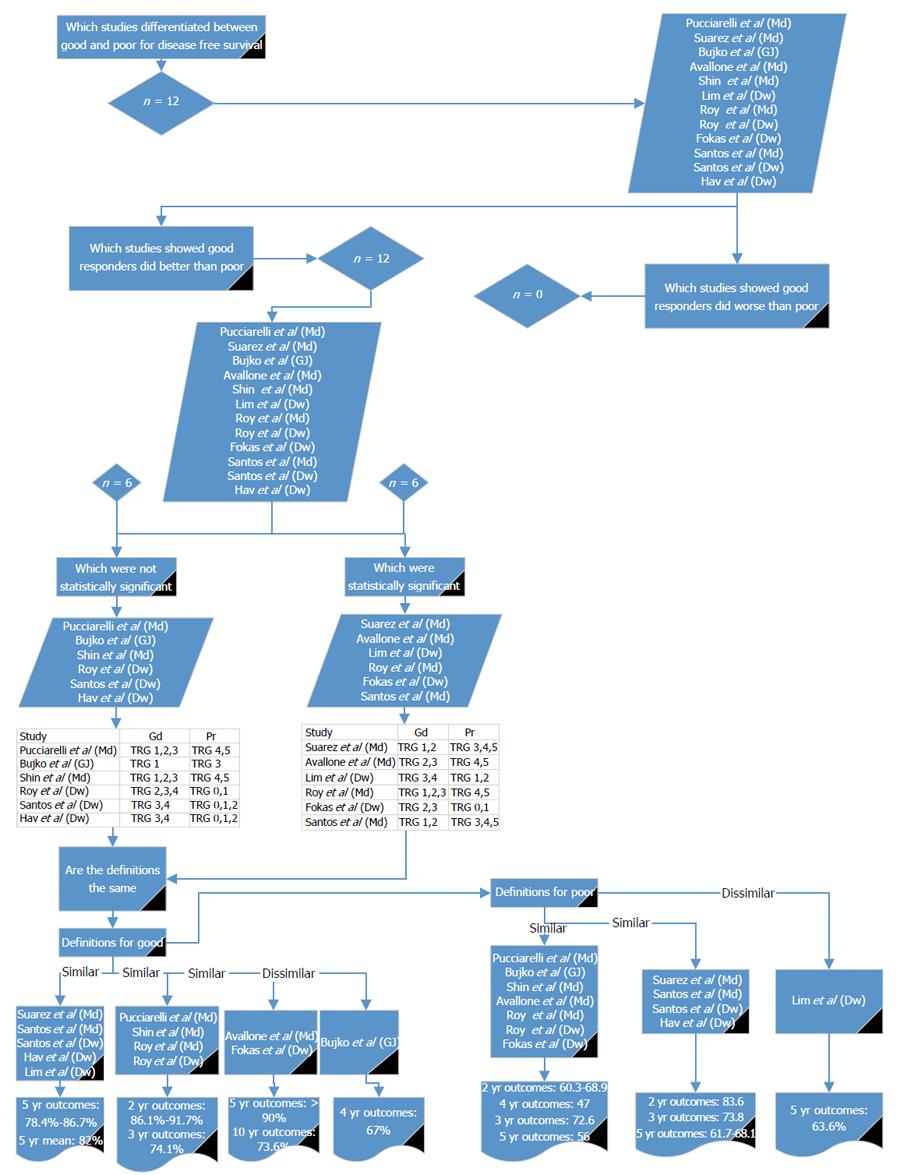

Twelve reports[13-16,18,26,28-31] compared good and poor response in relation to DFS (Figure 4). All of the studies showed DFS to be worse in poor responders. Six studies showed a significant difference between good and poor response[13,14,16,26,29,31]. For the definition of good response, three of the papers[16,26,31] showing a statistical significance used a similar definition to each other; two[13,14] used different definitions but were similar to each other and one used a different definition to the other significant studies[29]. Using the definition given by Lim et al[26] and comparing it to studies with similar definitions[15,16,30,31], the reported DFS for good response at 5 years was 78.4% to 86.7%. Using the definition given by Fokas et al[14] and comparing it with the other reports with similar definitions[13], the reported 5- and 10-year DFS for good response was > 90% and 73.6%, respectively. Using the definition by Roy et al[29] and comparing it with the other studies with similar definitions[28-30], 2-year DFS was 86.1% to 91.7% and 3-year DFS was 74.1%.

For the definition of poor response, three of the papers[13,14,29] showing a statistical significance used a similar definition to each other, two[16,31] used different definitions but were similar to each other and one study was different in its definition of poor response[26]. Using the definition given by Avallone et al[13] and comparing it to the other studies with similar definitions[14,18,28-30], the reported DFS for poor response at 2 years was 60.3% to 68.9%, at 3 years was 72.6%, at 4 years was 47%, and at 5 years was 56%. Using the definition given by Suárez et al[31] and comparing it with the other studies with similar definitions[15,16], the reported DFS for poor response at 2 years was 83.6%, at 3 years was 73.8%, and at 5 years was 61.7% to 68.1%. Lim et al[26] reports a 5-year DFS of 63.6%. From these results it may be appropriate to use Mandard 1 to 2, 1 to 3 or 2 to 3 or Dworak 3 to 4, 2 to 4 or 2 to 3 for defining good response and Mandard 4 to 5, 3 to 5 or Dworak 0 to 1, 0 to 2 or Bujko 3 to define poor response.

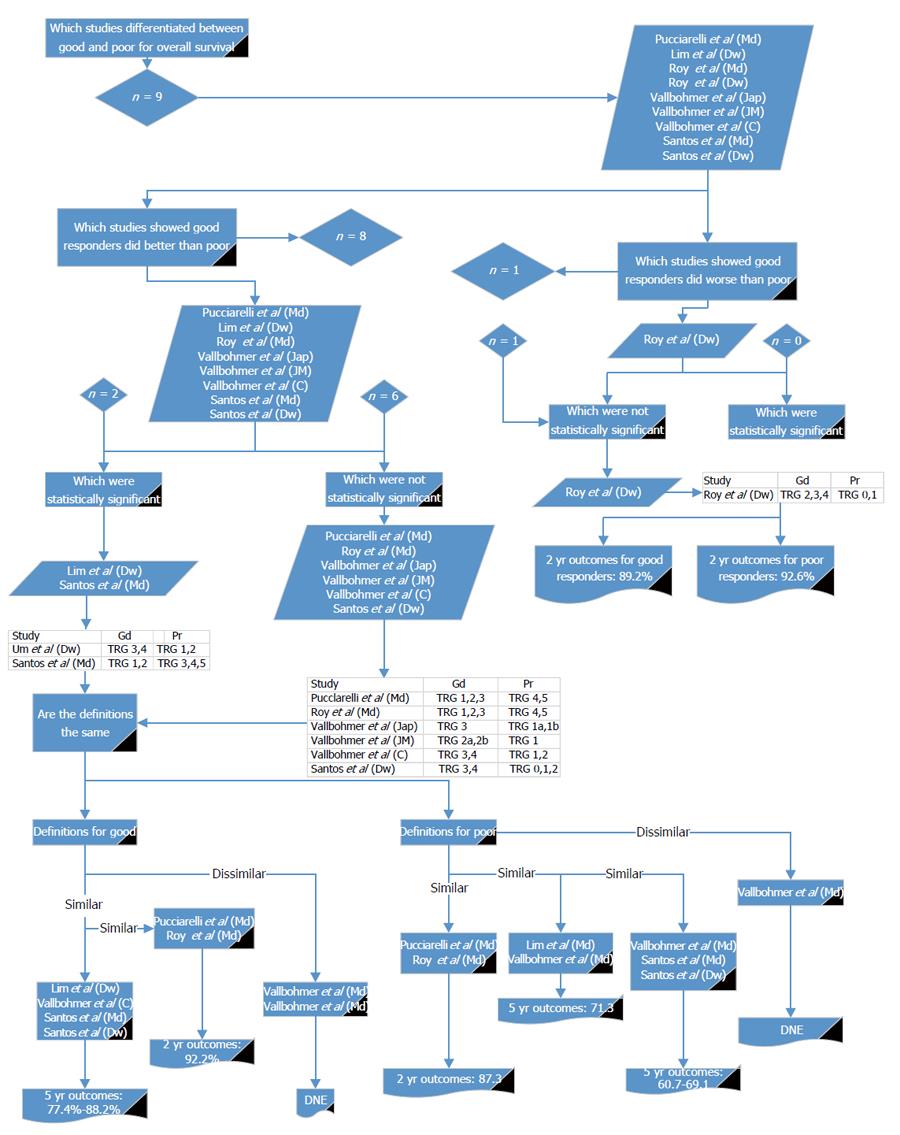

Nine reports[16,26,28,29,32] compared good and poor response in relation to OS (Figure 5). Of these, all but one[29] showed OS was non-significantly worse in poor responders. Six reports from four papers showed a significant difference[16,28,29,32]. For the definition of good response, two of the papers[16,32] showing a statistical significance used a similar definition to each other; two reports from one paper[32] used different definitions but were similar to each other, and a further two used similar definitions to each other but were different from the other papers[28,29]. Using the definition given by Pucciarelli et al[28] and comparing it with the other studies with similar definitions[29], the reported OS for good response at 2 years was 92.2%. Using the definition given by Lim et al[26] and comparing it with the other studies with similar definitions[16,26,32], the reported OS for good response at 5 years was 77.4% to 88.2%.

For the definition of poor response, two of the papers[28,29] showing a statistical significance used a similar definition to each other and a further two studies had similar definitions to each other[16,32]. Two reports from one study were different in their definitions of poor response[32]. Using the definition given by Pucciarelli et al[28] and comparing it with other reports with similar definitions[29], the reported OS for poor response was 87.3% at 2 years. Using the definition given by Vallböhmer et al[32] and comparing it with the studies with similar definitions[26], the reported OS for poor response was 71.3% at 5 years. Using the next definition given by Vallböhmer et al[32] and comparing it with studies with similar definitions[16], the reported OS for poor response was 60.7% to 69.1% at 5 years. From these results it may be appropriate to use Mandard 1 to 2, 1 to 3 or Dworak 3 to 4 or Cologne 3 to 4 for defining good response and Mandard 4 to 5, 3 to 5 or Dworak 0 to 2, 1 to 2 or Japanese 1a to 1b or Cologne 1 to 2 to define poor response.

These results show that across the outcomes of LR, DR, DFS and OS, Mandard 1 to 2 and Dworak 3 to 4 could be used for defining good response and Mandard 3 to 5 and Dworak 0 to 2 for poor response.

There was one mrTRG system using a 5-point scale[52] (Table 8). Lower mrTRG refers to greater regression and the system also divides the categories into type of response (complete, good, moderate, slight and none).

| mrTRG scale | mrTRG |

| (Low no. - More regression)[47] | |

| 1 | Radiological complete response: no evidence of ever treated tumour |

| 2 | Good response (dense fibrosis; no obvious residual tumour, signifying minimal residual disease or no tumour) |

| 3 | Moderate response (50% fibrosis or mucin, and visible intermediate signal) |

| 4 | Slight response (little areas of fibrosis or mucin but mostly tumour) |

| 5 | No response (intermediate signal intensity, same appearances as original tumour) |

There were five papers on five studies reporting on poor response[5-7,52,53]. Characteristics of these studies can be seen in Table 9. Overall, the reported proportion of poor responders after neo-adjuvant CRT was 38.6% (95%CI: 34.5%-42.8%) and there was only moderate heterogeneity that was still significant (Q = 10.7, df = 4, I2 = 63, P = 0.03) (Figure 6).

| Ref. | Year | Chemotherapy protocol | Radiotherapy protocol (Gy) | Surgical procedures | TME | Time to surgery (wk) | Cancer stage Pre neo-adjuvant therapy | Adjuvant therapy |

| Shihab et al[52] | 2011 | APR/AR | Y | |||||

| Patel et al[7] and Siddiqui et al[8] | 2011 and 2012 | APR/AR | Y | |||||

| Patel et al[6] | 2012 | APR/AR | Y | T1/2/3/4, N0/1/2 | Y | |||

| Yu[53] | 2014 (unpublished data from our centre) | Capecitabine, oxaliplatin ± cetuximab | 50.4-54 | Y | T2/3/4 | Y | ||

| Yu[53] | 2014 (unpublished data from our centre) | Capecitabine, oxaliplatin ± cetuximab | 50.4-54 | Y | T2/3/4 | Y |

Two studies[5-7] stated that mrTRG was based on the Dworak scale, but the hierarchy actually follows that of the Mandard scale (Table 10). Three studies stated that it was based on the Mandard scale[52,53]. Poor response was defined as mrTRG 4 and mrTRG 5 by all of the papers. LR for poor responders at 5 years ranged from 4% to 29%[6,52]. Five year DR was 9%[52]. From our centres, unpublished data for 3-year DFS was 52%[53] and 5-year DFS was 31% to 68%[6,53]. OS at 3 years from this centre was 74%[53] and at 5 years was 27% to 68%[6,53].

| Ref. | Year | TRG scale used (histological stage based upon) | Scales accurate? | Poor response definition | Total (n) | Poor responders (n) | Average F/up in months | LR (%) 5 yr | DR (%) 5 yr | DFS (%) | OS (%) |

| Shihab et al[52] | 2011 | MRI TRG (based on Mandard) | Yes | TRG 4,5 | 37 | 17 | 4 | 9 | |||

| Patel et al[5,7] | 2012 | MRI TRG (based on Dworak) | Yes | TRG 4,5 | 69 | 22 | |||||

| Patel et al[6] and Patel et al[7] | 2011 and 2012 | MRI TRG (based on Dworak) | Yes | TRG 4,5 | 66 | 34 | 60 | 29 | Yr. 5: 31 | Yr. 5: 27 | |

| Yu[53] | 2014 (unpublished data from our centre) | MRI TRG (based on Mandard and Dworak) | Yes | TRG 4,5 | 210 | 85 | Yr. 3: 52% | Yr. 3: 74% | |||

| Yu[53] | 2014 (unpublished data from our centre) | MRI TRG (based on Mandard and Dworak) | Yes | TRG 4,5 | 152 | 47 | Yr. 5: 59% | Yr. 5: 68% |

LR rates for good responders at 5 years ranged from 1% to 14%[6,52]. Five-year DR was 3%[52] and DFS was 64% to 83%[6,53]. OS at 5 years was 72% to 90%[6,53] (Table 11).

| Ref. | Year | TRG scale used (histological stage based upon) | Scales accurate? | Good response definition | Total (n) | Good responders (n) | Average F/up in months | LR (%) 5 yr | DR (%) 5 yr | DFS (%) | OS (%) |

| Shihab et al[52] | 2011 | MRI TRG (based on Mandard) | Yes | TRG 1,2,3 | 37 | 20 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Patel et al[6] | 2012 | MRI TRG (based on Dworak) | Yes | TRG 1,2,3 | 69 | 47 | |||||

| Patel et al[5] and Patel et al[7] | 2011 and 2012 | MRI TRG (based on Dworak) | Yes | TRG 1,2,3 | 66 | 32 | 60 | 14 | Yr. 5: 64 | Yr. 5: 72 | |

| Yu[53] | 2014 (unpublished data from our centre) | MRI TRG (based on Mandard and Dworak) | Yes | TRG 1,2 | 152 | 61 | DFS, Yr. 5: 83% | DFS, Yr. 5: 90% |

mrTRG is a relatively new scale and the studies reporting it are from one centre; hence, consistency would be expected. Good responders were defined as mrTRG 1 to 3 or 1 to 2 and poor responders were defined as mrTRG 4 to 5 (Table 12).

| Ref. | Year | Local recurrence (LR) | P < 0.05 | Distant recurrence (DR) | P < 0.05 | Progression disease-free survival (DFS) | P < 0.05 | Disease-free survival (DFS) | P < 0.05 | Overall survival (OS) | P < 0.05 | Conclusion |

| Shihab et al[52] | 2011 | Better in GR | No | Better in GR | Yes | Good responders have better, statistically significant outcomes for DR but have better, non significant LR | ||||||

| Patel et al[5] and Patel et al[7] | 2011 and 2012 | Better in GR | No | Better in GR | Yes | Better in GR | Yes | Good responders have better, statistically significant outcomes for DFS and OS but have better, non significant outcomes for LR | ||||

| Yu[53] | 2014 | Better in GR | Yes | Better in GR | Yes | Good responders have better, statistically significant outcomes for DFS and OS |

There are three articles with available data comparing outcomes for good and poor responders (Table 11). In all three reports, good responders had better outcomes compared with poor responders in relation to LR, DR, DFS and OS. Furthermore in all but LR there was a statistically significant difference in outcomes.

Although there was a range of survival outcomes, the overall rates for survival are lower in poor responders, distinguishing them clearly from the survival figures and rates of those with good response.

From these results, good response may be defined as mrTRG 1 to 3 or 1 to 2 (with mrTRG3 as a separate, independent group) and poor responders as mrTRG 4 to 5. This consistency of results, therefore, indicates the secondary hypothesis is likely to be true.

Publication bias for prevalence from histology was initially assessed using a funnel plot (Figure 7). There appeared to be some asymmetry on the plot and so Eggers test was used. There was statistically significant asymmetry seen (Intercept: -4.30, SE: 2.23, 95%CI:-8.90-0.31, t = 1.93, P = 0.07), indicating there is unlikely to be significant publication bias.

The senior author (GB) was supported by a grant from the Royal Marsden Hospital National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research. JB was supported by a fellowship from the Royal College of Surgeons, England. The centre and a co-author (NPW) was supported by the Yorkshire Cancer Research and Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. The funders played no role in the study design, analysis or writing of the manuscript and accept no responsibility for its content.

The aim of this review was to investigate the range and method of how poor response to neo-adjuvant therapy for rectal cancer is defined in order to see which scale best distinguishes between the two groups in relation to outcomes.

In summary, this paper has shown that across the outcomes of LR, DR, DFS and OS, Mandard 1, 2 and Dworak 3, 4 could be used for defining good response and Mandard 3, 4, 5 and Dworak 0, 1, 2 for defining poor response. There are other definitions shown above which may also differentiate good and poor response. The analysis has shown differences in the reliability of these scales in consistently identifying good and poor responders.

Our results have shown that there are three major challenges when it comes to the standardization of tumour regression for rectal cancer. The first is the vast choice of regression scales available to histopathologists. The second is that studies use these varied scales to define poor response without consistency. The third is that there are marked differences between the scales. Therefore, trying to merge these systems into one, universally acceptable scale becomes unrealistic. Furthermore, studies have shown that inter-observer agreement amongst histopathologists using the existing scales is low[54]. The scales themselves do not advise on whether histopathologists should use a single worst slide for assessment or a composite assessment and adds to the challenge of defining good and poor response. This was highlighted by a study which showed poor inter-observer agreement between histopathologists assessing regression using different regression scales[54].

Some of the scales use qualitative estimates[25,39,46] for levels of fibrosis, but these overlap with regression grades in alternative scales given in other studies[35,43]. Even by trying to examine the correlation between two systems, two grades may be grouped into one grade on a different scale.

Both MRI and histopathological grading systems are open for misinterpretation if standard methods of preparation and interpretation are not employed; there has been a focused attempt to do this in relation to histopathological assessment[54,55] and mrTRG is a novel scale requiring appropriate training to ensure consistency when utilised in other centres.

Differences in the definitions of poor response are highlighted by the number of poor responders identified in each of the studies (Figures 1 and 6). This review concentrated on studies using specific terms stating what they believed to be poor response; however, there were studies that divided TRG into two groups but did not specifically state them as good and poor responders; their results are consistent with the range that is reported in this paper but differ in that they show a good correlation to outcomes for their presumed good and poor responders[56].

In relation to the original definitions, one study showed that poor responders could be either those with predominant fibrosis or patients with tumour outgrowing fibrosis[31] compared with other studies using the same Mandard scale which only defined poor responders as those with tumour outgrowing fibrosis[22]. This is then compounded by the fact that more than one grade on other scales could be combined together on an alternative system.

Historically, the histopathological TRG systems were developed without validation of the grading in relation to outcomes, and evolution of these scales has occurred with the presence of long-term prognostic information. Histopathological TRG is also dependent on thorough pathological sampling and comparisons are not made to the pre-treatment biopsy; therefore, high stromal content tumours are often given a better regression grade, even though the high stroma may not be due to regression. mrTRG may be one way to respond to this, as it compares and examines the whole tumour and because of the presence of one-scale heterogeneity is reduced. mrTRG also better distinguishes between good and poor response in relation to survival. LR appears to be reported with a large range using both histopathological and mrTRG and may relate to surgical factors being the most important issue in relation to this outcome.

Recent data from our centre would suggest that mrTRG3, whilst traditionally considered a good response, behaves more like the poor responder group[57] and could be considered as a separate group[58].

In summary, this paper has shown that across the outcomes of LR, DR, DFS and OS, Mandard 1 to 2 and Dworak 3 to 4 could be used for defining good response and Mandard 3 to 5 and Dworak 0 to 2 for poor response. These definitions may help in achieving consensus in histopathological reporting. However, these definitions do not always produce a significant difference in the outcomes from the different studies utilizing these definitions. Furthermore, there are other definitions shown above which may also differentiate good and poor response. This casts doubt on the reliability of these scales in consistently identifying good and poor responders. A preoperative grading system, such as mrTRG, may be useful to appropriately differentiate good and poor response, thus guiding management decisions, and images attained could effectively be attained by high resolution MRI imaging.

A range of histopathological TRG scales is used in clinical studies. Good and poor response are heterogeneously described, even when using the same histopathological regression scales. Across the outcomes of LR, DR, DFS and OS, Mandard 1 to 2 and Dworak 3 to 4 could be used for defining good response and Mandard 3 to 5 and Dworak 0 to 2 for poor response. These definitions may help in achieving consensus in histopathological reporting. Preoperative mrTRG is similarly able to differentiate between good and poor response based on outcomes.

We acknowledge support from Lisa Scerri.

Clinical studies use a number of different tumour regression grade (pTRG) scales to classify the degree of tumour response to neo-adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy (CRT). This often results in confusion as to whether a good or poor response has been achieved, with subsequent uncertainty regarding treatment and prognostic implications. This problem was highlighted by studies that stress the importance of a universally accepted standard. There has been no review of the reported pTRG scales to date. It is necessary to highlight the heterogeneity in these scales, consolidate the current definitions with the purpose of converging towards a set of consensus definitions. This article investigates all the pathology tumour regression scales used to define good and poor response after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for rectal cancer, to establish the true prevalence of poor responders and to identify the best scales to use in relation to outcomes.

A newer method of assessing tumour regression relies on MRI (mrTRG), which has been validated as a prognostic tool. This may supercede pTRG, as it has the advantage of assessing tumour response before surgery. Potential enabling response-orientated tailored treatment, including alteration of the surgical planes, additional use of chemotherapy or deferral of surgery.

The authors have found the best classification of good and poor response for rectal cancer response to neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy.

This systematic review has immediate application to rectal cancer care by identifying how to classify good and poor response in the context of outcomes of local recurrence, metastases, disease-free survival and overall survival

This is an interesting review about neoadjuvant therapy for postoperative outcome in rectal cancer.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Korkeila E, Paydas S, Rafaelsen SR S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | MacGregor TP, Maughan TS, Sharma RA. Pathological grading of regression following neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy: the clinical need is now. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:867-871. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chua YJ, Barbachano Y, Cunningham D, Oates JR, Brown G, Wotherspoon A, Tait D, Massey A, Tebbutt NC, Chau I. Neoadjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin before chemoradiotherapy and total mesorectal excision in MRI-defined poor-risk rectal cancer: a phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:241-248. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 247] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Marijnen CA, Glimelius B. The role of radiotherapy in rectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:943-952. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Påhlman L, Hohenberger W, Günther K, Fietkau R, Metzger U. Is radiochemotherapy necessary in the treatment of rectal cancer? Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:438-448. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Patel UB, Blomqvist LK, Taylor F, George C, Guthrie A, Bees N, Brown G. MRI after treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer: how to report tumor response--the MERCURY experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:W486-W495. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 137] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Patel UB, Brown G, Rutten H, West N, Sebag-Montefiore D, Glynne-Jones R, Rullier E, Peeters M, Van Cutsem E, Ricci S. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and histopathological response to chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2842-2852. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 159] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Patel UB, Taylor F, Blomqvist L, George C, Evans H, Tekkis P, Quirke P, Sebag-Montefiore D, Moran B, Heald R. Magnetic resonance imaging-detected tumor response for locally advanced rectal cancer predicts survival outcomes: MERCURY experience. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3753-3760. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 446] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Siddiqui MRS. How is good and poor response to neoadjuvant therapy defined using histological and MRI regression scales in rectal cancer studies with reference to outcomes. PROSPERO 2016: CRD42016032587. Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016032587. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Rullier A, Laurent C, Capdepont M, Vendrely V, Bioulac-Sage P, Rullier E. Impact of tumor response on survival after radiochemotherapy in locally advanced rectal carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:562-568. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H, editor . Comprehensive Meta-analysis Version 2. Available from: http://www.doc88.com/p-030414137867.html. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. London: BMJ Publication group 2001; . [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Barker A, Maratos EC, Edmonds L, Lim E. Recurrence rates of video-assisted thoracoscopic versus open surgery in the prevention of recurrent pneumothoraces: a systematic review of randomised and non-randomised trials. Lancet. 2007;370:329-335. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Avallone A, Delrio P, Pecori B, Tatangelo F, Petrillo A, Scott N, Marone P, Aloi L, Sandomenico C, Lastoria S. Oxaliplatin plus dual inhibition of thymidilate synthase during preoperative pelvic radiotherapy for locally advanced rectal carcinoma: long-term outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:670-676. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fokas E, Liersch T, Fietkau R, Hohenberger W, Beissbarth T, Hess C, Becker H, Ghadimi M, Mrak K, Merkel S. Tumor regression grading after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal carcinoma revisited: updated results of the CAO/ARO/AIO-94 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1554-1562. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 284] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hav M, Libbrecht L, Geboes K, Ferdinande L, Boterberg T, Ceelen W, Pattyn P, Cuvelier C. Prognostic value of tumor shrinkage versus fragmentation following radiochemotherapy and surgery for rectal cancer. Virchows Arch. 2015;466:517-523. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Santos MD, Silva C, Rocha A, Matos E, Nogueira C, Lopes C. Prognostic value of mandard and dworak tumor regression grading in rectal cancer: study of a single tertiary center. ISRN Surg. 2014;2014:310542. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Beddy D, Hyland JM, Winter DC, Lim C, White A, Moriarty M, Armstrong J, Fennelly D, Gibbons D, Sheahan K. A simplified tumor regression grade correlates with survival in locally advanced rectal carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3471-3477. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 118] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bujko K, Kolodziejczyk M, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A, Michalski W, Kepka L, Chmielik E, Wojnar A, Chwalinski M. Tumour regression grading in patients with residual rectal cancer after preoperative chemoradiation. Radiother Oncol. 2010;95:298-302. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Eich HT, Stepien A, Zimmermann C, Hellmich M, Metzger R, Hölscher A, Müller RP. Neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy and surgery for advanced rectal cancer: prognostic significance of tumor regression. Strahlenther Onkol. 2011;187:225-230. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Elezkurtaj S, Moser L, Budczies J, Müller AJ, Bläker H, Buhr HJ, Dietel M, Kruschewski M. Histopathological regression grading matches excellently with local and regional spread after neoadjuvant therapy of rectal cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2013;209:424-428. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gambacorta MA, Valentini V, Morganti AG, Mantini G, Miccichè F, Ratto C, Di Miceli D, Rotondi F, Alfieri S, Doglietto GB. Chemoradiation with raltitrexed (Tomudex) in preoperative treatment of stage II-III resectable rectal cancer: a phase II study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:130-138. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Giralt J, Tabernero J, Navalpotro B, Capdevila J, Espin E, Casado E, Mañes A, Landolfi S, Sanchez-Garcia JL, de Torres I. Pre-operative chemoradiotherapy with UFT and Leucovorin in patients with advanced rectal cancer: a phase II study. Radiother Oncol. 2008;89:263-269. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hermanek P, Merkel S, Hohenberger W. Prognosis of rectal carcinoma after multimodal treatment: ypTNM classification and tumor regression grading are essential. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:559-566. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Horisberger K, Hofheinz RD, Palma P, Volkert AK, Rothenhoefer S, Wenz F, Hochhaus A, Post S, Willeke F. Tumor response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation in rectal cancer: predictor for surgical morbidity? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:257-264. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Huebner M, Wolff BG, Smyrk TC, Aakre J, Larson DW. Partial pathologic response and nodal status as most significant prognostic factors for advanced rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy. World J Surg. 2012;36:675-683. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lim SB, Yu CS, Hong YS, Kim TW, Park JH, Kim JH, Kim JC. Failure patterns correlate with the tumor response after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:667-673. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Min BS, Kim NK, Pyo JY, Kim H, Seong J, Keum KC, Sohn SK, Cho CH. Clinical impact of tumor regression grade after preoperative chemoradiation for locally advanced rectal cancer: subset analyses in lymph node negative patients. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2011;27:31-40. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pucciarelli S, Toppan P, Friso ML, Russo V, Pasetto L, Urso E, Marino F, Ambrosi A, Lise M. Complete pathologic response following preoperative chemoradiation therapy for middle to lower rectal cancer is not a prognostic factor for a better outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1798-1807. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 129] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Roy P, Serra S, Kennedy E, Chetty R. The prognostic value of grade of regression and oncocytic change in rectal adenocarcinoma treated with neo-adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:130-134. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shin JS, Jalaludin B, Solomon M, Hong A, Lee CS. Histopathological regression grading versus staging of rectal cancer following radiotherapy. Pathology. 2011;43:24-30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Suárez J, Vera R, Balén E, Gómez M, Arias F, Lera JM, Herrera J, Zazpe C. Pathologic response assessed by Mandard grade is a better prognostic factor than down staging for disease-free survival after preoperative radiochemotherapy for advanced rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:563-568. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 100] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Vallböhmer D, Bollschweiler E, Brabender J, Wedemeyer I, Grimminger PP, Metzger R, Schröder W, Gutschow C, Hölscher AH, Drebber U. Evaluation of histological regression grading systems in the neoadjuvant therapy of rectal cancer: do they have prognostic impact? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1295-1301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Winkler J, Zipp L, Knoblich J, Zimmermann F. Simultaneous neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy with capecitabine and oxaliplatin for locally advanced rectal cancer. Treatment outcome outside clinical trials. Strahlenther Onkol. 2012;188:377-382. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wheeler JM, Warren BF, Mortensen NJ, Ekanyaka N, Kulacoglu H, Jones AC, George BD, Kettlewell MG. Quantification of histologic regression of rectal cancer after irradiation: a proposal for a modified staging system. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1051-1056. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 148] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Dworak O, Keilholz L, Hoffmann A. Pathological features of rectal cancer after preoperative radiochemotherapy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1997;12:19-23. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 995] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1015] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 36. | Rödel C, Martus P, Papadoupolos T, Füzesi L, Klimpfinger M, Fietkau R, Liersch T, Hohenberger W, Raab R, Sauer R. Prognostic significance of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8688-8696. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 918] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 923] [Article Influence: 48.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ryan R, Gibbons D, Hyland JM, Treanor D, White A, Mulcahy HE, O’Donoghue DP, Moriarty M, Fennelly D, Sheahan K. Pathological response following long-course neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Histopathology. 2005;47:141-146. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 434] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Wittekind C, Tannapfel A. [Regression grading of colorectal carcinoma after preoperative radiochemotherapy. An inventory]. Pathologe. 2003;24:61-65. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Ruo L, Tickoo S, Klimstra DS, Minsky BD, Saltz L, Mazumdar M, Paty PB, Wong WD, Larson SM, Cohen AM. Long-term prognostic significance of extent of rectal cancer response to preoperative radiation and chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 2002;236:75-81. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 224] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Schneider PM, Baldus SE, Metzger R, Kocher M, Bongartz R, Bollschweiler E, Schaefer H, Thiele J, Dienes HP, Mueller RP. Histomorphologic tumor regression and lymph node metastases determine prognosis following neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for esophageal cancer: implications for response classification. Ann Surg. 2005;242:684-692. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 287] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Werner M, Hofler H. Pathologie. In: Roder JD, Stein HJ, Fink U, editors. Therapie gastrointestinaler Tumoren. Springer 2000; 45-63. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese classification of colorectal carcinoma, 1st English ed. Tokyo: Kanehara and Co 1997; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | Mandard AM, Dalibard F, Mandard JC, Marnay J, Henry-Amar M, Petiot JF, Roussel A, Jacob JH, Segol P, Samama G. Pathologic assessment of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy of esophageal carcinoma. Clinicopathologic correlations. Cancer. 1994;73:2680-2686. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Glynne-Jones R, Anyamene N. Just how useful an endpoint is complete pathological response after neoadjuvant chemoradiation in rectal cancer? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:319-320. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Bateman AC, Jaynes E, Bateman AR. Rectal cancer staging post neoadjuvant therapy--how should the changes be assessed? Histopathology. 2009;54:713-721. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Junker K, Müller KM, Bosse U, Klinke F, Heinecke A, Thomas M. Apoptosis and tumor regression in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer with neoadjuvant therapy. Pathologe. 2003;24:214-219. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 47. | Quah HM, Chou JF, Gonen M, Shia J, Schrag D, Saltz LB, Goodman KA, Minsky BD, Wong WD, Weiser MR. Pathologic stage is most prognostic of disease-free survival in locally advanced rectal cancer patients after preoperative chemoradiation. Cancer. 2008;113:57-64. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 194] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors . AJCC cancer staging manual. New York, NY: Springer 2010; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 49. | Swellengrebel HA, Bosch SL, Cats A, Vincent AD, Dewit LG, Verwaal VJ, Nagtegaal ID, Marijnen CA. Tumour regression grading after chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: a near pathologic complete response does not translate into good clinical outcome. Radiother Oncol. 2014;112:44-51. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Washington MK, Berlin J, Branton PA, Burgart LJ, Carter DK, Fitzgibbons PL, Frankel WL, Jessup JM, Kakar S, Minsky B. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with primary carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1182-1193. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Dhadda AS, Bessell EM, Scholefield J, Dickinson P, Zaitoun AM. Mandard tumour regression grade, perineural invasion, circumferential resection margin and post-chemoradiation nodal status strongly predict outcome in locally advanced rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2014;26:197-202. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Shihab OC, Taylor F, Salerno G, Heald RJ, Quirke P, Moran BJ, Brown G. MRI predictive factors for long-term outcomes of low rectal tumours. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:3278-3284. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Yu S. Outcomes of patients with rectal cancer according to tumour regression defined by MRI. : Personal communication 2013; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 54. | Chetty R, Gill P, Govender D, Bateman A, Chang HJ, Deshpande V, Driman D, Gomez M, Greywoode G, Jaynes E. International study group on rectal cancer regression grading: interobserver variability with commonly used regression grading systems. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:1917-1923. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Chetty R, Gill P, Govender D, Bateman A, Chang HJ, Driman D, Duthie F, Gomez M, Jaynes E, Lee CS. A multi-centre pathologist survey on pathological processing and regression grading of colorectal cancer resection specimens treated by neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Virchows Arch. 2012;460:151-155. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Vecchio FM, Valentini V, Minsky BD, Padula GD, Venkatraman ES, Balducci M, Miccichè F, Ricci R, Morganti AG, Gambacorta MA. The relationship of pathologic tumor regression grade (TRG) and outcomes after preoperative therapy in rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:752-760. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 311] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Yu S, Tait D, Brown G. The prognostic relevance of MRI Tumor Regression Grade versus histopathological complete response in rectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:iv114. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Using the magnetic resonance tumour regression grade (mrTRG) as a novel biomarker to stratify between good and poor responders following chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer: a multicentre randomised control trial. Available from: http://www.pelicancancer.org/bowel-cancer-research/trigger. [Cited in This Article: ] |