Published online Dec 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i48.13566

Peer-review started: July 4, 2015

First decision: July 19, 2015

Revised: August 6, 2015

Accepted: September 14, 2015

Article in press: September 15, 2015

Published online: December 28, 2015

AIM: To evaluate the correlation between fecal calprotectin (fC), C-reactive protein (CRP), and endoscopic disease score in Asian inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients.

METHODS: Stool samples were collected and assessed for calprotectin levels by Quantum Blue Calprotectin High Range Rapid test. Crohn’s disease endoscopic index of severity (CDEIS) and ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS) were used for endoscopic lesion scoring.

RESULTS: A total of 88 IBD patients [36 patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) and 52 with ulcerative colitis (UC)] were enrolled. For CD patients, fC correlated with CDEIS (r = 0.465, P = 0.005) and CRP (r = 0.528, P = 0.001). fC levels in UC patients correlated with UCEIS (r = 0.696, P < 0.0001) and CRP (r = 0.529, P = 0.0005). Calprotectin could predict endoscopic remission (CDEIS < 6) with 50% sensitivity and 100% specificity (AUC: 0.74) in CD patients when using 918 μg/g as the cut-off. When using 191 μg/g as the cut-off in UC patients, calprotectin could be used for predicting endoscopic remission (UCEIS < 3) with 88% sensitivity and 75% specificity (AUC: 0.87).

CONCLUSION: fC correlated with both CDEIS and UCEIS. fC could be used as a predictor of endoscopic remission for Asian IBD patients.

Core tip: Mucosal healing is the goal in treating inflammatory bowel disease patients, and endoscopic examination remains the gold standard for evaluating mucosal status. Our results provide more evidence that fecal calprotectin (fC) correlates well with mucosal disease activity by using endoscopic disease score of ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS) and Crohn's disease endoscopic index of severity (CDEIS). The correlation of fC was higher in UCEIS than in CDEIS. fC could be used as a predictor of endoscopic remission for Asian inflammatory bowel disease patients.

- Citation: Lin WC, Wong JM, Tung CC, Lin CP, Chou JW, Wang HY, Shieh MJ, Chang CH, Liu HH, Wei SC, Taiwan Society of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Multicenter Study. Fecal calprotectin correlated with endoscopic remission for Asian inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(48): 13566-13573

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i48/13566.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i48.13566

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory and destructive disease of the gastrointestinal tract. The chronic active inflammation causes ulcerations, stricture formations, and perforations and is a risk factor for the development of dysplasia and cancer[1]. To reduce longstanding IBD complications, the treatment goal in IBD patients is mucosal healing.

Certain classifications have been constructed to monitor the clinical parameters and treatment effects in IBD patients, such as the Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) and the Montreal classification[2,3]. However, these scoring systems may be unreliable, because patients give subjective assessments of their symptoms, and clinicians are subjective in their assessments of patients. The gold standard for monitoring patients with IBD remains endoscopy, which is a time-consuming, expensive, and invasive procedure. In addition, the bowel cleansing that patients must undergo before endoscopic procedures is uncomfortable and inconvenient.

A stool sample analysis is noninvasive without the necessity of bowel preparation, relatively convenient, and much less time-consuming for the patient. Calprotectin, a calcium-binding protein, originates from neutrophils found in both plasma and stool[4]. It is markedly elevated in inflammatory processes, such as IBD, sepsis, and necrotizing enterocolitis[5]. There are many bacterial proteases in feces, however, calprotectin is resistant to these enzymes, and, therefore, it is possible to measure it in a fecal sample[6]. In addition, samples can be stored for several days and shipped at ambient temperatures. Thus, measurement of this biomarker provides a reliable method for the degree of inflammation in the bowel[7]. Recently, fecal calprotectin (fC) levels have been reported to be a predictive marker of mucosal healing in patients with IBD[5]. Its levels have been correlated with histological disease activity and could be used as a relapse marker and a disease activity marker for IBD patients[6,8,9].

There are two types of fC tests, including fully quantitative laboratory-based technologies [enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) platform], fully quantitative rapid tests, and semi-quantitative point-of-care tests [10]. The level of calprotectin is age-related. Two to 9 year-old children and adults above the age of 60 have significantly higher concentrations of calprotectin than 10 to 59 year-olds[11]. Furthermore, its level is higher in infants in rural areas than urban areas[12]. There are limited data regarding calprotectin levels in different races. Reports from Western countries show that fC levels significantly correlate with endoscopic disease activity in IBD[13]. In Japan, its levels were found to be correlated with endoscopic disease activity in pediatric and post-operative Crohn's disease (CD) patients[14,15]. For ulcerative colitis (UC), fC correlated with clinical activity in China[16]. We were unable to find any report about evaluating fC, C-reactive protein (CRP), and endoscopic index in either Asian UC or CD patients. In order to define whether the fC could be used as a surrogate marker for mucosal healing, or even as a predictor for endoscopic remission, we examined the correlation between fC, CRP, and the endoscopic disease index in Asian IBD patients.

All patients signed the informed written consent for participation in this study, which was approved by the institution’s Ethics Committee. This was a prospective, multi-center study under the collaboration of the Taiwan Society of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The inclusion criteria were: patients who were between 16 and 80 years of age; patients who were diagnosed with IBD based on standard endoscopic, radiological, and histological criteria; and outpatients who regularly followed up but not newly diagnosed, without acute illness under active medication adjustment. Exclusion criteria were: patients with possible concurrent gastrointestinal infection (fever and diarrhea) or malignancies, pregnant females, and patients who abused alcohol or regularly consumed aspirin, antibiotics, cytotoxic drugs, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (more than two tablets per week). In Taiwan, when the patient’s condition is stationary, the regular follow-up interval for the outpatient is 3 mo. Therefore, we invited those patients who were going to have their follow-up endoscope before their next visit to enroll in this study. In order to minimize inconvenience for patients, we educated the patients on how to collect stool samples and had them return the samples prior to or on the next visit. All invited patients who accepted these terms were included during the study period. In this way, the interval between calprotectin and CRP measurements and the endoscopic examination was within 3 mo. Serum CRP level was obtained from the clinical records (normal level was less than 0.8 mg/dL in all centers involved in this study).

All UC patients underwent complete colonoscopy, and all CD patients underwent ileocolonoscopy. CD endoscopic index of severity (CDEIS)[17] and UC endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS)[18] were used for the endoscopic lesions scoring. The CDEIS is based on the recognition of elementary lesions (non-ulcerated lesions, superficial and deep ulcerations) associated with the appreciation of their surface in five different segments (ileum, right colon, transverse, left colon, and rectum)[17]. The CDEIS ranges from 0 (normal) to 44 (most severe). The UCEIS is based on vascular patterns (2 levels), bleeding (3 levels), and erosions and ulcers (3 levels)[18]. The final score represents the sum of the components, with the UCEIS ranging from 0 (normal) to 8 (most severe). Endoscopic findings were recorded on color imaging and graded according to CDEIS and UCEIS by two specialist physicians who were blinded to the patient’s clinical details.

Fecal samples (around 90 mg) were collected from all of the patients. Patients were instructed to collect the sample at home and have them stored in a refrigerator. Samples were delivered on the next day and transferred to the study laboratory for analysis. The laboratory personnel carrying out the analysis were blinded to the clinical history, data, and the endoscopic findings of the patients. The values quoted as normal in our laboratory were 100 μg/g. fC levels were assessed by using a commercially-available ELISA, Quantum Blue Calprotectin High Range Rapid Test (Buhlmann laboratories AG, Schonenbuch, Switzerland).

Each value is presented as a median with the interquartile range (IQR). For data analyses we used SPSS for Windows software 14.0 (Chicago, IL, United States). For correlation analyses, we used the nonparametric Spearman’s rank order correlation (r). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for exploring changes between related variables. Sensitivity and specificity were estimated by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The calprotectin cut-off values were selected by the Youden’s index using ROC curves. The areas under the ROC curve (AUCs) were calculated for fC, and the combination of fC and CRP, respectively. All statistical testing was two-sided, and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

A total of 88 patients, 52 diagnosed with UC and 36 diagnosed with CD, were included in this study. The clinical characteristics of the 88 enrolled patients are listed in Table 1. The interval between the fC measurement and the endoscopy ranged from 4 to 80 d, with a mean of 36.5 d.

| UC (n = 52) | CD (n = 36) | |

| Gender (M/F) | 34/18 | 19/17 |

| Age (yr) | 44 (17-76) | 34 (21-71) |

| Disease extent/location | ||

| E1/L1 | 13 (25) | 4 (11) |

| E2/L2 | 15 (29) | 8 (22) |

| E3/L3 | 24 (46) | 24 (67) |

| EIS [median (IQR)] | 3 (1-4) | 8 (5.2-21) |

| Calprotectin (μg/g) [median (IQR)] | 447 (116-1700) | 309 (100-1130) |

| CRP [median (IQR)] | 0.17 (0.04-0.51) | 0.15 (0.05-0.91) |

The UC patients were predominantly male (65%), with an age range of 17 to 76 years (median age of 44). The correlation between readers for UCEIS was good, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.8980. They had a median (IQR) UCEIS of 3 (1-4), a median (IQR) CRP level of 0.17 (0.04-0.51) mg/L, and a median (IQR) fC level of 447 (116-1700) μg/g. When separated by disease extent, as shown in Table 2, the median level of fC in UC was 116 μg/g in proctitis, 478 μg/g in left-sided UC, and 611 μg/g in extensive UC. The fC level in UC patients was not statistically different between age groups more or less than 60 years old (mean ± SD: 331 ± 638 and 1033 ± 2038, respectively; P = 0.37). The median level of CRP in UC was 0.06 mg/dL in proctitis, 0.19 mg/dL in left-sided UC, and 0.30 mg/dL in extensive UC. The median (IQR) UCEIS was 3 (1-4) in proctitis, 3 (1-4) in left-sided UC, and 3.5 (3-4.5) in extensive UC. For each biomarker of calprotectin, there was no significant difference among proctitis, left-sided UC, and extensive UC patients.

| Fecal calprotectin (μg/g) | UCEIS | CRP | ||||

| Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | |

| E1 | 116 | 100-620 | 3 | 1-4 | 0.06 | 0.04-0.17 |

| E2 | 478 | 214.5-1249 | 3 | 1-4 | 0.19 | 0.04-0.45 |

| E3 | 611 | 172-1800 | 3.5 | 3-4.5 | 0.3 | 0.05-1.04 |

Of the 36 CD patients enrolled, there were slightly more males than females (52% male), and the age ranged from 21 to 71 years, with a median age of 34. The correlation between readers for CDEIS was also good, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.9632. They had a median (IQR) CDEIS of 8.0 (5.2-21), a median (IQR) CRP level of 0.15 (0.05-0.91) mg/L, and a median (IQR) fC level of 309 (100-1130) μg/g. The fC level in CD patients was not statistically different between patient groups more or less than 60 years old (mean ± SD: 3250 ± 35436 and 1369 ± 2257, respectively; P = 0.115). When separated by disease location, as shown in Table 3, the median (IQR) level of fC in CD was 2693 (1071-5010) μg/g in ileum (L1), 176 (100-573) μg/g in colon (L2), and 279 (100-2175) μg/g in ileocolon (L3) subtypes. The median (IQR) level of CRP in CD was 0.56 (0.13-1.09) mg/dL in L1, 0.05 (0.03-0.15) mg/dL in L2, and 0.17 (0.08-1.27) mg/dL in L3 subtypes. The median (IQR) CDEIS was 9 (8-19) in L1, 3.9 (3.2-9.2) in L2, and 8 (6-28) in L3 subtypes. For each biomarker of calprotectin, there was no significant difference among the L1, L2, and L3 patients.

| Fecal calprotectin (μg/g) | CDEIS | CRP | ||||

| Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | |

| L1 | 2693 | 1071-5010 | 9 | 8-18.5 | 0.56 | 0.13-1.09 |

| L2 | 176 | 100-573 | 3.9 | 3.2-9.2 | 0.05 | 0.03-0.15 |

| L3 | 279 | 100-2175 | 8 | 6-27.5 | 0.17 | 0.08-1.27 |

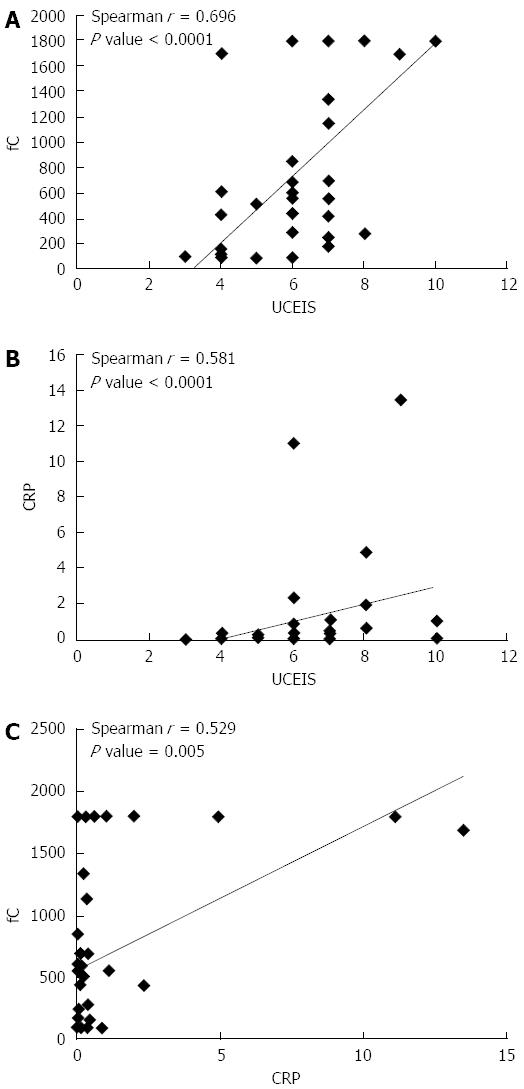

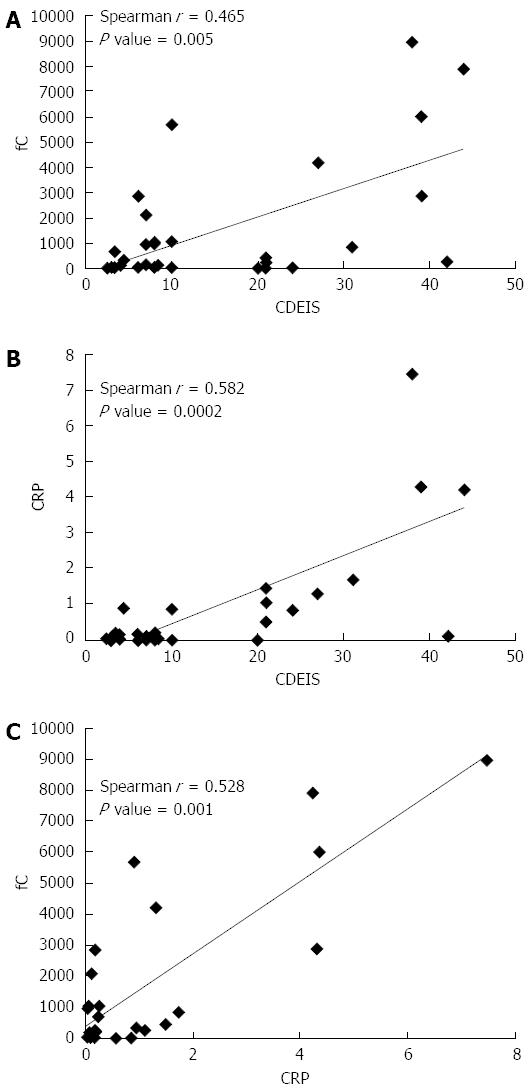

In UC patients, UCEIS correlated significantly with fC level, with a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.696 (P < 0.0001) (Figure 1A). UCEIS also correlated with the levels of CRP (Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.581, P < 0.0001) (Figure 1B). fC correlated with CRP, with a correlation coefficient of 0.529 (P = 0.005) (Figure 1C). Although there was a trend suggesting that fC increased from E1 (proctitis) to E3 (total colitis), there was no correlation between the extent of disease and fC, CRP, and UCEIS. In the CD patients, CDEIS correlated with fC (Figure 2A) as well as with CRP (Figure 2B), with Spearman correlation coefficients of 0.465 (P = 0.005) and 0.582 (P = 0.0002) for calprotectin and CRP, respectively. Moreover, the correlation coefficient was 0.528 (P = 0.001) for CRP and fC (Figure 2C). There was no correlation between the location of disease and fC (P = 0.060), CRP (P = 0.153) and CDEIS (P = 0.081).

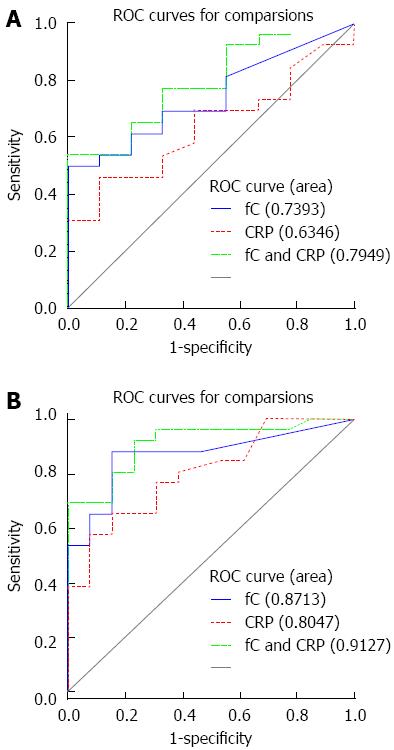

In CD, where the threshold for endoscopic remission has been set by a systemic review study as a CDEIS < 6[19], the best discriminative cutoff was obtained at a calprotectin threshold of 918 μg/g, which could predict endoscopic remission with 50% sensitivity and 100% specificity (AUC of 0.74). In the UC group, where the threshold for endoscopic remission was set as a UCEIS < 3, the ROC curve analysis (AUC of 0.87) revealed a cut-off calprotectin level of 191 μg/g, which could predict mucosa healing with a sensitivity and specificity of 88% and 75%, respectively. As shown in Figure 3, when using the combination of CRP and fC, the predicting ability of endoscopic remission increased, but it did not significantly increase when compared with fC alone (P value for CD: 0.07 and for UC: 0.28).

When we divided the results by mean interval (36 d) of fC measurement and endoscopy, the Spearman correlation coefficient of fC and UCEIS was 0.810 (P = 0.008) for those with the shorter interval (< 36 d), and the correlation coefficient of fC and UCEIS decreased to 0.388 (P = 0.342) for those with the longer interval (> 36 d). However, there was no such difference for the CD patients. The Spearman correlation coefficient of fC and CDEIS was 0.509 for the shorter interval (< 36 d ) (P = 0.0631), and the correlation coefficient of fC and CDEIS was 0.511 (P = 0.0179) for the longer interval (> 36 d) group.

The fC test is a simple, non-invasive, and reproducible test. To date, there have been few studies on the relationship between fC and endoscopic indices (mucosal status) in the Asian population. In this study, we assessed the association between fC, CRP level, and endoscopic disease activity. Our results demonstrated that the concentration of fC in Asian IBD patients was significantly correlated with the endoscopic index, which was evaluated by the UCEIS for UC and CDEIS for CD patients.

In our study, a calprotectin level below 191 μg/g was associated with mucosal healing in UC (UCEIS < 3), whereas a calprotectin level below 918 μg/g in CD reflected endoscopic remission (CDEIS < 6). This result is consistent with a Denmark study[20] that showed the cutoff level of fC was 192 μg/g for predicting endoscopic mucosa healing in UC, as assesed using both the UCEIS and Mayo Endoscopic Score. This finding confirmed that fC reflects endoscopic disease activity with different endoscopic scores. Another European report[13] observed that an fC level below 250 μg/g was predictive for endoscopic remission (CDEIS ≤ 3) in CD patients. In UC, an fC level above 250 μg/g indicated active mucosal disease activity (Mayo Endoscopic Score > 0). Here, we provide additional necessary evidence that fC levels correlate significantly with endoscopic disease activity in Asian IBD patients.

There is evidence that fC levels correlate more closely with histological evaluation than macroscopic findings, suggesting that this biological marker is more sensible than endoscopy in evaluating IBDs activity[9,20,21]. In combination with our results, the fC levels could help us identify not only endoscopic but also histologic healing. Therefore, fC could be used as a surrogate marker for mucosal status in both CD and UC patients. Although it has been reported that fC tended to be higher in patients more than 60 years old[11], we found no statistically significant difference between patients more or less than 60 years old for both UC and CD.

In clinical practice, these cut-off points could be used to guide treatment decisions, where patients with calprotectin levels higher than these cut-off points will need treatment intensification or escalation. We found different studies reporting various cut-off levels of fC with endoscopic disease activity, which might be due to differences in patient selection, the extent of disease, and the remission duration[22]. Based on these studies, the use of serial fC measurements to detect endoscopic recurrence could potentially overcome the imperfect sensitivity of individual measurements and was better than using a cut-off level of fC[23]. Although the combination of fC and CRP increased the predictive ability, it did not reach statistical significance, which may be due to an underpowered sample.

In previous studies[24-31], the correlation coefficients ranged from 0.48-0.83 for fC with endoscopic disease activity and from 0.46-0.61 for CRP in CD patients. In UC, the correlation coefficient ranged from 0.51-0.83 for fC with endoscopic disease activity. In our study, we found that the correlation between fC concentration and endoscopic disease activity was higher in patients with UC. We also found that the fC can rapidly reflect the mucosal condition, as demonstrated by the stronger correlations when the intervals between fC measurement and endoscopy were shorter. Costa and colleagues reported a study describing that a high concentration of fC was associated with a 14-fold relapse risk in patients with UC and a 2-fold relapse risk in patients with CD, indicating that a high concentration of fC may be a more accurate predictive marker of relapse in UC than in CD[32]. In contrast to UC, patients with CD have stronger CRP responses[33]. This finding may be related to the fact that transmural inflammation is seen in patients with CD, whereas the inflammation in UC patients is confined to the mucosa. Therefore, fC levels seem to represent a stronger biomarker for monitoring endoscopic activity in UC patients. For patients with CD, increased levels of both CRP and fC are likely to be sufficient to identify an active mucosal disease.

As for the disease extent in IBD, ileocolonic and colonic CD significantly correlated with positive calprotectin tests and the probability of relapse[22,33]. It was reported that patients with ileal CD had significantly lower fC levels than those with ileocolonic disease, even in the presence of large ulcers[34]. In UC patients, a previous study showed that the fC increased significantly with disease extent in proctitis and left-sided colitis but the difference was not statistically significant[20]. In our study, we did not find a correlation between disease location and fC in UC or CD patients. However, fC, CRP levels, and CDEIS were higher in patients with ileum involvement than in CD patient with other sites affected. In UC, the extensive type had higher fC, CRP levels, and UCEIS but without statistical significance.

In conclusion, fC correlated with both the CDEIS for CD patients and the UCEIS for UC patients. Our results provide additional evidence that fC correlates well with mucosal disease activity. Therefore, fC levels could be used as a surrogate marker for monitoring mucosal status as well as predicting endoscopic remission of not only European but also the Asian IBD patients.

The authors would like to acknowledge statistical assistance provided by the Taiwan Clinical Trial Bioinformatics and Statistical Center, Training Center, and Pharmacogenomics Laboratory. We thank the second Core Laboratory of the Department of Medical Research of the National Taiwan University Hospital for technical assistance.

Mucosal healing is the goal in treating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients, and endoscopic examination remains the gold standard for evaluating the mucosal status. Recently, fecal calprotectin (fC) levels have been reported to be a predictive marker of mucosal healing in IBD. The aim of this study was to evaluate the correlation between fC, C-reactive protein, and endoscopic disease score.

Previously, several studies have reported that fC is a stronger predictive marker of relapse in ulcerative colitis (UC) than in Crohn’s disease (CD) with colon involvement but not ileal CD. However, the effect of fC is less known in Asian patients. Therefore, we performed this head-to-head comparison for CD and UC.

Those results demonstrated that the concentration of fC in Asian IBD patients was significantly correlated to the endoscopic index that was evaluated by the UC endoscopic index of severity for UC and CD endoscopic index of severity for CD patients. In agreement with the previous studies, when comparing fC level with endoscopic activity index in CD and UC, the correlation was higher in UC than in CD.

fC is an extremely stable protein, and it can be found unaltered in stool for longer than 7 d. Thus, measurement of this biomarker provides a reliable method for determining the degree of inflammation in the bowel.

The study is certainly interesting and well designed. It sheds some light on the important issue of non-invasive evaluation of treatment effect in IBD patients.

P- Reviewer: Jadallah KA, Yuksel I S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Rutter M, Saunders B, Wilkinson K, Rumbles S, Schofield G, Kamm M, Williams C, Price A, Talbot I, Forbes A. Severity of inflammation is a risk factor for colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:451-459. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 895] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 824] [Article Influence: 41.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Best WR. Predicting the Crohn’s disease activity index from the Harvey-Bradshaw Index. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:304-310. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 194] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749-753. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1970] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2080] [Article Influence: 115.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Andersson KB, Sletten K, Berntzen HB, Dale I, Brandtzaeg P, Jellum E, Fagerhol MK. The leucocyte L1 protein: identity with the cystic fibrosis antigen and the calcium-binding MRP-8 and MRP-14 macrophage components. Scand J Immunol. 1988;28:241-245. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 78] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bosco Dhas DB, Bhat BV, Gane DB. Role of Calprotectin in Infection and Inflammation. Curr Pediatr Res. 2012;16:83-94. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Paduchova Z, Durackova Z. Fecal calprotectin as a promising marker of inflammatory diseases. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2009;110:598-602. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Røseth AG, Fagerhol MK, Aadland E, Schjønsby H. Assessment of the neutrophil dominating protein calprotectin in feces. A methodologic study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:793-798. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 468] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Bridger S, Fagerhol MK, Bjarnason I. Surrogate markers of intestinal inflammation are predictive of relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:15-22. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 545] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 523] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Bunn SK, Bisset WM, Main MJ, Gray ES, Olson S, Golden BE. Fecal calprotectin: validation as a noninvasive measure of bowel inflammation in childhood inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33:14-22. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 166] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg11/resources/guidance-faecal-calprotectin-diagnostic-tests-for-inflammatory-diseases-of-the-bowel-pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Joshi S, Lewis SJ, Creanor S, Ayling RM. Age-related faecal calprotectin, lactoferrin and tumour M2-PK concentrations in healthy volunteers. Ann Clin Biochem. 2010;47:259-263. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liu JR, Sheng XY, Hu YQ, Yu XG, Westcott JE, Miller LV, Krebs NF, Hambidge KM. Fecal calprotectin levels are higher in rural than in urban Chinese infants and negatively associated with growth. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:129. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | D’Haens G, Ferrante M, Vermeire S, Baert F, Noman M, Moortgat L, Geens P, Iwens D, Aerden I, Van Assche G. Fecal calprotectin is a surrogate marker for endoscopic lesions in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2218-2224. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 553] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 577] [Article Influence: 48.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aomatsu T, Yoden A, Matsumoto K, Kimura E, Inoue K, Andoh A, Tamai H. Fecal calprotectin is a useful marker for disease activity in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2372-2377. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yamamoto T, Shiraki M, Bamba T, Umegae S, Matsumoto K. Faecal calprotectin and lactoferrin as markers for monitoring disease activity and predicting clinical recurrence in patients with Crohn’s disease after ileocolonic resection: A prospective pilot study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2013;1:368-374. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xiang JY, Ouyang Q, Li GD, Xiao NP. Clinical value of fecal calprotectin in determining disease activity of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:53-57. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mary JY, Modigliani R. Development and validation of an endoscopic index of the severity for Crohn’s disease: a prospective multicentre study. Groupe d’Etudes Thérapeutiques des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif (GETAID). Gut. 1989;30:983-989. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 634] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 613] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Travis SP, Schnell D, Krzeski P, Abreu MT, Altman DG, Colombel JF, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lémann M, Lichtenstein GR. Developing an instrument to assess the endoscopic severity of ulcerative colitis: the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS). Gut. 2012;61:535-542. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 376] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Neurath MF, Travis SP. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gut. 2012;61:1619-1635. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 531] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 577] [Article Influence: 48.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Theede K, Holck S, Ibsen P, Ladelund S, Nordgaard-Lassen I, Nielsen AM. Level of Fecal Calprotectin Correlates With Endoscopic and Histologic Inflammation and Identifies Patients With Mucosal Healing in Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1929-1936.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 104] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Limburg PJ, Ahlquist DA, Sandborn WJ, Mahoney DW, Devens ME, Harrington JJ, Zinsmeister AR. Fecal calprotectin levels predict colorectal inflammation among patients with chronic diarrhea referred for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2831-2837. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gallo A, Gasbarrini A, Passaro G, Landolfi R, Montalto M. Role of fecal calprotectin in monitoring response to therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Cell Immunol. 2014;5:252. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schoepfer AM, Lewis JD. Serial fecal calprotectin measurements to detect endoscopic recurrence in postoperative Crohn’s disease: is colonoscopic surveillance no longer needed? Gastroenterology. 2015;148:889-892. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Holmquist L, Ahrén C, Fällström SP. Clinical disease activity and inflammatory activity in the rectum in relation to mucosal inflammation assessed by colonoscopy. A study of children and adolescents with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990;79:527-534. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schoepfer AM, Beglinger C, Straumann A, Trummler M, Renzulli P, Seibold F. Ulcerative colitis: correlation of the Rachmilewitz endoscopic activity index with fecal calprotectin, clinical activity, C-reactive protein, and blood leukocytes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1851-1858. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 234] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Schoepfer AM, Beglinger C, Straumann A, Trummler M, Vavricka SR, Bruegger LE, Seibold F. Fecal calprotectin correlates more closely with the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease (SES-CD) than CRP, blood leukocytes, and the CDAI. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:162-169. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 388] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | D’Incà R, Dal Pont E, Di Leo V, Ferronato A, Fries W, Vettorato MG, Martines D, Sturniolo GC. Calprotectin and lactoferrin in the assessment of intestinal inflammation and organic disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:429-437. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 157] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hanai H, Takeuchi K, Iida T, Kashiwagi N, Saniabadi AR, Matsushita I, Sato Y, Kasuga N, Nakamura T. Relationship between fecal calprotectin, intestinal inflammation, and peripheral blood neutrophils in patients with active ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1438-1443. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 86] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sipponen T, Savilahti E, Kärkkäinen P, Kolho KL, Nuutinen H, Turunen U, Färkkilä M. Fecal calprotectin, lactoferrin, and endoscopic disease activity in monitoring anti-TNF-alpha therapy for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1392-1398. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 175] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | D’Incà R, Dal Pont E, Di Leo V, Benazzato L, Martinato M, Lamboglia F, Oliva L, Sturniolo GC. Can calprotectin predict relapse risk in inflammatory bowel disease? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2007-2014. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 140] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Schoepfer AM, Beglinger C, Straumann A, Safroneeva E, Romero Y, Armstrong D, Schmidt C, Trummler M, Pittet V, Vavricka SR. Fecal calprotectin more accurately reflects endoscopic activity of ulcerative colitis than the Lichtiger Index, C-reactive protein, platelets, hemoglobin, and blood leukocytes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:332-341. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 207] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Costa F, Mumolo MG, Ceccarelli L, Bellini M, Romano MR, Sterpi C, Ricchiuti A, Marchi S, Bottai M. Calprotectin is a stronger predictive marker of relapse in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2005;54:364-368. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 400] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Saverymuttu SH, Hodgson HJ, Chadwick VS, Pepys MB. Differing acute phase responses in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1986;27:809-813. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 97] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Gecse KB, Brandse JF, van Wilpe S, Löwenberg M, Ponsioen C, van den Brink G, D’Haens G. Impact of disease location on fecal calprotectin levels in Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:841-847. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 81] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |