Published online Apr 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i14.3860

Peer-review started: November 16, 2015

First decision: December 11, 2015

Revised: December 22, 2015

Accepted: January 30, 2016

Article in press: January 31, 2016

Published online: April 14, 2016

AIM: To define the cost-effectiveness of strategies, including endoscopy and immunosuppression, to prevent endoscopic recurrence of Crohn’s disease following intestinal resection.

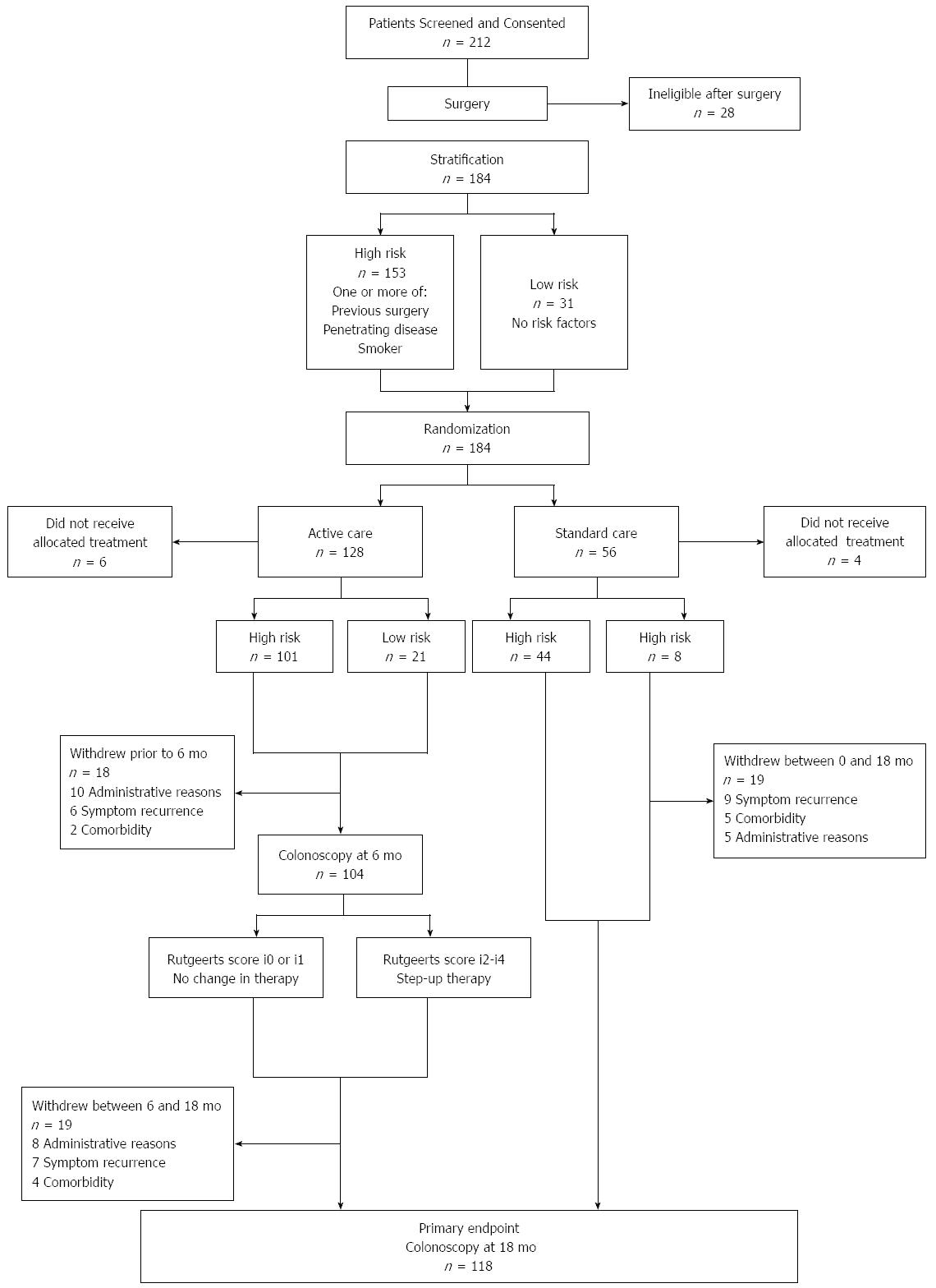

METHODS: In the “POCER” study patients undergoing intestinal resection were treated with post-operative drug therapy. Two thirds were randomized to active care (6 mo colonoscopy and drug intensification for endoscopic recurrence) and one third to drug therapy without early endoscopy. Colonoscopy at 18 mo and faecal calprotectin (FC) measurement were used to assess disease recurrence. Administrative data, chart review and patient questionnaires were collected prospectively over 18 mo.

RESULTS: Sixty patients (active care n = 43, standard care n = 17) were included from one health service. Median total health care cost was $6440 per patient. Active care cost $4824 more than standard care over 18 mo. Medication accounted for 78% of total cost, of which 90% was for adalimumab. Median health care cost was higher for those with endoscopic recurrence compared to those in remission [$26347 (IQR 25045-27485) vs $2729 (IQR 1182-5215), P < 0.001]. FC to select patients for colonoscopy could reduce cost by $1010 per patient over 18 mo. Active care was associated with 18% decreased endoscopic recurrence, costing $861 for each recurrence prevented.

CONCLUSION: Post-operative management strategies are associated with high cost, primarily medication related. Calprotectin use reduces costs. The long term cost-benefit of these strategies remains to be evaluated.

Core tip: The health care costs of a proactive disease-prevention post-operative Crohn’s disease strategy are substantial. Much of this cost relates to drug therapy (biologics). Active care involving endoscopic monitoring for disease recurrence, costs more than symptom-based monitoring. The occurrence of endoscopic recurrence increases costs significantly, related largely to drug therapy. Faecal calprotectin to monitor for disease recurrence can substantially decrease post-operative costs.

- Citation: Wright EK, Kamm MA, Dr Cruz P, Hamilton AL, Ritchie KJ, Bell SJ, Brown SJ, Connell WR, Desmond PV, Liew D. Cost-effectiveness of Crohn’s disease post-operative care. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(14): 3860-3868

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i14/3860.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i14.3860

Crohn’s disease is a chronic, relapsing, progressive inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. Annual direct medical costs are high, estimated at $4466 US dollars per patient per year[1], and exceed those required for the care of patients with ulcerative colitis. Costs are higher among those with active, severe, stricturing and/or penetrating disease and those requiring hospitalization, surgery, or therapy with glucocorticoids, immunosuppressives or biologic therapy[1-7].

Seventy percent of patients with Crohn’s disease need an intestinal resection at some time[8-11]. Within one year of surgery, subclinical endoscopic recurrence occurs at the anastomosis in 90% of patients, symptomatic clinical recurrence occurs in 30%, and 5% of patients undergo further surgical intervention[12-14]. Seventy percent of patients who have had an operation will ultimately require further surgery[8,15]. Treatment with thiopurines and/or anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents has been associated with a reduction in endoscopic recurrence[16-19].

Thiopurines are associated with significant cost savings when used for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, especially when used with pharmacogenetic testing of thiopurine s-methyltransferase and metabolite monitoring[20,21]. Anti-TNF drugs in Crohn’s disease are clinically effective[22,23]. But their cost-effectiveness has not been established with certainty. These agents reduce the costly complications of Crohn’s disease such as surgery and hospitalization, especially in the short term[24] and appear to be cost-effective when disease is severe or active[25-27]. However, the cost-effectiveness of long term maintenance treatment with infliximab or adalimumab is not known[25,28] although costs with adalimumab are less than those associated with infliximab therapy largely because of reduced infusion centre costs[29].

When considering the cost-effectiveness of drug strategies for the prevention of post-operative clinical recurrence, Ananthakrishnan et al[30] found that antibiotics were the most cost-effective option. They found that immediate therapy with infliximab post-operatively was not cost-effective, even in patients at high risk of early recurrence, although could be cost-effective if reserved for patients with early endoscopic recurrence at 6 mo. Doherty and colleagues[31] found that compared to no prophylactic treatment, prophylactic post-operative thiopurine therapy was the most cost-effective up to 1 year post-operatively, but at 5 years, mesalazine treatment was most favourable. However, endoscopic recurrence was not a factor in the primary model of these studies.

While these studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of prophylactic drug treatments post-operatively, there has been no detailed analysis to date of the cost-effectiveness of management strategies following intestinal resection, which include early endoscopic assessment, tailored drug therapy according to risk of recurrence, and the presence or absence of early endoscopic recurrence.

The Post-Operative Crohn’s Endoscopic Recurrence (POCER) study compared strategies to prevent endoscopic recurrence, taking into account risk of recurrence, efficacy of different drug regimens, and assessment of the benefit of endoscopic monitoring and treatment intensification providing a strategy for management of Crohn’s disease after intestinal resection[17]. This study also evaluated the efficacy of faecal calprotectin testing to detect early recurrent disease[32]. In a subset of patients from the POCER study, we aimed to undertake a detailed health care utilization and cost analysis to estimate health care costs associated with post-operative Crohn’s disease care and to estimate the cost-effectiveness of one management strategy over another.

The POCER study[1] was a prospective randomized control trial which assessed the efficacy of post-operative endoscopic assessment and treatment step-up for early mucosal recurrence. Patients were stratified according to risk of recurrence. Smokers, patients with perforating disease, or patients with ≥ 1 previous resections were classified as “high-risk”; all others “low-risk”. All patients underwent resection of all macroscopic disease and then received 3 mo of metronidazole. High-risk patients also received daily azathioprine (2 mg/kg per day) or 6-mercaptopurine (1.5 mg/kg per day). High-risk patients intolerant of thiopurine received adalimumab induction (160 mg/80 mg) and then 40 mg two-weekly. Low-risk patients received no further medication.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to colonoscopy at 6 mo (active care) or no colonoscopy (standard care). For endoscopic recurrence (Rutgeerts score ≥ i2) at 6 mo, patients stepped-up to thiopurine, fortnightly adalimumab with thiopurine, or weekly adalimumab. The primary end-point was endoscopic recurrence at 18 mo. Endoscopic remission was defined as Rutgeert’s score i0 or i1 (i0 = no lesions, i1 = mild small superficial anastomotic lesions), and recurrence defined as i2, i3 or i4 (moderate to severe lesions).

One hundred and seventy four patients were included at 17 hospitals in Australia and New Zealand. One hundred and one of 122 patients randomized to endoscopic intervention (6 mo colonoscopy) were high-risk, compared to 44 of 56 in the standard care arm (Figure 1). Key findings from the POCER study were: (1) treatment according to clinical risk of recurrence, with early colonoscopy and treatment step-up for recurrence, was better than conventional drug therapy alone for prevention of postoperative Crohn's disease recurrence; and (2) selective immune suppression, adjusted for early recurrence, rather than routine use, led to disease control in most patients. The study showed that while clinical risk factors, including smoking, could predict recurrence, patients at low risk of recurrence also benefited from monitoring and that early remission did not preclude the need for ongoing monitoring.

The present study comprised the subset of 60 patients from the POCER study with complete health care utilization and costing data, and complete post-operative follow-up for 6 mo or more. These patients’ post-operative care had been undertaken in one health service, St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne (SVHM), ensuring complete and consistent data capture. A minimum of 6 mo follow-up was chosen for patient inclusion, as this was the first endoscopic assessment point for patients in the study.

At ileo-colonoscopy, mucosal recurrence at the anastomosis and neo-terminal ileum was assessed according to the Rutgeerts score[13] by the endoscopist, who was aware of the patient’s treatment. At the 6 and 18 mo colonoscopies, endoscopic remission was defined as Rutgeerts score i0 (no lesions) or i1 (≤ 5 aphthous lesions) and recurrence as i2 (> 5 aphthous lesions or larger lesions confined to anastomosis), i3 (diffuse ileitis), or i4 (diffuse inflammation with large ulcers and/or narrowing)[13].

Patients completed health care utilization and work productivity questionnaires pre-operatively (baseline) and at 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 15 and 18 mo post-operatively. The data extracted is shown in Table 1.

| Health care utilization data extracted for health economic assessment |

| Number and type of consultations with gastroenterologists or other medical specialists for reasons related to Crohn’s disease. |

| Visits to primary care providers (general practitioners). |

| Visits to allied health care providers |

| Investigations related to Crohn’s disease |

| Visits to the emergency department |

| Hospital admissions < 1 d (day procedures) |

| Hospital admission ≥ 1 d |

| Current prescription medicine use related to Crohn’s disease |

Costs were stratified into the following categories: all drugs, adalimumab, inpatient care, in-hospital procedures (colonoscopy and iron infusion), emergency department attendances, specialist outpatient visits, outpatient allied health visits, primary care visits, outpatient medical imaging and pathology investigations.

Hospital cost data were derived from administrative databases maintained by the Clinical Costing Unit at SVHM, which routinely tracks all services provided to individual inpatients and assigns relevant service costs. Services comprise specific individualized items such as medical imaging, pharmacy, pathology, and surgical procedures, including operating room time, as well as more general care, such as time spent as an in-patient and consultation by medical, nursing, and allied health staff. This method of costing is known as the “bottom-up” approach[33].

Outpatient health care resource costs were estimated by multiplying episodes of care by unit costs. Episodes of care were derived from questionnaire data. Unit costs for medications and medical services were based on the Australian Medical Services Schedule[34] and Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule[35] respectively. All costs were from the perspective of the Australian public healthcare system, which funds the majority of healthcare in Australia. Therefore, cost estimates excluded any patient contribution.

All cost data were considered in Australian dollars (AUD).

Faecal calprotectin (FC) was measured by a quantitative enzyme immunoassay (fCALTM, Bühlmann, Schonenbuch, Switzerland) as per manufacturer’s instructions, without knowledge of patient data. Concentrations were expressed as μg/g of stool. FC measurement was performed at baseline (pre-operatively) and at 6, 12 and 18 mo post-operatively.

As costs were not normally distributed, medians and interquartile ranges of costs were calculated. A 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U Test was used to assess for statistically significant differences in costs between groups. Data were analysed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (Armonk NY: IBM Corp.).

Of the 174 patients (median age 38, 55% female) enrolled in the POCER study, 60 (median age 37, 60% female) were included in this analysis. Demographic and disease characteristics of the entire POCER cohort and the health-economic sub-cohort are shown in Table 2. Of the 60 patients, 43 (72%) were in the active care arm and 17 (28%) in the standard care arm. Average length of follow up for all patients was 17 mo, and was not different between standard and active care arms.

| Health economic sub-group | Entire POCER study cohort | P value | |

| n = 60 | n = 174 | ||

| n (male) | 24 (40) | 78 (45) | 0.516 |

| Age > 40 yr | 24 (40) | 68 (39) | 0.900 |

| Age, median | 37 | 36 | |

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| ≤ 16 yr | 4 (7) | 19 (11) | 0.340 |

| 17-40 yr | 49 (81) | 134 (77) | 0.451 |

| > 40 yr | 7 (12) | 21 (12) | 0.934 |

| Duration of Crohn's disease ≥ 10 yr | 29 (48) | 60 (34) | 0.154 |

| Disease location at surgery: | |||

| Ileum only (L1) | 33 (55) | 95 (55) | 0.957 |

| Colon only (L2) | 3 (5) | 11 (6) | 0.710 |

| Ileum and colon (L3) | 21 (35) | 68 (39) | 0.575 |

| Disease phenotype at surgery: | |||

| B1 (Inflammatory) | 5 (8) | 17 (10) | 0.742 |

| B2 (Stricture) | 18 (30) | 62 (36) | 0.428 |

| B3 (Penetrating) | 37 (62) | 95 (55) | 0.341 |

| Indication for surgery: | |||

| Failure of drug therapy | 12 (20) | 38 (22) | 0.764 |

| Obstruction | 14 (23) | 50 (29) | 0.418 |

| Perforation | 34 (57) | 86 (49) | 0.333 |

| Number of prior surgical resections | |||

| 0 | 47 (78) | 124 (71) | 0.287 |

| 1 | 9 (15) | 33 (19) | 0.490 |

| 2 | 1 (2) | 9 (5) | 0.247 |

| 3 or more | 3 (5) | 8 (5) | 0.899 |

| Active smoker | 22 (37) | 54 (31) | 0.422 |

| Immediate post-operative baseline drug therapy | |||

| Metronidazole alone | 9 (15) | 29 (17) | 0.763 |

| Thiopurine | 39 (65) | 101 (58) | 0.343 |

| Adalimumab | 12 (20) | 44 (25) | 0.408 |

| CDAI > 150 | 40 (67) | 113 (65) | 0.673 |

| CDAI > 200 | 30 (50) | 90 (52) | 0.465 |

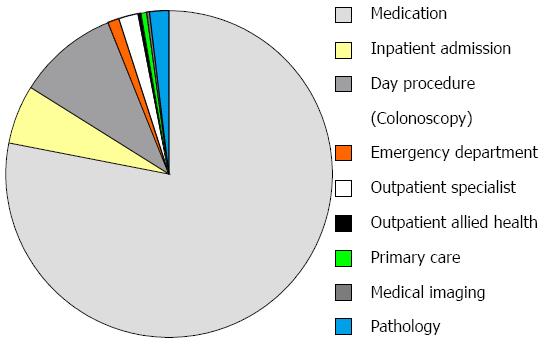

Median total healthcare cost per patient of post-operative care was AUD $6440 (IQR 2540-28069). Medications were the highest single cost driver, responsible for 78% of the total cost, of which adalimumab constituted 90%. Day procedures (colonoscopy) constituted 10% of the healthcare cost, followed by inpatient admissions, outpatient specialist consultations and pathology at 6%, 2% and 2%, respectively. Detailed cost breakdowns can be seen in Figure 2.

We have previously shown that by measuring FC post-operatively, the need for colonoscopy can be reduced by 47%. When used at 6 and 18 mo to select appropriate patients for colonoscopy, this would have reduced the cost of post-operative care by $1010 over 18 mo based on average colonoscopy costs from our cohort.

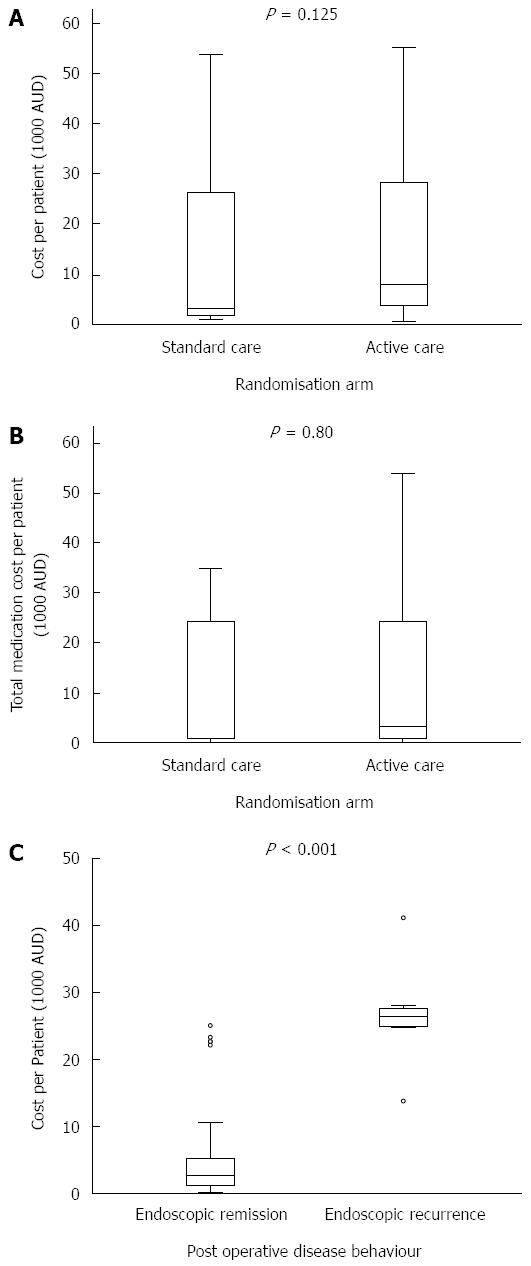

Median healthcare cost was non-statistically significantly higher in the active vs standard care arms [$8045 (IQR 3732-28288) vs $3221 (IQR 1693-26283), P = 0.125], Figure 3A.

Medications were the biggest cost items in both the active and standard care arms (both 78% of total), with adalimumab making up 90% of these costs in both arms. Median medication costs per patient were non-statistically significantly higher in those in the active vs standard care arm [$3286 (IQR 864-24421) vs $891 (IQR 868-24393), P = 0.80]. As colonoscopy at 6 mo was mandated for those in the active care arm, median day procedure (colonoscopy) costs were higher per patient in this group when compared to those in the standard care arm $1710 (IQR 574-2884) vs $694 (565-1591), P = 0.044.

Detailed costing breakdowns are shown in Figure 2.

Within the 43 active care patients, the median healthcare cost was higher in those who had endoscopic recurrence at 6 mo (n = 12) compared to those in remission (n = 31) [$26347 (IQR 25045-27485) vs $2729 (IQR 1182-5215), P < 0.001], Figure 3C. Most of this cost difference was accounted for by the increased need for medications among those with endoscopic recurrence [$24038 (IQR 24038-26710) vs $533 (IQR 200-3205), P < 0.001]. Medications contribute more to the total healthcare cost of patients with endoscopic recurrence compared to those in remission (95% vs 67%).

In the entire POCER study, treatment in the active care compared to standard care arms was associated with an 18% reduction in the risk of endoscopic recurrence (NNT 5.6)[17]. Hence on average, $861 was spent over 18 mo to prevent each endoscopic recurrence.

We have previously shown that routine FC testing for asymptomatic patients post-operatively, with colonoscopy reserved for those with a FC > 100 μg/g, could reduce the rate of post-operative colonoscopy by 47%[32]. When used at 6 and 18 mo to select patients for colonoscopy, measurement of FC would have reduced the cost of post-operative care by $1010 over 18 mo based on average colonoscopy costs from our cohort and the cost of FC testing.

This cost analysis of structured post-operative care after intestinal resection in Crohn’s disease has identified a number of findings. First, healthcare costs are substantial, with much of the cost relating to drug therapy. Secondly, active care involving endoscopic monitoring for disease recurrence, costs more than symptom-based monitoring. Thirdly, the occurrence of endoscopic recurrence increases costs significantly, related largely to drug therapy. Lastly, the use of FC to monitor for disease recurrence, a proven strategy, can substantially decrease post-operative costs.

The severity of endoscopic recurrence has been shown previously to predict the subsequent development of clinical recurrence and the need for surgery[14]. The costs inherent in this strategy of monitoring and treating-to-target to maintain mucosal healing are predicated on the assumption that in the longer term, disease recurrence, the development of disease complications, and the need for further surgery are reduced. Potential cost savings by way of a reduction in future surgery and a reduction in the subsequent development of short gut syndrome (a rare but catastrophic complication of repeated intestinal resections in Crohn’s disease) are significant. In the POCER cohort, the median cost of the inpatient admission for intestinal resection was $15662 (IQR 10364-17720), the annual cost of care per patients with short gut syndrome have been estimated as being between $100000 and $150000 per year[36]. However, longer term data are still needed to evaluate the cost of prolonged anti-TNF therapy and reduced interventions compared with less monitoring and drug therapy with a likely increased rate of intervention.

While recent trials have demonstrated the efficacy[16,18,37], and explored the cost-effectiveness[30,31], of some drug therapies in preventing post-operative Crohn’s disease recurrence, the cost of anti-TNF therapy and of an integrated package of care have not been evaluated. The healthcare costs of these resource-intensive strategies must be considered if these approaches are to be widely recommended.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe healthcare cost profiles in the management of post-operative Crohn’s disease. The post-operative period is completely different to treating known active disease outside of a surgical episode, the latter being clinically obvious and treatment essential. Post-operatively, patients are usually clinically well, as reflected in improved Crohn’s Disease Severity Index (CDAI) and quality of life scores[38]. For the patient and the treating physician, this changed focus from treating active disease to disease prevention requires its own health and cost-benefit analysis and justification.

The major limitation of this study is the small study size which included a sub-set of patients enrolled in the POCER study.

The POCER study demonstrated the efficacy of risk-tailored prophylactic drug therapy, early colonoscopy and treatment step-up in the event of endoscopic recurrence, for the prevention of post-operative recurrence[17]. The active care arm of the POCER study cost a median of $8045 per patient, with the cost of drug therapy exceeding the cost of colonoscopy, hospital admissions and specialist appointments. An alternative strategy involves the routine use of anti-TNF therapy for all patients at high-risk of recurrence, without inherent monitoring for recurrence and drug adjustment; the recent PREVENT study evaluated the efficacy of infliximab in this setting[39]. Such routine use of anti-TNF therapy would be more expensive in the short-term, but the longer term costs-benefits are unknown.

The significant proportion of healthcare costs attributable to adalimumab therapy in our study reflects recent studies that illustrate the change in cost profiles in inflammatory bowel disease management as a consequence of anti-TNF use. Anti-TNF drugs come at a considerable cost and have been found to increase the overall cost for patients with Crohn’s disease. Adalimumab is more cost-effective than infliximab because of the absence of incidental costs associated with the administration of infliximab including infusion centre admission and nursing care[40-42].

A recent cost-of-illness study by van der Valk et al[6] demonstrated that the cost of anti-TNF therapy for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease makes up the majority of health care cost, in excess of surgery and hospitalisation. Among Crohn’s disease patients in that study, medication costs accounted for 71% of total healthcare costs, of which 64% was related to anti-TNF therapy. Hospitalisation and surgery accounted for only 19% and less than 1%, respectively. In our study, similar to the study by van der Valk et al[6], outpatient specialist and general practitioner care accounted for small proportions of the total healthcare cost, at 3.7% and less than 1%, respectively. Australian data reflects similar trends in healthcare costs, with medications being the main cost driver in the care of patients with Crohn’s disease[43].

The introduction of biosimilar anti-TNF drugs, and a general trend towards lower drug pricing, may result in lower drug costs in the medium term[44]. Healthcare spending on biologics is predicted to fall between 10 and 50% in Europe and the United States following the introduction of biosimilar drugs[45-47]. Cost-effectiveness of the tested strategy may therefore change.

This study has identified the main costs associated with a proactive disease-prevention post-operative Crohn’s disease strategy. It provides the financial basis for current management and the planning of future strategies.

Maura McSweeney, Clinical Costing Analyst, Decisions Support Unit, St Vincent’s Public Hospital Melbourne. AbbVie, Gutsy Group, Gandel Philanthropy, Angior Foundation and Crohn’s Colitis Australia and The National Health and Medical Research Council provided research support.

Healthcare costs for Crohn’s disease are high. Active disease, surgery, hospitalisations and anti-TNF use are the key costs. Precent of 70 patients with Crohn’s disease require at least one surgical resection, and of these most develop disease recurrence. Post-operative strategies to prevent disease recurrence, which include endoscopic assessment and patient-tailored prophylactic drug therapy, are therefore desirable. However, the cost-effectiveness of such strategies is unknown.

Post-operative management for patients with Crohn’s disease has been an area of intense interest over recent years. Randomised studies have sought to define optimal drug therapy and monitoring algorithms. Anti-TNF drugs have consistently been found to be superior to other drugs in the prevention of recurrent Crohn’s disease. Anti-TNF drugs however come at a considerable expense to the health care system. This study is part of the Post-Operative Crohn’s Endoscopic Recurrence (POCER) platform of studies which has successfully defined the management of patients with Crohn’s disease following intestinal resection. Results from the POCER study have radically altered treatment algorithms and our understanding of drug therapy in the prevention of post-operative recurrence of Crohn’s disease. The POCER study has demonstrated that in patients at high risk of recurrence after “curative” surgery for Crohn’s disease, adalimumab (an anti-TNFα drug) prevents recurrent mucosal disease in most patients, and is superior to thiopurines. A strategy for the post-operative management of these patients has also been determined with treatment according to risk of recurrence, with 6 mo colonoscopy and treatment step-up for endoscopic recurrence, being significantly superior to optimal drug therapy alone, in preventing postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease. Selective potent immune suppression, adjusted if needed on the basis of colonoscopy, rather than its use in all high risk patients, was shown to lead to effective disease control in a majority of patients. The study described in this manuscript describes the health care costs involved in delivering this treatment and monitoring strategy compared to those required for the provision of standard post-operative care.

Post-operative strategies to prevent disease recurrence after intestinal resection are associated with high healthcare costs, the majority of which is medication driven. Endoscopic recurrence when compared to remission is associated with significantly higher healthcare costs. The POCER strategy, as illustrated in the active care arm of this study, is based on risk-related medication, monitoring for early disease recurrence, and treatment intensification when needed. It is associated with a reduction in post-operative endoscopic recurrence without a significantly greater cost than standard care.

Strategies that prevent endoscopic recurrence may therefore be associated with substantial healthcare savings downstream, making the POCER algorithm a potentially cost effective strategy. Further, using FC to select patients appropriate for colonoscopy reduces costs significantly.

This manuscript by Wright et al is the first study to describe healthcare cost profiles in the management of post-operative Crohn’s disease. The manuscript is well written, it is certainly interesting for the readers of the journal, and I believe that could be accepted for publication.

P- Reviewer: Caboclo JLF, Rocha R, Trifan A S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Feagan BG, Vreeland MG, Larson LR, Bala MV. Annual cost of care for Crohn’s disease: a payor perspective. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1955-1960. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 146] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Longobardi T, Bernstein CN. Health care resource utilization in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:731-743. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cohen RD, Larson LR, Roth JM, Becker RV, Mummert LL. The cost of hospitalization in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:524-530. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 119] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Silverstein MD, Loftus EV, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Feagan BG, Nietert PJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Clinical course and costs of care for Crohn’s disease: Markov model analysis of a population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:49-57. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 273] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bassi A, Dodd S, Williamson P, Bodger K. Cost of illness of inflammatory bowel disease in the UK: a single centre retrospective study. Gut. 2004;53:1471-1478. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 237] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van der Valk ME, Mangen MJ, Leenders M, Dijkstra G, van Bodegraven AA, Fidder HH, de Jong DJ, Pierik M, van der Woude CJ, Romberg-Camps MJ. Healthcare costs of inflammatory bowel disease have shifted from hospitalisation and surgery towards anti-TNFα therapy: results from the COIN study. Gut. 2014;63:72-79. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 390] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Odes S, Vardi H, Friger M, Wolters F, Hoie O, Moum B, Bernklev T, Yona H, Russel M, Munkholm P. Effect of phenotype on health care costs in Crohn’s disease: A European study using the Montreal classification. J Crohns Colitis. 2007;1:87-96. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Risk factors for surgery and postoperative recurrence in Crohn’s disease. Ann Surg. 2000;231:38-45. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 443] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Binder V, Hendriksen C, Kreiner S. Prognosis in Crohn’s disease--based on results from a regional patient group from the county of Copenhagen. Gut. 1985;26:146-150. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 229] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cosnes J, Nion-Larmurier I, Beaugerie L, Afchain P, Tiret E, Gendre JP. Impact of the increasing use of immunosuppressants in Crohn’s disease on the need for intestinal surgery. Gut. 2005;54:237-241. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 479] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Harmsen WS, Tremaine WJ, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ, Loftus EV. Surgery in a population-based cohort of Crohn’s disease from Olmsted County, Minnesota (1970-2004). Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1693-1701. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 214] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Olaison G, Smedh K, Sjödahl R. Natural course of Crohn’s disease after ileocolic resection: endoscopically visualised ileal ulcers preceding symptoms. Gut. 1992;33:331-335. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 346] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Kerremans R, Coenegrachts JL, Coremans G. Natural history of recurrent Crohn’s disease at the ileocolonic anastomosis after curative surgery. Gut. 1984;25:665-672. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 572] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 535] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Beyls J, Kerremans R, Hiele M. Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:956-963. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Landsend E, Johnson E, Johannessen HO, Carlsen E. Long-term outcome after intestinal resection for Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1204-1208. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Regueiro M, Schraut W, Baidoo L, Kip KE, Sepulveda AR, Pesci M, Harrison J, Plevy SE. Infliximab prevents Crohn’s disease recurrence after ileal resection. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:441-450.e1; quiz 716. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 443] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 412] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | De Cruz P, Kamm MA, Hamilton AL, Ritchie KJ, Krejany EO, Gorelik A, Liew D, Prideaux L, Lawrance IC, Andrews JM. Crohn’s disease management after intestinal resection: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1406-1417. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 385] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Regueiro M, Kip KE, Baidoo L, Swoger JM, Schraut W. Postoperative therapy with infliximab prevents long-term Crohn’s disease recurrence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1494-502.e1. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Doherty G, Bennett G, Patil S, Cheifetz A, Moss AC. Interventions for prevention of post-operative recurrence of Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD006873. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 95] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Priest VL, Begg EJ, Gardiner SJ, Frampton CM, Gearry RB, Barclay ML, Clark DW, Hansen P. Pharmacoeconomic analyses of azathioprine, methotrexate and prospective pharmacogenetic testing for the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24:767-781. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dubinsky MC, Reyes E, Ofman J, Chiou CF, Wade S, Sandborn WJ. A cost-effectiveness analysis of alternative disease management strategies in patients with Crohn’s disease treated with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2239-2247. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 130] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA, Podolsky DK, Sands BE, Braakman T, DeWoody KL. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398-1405. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1969] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1777] [Article Influence: 71.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh D, Panaccione R, Wolf D, Pollack P. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:323-333; quiz 591. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1153] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1126] [Article Influence: 62.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Feagan BG, Panaccione R, Sandborn WJ, D’Haens GR, Schreiber S, Rutgeerts PJ, Loftus EV, Lomax KG, Yu AP, Wu EQ. Effects of adalimumab therapy on incidence of hospitalization and surgery in Crohn’s disease: results from the CHARM study. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1493-1499. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 277] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bodger K, Kikuchi T, Hughes D. Cost-effectiveness of biological therapy for Crohn’s disease: Markov cohort analyses incorporating United Kingdom patient-level cost data. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:265-274. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Loftus EV, Johnson SJ, Yu AP, Wu EQ, Chao J, Mulani PM. Cost-effectiveness of adalimumab for the maintenance of remission in patients with Crohn’s disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1302-1309. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lindsay J, Punekar YS, Morris J, Chung-Faye G. Health-economic analysis: cost-effectiveness of scheduled maintenance treatment with infliximab for Crohn’s disease--modelling outcomes in active luminal and fistulizing disease in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:76-87. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jaisson-Hot I, Flourié B, Descos L, Colin C. Management for severe Crohn’s disease: a lifetime cost-utility analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20:274-279. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Dretzke J, Edlin R, Round J, Connock M, Hulme C, Czeczot J, Fry-Smith A, McCabe C, Meads C. A systematic review and economic evaluation of the use of tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors, adalimumab and infliximab, for Crohn’s disease. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15:1-244. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ananthakrishnan AN, Hur C, Juillerat P, Korzenik JR. Strategies for the prevention of postoperative recurrence in Crohn’s disease: results of a decision analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:2009-2017. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Doherty GA, Miksad RA, Cheifetz AS, Moss AC. Comparative cost-effectiveness of strategies to prevent postoperative clinical recurrence of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1608-1616. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wright EK, Kamm MA, De Cruz P, Hamilton AL, Ritchie KJ, Krejany EO, Leach S, Gorelik A, Liew D, Prideaux L. Measurement of fecal calprotectin improves monitoring and detection of recurrence of Crohn’s disease after surgery. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:938-947.e1. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Dowsey MM, Liew D, Choong PF. Economic burden of obesity in primary total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:1375-1381. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | MBS Online. Medicare Benefits Schedule 2013. Available from: http://www.mbsonline.gov.au. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme 2015. Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Schalamon J, Mayr JM, Höllwarth ME. Mortality and economics in short bowel syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:931-942. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 106] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Rutgeerts P, Hiele M, Geboes K, Peeters M, Penninckx F, Aerts R, Kerremans R. Controlled trial of metronidazole treatment for prevention of Crohn’s recurrence after ileal resection. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1617-1621. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Wright EK, Kamm MA, De Cruz P, Hamilton AL, Ritchie KJ, Krejany EO, Gorelik A, Liew D, Prideaux L, Lawrance IC. Effect of intestinal resection on quality of life in Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:452-462. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Regueiro M, Feagan BG, Zou B, Johanns J, Blank M, Chevrier M, Plevy SE, Popp J, Cornillie F, Lukas M. Infliximab for prevention of recurrence of post-surgical Crohn’s disease following ileocolonic resection: A randomized placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:S-141. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Saro C, da la Coba C, Casado MA, Morales JM, Otero B. Resource use in patients with Crohn’s disease treated with infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1313-1323. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Rudakova AV. [Cost-effectiveness of tumor necrosis factor in Crohn’s disease]. Eksp Klin Gastroenterol. 2012;83-86. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Yu AP, Johnson S, Wang ST, Atanasov P, Tang J, Wu E, Chao J, Mulani PM. Cost utility of adalimumab versus infliximab maintenance therapies in the United States for moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27:609-621. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Niewiadomski O, Studd C, Hair C, Wilson J, McNeill J, Knight R, Prewett E, Dabkowski P, Dowling D, Alexander S. Health Care Cost Analysis in a Population-based Inception Cohort of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients in the First Year of Diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:988-996. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Danese S, Gomollon F. ECCO position statement: the use of biosimilar medicines in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:586-589. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 145] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Haustein R, de Millas C, Hoer A, Haussler B. Saving money in the European healthcare systems with biosimilars. GaBI J. 2012;1:120-126. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Shapiro RJ, Singh K, Mukim M. The potential American market for generic biological treatments and the associated cost savings. 2008; Available from: http://www.sonecon.com/docs/studies/0208_GenericBiologicsStudy.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 47. | Mulcahy AW, Predmore Z, Mattke S. The cost savings potential of biosimilar drugs in the United States, 2014. Available from: http://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE127.html. [Cited in This Article: ] |