Published online Dec 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.9069

Revised: October 12, 2013

Accepted: October 17, 2013

Published online: December 21, 2013

AIM: To investigate anxiety and depression propensities in patients with toxic liver injury.

METHODS: The subjects were divided into three groups: a healthy control group (Group 1, n = 125), an acute non-toxic liver injury group (Group 2, n = 124), and a group with acute toxic liver injury group caused by non-commercial herbal preparations (Group 3, n = 126). These three groups were compared and evaluated through questionnaire surveys and using the Hospital Anxiety-Depression Scale (HADS), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and the hypochondriasis scale.

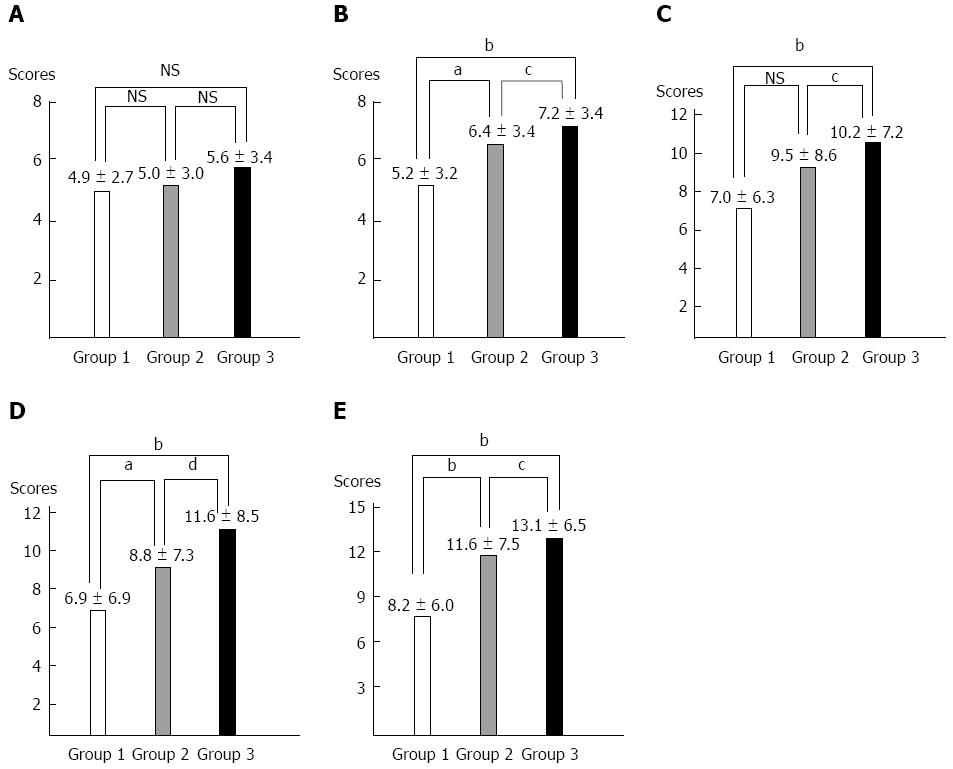

RESULTS: The HADS anxiety subscale was 4.9 ± 2.7, 5.0 ± 3.0 and 5.6 ± 3.4, in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The HADS depression subscale in Group 3 showed the most significant score (5.2 ± 3.2, 6.4 ± 3.4 and 7.2 ± 3.4 in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively) (P < 0.01 vs Group 1, P < 0.05 vs Group 2). The BAI and BDI in Group 3 showed the most significant score (7.0 ± 6.3 and 6.9 ± 6.9, 9.5 ± 8.6 and 8.8 ± 7.3, 10.7 ± 7.2 and 11.6 ± 8.5 in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively) (BAI: P < 0.01 vs Group 1, P < 0.05 vs Group 2) (BDI: P < 0.01 vs Group 1 and 2). Group 3 showed a significantly higher hypochondriasis score (8.2 ± 6.0, 11.6 ± 7.5 and 13.1 ± 6.5 in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively) (P < 0.01 vs Group 1, P < 0.05 vs Group 2).

CONCLUSION: Psychological factors that present vulnerability to the temptation to use alternative medicines, such as herbs and plant preparations, are important for understanding toxic liver injury.

Core tip: In South Korea, the number of toxic liver injuries caused by herbal and folk remedies is increasing. Although positive views on folk remedies are widespread and patients who have been hospitalized with toxic liver injury are often re-hospitalized, no studies have been conducted on the correlation between toxic liver injury and anxiety or depression. This multi-center nation-wide prospective study showed the anxiety and depression propensities in patients with toxic liver injury. Psychological factors that lead to vulnerability to the temptation to use alternative medicines, such as herbs and plant preparations, are important to better understand toxic liver injury.

- Citation: Suh JI, Sakong JK, Lee K, Lee YK, Park JB, Kim DJ, Seo YS, Lee JD, Ko SY, Lee BS, Kim SH, Kim BS, Kim YS, Lee HJ, Kim IH, Sohn JH, Kim TY, Ahn BM. Anxiety and depression propensities in patients with acute toxic liver injury. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(47): 9069-9076

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i47/9069.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.9069

As interest in health is increasing due to the rising average life expectancy, the aging population, and increased income, the use of unconventional medicines processed from various natural substances is increasing[1]. The frequency of the use of unconventional medicines is currently far higher than previously reported. The extents of use and costs of such medicines are also more wide and expensive in the United States[2].

In South Korea, liver injuries caused by the abuse of oriental medicines and folk remedies with no clinical study results are increasing because many people still depend on easily accessible oriental medicines and folk remedies[3]. In particular, the groundless belief that natural extracts and plant preparations have less adverse effects is widespread among the general public, and liver injuries caused by the misuse and abuse of such substances are gradually increasing[4]. A retrospective multi-center preliminary study, which was performed in 7 university hospitals in South Korea across the country in 2003, reported that the estimated annual incidence of hospitalization of patients with toxic hepatitis at a university hospital in South Korea was 2629.8[5]. Four years investigation of patients with acute liver injury in the Gyeongju area, located in southeast South Korea, found that 52% of patients had drug-induced liver injuries, and about 50% of such liver injuries were caused by plant preparations[6]. In a recent prospective nationwide study of drug-induced liver injury in South Korea, the most common cause of drug-induced liver injury was found to be “herbal medications”[7]. Toxic hepatitis is often seen in clinical settings, but the general public has a lower interest in and less knowledge of toxic hepatitis than viral hepatitis. Even though most people in South Korea are exposed to oriental medicines and supplementary health foods made of plant preparations that may induce hepatotoxicity, basic data about the frequency, the clinical catamnesis and the medical and social costs of hepatotoxicity caused by such substances are insufficient. Therefore, active reports on such clinical experiences are needed; however, it is difficult to definitively diagnose most cases of liver injuries that are presumed to be caused by plant preparations; thus, they are kept idle[8-10]. Furthermore, because repetitive exposures to preparations that cause liver injuries have been clinically observed, studies are needed on the psychoneurotic propensities of patients who are exposed to supplementary health foods, oriental medicines, and folk remedies that cause liver injuries.

The symptoms of anxiety and depression are often observed in psychiatry, and they are also often discovered in patients with non-psychiatric physical disease. Considerable research has been conducted regarding anxiety or depression in non-psychiatric general or medical practice[11-14].

As shown by the above-mentioned studies, it is a well-known fact that such medical diseases are accompanied by anxiety and depression symptoms. Even though positive views on folk remedies are widespread and patients who have been hospitalized with toxic liver injury are often re-hospitalized, no studies have been conducted on the correlation between toxic liver injury which is frequently observed in South Korea in patients with anxiety and depression. Thus, this multi-center nation-wide study was intended to investigate the propensities associated with anxiety and depression in patients with toxic liver injury.

This is a prospective, multi-center study using questionnaire surveys to determine the anxiety and depression of patients with toxic liver injury who were selected by their Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) scores, which were determined from their medical records. The RUCAM system is a means of assigning points for clinical, biochemical, serologic and radiologic features of liver injury, which gives an overall assessment score that reflects the likelihood that the hepatic injury is due to a specific medication[15].

The study groups were enrolled between May 1, 2010 and April 30, 2012. Ten university hospitals in South Korea (Konkuk University, Korea University, Catholic University of Daegu, Dongguk University, Soon Chun Hyang University, Yeongnam University, Chonbuk National University, Chungnam National University, Hallym University, and Hanyang University) participated in this study.

The subjects were divided into three groups: a control group, a non-toxic acute liver injury group, and a toxic acute liver injury group involving toxic hepatitis. The subjects were divided as follows; Control group (Group 1): some patients who visited the medical examination center of each hospital for the purpose of medical examination were selected randomly; Non-toxic acute liver injury group (Group 2): patients with acute liver injury due to non-toxic causes such as virus and metabolic causes; and Toxic acute liver injury group (Group 3): patients with acute liver injury caused by toxic causes.

To identify the cause of acute liver injury, careful history taking, physical examination, liver function test, viral hepatitis serological testing (anti-HAV IgM, HBsAg, anti-HBC IgM, anti-HCV antibody, CMV, EBV, HSV), anti-nuclear antibody, anti-mitochondrial antibody, or imaging studies (abdominal sonography or CT) were performed.

These three groups were compared and evaluated through the questionnaire survey using scales of anxiety and depression, and the causative factors were analyzed. Liver injury was defined as cases in which the serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or conjugated bilirubin values were increased more than twice the upper limit of normal, or that aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin were increased together with at least one of them being more than twice the upper limit of normal[16]. The acute nature of liver injury was defined as cases in which the liver injury had been recovered within 3 mo.

Toxic liver injury was defined as an acute liver injury, caused by medicinal herbs, plant preparations, health foods and folk remedies, with the exception of commercial drugs, having a score of 4 or higher on the RUCAM scale. After the purpose of this study was explained to patients with liver injury, only the patients, who agreed to participate in the survey, were selected as subjects. The following patients were excluded from this study: patients whose cases have been diagnosed as or who are receiving treatment by a psychiatrist for depression disorder, dysthymic disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or organic mental disorder, and patients who did not respond to the survey during outpatient visits.

Questionnaires including the following questions were answered by the selected subjects and were collected, and the characteristics of the clinical study groups were compared and analyzed. The questionnaire included general questions on age, sex, etc.; questions from the Hospital Anxiety-Depression Scale (HADS), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and the hypochondriasis scale. The questionnaire surveys were conducted during the hospital visit for Group 1 and at the time of admission for Groups 2 and 3.

After collecting the 448 case questionnaires answered by the subjects, 73 case questionnaires were excluded because the patient failed to answer all of the questions, acute liver injury caused by commercial drugs, chronic liver disease, a RUCAM score of 4 or less, or an AST/ALT value that did not correspond with aute liver injury. The other 375 case questionnaires were analyzed. Accordingly, 125, 124, and 126 subjects were selected for Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

HADS was developed by Zigmond and Snaith in 1983 to identify the caseness (possible and probable) of anxiety disorders and depression among patients in nonpsychiatric hospital clinics[17]. The tool includes 14 items, seven related to anxiety and seven related to depression, each scored between 0 and 3. The authors recommended that a score above 8 on an individual scale should be regarded as a possible case and a score above 10 a probable case[18]. To rule out somatic disorders on the scores, all symptoms of anxiety or depression that were related to a physical disorder, such as dizziness, headaches, insomnia, anergia and fatigue, were excluded.

BAI is a 21 item self-report questionnaire measuring common symptoms of clinical anxiety, such as nervousness and fear of losing control. Respondents indicated the degree to which they are affected by each symptom. Each symptom is scored on a range from 0 to 3, with higher scores corresponding to higher levels of anxiety. Thirteen items assess physiological symptoms, five describe cognitive aspects, and three represent both somatic and cognitive symptoms[19]. A score above 21 is considered a breaking point and was distributed among each of the groups.

BDI is a 21 item self-reported questionnaire that measures the status of clinical depression without psychological diagnosis[20]. It consists of 8 items of physical depression and 13 items of non-physical depression. The BDI covers cognitive, emotional, and somatic symptoms, and its reliability, sensitivity and specificity have a high affinity for diagnosing depression[21,22]. Each item is scored ranging from 0 to 3, with higher scores corresponding to higher levels of depression. A score above 21 is considered a breaking point and was divided evenly among each of the groups.

To measure hypochondriasis, 33 questions corresponding to the hypochondriasis in the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, which is widely used in psychiatry, were extracted, and the total score was used for data analysis.

The SPSS for Windows 19.0 (IBM, New York, NY, United States) statistics program was used for statistical processing of the data. Main results were presented as mean ± SD and the statistical significance was determined by P values smaller than 0.05. For comparison of continuous variables among the patient groups and the control groups or comparison of various variables depending upon different severity levels in the patient groups, nonparametric analyses (Kruskal-Wallis test and subsequent Mann-Whitney U test) were performed. The categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test.

Of the 375 total subjects, Groups 1, 2, and 3 consisted of 125, 124, and 126 subjects, respectively. The average age was 45.2 ± 13.7 in Group 1, 37.7 ± 14.3 in Group 2, and 48.4 ± 13.1 in Group 3. The male-female ratio was 1:1.5 in Group 1, 1:1.5 in Group 2, and 1:1.5 in Group 3. In Group 2, the primary cause of acute liver injury was acute viral hepatitis A (Table 1). In Group 3, with toxic liver injury, the mean RUCAM score was 7.14 ± 1.6 (4-11). As a cause of liver cell injuries by types, hepatocellular liver injuries were found in 96 cases (76.1%), cholestatic in 11 cases (8.7%), and a mixed type in 19 cases (15.0%).

| Demographic data | Group 1 (n = 125) | Group 2 (n = 124) | Group 3 (n = 126) |

| Mean age (yr) (range) | 45.2 ± 13.7 (20-78) | 37.7 ± 14.3 (22-87) | 48.4 ± 13.1 (18-72) |

| M:F (n) | 1:1.5 (50:75) | 1:1.5 (50:74) | 1:1.5 (50:76) |

| Cause (n) | Healthy control (125) | Acute HAV (75) | Toxic hepatitis (126) |

| Unknown (34) | |||

| Acute HBV (5) | |||

| Alcoholic hepatitis (3) | |||

| Gall stone (3) | |||

| NAFLD (1) | |||

| Cholecystitis (1) | |||

| Cholangitis (1) | |||

| Autoimmune hepatitis (1) |

The anxiety subscale of the HADS was 4.9 ± 2.7 (0-14) in Group 1, 5.0 ± 3.0 (0-15) in Group 2, and 5.6 ± 3.4 (0-16) in Group 3. Group 3 showed the highest score, but there was no significant difference in the HADS between groups (Table 2) (Figure 1). When the breaking point was set at 8, subjects, who had a score of 8 or higher and were thus deemed to have a high anxiety propensity, presented 20 cases (16.0%), 23 cases (18.5%) and 32 cases (25.3%) in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Group 3 had the largest number (Table 3).

| Scale | Group 1 (n = 125) | Group 2 (n = 124) | Group 3 (n = 126) | P value |

| Anxiety mean scores of HADS | 4.9 ± 2.7 | 5.0 ± 3.2 | 5.5 ± 3.4 | 0.110 |

| (range) | (0-14) | (0-15) | (0-16) | |

| Depression mean scores of HADS | 5.2 ± 3.1 | 6.4 ± 3.4 | 7.0 ± 3.5 | 0.000 |

| (range) | (0-13) | (0-16) | (0-15) | |

| BAI mean scores | 7.0 ± 6.5 | 9.5 ± 8.5 | 10.2 ± 7.4 | 0.000 |

| (range) | (0-34) | (0-41) | (0-40) | |

| BDI mean scores | 6.8 ± 7.0 | 8.8 ± 7.3 | 11.2 ± 8.6 | 0.000 |

| (range) | (0-38) | (0-33) | (0-37) | |

| Hypochondriasis scores | 8.2 ± 6.4 | 11.6 ± 7.5 | 12.7 ± 6.7 | 0.000 |

| (range) | (0-27) | (0-31) | (0-25) |

| Scale | Group 1 (n = 125) | Group 2 (n = 124) | Group 3 (n = 126) | P value |

| Anxiety subscale of HADS | ||||

| No. of ≥ 8 scores | 20 (16.0) | 23 (18.5) | 32 (25.3) | 0.157 |

| Depression subscale of HADS | ||||

| No. of ≥ 8 scores | 33 (26.4) | 44 (35.4) | 57 (45.2) | 0.008 |

| BAI | ||||

| No. of ≥ 21 scores | 7 (5.6) | 17 (13.7) | 13 (10.3) | 0.098 |

| BDI | ||||

| No. of ≥ 21 scores | 6 (4.8) | 10 (8.0) | 19 (15.0) | 0.017 |

The depression subscale of the HADS was 5.2 ± 3.2 (0-13) in Group 1, 6.4 ± 3.4 (0-16) in Group 2, and 7.2 ± 3.4 (0-15) in Group 3. Group 3 showed the highest score, which was significantly higher than Groups 1 and 2 (P < 0.01 vs Group 1, P < 0.05 vs Group 2) (Table 2) (Figure 1). When the breaking point was set at 8, the number of subjects, who had a score of 8 or higher and were thus deemed to have a high depression propensity, included were 33 cases (26.4%), 44 cases (35.4%) and 57 cases (45.2%) in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Group 3 had the most significant number (P < 0.01) (Table 3).

The mean of the BAI score, which was designed to assess anxiety symptoms, was 7.0 ± 6.3 (0-34) in Group 1, 9.5 ± 8.6 (0-41) in Group 2, and 10.7 ± 7.2 (0-40) in Group 3. Group 3 showed the most statistically significant score (P < 0.01 vs Group 1, P < 0.05 vs Group 2) (Table 2) (Figure 1). When the breaking point was set at 21, subjects, who had a score of 21 or higher and were thus deemed to have a high anxiety propensity, were 7 cases (5.6%), 17 cases (13.7%) and 13 cases (10.3%) in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Group 2 had the largest number, but there was no statistical significance (Table 3).

The mean of the BDI score, which was designed to assess depression symptoms, was 6.9 ± 6.9 (0-38) in Group 1, 8.8 ± 7.3 (0-33) in Group 2, and 11.6 ± 8.5 (0-37) in Group 3. Group 3 showed the most statistically significant score (P < 0.01 vs Groups 1 and 2) (Figure 1 and Table 2). When the breaking point was set at 21, subjects, who had a score of 21 or higher and were thus deemed to have a high depression propensity, were 6 cases (4.8%), 10 cases (8.0%) and 19 cases (15.0%) in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Group 3 had the most statistically significant number (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

The present study demonstrates that patients with toxic liver injury had high anxiety and depression propensities. Many studies have recently been conducted on anxiety and depression symptoms accompanying various medical diseases such as diabetes[23,24], cardiovascular diseases[25,26], and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[27,28]. This study has a high value because this was the first study that evaluated patients with toxic liver injury from the psychiatric aspects of anxiety and depression. Furthermore, as a multi-center study, we are confident that the results of this study represent the nationwide pattern in South Korea.

From the above results, although the HADS levels were similar anxiety and depression tend to be observed slightly more in Group 3 compared to that of Group 2 and more in Group 2 compared to that of Group 1. In HADS, the anxiety subscale is not influenced by the 8 cut off point but the depression scale in Group 3 was significantly higher. In BAI and BDI, Group 3 showed a significantly higher rate of anxiety and depression. When subscale 21 was used as a cutoff point in BAI and BDI, the depression scale was particularly very high in the Group 3 patients. These observations show that both anxiety and depression are related to toxic hepatitis but that depression has a particularly high correlation. When the hypochondriasis scale is considered, Group 3 also displays a higher score. This general trend may be the result of the patients’ tendency, due to anxiety and depression, to seek herbal supplements or alternative medicine when faced with toxic hepatitis.

Patients with toxic liver injury can be largely divided into two types: those whose liver injury was unavoidably caused by hospital prescriptions and those whose liver injury was caused by voluntary administration of sought out medicines. We can presume that patients of the latter type would have psychiatrically higher anxiety and depression than the general public, which is the main subject matter in this study.

When this study was designed, we took into consideration that acute liver injury alone could cause anxiety and depression. Therefore, we divided the acute liver injury group into toxic/non-toxic groups. Generally, toxic or drug-induced liver injury displays similar increases in AST and ALT levels. However, causes of the damage are of a different nature: drug-induced liver injury is usually due to the passive intake of prescribed medication as instructed by physicians, whereas toxic liver injury is due to active self medication. Therefore, patients with drug-induced acute liver injury were excluded in this study, and we have a separate study on drug-induced liver injury and toxic liver injury planned.

Generally, there are risk factors such as genetic, nongenetic host susceptibility and environmental factors for idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury[29]. The risk factors for herbal toxic liver injury are not well known. This study is meaningful in that we found that among the risk factors for the herbal or dietary supplement induced toxic liver injury including sex, age, cumulative dosage and herb-drug interaction[30-33], the psycho-behavioral attitude of patients could also be an important risk factor. The reason that toxic liver injury broke out in a large number of females and people aged 50 or older is not known, but the results of this study suggests interpretationally that psychological factors should contribute greatly to such phenomenon.

It is thought that an effective method for preventing toxic liver injury is to treat patients with special care in collaboration with psychiatric treatment rather than simply telling them not to ingest plant preparations or health foods that could cause toxic liver injury. Although it may not be economic to treat all patients by administering drugs in collaboration with psychiatric treatment, it is thought that it could be a good guide to apply these study results, at least generally, to patients who visit the hospital repetitively due to toxic liver injury. This is because the patients, who had visited the hospitals at least 2 or 3 times repetitively due to the toxic liver injury, had higher anxiety and depression scores (data not shown).

This study has one limitation: most subjects in Group 2 were patients with acute hepatitis A. This was unavoidable because acute hepatitis A has recently broken out in a large number in South Korea[34]. However, no statistical difference was shown between the group with the acute liver injury caused by acute hepatitis A and the group with the acute liver injury caused by a small number of other causes. The reason for including Group 2 in the comparison was to determine whether anxiety and depression propensities were secondarily accompanied due to the acute liver injury, or whether the acute liver injury broke out because people with previously high anxiety and depression propensities had often searched for invigorants to rejuvenate their body.

This study is a cross-sectional study that was designed to try to understand the psychological states, such as anxiety and depression, in patients with toxic liver injury who are taking herbal or folk remedies. The primary purpose of our study was achieved by determining the proportion of psychological conditions, such as anxiety and depression, suffered by patients with toxic liver injury taking herbal or folk remedies. However, there are issues that may be pointed out as a limitation of this cross-section study, such as “Does psychological state induce toxic liver injury?” and “Are changes in psychological state caused by toxic liver injury?” The relation can be demonstrated, but this research design may be limit our understanding of causalities. To overcome some of these limitations, we tried to compare the non-toxic acute liver injury group with the normal group. Through this process, we attempted to distinguish between anxiety and depression induced by hospitalization alone. This study demonstrated that the rate of anxiety and depression in patients with toxic liver injury is significantly higher than that of cases without toxic liver injury, even when taking into account the change in the psychological states due to hospitalization. We believe that this finding is a key result of our research. We plan to promote research to clarify the psychological risk factors such as anxiety and depression by comparing healthy individuals who are taking herbal preparations with toxic hepatitis patients taking herbal preparations through a case-control study.

It is thought that it will be necessary to develop scales specifically applicable to anxiety and depression in patients with toxic liver injury. Even though various conventional scales for anxiety and depression were used in this study, we feel that it is necessary to develop specific scales for anxiety and depression in patients with toxic liver injury.

We believe that meaningful results were derived from this study because psychiatric patients who were previously diagnosed with psychiatric disorders were excluded from this study. It is assumed that the results of this study would have a higher significance if a specific scale for patients with toxic liver injury had been used. .

In conclusion, patients with toxic liver injury showed high scores on the HADS, BAI, BDI, and hypochondriasis scales. It can be postulated from this result that patients with toxic liver injury have high anxiety and depression propensities. This fact suggests that high anxiety and depression propensities could be the psychological factors that lead patients with toxic liver injury to access factors that may cause toxic liver injury, such as folk remedies and oriental medicines. It is therefore thought that although it is important to treat toxic liver injury itself, it is necessary to take active measures to understand and improve anxiety and depression symptoms of patients in an effort to prevent toxic liver injury from occurring and recurring.

Even though positive views on herbal preparations or folk remedies are widespread and patients who have been hospitalized with toxic liver injury are often re-hospitalized, no studies have been conducted on the correlation between toxic liver injury which is frequently observed in South Korea and anxiety and depression in patients with toxic liver injury.

Patients with toxic liver injury can be largely divided into two types: those whose liver injury was unavoidably caused by hospital prescriptions and those whose liver injury was caused by voluntary administration of sought out medicines. It can be presumed that patients of the latter type would have psychiatrically higher anxiety and depression than the general public, which is the main subject matter in this study.

This study has a high value because this was the first study that evaluated patients with toxic liver injury from the psychiatric aspects of anxiety and depression. This study indicates that patients with toxic liver injury showed high scores on the Hospital Anxiety-Depression Scale, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Beck Depression Inventory, and the hypochondriasis scales. It can be postulated from this result that patients with toxic liver injury have high anxiety and depression propensities. This fact suggests that high anxiety and depression propensities could be the psychological factors that lead patients with toxic liver injury to access factors that may cause toxic liver injury, such as folk remedies and oriental medicines.

This study indicates that although it is important to treat toxic liver injury itself, it is necessary to take active measures to understand and improve anxiety and depression symptoms of patients in an effort to prevent toxic liver injury from occurring and recurring.

The authors present patients with herbal preparations-induced acute toxic liver injury had high anxiety and depression propensities. The results are interesting and indicate that psychological factors vulnerable to the temptation to use alternative medicines, such as herbs and plant preparations, are most important for understanding the toxic liver injury.

P- Reviewers: Biecker E, Jablonska B, Larentzakis A, Maher MM, Panduro A, Tasci I S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Kessler RC, Davis RB, Foster DF, Van Rompay MI, Walters EE, Wilkey SA, Kaptchuk TJ, Eisenberg DM. Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:262-268. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 496] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 519] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246-252. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2906] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2427] [Article Influence: 78.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ahn BM. [Herbal preparation-induced liver injury]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2004;44:113-125. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Kim JB, Sohn JH, Lee HL, Kim JP, Han DS, Hahm JS, Lee DH, Kee CS. [Clinical characteristics of acute toxic liver injury]. Korean J Hepatol. 2004;10:125-134. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Kim DJ, An BM, Choe SK, Son JH, Seo JI, Park SH, Nam SU, Lee JY, Kim JB, O SM. Preliminary multicenter studies on toxic liver injury. Korean J Hepatol. 2004;10 Suppl 1:80-86. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Chun WJ, Yoon BG, Kim NI, Lee G, Yang CH, Lee CW, Suh JI. A clinical study of patients with acute liver injury caused by herbal medication in Gyeongju area. Korean J Med. 2002;63:141-150. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Suk KT, Kim DJ, Kim CH, Park SH, Yoon JH, Kim YS, Baik GH, Kim JB, Kweon YO, Kim BI. A prospective nationwide study of drug-induced liver injury in Korea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1380-1387. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 146] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Son HS, Kim GS, Lee SW, Kang SB, Back JT, Nam SW, Lee DS, Ahn BM. [Toxic hepatitis associated with carp juice ingestion]. Korean J Hepatol. 2006;12:103-106. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Jung KA, Min HJ, Yoo SS, Kim HJ, Choi SN, Ha CY, Kim HJ, Kim TH, Jung WT, Lee OJ. Drug-Induced Liver Injury: Twenty Five Cases of Acute Hepatitis Following Ingestion of Polygonum multiflorum Thunb. Gut Liver. 2011;5:493-499. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 115] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kang SH, Kim JI, Jeong KH, Ko KH, Ko PG, Hwang SW, Kim EM, Kim SH, Lee HY, Lee BS. [Clinical characteristics of 159 cases of acute toxic hepatitis]. Korean J Hepatol. 2008;14:483-492. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schwab JJ, Bialow M, Brown JM, Holzer CE. Diagnosing depression in medical inpatients. Ann Intern Med. 1967;67:695-707. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Clarke DM, Smith GC. Consultation-liaison psychiatry in general medical units. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1995;29:424-432. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Olfson M, Fireman B, Weissman MM, Leon AC, Sheehan DV, Kathol RG, Hoven C, Farber L. Mental disorders and disability among patients in a primary care group practice. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1734-1740. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Kroenke K, Jackson JL, Chamberlin J. Depressive and anxiety disorders in patients presenting with physical complaints: clinical predictors and outcome. Am J Med. 1997;103:339-347. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 197] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs-I. A novel method based on the conclusions of international consensus meetings: application to drug-induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1323-1330. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Bénichou C. Criteria of drug-induced liver disorders. Report of an international consensus meeting. J Hepatol. 1990;11:272-276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 780] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 737] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28548] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29367] [Article Influence: 716.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Choi-Kwon S, Kim HS, Kwon SU, Kim JS. Factors affecting the burden on caregivers of stroke survivors in South Korea. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1043-1048. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893-897. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7560] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7648] [Article Influence: 218.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Beck AT, Steer RA, Brawn G. Psychometric properties of Beck Depression Inventory: twenty five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77-100. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7481] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7508] [Article Influence: 208.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ambrosini PJ, Metz C, Bianchi MD, Rabinovich H, Undie A. Concurrent validity and psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory in outpatient adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30:51-57. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Johnson DA, Heather BB. The sensitivity of the Beck depression inventory to changes of symptomatology. Br J Psychiatry. 1974;125:184-185. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ludman EJ, Katon W, Russo J, Von Korff M, Simon G, Ciechanowski P, Lin E, Bush T, Walker E, Young B. Depression and diabetes symptom burden. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:430-436. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 171] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Paschalides C, Wearden AJ, Dunkerley R, Bundy C, Davies R, Dickens CM. The associations of anxiety, depression and personal illness representations with glycaemic control and health-related quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:557-564. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 119] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rothenbacher D, Hahmann H, Wüsten B, Koenig W, Brenner H. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with stable coronary heart disease: prognostic value and consideration of pathogenetic links. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14:547-554. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sullivan MD, LaCroix AZ, Baum C, Grothaus LC, Katon WJ. Functional status in coronary artery disease: a one-year prospective study of the role of anxiety and depression. Am J Med. 1997;103:348-356. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 108] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hill K, Geist R, Goldstein RS, Lacasse Y. Anxiety and depression in end-stage COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:667-677. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 131] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Di Marco F, Verga M, Reggente M, Maria Casanova F, Santus P, Blasi F, Allegra L, Centanni S. Anxiety and depression in COPD patients: The roles of gender and disease severity. Respir Med. 2006;100:1767-1774. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 297] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chalasani N, Björnsson E. Risk factors for idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2246-2259. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 227] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Efferth T, Kaina B. Toxicities by herbal medicines with emphasis to traditional Chinese medicine. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12:989-996. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 89] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Seeff LB. Herbal hepatotoxicity. Clin Liver Dis. 2007;11:577-596, vii. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 102] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Seeff LB, Lindsay KL, Bacon BR, Kresina TF, Hoofnagle JH. Complementary and alternative medicine in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;34:595-603. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 187] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fugh-Berman A. Herb-drug interactions. Lancet. 2000;355:134-138. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 790] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 809] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kim YJ, Lee HS. Increasing incidence of hepatitis A in Korean adults. Intervirology. 2010;53:10-14. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |