Published online Oct 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i37.6299

Revised: August 7, 2013

Accepted: August 17, 2013

Published online: October 7, 2013

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a very rare B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder was with an aggressive clinical behavior that recently characterized by the World Health Organization. Although PBL is most commonly observed in the oral cavity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients, it can also be observed at extra-oral sites in HIV-negative patients. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may be closely related the pathogenesis of PBL. PBL shows different clinicopathological characteristics between HIV-positive and -negative patients. Here, we report a case of PBL of the liver in a 79-year-old HIV-negative male. The patient died approximately 1.5 mo after examination and autopsy showed that the main lesion was a very large liver mass. Histopathological examination of the excised lesion showed large-cell lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation diffusely infiltrating the liver and involving the surrounding organs. The neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for CD30, EBV, Bob-1, and CD38. The autopsy findings suggested a diagnosis of PBL. To our knowledge, the present case appears to be the first report of PBL with initial presentation of the liver in a patient without HIV infection.

Core tip: Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a rare B-cell lymphoma. Although PBL is observed in the oral cavity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients, it can also be observed at extra-oral sites in HIV-negative patients. We present a case of PBL of the liver in a 79-year-old HIV-negative male. Histopathological examination showed large-cell lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation diffusely infiltrating the liver and involving the surrounding organs. The neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for CD30, Epstein-Barr virus, Bob-1, and CD38. The present case appears to be the first report of PBL with initial presentation in the liver in a patient without HIV infection.

- Citation: Tani J, Miyoshi H, Nomura T, Yoneyama H, Kobara H, Mori H, Morishita A, Himoto T, Masaki T. A case of plasmablastic lymphoma of the liver without human immunodeficiency virus infection. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(37): 6299-6303

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i37/6299.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i37.6299

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a distinct, aggressive B-cell neoplasm that shows a diffuse proliferation of large neoplastic cells resembling B-immunoblasts with an immunophenotype of plasma cells. PBL was initially described in 1997 as a rare subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and has an aggressive clinical behavior arising in the oral cavity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals[1]. There have been several reports of PBL in HIV-negative patients, mainly at extra-oral sites including the stomach, small intestine and colon[2-6] but not in the liver. Interestingly, most cases of PBL occur without HIV infection in Japan and Korea, where the prevalence of HIV infection is low in comparison to Western countries[7,8]. In the present study, we describe the first case of liver PBL in a 79-year-old HIV-negative Japanese patient.

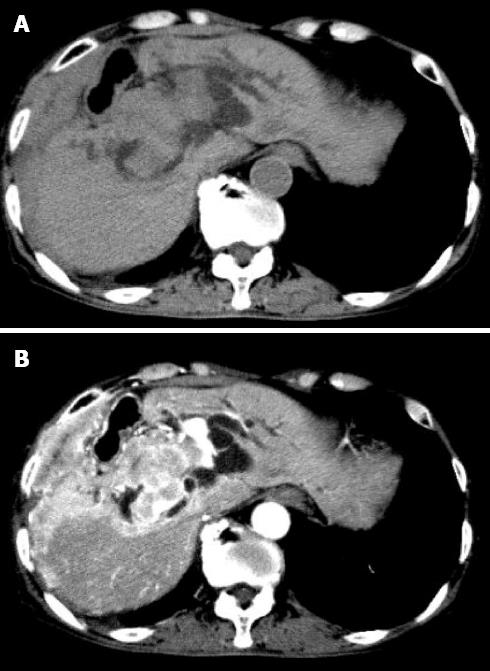

A 79-year-old Japanese man was admitted to our hospital with the chief complaint of abdominal pain and icterus. Upon physical examination, jaundice was found to be prominent, which gradually worsened without relief of symptoms. Abdominal examination revealed the liver was palpable about 10 cm below the costal margin. The transaminase, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin levels all notably exceeded normal values. An abdominal ultrasound showed dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts and a heterogeneous large mass that was 15 cm in diameter located in the right hepatic lobe. Radiographs and computed tomography (CT) of the chest, oral, and peri-oral sites showed no abnormalities, and no peripheral lymphadenopathy was observed. Serological tests to detect specific antibodies against hepatitis B and C virus were negative. The carcinoembryonic antigen and alpha-fetoprotein levels were normal, but soluble interleukin-2 receptor was high (5760 U/mL), and the patient tested negative for an anti-HIV antibody. The examination of the serum levels of Bence-Jones protein and rheumatoid factor was also negative. The patient’s medical history included a gastrectomy for a gastric ulcer 20 years earlier and a hepatectomy for a liver abscess 5 years earlier. Plain (Figure 1A) and enhanced (Figure 1B) abdominal CT revealed a liver tumor and hepatomegaly with the same lesion present on ultrasonography (US).

Following examination, a US percutaneous-guided fine needle liver biopsy was performed. Histopathological examination of the biopsy smears showed a dense infiltrate composed of diffuse and proliferative large immunoblast cells with a typical morphological appearance of high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. However, we were unable to make a diagnosis due to poor immunostaining and a low number of specimens. During the detailed examination, CT and US revealed tumor progression with jaundice, despite continued percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.

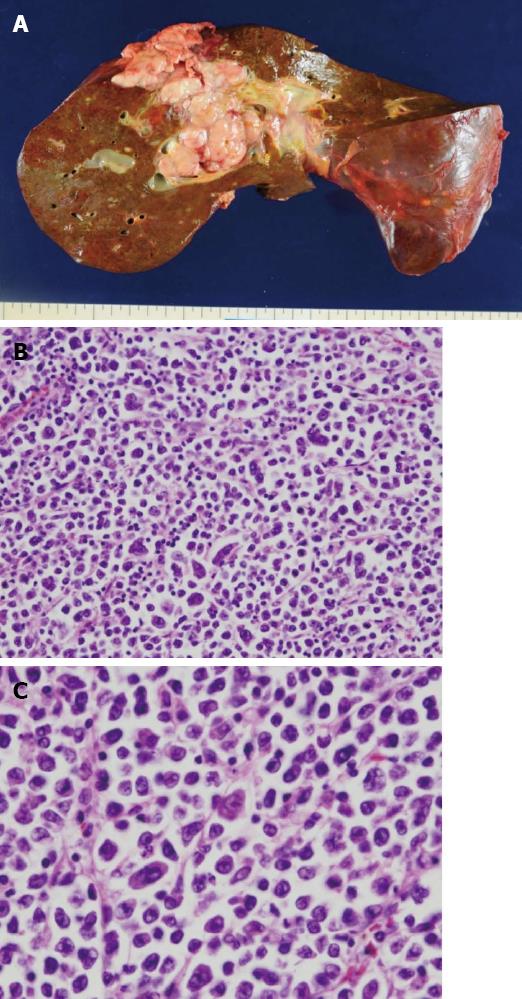

Considering the high tumor burden and poor prognosis, the patient chose not to receive chemotherapy. He received palliative care and passed away due to multiple organ failure 1.5 mo after his initial clinical presentation. An autopsy was performed immediately after his death. Gross findings included a white, soft solid tumor of approximately diameter of 10 cm in the liver that involved the diaphragm and parietal peritoneum (Figure 2A). Histologically, large tumor cells with abundant basophilic cytoplasm were diffusely proliferative, and large nuclei were sporadically or centrally located and contained one or two conspicuous nucleoli in the central portion (Figure 2B). Specifically, the tumor cells had plasmablast- or immunoblast-like morphology, and there were almost no mature plasma cells present (Figure 2C). Additionally, binucleated or multinucleated tumor cells were scattered throughout the specimen, tumor cell proliferation in lymphatic vessels was conspicuous, and tumor cell invasion was found in some blood vessels.

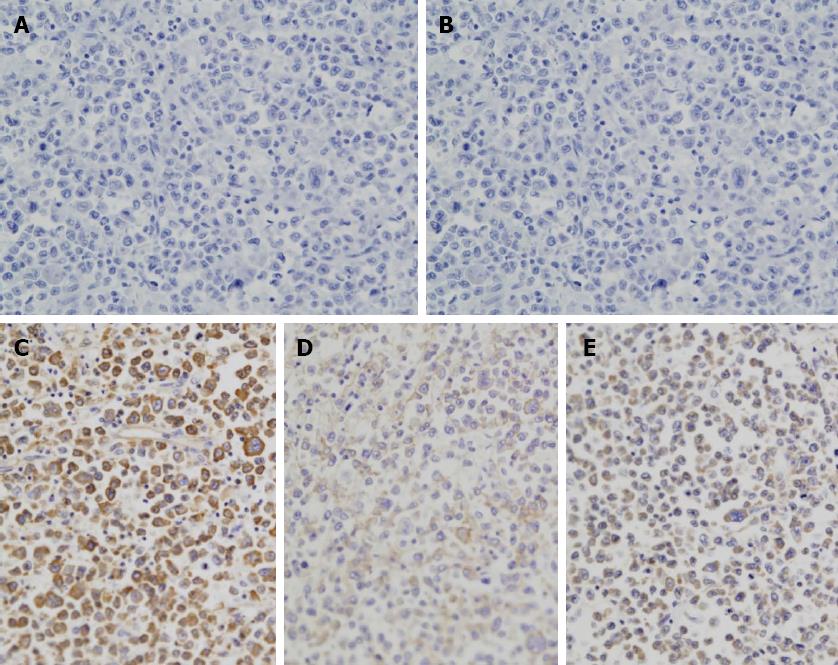

Immunohistochemical examination revealed that the tumor cells were negative for B-cell markers CD20 (Figure 3A) and CD3 (Figure 3B) but positive for CD30 (Figure 3C), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (Figure 3D), and Bob-1 (Figure 3E). Although over 90% of the tumor cells were positive for Ki-67, they were negative for epithelial cell markers such as AEI/AE3, S100 protein, CD43, CD56, PAX-5, and human herpes virus (HHV)-8. Almost all tumor cells were highly positive for EBV virus-encoded RNA in situ hybridization (EBER-ISH). Based on these results, a diagnosis of PBL was made.

DLBCL is currently considered to be a heterogeneous group of rare tumors primarily occurring in the presence of HIV infection[9,10]. DLBCL with plasmablastic features has recently been categorized into the following subtypes: PBL of the oral cavity, PBL with plasmacytic differentiation, classic primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), extracavitary/solid PEL or HHV8-associated DLBCL, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive DLBCL[10,11].

PBL is a rare lymphoma accounting for approximately 2.6% of AIDS-related neoplasms[12] and typically occurs in the oral cavity of HIV-infected patients. Recently, however, PBL has been reported in patients without HIV infection, and several cases have been reported in extra-oral locations, such as skin, subcutaneous tissue, stomach, anal mucosa, lung, and lymph node regions[3-6,13,14]. PBL has also been observed in immunocompromised individuals such as organ transplant patients and the elderly. PBL with HIV infection primarily affects men at a young age, while the clinical characteristics of PBL without HIV infection are typically old age with a slight male predominance[15]. This difference reflects the epidemiology of HIV infection. In addition, over one-third of all cases with PBL were first noted at extra-oral locations[16]. Interestingly, although the gastrointestinal tract has been observed to be the most common extraoral site (10.6%), the liver is a rare extra-oral location in PBL patients[16]. Only one case of liver PBL patient with HIV infection has been reported[17].

PBL is a distinct, aggressive B-cell neoplasm that shows a diffuse proliferation of large neoplastic cells resembling B-immunoblasts with an immunophenotype of plasma cells. PBL cells predominantly exhibit the morphological features of plasmablasts/immunoblasts and are immunohistologically negative or slightly positive for B-cell markers such as CD20 and CD79a but positive for plasmacyte markers such as CD38 and CD138. PBL cells are highly reactive to the cell proliferation marker Ki67, and 2 in 3 patients carry an integrated EBV genome, while HHV8 is negative. EBER-ISH is highly positive in PBL cells; in particular, EBER-ISH has a positive predictive value of close to 100% in HIV-positive PBL patients with presentation in the oral cavity[18,19].

Differential diagnosis is needed for poorly differentiated carcinomas and malignant melanomas, in addition to malignant lymphomas, such as anaplastic (plasmablastic) plasmacytoma (AP), Burkitt’s lymphoma, and DLBCL-NOS[20]. Although a differential diagnosis of AP is especially difficult because of tumor cell morphology and immunohistochemical results that are similar to other subtypes, AP cases are usually preceded by a plasmacytoma such as multiple myeloma.

Because the positive value of EBER is significantly high in PBL patients, it has been suggested to use this value as a diagnostic tool[18]. However, some plasmacytomas with no signs of immune system abnormalities exhibit plasmablast-like morphology with a particularly high EBER-positive rate[21]. To differentiate the two diseases, it is important to use clinical findings (such as the presence of multiple myeloma and M protein) in addition to histopathological and immunohistological findings. The overall prognosis of PBL is poor [12,15]; however, the prognosis of PBL in HIV-positive patients has improved with the enhanced management of HIV symptoms, but it has worsened in HIV-negative patients, which include a large elderly population[7,15]. MYC/IgH translocation is observed in 70% of EBER-positive PBL patients, and, interestingly, these patients have a notably worse PBL prognosis, presenting with an endemic Burkitt lymphoma-like phenotype and symptoms[22,23].

The management of PBL is based mainly on early aggressive chemotherapy. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) and CHOP-like regimens are commonly used with a good overall response rate but have a high relapse rate and poor overall survival[24].

In our case, no primary carcinoma was detected in any organs at autopsy. In cases of malignant melanoma, tumor cells are immunohistochemically positive for melanosomes and S-100 protein, and Burkitt’s lymphomas expresses LCA, CD20, and CD79a. A differential diagnosis between PBL and plasmacytoma is often difficult without histological examination. Because PBL is composed almost entirely of blast cells, plasmacytoma typically consists of mature plasma cells. Therefore, the morphology and immunophenotype of both tumor cells, as well as clinical features, are essential for an accurate diagnosis of PBL.

The condition of the patient rapidly deteriorated because we failed to provide proper treatment due to the unsuccessful initial histopathological examination of the liver biopsy. If biopsy specimens show similar pathological features to those presented in this study, a differential diagnosis of PBL and an immunohistochemical analysis of CD138 and EBER are urgently needed. Although there is one reported case of PBL originating in the liver[17], to our knowledge, this is the first case report of PBL that occurred in the liver without HIV infection. Because extra-oral PBL can occur in HIV-negative patients and has a poor prognosis, it should be included as a differential diagnosis in cases of suspected hepatic lymphoma.

P- Reviewer Cha JM S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Ma S

| 1. | Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, Hummel M, Marafioti T, Schneider U, Huhn D, Schmidt-Westhausen A, Reichart PA, Gross U. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89:1413-1420. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Masgala A, Christopoulos C, Giannakou N, Boukis H, Papadaki T, Anevlavis E. Plasmablastic lymphoma of visceral cranium, cervix and thorax in an HIV-negative woman. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:615-618. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chabay P, De Matteo E, Lorenzetti M, Gutierrez M, Narbaitz M, Aversa L, Preciado MV. Vulvar plasmablastic lymphoma in a HIV-positive child: a novel extraoral localisation. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:644-646. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hatanaka K, Nakamura N, Kishimoto K, Sugino K, Uekusa T. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the cecum: report of a case with cytologic findings. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:297-300. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu JJ, Zhang L, Ayala E, Field T, Ochoa-Bayona JL, Perez L, Bello CM, Chervenick PA, Bruno S, Cultrera JL. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative plasmablastic lymphoma: a single institutional experience and literature review. Leuk Res. 2011;35:1571-1577. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tavora F, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Sun CC, Burke A, Zhao XF. Extra-oral plasmablastic lymphoma: report of a case and review of literature. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1233-1236. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Teruya-Feldstein J, Chiao E, Filippa DA, Lin O, Comenzo R, Coleman M, Portlock C, Noy A. CD20-negative large-cell lymphoma with plasmablastic features: a clinically heterogenous spectrum in both HIV-positive and -negative patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1673-1679. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 147] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yotsumoto M, Ichikawa N, Ueno M, Higuchi Y, Asano N, Kobayashi H. CD20-negative CD138-positive leukemic large cell lymphoma with plasmablastic differentiation with an IgH/MYC translocation in an HIV-positive patient. Intern Med. 2009;48:559-562. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | De Paepe P, De Wolf-Peeters C. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas comprising several distinct clinicopathological entities. Leukemia. 2007;21:37-43. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 89] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Carbone A, Gloghini A. AIDS-related lymphomas: from pathogenesis to pathology. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:662-670. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 161] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Teruya-Feldstein J. Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with plasmablastic differentiation. Curr Oncol Rep. 2005;7:357-363. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Carbone A, Gloghini A. Plasmablastic lymphoma: one or more entities? Am J Hematol. 2008;83:763-764. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Takahashi Y, Saiga I, Fukushima J, Seki N, Sugimoto N, Hori A, Eguchi K, Fukusato T. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the retroperitoneum in an HIV-negative patient. Pathol Int. 2009;59:868-873. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chuah KL, Ng SB, Poon L, Yap WM. Plasmablastic lymphoma affecting the lung and bone marrow with CD10 expression and t(8; 14)(q24; q32) translocation. Int J Surg Pathol. 2009;17:163-166. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Stachurski D, Perez K, Jabbour M, Milani C, Colvin GA, Butera JN. HIV-negative plasmablastic lymphoma: not in the mouth. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11:185-189. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Riedel DJ, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Zhao XF, Redfield RR, Gilliam BL. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity: a rapidly progressive lymphoma associated with HIV infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:261-267. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Metta H, Corti M, Maranzana A, Schtirbu R, Narbaitz M, De Dios Soler M. Unusual case of plasmablastic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma located in the liver. First case reported in an AIDS patient. Ann Hepatol. 2009;8:242-245. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Vega F, Chang CC, Medeiros LJ, Udden MM, Cho-Vega JH, Lau CC, Finch CJ, Vilchez RA, McGregor D, Jorgensen JL. Plasmablastic lymphomas and plasmablastic plasma cell myelomas have nearly identical immunophenotypic profiles. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:806-815. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 240] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dong HY, Scadden DT, de Leval L, Tang Z, Isaacson PG, Harris NL. Plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV-positive patients: an aggressive Epstein-Barr virus-associated extramedullary plasmacytic neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1633-1641. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Colomo L, Loong F, Rives S, Pittaluga S, Martínez A, López-Guillermo A, Ojanguren J, Romagosa V, Jaffe ES, Campo E. Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with plasmablastic differentiation represent a heterogeneous group of disease entities. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:736-747. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Chang ST, Liao YL, Lu CL, Chuang SS, Li CY. Plasmablastic cytomorphologic features in plasma cell neoplasms in immunocompetent patients are significantly associated with EBV. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:339-344. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Valera A, Balagué O, Colomo L, Martínez A, Delabie J, Taddesse-Heath L, Jaffe ES, Campo E. IG/MYC rearrangements are the main cytogenetic alteration in plasmablastic lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1686-1694. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 191] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bogusz AM, Seegmiller AC, Garcia R, Shang P, Ashfaq R, Chen W. Plasmablastic lymphomas with MYC/IgH rearrangement: report of three cases and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:597-605. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Stachurski D, Perez K, Jabbour M, Milani C, Colvin G, Butera JN. Prognostic factors in chemotherapy-treated patients with HIV-associated Plasmablastic lymphoma. Oncologist. 2010;15:293-299. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |